Animal colouration on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Animal coloration is the general appearance of an animal resulting from the reflection or emission of

Animal coloration has been a topic of interest and

Animal coloration has been a topic of interest and

Abstract

Full text

.

Abbott Handerson Thayer's 1909 book '' Concealing-Coloration in the Animal Kingdom'', completed by his son Gerald H. Thayer, argued correctly for the widespread use of

Abbott Handerson Thayer's 1909 book '' Concealing-Coloration in the Animal Kingdom'', completed by his son Gerald H. Thayer, argued correctly for the widespread use of

Protective resemblance is used by prey to avoid predation. It includes special protective resemblance, now called

Protective resemblance is used by prey to avoid predation. It includes special protective resemblance, now called  Aggressive resemblance is used by

Aggressive resemblance is used by

Advertising coloration can signal the services an animal offers to other animals. These may be of the same species, as in

Advertising coloration can signal the services an animal offers to other animals. These may be of the same species, as in

Darwin observed that the males of some species, such as birds-of-paradise, were very different from the females.

Darwin explained such male-female differences in his theory of sexual selection in his book ''

Darwin observed that the males of some species, such as birds-of-paradise, were very different from the females.

Darwin explained such male-female differences in his theory of sexual selection in his book ''

Warning coloration (aposematism) is effectively the "opposite" of camouflage, and a special case of advertising. Its function is to make the animal, for example a wasp or a coral snake, highly conspicuous to potential predators, so that it is noticed, remembered, and then avoided. As Peter Forbes observes, "Human warning signs employ the same colours – red, yellow, black, and white – that nature uses to advertise dangerous creatures."Forbes, 2009. p. 52 and plate 24. Warning colours work by being associated by potential predators with something that makes the warning coloured animal unpleasant or dangerous. This can be achieved in several ways, by being any combination of:

Warning coloration (aposematism) is effectively the "opposite" of camouflage, and a special case of advertising. Its function is to make the animal, for example a wasp or a coral snake, highly conspicuous to potential predators, so that it is noticed, remembered, and then avoided. As Peter Forbes observes, "Human warning signs employ the same colours – red, yellow, black, and white – that nature uses to advertise dangerous creatures."Forbes, 2009. p. 52 and plate 24. Warning colours work by being associated by potential predators with something that makes the warning coloured animal unpleasant or dangerous. This can be achieved in several ways, by being any combination of:

* distasteful, for example caterpillars, pupae and adults of the cinnabar moth, the

* distasteful, for example caterpillars, pupae and adults of the cinnabar moth, the

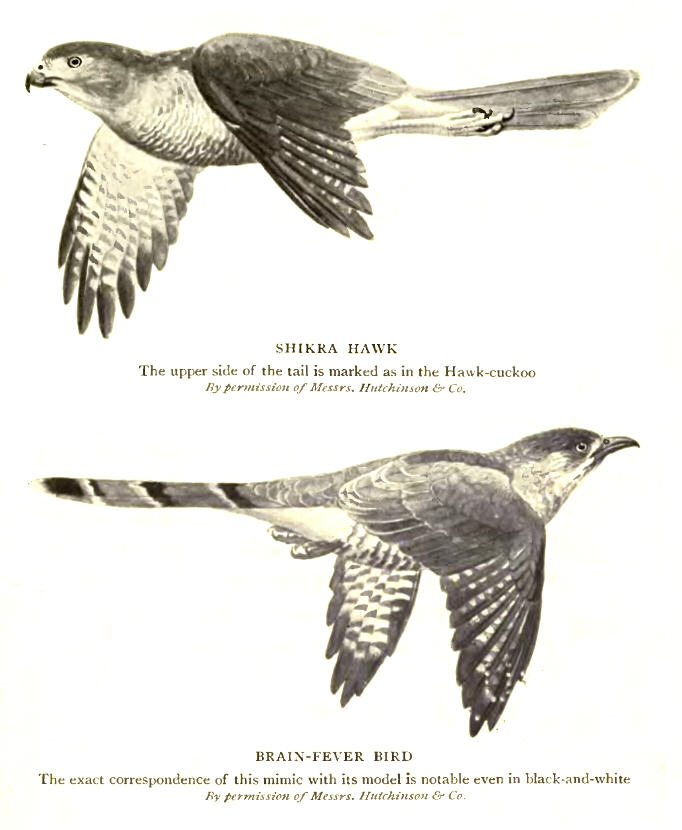

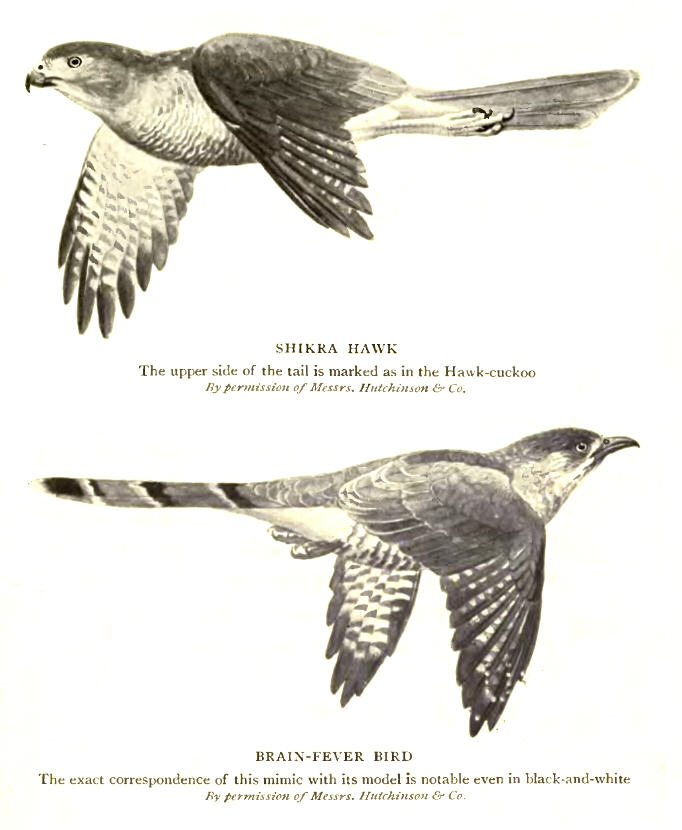

Mimicry means that one species of animal resembles another species closely enough to deceive predators. To evolve, the mimicked species must have warning coloration, because appearing to be bitter-tasting or dangerous gives

Mimicry means that one species of animal resembles another species closely enough to deceive predators. To evolve, the mimicked species must have warning coloration, because appearing to be bitter-tasting or dangerous gives

Some frogs such as '' Bokermannohyla alvarengai'', which basks in sunlight, lighten their skin colour when hot (and darkens when cold), making their skin reflect more heat and so avoid overheating.

Some frogs such as '' Bokermannohyla alvarengai'', which basks in sunlight, lighten their skin colour when hot (and darkens when cold), making their skin reflect more heat and so avoid overheating.

Some animals are coloured purely incidentally because their blood contains pigments. For example, amphibians like the

Some animals are coloured purely incidentally because their blood contains pigments. For example, amphibians like the

Animal coloration may be the result of any combination of

Animal coloration may be the result of any combination of

Pigments are coloured chemicals (such as

Pigments are coloured chemicals (such as

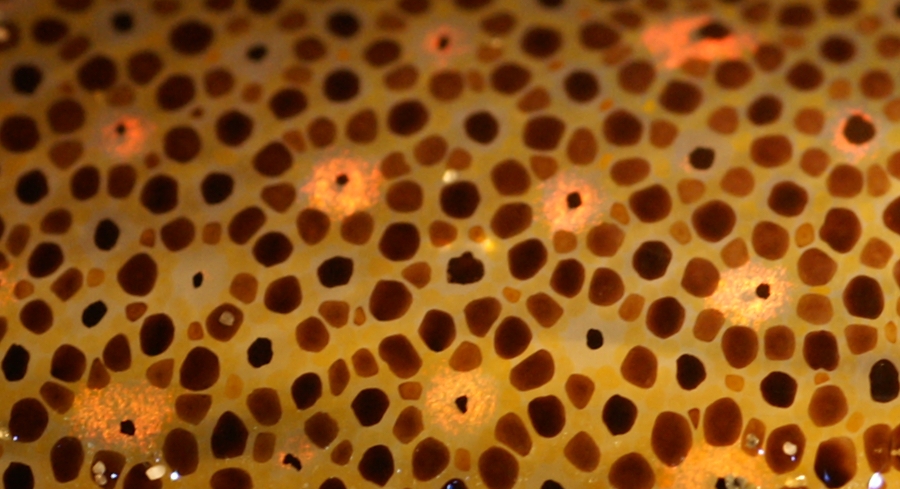

Chromatophores are special pigment-containing cells that may change their size, but more often retain their original size but allow the pigment within them to become redistributed, thus varying the colour and pattern of the animal. Chromatophores may respond to hormonal and/or neurobal control mechanisms, but direst responses to stimulation by visible light, UV-radiation, temperature, pH-changes, chemicals, etc. have also been documented. The voluntary control of chromatophores is known as metachrosis. For example,

Chromatophores are special pigment-containing cells that may change their size, but more often retain their original size but allow the pigment within them to become redistributed, thus varying the colour and pattern of the animal. Chromatophores may respond to hormonal and/or neurobal control mechanisms, but direst responses to stimulation by visible light, UV-radiation, temperature, pH-changes, chemicals, etc. have also been documented. The voluntary control of chromatophores is known as metachrosis. For example,

While many animals are unable to synthesize carotenoid pigments to create red and yellow surfaces, the green and blue colours of bird feathers and insect carapaces are usually not produced by pigments at all, but by structural coloration. Structural coloration means the production of colour by microscopically-structured surfaces fine enough to interfere with

While many animals are unable to synthesize carotenoid pigments to create red and yellow surfaces, the green and blue colours of bird feathers and insect carapaces are usually not produced by pigments at all, but by structural coloration. Structural coloration means the production of colour by microscopically-structured surfaces fine enough to interfere with

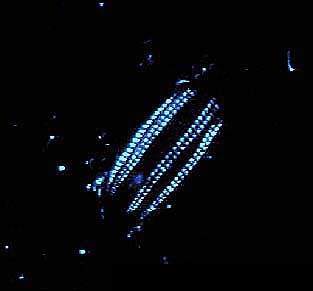

Bioluminescence is the production of

Bioluminescence is the production of

Theme issue 'Animal coloration: production, perception, function and application'

(Royal Society)

* ttp://www.bioscience-explained.org/ENvol1_2/pdf/paletteEN.pdf Nature's Palette: How animals, including humans, produce colours {{Navboxes , title=Articles related to Animal coloration , list = {{vision in animals, state=expanded {{modelling ecosystems, expanded=none {{colour topics Zoology Evolution of animals Mimicry Warning coloration Camouflage

light

Light, visible light, or visible radiation is electromagnetic radiation that can be visual perception, perceived by the human eye. Visible light spans the visible spectrum and is usually defined as having wavelengths in the range of 400– ...

from its surfaces. Some animals are brightly coloured, while others are hard to see. In some species, such as the peafowl

Peafowl is a common name for two bird species of the genus '' Pavo'' and one species of the closely related genus '' Afropavo'' within the tribe Pavonini of the family Phasianidae (the pheasants and their allies). Male peafowl are referred t ...

, the male has strong patterns, conspicuous colours and is iridescent

Iridescence (also known as goniochromism) is the phenomenon of certain surfaces that appear gradually to change colour as the angle of view or the angle of illumination changes. Iridescence is caused by wave interference of light in microstruc ...

, while the female is far less visible.

There are several separate reasons why animals have evolved colours. Camouflage

Camouflage is the use of any combination of materials, coloration, or illumination for concealment, either by making animals or objects hard to see, or by disguising them as something else. Examples include the leopard's spotted coat, the b ...

enables an animal to remain hidden from view. Animals use colour to advertise

Advertising is the practice and techniques employed to bring attention to a product or service. Advertising aims to present a product or service in terms of utility, advantages, and qualities of interest to consumers. It is typically use ...

services such as cleaning

Cleaning is the process of removing unwanted substances, such as dirt, infectious agents, and other impurities, from an object or environment. Cleaning is often performed for beauty, aesthetic, hygiene, hygienic, Function (engineering), function ...

to animals of other species; to signal

A signal is both the process and the result of transmission of data over some media accomplished by embedding some variation. Signals are important in multiple subject fields including signal processing, information theory and biology.

In ...

their sexual status to other members of the same species; and in mimicry

In evolutionary biology, mimicry is an evolved resemblance between an organism and another object, often an organism of another species. Mimicry may evolve between different species, or between individuals of the same species. In the simples ...

, taking advantage of the warning coloration

Aposematism is the Advertising in biology, advertising by an animal, whether terrestrial or marine, to potential predation, predators that it is not worth attacking or eating. This unprofitability may consist of any defenses which make the pr ...

of another species. Some animals use flashes of colour to divert attacks by startling predators. Zebras may possibly use motion dazzle, confusing a predator's attack by moving a bold pattern rapidly. Some animals are coloured for physical protection, with pigments in the skin to protect against sunburn, while some frogs can lighten or darken their skin for temperature regulation

Thermoregulation is the ability of an organism to keep its body temperature within certain boundaries, even when the surrounding temperature is very different. A thermoconforming organism, by contrast, simply adopts the surrounding temperature ...

. Finally, animals can be coloured incidentally. For example, blood is red because the haem pigment needed to carry oxygen is red. Animals coloured in these ways can have striking natural patterns

Patterns in nature are visible regularities of form found in the nature, natural world. These patterns recur in different contexts and can sometimes be modelled mathematically. Natural patterns include symmetries, trees, spirals, meanders, wav ...

.

Animals produce colour in both direct and indirect ways. Direct production occurs through the presence of visible coloured cells known as pigment

A pigment is a powder used to add or alter color or change visual appearance. Pigments are completely or nearly solubility, insoluble and reactivity (chemistry), chemically unreactive in water or another medium; in contrast, dyes are colored sub ...

which are particles of coloured material such as freckles. Indirect production occurs by virtue of cells known as chromatophore

Chromatophores are cells that produce color, of which many types are pigment-containing cells, or groups of cells, found in a wide range of animals including amphibians, fish, reptiles, crustaceans and cephalopod

A cephalopod is any member o ...

s which are pigment-containing cells such as hair follicles. The distribution of the pigment particles in the chromatophores can change under hormonal

A hormone (from the Greek participle , "setting in motion") is a class of signaling molecules in multicellular organisms that are sent to distant organs or tissues by complex biological processes to regulate physiology and behavior. Hormones a ...

or neuronal

A neuron (American English), neurone (British English), or nerve cell, is an excitable cell that fires electric signals called action potentials across a neural network in the nervous system. They are located in the nervous system and help to ...

control. For fishes it has been demonstrated that chromatophores may respond directly to environmental stimuli like visible light, UV-radiation, temperature, pH, chemicals, etc. colour change helps individuals in becoming more or less visible and is important in agonistic displays and in camouflage. Some animals, including many butterflies and birds, have microscopic structures in scales, bristles or feathers which give them brilliant iridescent colours. Other animals including squid and some deep-sea fish can produce light, sometimes of different colours. Animals often use two or more of these mechanisms together to produce the colours and effects they need.

History

Classical antiquity

Animal coloration has been a topic of interest and

Animal coloration has been a topic of interest and research

Research is creative and systematic work undertaken to increase the stock of knowledge. It involves the collection, organization, and analysis of evidence to increase understanding of a topic, characterized by a particular attentiveness to ...

in biology

Biology is the scientific study of life and living organisms. It is a broad natural science that encompasses a wide range of fields and unifying principles that explain the structure, function, growth, History of life, origin, evolution, and ...

for centuries. In the classical era

Classical antiquity, also known as the classical era, classical period, classical age, or simply antiquity, is the period of cultural European history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD comprising the interwoven civilization ...

, Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

recorded that the octopus

An octopus (: octopuses or octopodes) is a soft-bodied, eight-limbed mollusc of the order Octopoda (, ). The order consists of some 300 species and is grouped within the class Cephalopoda with squids, cuttlefish, and nautiloids. Like oth ...

was able to change its coloration to match its background, and when it was alarmed.Aristotle (c. 350 BC). ''Historia Animalium''. IX, 622a: 2–10. Cited in Borrelli, Luciana; Gherardi, Francesca; Fiorito, Graziano (2006). ''A catalogue of body patterning in Cephalopoda''. Firenze University Press. Abstract

Early modern period

In his 1665 book ''Micrographia

''Micrographia: or Some Physiological Descriptions of Minute Bodies Made by Magnifying Glasses. With Observations and Inquiries Thereupon'' is a historically significant book by Robert Hooke about his observations through various lenses. It wa ...

'', Robert Hooke

Robert Hooke (; 18 July 16353 March 1703) was an English polymath who was active as a physicist ("natural philosopher"), astronomer, geologist, meteorologist, and architect. He is credited as one of the first scientists to investigate living ...

describes the "fantastical" (structural

A structure is an arrangement and organization of interrelated elements in a material object or system, or the object or system so organized. Material structures include man-made objects such as buildings and machines and natural objects such as ...

, not pigment) colours of the Peacock's feathers: Hooke, Robert (1665) ''Micrographia

''Micrographia: or Some Physiological Descriptions of Minute Bodies Made by Magnifying Glasses. With Observations and Inquiries Thereupon'' is a historically significant book by Robert Hooke about his observations through various lenses. It wa ...

''. Ch. 36 ('Observ. XXXVI. ''Of Peacoks, Ducks, and Other Feathers of Changeable Colours''.'). J. Martyn and J. Allestry, LondonFull text

.

Darwinian biology

According toCharles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

's 1859 theory of natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the Heredity, heritable traits characteristic of a population over generation ...

, features such as coloration evolved

Evolution is the change in the heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, re ...

by providing individual animals with a reproductive advantage. For example, individuals with slightly better camouflage than others of the same species

A species () is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes or mating types can produce fertile offspring, typically by sexual reproduction. It is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), ...

would, on average, leave more offspring. In his ''Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life'')The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by M ...

'', Darwin wrote: Darwin, Charles (1859). ''On the Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life'')The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by M ...

'', Ch. 4. John Murray, London. Reprinted 1985, Penguin Classics, Harmondsworth.

Henry Walter Bates

Henry Walter Bates (8 February 1825 – 16 February 1892) was an English natural history, naturalist and explorer who gave the first scientific account of mimicry in animals. He was most famous for his expedition to the Tropical rainforest ...

's 1863 book '' The Naturalist on the River Amazons'' describes his extensive studies of the insects in the Amazon basin, and especially the butterflies. He discovered that apparently similar butterflies often belonged to different families, with a harmless species mimicking a poisonous or bitter-tasting species to reduce its chance of being attacked by a predator, in the process now called after him, Batesian mimicry

Batesian mimicry is a form of mimicry where a harmless species has evolved to imitate the warning signals of a harmful species directed at a predator of them both. It is named after the English naturalist Henry Walter Bates, who worked on butt ...

. Bates, Henry Walter (1863). '' The Naturalist on the River Amazons''. John Murray, London.

Edward Bagnall Poulton

Sir Edward Bagnall Poulton, FRS HFRSE FLS (27 January 1856 – 20 November 1943) was a British evolutionary biologist, a lifelong advocate of natural selection through a period in which many scientists such as Reginald Punnett doubted its ...

's strongly Darwinian 1890 book '' The Colours of Animals, their meaning and use, especially considered in the case of insects'' argued the case for three aspects of animal coloration that are broadly accepted today but were controversial or wholly new at the time. It strongly supported Darwin's theory of sexual selection

Sexual selection is a mechanism of evolution in which members of one sex mate choice, choose mates of the other sex to mating, mate with (intersexual selection), and compete with members of the same sex for access to members of the opposite sex ...

, arguing that the obvious differences between male and female birds such as the argus pheasant were selected by the females, pointing out that bright male plumage was found only in species "which court by day". The book introduced the concept of frequency-dependent selection

Frequency-dependent selection is an evolutionary process by which the fitness (biology), fitness of a phenotype or genotype depends on the phenotype or genotype composition of a given population.

* In positive frequency-dependent selection, the fit ...

, as when edible mimics are less frequent than the distasteful models whose colours and patterns they copy. In the book, Poulton also coined the term aposematism

Aposematism is the Advertising in biology, advertising by an animal, whether terrestrial or marine, to potential predation, predators that it is not worth attacking or eating. This unprofitability may consist of any defenses which make the pr ...

for warning coloration, which he identified in widely differing animal groups including mammals (such as the skunk

Skunks are mammals in the family Mephitidae. They are known for their ability to spray a liquid with a strong, unpleasant scent from their anal glands. Different species of skunk vary in appearance from black-and-white to brown, cream or gi ...

), bees and wasps, beetles, and butterflies.

Frank Evers Beddard

Frank Evers Beddard FRS FRSE (19 June 1858 – 14 July 1925) was an English zoologist. He became a leading authority on annelids, including earthworms. He won the Linnean Medal in 1916 for his book on oligochaetes.

Life

Beddard was born in ...

's 1892 book, ''Animal Coloration

Animal coloration is the general appearance of an animal resulting from the reflection or emission of light from its surfaces. Some animals are brightly coloured, while others are hard to see. In some species, such as the peafowl, the male h ...

'', acknowledged that natural selection existed but examined its application to camouflage, mimicry and sexual selection very critically. The book was in turn roundly criticised by Poulton.

Abbott Handerson Thayer's 1909 book '' Concealing-Coloration in the Animal Kingdom'', completed by his son Gerald H. Thayer, argued correctly for the widespread use of

Abbott Handerson Thayer's 1909 book '' Concealing-Coloration in the Animal Kingdom'', completed by his son Gerald H. Thayer, argued correctly for the widespread use of crypsis

In ecology, crypsis is the ability of an animal or a plant to avoid observation or detection by other animals. It may be part of a predation strategy or an antipredator adaptation. Methods include camouflage, nocturnality, subterranean life ...

among animals, and in particular described and explained countershading

Countershading, or Thayer's law, is a method of camouflage in which animal coloration, an animal's coloration is darker on the top or upper side and lighter on the underside of the body. This pattern is found in many species of mammals, reptile ...

for the first time. However, the Thayers spoilt their case by arguing that camouflage was the sole purpose of animal coloration, which led them to claim that even the brilliant pink plumage of the flamingo

Flamingos or flamingoes () are a type of wading bird in the family Phoenicopteridae, which is the only extant family in the order Phoenicopteriformes. There are four flamingo species distributed throughout the Americas (including the Caribbe ...

or the roseate spoonbill

The roseate spoonbill (''Platalea ajaja'') is a social wading bird of the ibis and spoonbill family, Threskiornithidae. It is a resident breeder in both South and North America. The roseate spoonbill's pink color is diet-derived, consisting of ...

was cryptic—against the momentarily pink sky at dawn or dusk. As a result, the book was mocked by critics including Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

as having "pushed he "doctrine" of concealing colorationto such a fantastic extreme and to include such wild absurdities as to call for the application of common sense thereto."

Hugh Bamford Cott's 500-page book '' Adaptive Coloration in Animals'', published in wartime 1940, systematically described the principles of camouflage and mimicry. The book contains hundreds of examples, over a hundred photographs and Cott's own accurate and artistic drawings, and 27 pages of references. Cott focussed especially on "maximum disruptive contrast", the kind of patterning used in military camouflage such as disruptive pattern material. Indeed, Cott describes such applications:

Animal coloration provided important early evidence for evolution by natural selection, at a time when little direct evidence was available.

Evolutionary reasons for animal coloration

Camouflage

One of the pioneers of research into animal coloration,Edward Bagnall Poulton

Sir Edward Bagnall Poulton, FRS HFRSE FLS (27 January 1856 – 20 November 1943) was a British evolutionary biologist, a lifelong advocate of natural selection through a period in which many scientists such as Reginald Punnett doubted its ...

Poulton, Edward Bagnall (1890). '' The Colours of Animals, their meaning and use, especially considered in the case of insects''. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner. London. pp. 331–334 classified the forms of protective coloration, in a way which is still helpful. He described: protective resemblance; aggressive resemblance; adventitious protection; and variable protective resemblance.Forbes, 2009. pp. 50–51 These are covered in turn below.

mimesis

Mimesis (; , ''mīmēsis'') is a term used in literary criticism and philosophy that carries a wide range of meanings, including '' imitatio'', imitation, similarity, receptivity, representation, mimicry, the act of expression, the act of ...

, where the whole animal looks like some other object, for example when a caterpillar resembles a twig or a bird dropping. In general protective resemblance, now called crypsis

In ecology, crypsis is the ability of an animal or a plant to avoid observation or detection by other animals. It may be part of a predation strategy or an antipredator adaptation. Methods include camouflage, nocturnality, subterranean life ...

, the animal's texture blends with the background, for example when a moth's colour and pattern blend in with tree bark.

Aggressive resemblance is used by

Aggressive resemblance is used by predator

Predation is a biological interaction in which one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common List of feeding behaviours, feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation ...

s or parasite

Parasitism is a Symbiosis, close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives (at least some of the time) on or inside another organism, the Host (biology), host, causing it some harm, and is Adaptation, adapted str ...

s. In special aggressive resemblance, the animal looks like something else, luring the prey or host to approach, for example when a flower mantis

Flower mantises are praying mantises that use a special form of camouflage referred to as aggressive mimicry, which they not only use to attract prey, but avoid predators as well. These insects have specific colorations and behaviors that mimic ...

resembles a particular kind of flower, such as an orchid

Orchids are plants that belong to the family Orchidaceae (), a diverse and widespread group of flowering plants with blooms that are often colourful and fragrant. Orchids are cosmopolitan plants that are found in almost every habitat on Eart ...

. In general aggressive resemblance, the predator or parasite blends in with the background, for example when a leopard

The leopard (''Panthera pardus'') is one of the five extant cat species in the genus ''Panthera''. It has a pale yellowish to dark golden fur with dark spots grouped in rosettes. Its body is slender and muscular reaching a length of with a ...

is hard to see in long grass.

For adventitious protection, an animal uses materials such as twigs, sand, or pieces of shell to conceal its outline, for example when a caddis fly larva builds a decorated case, or when a decorator crab decorates its back with seaweed, sponges and stones.

In variable protective resemblance, an animal such as a chameleon

Chameleons or chamaeleons (Family (biology), family Chamaeleonidae) are a distinctive and highly specialized clade of Old World lizards with 200 species described as of June 2015. The members of this Family (biology), family are best known for ...

, flatfish, squid or octopus

An octopus (: octopuses or octopodes) is a soft-bodied, eight-limbed mollusc of the order Octopoda (, ). The order consists of some 300 species and is grouped within the class Cephalopoda with squids, cuttlefish, and nautiloids. Like oth ...

changes its skin pattern and colour using special chromatophore

Chromatophores are cells that produce color, of which many types are pigment-containing cells, or groups of cells, found in a wide range of animals including amphibians, fish, reptiles, crustaceans and cephalopod

A cephalopod is any member o ...

cells to resemble whatever background it is currently resting on (as well as for signalling

A signal is both the process and the result of transmission of data over some media accomplished by embedding some variation. Signals are important in multiple subject fields including signal processing, information theory and biology.

In ...

).

The main mechanisms to create the resemblances described by Poulton – whether in nature or in military applications – are crypsis

In ecology, crypsis is the ability of an animal or a plant to avoid observation or detection by other animals. It may be part of a predation strategy or an antipredator adaptation. Methods include camouflage, nocturnality, subterranean life ...

, blending into the background so as to become hard to see (this covers both special and general resemblance); disruptive patterning, using colour and pattern to break up the animal's outline, which relates mainly to general resemblance; mimesis, resembling other objects of no special interest to the observer, which relates to special resemblance; countershading

Countershading, or Thayer's law, is a method of camouflage in which animal coloration, an animal's coloration is darker on the top or upper side and lighter on the underside of the body. This pattern is found in many species of mammals, reptile ...

, using graded colour to create the illusion of flatness, which relates mainly to general resemblance; and counterillumination, producing light to match the background, notably in some species of squid

A squid (: squid) is a mollusc with an elongated soft body, large eyes, eight cephalopod limb, arms, and two tentacles in the orders Myopsida, Oegopsida, and Bathyteuthida (though many other molluscs within the broader Neocoleoidea are also ...

.

Countershading was first described by the American artist Abbott Handerson Thayer, a pioneer in the theory of animal coloration. Thayer observed that whereas a painter takes a flat canvas and uses coloured paint to create the illusion of solidity by painting in shadows, animals such as deer are often darkest on their backs, becoming lighter towards the belly, creating (as zoologist Hugh Cott

Hugh Bamford Cott (6 July 1900 – 18 April 1987) was a British zoologist, an authority on both natural and military camouflage, and a scientific illustrator and photographer. Many of his field studies took place in Africa, where he was especia ...

observed) the illusion of flatness,Cott, H. B. 1940 and against a matching background, of invisibility. Thayer's observation "Animals are painted by Nature, darkest on those parts which tend to be most lighted by the sky's light, and ''vice versa''" is called ''Thayer's Law''.Forbes, 2009. pp. 72–73

Signalling

Colour is widely used for signalling in animals as diverse as birds and shrimps. Signalling encompasses at least three purposes: *advertising

Advertising is the practice and techniques employed to bring attention to a Product (business), product or Service (economics), service. Advertising aims to present a product or service in terms of utility, advantages, and qualities of int ...

, to signal a capability or service to other animals, whether within a species or not

* sexual selection, where members of one sex choose to mate with suitably coloured members of the other sex, thus driving the development of such colours

* warning, to signal that an animal is harmful, for example can sting, is poisonous or is bitter-tasting. Warning signals may be mimicked truthfully or untruthfully.

Advertising services

Advertising coloration can signal the services an animal offers to other animals. These may be of the same species, as in

Advertising coloration can signal the services an animal offers to other animals. These may be of the same species, as in sexual selection

Sexual selection is a mechanism of evolution in which members of one sex mate choice, choose mates of the other sex to mating, mate with (intersexual selection), and compete with members of the same sex for access to members of the opposite sex ...

, or of different species, as in cleaning symbiosis

Cleaning is the process of removing unwanted substances, such as dirt, infectious agents, and other impurities, from an object or environment. Cleaning is often performed for beauty, aesthetic, hygiene, hygienic, Function (engineering), function ...

. Signals, which often combine colour and movement, may be understood by many different species; for example, the cleaning stations of the banded coral shrimp ''Stenopus hispidus

''Stenopus hispidus'' is a shrimp-like decapod crustacean belonging to the infraorder Stenopodidea. Common names include coral banded shrimp and banded cleaner shrimp.

Distribution

''Stenopus hispidus'' has a pan-tropical distribution, extendi ...

'' are visited by different species of fish, and even by reptiles such as hawksbill sea turtle

The hawksbill sea turtle (''Eretmochelys imbricata'') is a critically endangered sea turtle belonging to the family Cheloniidae. It is the only extant species in the genus ''Eretmochelys''. The species has a global distribution that is largel ...

s.

Sexual selection

Darwin observed that the males of some species, such as birds-of-paradise, were very different from the females.

Darwin explained such male-female differences in his theory of sexual selection in his book ''

Darwin observed that the males of some species, such as birds-of-paradise, were very different from the females.

Darwin explained such male-female differences in his theory of sexual selection in his book ''The Descent of Man

''The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex'' is a book by English natural history, naturalist Charles Darwin, first published in 1871, which applies evolutionary theory to human evolution, and details his theory of sexual selection, ...

''. Once the females begin to select males according to any particular characteristic, such as a long tail or a coloured crest, that characteristic is emphasized more and more in the males. Eventually all the males will have the characteristics that the females are sexually selecting for, as only those males can reproduce. This mechanism is powerful enough to create features that are strongly disadvantageous to the males in other ways. For example, some male birds-of-paradise

The birds-of-paradise are members of the family Paradisaeidae of the order Passeriformes. The majority of species are found in eastern Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, and eastern Australia. The family has 45 species in 17 genera. The members of this ...

have wing or tail streamers that are so long that they impede flight, while their brilliant colours may make the males more vulnerable to predators. In the extreme, sexual selection may drive species to extinction, as has been argued for the enormous horns of the male Irish elk, which may have made it difficult for mature males to move and feed.

Different forms of sexual selection are possible, including rivalry among males, and selection of females by males.

Warning

Warning coloration (aposematism) is effectively the "opposite" of camouflage, and a special case of advertising. Its function is to make the animal, for example a wasp or a coral snake, highly conspicuous to potential predators, so that it is noticed, remembered, and then avoided. As Peter Forbes observes, "Human warning signs employ the same colours – red, yellow, black, and white – that nature uses to advertise dangerous creatures."Forbes, 2009. p. 52 and plate 24. Warning colours work by being associated by potential predators with something that makes the warning coloured animal unpleasant or dangerous. This can be achieved in several ways, by being any combination of:

Warning coloration (aposematism) is effectively the "opposite" of camouflage, and a special case of advertising. Its function is to make the animal, for example a wasp or a coral snake, highly conspicuous to potential predators, so that it is noticed, remembered, and then avoided. As Peter Forbes observes, "Human warning signs employ the same colours – red, yellow, black, and white – that nature uses to advertise dangerous creatures."Forbes, 2009. p. 52 and plate 24. Warning colours work by being associated by potential predators with something that makes the warning coloured animal unpleasant or dangerous. This can be achieved in several ways, by being any combination of:

* distasteful, for example caterpillars, pupae and adults of the cinnabar moth, the

* distasteful, for example caterpillars, pupae and adults of the cinnabar moth, the monarch

A monarch () is a head of stateWebster's II New College Dictionary. "Monarch". Houghton Mifflin. Boston. 2001. p. 707. Life tenure, for life or until abdication, and therefore the head of state of a monarchy. A monarch may exercise the highest ...

and the variable checkerspot butterfly have bitter-tasting chemicals in their blood. One monarch contains more than enough digitalis

''Digitalis'' ( or ) is a genus of about 20 species of herbaceous perennial plants, shrubs, and Biennial plant, biennials, commonly called foxgloves.

''Digitalis'' is native to Europe, Western Asia, and northwestern Africa. The flowers are ...

-like toxin

A toxin is a naturally occurring poison produced by metabolic activities of living cells or organisms. They occur especially as proteins, often conjugated. The term was first used by organic chemist Ludwig Brieger (1849–1919), derived ...

to kill a cat, while a monarch extract makes starlings vomit.

* foul-smelling, for example the skunk

Skunks are mammals in the family Mephitidae. They are known for their ability to spray a liquid with a strong, unpleasant scent from their anal glands. Different species of skunk vary in appearance from black-and-white to brown, cream or gi ...

can eject a liquid with a long-lasting and powerful odourCott, 1940, p. 241, citing Gilbert White

Gilbert White (18 July 1720 – 26 June 1793) was a "parson-naturalist", a pioneering English naturalist, ecologist, and ornithologist. He is best known for his '' Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne''.

Life

White was born on 18 Jul ...

.

* aggressive and able to defend itself, for example honey badger

The honey badger (''Mellivora capensis''), also known as the ratel ( or ), is a mammal widely distributed across Africa, Southwest Asia, and the Indian subcontinent. It is the only living species in both the genus ''Mellivora'' and the subfami ...

s.

* venomous, for example a wasp

A wasp is any insect of the narrow-waisted suborder Apocrita of the order Hymenoptera which is neither a bee nor an ant; this excludes the broad-waisted sawflies (Symphyta), which look somewhat like wasps, but are in a separate suborder ...

can deliver a painful sting, while snakes like the viper

Vipers are snakes in the family Viperidae, found in most parts of the world, except for Antarctica, Australia, Hawaii, Madagascar, New Zealand, Ireland, and various other isolated islands. They are venomous and have long (relative to non-vipe ...

or coral snake

Coral snakes are a large group of elapid snakes that can be divided into two distinct groups, the Old World coral snakes and New World coral snakes. There are 27 species of Old World coral snakes, in three genera ('' Calliophis'', '' Hemibungar ...

can deliver a fatal bite.

Warning coloration can succeed either through inborn behaviour (instinct

Instinct is the inherent inclination of a living organism towards a particular complex behaviour, containing innate (inborn) elements. The simplest example of an instinctive behaviour is a fixed action pattern (FAP), in which a very short to me ...

) on the part of potential predators, or through a learned avoidance. Either can lead to various forms of mimicry. Experiments show that avoidance is learned in bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class (biology), class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the Oviparity, laying of Eggshell, hard-shelled eggs, a high Metabolism, metabolic rate, a fou ...

s, mammal

A mammal () is a vertebrate animal of the Class (biology), class Mammalia (). Mammals are characterised by the presence of milk-producing mammary glands for feeding their young, a broad neocortex region of the brain, fur or hair, and three ...

s, lizards

Lizard is the common name used for all squamate reptiles other than snakes (and to a lesser extent amphisbaenians), encompassing over 7,000 species, ranging across all continents except Antarctica, as well as most oceanic island chains. The ...

, and amphibian

Amphibians are ectothermic, anamniote, anamniotic, tetrapod, four-limbed vertebrate animals that constitute the class (biology), class Amphibia. In its broadest sense, it is a paraphyletic group encompassing all Tetrapod, tetrapods, but excl ...

s, but that some birds such as great tit

The great tit (''Parus major'') is a small passerine bird in the tit family Paridae. It is a widespread and common species throughout Europe, the Middle East, Central Asia and east across the Palearctic to the Amur River, south to parts of No ...

s have inborn avoidance of certain colours and patterns such as black and yellow stripes.

Mimicry

Mimicry means that one species of animal resembles another species closely enough to deceive predators. To evolve, the mimicked species must have warning coloration, because appearing to be bitter-tasting or dangerous gives

Mimicry means that one species of animal resembles another species closely enough to deceive predators. To evolve, the mimicked species must have warning coloration, because appearing to be bitter-tasting or dangerous gives natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the Heredity, heritable traits characteristic of a population over generation ...

something to work on. Once a species has a slight, chance, resemblance to a warning coloured species, natural selection can drive its colours and patterns towards more perfect mimicry. There are numerous possible mechanisms, of which the best known are:

* Batesian mimicry

Batesian mimicry is a form of mimicry where a harmless species has evolved to imitate the warning signals of a harmful species directed at a predator of them both. It is named after the English naturalist Henry Walter Bates, who worked on butt ...

, where an edible species resembles a distasteful or dangerous species. This is most common in insects such as butterflies

Butterflies are winged insects from the lepidopteran superfamily Papilionoidea, characterized by large, often brightly coloured wings that often fold together when at rest, and a conspicuous, fluttering flight. The oldest butterfly fossi ...

. A familiar example is the resemblance of harmless hoverflies

Hoverflies, also called flower flies or syrphids, make up the insect family (biology), family Syrphidae. As their common name suggests, they are often seen Hover (behaviour), hovering or nectaring at flowers; the adults of many species feed main ...

(which have no sting) to bees

Bees are winged insects closely related to wasps and ants, known for their roles in pollination and, in the case of the best-known bee species, the western honey bee, for producing honey. Bees are a monophyletic lineage within the superfamil ...

.

* Müllerian mimicry

Müllerian mimicry is a natural phenomenon in which two or more well-defended species, often foul-tasting and sharing common predators, have come to mimicry, mimic each other's honest signal, honest aposematism, warning signals, to their mutuali ...

, where two or more distasteful or dangerous animal species resemble each other. This is most common among insects such as wasps

A wasp is any insect of the narrow-waisted suborder Apocrita of the order Hymenoptera which is neither a bee nor an ant; this excludes the broad-waisted sawflies (Symphyta), which look somewhat like wasps, but are in a separate suborder. Th ...

and bees (hymenoptera

Hymenoptera is a large order of insects, comprising the sawflies, wasps, bees, and ants. Over 150,000 living species of Hymenoptera have been described, in addition to over 2,000 extinct ones. Many of the species are parasitic.

Females typi ...

).

''Batesian mimicry'' was first described by the pioneering naturalist Henry W. Bates. When an edible prey animal comes to resemble, even slightly, a distasteful animal, natural selection favours those individuals that even very slightly better resemble the distasteful species. This is because even a small degree of protection reduces predation and increases the chance that an individual mimic will survive and reproduce. For example, many species of hoverfly are coloured black and yellow like bees, and are in consequence avoided by birds (and people).

''Müllerian mimicry'' was first described by the pioneering naturalist Fritz Müller

Johann Friedrich Theodor Müller (; 31 March 182221 May 1897), better known as Fritz Müller (), and also as Müller-Desterro, was a German biologist who emigrated to southern Brazil, where he lived in and near the city of Blumenau, Santa Cata ...

. When a distasteful animal comes to resemble a more common distasteful animal, natural selection favours individuals that even very slightly better resemble the target. For example, many species of stinging wasp and bee are similarly coloured black and yellow. Müller's explanation of the mechanism for this was one of the first uses of mathematics in biology. He argued that a predator, such as a young bird, must attack at least one insect, say a wasp, to learn that the black and yellow colours mean a stinging insect. If bees were differently coloured, the young bird would have to attack one of them also. But when bees and wasps resemble each other, the young bird need only attack one from the whole group to learn to avoid all of them. So, fewer bees are attacked if they mimic wasps; the same applies to wasps that mimic bees. The result is mutual resemblance for mutual protection.

Distraction

Startle

Some animals such as manymoth

Moths are a group of insects that includes all members of the order Lepidoptera that are not Butterfly, butterflies. They were previously classified as suborder Heterocera, but the group is Paraphyly, paraphyletic with respect to butterflies (s ...

s, mantis

Mantises are an order (Mantodea) of insects that contains over 2,400 species in about 460 genera in 33 families. The largest family is the Mantidae ("mantids"). Mantises are distributed worldwide in temperate a ...

es and grasshopper

Grasshoppers are a group of insects belonging to the suborder Caelifera. They are amongst what are possibly the most ancient living groups of chewing herbivorous insects, dating back to the early Triassic around 250 million years ago.

Grassh ...

s, have a repertoire of threatening or startling behaviour, such as suddenly displaying conspicuous eyespots or patches of bright and contrasting colours, so as to scare off or momentarily distract a predator. This gives the prey animal an opportunity to escape. The behaviour is deimatic (startling) rather than aposematic as these insects are palatable to predators, so the warning colours are a bluff, not an honest signal

Within evolutionary biology, signalling theory is a body of theoretical work examining communication between individuals, both within species and across species. The central question is how organisms with conflicting interests, such as in se ...

.

Motion dazzle

Some prey animals such aszebra

Zebras (, ) (subgenus ''Hippotigris'') are African equines with distinctive black-and-white striped coats. There are three living species: Grévy's zebra (''Equus grevyi''), the plains zebra (''E. quagga''), and the mountain zebra (''E. ...

are marked with high-contrast patterns which possibly help to confuse their predators, such as lion

The lion (''Panthera leo'') is a large Felidae, cat of the genus ''Panthera'', native to Sub-Saharan Africa and India. It has a muscular, broad-chested body (biology), body; a short, rounded head; round ears; and a dark, hairy tuft at the ...

s, during a chase. The bold stripes of a herd of running zebra have been claimed make it difficult for predators to estimate the prey's speed and direction accurately, or to identify individual animals, giving the prey an improved chance of escape. Since dazzle patterns (such as the zebra's stripes) make animals harder to catch when moving, but easier to detect when stationary, there is an evolutionary trade-off between dazzle and camouflage

Camouflage is the use of any combination of materials, coloration, or illumination for concealment, either by making animals or objects hard to see, or by disguising them as something else. Examples include the leopard's spotted coat, the b ...

. There is evidence that the zebra's stripes could provide some protection from flies and biting insects.

Physical protection

Many animals have dark pigments such asmelanin

Melanin (; ) is a family of biomolecules organized as oligomers or polymers, which among other functions provide the pigments of many organisms. Melanin pigments are produced in a specialized group of cells known as melanocytes.

There are ...

in their skin

Skin is the layer of usually soft, flexible outer tissue covering the body of a vertebrate animal, with three main functions: protection, regulation, and sensation.

Other animal coverings, such as the arthropod exoskeleton, have different ...

, eye

An eye is a sensory organ that allows an organism to perceive visual information. It detects light and converts it into electro-chemical impulses in neurons (neurones). It is part of an organism's visual system.

In higher organisms, the ey ...

s and fur

A fur is a soft, thick growth of hair that covers the skin of almost all mammals. It consists of a combination of oily guard hair on top and thick underfur beneath. The guard hair keeps moisture from reaching the skin; the underfur acts as an ...

to protect themselves against sunburn

Sunburn is a form of radiation burn that affects living tissue, such as skin, that results from an overexposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation, usually from the Sun. Common symptoms in humans and other animals include red or reddish skin tha ...

(damage to living tissues caused by ultraviolet

Ultraviolet radiation, also known as simply UV, is electromagnetic radiation of wavelengths of 10–400 nanometers, shorter than that of visible light, but longer than X-rays. UV radiation is present in sunlight and constitutes about 10% of ...

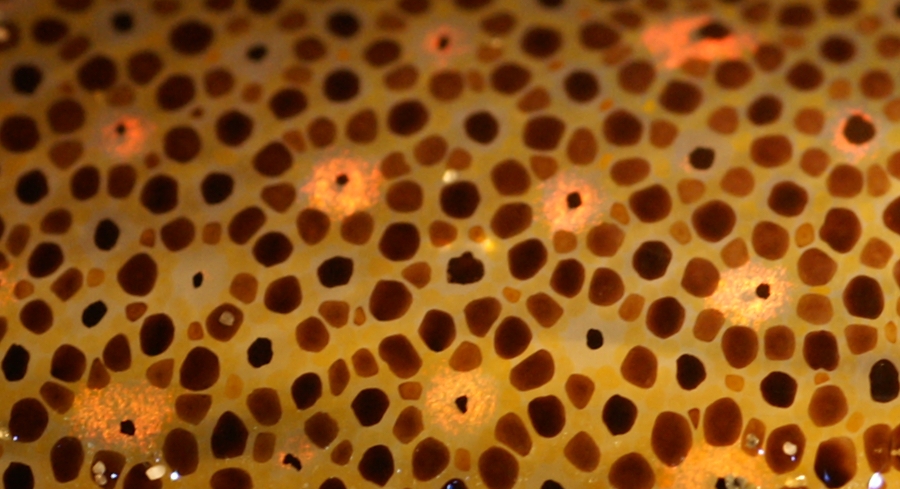

light). Another example of photoprotective pigments are the GFP-like proteins in some coral

Corals are colonial marine invertebrates within the subphylum Anthozoa of the phylum Cnidaria. They typically form compact Colony (biology), colonies of many identical individual polyp (zoology), polyps. Coral species include the important Coral ...

s. In some jellyfish

Jellyfish, also known as sea jellies or simply jellies, are the #Life cycle, medusa-phase of certain gelatinous members of the subphylum Medusozoa, which is a major part of the phylum Cnidaria. Jellyfish are mainly free-swimming marine animal ...

, rhizostomins have also been hypothesized to protect against ultraviolet damage.

Temperature regulation

Some frogs such as '' Bokermannohyla alvarengai'', which basks in sunlight, lighten their skin colour when hot (and darkens when cold), making their skin reflect more heat and so avoid overheating.

Some frogs such as '' Bokermannohyla alvarengai'', which basks in sunlight, lighten their skin colour when hot (and darkens when cold), making their skin reflect more heat and so avoid overheating.

Incidental coloration

Some animals are coloured purely incidentally because their blood contains pigments. For example, amphibians like the

Some animals are coloured purely incidentally because their blood contains pigments. For example, amphibians like the olm

The olm () or proteus (''Proteus anguinus'') is an aquatic salamander which is the only species in the genus ''Proteus'' of the family Proteidae and the only exclusively cave-dwelling chordate species found in Europe; the family's other extant g ...

that live in caves may be largely colorless as colour has no function in that environment, but they show some red because of the haem pigment in their red blood cells, needed to carry oxygen. They also have a little orange coloured riboflavin

Riboflavin, also known as vitamin B2, is a vitamin found in food and sold as a dietary supplement. It is essential to the formation of two major coenzymes, flavin mononucleotide and flavin adenine dinucleotide. These coenzymes are involved in ...

in their skin. Human albino

Albinism is the congenital absence of melanin in an animal or plant resulting in white hair, feathers, scales and skin and reddish pink or blue eyes. Individuals with the condition are referred to as albinos.

Varied use and interpretation of ...

s and people with fair skin have a similar colour for the same reason.

Mechanisms of colour production in animals

Animal coloration may be the result of any combination of

Animal coloration may be the result of any combination of pigments

A pigment is a powder used to add or alter color or change visual appearance. Pigments are completely or nearly solubility, insoluble and reactivity (chemistry), chemically unreactive in water or another medium; in contrast, dyes are colored sub ...

, chromatophores

Chromatophores are cells that produce color, of which many types are Biological pigment, pigment-containing cells, or groups of cells, found in a wide range of animals including amphibians, fish, reptiles, crustaceans and cephalopods. Mammals an ...

, structural coloration

Structural coloration in animals, and a few plants, is the production of colour by microscopically structured surfaces fine enough to interfere with visible light instead of Biological pigment, pigments, although some structural coloration occu ...

and bioluminescence

Bioluminescence is the emission of light during a chemiluminescence reaction by living organisms. Bioluminescence occurs in multifarious organisms ranging from marine vertebrates and invertebrates, as well as in some Fungus, fungi, microorgani ...

.

Coloration by pigments

Pigments are coloured chemicals (such as

Pigments are coloured chemicals (such as melanin

Melanin (; ) is a family of biomolecules organized as oligomers or polymers, which among other functions provide the pigments of many organisms. Melanin pigments are produced in a specialized group of cells known as melanocytes.

There are ...

) in animal tissues. For example, the Arctic fox

The Arctic fox (''Vulpes lagopus''), also known as the white fox, polar fox, or snow fox, is a small species of fox native to the Arctic regions of the Northern Hemisphere and common throughout the Tundra#Arctic tundra, Arctic tundra biome. I ...

has a white coat in winter (containing little pigment), and a brown coat in summer (containing more pigment), an example of seasonal camouflage

A polyphenic trait is a trait for which multiple, discrete phenotypes can arise from a single genotype as a result of differing environmental conditions. It is therefore a special case of phenotypic plasticity.

There are several types of polyphen ...

(a polyphenism

A polyphenic trait is a trait for which multiple, discrete phenotypes can arise from a single genotype as a result of differing environmental conditions. It is therefore a special case of phenotypic plasticity.

There are several types of polyphen ...

). Many animals, including mammal

A mammal () is a vertebrate animal of the Class (biology), class Mammalia (). Mammals are characterised by the presence of milk-producing mammary glands for feeding their young, a broad neocortex region of the brain, fur or hair, and three ...

s, bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class (biology), class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the Oviparity, laying of Eggshell, hard-shelled eggs, a high Metabolism, metabolic rate, a fou ...

s, and amphibian

Amphibians are ectothermic, anamniote, anamniotic, tetrapod, four-limbed vertebrate animals that constitute the class (biology), class Amphibia. In its broadest sense, it is a paraphyletic group encompassing all Tetrapod, tetrapods, but excl ...

s, are unable to synthesize most of the pigments that colour their fur or feathers, other than the brown or black melanins that give many mammals their earth tones. For example, the bright yellow of an American goldfinch

The American goldfinch (''Spinus tristis'') is a small North American bird in the finch Family (biology), family. It is Bird migration, migratory, ranging from mid-Alberta to North Carolina during the breeding season, and from just south of th ...

, the startling orange of a juvenile red-spotted newt, the deep red of a cardinal

Cardinal or The Cardinal most commonly refers to

* Cardinalidae, a family of North and South American birds

**''Cardinalis'', genus of three species in the family Cardinalidae

***Northern cardinal, ''Cardinalis cardinalis'', the common cardinal of ...

and the pink of a flamingo

Flamingos or flamingoes () are a type of wading bird in the family Phoenicopteridae, which is the only extant family in the order Phoenicopteriformes. There are four flamingo species distributed throughout the Americas (including the Caribbe ...

are all produced by carotenoid

Carotenoids () are yellow, orange, and red organic pigments that are produced by plants and algae, as well as several bacteria, archaea, and fungi. Carotenoids give the characteristic color to pumpkins, carrots, parsnips, corn, tomatoes, cana ...

pigments synthesized by plants. In the case of the flamingo, the bird eats pink shrimps, which are themselves unable to synthesize carotenoids. The shrimps derive their body colour from microscopic red algae, which like most plants are able to create their own pigments, including both carotenoids and (green) chlorophyll

Chlorophyll is any of several related green pigments found in cyanobacteria and in the chloroplasts of algae and plants. Its name is derived from the Greek words (, "pale green") and (, "leaf"). Chlorophyll allows plants to absorb energy ...

. Animals that eat green plants do not become green, however, as chlorophyll does not survive digestion.

Variable coloration by chromatophores

cuttlefish

Cuttlefish, or cuttles, are Marine (ocean), marine Mollusca, molluscs of the order (biology), suborder Sepiina. They belong to the class (biology), class Cephalopoda which also includes squid, octopuses, and nautiluses. Cuttlefish have a unique ...

and chameleon

Chameleons or chamaeleons (Family (biology), family Chamaeleonidae) are a distinctive and highly specialized clade of Old World lizards with 200 species described as of June 2015. The members of this Family (biology), family are best known for ...

s can rapidly change their appearance, both for camouflage and for signalling, as Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

first noted over 2000 years ago:

Cephalopod

A cephalopod is any member of the molluscan Taxonomic rank, class Cephalopoda (Greek language, Greek plural , ; "head-feet") such as a squid, octopus, cuttlefish, or nautilus. These exclusively marine animals are characterized by bilateral symm ...

molluscs

Mollusca is a phylum of protostome, protostomic invertebrate animals, whose members are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 76,000 extant taxon, extant species of molluscs are recognized, making it the second-largest animal phylum ...

like squid

A squid (: squid) is a mollusc with an elongated soft body, large eyes, eight cephalopod limb, arms, and two tentacles in the orders Myopsida, Oegopsida, and Bathyteuthida (though many other molluscs within the broader Neocoleoidea are also ...

can voluntarily change their coloration by contracting or relaxationg small muscles around their chromatophores. The energy cost of the complete activation of the chromatophore system is very high, equalling nearly as much as all the energy used by an octopus at rest. Amphibian

Amphibians are ectothermic, anamniote, anamniotic, tetrapod, four-limbed vertebrate animals that constitute the class (biology), class Amphibia. In its broadest sense, it is a paraphyletic group encompassing all Tetrapod, tetrapods, but excl ...

s such as frogs have three kinds of star-shaped chromatophore cells in separate layers of their skin. The top layer contains ' xanthophores' with orange, red, or yellow pigments; the middle layer contains ' iridophores' with a silvery light-reflecting pigment; while the bottom layer contains 'melanophores

Chromatophores are cells that produce color, of which many types are pigment-containing cells, or groups of cells, found in a wide range of animals including amphibians, fish, reptiles, crustaceans and cephalopods. Mammals and birds, in contrast ...

' with dark melanin.

Structural coloration

While many animals are unable to synthesize carotenoid pigments to create red and yellow surfaces, the green and blue colours of bird feathers and insect carapaces are usually not produced by pigments at all, but by structural coloration. Structural coloration means the production of colour by microscopically-structured surfaces fine enough to interfere with

While many animals are unable to synthesize carotenoid pigments to create red and yellow surfaces, the green and blue colours of bird feathers and insect carapaces are usually not produced by pigments at all, but by structural coloration. Structural coloration means the production of colour by microscopically-structured surfaces fine enough to interfere with visible light

Light, visible light, or visible radiation is electromagnetic radiation that can be perceived by the human eye. Visible light spans the visible spectrum and is usually defined as having wavelengths in the range of 400–700 nanometres (nm ...

, sometimes in combination with pigments: for example, peacock

Peafowl is a common name for two bird species of the genus '' Pavo'' and one species of the closely related genus '' Afropavo'' within the tribe Pavonini of the family Phasianidae (the pheasants and their allies). Male peafowl are referred t ...

tail feathers are pigmented brown, but their structure makes them appear blue, turquoise and green. Structural coloration can produce the most brilliant colours, often iridescent

Iridescence (also known as goniochromism) is the phenomenon of certain surfaces that appear gradually to change colour as the angle of view or the angle of illumination changes. Iridescence is caused by wave interference of light in microstruc ...

. For example, the blue/green gloss on the plumage of bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class (biology), class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the Oviparity, laying of Eggshell, hard-shelled eggs, a high Metabolism, metabolic rate, a fou ...

s such as ducks

Duck is the common name for numerous species of waterfowl in the family (biology), family Anatidae. Ducks are generally smaller and shorter-necked than swans and goose, geese, which are members of the same family. Divided among several subfam ...

, and the purple/blue/green/red colours of many beetles

Beetles are insects that form the Taxonomic rank, order Coleoptera (), in the superorder Holometabola. Their front pair of wings are hardened into wing-cases, elytra, distinguishing them from most other insects. The Coleoptera, with about 40 ...

and butterflies

Butterflies are winged insects from the lepidopteran superfamily Papilionoidea, characterized by large, often brightly coloured wings that often fold together when at rest, and a conspicuous, fluttering flight. The oldest butterfly fossi ...

are created by structural coloration. Animals use several methods to produce structural colour, as described in the table.

Bioluminescence

Bioluminescence is the production of

Bioluminescence is the production of light

Light, visible light, or visible radiation is electromagnetic radiation that can be visual perception, perceived by the human eye. Visible light spans the visible spectrum and is usually defined as having wavelengths in the range of 400– ...

, such as by the photophore

A photophore is a specialized anatomical structure found in a variety of organisms that emits light through the process of boluminescence. This light may be produced endogenously by the organism itself (symbiotic) or generated through a mut ...

s of marine animals, and the tails of glow-worms and fireflies

The Lampyridae are a family of elateroid beetles with more than 2,000 described species, many of which are light-emitting. They are soft-bodied beetles commonly called fireflies, lightning bugs, or glowworms for their conspicuous production ...

. Bioluminescence, like other forms of metabolism

Metabolism (, from ''metabolē'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run cellular processes; the co ...

, releases energy derived from the chemical energy of food. A pigment, luciferin

Luciferin () is a generic term for the light-emitting chemical compound, compound found in organisms that generate bioluminescence. Luciferins typically undergo an enzyme-catalyzed reaction with Oxygen, molecular oxygen. The resulting transforma ...

is catalysed by the enzyme

An enzyme () is a protein that acts as a biological catalyst by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrate (chemistry), substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different mol ...

luciferase

Luciferase is a generic term for the class of oxidative enzymes that produce bioluminescence, and is usually distinguished from a photoprotein. The name was first used by Raphaël Dubois who invented the words ''luciferin'' and ''luciferase'' ...

to react with oxygen, releasing light. Comb jellies

Ctenophora (; : ctenophore ) is a phylum of marine invertebrates, commonly known as comb jellies, that inhabit sea waters worldwide. They are notable for the groups of cilia they use for swimming (commonly referred to as "combs"), and they are ...

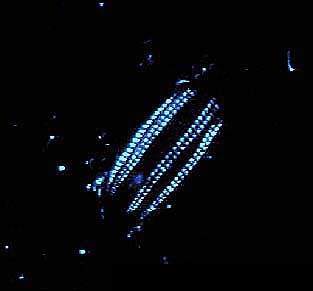

such as ''Euplokamis'' are bioluminescent, creating blue and green light, especially when stressed; when disturbed, they secrete an ink which luminesces in the same colours. Since comb jellies are not very sensitive to light, their bioluminescence is unlikely to be used to signal to other members of the same species (e.g. to attract mates or repel rivals); more likely, the light helps to distract predators or parasites. Some species of squid

A squid (: squid) is a mollusc with an elongated soft body, large eyes, eight cephalopod limb, arms, and two tentacles in the orders Myopsida, Oegopsida, and Bathyteuthida (though many other molluscs within the broader Neocoleoidea are also ...

have light-producing organs (photophore

A photophore is a specialized anatomical structure found in a variety of organisms that emits light through the process of boluminescence. This light may be produced endogenously by the organism itself (symbiotic) or generated through a mut ...

s) scattered all over their undersides that create a sparkling glow. This provides counter-illumination

Counter-illumination is a method of active camouflage seen in marine animals such as firefly squid and midshipman fish, and in military prototypes, producing light to match their backgrounds in both brightness and wavelength.

Marine animals of ...

camouflage, preventing the animal from appearing as a dark shape when seen from below.

Some anglerfish

The anglerfish are ray-finned fish in the order Lophiiformes (). Both the order's common name, common and scientific name comes from the characteristic mode of predation, in which a modified dorsal Fish fin#Ray-fins, fin ray acts as a Aggressiv ...

of the deep sea, where it is too dark to hunt by sight, contain symbiotic

Symbiosis (Ancient Greek : living with, companionship < : together; and ''bíōsis'': living) is any type of a close and long-term biolo ...

bacteria in the 'bait' on their 'fishing rods'. These emit light to attract prey. Piper, Ross. ''Extraordinary Animals: An Encyclopedia of Curious and Unusual Animals''. Greenwood Press, 2007.

See also

*Albinism in biology

Albinism is the congenital absence of melanin in an animal or plant resulting in white hair, feathers, scales and skin and reddish pink or blue eyes. Individuals with the condition are referred to as albinos.

Varied use and interpretation of ...

* Chromatophore

Chromatophores are cells that produce color, of which many types are pigment-containing cells, or groups of cells, found in a wide range of animals including amphibians, fish, reptiles, crustaceans and cephalopod

A cephalopod is any member o ...

* Dog coat colours and patterns

* Cat coat genetics

Cat coat genetics determine the coloration, pattern, length, and texture of feline fur. The variations among cat coats are physical properties and should not be confused with cat breeds. A cat may display the coat of a certain breed without actu ...

* Deception in animals

Deception in animals is the voluntary or involuntary transmission of misinformation by one animal to another, of the same or different species, in a way that misleads the other animal. The psychology scholar Robert Mitchell identifies four level ...

* Equine coat colour

* Equine coat colour genetics

* Roan (colour)

* Fish coloration

References

Sources

* Cott, Hugh Bamford (1940). '' Adaptive Coloration in Animals''. Methuen, London. * Forbes, Peter (2009). '' Dazzled and Deceived: Mimicry and Camouflage''. Yale, New Haven and London.External links

Theme issue 'Animal coloration: production, perception, function and application'

(Royal Society)

* ttp://www.bioscience-explained.org/ENvol1_2/pdf/paletteEN.pdf Nature's Palette: How animals, including humans, produce colours {{Navboxes , title=Articles related to Animal coloration , list = {{vision in animals, state=expanded {{modelling ecosystems, expanded=none {{colour topics Zoology Evolution of animals Mimicry Warning coloration Camouflage