Alfred Nobel on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

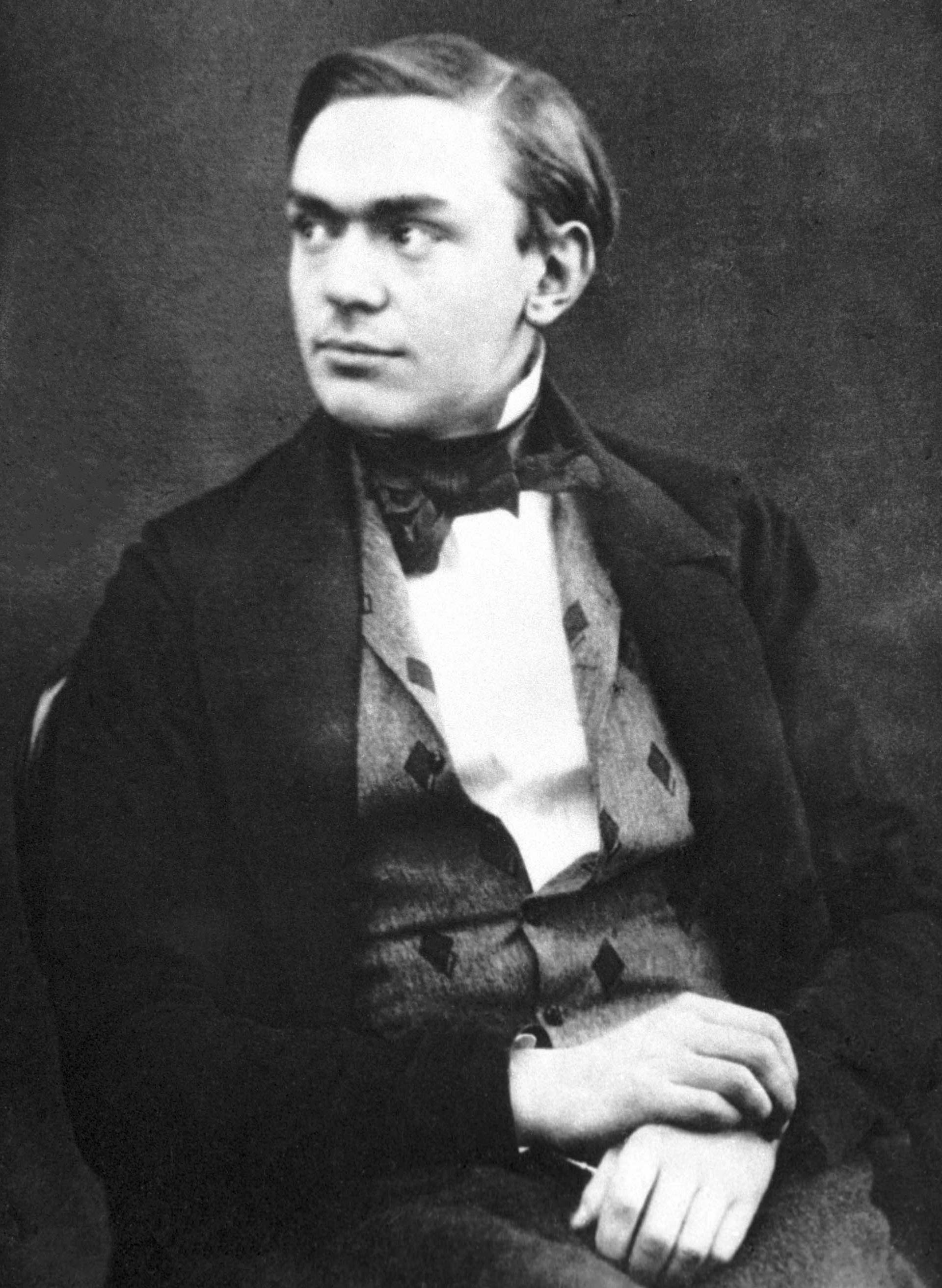

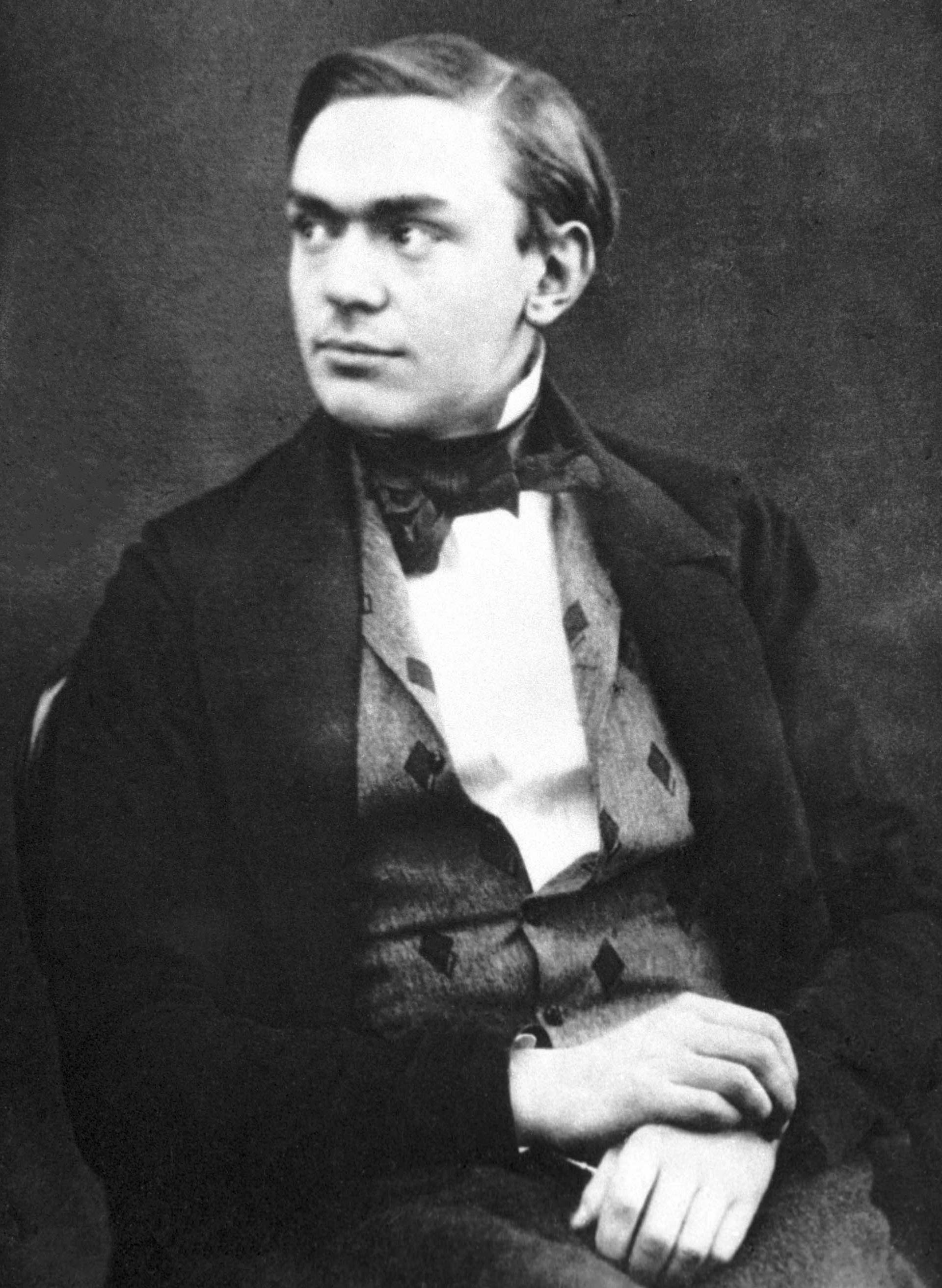

Alfred Bernhard Nobel ( ; ; 21 October 1833 – 10 December 1896) was a Swedish

Following various business failures caused by the loss of some barges of building material, Immanuel Nobel was forced into bankruptcy, Nobel's father moved to

Following various business failures caused by the loss of some barges of building material, Immanuel Nobel was forced into bankruptcy, Nobel's father moved to

As a young man, Nobel studied with chemist Nikolai Zinin; then, in 1850, went to Paris to further the work. There he met

As a young man, Nobel studied with chemist Nikolai Zinin; then, in 1850, went to Paris to further the work. There he met

"The Nobels in Baku"

in ''Azerbaijan International'', Vol 10.2, 56–59. * Evlanoff, M. and Fluor, M. ''Alfred Nobel – The Loneliest Millionaire''. Los Angeles, Ward Ritchie Press, 1969. * * Schück, H, and Sohlman, R., (1929). ''The Life of Alfred Nobel'', transl.

The Man Behind the Prize – Alfred Nobel

(mostly in Russian) * * * ttps://www.researchgate.net/publication/338139787_Alfred_Nobel_and_his_unknown_coworker Alfred Nobel and his unknown coworker {{DEFAULTSORT:Nobel, Alfred 1833 births 1896 deaths 19th-century Swedish businesspeople 19th-century Swedish chemists 19th-century Swedish engineers 19th-century Swedish philanthropists 19th-century Swedish scientists Bofors people Burials at Norra begravningsplatsen Engineers from Stockholm Explosives engineers Members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

chemist

A chemist (from Greek ''chēm(ía)'' alchemy; replacing ''chymist'' from Medieval Latin ''alchemist'') is a graduated scientist trained in the study of chemistry, or an officially enrolled student in the field. Chemists study the composition of ...

, inventor, engineer, and businessman. He is known for inventing dynamite

Dynamite is an explosive made of nitroglycerin, sorbents (such as powdered shells or clay), and Stabilizer (chemistry), stabilizers. It was invented by the Swedish people, Swedish chemist and engineer Alfred Nobel in Geesthacht, Northern German ...

, as well as having bequeathed his fortune to establish the Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; ; ) are awards administered by the Nobel Foundation and granted in accordance with the principle of "for the greatest benefit to humankind". The prizes were first awarded in 1901, marking the fifth anniversary of Alfred N ...

s. He also made several other important contributions to science, holding 355 patent

A patent is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the legal right to exclude others from making, using, or selling an invention for a limited period of time in exchange for publishing an sufficiency of disclosure, enabling discl ...

s during his life.

Born into the prominent Nobel family

The Nobel family ( ), is a prominent Swedish family closely related to the history both of Sweden and of Russia in the 19th and 20th centuries. Its legacy includes its outstanding contributions to philanthropy and to the development of the ar ...

in Stockholm, Nobel displayed an early aptitude for science and learning, particularly in chemistry and languages; he became fluent in six languages and filed his first patent at the age of 24. He embarked on many business ventures with his family, most notably owning the company Bofors

AB Bofors ( , , ) is a former Swedish arms manufacturer which today is part of the British arms manufacturer BAE Systems. The name has been associated with the iron industry and artillery manufacturing for more than 350 years.

History

Locate ...

, which was an iron and steel producer that he had developed into a major manufacturer of cannons and other armaments. Nobel's most famous invention, dynamite, was an explosive made using nitroglycerin

Nitroglycerin (NG) (alternative spelling nitroglycerine), also known as trinitroglycerol (TNG), nitro, glyceryl trinitrate (GTN), or 1,2,3-trinitroxypropane, is a dense, colorless or pale yellow, oily, explosive liquid most commonly produced by ...

, which was patented in 1867. He further invented gelignite

Gelignite (), also known as blasting gelatin or simply "jelly", is an explosive material consisting of collodion-cotton (a type of nitrocellulose or guncotton) dissolved in either nitroglycerine or nitroglycol and mixed with wood pulp and Potassi ...

in 1875 and ballistite

Ballistite is a smokeless propellant made from two high explosives, nitrocellulose and nitroglycerine. It was developed and patented by Alfred Nobel in the late 19th century.

Military adoption

Alfred Nobel patented Ballistite in 1887 while li ...

in 1887.

Upon his death, Nobel donated his fortune to a foundation to fund the Nobel Prizes, which annually recognize those who "conferred the greatest benefit to humankind". The synthetic element nobelium

Nobelium is a synthetic element, synthetic chemical element; it has Chemical symbol, symbol No and atomic number 102. It is named after Alfred Nobel, the inventor of dynamite and benefactor of science. A radioactive metal, it is the tenth transura ...

was named after him, and his name and legacy also survive in companies such as Dynamit Nobel

Dynamit Nobel AG is a German chemical and weapons company whose headquarters is in Troisdorf, Germany. It was founded in 1865 by Alfred Nobel.

Creation

After the death of his younger brother Emil Oskar Nobel, Emil in an 1864 nitroglycerin expl ...

and AkzoNobel

Akzo Nobel N.V., stylised as AkzoNobel, is a Dutch multinational corporation, multinational company which creates paints and performance coatings for both industry and consumers worldwide. Headquartered in Amsterdam, the company has activities ...

, which descend from mergers with companies he founded. Nobel was elected a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences () is one of the Swedish Royal Academies, royal academies of Sweden. Founded on 2 June 1739, it is an independent, non-governmental scientific organization that takes special responsibility for promoting nat ...

, which, pursuant to his will, is responsible for choosing the Nobel laureates

The Nobel Prizes (, ) are awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, the Swedish Academy, the Karolinska Institutet, and the Norwegian Nobel Committee to individuals and organizations who make outstanding contributions in th ...

in Physics

Physics is the scientific study of matter, its Elementary particle, fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge whi ...

and in Chemistry

Chemistry is the scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a physical science within the natural sciences that studies the chemical elements that make up matter and chemical compound, compounds made of atoms, molecules a ...

.

Biography

Early life and education

Alfred Nobel was born in Stockholm,Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. It borders Norway to the west and north, and Finland to the east. At , Sweden is the largest Nordic count ...

, on 21 October 1833. He was the third son of Immanuel Nobel

Immanuel Nobel the Younger ( , ; 24 March 1801 – 3 September 1872) was a Swedish people, Swedish engineer, architect, inventor and industrialist. He was the inventor of the Lathe (tool), rotary lathe used in plywood manufacturing. He was a mem ...

(1801–1872), an inventor and engineer, and Andriette Nobel

Karolina Andriette Nobel (born Karolina Andriette Ahlsell; 30 September 1803 – 7 December 1889) was a Swedish woman and the mother of scientist Alfred Nobel. Andriette was the daughter of Carolina Roospigg, and her father worked as a head clerk ...

(née

The birth name is the name of the person given upon their birth. The term may be applied to the surname, the given name or to the entire name. Where births are required to be officially registered, the entire name entered onto a births registe ...

Ahlsell 1805–1889). The couple married in 1827 and had eight children. The family was impoverished and only Alfred and his three brothers survived beyond their childhood. Through his father, Alfred Nobel was a descendant of the Swedish scientist Olaus Rudbeck

Olaus Rudbeck (also known as Olof Rudbeck the Elder, to distinguish him from his son, and occasionally with the surname Latinized as ''Olaus Rudbeckius'') (13 September 1630 – 12 December 1702) was a Swedish scientist and writer, professor ...

(1630–1702). Nobel's father was an alumnus of Royal Institute of Technology

KTH Royal Institute of Technology (), abbreviated KTH, is a public research university in Stockholm, Sweden. KTH conducts research and education in engineering and technology and is Sweden's largest technical university. Since 2018, KTH consist ...

in Stockholm and was an engineer and inventor who built bridges and buildings and experimented with different ways of blasting rocks. He encouraged and taught Nobel from a young age.

Following various business failures caused by the loss of some barges of building material, Immanuel Nobel was forced into bankruptcy, Nobel's father moved to

Following various business failures caused by the loss of some barges of building material, Immanuel Nobel was forced into bankruptcy, Nobel's father moved to Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the List of cities and towns in Russia by population, second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the Neva, River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland ...

, then part of the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

, and grew successful there as a manufacturer of machine tools and explosives. He invented the veneer lathe

A lathe () is a machine tool that rotates a workpiece about an axis of rotation to perform various operations such as cutting, sanding, knurling, drilling, deformation, facing, threading and turning, with tools that are applied to the w ...

, which made possible the production of modern plywood

Plywood is a composite material manufactured from thin layers, or "plies", of wood veneer that have been stacked and glued together. It is an engineered wood from the family of manufactured boards, which include plywood, medium-density fibreboa ...

, and started work on the naval mine

A naval mine is a self-contained explosive weapon placed in water to damage or destroy surface ships or submarines. Similar to anti-personnel mine, anti-personnel and other land mines, and unlike purpose launched naval depth charges, they are ...

. In 1842, the family joined him in the city. Now prosperous, his parents were able to send Nobel to private tutors, and the boy excelled in his studies, particularly in chemistry and languages, achieving fluency in English, French

French may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France

** French people, a nation and ethnic group

** French cuisine, cooking traditions and practices

Arts and media

* The French (band), ...

, German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany, the country of the Germans and German things

**Germania (Roman era)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizenship in Germany, see also Ge ...

, and Russian

Russian(s) may refer to:

*Russians (), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*A citizen of Russia

*Russian language, the most widely spoken of the Slavic languages

*''The Russians'', a b ...

. For 18 months, from 1841 to 1842, Nobel attended the Jacobs Apologistic School in Stockholm, his only schooling; he never attended university.

Nobel gained proficiency in Swedish, French, Russian, English, German, and Italian. He also developed sufficient literary skill to write poetry

Poetry (from the Greek language, Greek word ''poiesis'', "making") is a form of literature, literary art that uses aesthetics, aesthetic and often rhythmic qualities of language to evoke meaning (linguistics), meanings in addition to, or in ...

in English. His ''Nemesis

In ancient Greek religion and myth, Nemesis (; ) also called Rhamnousia (or Rhamnusia; ), was the goddess who personified retribution for the sin of hubris: arrogance before the gods.

Etymology

The name ''Nemesis'' is derived from the Greek ...

'' is a prose tragedy in four acts about the Italian noblewoman Beatrice Cenci

Beatrice Cenci ( , ; 6 February 157711 September 1599) was an Italian noblewoman imprisoned and repeatedly raped by her own father. She killed him, and was tried for murder. Despite outpourings of public sympathy, Cenci was beheaded in 1599 ...

. It was printed while he was dying, but the entire stock was destroyed immediately after his death except for three copies, being regarded as scandalous and blasphemous

Blasphemy refers to an insult that shows contempt, disrespect or lack of Reverence (emotion), reverence concerning a deity, an object considered sacred, or something considered Sanctity of life, inviolable. Some religions, especially Abrahamic o ...

. It was published in Sweden in 2003 and has been translated into Slovenian, French, Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, a Romance ethnic group related to or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance languag ...

, and Spanish.

Scientific career

As a young man, Nobel studied with chemist Nikolai Zinin; then, in 1850, went to Paris to further the work. There he met

As a young man, Nobel studied with chemist Nikolai Zinin; then, in 1850, went to Paris to further the work. There he met Ascanio Sobrero

Ascanio Sobrero (12 October 1812 – 26 May 1888) was an Italian chemist, born in Casale Monferrato. He studied under Théophile-Jules Pelouze at the University of Turin, who had worked with the explosive material guncotton.

Education and ca ...

, who had synthesized nitroglycerin

Nitroglycerin (NG) (alternative spelling nitroglycerine), also known as trinitroglycerol (TNG), nitro, glyceryl trinitrate (GTN), or 1,2,3-trinitroxypropane, is a dense, colorless or pale yellow, oily, explosive liquid most commonly produced by ...

three years before. Sobrero strongly opposed the use of nitroglycerin because it was unpredictable, exploding when subjected to variable heat or pressure. But Nobel became interested in finding a way to control and use nitroglycerin

Nitroglycerin (NG) (alternative spelling nitroglycerine), also known as trinitroglycerol (TNG), nitro, glyceryl trinitrate (GTN), or 1,2,3-trinitroxypropane, is a dense, colorless or pale yellow, oily, explosive liquid most commonly produced by ...

as a commercially usable explosive; it had much more power than gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, charcoal (which is mostly carbon), and potassium nitrate, potassium ni ...

. In 1851 at age 18, he went to the United States for one year to study, working for a short period under Swedish-American inventor John Ericsson

John Ericsson (born Johan Ericsson; July 31, 1803 – March 8, 1889) was a Swedish-American engineer and inventor. He was active in England and the United States.

Ericsson collaborated on the design of the railroad steam locomotive Novelty (lo ...

, who designed the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

ironclad, USS ''Monitor''. Nobel filed his first patent, an English patent for a gas meter

A gas meter is a specialized flow meter, used to measure the volume of fuel gases such as natural gas and liquefied petroleum gas. Gas meters are used at residential, commercial, and industrial buildings that consume fuel gas supplied by a g ...

, in 1857, while his first Swedish patent, which he received in 1863, was on "ways to prepare gunpowder". The family factory produced armaments

A weapon, arm, or armament is any implement or device that is used to deter, threaten, inflict physical damage, harm, or kill. Weapons are used to increase the efficacy and efficiency of activities such as hunting, crime (e.g., murder), law ...

for the Crimean War

The Crimean War was fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, the Second French Empire, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and the Kingdom of Sardinia (1720–1861), Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont fro ...

(1853–1856), but had difficulty switching back to regular domestic production when the fighting ended and they filed for bankruptcy

Bankruptcy is a legal process through which people or other entities who cannot repay debts to creditors may seek relief from some or all of their debts. In most jurisdictions, bankruptcy is imposed by a court order, often initiated by the deb ...

. In 1859, Nobel's father left his factory in the care of the second son, Ludvig Nobel

Ludvig Immanuel Nobel ( ; ; ; 27 July 1831 – 12 April 1888) was a Swedish-Russian engineer, a noted businessman and a humanitarian. One of the most prominent members of the Nobel family, he was the son of Immanuel Nobel (also an engineering pi ...

(1831–1888), who greatly improved the business. Nobel and his parents returned to Sweden from Russia and Nobel devoted himself to the study of explosives

An explosive (or explosive material) is a reactive substance that contains a great amount of potential energy that can produce an explosion if released suddenly, usually accompanied by the production of light, heat, sound, and pressure. An exp ...

, and especially to the safe manufacture and use of nitroglycerin. Nobel invented a detonator

A detonator is a device used to make an explosive or explosive device explode. Detonators come in a variety of types, depending on how they are initiated (chemically, mechanically, or electrically) and details of their inner working, which of ...

in 1863, and in 1865 designed the blasting cap

A detonator is a device used to make an explosive or explosive device explode. Detonators come in a variety of types, depending on how they are initiated (chemically, mechanically, or electrically) and details of their inner working, which of ...

.

On 3 September 1864, a shed used for preparation of nitroglycerin exploded at the factory in Heleneborg

Heleneborg is an estate on Södermalm, a part of the city of Stockholm, Sweden. It is opposite Långholmen island (home to Långholmen prison until 1975).

The property was bought in 1669 by Jonas Österling and was used by the Swedish tobacco m ...

, Stockholm, Sweden, killing five people, including Nobel's younger brother Emil. He was then deprived of his license to produce explosives. Fazed by the accident, Nobel founded the company Nitroglycerin AB in Vinterviken

Vinterviken ("Winter-cove") is a bay in the '' Mälaren'' lake in southern Stockholm, Sweden. Vinterviken is located in a valley surrounded by the Gröndal and Aspudden suburb areas.

Etymology

The origin of the name Vinterviken can be traced ...

so that he could continue to work in a more isolated area. Nobel invented dynamite

Dynamite is an explosive made of nitroglycerin, sorbents (such as powdered shells or clay), and Stabilizer (chemistry), stabilizers. It was invented by the Swedish people, Swedish chemist and engineer Alfred Nobel in Geesthacht, Northern German ...

in 1867, a substance easier and safer to handle than the more unstable nitroglycerin

Nitroglycerin (NG) (alternative spelling nitroglycerine), also known as trinitroglycerol (TNG), nitro, glyceryl trinitrate (GTN), or 1,2,3-trinitroxypropane, is a dense, colorless or pale yellow, oily, explosive liquid most commonly produced by ...

. Dynamite was patented in the US and the UK and was used extensively in mining

Mining is the Resource extraction, extraction of valuable geological materials and minerals from the surface of the Earth. Mining is required to obtain most materials that cannot be grown through agriculture, agricultural processes, or feasib ...

and the building of transport networks internationally. In 1875, Nobel invented gelignite

Gelignite (), also known as blasting gelatin or simply "jelly", is an explosive material consisting of collodion-cotton (a type of nitrocellulose or guncotton) dissolved in either nitroglycerine or nitroglycol and mixed with wood pulp and Potassi ...

, more stable and powerful than dynamite, and in 1887, patented ballistite

Ballistite is a smokeless propellant made from two high explosives, nitrocellulose and nitroglycerine. It was developed and patented by Alfred Nobel in the late 19th century.

Military adoption

Alfred Nobel patented Ballistite in 1887 while li ...

, a predecessor of cordite

Cordite is a family of smokeless propellants developed and produced in Britain since 1889 to replace black powder as a military firearm propellant. Like modern gunpowder, cordite is classified as a low explosive because of its slow burni ...

.

Nobel was elected a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences () is one of the Swedish Royal Academies, royal academies of Sweden. Founded on 2 June 1739, it is an independent, non-governmental scientific organization that takes special responsibility for promoting nat ...

in 1884, the same institution that would later select laureates

In English, the word laureate has come to signify eminence or association with literary awards or military glory. It is also used for recipients of the Nobel Prize, the Gandhi Peace Award, the Student Peace Prize, and for former music direc ...

for two of the Nobel prizes, and he received an honorary doctorate

An honorary degree is an academic degree for which a university (or other degree-awarding institution) has waived all of the usual requirements. It is also known by the Latin phrases ''honoris causa'' ("for the sake of the honour") or '' ad hon ...

from Uppsala University

Uppsala University (UU) () is a public university, public research university in Uppsala, Sweden. Founded in 1477, it is the List of universities in Sweden, oldest university in Sweden and the Nordic countries still in operation.

Initially fou ...

in 1893. Nobel's brothers Ludvig and Robert founded the oil company Branobel

The Petroleum Production Company Nobel Brothers, Limited, or Branobel (short for братьев Нобель "brat'yev Nobel" – "Nobel Brothers" in Russian), was an oil company set up by Ludvig Nobel and Baron Peter von Bilderling. It operat ...

and became hugely rich in their own right. Nobel invested in these and amassed great wealth through the development of these new oil regions. It operated mainly in Baku

Baku (, ; ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Azerbaijan, largest city of Azerbaijan, as well as the largest city on the Caspian Sea and in the Caucasus region. Baku is below sea level, which makes it the List of capital ci ...

, Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan, officially the Republic of Azerbaijan, is a Boundaries between the continents, transcontinental and landlocked country at the boundary of West Asia and Eastern Europe. It is a part of the South Caucasus region and is bounded by ...

, but also in Cheleken

Hazar (until 1999 known as Çeleken, also written Cheleken; ; Persian: Chaharken ) is a seaport town located on the Cheleken Peninsula of the Caspian Sea. It is directly subordinate to the city of Balkanabat in Balkan Province of western Turkm ...

, Turkmenistan

Turkmenistan is a landlocked country in Central Asia bordered by Kazakhstan to the northwest, Uzbekistan to the north, east and northeast, Afghanistan to the southeast, Iran to the south and southwest and the Caspian Sea to the west. Ash ...

. During his life, Nobel was issued 355 patent

A patent is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the legal right to exclude others from making, using, or selling an invention for a limited period of time in exchange for publishing an sufficiency of disclosure, enabling discl ...

s internationally, and by his death, his business had established more than 90 explosives and armament factories, despite his apparently pacifist

Pacifism is the opposition to war or violence. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaigner Émile Arnaud and adopted by other peace activists at the tenth Universal Peace Congress in Glasgow in 1901. A related term is ''a ...

character.

Inventions

Nobel found that whennitroglycerin

Nitroglycerin (NG) (alternative spelling nitroglycerine), also known as trinitroglycerol (TNG), nitro, glyceryl trinitrate (GTN), or 1,2,3-trinitroxypropane, is a dense, colorless or pale yellow, oily, explosive liquid most commonly produced by ...

was incorporated in an absorbent inert substance like ''kieselguhr'' (diatomaceous earth

Diatomaceous earth ( ), also known as diatomite ( ), celite, or kieselguhr, is a naturally occurring, soft, siliceous rock, siliceous sedimentary rock that can be crumbled into a fine white to off-white powder. It has a particle size ranging fr ...

) it became safer and more convenient to handle, and this mixture he patented in 1867 as "dynamite". Nobel demonstrated his explosive for the first time that year, at a quarry in Redhill, Surrey

Surrey () is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Greater London to the northeast, Kent to the east, East Sussex, East and West Sussex to the south, and Hampshire and Berkshire to the wes ...

, England. In order to help reestablish his name and improve the image of his business from the earlier controversies associated with dangerous explosives, Nobel had also considered naming the highly powerful substance "Nobel's Safety Powder", which is the text used in his patent, but settled with Dynamite instead, referring to the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

word for "power" ().

Nobel later combined nitroglycerin with various nitrocellulose compounds, similar to collodion

Collodion is a flammable, syrupy solution of nitrocellulose in Diethyl ether, ether and Alcohol (chemistry), alcohol. There are two basic types: flexible and non-flexible. The flexible type is often used as a surgical dressing or to hold dressings ...

, but settled on a more efficient recipe combining another nitrate explosive, and obtained a transparent, jelly-like substance, which was a more powerful explosive than dynamite. Gelignite

Gelignite (), also known as blasting gelatin or simply "jelly", is an explosive material consisting of collodion-cotton (a type of nitrocellulose or guncotton) dissolved in either nitroglycerine or nitroglycol and mixed with wood pulp and Potassi ...

, or blasting gelatin, as it was named, was patented in 1876; and was followed by a host of similar combinations, modified by the addition of potassium nitrate and various other substances. Gelignite was more stable, powerful, transportable and conveniently formed to fit into bored holes, like those used in drilling and mining, than the previously used compounds. It was adopted as the standard technology for mining in the "Age of Engineering", bringing Nobel a great amount of financial success, though at a cost to his health. An offshoot of this research resulted in Nobel's invention of ballistite

Ballistite is a smokeless propellant made from two high explosives, nitrocellulose and nitroglycerine. It was developed and patented by Alfred Nobel in the late 19th century.

Military adoption

Alfred Nobel patented Ballistite in 1887 while li ...

, the precursor of many modern smokeless powder explosives and still used as a rocket propellant.

Nobel Prize

There is a well known story about the origin of the Nobel Prize, although historians have been unable to verify it and some dismiss the story as a myth. In 1888, the death of his brother Ludvig supposedly caused several newspapers to publishobituaries

An obituary (obit for short) is an article about a recently deceased person. Newspapers often publish obituaries as news articles. Although obituaries tend to focus on positive aspects of the subject's life, this is not always the case. Acco ...

of Alfred in error. One French newspaper condemned him for his invention of military explosives—in many versions of the story, dynamite is quoted, although this was mainly used for civilian applications—and this is said to have brought about his decision to leave a better legacy after his death. The obituary stated, ' ("The merchant of death is dead"), and went on to say, "Dr. Alfred Nobel, who became rich by finding ways to kill more people faster than ever before, died yesterday." Nobel read the obituary and was appalled at the idea that he would be remembered in this way. His decision to posthumously donate the majority of his wealth to found the Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; ; ) are awards administered by the Nobel Foundation and granted in accordance with the principle of "for the greatest benefit to humankind". The prizes were first awarded in 1901, marking the fifth anniversary of Alfred N ...

has been credited to him wanting to leave behind a better legacy. However, it has been questioned whether or not the obituary in question actually existed.

On 27 November 1895, at the Swedish

Swedish or ' may refer to:

Anything from or related to Sweden, a country in Northern Europe. Or, specifically:

* Swedish language, a North Germanic language spoken primarily in Sweden and Finland

** Swedish alphabet, the official alphabet used by ...

- Norwegian Club in Paris, Nobel signed his last will and testament and set aside the bulk of his estate to establish the Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; ; ) are awards administered by the Nobel Foundation and granted in accordance with the principle of "for the greatest benefit to humankind". The prizes were first awarded in 1901, marking the fifth anniversary of Alfred N ...

s, to be awarded annually without distinction of nationality. After taxes and bequests to individuals, Nobel's will allocated 94% of his total assets, 31,225,000 Swedish kronor

The krona (; plural: ''kronor''; currency sign, sign: kr; ISO 4217, code: SEK) is the currency of Sweden. Both the ISO code "SEK" and currency sign "kr" are in common use for the krona; the former precedes or follows the value, the latter usual ...

, to establish the five Nobel Prizes. By 2022, the foundation had approximately 6 billion Swedish Kronor of invested capital.

The first three of these prizes are awarded for eminence in physical science, in chemistry and in medical science or physiology; the fourth is for literary work "in an ideal direction" and the fifth prize is to be given to the person or society that renders the greatest service to the cause of international fraternity

A fraternity (; whence, "wikt:brotherhood, brotherhood") or fraternal organization is an organization, society, club (organization), club or fraternal order traditionally of men but also women associated together for various religious or secular ...

, in the suppression or reduction of standing armies, or in the establishment or furtherance of peace congresses.

The formulation for the literary prize being given for a work "in an ideal direction" (' in Swedish) is cryptic and has caused much confusion. For many years, the Swedish Academy interpreted "ideal" as "idealistic" (') and used it as a reason not to give the prize to important but less romantic authors, such as Henrik Ibsen

Henrik Johan Ibsen (; ; 20 March 1828 – 23 May 1906) was a Norwegian playwright, poet and actor. Ibsen is considered the world's pre-eminent dramatist of the 19th century and is often referred to as "the father of modern drama." He pioneered ...

and Leo Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy Tolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; ,Throughout Tolstoy's whole life, his name was written as using Reforms of Russian orthography#The post-revolution re ...

. This interpretation has since been revised, and the prize has been awarded to, for example, Dario Fo

Dario Luigi Angelo Fo (; 24 March 1926 – 13 October 2016) was an Italian playwright, actor, theatre director, stage designer, songwriter, political campaigner for the Italian left wing and the recipient of the 1997 Nobel Prize in Literature. ...

and José Saramago

José de Sousa Saramago (; 16 November 1922 – 18 June 2010) was a Portuguese people, Portuguese writer. He was the recipient of the 1998 Nobel Prize in Literature for his "parables sustained by imagination, compassion and irony [with which ...

, who do not belong to the camp of literary idealism.

There was room for interpretation by the bodies he had named for deciding on the physical sciences and chemistry prizes, given that he had not consulted them before making the will. In his one-page testament, he stipulated that the money go to discoveries or inventions in the physical sciences and to discoveries or improvements in chemistry. He had opened the door to technological awards, but had not left instructions on how to deal with the distinction between science and technology. Since the deciding bodies he had chosen were more concerned with the former, the prizes went to scientists more often than engineers, technicians or other inventors.

Sweden's central bank Sveriges Riksbank celebrated its 300th anniversary in 1968 by donating a large sum of money to the Nobel Foundation to be used to set up a sixth prize in the field of economics in honor of Alfred Nobel. In 2001, Alfred Nobel's great-great-nephew, Peter Nobel (born 1931), asked the Bank of Sweden to differentiate its award to economists given "in Alfred Nobel's memory" from the five other awards. This request added to the controversy over whether the Bank of Sweden Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel

The Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, officially the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel (), commonly referred to as the Nobel Prize in Economics(), is an award in the field of Economic Sciences, economi ...

is actually a legitimate "Nobel Prize".

Health issues and death

In his letters to his mistress, Hess, Nobel described constant pain, debilitating migraines, and "paralyzing" fatigue, leading some to believe that he suffered fromfibromyalgia

Fibromyalgia (FM) is a functional somatic syndrome with symptoms of widespread chronic pain, accompanied by fatigue, sleep disturbance including awakening unrefreshed, and Cognitive deficit, cognitive symptoms. Other symptoms can include he ...

. However, his concerns at the time were dismissed as hypochondria

Hypochondriasis or hypochondria is a condition in which a person is excessively and unduly worried about having a serious illness. Hypochondria is an old concept whose meaning has repeatedly changed over its lifespan. It has been claimed that th ...

, leading to further depression.

By 1895, Nobel had developed angina pectoris

Angina, also known as angina pectoris, is chest pain or pressure, usually caused by insufficient blood flow to the heart muscle (myocardium). It is most commonly a symptom of coronary artery disease.

Angina is typically the result of part ...

.

On 27 November 1895, he finalized his will and testament

A will and testament is a legal document that expresses a person's (testator) wishes as to how their property (estate (law), estate) is to be distributed after their death and as to which person (executor) is to manage the property until its fi ...

, leaving most of his wealth in trust, unbeknownst to his family, to fund the Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; ; ) are awards administered by the Nobel Foundation and granted in accordance with the principle of "for the greatest benefit to humankind". The prizes were first awarded in 1901, marking the fifth anniversary of Alfred N ...

awards.

On 10 December 1896, he suffered a stroke

Stroke is a medical condition in which poor cerebral circulation, blood flow to a part of the brain causes cell death. There are two main types of stroke: brain ischemia, ischemic, due to lack of blood flow, and intracranial hemorrhage, hemor ...

/intracerebral hemorrhage

Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), also known as hemorrhagic stroke, is a sudden bleeding into Intraparenchymal hemorrhage, the tissues of the brain (i.e. the parenchyma), into its Intraventricular hemorrhage, ventricles, or into both. An ICH is ...

and was first partially paralyzed and then died, aged 63. He is buried in Norra begravningsplatsen

Norra begravningsplatsen, literally "The Northern Burial Place" in Swedish, is a major cemetery of the Stockholm urban area, located in Solna Municipality. Inaugurated on 9 June 1827, it is the burial site for a number of Swedish notables.

Th ...

in Stockholm.

Based on his experimentation with explosives, his strenuous work habit, and the decline in his health at the end of the 1870s, some hypothesize that nitroglycerine

Nitroglycerin (NG) (alternative spelling nitroglycerine), also known as trinitroglycerol (TNG), nitro, glyceryl trinitrate (GTN), or 1,2,3-trinitroxypropane, is a dense, colorless or pale yellow, oily, explosive liquid most commonly produced by ...

poisoning was a contributing factor to his death.

Personal life

Religion

Nobel wasLutheran

Lutheranism is a major branch of Protestantism that emerged under the work of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German friar and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practices of the Catholic Church launched ...

and, during his years living in Paris, he regularly attended the Church of Sweden Abroad

The Church of Sweden Abroad (, SKUT) is an institution of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Sweden. The Church of Sweden Abroad has more than 40 parishes throughout the world, concentrated in Western Europe. Another 80 cities are served by visitin ...

led by pastor Nathan Söderblom

Lars Olof Jonathan Söderblom (; 15 January 1866 – 12 July 1931) was a Swedish bishop. He was the Church of Sweden Archbishop of Uppsala from 1914 to 1931, and recipient of the 1930 Nobel Peace Prize. He is commemorated in the Calendar of ...

who received the Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize (Swedish language, Swedish and ) is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the Will and testament, will of Sweden, Swedish industrialist, inventor, and armaments manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Nobe ...

in 1930. He was an agnostic

Agnosticism is the view or belief that the existence of God, the divine, or the supernatural is either unknowable in principle or unknown in fact. (page 56 in 1967 edition) It can also mean an apathy towards such religious belief and refer to ...

in youth and became an atheist

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the existence of deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there no ...

later in life, though he still donated generously to the Church.

Romantic relationships and personality

Nobel remained a solitary character, given to periods of depression. He never married, although his biographers note that he had at least three loves. His first love was in Russia with a girl named Alexandra who rejected hismarriage proposal

A marriage proposal is a custom or ritual, common in Western cultures, in which one member of a couple asks the other for their hand in marriage. If accepted, it marks the initiation of engagement, a mutual promise of later marriage.

Norms a ...

.

In 1876, Austro-Bohemian Countess Bertha von Suttner

Baroness Bertha Sophie Felicitas von Suttner (; ; 9 June 184321 June 1914) was an Bohemian nobility, Austro-Bohemian noblewoman, Pacifism, pacifist and novelist. In 1905, she became the second female Nobel laureate (after Marie Curie in 1903), th ...

became his secretary, but she left him after a brief stay to marry her previous lover Baron Arthur Gundaccar von Suttner. Her contact with Nobel was brief, yet she corresponded with him until his death in 1896, and probably influenced his decision to include the Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize (Swedish language, Swedish and ) is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the Will and testament, will of Sweden, Swedish industrialist, inventor, and armaments manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Nobe ...

in his will. She was awarded the 1905 Nobel Peace prize "for her sincere peace activities".

Nobel's longest-lasting romance was an 18-year relationship with Sofija Hess from Celje

Celje (, , ) is the List of cities and towns in Slovenia, third-largest city in Slovenia. It is a regional center of the traditional Slovenian region of Styria (Slovenia), Styria and the administrative seat of the City Municipality of Celje. Th ...

whom he met in 1876 in Baden bei Wien

Baden (Central Bavarian: ''Bodn''), unofficially distinguished from Baden (disambiguation), other Badens as Baden bei Wien (Baden near Vienna), is a spa town in Austria. It serves as the capital of Baden (district of Austria), Baden District in t ...

, where she worked as an employee in a flower shop that catered to wealthy clientele. The extent of their relationship was revealed by a collection of 221 letters sent by Nobel to Hess over 15 years. At the time that they met, Nobel was 43 years old while Hess was 26. Their relationship, which was not merely platonic, ended when she became pregnant from another man, although Nobel continued to support her financially until Hess married her child's father to avoid being ostracized as a whore. Hess was a Jewish Christian and the letters include remarks by Nobel characterized as antisemitism

Antisemitism or Jew-hatred is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Whether antisemitism is considered a form of racism depends on the school of thought. Antisemi ...

. Nobel also displayed characteristics of chauvinism

Chauvinism ( ) is the unreasonable belief in the superiority or dominance of one's own group or people, who are seen as strong and virtuous, while others are considered weak, unworthy, or inferior. The ''Encyclopaedia Britannica'' describes it ...

in the letters writing to Hess: "You neither work, nor write, nor read, nor think" and guilted her, writing "I have for years now sacrificed out of purely noble motives my time, my duties, my intellectual life, my reputation".

Residences

Nobel traveled for much of his business life, maintaining companies in Europe and America. From 1865 to 1873, Nobel lived in Krümmel (now in the municipality ofGeesthacht

Geesthacht () is the largest city in the Lauenburg (district), District of the Duchy of Lauenburg (Herzogtum Lauenburg) in Schleswig-Holstein in Northern Germany, south-east of Hamburg on the right bank of the Elbe, River Elbe.

History

A church ...

, near Hamburg

Hamburg (, ; ), officially the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg,. is the List of cities in Germany by population, second-largest city in Germany after Berlin and List of cities in the European Union by population within city limits, 7th-lar ...

). From 1873 to 1891, he lived in a house in the Avenue Malakoff in Paris.

In 1891, after being accused of high treason against France for selling Ballistite

Ballistite is a smokeless propellant made from two high explosives, nitrocellulose and nitroglycerine. It was developed and patented by Alfred Nobel in the late 19th century.

Military adoption

Alfred Nobel patented Ballistite in 1887 while li ...

to Italy, he moved from Paris to Sanremo

Sanremo, also spelled San Remo in English and formerly in Italian, is a (municipality) on the Mediterranean coast of Liguria, in northwestern Italy. Founded in Roman times, it has a population of 55,000, and is known as a tourist destination ...

, Italy, acquiring Villa Nobel

Villa Nobel is a historic villa located in Sanremo, Italy, once owned by Alfred Nobel.

History

Villa Nobel, built in 1871 and located on Corso Cavallotti in Sanremo, was commissioned by Rivoli pharmacist Pietro Vacchieri, who had purchased the ...

, overlooking the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Eur ...

, where he died in 1896.

In 1894, when he acquired Bofors-Gullspång, the Björkborn Manor

Björkborn Manor (, ) is a manor house and the very last residence of Alfred Nobel in Sweden. The manor is located in Karlskoga Municipality, Örebro County, Sweden. The current-standing white-colored manor house was built in the 1810s, but the hi ...

was included, where he stayed during the summers. It is now a museum.

Monument to Alfred Nobel

The ''Monument to Alfred Nobel'' (, ) is in Saint Petersburg along theBolshaya Nevka River

The Great Nevka or Bolshaya Nevka () is an arm of the Neva that begins about below the Liteyny Bridge in Saint Petersburg.

Attractions

* Bridges

** Samson Bridge

** Grenadiers Bridge

** Kantemirovsky Bridge

** Ushakovsky Bridge

** 3rd Yelagi ...

on Petrogradskaya Embankment, the street where Nobel's family lived until 1859. It was dedicated in 1991 to mark the 90th anniversary of the first Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; ; ) are awards administered by the Nobel Foundation and granted in accordance with the principle of "for the greatest benefit to humankind". The prizes were first awarded in 1901, marking the fifth anniversary of Alfred N ...

presentation. Diplomat Thomas Bertelman and Professor Arkady Melua

Arkady Ivanovich Melua (7 February 1950) is the general director and editor-in-chief of the scientific publishing house, Humanistica.

Life and work

Starting in 1969, Melua served and worked as an engineer at the Ministry of Defense facilitie ...

were initiators of the creation of the monument in 1989 and they provided funds for the establishment of the monument. The abstract metal sculpture was designed by local artists Sergey Alipov and Pavel Shevchenko, and appears to be an explosion or branches of a tree.

Criticism

Criticism of Nobel focuses on his leading role in weapons manufacturing and sales. Some people question his motives in creating his prizes, suggesting they are intended to improve his reputation.Antisemitism

Nobel has also been criticized for displays ofantisemitism

Antisemitism or Jew-hatred is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Whether antisemitism is considered a form of racism depends on the school of thought. Antisemi ...

. In his letters to Hess, he wrote "In my experience, ewsnever do anything out of good will. They act merely out of selfishness or a desire to show off .... among selfish and inconsiderate people they are the most selfish and inconsiderate... all others exist to be fleeced."

References

Further reading

* Asbrink, Brita (Summer 2002)"The Nobels in Baku"

in ''Azerbaijan International'', Vol 10.2, 56–59. * Evlanoff, M. and Fluor, M. ''Alfred Nobel – The Loneliest Millionaire''. Los Angeles, Ward Ritchie Press, 1969. * * Schück, H, and Sohlman, R., (1929). ''The Life of Alfred Nobel'', transl.

Brian Lunn

Brian Lunn (1893–1956) was a British writer and translator.

He was born in Bloomsbury, London, youngest of three sons (there being also a daughter) of Methodist parents Sir Henry Lunn (1859-1939) and Mary Ethel, née Moore, daughter of a ca ...

, London: William Heineman Ltd.

* Sohlman, R. ''The Legacy of Alfred Nobel'', transl. Schubert E. London: The Bodley Head, 1983 (Swedish original, ''Ett Testamente'', published in 1950).

* Alfred Nobel US Patent No 78,317, dated 26 May 1868

External links

The Man Behind the Prize – Alfred Nobel

(mostly in Russian) * * * ttps://www.researchgate.net/publication/338139787_Alfred_Nobel_and_his_unknown_coworker Alfred Nobel and his unknown coworker {{DEFAULTSORT:Nobel, Alfred 1833 births 1896 deaths 19th-century Swedish businesspeople 19th-century Swedish chemists 19th-century Swedish engineers 19th-century Swedish philanthropists 19th-century Swedish scientists Bofors people Burials at Norra begravningsplatsen Engineers from Stockholm Explosives engineers Members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

Alfred

Alfred may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

*''Alfred J. Kwak'', Dutch-German-Japanese anime television series

* ''Alfred'' (Arne opera), a 1740 masque by Thomas Arne

* ''Alfred'' (Dvořák), an 1870 opera by Antonín Dvořák

*"Alfred (Interlu ...

Nobel Prize