Ahmed ʻUrabi on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Ahmed Urabi (;

The British were especially concerned that ʻUrabi would default on Egypt's massive debt and that he might try to gain control of the

The British were especially concerned that ʻUrabi would default on Egypt's massive debt and that he might try to gain control of the

Arabic

Arabic (, , or , ) is a Central Semitic languages, Central Semitic language of the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family spoken primarily in the Arab world. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) assigns lang ...

: ; 31 March 1841 – 21 September 1911), also known as Ahmed Ourabi or Orabi Pasha, was an Egyptian military officer. He was the first political and military leader in Egypt to rise from the ''fellahin

A fellah ( ; feminine ; plural ''fellaheen'' or ''fellahin'', , ) is a local peasant, usually a farmer or agricultural laborer in the Middle East and North Africa. The word derives from the Arabic word for "ploughman" or "tiller".

Due to a con ...

'' (peasantry). Urabi participated in an 1879 mutiny that developed into the ʻUrabi revolt

The ʻUrabi revolt, also known as the ʻUrabi Revolution (), was a nationalist uprising in the Khedivate of Egypt from 1879 to 1882. It was led by and named for Colonel Ahmed Urabi and sought to depose the khedive, Tewfik Pasha, and end Imperial ...

against the administration of Khedive Tewfik

Mohamed Tewfik Pasha ( ''Muḥammad Tawfīq Bāshā''; April 30 or 15 November 1852 – 7 January 1892), also known as Tawfiq of Egypt, was khedive of Khedivate of Egypt, Egypt and the Turco-Egyptian Sudan, Sudan between 1879 and 1892 and the s ...

, which was under the influence of an Anglo- French consortium

A consortium () is an association of two or more individuals, companies, organizations, or governments (or any combination of these entities) with the objective of participating in a common activity or pooling their resources for achieving a ...

. He was promoted to Tewfik's cabinet and began reforms of Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

's military and civil administrations, but the demonstrations in Alexandria

Alexandria ( ; ) is the List of cities and towns in Egypt#Largest cities, second largest city in Egypt and the List of coastal settlements of the Mediterranean Sea, largest city on the Mediterranean coast. It lies at the western edge of the Nile ...

of 1882 prompted a British bombardment and invasion

An invasion is a Offensive (military), military offensive of combatants of one geopolitics, geopolitical Legal entity, entity, usually in large numbers, entering territory (country subdivision), territory controlled by another similar entity, ...

which led to the capture of ʻUrabi and his allies and the imposition of British control in Egypt. ʻUrabi and his allies were sentenced by Tewfik into exile far away in British Ceylon

British Ceylon (; ), officially British Settlements and Territories in the Island of Ceylon with its Dependencies from 1802 to 1833, then the Island of Ceylon and its Territories and Dependencies from 1833 to 1931 and finally the Island of Cey ...

, as a form of punishment

Punishment, commonly, is the imposition of an undesirable or unpleasant outcome upon an individual or group, meted out by an authority—in contexts ranging from child discipline to criminal law—as a deterrent to a particular action or beh ...

.

Early life

He was born in 1841 in the village of Hirriyat Razna near Zagazig in the Sharqia Governorate, approximately 80 kilometres to the north ofCairo

Cairo ( ; , ) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Egypt and the Cairo Governorate, being home to more than 10 million people. It is also part of the List of urban agglomerations in Africa, largest urban agglomeration in Africa, L ...

. ʻUrabi was the son of a village leader and one of the wealthier members of the community, which allowed him to receive a decent education. After completing elementary education in his home village, he enrolled at Al-Azhar University

The Al-Azhar University ( ; , , ) is a public university in Cairo, Egypt. Associated with Al-Azhar Al-Sharif in Islamic Cairo, it is Egypt's oldest degree-granting university and is known as one of the most prestigious universities for Islamic ...

to complete his schooling in 1849. He entered the army and moved up quickly through the ranks, reaching lieutenant colonel by age 20. The modern education and military service of ʻUrabi, from a ''fellah

A fellah ( ; feminine ; plural ''fellaheen'' or ''fellahin'', , ) is a local peasant, usually a farmer or agricultural laborer in the Middle East and North Africa. The word derives from the Arabic word for "ploughman" or "tiller".

Due to a con ...

'', or peasant background, would not have been possible without the modernising reforms of Khedive Isma'il, who had done much to eliminate the barriers between the bulk of the Egyptian populace and the ruling elite, who were drawn largely from the military castes that had ruled Egypt for centuries. Isma'il abolished the exclusive access to the Egyptian and Sudanese military ranks by Egyptians of Balkan, Circassian, and Turkish origin. Isma'il conscripted soldiers and recruited students from throughout Egypt and Sudan regardless of class and ethnic backgrounds in order to form a "modern" and "national" Egyptian military and bureaucratic elite class. Without these reforms, ʻUrabi's rise through the ranks of the military would likely have been far more restricted.

ʻUrabi served during the Ethiopian-Egyptian War (1874-1876) in a support role on the Egyptian Army's lines of communication. He is said to have returned from the war - which Egypt lost - "incensed at the way in which it had been mismanaged", and the experience turned him towards politics and decisively against the Khedive.

Protest against Tewfik

He was a galvanizing speaker. Because of his peasant origins, he was at the time, and is still today, viewed as an authentic voice of the Egyptian people. Indeed, he was known by his followers as 'El Wahid' (the Only One), and when the British poet and explorer Wilfrid Blunt went to meet him, he found the entrance of ʻUrabi's house was blocked with supplicants. When Khedive Tewfik issued a new law preventing peasants from becoming officers, ʻUrabi led the group protesting the preference shown to aristocratic officers (again, largely Egyptians of foreign descent). ʻUrabi repeatedly condemned severe prevalent racial discrimination of ethnic Egyptians in the army.Thompson, Elizabeth. "Ahmad Urabi and Nazem al- Islam Kermani: Constitutional Justice in Egypt and Iran," ''Justice Interrupted'' (Harvard, 2013), 61–88. He and his followers, who included most of the army, were successful and the law was repealed. In 1879 they formed the Egyptian Nationalist Party in the hopes of fostering a stronger national identity. He and his allies in the army joined with the reformers in February 1882 to demand change. This revolt, also known as theʻUrabi revolt

The ʻUrabi revolt, also known as the ʻUrabi Revolution (), was a nationalist uprising in the Khedivate of Egypt from 1879 to 1882. It was led by and named for Colonel Ahmed Urabi and sought to depose the khedive, Tewfik Pasha, and end Imperial ...

, was primarily inspired by his desire for social justice for the Egyptians based on equal standing before the law. With the support of the peasants as well, he launched a broader effort to try to wrest Egypt and Sudan

Sudan, officially the Republic of the Sudan, is a country in Northeast Africa. It borders the Central African Republic to the southwest, Chad to the west, Libya to the northwest, Egypt to the north, the Red Sea to the east, Eritrea and Ethiopi ...

from foreign control, and also to end the absolutist regime of the Khedive, who was himself subject to European influence under the rules of the Caisse de la Dette Publique The Caisse de la Dette Publique ("Public Debt Commission", ) was an international commission established by a decree issued by Khedive Isma'il of Egypt on 2 May 1876 to supervise the payment by the Egyptian government of the loans to the European ...

. The Arab-Egyptian deputies demanded a constitution that granted the state parliamentary power. The revolt then spread to express resentment of the undue influence of foreigners, including the predominantly Turko- Circassian aristocracy from other parts of the Ottoman Empire.

Parliament planning

ʻUrabi was first promoted toBey

Bey, also spelled as Baig, Bayg, Beigh, Beig, Bek, Baeg, Begh, or Beg, is a Turkic title for a chieftain, and a royal, aristocratic title traditionally applied to people with special lineages to the leaders or rulers of variously sized areas in ...

, then made under-secretary of war, and ultimately a member of the cabinet. Plans were developed to create a parliamentary assembly. During the last months of the revolt (July to September 1882), it was claimed that ʻUrabi held the office of Prime Minister of the hastily created common law government based on popular sovereignty. Feeling threatened, Khedive Tewfik requested assistance against ʻUrabi from the Ottoman Sultan

The sultans of the Ottoman Empire (), who were all members of the Ottoman dynasty (House of Osman), ruled over the Boundaries between the continents, transcontinental empire from its perceived inception in 1299 to Dissolution of the Ottoman Em ...

, to whom Egypt and Sudan still owed technical fealty. The Sublime Porte

The Sublime Porte, also known as the Ottoman Porte or High Porte ( or ''Babıali''; ), was a synecdoche or metaphor used to refer collectively to the central government of the Ottoman Empire in Istanbul. It is particularly referred to the buildi ...

hesitated in responding to the request.

British intervention

The British were especially concerned that ʻUrabi would default on Egypt's massive debt and that he might try to gain control of the

The British were especially concerned that ʻUrabi would default on Egypt's massive debt and that he might try to gain control of the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal (; , ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, Indo-Mediterranean, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia (and by extension, the Sinai Peninsula from the rest ...

. Therefore, they and the French dispatched warships to Egypt to prevent such an eventuality from occurring. Tewfik fled to their protection, moving his court to Alexandria

Alexandria ( ; ) is the List of cities and towns in Egypt#Largest cities, second largest city in Egypt and the List of coastal settlements of the Mediterranean Sea, largest city on the Mediterranean coast. It lies at the western edge of the Nile ...

. The strong naval presence spurred fears of an imminent invasion (as had been the case in Tunisia in 1881) causing anti-Christian riots to break out in Alexandria

Alexandria ( ; ) is the List of cities and towns in Egypt#Largest cities, second largest city in Egypt and the List of coastal settlements of the Mediterranean Sea, largest city on the Mediterranean coast. It lies at the western edge of the Nile ...

on 12 June 1882. The French fleet was recalled to France, while the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

warships in the harbor opened fire on the city's artillery emplacements after the Egyptians ignored an ultimatum from Admiral Seymour to remove them.

The Battle of Kassassin was fought at the Sweet Water Canal, when on August 28, 1882, the British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

force was attacked by the Egyptians, led by 'Urabi. They needed to carve a passage through Ismailia

Ismailia ( ', ) is a city in north-eastern Egypt. Situated on the west bank of the Suez Canal, it is the capital of the Ismailia Governorate. The city had an estimated population of about 1,434,741 according to the statistics issued by the Cen ...

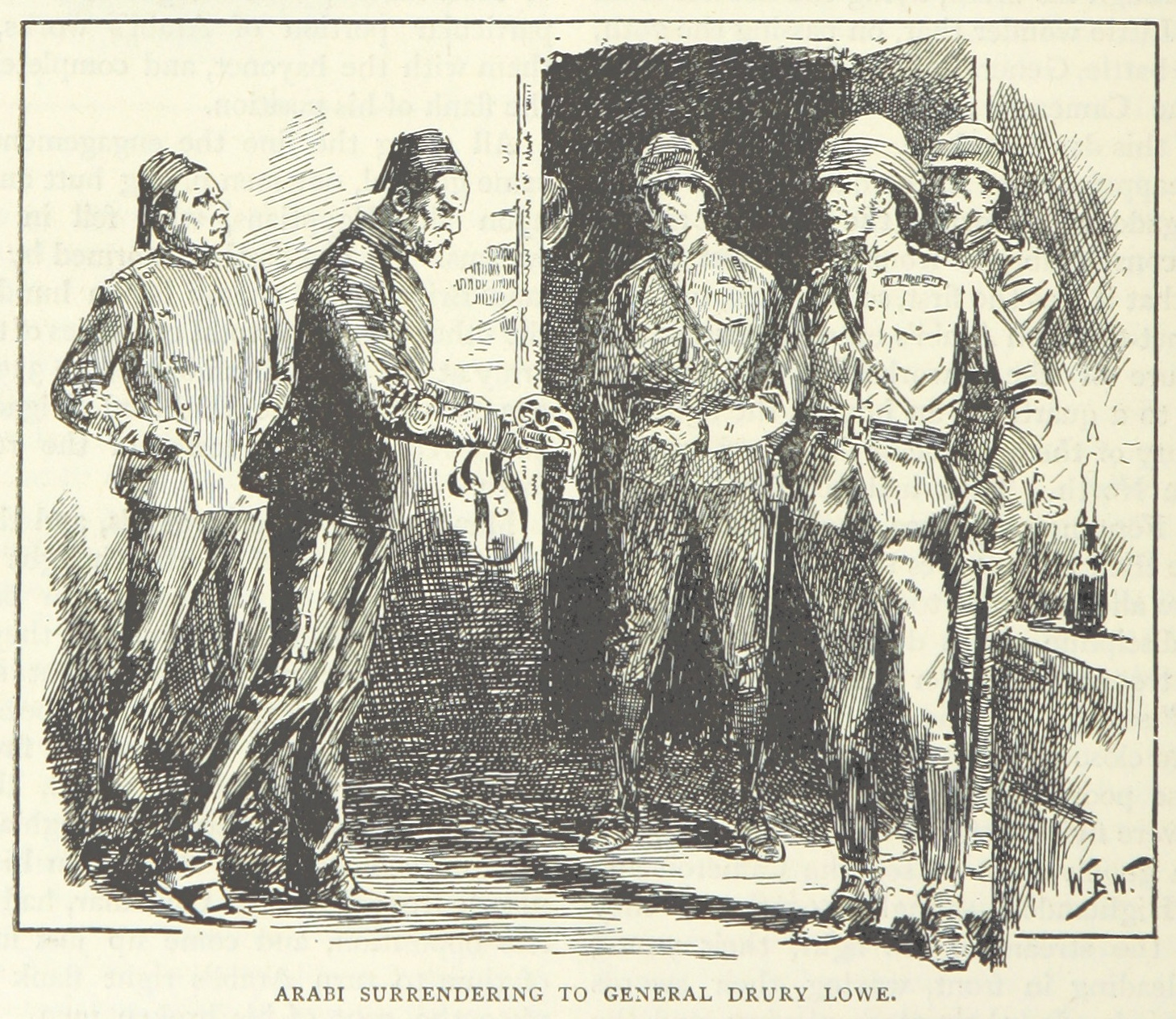

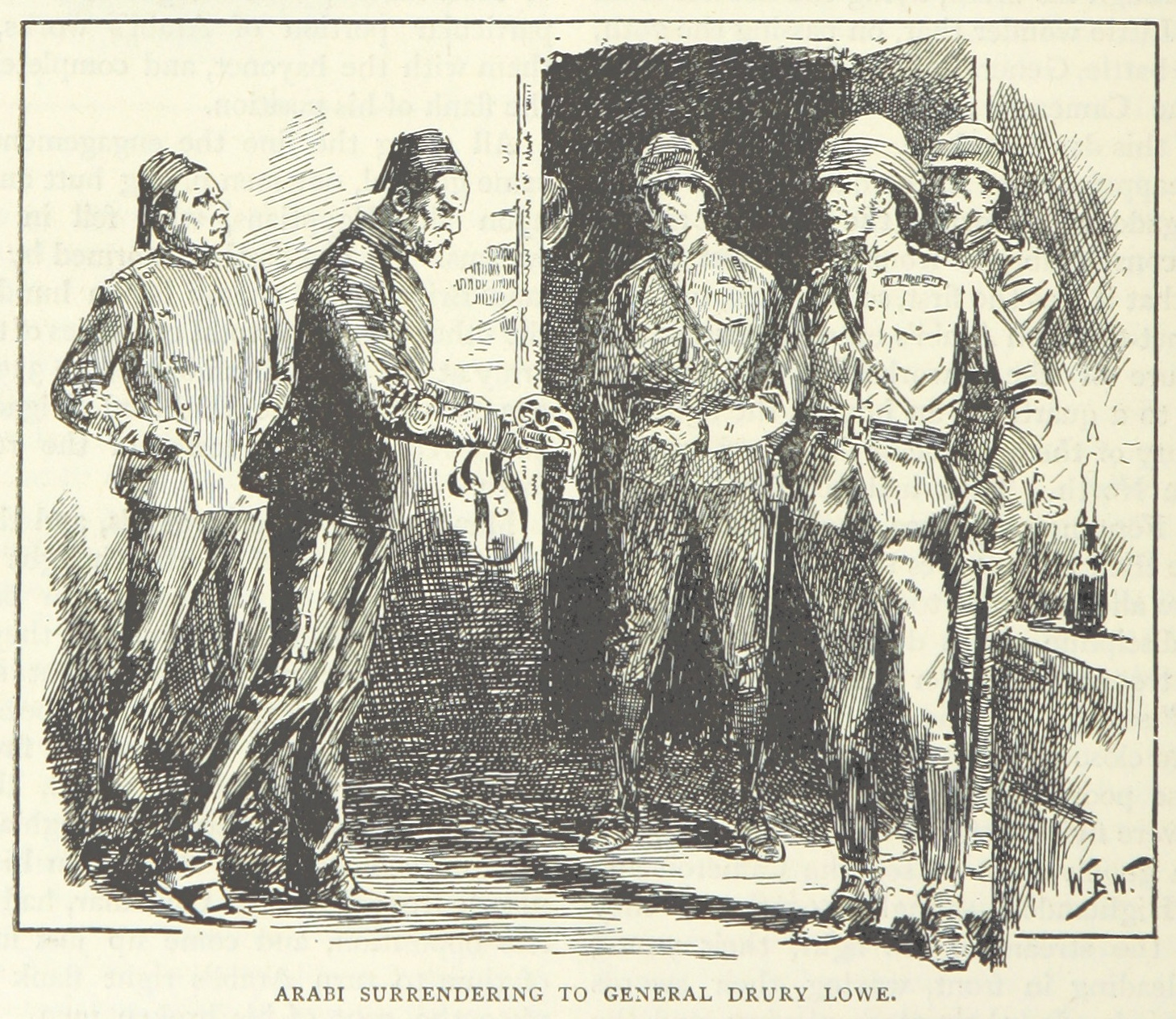

and the cultivated Delta. Both attacks were repulsed. The Household Cavalry under the command of General Drury Drury-Lowe led the "Moonlight Charge", consisting of the Royal Horse Guards and 7th Dragoon Guards

Dragoon Guards is a designation that has been used to refer to certain heavy cavalry regiments in the British Army since the 18th century. While the Prussian and Russian armies of the same period included dragoon regiments among their respective I ...

galloping at full tilt into enemy rifle fire. Their ranks were whittled down from the saddle, but still they charged headlong, ever forward. Sir Baker Russell commanded 7th on the right; whereas the Household was led by Colonel Ewart, c/o of the Life Guards. They captured 11 Egyptian guns. Despite only half a dozen casualties, Wolseley was so concerned about the quality of his men that he wrote Cambridge for reforms to recruiting. Nonetheless, these were the elite of the British army and, these skirmishes were costly. Legend and a poem "At Kassassin", say the battle began as it was getting dark.

On September 9, Urabi seized what he considered his last chance to attack the British position. A fierce battle ensued on the railway line at 7 am. General Willis sallied out from emplacements to drive back the Egyptians, who at 12 pm returned to their trenches. Thereupon Sir Garnet Wolseley arrived with the main force, while the Household Cavalry guarded his flank from a force at Salanieh. A total force of 634 officers and 16,767 NCOs and men were stationed at Kassassin before they marched on September 13, 1882, towards the main objective at Tell El Kebir where another battle was fought, the Battle of Tell El Kebir.

In September a British army landed in Alexandria but failed to reach Cairo after being checked at the Battle of Kafr El Dawwar. Another army, led by Sir Garnet Wolseley, landed in the Canal Zone and on 13 September 1882 they defeated ʻUrabi's army at the Battle of Tell El Kebir. From there, the British force advanced on Cairo which surrendered without a shot being fired, as did ʻUrabi and the other nationalist leaders.

Exile and return

ʻUrabi was tried by the restored Khedivate for rebellion on 3 December 1882. He was defended by British solicitorRichard Eve

Richard Eve Royal Geographical Society, FRGS (6 December 1831–7 July 1900) was a solicitor and notary in Aldershot in Hampshire in the 19th century and a prominent Freemasonry, Freemason who was the Grand Treasurer of the United Grand Lodg ...

and Alexander Meyrick Broadley. According to Elizabeth Thompson, ʻUrabi's defense stressed the idea that despite the fact that he had been illegally incarcerated by Riyad Pasha and the Khedive Tewfik he had still responded in a manner allowed under Egyptian law and with the hopes that the khedivate remain after his intervention, thus demonstrating loyalty to the Egyptian people as required by his duties. In accordance with an understanding made with the British representative, Lord Dufferin, ʻUrabi pleaded guilty and was sentenced to death, but the sentence was immediately commuted to one of banishment for life. He left Egypt on 28 December 1882 for Ceylon

Sri Lanka, officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, also known historically as Ceylon, is an island country in South Asia. It lies in the Indian Ocean, southwest of the Bay of Bengal, separated from the Indian subcontinent, ...

(now Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka, officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, also known historically as Ceylon, is an island country in South Asia. It lies in the Indian Ocean, southwest of the Bay of Bengal, separated from the Indian subcontinent, ...

). His home in Halloluwa Road, Kandy

Kandy (, ; , ) is a major city located in the Central Province, Sri Lanka, Central Province of Sri Lanka. It was the last capital of the Sinhalese monarchy from 1469 to 1818, under the Kingdom of Kandy. The city is situated in the midst of ...

(formerly owned by Mudaliyar Jeronis de Soysa) is now the Orabi Pasha Cultural Center. During his time in Ceylon, ʻUrabi worked to improve the quality of education amongst the Muslims in the country. Hameed Al Husseinie College, Sri Lanka's first school for Muslims was established on 15 November 1884 and after eight years Zahira College, was established on 22 August 1892 under his patronage. In May 1901, Khedive Abbas II, Tewfik's son and successor permitted ʻUrabi to return to Egypt. Abbas was a nationalist in the vein of his grandfather, Khedive Isma'il the Magnificent, and remained deeply opposed to British influence in Egypt. ʻUrabi returned on 1 October 1901, and remained in Egypt until his death on 21 September 1911.

Legacy

While the British intervention was meant to be a temporary state of affairs, British forces continued to occupy Egypt for decades afterwards. In 1914, fearing that the nationalist Khedive Abbas II would form an alliance with theOttoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

against the United Kingdom during the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, the British administration in Egypt deposed him in favour of his uncle, Hussein Kamel. The legal fiction of Ottoman sovereignty was terminated, and the Sultanate of Egypt that had been destroyed by the Ottomans in 1517 was re-established, with Hussein Kamel as Sultan

Sultan (; ', ) is a position with several historical meanings. Originally, it was an Arabic abstract noun meaning "strength", "authority", "rulership", derived from the verbal noun ', meaning "authority" or "power". Later, it came to be use ...

. No longer an Ottoman vassal state, Egypt was declared a British protectorate

British protectorates were protectorates under the jurisdiction of the British government. Many territories which became British protectorates already had local rulers with whom the Crown negotiated through treaty, acknowledging their status wh ...

. Five years later, nationalist opposition to the United Kingdom's continued dominance of Egyptian affairs sparked the Egyptian Revolution of 1919, prompting the British to formally recognise Egypt as an independent sovereign state in 1922.

ʻUrabi's revolt had a profound and long-lasting impact on Egypt, surpassing even the efforts of resistance hero Omar Makram in its significance as an expression of nationalistic sentiments in Egypt. It would later play a very important role in Egyptian history, with some historians noting that the 1881-1882 revolution laid the foundation for mass politics in Egypt. In July 1952, when Mohamed Naguib

Major General Mohamed Bey Naguib Youssef Qutb El-Qashlan (; 19 February 1901 – 28 August 1984), known simply as Mohamed Naguib (, ), was an Egyptian military officer and revolutionary who, along with Gamal Abdel Nasser, was one of the two prin ...

, one of the two principal leaders of the Egyptian Revolution of 1952

The Egyptian revolution of 1952, also known as the 1952 coup d'état () and the 23 July Revolution (), was a period of profound political, economic, and societal change in Egypt. On 23 July 1952, the revolution began with the toppling of King ...

, addressed crowds of supporters in Cairo's Ismailia Square on the toppling of King Farouk, he consciously linked this 20th century revolution to 'Urabi's revolt against the Egyptian monarch seven decades earlier, reciting 'Urabi's words to Khedive Tewfik that the people of Egypt were "no longer inheritable" by any ruler. The new revolutionary government mimicked 'Urabi in declaring that Ismailia Square, the main public plaza in Cairo, henceforth be Tahrir Square (''Liberation Square''). During the tenure of Gamal Abdel Nasser

Gamal Abdel Nasser Hussein (15 January 1918 – 28 September 1970) was an Egyptian military officer and revolutionary who served as the second president of Egypt from 1954 until his death in 1970. Nasser led the Egyptian revolution of 1952 a ...

, who led the Revolution with Naguib and succeeded him as Prime Minister and later President, ʻUrabi would be hailed as an Egyptian patriot and a national hero. He also inspired political activists living in Ceylon

Sri Lanka, officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, also known historically as Ceylon, is an island country in South Asia. It lies in the Indian Ocean, southwest of the Bay of Bengal, separated from the Indian subcontinent, ...

.

Tributes

Egypt

*Alexandria

Alexandria ( ; ) is the List of cities and towns in Egypt#Largest cities, second largest city in Egypt and the List of coastal settlements of the Mediterranean Sea, largest city on the Mediterranean coast. It lies at the western edge of the Nile ...

's Orabi Square

* Cairo

Cairo ( ; , ) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Egypt and the Cairo Governorate, being home to more than 10 million people. It is also part of the List of urban agglomerations in Africa, largest urban agglomeration in Africa, L ...

's Al Mohandessin district has a main street and its underground station named after him.

* Zagazig's main square contains an equestrian statue

An equestrian statue is a statue of a rider mounted on a horse, from the Latin ''eques'', meaning 'knight', deriving from ''equus'', meaning 'horse'. A statue of a riderless horse is strictly an equine statue. A full-sized equestrian statue is a ...

of ʻUrabi, and its university's emblem bears his picture

Abroad

* Arabi, Louisiana, a suburb ofNew Orleans

New Orleans (commonly known as NOLA or The Big Easy among other nicknames) is a Consolidated city-county, consolidated city-parish located along the Mississippi River in the U.S. state of Louisiana. With a population of 383,997 at the 2020 ...

, was named in honour of 'Urabi as the residents of the suburb felt a sense of solidarity with him due to the fact that they were a part of New Orleans which sought to separate from the city.

* The Gaza Strip

The Gaza Strip, also known simply as Gaza, is a small territory located on the eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea; it is the smaller of the two Palestinian territories, the other being the West Bank, that make up the State of Palestine. I ...

has a coastal road named Ahmed Orabi Street.

* Colombo

Colombo, ( ; , ; , ), is the executive and judicial capital and largest city of Sri Lanka by population. The Colombo metropolitan area is estimated to have a population of 5.6 million, and 752,993 within the municipal limits. It is the ...

, Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka, officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, also known historically as Ceylon, is an island country in South Asia. It lies in the Indian Ocean, southwest of the Bay of Bengal, separated from the Indian subcontinent, ...

, has an Orabi Pasha Street in its central district.

* Kandy

Kandy (, ; , ) is a major city located in the Central Province, Sri Lanka, Central Province of Sri Lanka. It was the last capital of the Sinhalese monarchy from 1469 to 1818, under the Kingdom of Kandy. The city is situated in the midst of ...

, Sri Lanka, is home to the Orabi Pasha Cultural Centre.

Quotes

* ''"How can you enslave people when their mothers bore them free?"''. The reference is: Once, a governor of Egypt punished a non-Muslim wrongly. The case was brought to the caliph of time (i.e. Umar ibn ul Khattab, the second Caliph of Islam) and the Muslim governor was proven to be wrong. Umar told the non-Muslim to punish the governor in same fashion, after it Umar said: Since when have you considered people as your slaves? Although their mothers gave birth to them as free living people.''Kanz ul Amaal'', Volume No. 4, Page No. 455 * ''"Allah has created us free, and did not make us into heritage or estate. So by Allah, the only god, we shall be bequeathed or enslaved no more"''Notes

* The earliest published work of Isabella Augusta, Lady Gregory – later to embraceIrish Nationalism

Irish nationalism is a nationalist political movement which, in its broadest sense, asserts that the people of Ireland should govern Ireland as a sovereign state. Since the mid-19th century, Irish nationalism has largely taken the form of cult ...

and have an important role in the cultural life of Ireland – was ''Arabi and His Household'' (1882), a pamphlet (originally a letter to ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British Newspaper#Daily, daily Newspaper#National, national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its modern name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its si ...

'' newspaper) in support of ʻUrabi.

References

Further reading

* Huffaker, Shauna. "Representations of Ahmed Urabi: Hegemony, Imperialism, and the British Press, 1881–1882." ''Victorian Periodicals Review'' 45.4 (2012): 375-405.External links

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Urabi, Ahmed 1841 births 1911 deaths Egyptian Muslims 19th-century prime ministers of Egypt 19th-century rebels Al-Azhar University alumni Defence ministers of Egypt Egyptian nationalists Egyptian soldiers Egyptian revolutionaries People from Zagazig People of the Urabi revolt Egyptian exiles People from Sharqia Governorate Egyptian prisoners sentenced to death Egyptian pashas Egyptian rebels Egyptian independence activists Prisoners sentenced to death by the United Kingdom