Abstract Variety on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Algebraic varieties are the central objects of study in

Algebraic varieties are the central objects of study in

A plane projective curve is the zero locus of an irreducible homogeneous polynomial in three indeterminates. The projective line P1 is an example of a projective curve; it can be viewed as the curve in the projective plane defined by . For another example, first consider the affine cubic curve

:

in the 2-dimensional affine space (over a field of characteristic not two). It has the associated cubic homogeneous polynomial equation:

:

which defines a curve in P2 called an elliptic curve. The curve has genus one (

A plane projective curve is the zero locus of an irreducible homogeneous polynomial in three indeterminates. The projective line P1 is an example of a projective curve; it can be viewed as the curve in the projective plane defined by . For another example, first consider the affine cubic curve

:

in the 2-dimensional affine space (over a field of characteristic not two). It has the associated cubic homogeneous polynomial equation:

:

which defines a curve in P2 called an elliptic curve. The curve has genus one (

Algebraic varieties are the central objects of study in

Algebraic varieties are the central objects of study in algebraic geometry

Algebraic geometry is a branch of mathematics, classically studying zeros of multivariate polynomials. Modern algebraic geometry is based on the use of abstract algebraic techniques, mainly from commutative algebra, for solving geometrical ...

, a sub-field of mathematics

Mathematics is an area of knowledge that includes the topics of numbers, formulas and related structures, shapes and the spaces in which they are contained, and quantities and their changes. These topics are represented in modern mathematics ...

. Classically, an algebraic variety is defined as the set of solutions of a system of polynomial equations over the real or complex numbers. Modern definitions generalize this concept in several different ways, while attempting to preserve the geometric intuition behind the original definition.

Conventions regarding the definition of an algebraic variety differ slightly. For example, some definitions require an algebraic variety to be irreducible, which means that it is not the union of two smaller sets that are closed

Closed may refer to:

Mathematics

* Closure (mathematics), a set, along with operations, for which applying those operations on members always results in a member of the set

* Closed set, a set which contains all its limit points

* Closed interval, ...

in the Zariski topology. Under this definition, non-irreducible algebraic varieties are called algebraic sets. Other conventions do not require irreducibility.

The fundamental theorem of algebra establishes a link between algebra and geometry by showing that a monic polynomial (an algebraic object) in one variable with complex number coefficients is determined by the set of its roots (a geometric object) in the complex plane

In mathematics, the complex plane is the plane formed by the complex numbers, with a Cartesian coordinate system such that the -axis, called the real axis, is formed by the real numbers, and the -axis, called the imaginary axis, is formed by the ...

. Generalizing this result, Hilbert's Nullstellensatz provides a fundamental correspondence between ideals

Ideal may refer to:

Philosophy

* Ideal (ethics), values that one actively pursues as goals

* Platonic ideal, a philosophical idea of trueness of form, associated with Plato

Mathematics

* Ideal (ring theory), special subsets of a ring considered ...

of polynomial rings and algebraic sets. Using the ''Nullstellensatz'' and related results, mathematicians have established a strong correspondence between questions on algebraic sets and questions of ring theory. This correspondence is a defining feature of algebraic geometry.

Many algebraic varieties are manifold

In mathematics, a manifold is a topological space that locally resembles Euclidean space near each point. More precisely, an n-dimensional manifold, or ''n-manifold'' for short, is a topological space with the property that each point has a n ...

s, but an algebraic variety may have singular points while a manifold cannot. Algebraic varieties can be characterized by their dimension. Algebraic varieties of dimension one are called algebraic curves and algebraic varieties of dimension two are called algebraic surface

In mathematics, an algebraic surface is an algebraic variety of dimension two. In the case of geometry over the field of complex numbers, an algebraic surface has complex dimension two (as a complex manifold, when it is non-singular) and so of di ...

s.

In the context of modern scheme A scheme is a systematic plan for the implementation of a certain idea.

Scheme or schemer may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''The Scheme'' (TV series), a BBC Scotland documentary series

* The Scheme (band), an English pop band

* ''The Schem ...

theory, an algebraic variety over a field is an integral (irreducible and reduced) scheme over that field whose structure morphism is separated and of finite type.

Overview and definitions

An ''affine variety'' over analgebraically closed field

In mathematics, a field is algebraically closed if every non-constant polynomial in (the univariate polynomial ring with coefficients in ) has a root in .

Examples

As an example, the field of real numbers is not algebraically closed, because ...

is conceptually the easiest type of variety to define, which will be done in this section. Next, one can define projective and quasi-projective varieties in a similar way. The most general definition of a variety is obtained by patching together smaller quasi-projective varieties. It is not obvious that one can construct genuinely new examples of varieties in this way, but Nagata gave an example of such a new variety in the 1950s.

Affine varieties

For an algebraically closed field and a natural number , let be an affine -space over , identified to through the choice of anaffine coordinate system

In mathematics, an affine space is a geometric structure that generalizes some of the properties of Euclidean spaces in such a way that these are independent of the concepts of distance and measure of angles, keeping only the properties relat ...

. The polynomials in the ring can be viewed as ''K''-valued functions on by evaluating at the points in , i.e. by choosing values in ''K'' for each ''xi''. For each set ''S'' of polynomials in , define the zero-locus ''Z''(''S'') to be the set of points in on which the functions in ''S'' simultaneously vanish, that is to say

:

A subset ''V'' of is called an affine algebraic set if ''V'' = ''Z''(''S'') for some ''S''. A nonempty affine algebraic set ''V'' is called irreducible if it cannot be written as the union of two proper algebraic subsets. An irreducible affine algebraic set is also called an affine variety. (Many authors use the phrase ''affine variety'' to refer to any affine algebraic set, irreducible or not.Hartshorne, p.xv, notes that his choice is not conventional; see for example, Harris, p.3)

Affine varieties can be given a natural topology by declaring the closed set

In geometry, topology, and related branches of mathematics, a closed set is a set whose complement is an open set. In a topological space, a closed set can be defined as a set which contains all its limit points. In a complete metric space, a cl ...

s to be precisely the affine algebraic sets. This topology is called the Zariski topology.

Given a subset ''V'' of , we define ''I''(''V'') to be the ideal of all polynomial functions vanishing on ''V'':

:

For any affine algebraic set ''V'', the coordinate ring or structure ring of ''V'' is the quotient of the polynomial ring by this ideal.

Projective varieties and quasi-projective varieties

Let be an algebraically closed field and let be the projective ''n''-space over . Let in be a homogeneous polynomial of degree ''d''. It is not well-defined to evaluate on points in in homogeneous coordinates. However, because is homogeneous, meaning that , it ''does'' make sense to ask whether vanishes at a point . For each set ''S'' of homogeneous polynomials, define the zero-locus of ''S'' to be the set of points in on which the functions in ''S'' vanish: : A subset ''V'' of is called a projective algebraic set if ''V'' = ''Z''(''S'') for some ''S''. An irreducible projective algebraic set is called a projective variety. Projective varieties are also equipped with the Zariski topology by declaring all algebraic sets to be closed. Given a subset ''V'' of , let ''I''(''V'') be the ideal generated by all homogeneous polynomials vanishing on ''V''. For any projective algebraic set ''V'', the coordinate ring of ''V'' is the quotient of the polynomial ring by this ideal. A quasi-projective variety is aZariski open

In algebraic geometry and commutative algebra, the Zariski topology is a topology which is primarily defined by its closed sets. It is very different from topologies which are commonly used in the real or complex analysis; in particular, it is ...

subset of a projective variety. Notice that every affine variety is quasi-projective. Notice also that the complement of an algebraic set in an affine variety is a quasi-projective variety; in the context of affine varieties, such a quasi-projective variety is usually not called a variety but a constructible set.

Abstract varieties

In classical algebraic geometry, all varieties were by definitionquasi-projective varieties In mathematics, a quasi-projective variety in algebraic geometry is a locally closed subset of a projective variety, i.e., the intersection inside some projective space of a Zariski-open and a Zariski-closed subset. A similar definition is used in ...

, meaning that they were open subvarieties of closed subvarieties of projective space

In mathematics, the concept of a projective space originated from the visual effect of perspective, where parallel lines seem to meet ''at infinity''. A projective space may thus be viewed as the extension of a Euclidean space, or, more generally ...

. For example, in Chapter 1 of Hartshorne a ''variety'' over an algebraically closed field is defined to be a quasi-projective variety, but from Chapter 2 onwards, the term variety (also called an abstract variety) refers to a more general object, which locally is a quasi-projective variety, but when viewed as a whole is not necessarily quasi-projective; i.e. it might not have an embedding into projective space

In mathematics, the concept of a projective space originated from the visual effect of perspective, where parallel lines seem to meet ''at infinity''. A projective space may thus be viewed as the extension of a Euclidean space, or, more generally ...

. So classically the definition of an algebraic variety required an embedding into projective space, and this embedding was used to define the topology on the variety and the regular functions on the variety. The disadvantage of such a definition is that not all varieties come with natural embeddings into projective space. For example, under this definition, the product is not a variety until it is embedded into the projective space; this is usually done by the Segre embedding. However, any variety that admits one embedding into projective space admits many others by composing the embedding with the Veronese embedding. Consequently, many notions that should be intrinsic, such as the concept of a regular function, are not obviously so.

The earliest successful attempt to define an algebraic variety abstractly, without an embedding, was made by André Weil

André Weil (; ; 6 May 1906 – 6 August 1998) was a French mathematician, known for his foundational work in number theory and algebraic geometry. He was a founding member and the ''de facto'' early leader of the mathematical Bourbaki group. Th ...

. In his ''Foundations of Algebraic Geometry

''Foundations of Algebraic Geometry'' is a book by that develops algebraic geometry over field (mathematics), fields of any characteristic (algebra), characteristic. In particular it gives a careful treatment of intersection theory by defining th ...

'', Weil defined an abstract algebraic variety using valuations. Claude Chevalley made a definition of a scheme A scheme is a systematic plan for the implementation of a certain idea.

Scheme or schemer may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''The Scheme'' (TV series), a BBC Scotland documentary series

* The Scheme (band), an English pop band

* ''The Schem ...

, which served a similar purpose, but was more general. However, Alexander Grothendieck's definition of a scheme is more general still and has received the most widespread acceptance. In Grothendieck's language, an abstract algebraic variety is usually defined to be an integral, separated scheme of finite type over an algebraically closed field, although some authors drop the irreducibility or the reducedness or the separateness condition or allow the underlying field to be not algebraically closed.Liu, Qing. ''Algebraic Geometry and Arithmetic Curves'', p. 55 Definition 2.3.47, and p. 88 Example 3.2.3 Classical algebraic varieties are the quasiprojective integral separated finite type schemes over an algebraically closed field.

Existence of non-quasiprojective abstract algebraic varieties

One of the earliest examples of a non-quasiprojective algebraic variety were given by Nagata. Nagata's example was notcomplete

Complete may refer to:

Logic

* Completeness (logic)

* Completeness of a theory, the property of a theory that every formula in the theory's language or its negation is provable

Mathematics

* The completeness of the real numbers, which implies t ...

(the analog of compactness), but soon afterwards he found an algebraic surface that was complete and non-projective. Since then other examples have been found; for example, it is straightforward to construct a toric variety that is not quasi-projective but complete.

Examples

Subvariety

A subvariety is a subset of a variety that is itself a variety (with respect to the structure induced from the ambient variety). For example, every open subset of a variety is a variety. See also closed immersion. Hilbert's Nullstellensatz says that closed subvarieties of an affine or projective variety are in one-to-one correspondence with the prime ideals or homogeneous prime ideals of the coordinate ring of the variety.Affine variety

Example 1

Let , and A2 be the two-dimensional affine space over C. Polynomials in the ring C 'x'', ''y''can be viewed as complex valued functions on A2 by evaluating at the points in A2. Let subset ''S'' of C 'x'', ''y''contain a single element : : The zero-locus of is the set of points in A2 on which this function vanishes: it is the set of all pairs of complex numbers (''x'', ''y'') such that ''y'' = 1 − ''x''. This is called aline

Line most often refers to:

* Line (geometry), object with zero thickness and curvature that stretches to infinity

* Telephone line, a single-user circuit on a telephone communication system

Line, lines, The Line, or LINE may also refer to:

Arts ...

in the affine plane. (In the classical topology coming from the topology on the complex numbers, a complex line is a real manifold of dimension two.) This is the set :

:

Thus the subset of A2 is an algebraic set. The set ''V'' is not empty. It is irreducible, as it cannot be written as the union of two proper algebraic subsets. Thus it is an affine algebraic variety.

Example 2

Let , and A2 be the two-dimensional affine space over C. Polynomials in the ring C 'x'', ''y''can be viewed as complex valued functions on A2 by evaluating at the points in A2. Let subset ''S'' of C 'x'', ''y''contain a single element ''g''(''x'', ''y''): : The zero-locus of ''g''(''x'', ''y'') is the set of points in A2 on which this function vanishes, that is the set of points (''x'',''y'') such that ''x''2 + ''y''2 = 1. As ''g''(''x'', ''y'') is an absolutely irreducible polynomial, this is an algebraic variety. The set of its real points (that is the points for which ''x'' and ''y'' are real numbers), is known as the unit circle; this name is also often given to the whole variety.Example 3

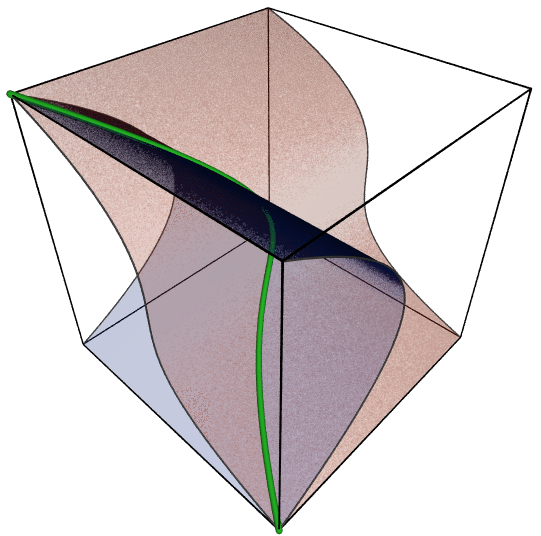

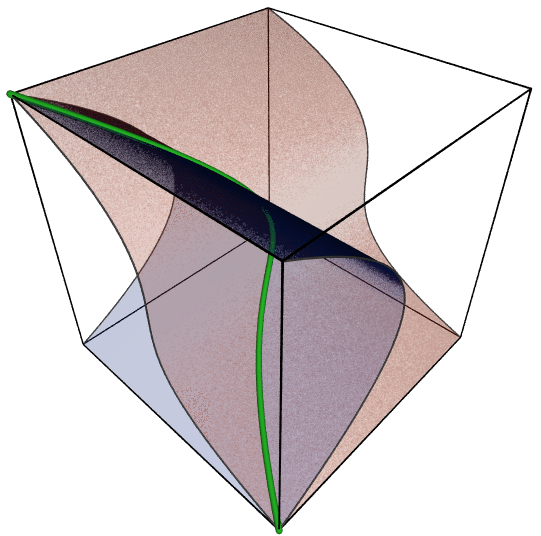

The following example is neither a hypersurface, nor a linear space, nor a single point. Let A3 be the three-dimensional affine space over C. The set of points (''x'', ''x''2, ''x''3) for ''x'' in C is an algebraic variety, and more precisely an algebraic curve that is not contained in any plane.Harris, p.9; that it is irreducible is stated as an exercise in Hartshorne p.7 It is the twisted cubic shown in the above figure. It may be defined by the equations : The irreducibility of this algebraic set needs a proof. One approach in this case is to check that the projection (''x'', ''y'', ''z'') → (''x'', ''y'') isinjective

In mathematics, an injective function (also known as injection, or one-to-one function) is a function that maps distinct elements of its domain to distinct elements; that is, implies . (Equivalently, implies in the equivalent contrapositiv ...

on the set of the solutions and that its image is an irreducible plane curve.

For more difficult examples, a similar proof may always be given, but may imply a difficult computation: first a Gröbner basis computation to compute the dimension, followed by a random linear change of variables (not always needed); then a Gröbner basis computation for another monomial order

In mathematics, a monomial order (sometimes called a term order or an admissible order) is a total order on the set of all ( monic) monomials in a given polynomial ring, satisfying the property of respecting multiplication, i.e.,

* If u \leq v and ...

ing to compute the projection and to prove that it is generically injective and that its image is a hypersurface, and finally a polynomial factorization to prove the irreducibility of the image.

General linear group

The set of ''n''-by-''n'' matrices over the base field ''k'' can be identified with the affine ''n''2-space with coordinates such that is the (''i'', ''j'')-th entry of the matrix . The determinant is then a polynomial in and thus defines the hypersurface in . The complement of is then an open subset of that consists of all the invertible ''n''-by-''n'' matrices, the general linear group . It is an affine variety, since, in general, the complement of a hypersurface in an affine variety is affine. Explicitly, consider where the affine line is given coordinate ''t''. Then amounts to the zero-locus in of the polynomial in : : i.e., the set of matrices ''A'' such that has a solution. This is best seen algebraically: the coordinate ring of is the localization , which can be identified with . The multiplicative group k* of the base field ''k'' is the same as and thus is an affine variety. A finite product of it is an algebraic torus, which is again an affine variety. A general linear group is an example of a linear algebraic group, an affine variety that has a structure of a group in such a way the group operations are morphism of varieties.Projective variety

Aprojective variety

In algebraic geometry, a projective variety over an algebraically closed field ''k'' is a subset of some projective ''n''-space \mathbb^n over ''k'' that is the zero-locus of some finite family of homogeneous polynomials of ''n'' + 1 variables w ...

is a closed subvariety of a projective space. That is, it is the zero locus of a set of homogeneous polynomials that generate a prime ideal

In algebra, a prime ideal is a subset of a ring that shares many important properties of a prime number in the ring of integers. The prime ideals for the integers are the sets that contain all the multiples of a given prime number, together with ...

.

Example 1

A plane projective curve is the zero locus of an irreducible homogeneous polynomial in three indeterminates. The projective line P1 is an example of a projective curve; it can be viewed as the curve in the projective plane defined by . For another example, first consider the affine cubic curve

:

in the 2-dimensional affine space (over a field of characteristic not two). It has the associated cubic homogeneous polynomial equation:

:

which defines a curve in P2 called an elliptic curve. The curve has genus one (

A plane projective curve is the zero locus of an irreducible homogeneous polynomial in three indeterminates. The projective line P1 is an example of a projective curve; it can be viewed as the curve in the projective plane defined by . For another example, first consider the affine cubic curve

:

in the 2-dimensional affine space (over a field of characteristic not two). It has the associated cubic homogeneous polynomial equation:

:

which defines a curve in P2 called an elliptic curve. The curve has genus one (genus formula

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial nomenclat ...

); in particular, it is not isomorphic to the projective line P1, which has genus zero. Using genus to distinguish curves is very basic: in fact, the genus is the first invariant one uses to classify curves (see also the construction of moduli of algebraic curves).

Example 2: Grassmannian

Let ''V'' be a finite-dimensional vector space. TheGrassmannian variety

In mathematics, the Grassmannian is a space that parameterizes all -Dimension, dimensional linear subspaces of the -dimensional vector space . For example, the Grassmannian is the space of lines through the origin in , so it is the same as the ...

''Gn''(''V'') is the set of all ''n''-dimensional subspaces of ''V''. It is a projective variety: it is embedded into a projective space via the Plücker embedding In mathematics, the Plücker map embeds the Grassmannian \mathbf(k,V), whose elements are ''k''-dimensional subspaces of an ''n''-dimensional vector space ''V'', in a projective space, thereby realizing it as an algebraic variety.

More precisely ...

:

:

where ''bi'' are any set of linearly independent vectors in ''V'', is the ''n''-th exterior power of ''V'', and the bracket 'w''means the line spanned by the nonzero vector ''w''.

The Grassmannian variety comes with a natural vector bundle (or locally free sheaf in other terminology) called the tautological bundle, which is important in the study of characteristic classes such as Chern classes.

Jacobian variety

Let ''C'' be a smooth complete curve and the Picard group of it; i.e., the group of isomorphism classes of line bundles on ''C''. Since ''C'' is smooth, can be identified as the divisor class group of ''C'' and thus there is the degree homomorphism . The Jacobian variety of ''C'' is the kernel of this degree map; i.e., the group of the divisor classes on ''C'' of degree zero. A Jacobian variety is an example of anabelian variety

In mathematics, particularly in algebraic geometry, complex analysis and algebraic number theory, an abelian variety is a projective algebraic variety that is also an algebraic group, i.e., has a group law that can be defined by regular func ...

, a complete variety with a compatible abelian group structure on it (the name "abelian" is however not because it is an abelian group). An abelian variety turns out to be projective ( theta functions in the algebraic setting gives an embedding); thus, is a projective variety. The tangent space to at the identity element is naturally isomorphic to hence, the dimension of is the genus of .

Fix a point on . For each integer , there is a natural morphism

: