Agesilaus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Agesilaus II (; ; 445/4 – 360/59 BC) was king of

Agesilaus returned to Greece by land, crossing the

Agesilaus returned to Greece by land, crossing the

fro

Livius.Org

In 370 Agesilaus was engaged in an embassy to Mantineia, and reassured the Spartans with an invasion of Arcadia. He preserved an unwalled Sparta against the revolts and conspiracies of

Sometime after the Battle of Mantineia, Agesilaus went to

Sometime after the Battle of Mantineia, Agesilaus went to

Other historical accounts paint Agesilaus as a prototype for the ideal leader. His awareness, thoughtfulness, and wisdom were all traits to be emulated diplomatically, while his bravery and shrewdness in battle epitomised the heroic Greek commander. These historians point towards the unstable oligarchies established by Lysander in the former Athenian Empire and the failures of Spartan leaders (such as Pausanias and Kleombrotos) for the eventual suppression of Spartan power. The ancient historian

Other historical accounts paint Agesilaus as a prototype for the ideal leader. His awareness, thoughtfulness, and wisdom were all traits to be emulated diplomatically, while his bravery and shrewdness in battle epitomised the heroic Greek commander. These historians point towards the unstable oligarchies established by Lysander in the former Athenian Empire and the failures of Spartan leaders (such as Pausanias and Kleombrotos) for the eventual suppression of Spartan power. The ancient historian

Disability and Infanticide in Ancient Greece

, ''Hesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens'', Vol. 90, No. 4, 2021, pp. 747–772. * Maria Stamatopoulou,

Thessalians Abroad, the Case of Pharsalos

, in ''Mediterranean Historical Review'', vol. 22.2 (2007), pp. 211–236. *Graham Wylie, "Agesilaus and the Battle of Sardis", in ''Klio'', n°74 (1992), pp. 118–130. {{DEFAULTSORT:Agesilaus 02 440s BC births Year of birth uncertain 358 BC deaths Year of death uncertain 4th-century BC Spartans Eurypontid kings of Sparta Ancient Greek generals Spartan hegemony

Sparta

Sparta was a prominent city-state in Laconia in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (), while the name Sparta referred to its main settlement in the Evrotas Valley, valley of Evrotas (river), Evrotas rive ...

from 400 to 360 BC. Generally considered the most important king in the history of Sparta, Agesilaus was the main actor during the period of Spartan hegemony

Spartan hegemony refers to the period of dominance by Sparta in Greek affairs from 404 to 371 BC. Even before this period the polis of Sparta was the greatest Spartan army, military land power of classical Ancient Greece, Greek antiquity and govern ...

that followed the Peloponnesian War

The Second Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC), often called simply the Peloponnesian War (), was an Ancient Greece, ancient Greek war fought between Classical Athens, Athens and Sparta and their respective allies for the hegemony of the Ancien ...

(431–404 BC). Although brave in combat, Agesilaus lacked the diplomatic skills to preserve Sparta's position, especially against the rising power of Thebes, which reduced Sparta to a secondary power after its victory at Leuctra in 371 BC.

Despite the traditional secrecy fostered by the Spartiates, the reign of Agesilaus is particularly well-known thanks to the works of his friend Xenophon

Xenophon of Athens (; ; 355/354 BC) was a Greek military leader, philosopher, and historian. At the age of 30, he was elected as one of the leaders of the retreating Ancient Greek mercenaries, Greek mercenaries, the Ten Thousand, who had been ...

, who wrote a large history of Greece (the ''Hellenica

''Hellenica'' () simply means writings on Greek (Hellenic) subjects. Several histories of the 4th-century BC Greece have borne the conventional Latin title ''Hellenica'', of which very few survive.Murray, Oswyn, "Greek Historians", in John Boardma ...

'') covering the years 411 to 362 BC, therefore extensively dealing with Agesilaus' rule. Xenophon furthermore composed a panegyric biography of his friend, perhaps to clean his memory from the criticisms voiced against him. Another historical tradition—much more hostile to Agesilaus than Xenophon's writings—has been preserved in the ''Hellenica Oxyrhynchia

''Hellenica Oxyrhynchia'' is an Ancient Greek history of Greece in the late 5th and early 4th centuries BCE known only from papyrus fragments unearthed at Oxyrhynchus in Egypt. The author, whose name is not recorded in the surviving fragments, is ...

'', and later continued by Diodorus of Sicily

Diodorus Siculus or Diodorus of Sicily (; 1st century BC) was an ancient Greek historian from Sicily. He is known for writing the monumental universal history ''Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which survive intact, bet ...

. Moreover, Plutarch

Plutarch (; , ''Ploútarchos'', ; – 120s) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo (Delphi), Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''Parallel Lives'', ...

wrote a biography of Agesilaus in his ''Parallel Lives

*

Culture of ancient Greece

Culture of ancient Rome

Ancient Greek biographical works

Ethics literature

History books about ancient Rome

Cultural depictions of Gaius Marius

Cultural depictions of Mark Antony

Cultural depictions of Cicero

...

'', which contains many elements deliberately omitted by Xenophon.

Early life

Youth

Agesilaus' father was KingArchidamos II

Archidamus II ( ; died 427/6 BC) was a king of Sparta who reigned from approximately 469/8 BC to 427/6 BC. His father was Zeuxidamus (called Cyniscos by many Spartans). Zeuxidamus married and had a son, Archidamus. However, Zeuxidamus di ...

(r. 469–427), who belonged to the Eurypontid dynasty, one of the two royal families of Sparta. Archidamos already had a son from a first marriage with Lampito (his own step-aunt) named Agis Agis or AGIS may refer to:

People

* Agis I (died 900 BC), Spartan king

* Agis II (died 401 BC), Spartan king

* Agis III (died 331 BC), Spartan king

* Agis IV (265–241 BC), Spartan king

* Agis (Paeonian) (died 358 BC), King of the Paeonians

* Ag ...

. After the death of Lampito, Archidamos remarried in the early 440s with Eupolia, daughter of Melesippidas, whose name indicates an aristocratic status. The dates of Agesilaus' birth, death, and reign are disputed. The only secured information is that he was 84 at his death. The majority opinion is to date his birth to 445/4, but a minority of scholars move it a bit later, c.442. Most of the other dates of Agesilaus are similarly disputed, with the minority moving them about two years later than the majority. Agesilaus also had a sister named Kyniska (the first woman in ancient history to achieve an Olympic victory). The name Agesilaus was rare and harks back to Agesilaus I, one of the earliest kings of Sparta.

Agesilaus was born lame, a fact that should have cost him his life, since in Sparta deformed babies were thrown into a chasm. As he was not heir-apparent, he might have received some leniency from the tribal elders who examined male infants, or perhaps the first effects of the demographic decline of Sparta were already felt at the time, and only the most severely impaired babies were killed.

Starting at the age of 7, Agesilaus had to go through the rigorous education system of Sparta, called the '' agoge''. Despite his disability, he brilliantly completed the training,Hamilton, ''Agesilaus'', p. 14. which massively enhanced his prestige, especially after he became king. Indeed, as heirs-apparent were exempted of the ''agoge'', few Spartan kings had gone through the same training as the citizens; another notable exception was Leonidas, the embodiment of the "hero-king". Between 433 and 428, Agesilaus also became the younger lover of Lysander

Lysander (; ; 454 BC – 395 BC) was a Spartan military and political leader. He destroyed the Athenian fleet at the Battle of Aegospotami in 405 BC, forcing Athens to capitulate and bringing the Peloponnesian War to an end. He then played ...

, an aristocrat from the circle of Archidamos, whose family had some influence in Libya.

Spartan prince

Little is known of Agesilaus' adult life before his reign, principally becauseXenophon

Xenophon of Athens (; ; 355/354 BC) was a Greek military leader, philosopher, and historian. At the age of 30, he was elected as one of the leaders of the retreating Ancient Greek mercenaries, Greek mercenaries, the Ten Thousand, who had been ...

—his friend and main biographer—only wrote about his reign. Due to his special status, Agesilaus likely became a member of the Krypteia, an elite corps of young Spartans going undercover in Spartan territory to kill some helots

The helots (; , ''heílotes'') were a subjugated population that constituted a majority of the population of Laconia and Messenia – the territories ruled by Sparta. There has been controversy since antiquity as to their exact characteristic ...

deemed dangerous. Once he turned 20 and became a full citizen, Agesilaus was elected to a common mess, presumably that of his elder half-brother Agis II, who had become king in 427, of which Lysander was perhaps a member.

Agesilaus probably served during the Peloponnesian War

The Second Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC), often called simply the Peloponnesian War (), was an Ancient Greece, ancient Greek war fought between Classical Athens, Athens and Sparta and their respective allies for the hegemony of the Ancien ...

(431–404) against Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

, likely at the Battle of Mantinea in 418. Agesilaus married Kleora at some point between 408 and 400. Despite the influence she apparently had on her husband, she is mostly unknown. Her father was Aristomenidas, an influential noble with connections in Thebes.

Thanks to three treaties signed with Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

in 412–411, Sparta received funding from the Persians, which it used to build a fleet that ultimately defeated Athens. This fleet was essentially led by Lysander, whose success gave him an enormous influence in the Greek cities of Asia as well as in Sparta, where he even schemed to become king. In 403 the two kings, Agis and Pausanias, acted together to relieve him from his command.

Reign

Accession to the throne (400–398 BC)

Agis II died while returning fromDelphi

Delphi (; ), in legend previously called Pytho (Πυθώ), was an ancient sacred precinct and the seat of Pythia, the major oracle who was consulted about important decisions throughout the ancient Classical antiquity, classical world. The A ...

between 400 and 398. After his funeral, Agesilaus contested the claim of Leotychidas, the son of Agis II, using the widespread belief in Sparta that Leotychidas was an illegitimate son of Alcibiades

Alcibiades (; 450–404 BC) was an Athenian statesman and general. The last of the Alcmaeonidae, he played a major role in the second half of the Peloponnesian War as a strategic advisor, military commander, and politician, but subsequently ...

—a famous Athenian statesman and nephew of Pericles

Pericles (; ; –429 BC) was a Greek statesman and general during the Golden Age of Athens. He was prominent and influential in Ancient Athenian politics, particularly between the Greco-Persian Wars and the Peloponnesian War, and was acclaimed ...

, who had gone into exile in Sparta during the Peloponnesian War, and then seduced the queen. The rumours were strengthened by the fact that even Agis only recognised Leotychidas as his son on his deathbed.

Diopeithes, a supporter of Leotychidas, however quoted an old oracle telling that a Spartan king could not be lame, thus refuting Agesilaus' claim, but Lysander cunningly returned the objection by saying that the oracle had to be understood figuratively. The lameness warned against by the oracle would therefore refer to the doubt on Leotychidas' paternity, and this reasoning won the argument. The role of Lysander in the accession of Agesilaus has been debated among historians, principally because Plutarch

Plutarch (; , ''Ploútarchos'', ; – 120s) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo (Delphi), Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''Parallel Lives'', ...

makes him the main instigator of the plot, while Xenophon downplays Lysander's influence. Lysander doubtless supported Agesilaus' accession because he hoped that the new king would in return help him to regain the importance that he lost in 403.

Conspiracy of Cinadon (399 BC)

The Conspiracy of Cinadon took place during the first year of Agesilaus' reign, in the summer of 399. Cinadon was a '' hypomeion'', a Spartan who had lost his citizen status, presumably because he could not afford the price of the collective mess—one of the main reasons for the dwindling number of Spartan citizens in theClassical Era

Classical antiquity, also known as the classical era, classical period, classical age, or simply antiquity, is the period of cultural European history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD comprising the interwoven civilization ...

, called '' oliganthropia''. It is probable that the vast influx of wealth coming to the city after its victory against Athens in 404 triggered inflation in Sparta, which impoverished many citizens with a fixed income, like Cinadon, and caused their downgrade. Therefore, the purpose of the plot was likely to restore the status of these disfranchised citizens. However, the plot was uncovered and Cinadon and its leaders executed—probably with the active participation of Agesilaus, but no further action was taken to solve the social crisis at the origin of the conspiracy. The failure of Agesilaus to acknowledge the critical problem suffered by Sparta at the time has been criticised by modern historians.

Invasion of Asia Minor (396–394 BC)

According to the treaties signed in 412 and 411 between Sparta and the Persian Empire, the latter became the overlord of the Greek city-states ofAsia Minor

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

.Hamilton, ''Sparta's Bitter Victories'', p. 27. In 401, these cities and Sparta supported the bid of Cyrus the Younger

Cyrus the Younger ( ''Kūruš''; ; died 401 BC) was an Achaemenid prince and general. He ruled as satrap of Lydia and Ionia from 408 to 401 BC. Son of Darius II and Parysatis, he died in 401 BC in battle during a failed attempt to oust his ...

(the Persian Emperor's younger son and a good friend of Lysander) against his elder brother, the new emperor Artaxerxes II

Arses (; 445 – 359/8 BC), known by his regnal name Artaxerxes II ( ; ), was King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire from 405/4 BC to 358 BC. He was the son and successor of Darius II () and his mother was Parysatis.

Soon after his accession, Ar ...

, who nevertheless defeated Cyrus at Cunaxa. As a result, Sparta remained at war with Artaxerxes, and supported the Greek cities of Asia, which fought against Tissaphernes

Tissaphernes (; ; , ; 445395 BC) was a Persian commander and statesman, Satrap of Lydia and Ionia. His life is mostly known from the works of Thucydides and Xenophon. According to Ctesias, he was the son of Hidarnes III and therefore, the gre ...

, the satrap

A satrap () was a governor of the provinces of the ancient Median kingdom, Median and Achaemenid Empire, Persian (Achaemenid) Empires and in several of their successors, such as in the Sasanian Empire and the Hellenistic period, Hellenistic empi ...

of Lydia

Lydia (; ) was an Iron Age Monarchy, kingdom situated in western Anatolia, in modern-day Turkey. Later, it became an important province of the Achaemenid Empire and then the Roman Empire. Its capital was Sardis.

At some point before 800 BC, ...

and Caria

Caria (; from Greek language, Greek: Καρία, ''Karia''; ) was a region of western Anatolia extending along the coast from mid-Ionia (Mycale) south to Lycia and east to Phrygia. The Carians were described by Herodotus as being Anatolian main ...

. In 397 Lysander engineered a large expedition in Asia headed by Agesilaus, likely to recover the influence he had over the Asian cities at the end of the Peloponnesian War. In order to win the approval of the Spartan assembly, Lysander built an army with only 30 Spartiates (full Spartan citizens), so the risk would be limited; the bulk of the army consisted of 2,000 neodamodes (freed helots

The helots (; , ''heílotes'') were a subjugated population that constituted a majority of the population of Laconia and Messenia – the territories ruled by Sparta. There has been controversy since antiquity as to their exact characteristic ...

) and 6,000 Greek allies. In addition, Agesilaus obtained the support of the oracles of Zeus

Zeus (, ) is the chief deity of the List of Greek deities, Greek pantheon. He is a sky father, sky and thunder god in ancient Greek religion and Greek mythology, mythology, who rules as king of the gods on Mount Olympus.

Zeus is the child ...

at Olympia and Apollo

Apollo is one of the Twelve Olympians, Olympian deities in Ancient Greek religion, ancient Greek and Ancient Roman religion, Roman religion and Greek mythology, Greek and Roman mythology. Apollo has been recognized as a god of archery, mu ...

at Delphi

Delphi (; ), in legend previously called Pytho (Πυθώ), was an ancient sacred precinct and the seat of Pythia, the major oracle who was consulted about important decisions throughout the ancient Classical antiquity, classical world. The A ...

.

The sacrifice at Aulis (396 BC)

Lysander and Agesilaus had intended the expedition to be a Panhellenic enterprise, but Athens,Corinth

Corinth ( ; , ) is a municipality in Corinthia in Greece. The successor to the ancient Corinth, ancient city of Corinth, it is a former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese (region), Peloponnese, which is located in south-central Greece. Sin ...

, and especially Thebes, refused to participate. In Spring 396, Agesilaus came to Aulis (in Boeotia

Boeotia ( ), sometimes Latinisation of names, Latinized as Boiotia or Beotia (; modern Greek, modern: ; ancient Greek, ancient: ), is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the modern regions of Greece, region of Central Greece (adm ...

n territory) to sacrifice on the place where Agamemnon

In Greek mythology, Agamemnon (; ''Agamémnōn'') was a king of Mycenae who commanded the Achaeans (Homer), Achaeans during the Trojan War. He was the son (or grandson) of King Atreus and Queen Aerope, the brother of Menelaus, the husband of C ...

had done so just before his departure to Troy

Troy (/; ; ) or Ilion (; ) was an ancient city located in present-day Hisarlik, Turkey. It is best known as the setting for the Greek mythology, Greek myth of the Trojan War. The archaeological site is open to the public as a tourist destina ...

at the head of the Greek army in the ''Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; , ; ) is one of two major Ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the ''Odyssey'', the poem is divided into 24 books and ...

'', thus giving a grandiose aspect to the expedition. However he did not inform the Boeotians and brought his own seer to perform the sacrifice, instead of the local one. Learning this, the Boeotians prevented him from sacrificing and further humiliated him by casting away the victim; they perhaps intended to provoke a confrontation, as the relations between Sparta and Thebes had become execrable. Agesilaus then left to Asia, but Thebes remained hateful to him for the rest of his life.

Campaign in Asia (396–394 BC)

Once Agesilaus landed inEphesus

Ephesus (; ; ; may ultimately derive from ) was an Ancient Greece, ancient Greek city on the coast of Ionia, in present-day Selçuk in İzmir Province, Turkey. It was built in the 10th century BC on the site of Apasa, the former Arzawan capital ...

, the Spartan main base, he concluded a three months' truce with Tissaphernes, likely to settle the affairs among the Greek allies. He integrated some of the Greek mercenaries formerly hired by Cyrus the Younger (the Ten Thousand

The Ten Thousand (, ''hoi Myrioi'') were a force of mercenary units, mainly Greeks, employed by Cyrus the Younger to attempt to wrest the throne of the Persian Empire from his brother, Artaxerxes II. Their march to the Battle of Cunaxa and bac ...

) in his army. They had returned from Persia under the leadership of Xenophon, who also remained in Agesilaus' staff. In Ephesus, Agesilaus' authority was nevertheless overshadowed by Lysander, who was reacquainted with many of his supporters, men he had placed in control of the Greek cities at the end of the Peloponnesian War. Angered by his local aura, Agesilaus humiliated Lysander several times to force him to leave the army, despite his former relationship and Lysander's role in his accession to the throne. Plutarch adds that after Agesilaus' emancipation from him, Lysander returned to his undercover scheme to make the monarchy elective.

After Lysander's departure, Agesilaus raided Phrygia

In classical antiquity, Phrygia ( ; , ''Phrygía'') was a kingdom in the west-central part of Anatolia, in what is now Asian Turkey, centered on the Sangarios River.

Stories of the heroic age of Greek mythology tell of several legendary Ph ...

, the satrapy of Pharnabazus, until his advance guard was defeated not far from Daskyleion by the superior Persian cavalry. He then wintered at Ephesus, where he trained a cavalry force, perhaps on the advice of Xenophon, who had commanded the cavalry of the Ten Thousand. In 395, the Spartan king managed to trick Tissaphernes into thinking that he would attack Caria

Caria (; from Greek language, Greek: Καρία, ''Karia''; ) was a region of western Anatolia extending along the coast from mid-Ionia (Mycale) south to Lycia and east to Phrygia. The Carians were described by Herodotus as being Anatolian main ...

, in the south of Asia Minor, forcing the satrap to hold a defence line on the Meander river. Instead, Agesilaus moved north to the important city of Sardis

Sardis ( ) or Sardes ( ; Lydian language, Lydian: , romanized: ; ; ) was an ancient city best known as the capital of the Lydian Empire. After the fall of the Lydian Empire, it became the capital of the Achaemenid Empire, Persian Lydia (satrapy) ...

. Tissaphernes hastened to meet the king there, but his cavalry sent in advance was defeated by Agesilaus' army. After his victory at the Battle of Sardis, Agesilaus became the first king to be given the command of both land and sea.Cartledge, ''Sparta and Lakonia'', p. 237. He delegated the naval command to his brother-in-law Peisander, whom he appointed navarch despite his inexperience; perhaps Agesilaus wanted to avoid the rise of a new Lysander, who owed his prominence to his time as navarch. After his defeat, Tissaphernes was executed and replaced as satrap by Tithraustes

Tithraustes (Old Persian: ; Ancient Greek: ) was the Persian satrap of Sardis for several years in the early 4th century BC. Due to scanty historical records, little is known of the man or his activities. He was sent out from Susa to replace ...

, who gave Agesilaus 30 talents to move north to the satrapy of Pharnabazus (Persian satraps were often bitter rivals). Augesilaus' Phrygian campaign of 394 was fruitless, as he lacked the siege equipment required to take the fortresses of Leonton Kephalai, Gordion, and Miletou Teichos.Cartledge, ''Agesilaos'', p. 217.Xenophon tells that Agesilaus then wanted to campaign further east in Asia and sow discontent among the subjects of the Achaemenid empire, or even to conquer Asia. Plutarch went further and wrote that Agesilaus had prepared an expedition to the heart of Persia, up to her capital of Susa

Susa ( ) was an ancient city in the lower Zagros Mountains about east of the Tigris, between the Karkheh River, Karkheh and Dez River, Dez Rivers in Iran. One of the most important cities of the Ancient Near East, Susa served as the capital o ...

, thus making him a forerunner of Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon (; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), most commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip ...

. It is very unlikely that Agesilaus really had such a grand campaign in mind; regardless, he was soon forced to return to Europe in 394.

Corinthian War (395–387 BC)

Although Thebes and Corinth had been allies of Sparta throughout the Peloponnesian War, they were dissatisfied by the settlement of the war in 404, with Sparta as leader of the Greek world. Sparta's imperialist expansion in the Aegean greatly upset its former allies, notably by establishing friendly regimes and garrisons in smaller cities. Through large gifts, Tithraustes also encouraged Sparta's former allies to start a war in order to force the recall of Agesilaus from Asia—even though the influence of Persian gold has been exaggerated. The initiative came from Thebes, which provoked a war between their allyOzolian Locris

Ozolian Locris () or Hesperian Locris () was a region in Ancient Greece, inhabited by the Ozolian Locrians (; ) a tribe of the Locrians, upon the Corinthian Gulf, bounded on the north by Doris, on the east by Phocis, and on the west by Aetolia. ...

and Phocis

Phocis (; ; ) is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the administrative region of Central Greece. It stretches from the western mountainsides of Parnassus on the east to the mountain range of Vardousia on the west, upon the Gu ...

in order to bring Sparta to the latter's defence. Lysander and the other king Pausanias entered Boeotia, which enabled the Thebans to bring Athens in the war. Lysander then besieged Haliartus without waiting for Pausanias and was killed in a Boeotian counter-attack. In Sparta, Pausanias was condemned to death by Lysander's friends and went into exile.Xenophon

Xenophon of Athens (; ; 355/354 BC) was a Greek military leader, philosopher, and historian. At the age of 30, he was elected as one of the leaders of the retreating Ancient Greek mercenaries, Greek mercenaries, the Ten Thousand, who had been ...

, ''Hell.'' iii. 3, to the end, ''Agesilaus'' After its success at Haliartus, Thebes was able to build a coalition against Sparta, with notably Argos and Corinth, where a war council was established, and securing the defection of most of the cities of northern and central Greece. Unable to wage war on two fronts and with the loss of Lysander and Pausanias, Sparta had no choice but to recall Agesilaus from Asia. The Asian Greeks fighting for him said they wanted to continue serving with him, while Agesilaus promised he would return to Asia as soon as he could.

Agesilaus returned to Greece by land, crossing the

Agesilaus returned to Greece by land, crossing the Hellespont

The Dardanelles ( ; ; ), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli (after the Gallipoli peninsula) and in classical antiquity as the Hellespont ( ; ), is a narrow, natural strait and internationally significant waterway in northwestern Turkey t ...

and from there along the coast of the Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It is located between the Balkans and Anatolia, and covers an area of some . In the north, the Aegean is connected to the Marmara Sea, which in turn con ...

. In Thessaly

Thessaly ( ; ; ancient Aeolic Greek#Thessalian, Thessalian: , ) is a traditional geographic regions of Greece, geographic and modern administrative regions of Greece, administrative region of Greece, comprising most of the ancient Thessaly, a ...

he won a cavalry battle near Narthacium against the Pharsalians who had made an alliance with Thebes. He then entered Boeotia

Boeotia ( ), sometimes Latinisation of names, Latinized as Boiotia or Beotia (; modern Greek, modern: ; ancient Greek, ancient: ), is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the modern regions of Greece, region of Central Greece (adm ...

by the Thermopylae

Thermopylae (; ; Ancient: , Katharevousa: ; ; "hot gates") is a narrow pass and modern town in Lamia (city), Lamia, Phthiotis, Greece. It derives its name from its Mineral spring, hot sulphur springs."Thermopylae" in: S. Hornblower & A. Spaw ...

, where he received reinforcements from Sparta. Meanwhile, Aristodamos—the regent of the young Agiad king Agesipolis—won a major victory

The term victory (from ) originally applied to warfare, and denotes success achieved in personal duel, combat, after military operations in general or, by extension, in any competition. Success in a military campaign constitutes a strategic vi ...

at Nemea

Nemea (; ; ) is an ancient site in the northeastern part of the Peloponnese, in Greece. Formerly part of the territory of Cleonae (Argolis), Cleonae in ancient Argolis, it is today situated in the regional units of Greece, regional unit of Corin ...

near Argos, which was offset by the disaster of the Spartan navy at Cnidus

Knidos or Cnidus (; , , , Knídos) was a Ancient Greece, Greek city in ancient Caria and part of the Dorian Hexapolis, in south-western Asia Minor, modern-day Turkey. It was situated on the Datça peninsula, which forms the southern side of the ...

against the Persian fleet led by Conon, an exiled Athenian general. Agesilaus lied to his men about the outcome of the battle of Knidos to avoid demoralising them as they were about to fight a large engagement against the combined armies of Thebes, Athens, Argos and Corinth. The following Battle of Coronea was a classic clash between two lines of hoplites. The anti-Spartan allies were rapidly defeated, but the Thebans managed to retreat in good order, despite Agesilaus' activity on the front line, which caused him several injuries. The next day the Thebans requested a truce to recover their dead, therefore conceding defeat, although they had not been bested on the battlefield.Hamilton, ''Agesilaus'', p. 108. Agesilaus appears to have tried to win an honourable victory, by risking his life and being merciful with some Thebans who had sought shelter in the nearby Temple of Athena Itonia. He then moved to Delphi, where he offered one tenth of the booty he had amassed since his landing at Ephesus, and returned to Sparta.

No pitched battle took place in Greece in 393. Perhaps Agesilaus was still recovering from his wounds, or he was deprived of command because of the opposition of Lysander's and Pausanias' friends, who were disappointed by his lack of decisive victory and his appointment of Peisander as navarch before the disaster of Knidos. The loss of the Spartan fleet besides allowed Konon to capture the island of Kythera

Kythira ( ; ), also transliterated as Cythera, Kythera and Kithira, is an Greek islands, island in Greece lying opposite the south-eastern tip of the Peloponnese peninsula. It is traditionally listed as one of the seven main Ionian Islands, altho ...

, in the south of the Peloponnese, from where he could raid Spartan territory.Françoise Ruzé, "The Empire of the Spartans (404–371)", p. 336. In 392, Sparta sent Antalcidas to Asia in order to negotiate a general peace with Tiribazus, the satrap of Lydia

Lydia (; ) was an Iron Age Monarchy, kingdom situated in western Anatolia, in modern-day Turkey. Later, it became an important province of the Achaemenid Empire and then the Roman Empire. Its capital was Sardis.

At some point before 800 BC, ...

, while Sparta would recognise Persia's sovereignty over the Asian Greek cities. However, the Greek allies also sent emissaries to Sardis to refuse Antalcidas' plan, and Artaxerxes likewise rejected it. A second peace conference in Sparta failed the following year because of Athens. A personal enemy of Antalcidas, Agesilaus likely disapproved these talks, which show that his influence at home had waned. Plutarch says that he befriended the young Agiad king Agesipolis, possibly to prevent his opponents from coalescing behind him.

By 391 Agesilaus had apparently recovered his influence as he was appointed at the head of the army, while his half-brother Teleutias became navarch. The target was Argos, which had absorbed Corinth into a political union the previous year. In 390 BC he made several successful expeditions into Corinthian territory, capturing Lechaeum and Peiraion. The loss, however, of a battalion ( mora), destroyed by Iphicrates, neutralised these successes, and Agesilaus returned to Sparta. In 389 BC he conducted a campaign in Acarnania

Acarnania () is a region of west-central Greece that lies along the Ionian Sea, west of Aetolia, with the Achelous River for a boundary, and north of the gulf of Calydon, which is the entrance to the Gulf of Corinth. Today it forms the western part ...

, but two years later the Peace of Antalcidas

The King's Peace (387 BC) was a peace treaty guaranteed by the Persian King Artaxerxes II that ended the Corinthian War in ancient Greece. The treaty is also known as the Peace of Antalcidas, after Antalcidas, the Spartan diplomat who traveled to ...

, warmly supported by Agesilaus, put an end to the war, maintaining Spartan hegemony over Greece and returning the Greek cities of Asia Minor

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

to the Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire, also known as the Persian Empire or First Persian Empire (; , , ), was an Iranian peoples, Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great of the Achaemenid dynasty in 550 BC. Based in modern-day Iran, i ...

. In this interval, Agesilaus declined command over Sparta's aggression on Mantineia, and justified Phoebidas' seizure of the Theban Cadmea so long as the outcome provided glory to Sparta.

Decline

When war broke out afresh with Thebes, Agesilaus twice invadedBoeotia

Boeotia ( ), sometimes Latinisation of names, Latinized as Boiotia or Beotia (; modern Greek, modern: ; ancient Greek, ancient: ), is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the modern regions of Greece, region of Central Greece (adm ...

(in 378 and 377 BC), although he spent the next five years largely out of action due to an unspecified but apparently grave illness. In the congress of 371 an altercation is recorded between him and the Theban general Epaminondas

Epaminondas (; ; 419/411–362 BC) was a Greeks, Greek general and statesman of the 4th century BC who transformed the Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek polis, city-state of Thebes, Greece, Thebes, leading it out of Spartan subjugation into a pre ...

, and due to his influence, Thebes was peremptorily excluded from the peace, and orders given for Agesilaus's royal colleague Cleombrotus to march against Thebes in 371. Cleombrotus was defeated and killed at the Battle of Leuctra

The Battle of Leuctra (, ) was fought on 6 July 371 BC between the Boeotians led by the Thebes (Greece), Thebans, and the History of Sparta, Spartans along with their allies amidst the post–Corinthian War conflict. The battle took place in the ...

and the Spartan supremacy overthrown.Agesilausfro

Livius.Org

In 370 Agesilaus was engaged in an embassy to Mantineia, and reassured the Spartans with an invasion of Arcadia. He preserved an unwalled Sparta against the revolts and conspiracies of

helot

The helots (; , ''heílotes'') were a subjugated population that constituted a majority of the population of Laconia and Messenia – the territories ruled by Sparta. There has been controversy since antiquity as to their exact characteristics ...

s, perioeci

The Perioeci or Perioikoi (, ) were the second-tier citizens of the ''polis'' of Sparta until 200 BC. They lived in several dozen cities within Spartan territories (mostly Laconia and Messenia), which were dependent on Sparta. The ''perioeci'' ...

and even other Spartans; and against external enemies, with four different armies led by Epaminondas

Epaminondas (; ; 419/411–362 BC) was a Greeks, Greek general and statesman of the 4th century BC who transformed the Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek polis, city-state of Thebes, Greece, Thebes, leading it out of Spartan subjugation into a pre ...

penetrating Laconia

Laconia or Lakonia (, , ) is a historical and Administrative regions of Greece, administrative region of Greece located on the southeastern part of the Peloponnese peninsula. Its administrative capital is Sparti (municipality), Sparta. The word ...

that same year.

Asia Minor expedition (366 BC)

In 366 BC, Sparta and Athens, dissatisfied with the Persian king's support of Thebes following the embassy of Philiscus of Abydos, decided to provide careful military support to the opponents of the Achaemenid king. Athens and Sparta provided support for the revolting satraps in theRevolt of the Satraps

The Great Satraps' Revolt, or the Revolts of the Satraps (c. 370-c.360 BCE), was a rebellion in the Achaemenid Empire of several satraps in western Anatolia against the authority of the Great King Artaxerxes II (r. 404-359/8). The Satraps who revo ...

, in particular Ariobarzanes: Sparta sent a force to Ariobarzanes under an aging Agesilaus, while Athens sent a force under Timotheus, which was however diverted when it became obvious that Ariobarzanes had entered frontal conflict with the Achaemenid king. An Athenian mercenary force under Chabrias

Chabrias (; bef. 420–357 BC) was an Athens, Athenian general active in the first half of the 4th century BC. During his career he was involved in several battles, both on land and sea. The orator Demosthenes described him as one of the most ...

was also sent to the Egyptian Pharaoh Tachos, who was also fighting against the Achaemenid king. According to Xenophon

Xenophon of Athens (; ; 355/354 BC) was a Greek military leader, philosopher, and historian. At the age of 30, he was elected as one of the leaders of the retreating Ancient Greek mercenaries, Greek mercenaries, the Ten Thousand, who had been ...

, Agesilaus, in order to gain money for prosecuting the war, supported the satrap

A satrap () was a governor of the provinces of the ancient Median kingdom, Median and Achaemenid Empire, Persian (Achaemenid) Empires and in several of their successors, such as in the Sasanian Empire and the Hellenistic period, Hellenistic empi ...

Ariobarzanes of Phrygia in his revolt against Artaxerxes II

Arses (; 445 – 359/8 BC), known by his regnal name Artaxerxes II ( ; ), was King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire from 405/4 BC to 358 BC. He was the son and successor of Darius II () and his mother was Parysatis.

Soon after his accession, Ar ...

in 364 (Revolt of the Satraps

The Great Satraps' Revolt, or the Revolts of the Satraps (c. 370-c.360 BCE), was a rebellion in the Achaemenid Empire of several satraps in western Anatolia against the authority of the Great King Artaxerxes II (r. 404-359/8). The Satraps who revo ...

).

Again, in 362, Epaminondas almost succeeded in seizing the city of Sparta with a rapid and unexpected march. The Battle of Mantinea, in which Agesilaus took no part, was followed by a general peace: Sparta, however, stood aloof, hoping even yet to recover her supremacy.

Expedition to Egypt

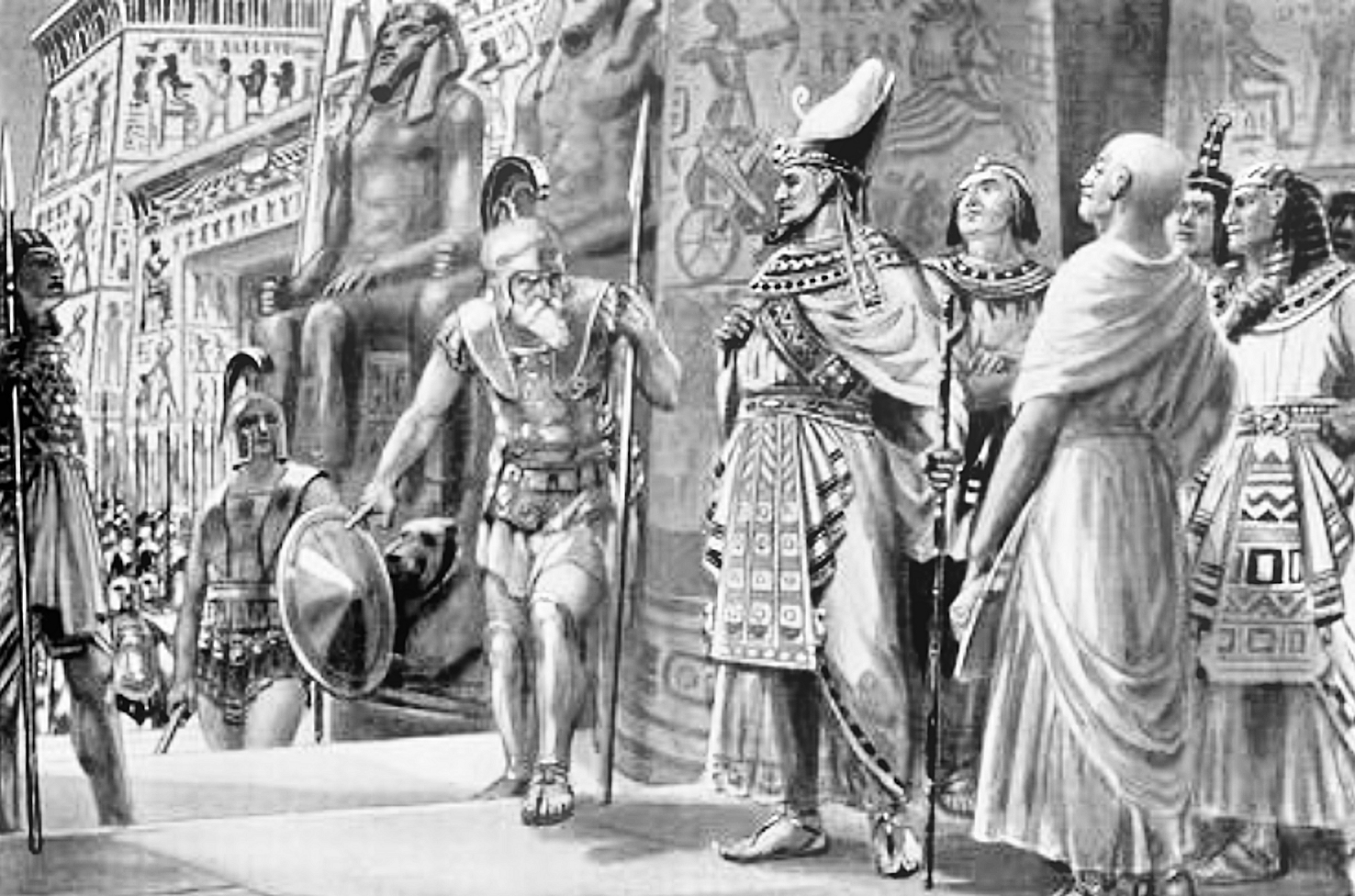

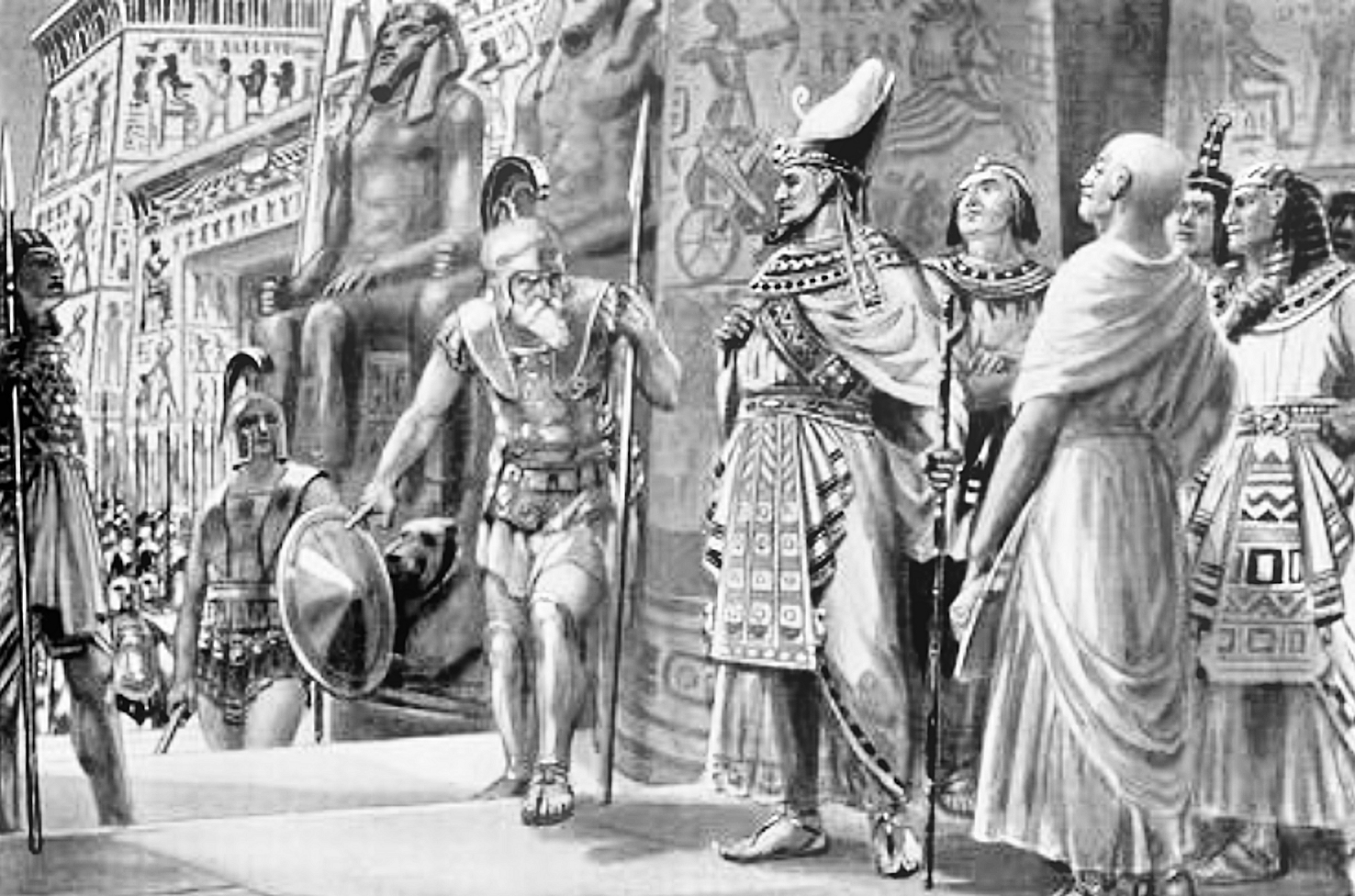

Sometime after the Battle of Mantineia, Agesilaus went to

Sometime after the Battle of Mantineia, Agesilaus went to Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

at the head of a mercenary

A mercenary is a private individual who joins an armed conflict for personal profit, is otherwise an outsider to the conflict, and is not a member of any other official military. Mercenaries fight for money or other forms of payment rather t ...

force to aid the king Nectanebo I and his regent Teos against Persia. In the summer of 358, he transferred his services to Teos's cousin and rival, Nectanebo II

Nectanebo II (Egyptian language, Egyptian: ; ) was the last native ruler of ancient Egypt, as well as the third and last pharaoh of the Thirtieth Dynasty of Egypt, Thirtieth Dynasty, reigning from 358 to c.340 BC.

During the reign of Nectanebo ...

, who, in return for his help, gave him a sum of over 200 talents. On his way home Agesilaus died in Cyrenaica

Cyrenaica ( ) or Kyrenaika (, , after the city of Cyrene), is the eastern region of Libya. Cyrenaica includes all of the eastern part of Libya between the 16th and 25th meridians east, including the Kufra District. The coastal region, als ...

, around the age of 84, after a reign of some 41 years. His body was embalmed in wax, and buried at Sparta.

He was succeeded by his son Archidamus III

Archidamus III (died 338 BC) ( ) was the son of Agesilaus II and Kings of Sparta, king of Sparta from 360 to 338 BC.

Biography

While still a prince, he was the Pederasty in ancient Greece#Terminology, eispnílas (, inspirer, or pederastic ...

.

Legacy

Agesilaus was of small stature and unimpressive appearance, and was lame from birth. These facts were used as an argument against his succession, anoracle

An oracle is a person or thing considered to provide insight, wise counsel or prophetic predictions, most notably including precognition of the future, inspired by deities. If done through occultic means, it is a form of divination.

Descript ...

having warned Sparta against a "lame reign." Most ancient writers considered him a highly successful leader in guerrilla warfare

Guerrilla warfare is a form of unconventional warfare in which small groups of irregular military, such as rebels, partisans, paramilitary personnel or armed civilians, which may include recruited children, use ambushes, sabotage, terrori ...

, alert and quick, yet cautious—a man, moreover, whose personal bravery was rarely questioned in his own time. Of his courage, temperance, and hardiness, many instances are cited, and to these were added the less Spartan qualities of kindliness and tenderness as a father and a friend. As examples, there was the story of his riding a stick-horse with his children and upon being discovered by a friend desiring that the friend not mention what he had seen until he was the father of children; and because of the affection of his son Archidamus for Cleonymus, he saved Sphodrias

Sphodrias () (d. 371 BC) was a Spartan general during the Spartan Hegemony over Greece. As governor of Thespiai in 378 BC, he made an unsuccessful attack against Athens without any order from Sparta. He was put on trial for this act, but unexpecte ...

, Cleonymus' father, from execution for his incursion into Piraeus

Piraeus ( ; ; , Ancient: , Katharevousa: ) is a port city within the Athens urban area ("Greater Athens"), in the Attica region of Greece. It is located southwest of Athens city centre along the east coast of the Saronic Gulf in the Ath ...

and dishonourable retreat in 378. Modern writers tend to be slightly more critical of Agesilaus' reputation and achievements, reckoning him an excellent soldier, but one who had a poor understanding of sea power and siege-craft.

As a statesman he won himself both enthusiastic adherents and bitter enemies. Agesilaus was most successful in the opening and closing periods of his reign: commencing but then surrendering a glorious career in Asia; and in extreme age, maintaining his prostrate country. Other writers acknowledge his extremely high popularity at home, but suggest his occasionally rigid and arguably irrational political loyalties and convictions contributed greatly to Spartan decline, notably his unremitting hatred of Thebes, which led to Sparta's humiliation at the Battle of Leuctra

The Battle of Leuctra (, ) was fought on 6 July 371 BC between the Boeotians led by the Thebes (Greece), Thebans, and the History of Sparta, Spartans along with their allies amidst the post–Corinthian War conflict. The battle took place in the ...

and thus the end of Spartan hegemony. Historian J. B. Bury remarks that "there is something melancholy about his career:" born into a Sparta that was the unquestioned continental power of Hellas, the Sparta which mourned him eighty four years later had suffered a series of military defeats which would have been unthinkable to his forebears, had seen its population severely decline, and had run so short of money that its soldiers were increasingly sent on campaigns fought more for money than for defense or glory.

Plutarch also describes how often, to remove the threat of instigators of internal dissension, Agesilaus would send his enemies abroad with governorships, where they often were corrupt and procured themselves enemies. Agesilaus would then protect them against these new enemies of theirs, so as to make them his friends. As a result, he no longer had to face internal opposition, as his enemies had henceforth become allies.

As for his personal life, though he had two daughters, Eupolia and Prolyta, and a wife, Cleora, he nonetheless had the habit of forming homosexual "attachments for young men".

Other historical accounts paint Agesilaus as a prototype for the ideal leader. His awareness, thoughtfulness, and wisdom were all traits to be emulated diplomatically, while his bravery and shrewdness in battle epitomised the heroic Greek commander. These historians point towards the unstable oligarchies established by Lysander in the former Athenian Empire and the failures of Spartan leaders (such as Pausanias and Kleombrotos) for the eventual suppression of Spartan power. The ancient historian

Other historical accounts paint Agesilaus as a prototype for the ideal leader. His awareness, thoughtfulness, and wisdom were all traits to be emulated diplomatically, while his bravery and shrewdness in battle epitomised the heroic Greek commander. These historians point towards the unstable oligarchies established by Lysander in the former Athenian Empire and the failures of Spartan leaders (such as Pausanias and Kleombrotos) for the eventual suppression of Spartan power. The ancient historian Xenophon

Xenophon of Athens (; ; 355/354 BC) was a Greek military leader, philosopher, and historian. At the age of 30, he was elected as one of the leaders of the retreating Ancient Greek mercenaries, Greek mercenaries, the Ten Thousand, who had been ...

was a huge admirer and served under Agesilaus during the campaigns into Asia Minor

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

.

Plutarch

Plutarch (; , ''Ploútarchos'', ; – 120s) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo (Delphi), Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''Parallel Lives'', ...

includes among Agesilaus' 78 essays and speeches comprising the apophthegmata Agesilaus' letter to the ephor

The ephors were a board of five magistrates in ancient Sparta. They had an extensive range of judicial, religious, legislative, and military powers, and could shape Sparta's home and foreign affairs.

The word "''ephors''" (Ancient Greek ''éph ...

s on his recall:

And when asked whether Agesilaus wanted a memorial erected in his honour:

Agesilaus lived in the most frugal style alike at home and in the field, and though his campaigns were undertaken largely to secure booty, he was content to enrich the state and his friends and to return as poor as he had set forth.Plutarch

Plutarch (; , ''Ploútarchos'', ; – 120s) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo (Delphi), Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''Parallel Lives'', ...

, '' Apophthegmata Laconica''

Notes

References

Sources

Ancient sources

*Plutarch

Plutarch (; , ''Ploútarchos'', ; – 120s) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo (Delphi), Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''Parallel Lives'', ...

, ''Parallel Lives

*

Culture of ancient Greece

Culture of ancient Rome

Ancient Greek biographical works

Ethics literature

History books about ancient Rome

Cultural depictions of Gaius Marius

Cultural depictions of Mark Antony

Cultural depictions of Cicero

...

''.

*Xenophon

Xenophon of Athens (; ; 355/354 BC) was a Greek military leader, philosopher, and historian. At the age of 30, he was elected as one of the leaders of the retreating Ancient Greek mercenaries, Greek mercenaries, the Ten Thousand, who had been ...

'', Hellenica

''Hellenica'' () simply means writings on Greek (Hellenic) subjects. Several histories of the 4th-century BC Greece have borne the conventional Latin title ''Hellenica'', of which very few survive.Murray, Oswyn, "Greek Historians", in John Boardma ...

.''

Modern sources

* Hans Beck & Peter Funke, ''Federalism in Greek Antiquity'', Cambridge University Press, 2015. * Paul Cartledge, ''Sparta and Lakonia, A Regional History 1300–362 BC'', London, Routledge, 1979 (originally published in 1979). * * George L. Cawkwell, "Agesilaus and Sparta", ''The Classical Quarterly'' 26 (1976): 62–84. *David, Ephraim. ''Sparta Between Empire and Revolution (404-243 BC): Internal Problems and Their Impact on Contemporary Greek Consciousness.'' New York: Arno Press, 1981. *Forrest, W.G. ''A History of Sparta, 950-192 B.C.'' 2d ed. London: Duckworth, 1980. *Dustin A. Gish, "Spartan Justice: The Conspiracy of Kinadon in Xenophon's ''Hellenika''", in ''Polis'', vol. 26, no. 2, 2009, pp. 339–369. * *Hamilton, Charles D. ''Sparta's Bitter Victories: Politics and Diplomacy in the Corinthian War.'' Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1979. *D. M. Lewis, John Boardman, Simon Hornblower, M. Ostwald (editors), ''The Cambridge Ancient History

''The Cambridge Ancient History'' is a multi-volume work of ancient history from Prehistory to Late Antiquity, published by Cambridge University Press. The first series, consisting of 12 volumes, was planned in 1919 by Irish historian J. B. Bur ...

, vol. VI, The Fourth Century B.C.'', Cambridge University Press, 1994.

*

*Anton Powell (editor), ''A Companion to Sparta, Volume I'', Hoboken/Chichester, Wiley Blackwell, 2018.

*D. R. Shipley, ''A Commentary on Plutarch's'' Life of Agesilaos'': Response to Sources in the Presentation of Character'', Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1997.

*Debby Sneed,Disability and Infanticide in Ancient Greece

, ''Hesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens'', Vol. 90, No. 4, 2021, pp. 747–772. * Maria Stamatopoulou,

Thessalians Abroad, the Case of Pharsalos

, in ''Mediterranean Historical Review'', vol. 22.2 (2007), pp. 211–236. *Graham Wylie, "Agesilaus and the Battle of Sardis", in ''Klio'', n°74 (1992), pp. 118–130. {{DEFAULTSORT:Agesilaus 02 440s BC births Year of birth uncertain 358 BC deaths Year of death uncertain 4th-century BC Spartans Eurypontid kings of Sparta Ancient Greek generals Spartan hegemony