Albion W. Tourgée on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Albion Winegar Tourgée (May 2, 1838 – May 21, 1905) was an American soldier, lawyer, writer, politician, and diplomat. Wounded in the Civil War, he relocated to North Carolina afterward, where he became involved in

Born in rural Williamsfield, Ohio, on May 2, 1838, Tourgée was the son of farmer Valentine Tourgée and his wife Louisa Emma Winegar. His mother died when he was five. He attended common schools in

Born in rural Williamsfield, Ohio, on May 2, 1838, Tourgée was the son of farmer Valentine Tourgée and his wife Louisa Emma Winegar. His mother died when he was five. He attended common schools in

Fighting in the

Fighting in the

"Tourgée" in ''The American National Biography''

(2000) * Otto Olsen, ''Carpetbagger's Crusade: The Life of Albion Winegar Tourgée'' (1965) * * Roy F. Dibble, ''Albion W. Tourgée'' (1921) * J. G. de Roulhac Hamilton, ''Reconstruction in North Carolina'' (1914) * "Albion W. Tourgée Dead.", ''

"Albion Winegar Tourgee"

(North Carolina Press 1979)

New York Heritage - Albion Winegar Tourgée Collection

*New York Heritage online exhibit:

Albion Tourgee, from Civil War to Civil Rights: Documenting an American Dialogue on Humanity, Equality, and Justice

' * (1887)

Students Secure Marker for Reconstruction Era Lawyer Albion Tourgée

{{DEFAULTSORT:Tourgee, Albion Winegar 19th-century American novelists American civil rights activists American male novelists Union army officers People of Ohio in the American Civil War People of New York (state) in the American Civil War American Civil War prisoners of war People from Ashtabula County, Ohio People from Mayville, New York Indiana lawyers University of Rochester alumni North Carolina lawyers North Carolina state court judges North Carolina Republicans 1838 births 1905 deaths New York (state) Republicans 19th-century American male writers Activists from Ohio American expatriates in France 19th-century North Carolina state court judges 19th-century pseudonymous writers 19th-century American essayists American male essayists American legal writers American historical novelists Writers of historical fiction set in the early modern period Writers from Ohio 19th-century American short story writers American male short story writers 19th-century American non-fiction writers American male non-fiction writers Founders of American schools and colleges American anti-racism activists 19th-century American historians Historians from Ohio 19th-century Ohio politicians Ohio Republicans Writers from North Carolina Activists from North Carolina Writers from New York (state)

Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Union ...

activities. He served in the constitutional convention and later in the state legislature. Albion Tourgée is also a pioneer civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' political freedom, freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and ...

activist who founded the National Citizens' Rights Association and Bennett College

Bennett College is a private university, private historically black colleges and universities, historically black liberal arts college, liberal arts Women's colleges in the Southern United States, college for women in Greensboro, North Carolin ...

as a normal school for freedmen

A freedman or freedwoman is a person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, slaves were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their owners), emancipation (granted freedom as part of a larger group), or self- ...

in North Carolina (it has been a women's college since 1926). Tourgée represented Tabitha Ann Holton in the Supreme Court of North Carolina, who applied and became the first female lawyer in North Carolina and in the Southern United States.

An ally of African Americans since his Civil War days, later in his career Tourgée was asked to aid a committee in New Orleans that was challenging segregation on railways in Louisiana

Louisiana ( ; ; ) is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It borders Texas to the west, Arkansas to the north, and Mississippi to the east. Of the 50 U.S. states, it ranks 31st in area and 25 ...

, and he was appointed the lead attorney in the landmark ''Plessy v. Ferguson

''Plessy v. Ferguson'', 163 U.S. 537 (1896), was a landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision ruling that racial segregation laws did not violate the U.S. Constitution as long as the facilities for each race were equal in quality, a doctrine that ...

'' (1896) case. The committee was dismayed when the United States Supreme Court ruled that "separate but equal" public facilities were constitutional; this enabled segregation for decades. Historian Mark Elliott credits Tourgée with introducing the metaphor of " color blind justice" into legal discourse.Elliott, ''Color Blind Justice...''.

Early life

Born in rural Williamsfield, Ohio, on May 2, 1838, Tourgée was the son of farmer Valentine Tourgée and his wife Louisa Emma Winegar. His mother died when he was five. He attended common schools in

Born in rural Williamsfield, Ohio, on May 2, 1838, Tourgée was the son of farmer Valentine Tourgée and his wife Louisa Emma Winegar. His mother died when he was five. He attended common schools in Ashtabula County

Ashtabula County ( ) is the northeasternmost county in the U.S. state of Ohio. As of the 2020 census, the population was 97,574. The county seat is Jefferson, while its largest city is Ashtabula. The county was created in 1808 and later organ ...

and in Lee, Massachusetts

Lee is a town in Berkshire County, Massachusetts, United States. It is part of the Pittsfield, Massachusetts, metropolitan statistical area. The population was 5,788 at the 2020 census. Lee, which includes the villages of South and East Lee, is ...

, where he lived for two years with an uncle.

Tourgée entered the University of Rochester

The University of Rochester is a private university, private research university in Rochester, New York, United States. It was founded in 1850 and moved into its current campus, next to the Genesee River in 1930. With approximately 30,000 full ...

in 1859. He showed no interest in politics until the university attempted to ban the Wide Awakes, a paramilitary

A paramilitary is a military that is not a part of a country's official or legitimate armed forces. The Oxford English Dictionary traces the use of the term "paramilitary" as far back as 1934.

Overview

Though a paramilitary is, by definiti ...

campaign organization affiliated with the Republican Party. Tourgée took on the administration and succeeded in reaching a compromise with the University president. Due to lack of funds, he had to leave the university in 1861, before completing his degree. He taught school to save money in order to return to Rochester.

After the outbreak of the Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

in April of the same year, Tourgée enlisted in the 27th New York Volunteer Infantry before completing his collegiate studies. Tourgée was awarded an A.B. degree ''in absentia'' in June 1862, as was a common practice at many universities for students who had enlisted before completing degrees.

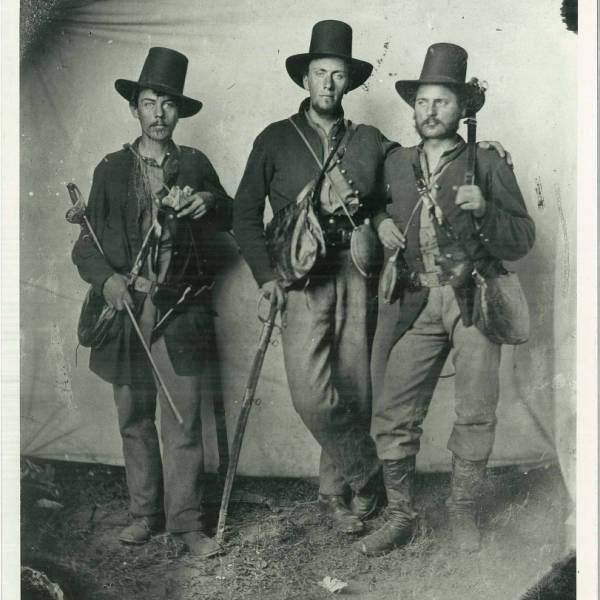

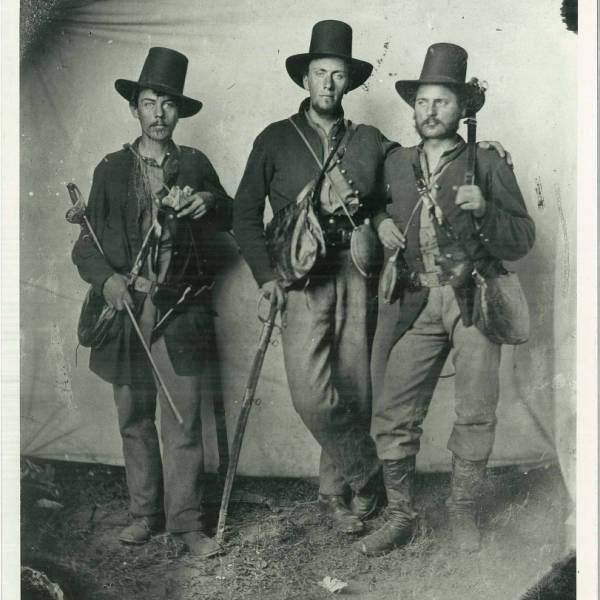

Military service

Fighting in the

Fighting in the First Battle of Bull Run

The First Battle of Bull Run, called the Battle of First Manassas

. by Confederate States ...

, the first major battle of the war, Tourgée was wounded in the spine when he was accidentally struck by a Union gun carriage during retreat. He suffered temporary paralysis and a permanent back problem that plagued him for the rest of his life. Upon recovering sufficiently to resume his military career, he was commissioned as a . by Confederate States ...

first lieutenant

First lieutenant is a commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces; in some forces, it is an appointment.

The rank of lieutenant has different meanings in different military formations, but in most forces it is sub-divided into a se ...

in the 105th Ohio Volunteer Infantry. At the Battle of Perryville

The Battle of Perryville, also known as the Battle of Chaplin Hills, was fought on October 8, 1862, in the Chaplin Hills west of Perryville, Kentucky, as the culmination of the Confederate Heartland Offensive (Kentucky Campaign) during the Ame ...

, he was again wounded.

On January 21, 1863, Tourgée was captured near Murfreesboro, Tennessee

Murfreesboro is a city in Rutherford County, Tennessee, United States, and its county seat. Its population was 165,430 according to the 2023 census estimate, up from 108,755 residents certified in 2010 United States census, 2010. Murfreesboro i ...

and was held as a prisoner-of-war in Libby Prison

Libby Prison was a Confederate States of America, Confederate prison at Richmond, Virginia, during the American Civil War. In 1862 it was designated to hold officer prisoners from the Union Army, taking in numbers from the nearby Seven Days battl ...

in Richmond, Virginia

Richmond ( ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the Commonwealth (U.S. state), U.S. commonwealth of Virginia. Incorporated in 1742, Richmond has been an independent city (United States), independent city since 1871. ...

, before his exchange on May 8, 1863. He rejoined Union forces and resumed his duties and fought at the battles of Chickamauga and Chattanooga

Chattanooga ( ) is a city in Hamilton County, Tennessee, United States, and its county seat. It is located along the Tennessee River and borders Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the south. With a population of 181,099 in 2020, it is Tennessee ...

. Under pressure from the military because of his medical condition, Tourgée resigned his commission on December 6, 1863.

He returned to Ohio, where he married Emma Doiska Kilbourne, his childhood sweetheart. They had one child.

Reconstruction era

After the war, Tourgée studied law with an established firm, in an apprenticeship, and gained entrance to the Ohio bar. The Tourgée couple soon moved toGreensboro, North Carolina

Greensboro (; ) is a city in Guilford County, North Carolina, United States, and its county seat. At the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, its population was 299,035; it was estimated to be 307,381 in 2024. It is the List of municipalitie ...

, where he could live in a warmer climate better suited to his war injuries. While there, he established himself as a lawyer, farmer, and editor, working for the Republican newspaper, the ''Union Registrar''. In 1866, he attended the Convention of the Southern Loyalists, where he unsuccessfully attempted to push through a resolution for African-American suffrage.

Considered by locals to be a carpetbagger

In the history of the United States, carpetbagger is a largely historical pejorative used by Southerners to describe allegedly opportunistic or disruptive Northerners who came to the Southern states after the American Civil War and were pe ...

because he had come from the North, Tourgée participated in several roles during Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Union ...

. He drew from this period for later novels that he wrote about the time period. In 1868 he was elected to represent Guilford County at the state constitutional convention, which was dominated by Republicans. Tourgée was influential at the convention, shaping its determinations on the judiciary, local government, and public welfare. He successfully advocated for equal political and civil rights for all citizens; ending property qualifications for jury duty and officeholding; requiring popular election of all state officers, including judges; founding free public education; abolishing the use of whipping posts as punishment for persons convicted of crimes; judicial reform; and uniform taxation.

Tourgée was elected to the 7th District superior court

In common law systems, a superior court is a court of general jurisdiction over civil and criminal legal cases. A superior court is "superior" in relation to a court with limited jurisdiction (see small claims court), which is restricted to civil ...

as a judge, serving from 1868 to 1874. During this period he confronted the increasingly violent Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to KKK or Klan, is an American Protestant-led Christian terrorism, Christian extremist, white supremacist, Right-wing terrorism, far-right hate group. It was founded in 1865 during Reconstruction era, ...

, which was very powerful in his district and had members who repeatedly threatened his life. During this time, Tourgée was also appointed as one of three commissioners in charge of codifying North Carolina's previously dual law-code system into one. The new codified civil procedures, at first strongly opposed by the state's legal practitioners, proved in time the most flexible, and informal system in the Union. Among his other activities, Tourgée served as a delegate to the 1875 state constitutional convention and ran a losing campaign for Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

in 1878.

Literary life

Albion's first literary endeavor was the novel ''Toinette,'' written between 1868 and 1869 while he was living in North Carolina. It was not published until 1874, and then under the pseudonym "Henry Churton." It was renamed ''A Royal Gentleman'' when it was republished in 1881. Financial success came after his novel ''A Fool's Errand, by One of the Fools'' was published in late 1879. Based on his experiences of Reconstruction, the novel sold 200,000 copies. Its sequel, ''Bricks Without Straw'' (1880), also was abestseller

A bestseller is a book or other media noted for its top selling status, with bestseller lists published by newspapers, magazines, and book store chains. Some lists are broken down into classifications and specialties (novel, nonfiction book, cookb ...

. It was unique among contemporary novels by white men about the South, as it presented events from the viewpoints of freedmen

A freedman or freedwoman is a person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, slaves were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their owners), emancipation (granted freedom as part of a larger group), or self- ...

, and depicts promises of freedom narrowed by postwar violence and discrimination against freedmen.

In 1881, Tourgée and his family returned north to Mayville, New York

Mayville is a Administrative divisions of New York#Village, village in the town of Chautauqua, New York. It is the county seat of Chautauqua County, New York, Chautauqua County. The population was 1,477 at the 2020 census, 13.7% less than in the ...

, near the Chautauqua Institution

The Chautauqua Institution ( ) is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit education center and summer resort for adults and youth located on in Chautauqua, New York, northwest of Jamestown, New York, Jamestown in the western southern tier of New York (state), N ...

in the western part of the state. He made his living as writer and editor of the literary weekly ''The Continent'', but it failed in 1884.

He wrote many more novels and essays in the next two decades, many set in the Lake Erie

Lake Erie ( ) is the fourth-largest lake by surface area of the five Great Lakes in North America and the eleventh-largest globally. It is the southernmost, shallowest, and smallest by volume of the Great Lakes and also has the shortest avera ...

region to which he had relocated. These included ''Button's Inn'' (1887), a novel about early Mormon

Mormons are a religious and cultural group related to Mormonism, the principal branch of the Latter Day Saint movement started by Joseph Smith in upstate New York during the 1820s. After Smith's death in 1844, the movement split into several ...

s, who founded their religion in the western part of New York. Called the "Burned Over District", this area was a center of religious fervor in the 19th century. One of his books explored social justice from a Christian perspective; this thought-provoking and controversial novel, ''Murvale Eastman: Christian Socialist'', was published in 1890.

''Plessy v. Ferguson'' case

Near the end of the 19th century, the Southern states had become dominated by white Democrats. The legislatures began to pass new constitutions (beginning withMississippi

Mississippi ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Alabama to the east, the Gulf of Mexico to the south, Louisiana to the s ...

in 1890) and laws to raise barriers to voter registration to suppress the black Republican vote and to impose legal segregation in public facilities. Louisiana

Louisiana ( ; ; ) is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It borders Texas to the west, Arkansas to the north, and Mississippi to the east. Of the 50 U.S. states, it ranks 31st in area and 25 ...

passed an 1890 law intended "to promote the comfort of passengers" by requiring all state railway companies "to provide equal but separate accommodations for the white and colored races, by providing separate coaches or compartments" on their passenger trains.

In September 1891 a group of prominent black leaders in New Orleans

New Orleans (commonly known as NOLA or The Big Easy among other nicknames) is a Consolidated city-county, consolidated city-parish located along the Mississippi River in the U.S. state of Louisiana. With a population of 383,997 at the 2020 ...

, made up of mostly men who had been free people of color

In the context of the history of slavery in the Americas, free people of color (; ) were primarily people of mixed African, European, and Native American descent who were not enslaved. However, the term also applied to people born free who we ...

before the Civil War, organized a "Citizens' Committee" to challenge this law on federal constitutional grounds. To assist them in their challenge, this group retained the legal services of "Judge Tourgée," as he was popularly known.

Perhaps considered the nation's most outspoken white Radical on the "race question" in the late 1880s and 1890s, Tourgée had called for resistance to the Louisiana law in his widely read newspaper column, ''A Bystander's Notes.'' Written for the ''Chicago Republican'' (later known as the ''Chicago Daily Inter Ocean'' and after 1872 known as the ''Chicago Record-Herald''), his column was syndicated in many newspapers across the country. Largely as a consequence of this column, "Judge Tourgée" had become well known in the black community for his bold denunciations of lynching

Lynching is an extrajudicial killing by a group. It is most often used to characterize informal public executions by a mob in order to punish an alleged or convicted transgressor or to intimidate others. It can also be an extreme form of i ...

, segregation, disfranchisement, white supremacy, and scientific racism. He was the first choice of the New Orleans Citizens' Committee's to lead their legal challenge to the new Louisiana segregation law.

As they developed their challenge, Tourgée played a strategic role, for instance suggesting that a light-skinned, mixed-race

The term multiracial people refers to people who are mixed with two or more

races and the term multi-ethnic people refers to people who are of more than one ethnicities. A variety of terms have been used both historically and presently for mul ...

African American challenge the law. Dan Desdunes, the son of prominent ''Citizens Committee'' leader Rodolphe Desdunes

Rodolphe Lucien Desdunes (; November 15, 1849 – August 14, 1928) was a Louisiana Creole civil rights activist, poet, historian, journalist, and customs officer primarily active in New Orleans, Louisiana.

In Louisiana, Desdunes served as a mili ...

, was initially selected, but his case was thrown out because he had been a passenger on an interstate train, where the court ruled that state law did not apply. Homer Plessy

Homer Adolph Plessy (born Homère Patris Plessy; 1858, 1862 or March 17, 1863 – March 1, 1925) was an American shoemaker and activist who was the plaintiff in the United States Supreme Court decision '' Plessy v. Ferguson''. He staged an act of ...

was selected next. He was arrested after boarding an intrastate train and refusing to move from a white to a "colored" car.

Tourgée, who was lead attorney for Homer Plessy, first deployed the term "color blindness" in his briefs in the ''Plessy'' case. He had used it on several prior occasions on behalf of the struggle for civil rights. Tourgée's first use of "color blindness" as a legal metaphor has been documented decades before, while he was serving as a Superior Court judge in North Carolina. In his dissent in ''Plessy'', Justice John Marshall Harlan

John Marshall Harlan (June 1, 1833 – October 14, 1911) was an American lawyer and politician who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1877 until his death in 1911. He is often called "The Great Disse ...

borrowed the metaphor of "color blindness" from Tourgée's legal brief.

Later life

In the wake of an 1892 lynching in Memphis known as the Peoples Grocery lynching, anti-lynching activistIda B. Wells

Ida Bell Wells-Barnett (July 16, 1862 – March 25, 1931) was an American investigative journalist, sociologist, educator, and early leader in the civil rights movement. She was one of the founders of the National Association for the Advance ...

wrote about the case. After the '' Memphis Commercial'' accused her of inciting the incident, she asked Tourgee to represent her in a libel case against the newspaper. Tourgée had largely retired from law (with the exception of his work with the New Orleans "Citizens' Committee") and refused. Tourgée recommended that Wells contact his friend, Ferdinand Lee Barnett, and Barnett agreed to take the case.

This may have been Barnett's introduction to Wells. They married two years later. Barnett came to agree with Tourgée's assessment: that the case did not have a good chance of being won. He said that a black woman would never win such a case heard by an all-white, all-male jury in Memphis, and Wells withdrew her suit. Wells and Barnett married in 1895.

In 1897, following Tourgée's involvement in the ''Plessy'' case, President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until Assassination of William McKinley, his assassination in 1901. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Repub ...

appointed him as U.S. consul

Consul (abbrev. ''cos.''; Latin plural ''consules'') was the title of one of the two chief magistrates of the Roman Republic, and subsequently also an important title under the Roman Empire. The title was used in other European city-states thro ...

to France. He sailed to Bordeaux

Bordeaux ( ; ; Gascon language, Gascon ; ) is a city on the river Garonne in the Gironde Departments of France, department, southwestern France. A port city, it is the capital of the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region, as well as the Prefectures in F ...

where he was based. About 1900, Tourgée joined the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States

The Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States (MOLLUS), or, simply, the Loyal Legion, is a United States military order organized on April 15, 1865, by three veteran officers of the Union Army. The original membership was consisted ...

, an influential Civil War veterans' organization of Union men who had been commissioned officers. He was assigned Companion No. 13949.

Tourgée served in France until his death in early 1905. He had been gravely ill for several months, but then appeared to rebound. The recovery was only brief, momentary, however, and he succumbed to acute uremia

Uremia is the condition of having high levels of urea in the blood. Urea is one of the primary components of urine. It can be defined as an excess in the blood of amino acid and protein metabolism end products, such as urea and creatinine, which ...

. The kidney damage was believed to be related to a Civil War wound.

Tourgée's ashes were interred at the Mayville Cemetery, in Mayville, New York. He is commemorated by a 12-foot granite obelisk

An obelisk (; , diminutive of (') ' spit, nail, pointed pillar') is a tall, slender, tapered monument with four sides and a pyramidal or pyramidion top. Originally constructed by Ancient Egyptians and called ''tekhenu'', the Greeks used th ...

inscribed thus: ''I pray thee

''Prithee'' is an archaic English interjection formed from a corruption of the phrase ''pray thee'' ( ask you o, which was initially an exclamation of contempt used to indicate a subject's triviality. The earliest recorded appearance of the w ...

then Write me as one that loves his fellow-man.''Crocker, Kathleen A., "Chautauqua County Lawyers Oppose Segregation: The Robert H. Jackson-Albion W. Tourgee Connection," ''Jamestown Post-Journal,'' April 24, 2004. Quotation from '' Abou ben Adhem'', by Leigh Hunt

James Henry Leigh Hunt (19 October 178428 August 1859), best known as Leigh Hunt, was an English critic, essayist and poet.

Hunt co-founded '' The Examiner'', a leading intellectual journal expounding radical principles. He was the centre ...

.

Books

Fiction *''Toinette'' (1874) *''Figs and Thistles: A Western Story'' (1879) *''A Fool's Errand'' (1879) *''Bricks Without Straw'' (1880) *Zouri's Christmas'' (1881) *''John Eax and Marmelon; or, The South Without the Shadow'' (1882) *''Hot Plowshares'' (1883) *''The Veteran and His Pipe'' (1886) *''Button's Inn'' (1887) *''Black Ice'' (1888) *''With Gauge and Swallow, Attorneys'' (1889) *''Murvale Eastman, Christian Socialist'' (1890) *''Pactolus Prime'' (1890) *89'' (1891) *''A Son of Old Harry'' (1892) *''Out of the Sunset Sea'' (1893) *''An Outing with the Queen of Hearts'' (1894) *''The Mortgage on the Hip-Roof House'' (1896) *''The Man Who Outlived Himself'' (1898) stories Nonfiction *''The Code of Civil Procedure of North Carolina'', with Barringer & Rodman (1878) *''An Appeal to Caesar'' (1884) *''Letters to a King'' (1888) *''The War of the Standards: Coin and Credit vs. Coin Without Credit'' (1896) *''The Story of a Thousand, Being a History of the 105th Volunteer Infantry, 1862-65'' (1896) *''A Civil War Diary'', ed by Dean H. Keller (post, 1965)Notes

References

* Mark Elliott, ''Color-Blind Justice: Albion Tourgée and the Quest for Racial Equality from the Civil War toPlessy v. Ferguson

''Plessy v. Ferguson'', 163 U.S. 537 (1896), was a landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision ruling that racial segregation laws did not violate the U.S. Constitution as long as the facilities for each race were equal in quality, a doctrine that ...

'' (2006).

* Michael Kent Curtis"Tourgée" in ''The American National Biography''

(2000) * Otto Olsen, ''Carpetbagger's Crusade: The Life of Albion Winegar Tourgée'' (1965) * * Roy F. Dibble, ''Albion W. Tourgée'' (1921) * J. G. de Roulhac Hamilton, ''Reconstruction in North Carolina'' (1914) * "Albion W. Tourgée Dead.", ''

The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'', May 22, 1905, p. 7.

* Dictionary of North Carolina Biography, William S. Powell, Ed."Albion Winegar Tourgee"

(North Carolina Press 1979)

External links

* *New York Heritage - Albion Winegar Tourgée Collection

*New York Heritage online exhibit:

Albion Tourgee, from Civil War to Civil Rights: Documenting an American Dialogue on Humanity, Equality, and Justice

' * (1887)

Students Secure Marker for Reconstruction Era Lawyer Albion Tourgée

{{DEFAULTSORT:Tourgee, Albion Winegar 19th-century American novelists American civil rights activists American male novelists Union army officers People of Ohio in the American Civil War People of New York (state) in the American Civil War American Civil War prisoners of war People from Ashtabula County, Ohio People from Mayville, New York Indiana lawyers University of Rochester alumni North Carolina lawyers North Carolina state court judges North Carolina Republicans 1838 births 1905 deaths New York (state) Republicans 19th-century American male writers Activists from Ohio American expatriates in France 19th-century North Carolina state court judges 19th-century pseudonymous writers 19th-century American essayists American male essayists American legal writers American historical novelists Writers of historical fiction set in the early modern period Writers from Ohio 19th-century American short story writers American male short story writers 19th-century American non-fiction writers American male non-fiction writers Founders of American schools and colleges American anti-racism activists 19th-century American historians Historians from Ohio 19th-century Ohio politicians Ohio Republicans Writers from North Carolina Activists from North Carolina Writers from New York (state)