Alvis Octopus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Pseudastacus'' (meaning "false ''

Fossils of ''Pseudastacus'' had been described prior to the naming of this genus, under other names which are currently invalid. In 1839,

Fossils of ''Pseudastacus'' had been described prior to the naming of this genus, under other names which are currently invalid. In 1839,

* ''P. mucronatus'' was originally named as ''

* ''P. mucronatus'' was originally named as ''

''Pseudastacus'' is a small

''Pseudastacus'' is a small

Astacus

''Astacus'' (from the Greek , ', meaning "lobster" or "crayfish") is a genus of crayfish found in Europe and western Asia, comprising three extant (living) species and three extinct fossil species.

Due to the crayfish plague, crayfish of this ...

''", in comparison to the extant crayfish

Crayfish are freshwater crustaceans belonging to the clade Astacidea, which also contains lobsters. In some locations, they are also known as crawfish, craydids, crawdaddies, crawdads, freshwater lobsters, mountain lobsters, rock lobsters, ...

genus) is an extinct genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial n ...

of decapod crustaceans that lived during the Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a Geological period, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately Mya. The J ...

period in Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a subcontinent of Eurasia and it is located enti ...

, and possibly the Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 145 to 66 million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era, as well as the longest. At around 79 million years, it is the longest geological period of ...

period in Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to Lebanon–Syria border, the north and east and Israel to Blue ...

. Many species have been assigned to it, though the placement of some species remain uncertain and others have been reassigned to different genera. Fossils attributable to this genus were first described by Georg zu Münster Count Georg Ludwig Friedrich Wilhelm zu Münster (german: Georg Graf zu Münster; 17 February 1776 – 23 December 1844) was a German paleontologist.

Biography

Münster was born on 17 February 1776, in Langelage near Osnabrück. In 1800, he be ...

in 1839 under the name ''Bolina pustulosa'', but the generic name was changed in 1861 after Albert Oppel

Carl Albert Oppel (19 December 1831 – 23 December 1865) was a German paleontologist.

History

He was born at Hohenheim in Württemberg, on 19 December 1831. He first went to the University of Tübingen, where he graduated with a Ph.D. ...

noted that it was preoccupied

The Botanical and Zoological Codes of nomenclature treat the concept of synonymy differently.

* In botanical nomenclature, a synonym is a scientific name that applies to a taxon that (now) goes by a different scientific name. For example, Linn ...

. The genus has been placed into different families

Family (from la, familia) is a group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its members and of society. Idea ...

by numerous authors, historically being assigned to Nephropidae

Lobsters are a family (Nephropidae, synonym Homaridae) of marine crustaceans. They have long bodies with muscular tails and live in crevices or burrows on the sea floor. Three of their five pairs of legs have claws, including the first pair, ...

or Protastacidae. Currently, it is believed to be a member of Stenochiridae.

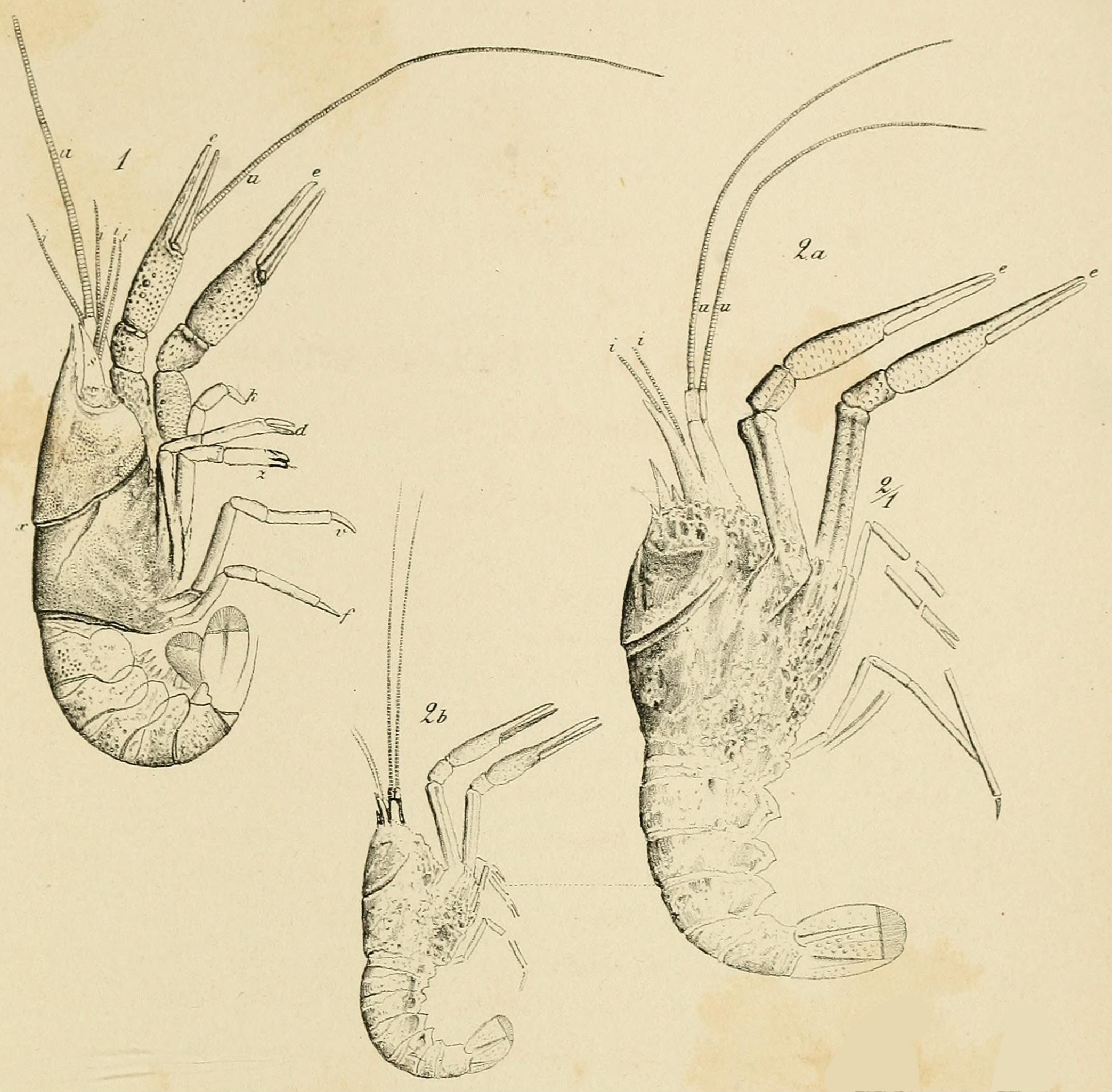

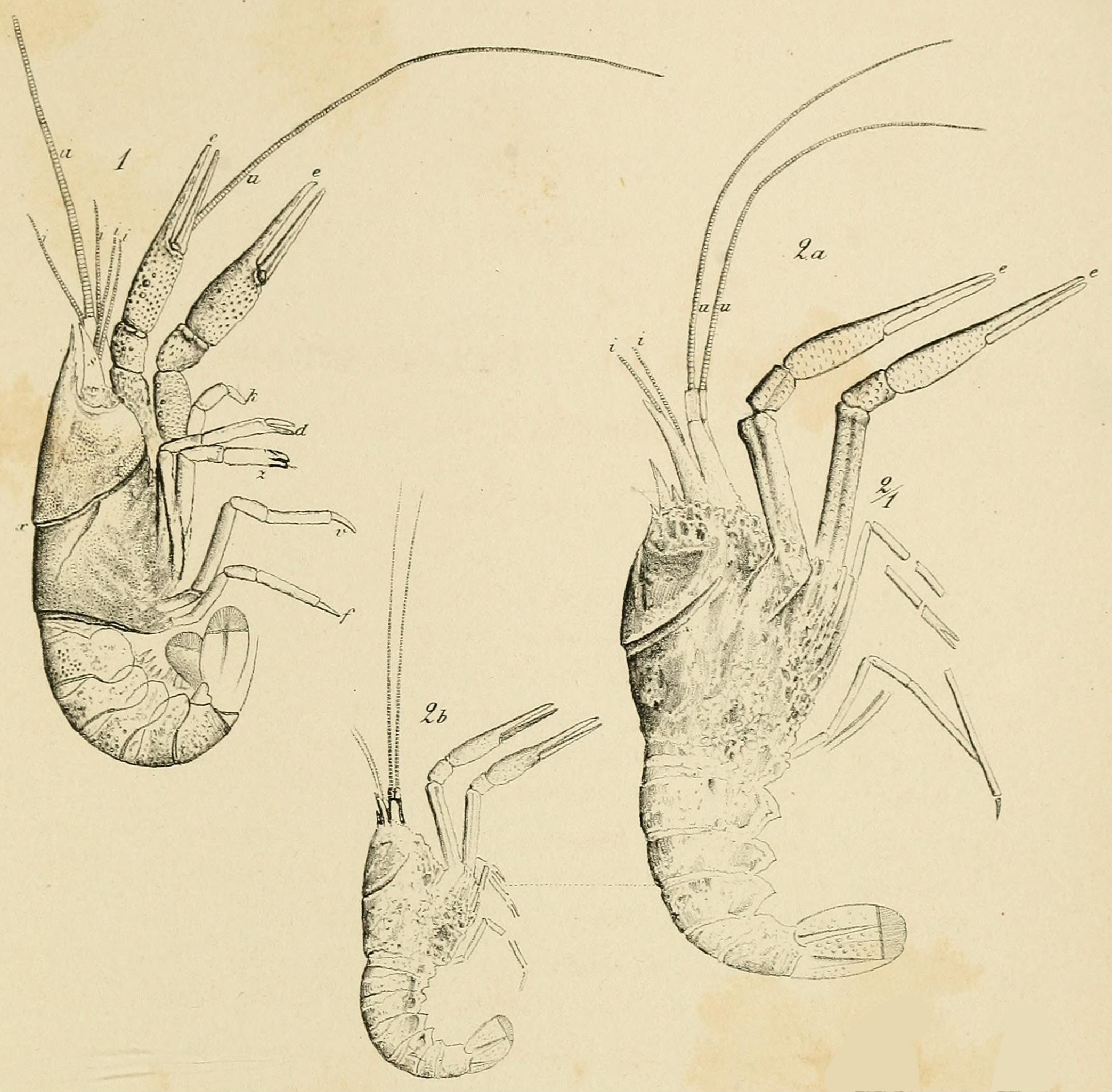

Not exceeding in total length, ''Pseudastacus'' was a small animal. Members of this genus have a crayfish-like build, possessing long antennae, a triangular rostrum

Rostrum may refer to:

* Any kind of a platform for a speaker:

**dais

**pulpit

* Rostrum (anatomy), a beak, or anatomical structure resembling a beak, as in the mouthparts of many sucking insects

* Rostrum (ship), a form of bow on naval ships

* Ros ...

and a frontmost pair of appendages enlarged into long and narrow pincers. Deep grooves are present on the carapace

A carapace is a dorsal (upper) section of the exoskeleton or shell in a number of animal groups, including arthropods, such as crustaceans and arachnids, as well as vertebrates, such as turtles and tortoises. In turtles and tortoises, the und ...

, which is around the same length as the abdomen

The abdomen (colloquially called the belly, tummy, midriff, tucky or stomach) is the part of the body between the thorax (chest) and pelvis, in humans and in other vertebrates. The abdomen is the front part of the abdominal segment of the tors ...

. The carapace is usually uneven, with either small tubercles

In anatomy, a tubercle (literally 'small tuber', Latin for 'lump') is any round nodule, small eminence, or warty outgrowth found on external or internal organs of a plant or an animal.

In plants

A tubercle is generally a wart-like projection, ...

or pits across the surface. Sexual dimorphism

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where the sexes of the same animal and/or plant species exhibit different morphological characteristics, particularly characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. The condition occurs in most an ...

is known in ''Pseudastacus'', with the pincers of the females being more elongated than those of the males. There is evidence of possible gregarious

Sociality is the degree to which individuals in an animal population tend to associate in social groups (gregariousness) and form cooperative societies.

Sociality is a survival response to evolutionary pressures. For example, when a mother w ...

behavior in the form of multiple individuals preserved alongside each other, possibly killed in a mass mortality event

A mass mortality event (MME) is a incident that kills a vast number of individuals of a single species in a short period of time. The event may put a species at risk of extinction or upset an ecosystem. This is distinct from the mass die-off ass ...

.

With the oldest known record dating to the Sinemurian

In the geologic timescale, the Sinemurian is an age and stage in the Early or Lower Jurassic Epoch or Series. It spans the time between 199.3 ± 2 Ma and 190.8 ± 1.5 Ma (million years ago). The Sinemurian is preceded by the Hettangian an ...

age of the early Jurassic

The Early Jurassic Epoch (in chronostratigraphy corresponding to the Lower Jurassic Series) is the earliest of three epochs of the Jurassic Period. The Early Jurassic starts immediately after the Triassic-Jurassic extinction event, 201.3 Ma ...

, and possible species surviving into the Cenomanian stage of the late Cretaceous

The Late Cretaceous (100.5–66 Ma) is the younger of two epochs into which the Cretaceous Period is divided in the geologic time scale. Rock strata from this epoch form the Upper Cretaceous Series. The Cretaceous is named after ''creta'', ...

, ''Pseudastacus'' has a long temporal range and was a widespread taxon. Fossils of this animal were first found in the Solnhofen Limestone of Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG),, is a country in Central Europe. It is the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany lies between the Baltic and North Sea to the north and the Alps to the sou ...

, but have also been recorded from France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan ar ...

, England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

and Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to Lebanon–Syria border, the north and east and Israel to Blue ...

. All species in this genus lived in marine environments

Marine habitats are habitats that support marine life. Marine life depends in some way on the saltwater that is in the sea (the term ''marine'' comes from the Latin ''mare'', meaning sea or ocean). A habitat is an ecological or environmental ...

.

Discovery and naming

Fossils of ''Pseudastacus'' had been described prior to the naming of this genus, under other names which are currently invalid. In 1839,

Fossils of ''Pseudastacus'' had been described prior to the naming of this genus, under other names which are currently invalid. In 1839, Georg zu Münster Count Georg Ludwig Friedrich Wilhelm zu Münster (german: Georg Graf zu Münster; 17 February 1776 – 23 December 1844) was a German paleontologist.

Biography

Münster was born on 17 February 1776, in Langelage near Osnabrück. In 1800, he be ...

established the genus ''Bolina'' to include two species, ''B. pustulosa'' (the type species

In zoological nomenclature, a type species (''species typica'') is the species name with which the name of a genus or subgenus is considered to be permanently taxonomically associated, i.e., the species that contains the biological type specimen( ...

) and ''B. angusta'', both of which are based on specimens collected from the Solnhofen Limestone. The generic name references the nymph Bolina In Greek mythology, Bolina (; Ancient Greek: Βολίνα) or Boline (Βολίνη) was a nymph. According to Pausanias, Bolina was once a mortal maiden of Achaea. She was loved by the god Apollo

Apollo, grc, Ἀπόλλωνος, Apóllōno ...

from Greek mythology

A major branch of classical mythology, Greek mythology is the body of myths originally told by the ancient Greeks, and a genre of Ancient Greek folklore. These stories concern the origin and nature of the world, the lives and activities of ...

. A year later, Münster described several fossils from the Solnhofen Limestone he believed to represent isopod

Isopoda is an order of crustaceans that includes woodlice and their relatives. Isopods live in the sea, in fresh water, or on land. All have rigid, segmented exoskeletons, two pairs of antennae, seven pairs of jointed limbs on the thorax, an ...

s, and erected the genus ''Alvis'' to contain the single species ''A. octopus'', naming it after the dwarf Alvíss

Alvíss (Old Norse: ; "All-Wise") was a dwarf in Norse mythology.

Thor's daughter, Þrúðr, was promised in marriage to Alvíss. Thor was unhappy with the match, however, so he devised a plan: Thor told Alvíss that, because of his small heigh ...

from Norse mythology

Norse, Nordic, or Scandinavian mythology is the body of myths belonging to the North Germanic peoples, stemming from Old Norse religion and continuing after the Christianization of Scandinavia, and into the Nordic folklore of the modern peri ...

.

In 1861, Albert Oppel

Carl Albert Oppel (19 December 1831 – 23 December 1865) was a German paleontologist.

History

He was born at Hohenheim in Württemberg, on 19 December 1831. He first went to the University of Tübingen, where he graduated with a Ph.D. ...

noted that the name ''Bolina'' was preoccupied

The Botanical and Zoological Codes of nomenclature treat the concept of synonymy differently.

* In botanical nomenclature, a synonym is a scientific name that applies to a taxon that (now) goes by a different scientific name. For example, Linn ...

by a genus of cnidaria

Cnidaria () is a phylum under kingdom Animalia containing over 11,000 species of aquatic animals found both in Fresh water, freshwater and Marine habitats, marine environments, predominantly the latter.

Their distinguishing feature is cnidocyt ...

n, and thus the crustacean named by Münster had to be renamed. Oppel placed ''B. pustulosa'' and ''B. angusta'' into two new genera, ''Pseudastacus'' and '' Stenochirus'' respectively. Now renamed as ''Pseudastacus pustulosus'' and ''Stenochirus angustus'', the two species became the type species of their own respective genera. The name ''Pseudastacus'' means "false ''Astacus

''Astacus'' (from the Greek , ', meaning "lobster" or "crayfish") is a genus of crayfish found in Europe and western Asia, comprising three extant (living) species and three extinct fossil species.

Due to the crayfish plague, crayfish of this ...

''", referencing its resemblance to the modern crayfish

Crayfish are freshwater crustaceans belonging to the clade Astacidea, which also contains lobsters. In some locations, they are also known as crawfish, craydids, crawdaddies, crawdads, freshwater lobsters, mountain lobsters, rock lobsters, ...

genus. Oppel declared that 10 specimens known at the time represented ''Pseudastacus pustulosus'', of which one was from the Redenbacher collection and the remaining nine were from the collection of the Palaeontological Museum, Munich

The Palaeontological Museum in Germany (''Paläontologisches Museum München''), is a German national natural history museum located in the city of Munich, Bavaria. It is associated with the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität. It has a large co ...

. In addition, he identified one specimen (BSPG AS I 672) housed in the Palaeontological Museum as a second species of the genus which he named ''Pseudastacus muensteri''. In 2006, Garassino and Schweigert reviewed the decapod fossils from Solnhofen and found that four of the ''P. pustulosus'' specimens from Oppel's collection were still present, and that ''P. muensteri'' is a junior synonym of ''P. pustulosus''.

Valid species

Several species have been assigned to the genus ''Pseudastacus'', though the placement of some species remains uncertain or tentative. In addition, some have since been moved into different genera after they were discovered not to be closely related to thetype species

In zoological nomenclature, a type species (''species typica'') is the species name with which the name of a genus or subgenus is considered to be permanently taxonomically associated, i.e., the species that contains the biological type specimen( ...

. In 2020, Charbonnier and Denis published a study including a summary of recognized stenochirid species, which covered the reclassification of former ''Pseudastacus'' species and left the following as members of the genus:

* ''P. pustulosus'' is the type species

In zoological nomenclature, a type species (''species typica'') is the species name with which the name of a genus or subgenus is considered to be permanently taxonomically associated, i.e., the species that contains the biological type specimen( ...

of the genus, first named as ''Bolina pustulosa'' by Münster in 1839 and moved to ''Pseudastacus'' in 1861. Its fossils were found in the Solnhofen Limestone of Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG),, is a country in Central Europe. It is the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany lies between the Baltic and North Sea to the north and the Alps to the sou ...

, which date back to the Tithonian

In the geological timescale, the Tithonian is the latest age of the Late Jurassic Epoch and the uppermost stage of the Upper Jurassic Series. It spans the time between 152.1 ± 4 Ma and 145.0 ± 4 Ma (million years ago). It is preceded by t ...

stage of the late Jurassic

The Late Jurassic is the third epoch of the Jurassic Period, and it spans the geologic time from 163.5 ± 1.0 to 145.0 ± 0.8 million years ago (Ma), which is preserved in Upper Jurassic strata.Owen 1987.

In European lithostratigraphy, the ...

period.

* ''P. mucronatus'' was originally named as ''

* ''P. mucronatus'' was originally named as ''Astacus

''Astacus'' (from the Greek , ', meaning "lobster" or "crayfish") is a genus of crayfish found in Europe and western Asia, comprising three extant (living) species and three extinct fossil species.

Due to the crayfish plague, crayfish of this ...

mucronatus'' by John Phillips in 1835. The type specimen was extracted from the Speeton Clay Formation

The Speeton Clay Formation (SpC)Speeton Clay Formation

- Yorkshire Yorkshire ( ; abbreviated Yorks), formally known as the County of York, is a historic county in northern England and by far the largest in the United Kingdom. Because of its large area in comparison with other English counties, functions have ...

, England, and is a fragment of the - Yorkshire Yorkshire ( ; abbreviated Yorks), formally known as the County of York, is a historic county in northern England and by far the largest in the United Kingdom. Because of its large area in comparison with other English counties, functions have ...

pincer Pincer may refer to:

*Pincers (tool)

*Pincer (biology), part of an animal

*Pincer ligand, a terdentate, often planar molecule that tightly binds a variety of metal ions

*The Pincer move in the game of Go

See also

*Pincer movement

The pincer ...

. The chela

Chela may refer to:

* ''Chela'' (fish), a genus of small minnow-type fish in the Cyprinid family

* Chela (organ), a pincer-like organ terminating certain limbs of some arthropods such as crabs

* Chela (meteorite), a meteorite fall of 1988 in Tanz ...

is very large, with alternating large and small tubercles on the inner margins. This is unlike the narrower and longer pincers of other ''Pseudastacus'' species, and the specimen may be referrable to '' Hoploparia dentata''.

* ''P. minor'' was described by Oscar Fraas

Oscar Friedrich von Fraas (17 January 1824, in Lorch (Württemberg) – 22 November 1897, in Stuttgart) was a German clergyman, paleontologist and geologist. He was the father of geologist Eberhard Fraas (1862–1915).

Biography

He studied theo ...

in 1878 from a specimen found in Cenomanian-aged deposits in Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to Lebanon–Syria border, the north and east and Israel to Blue ...

. This specimen is now lost and only the original illustration remains, which shows features unlike any other ''Pseudastacus'' species: the rostrum is extremely long, there is an additional abdomen segment, the clawed limbs are placed further back and the general pincer shape is different. Its placement in this genus is thus uncertain.

* ''P. pusillus'' is based on a fossil from the Bajocian

In the geologic timescale

The geologic time scale, or geological time scale, (GTS) is a representation of time based on the rock record of Earth. It is a system of chronological dating that uses chronostratigraphy (the process of relatin ...

-aged deposits of May-sur-Orne

May-sur-Orne (, literally ''May on Orne'') is a commune in the Calvados department in the Normandy region in northwestern France.

Population

See also

*Communes of the Calvados department

The following is a list of the 528 communes of the Ca ...

, France described in 1925 by Victor van Straelen

Victor van Straelen (14 June 1889 – 29 February 1964) was a Belgian conservationist, palaeontologist and carcinologist.

Van Straelen was born in Antwerp on 14 June 1889, and worked chiefly as a palaeontologist until his retirement in 1954.

H ...

. The fossil was destroyed in World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

and it is difficult to tell from the original line drawing of the specimen whether this species truly belongs to ''Pseudastacus''.

* ''P. lemovices'' was named in 2020 based on five specimens preserved in a slab of Sinemurian

In the geologic timescale, the Sinemurian is an age and stage in the Early or Lower Jurassic Epoch or Series. It spans the time between 199.3 ± 2 Ma and 190.8 ± 1.5 Ma (million years ago). The Sinemurian is preceded by the Hettangian an ...

-aged limestone

Limestone ( calcium carbonate ) is a type of carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of . Limestone forms wh ...

, collected from Chauffour-sur-Vell

Chauffour-sur-Vell is a commune in the Corrèze department

Department may refer to:

* Departmentalization, division of a larger organization into parts with specific responsibility

Government and military

*Department (administrative divisi ...

, France. The specific name honors the Lemovices

The Lemovīcēs (Gaulish: *''Lēmouīcēs'', 'those who vanquish by the elm') were a Gallic tribe dwelling in the modern Limousin region during the Iron Age and the Roman period.

Name

They are mentioned as ''Lemovices'' by Caesar (mid-1st c. ...

, a Gallic tribe that lived near this locality. It is the oldest known species of the family Stenochiridae.

Reassigned species

The following species were formerly placed in ''Pseudastacus'', but have now been moved to different genera. * ''P. hakelensis'' was first named as ''Homarus

''Homarus'' is a genus of lobsters, which include the common and commercially significant species ''Homarus americanus'' (the American lobster) and '' Homarus gammarus'' (the European lobster). The Cape lobster, which was formerly in this genu ...

hakelensis'' in 1878. The species lived during the Cenomanian stage in Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to Lebanon–Syria border, the north and east and Israel to Blue ...

. It was moved to ''Notahomarus

''Notahomarus'' is a genus of fossil lobster belonging to the family Nephropidae that is known from fossils found only in Lebanon. The type species, ''N. hakelensis'', was initially placed within the genus '' Homarus'' in 1878, but it was tr ...

'' in 2017.

* ''P. dubertreti'', described in 1946 from a fossil kept in the National Museum of Natural History, France

The French National Museum of Natural History, known in French as the ' (abbreviation MNHN), is the national natural history museum of France and a ' of higher education part of Sorbonne Universities. The main museum, with four galleries, is loca ...

, lived in Lebanon during the Cenomanian stage. Later study of the fossil found this species to be synonymous

A synonym is a word, morpheme, or phrase that means exactly or nearly the same as another word, morpheme, or phrase in a given language. For example, in the English language, the words ''begin'', ''start'', ''commence'', and ''initiate'' are all ...

with ''Carpopenaeus

''Carpopenaeus'' is an extinct genus of prawn, which existed during the Upper Jurassic and Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 145 to 66 million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the ...

callirostris'' in 2006.

* ''P. llopisi'' was named in 1971 and is known from numerous specimens found in the early Cretaceous

The Early Cretaceous (geochronological name) or the Lower Cretaceous ( chronostratigraphic name), is the earlier or lower of the two major divisions of the Cretaceous. It is usually considered to stretch from 145 Ma to 100.5 Ma.

Geology

Pr ...

-aged site of Las Hoyas, Spain. In 1997 it was reassigned to the genus ''Austropotamobius

''Austropotamobius'' is a genus of European crayfish in the family Astacidae. It contains four extant species, and one species known from fossils of Barremian age:

*''Austropotamobius bihariensis'' Pârvulescu 2019 — Idle crayfish

*''Austropota ...

''.

Description

''Pseudastacus'' is a small

''Pseudastacus'' is a small invertebrate

Invertebrates are a paraphyletic group of animals that neither possess nor develop a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''backbone'' or ''spine''), derived from the notochord. This is a grouping including all animals apart from the chordate ...

, with the carapace

A carapace is a dorsal (upper) section of the exoskeleton or shell in a number of animal groups, including arthropods, such as crustaceans and arachnids, as well as vertebrates, such as turtles and tortoises. In turtles and tortoises, the und ...

of ''P. lemovices'' reaching a length of (excluding the rostrum

Rostrum may refer to:

* Any kind of a platform for a speaker:

**dais

**pulpit

* Rostrum (anatomy), a beak, or anatomical structure resembling a beak, as in the mouthparts of many sucking insects

* Rostrum (ship), a form of bow on naval ships

* Ros ...

) and a height of . The known specimens of ''P. pustulosus'' range from in total length.

Members of this genus often have an uneven carapace surface, with some species (such as ''P. pustulosus'') having tubercle

In anatomy, a tubercle (literally 'small tuber', Latin for 'lump') is any round nodule, small eminence, or warty outgrowth found on external or internal organs of a plant or an animal.

In plants

A tubercle is generally a wart-like projection ...

s and others (such as ''P. lemovices'') having pits distributed uniformly across the carapace surface. Individuals with smoother carapaces are also documented, though this may be due to abrasion. Grooves are present on the carapace, including a deep, arch-shaped cervical groove that stretches across the top and sides of the carapace, and an additional groove behind it on either side. The rostrum is triangular and elongated, with three lateral spines. The carapace and head are separated by an arch-shaped incision. A pair of long antennae and two pairs of shorter antennule

Antennae ( antenna), sometimes referred to as "feelers", are paired appendages used for sensing in arthropods.

Antennae are connected to the first one or two segments of the arthropod head. They vary widely in form but are always made of one o ...

s extend from the head, with the outer antennules being slightly narrower and more pointed than the outer pair. A pair of compound eye

A compound eye is a visual organ found in arthropods such as insects and crustaceans. It may consist of thousands of ommatidia, which are tiny independent photoreception units that consist of a cornea, lens, and photoreceptor cells which dis ...

s are attached to the head by short eye stalks.

The first three pairs of appendages terminate with chelae

A chela ()also called a claw, nipper, or pinceris a pincer-like organ at the end of certain limbs of some arthropods. The name comes from Ancient Greek , through New Latin '. The plural form is chelae. Legs bearing a chela are called chelipeds. ...

(pincers), and the appendages furthest front are particularly long and enlarged. The abdomen

The abdomen (colloquially called the belly, tummy, midriff, tucky or stomach) is the part of the body between the thorax (chest) and pelvis, in humans and in other vertebrates. The abdomen is the front part of the abdominal segment of the tors ...

is around the length of the carapace, with the frontmost segment being the smallest. The pereiopod

The decapod (crustaceans such as a crab, lobster, shrimp or prawn) is made up of 20 body segments grouped into two main body parts: the cephalothorax and the pleon (abdomen). Each segment may possess one pair of appendages, although in various ...

s (walking legs) on the thorax decrease in size the further back they are placed, the pair furthest front being largest and longest. The uropod

Uropods are posterior appendages found on a wide variety of crustaceans. They typically have functions in locomotion.

Definition

Uropods are often defined as the appendages of the last body segment of a crustacean. An alternative definition sugge ...

s are equal in length, with a ridge down the middle and long seta

In biology, setae (singular seta ; from the Latin word for "bristle") are any of a number of different bristle- or hair-like structures on living organisms.

Animal setae

Protostomes

Annelid setae are stiff bristles present on the body. T ...

e on the margins.

Classification

In the centuries since it was first discovered, ''Pseudastacus'' has been placed in a wide variety offamilies

Family (from la, familia) is a group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its members and of society. Idea ...

by many different authors. For many decades, the genus was thought to be a member of Nephropidae

Lobsters are a family (Nephropidae, synonym Homaridae) of marine crustaceans. They have long bodies with muscular tails and live in crevices or burrows on the sea floor. Three of their five pairs of legs have claws, including the first pair, ...

(the lobster family), as first reported by Victor van Straelen

Victor van Straelen (14 June 1889 – 29 February 1964) was a Belgian conservationist, palaeontologist and carcinologist.

Van Straelen was born in Antwerp on 14 June 1889, and worked chiefly as a palaeontologist until his retirement in 1954.

H ...

in 1925. This placement was followed by subsequent authors such as Beurlen (1928), Glaessner (1929), and Chong & Förster (1976). In 1983, Henning Albrecht

Henning Albrecht (born 1973) is a German historian.

Life

From 2003 to 2006, Albrecht was a research assistant at of the University of Hamburg and was awarded his doctorate there in 2007 with his dissertation ''Antiliberalismus und Antisemitis ...

erected the family Protastacidae and moved ''Pseudastacus'' into it, whereas Tshudy & Babcock (1997) included the genus into their newly-established family Chilenophoberidae. Although Garassino & Schweigert (2006) continued to place ''Pseudastacus'' in Proastacidae following Albrecht (1983), other authors in the 2000s would place it in Chilenophoberidae based on the more recent findings of Tshudy & Babcock (1997).

In 2013, Karasawa ''et al.'' recovered ''Pseudastacus'' as the sister taxon

In phylogenetics, a sister group or sister taxon, also called an adelphotaxon, comprises the closest relative(s) of another given unit in an evolutionary tree.

Definition

The expression is most easily illustrated by a cladogram:

Taxon A and ...

to '' Stenochirus'', making Chilenophoberidae a paraphyletic

In taxonomy (general), taxonomy, a group is paraphyletic if it consists of the group's most recent common ancestor, last common ancestor and most of its descendants, excluding a few Monophyly, monophyletic subgroups. The group is said to be pa ...

group. The family was therefore synonymized with Stenochiridae. The following cladogram shows the placement of ''Pseudastacus'' within Stenochiridae according to the study:

Palaeobiology

Sexual dimorphism

Albert Oppel

Carl Albert Oppel (19 December 1831 – 23 December 1865) was a German paleontologist.

History

He was born at Hohenheim in Württemberg, on 19 December 1831. He first went to the University of Tübingen, where he graduated with a Ph.D. ...

noticed that ''Pseudastacus'' fossils from the Solnhofen Limestone could be distinguished into two morphs; aside from those most similar to the ''P. pustulosus'' type specimen

In biology, a type is a particular specimen (or in some cases a group of specimens) of an organism to which the scientific name of that organism is formally attached. In other words, a type is an example that serves to anchor or centralizes the ...

, there were also some with smaller bodies and longer, more slender claws. Oppel believed the latter morph to be a separate species which in 1862 he named ''P. muensteri''. Over a century later, Garassino and Guenter (2006) found that specimens of ''P. muensteri'' were essentially identical to ''P. pustulosus'' aside from the claw form. In addition, they noted that in fossil glypheids and the extant ''Neoglyphea inopinata

''Neoglyphea inopinata'' is a species of glypheoid lobster, a group thought long extinct before ''Neoglyphea'' was discovered. It is a lobster-like animal, up to around in length, although without claws. It is only known from 17 specimens, cau ...

'', the females possess longer clawed limbs than the males. Based on this, they declared ''P. muensteri'' as a junior synonym of ''P. pustulosus'', actually representing female specimens of the species.

Social behavior

Thetype series

In biology, a type is a particular specimen (or in some cases a group of specimens) of an organism to which the scientific name of that organism is formally attached. In other words, a type is an example that serves to anchor or centralizes the ...

of ''P. lemovices'' is made up of five individuals preserved together in a single limestone

Limestone ( calcium carbonate ) is a type of carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of . Limestone forms wh ...

slab, possibly indicating the species exhibited gregarious

Sociality is the degree to which individuals in an animal population tend to associate in social groups (gregariousness) and form cooperative societies.

Sociality is a survival response to evolutionary pressures. For example, when a mother w ...

behaviour, with this group being killed in a mass mortality event

A mass mortality event (MME) is a incident that kills a vast number of individuals of a single species in a short period of time. The event may put a species at risk of extinction or upset an ecosystem. This is distinct from the mass die-off ass ...

(perhaps caused by temperature changes or lack of oxygen). Evidence of gregarious behaviour is also known in other fossil lobsters, as well as in extant species.

Palaeoenvironment

Early Jurassic

''Pseudastacus'' is believed to have first evolved during theearly Jurassic

The Early Jurassic Epoch (in chronostratigraphy corresponding to the Lower Jurassic Series) is the earliest of three epochs of the Jurassic Period. The Early Jurassic starts immediately after the Triassic-Jurassic extinction event, 201.3 Ma ...

, with ''P. lemovices'' being the oldest member of the genus currently known. The five known specimens of this species were preserved in a single limestone slab collected from a garden in Chauffour-sur-Vell

Chauffour-sur-Vell is a commune in the Corrèze department

Department may refer to:

* Departmentalization, division of a larger organization into parts with specific responsibility

Government and military

*Department (administrative divisi ...

, France. This sediment in this locality represents a marine environment

Marine habitats are habitats that support marine life. Marine life depends in some way on the saltwater that is in the sea (the term ''marine'' comes from the Latin ''mare'', meaning sea or ocean). A habitat is an ecological or environmen ...

dating back to the Sinemurian

In the geologic timescale, the Sinemurian is an age and stage in the Early or Lower Jurassic Epoch or Series. It spans the time between 199.3 ± 2 Ma and 190.8 ± 1.5 Ma (million years ago). The Sinemurian is preceded by the Hettangian an ...

age, and the general area has been specifically dated to the late Sinemurian based on the presence of the green alga

The green algae (singular: green alga) are a group consisting of the Prasinodermophyta and its unnamed sister which contains the Chlorophyta and Charophyta/ Streptophyta. The land plants ( Embryophytes) have emerged deep in the Charophyte alg ...

''Palaeodasycladus mediterraneus'' in a regional bed.

Late Jurassic

''Pseudastacus pustulosus'', the type species of the genus, is also known from the most specimens. All known remains of this species were collected from the Solnhofen Limestone ofBavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total l ...

, Germany, which dates to the Tithonian

In the geological timescale, the Tithonian is the latest age of the Late Jurassic Epoch and the uppermost stage of the Upper Jurassic Series. It spans the time between 152.1 ± 4 Ma and 145.0 ± 4 Ma (million years ago). It is preceded by t ...

age of the late Jurassic

The Late Jurassic is the third epoch of the Jurassic Period, and it spans the geologic time from 163.5 ± 1.0 to 145.0 ± 0.8 million years ago (Ma), which is preserved in Upper Jurassic strata.Owen 1987.

In European lithostratigraphy, the ...

period. During the time of deposition, the European continent was partly inundated, forming a dry, tropical archipelago

An archipelago ( ), sometimes called an island group or island chain, is a chain, cluster, or collection of islands, or sometimes a sea containing a small number of scattered islands.

Examples of archipelagos include: the Indonesian Archi ...

at the edge of the Tethys Ocean

The Tethys Ocean ( el, Τηθύς ''Tēthús''), also called the Tethys Sea or the Neo-Tethys, was a prehistoric ocean that covered most of the Earth during much of the Mesozoic Era and early Cenozoic Era, located between the ancient continents ...

. The Solnhofen Limestone would have been laid down in a lagoon

A lagoon is a shallow body of water separated from a larger body of water by a narrow landform, such as reefs, barrier islands, barrier peninsulas, or isthmuses. Lagoons are commonly divided into '' coastal lagoons'' (or ''barrier lagoons' ...

al environment cut off from the main ocean by reefs. A coastal habitat is further confirmed by the fossil content of the area, which includes numerous marine species that ''P. pustulosus'' would have lived alongside. These include cephalopods (such as ammonoid

Ammonoids are a group of extinct marine mollusc animals in the subclass Ammonoidea of the class Cephalopoda. These molluscs, commonly referred to as ammonites, are more closely related to living coleoids (i.e., octopuses, squid and cuttlefi ...

s and belemnite

Belemnitida (or the belemnite) is an extinct order of squid-like cephalopods that existed from the Late Triassic to Late Cretaceous. Unlike squid, belemnites had an internal skeleton that made up the cone. The parts are, from the arms-most to ...

s), crinoids (such as '' Saccocoma''), other crustaceans (including eryonids, axiids, glypheids, mantis shrimp

Mantis shrimp, or stomatopods, are carnivorous marine crustaceans of the order Stomatopoda (). Stomatopods branched off from other members of the class Malacostraca around 340 million years ago. Mantis shrimp typically grow to around in length ...

s, and the closely related '' Stenochirus''), fish (such as pycnodonts

Pycnodontiformes is an extinct order of primarily marine bony fish. The group first appeared during the Late Triassic and disappeared during the Eocene. The group has been found in rock formations in Africa, Asia, Europe, North and South Ameri ...

, pachycormids

Pachycormiformes is an extinct order of marine ray-finned fish known from the Early Jurassic to the end of the Cretaceous. It only includes a single family, Pachycormidae. They were characterized by having serrated pectoral fins (though more ...

, aspidorhynchids and caturids

Caturidae is an extinct family of fishes belonging to the order Amiiformes (which contains the modern bowfin) which ranges from the Jurassic (possibly Triassic) to Cretaceous. Members of the family include ''Caturus

''Caturus'' (from el, ...

) and marine reptiles (such as turtle

Turtles are an order of reptiles known as Testudines, characterized by a special shell developed mainly from their ribs. Modern turtles are divided into two major groups, the Pleurodira (side necked turtles) and Cryptodira (hidden necked ...

s, ichthyosaur

Ichthyosaurs (Ancient Greek for "fish lizard" – and ) are large extinct marine reptiles. Ichthyosaurs belong to the order known as Ichthyosauria or Ichthyopterygia ('fish flippers' – a designation introduced by Sir Richard Owen in 1842, altho ...

s and metriorhynchid

Metriorhynchidae is an extinct family of specialized, aquatic metriorhynchoid crocodyliforms from the Middle Jurassic to the Early Cretaceous period (Bajocian to early Aptian) of Europe, North America and South America. The name Metriorhynchi ...

s). Remains of terrestrial animals, though rarer, are also present and represent species that would have lived on the islands surrounded by the lagoons, including dinosaurs (such as ''Archaeopteryx

''Archaeopteryx'' (; ), sometimes referred to by its German name, "" ( ''Primeval Bird''), is a genus of bird-like dinosaurs. The name derives from the ancient Greek (''archaīos''), meaning "ancient", and (''ptéryx''), meaning "feather" ...

'' and ''Compsognathus

''Compsognathus'' (; Greek ''kompsos''/κομψός; "elegant", "refined" or "dainty", and ''gnathos''/γνάθος; "jaw") is a genus of small, bipedal, carnivorous theropod dinosaur. Members of its single species ''Compsognathus longipes'' ...

''), lizards (such as ''Ardeosaurus

''Ardeosaurus'' is an extinct genus of basal lizards, known from fossils found in the Late Jurassic Solnhofen Plattenkalk of Bavaria, southern Germany. It was originally thought to have been a species of ''Homeosaurus''.

''Ardeosaurus'' was ...

'', ''Bavarisaurus

''Bavarisaurus'' ('Bavarian lizard') is an extinct genus of basal squamate found in the Solnhofen limestone near Bavaria, Germany.Schoenesmahl''), and

pterosaur

Pterosaurs (; from Greek ''pteron'' and ''sauros'', meaning "wing lizard") is an extinct clade of flying reptiles in the Order (biology), order, Pterosauria. They existed during most of the Mesozoic: from the Late Triassic to the end of the Cre ...

s.

Cretaceous

Two ''Pseudastacus'' species, ''P. mucronatus'' and ''P. minor'', originate from deposits dating to theCretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 145 to 66 million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era, as well as the longest. At around 79 million years, it is the longest geological period of ...

period, though their assignment to this genus remains uncertain. These two species did not coexist, being from different stages of the Cretaceous as well as different locations. Known remains of ''P. mucronatus'' have been collected from the Speeton Clay Formation

The Speeton Clay Formation (SpC)Speeton Clay Formation

- England England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

, which extends from the - England England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

Berriasian

In the geological timescale, the Berriasian is an age/ stage of the Early/Lower Cretaceous. It is the oldest subdivision in the entire Cretaceous. It has been taken to span the time between 145.0 ± 4.0 Ma and 139.8 ± 3.0 Ma (million years a ...

to Aptian

The Aptian is an age in the geologic timescale or a stage in the stratigraphic column. It is a subdivision of the Early or Lower Cretaceous Epoch or Series and encompasses the time from 121.4 ± 1.0 Ma to 113.0 ± 1.0 Ma (million years ag ...

ages of the early Cretaceous

The Early Cretaceous (geochronological name) or the Lower Cretaceous ( chronostratigraphic name), is the earlier or lower of the two major divisions of the Cretaceous. It is usually considered to stretch from 145 Ma to 100.5 Ma.

Geology

Pr ...

. The formation was a marine environment that initially was deposited during a period of marine transgression

A marine transgression is a geologic event during which sea level rises relative to the land and the shoreline moves toward higher ground, which results in flooding. Transgressions can be caused by the land sinking or by the ocean basins filling ...

, which later transitioned into an event of marine regression

A marine regression is a geological process occurring when areas of submerged seafloor are exposed above the sea level. The opposite event, marine transgression, occurs when flooding from the sea covers previously-exposed land.

Evidence of marin ...

, correlating to sequences of warmer and cooler temperatures. This is reflected in the formation's interbedded layers of mudstones and clay

Clay is a type of fine-grained natural soil material containing clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g. kaolin, Al2 Si2 O5( OH)4).

Clays develop plasticity when wet, due to a molecular film of water surrounding the clay part ...

s. The Speeton Clay Formation preserves fossilized remains of various marine animals, with those of belemnites being the most abundant. Ammonite

Ammonoids are a group of extinct marine mollusc animals in the subclass Ammonoidea of the class Cephalopoda. These molluscs, commonly referred to as ammonites, are more closely related to living coleoids (i.e., octopuses, squid and cuttle ...

s, crustacean

Crustaceans (Crustacea, ) form a large, diverse arthropod taxon which includes such animals as decapods, seed shrimp, branchiopods, fish lice, krill, remipedes, isopods, barnacles, copepods, amphipods and mantis shrimp. The crustacean gro ...

s, and the teeth of sharks and rays (including ''Cretorectolobus

''Cretorectolobus'' is an extinct carpet shark. It was described by G.R. Case in 1978, and the type species is ''C. olsoni'', which existed during the Campanian in Canada and the United States. Another species, ''C. gracilis'', was described by C ...

'', '' Spathobatis'', ''Dasyatis

''Dasyatis'' (Greek δασύς ''dasýs'' meaning rough or dense and βατίς ''batís'' meaning skate) is a genus of stingray in the family Dasyatidae that is native to the Atlantic, including the Mediterranean. In a 2016 taxonomic revisi ...

'' and ''Synechodus

''Palaeospinax'' is an extinct genus of shark which lived from the Early Triassic to the end of the Eocene epoch. Although several species have been described, the genus is considered ''nomen dubium'' because the type-specimen of the type species ...

'') are also commonly recorded from these deposits.

Known from a single (currently missing) specimen from the Cenomanian-aged marine deposits of Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to Lebanon–Syria border, the north and east and Israel to Blue ...

, ''P. minor'' would be the geologically youngest species of ''Pseudastacus'', assuming it does belong to the genus. During this age, Lebanon was located on a large carbonate platform

A carbonate platform is a sedimentary body which possesses topographic relief, and is composed of autochthonic calcareous deposits. Platform growth is mediated by sessile organisms whose skeletons build up the reef or by organisms (usually mic ...

mostly submerged in the Neotethys Ocean

The Tethys Ocean ( el, Τηθύς ''Tēthús''), also called the Tethys Sea or the Neo-Tethys, was a prehistoric ocean that covered most of the Earth during much of the Mesozoic Era and early Cenozoic Era, located between the ancient continents ...

, and located near the northeastern edge of the Afro-Arabian continent. Plant fossils from Cenomanian Lebanese deposits (including gymnosperms and deciduous

In the fields of horticulture and Botany, the term ''deciduous'' () means "falling off at maturity" and "tending to fall off", in reference to trees and shrubs that seasonally shed leaves, usually in the autumn; to the shedding of petals, a ...

angiosperms

Flowering plants are plants that bear flowers and fruits, and form the clade Angiospermae (), commonly called angiosperms. They include all forbs (flowering plants without a woody stem), grasses and grass-like plants, a vast majority of br ...

) indicate a similar climate to the modern-day Mediterranean Basin

In biogeography, the Mediterranean Basin (; also known as the Mediterranean Region or sometimes Mediterranea) is the region of lands around the Mediterranean Sea that have mostly a Mediterranean climate, with mild to cool, rainy winters and w ...

, and are similar to floral assemblages from contemporary Crimea

Crimea, crh, Къырым, Qırım, grc, Κιμμερία / Ταυρική, translit=Kimmería / Taurikḗ ( ) is a peninsula in Ukraine, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, that has been occupied by Russia since 2014. It has a p ...

, North America and Central Europe. The paleontological sites of Lebanon have yielded many well-preserved fossils, including a wide variety of fish, crustaceans and even octopus

An octopus ( : octopuses or octopodes, see below for variants) is a soft-bodied, eight- limbed mollusc of the order Octopoda (, ). The order consists of some 300 species and is grouped within the class Cephalopoda with squids, cuttlefis ...

es. Terrestrial insects and reptiles (including pterosaur

Pterosaurs (; from Greek ''pteron'' and ''sauros'', meaning "wing lizard") is an extinct clade of flying reptiles in the Order (biology), order, Pterosauria. They existed during most of the Mesozoic: from the Late Triassic to the end of the Cre ...

s and squamates

Squamata (, Latin ''squamatus'', 'scaly, having scales') is the largest order of reptiles, comprising lizards, snakes, and amphisbaenians (worm lizards), which are collectively known as squamates or scaled reptiles. With over 10,900 species, it ...

) are also represented in the fossil finds from these deposits.

References

External links

* {{taxonbar, from1=Q3924858 Jurassic crustaceans Solnhofen fauna Fossil taxa described in 1861