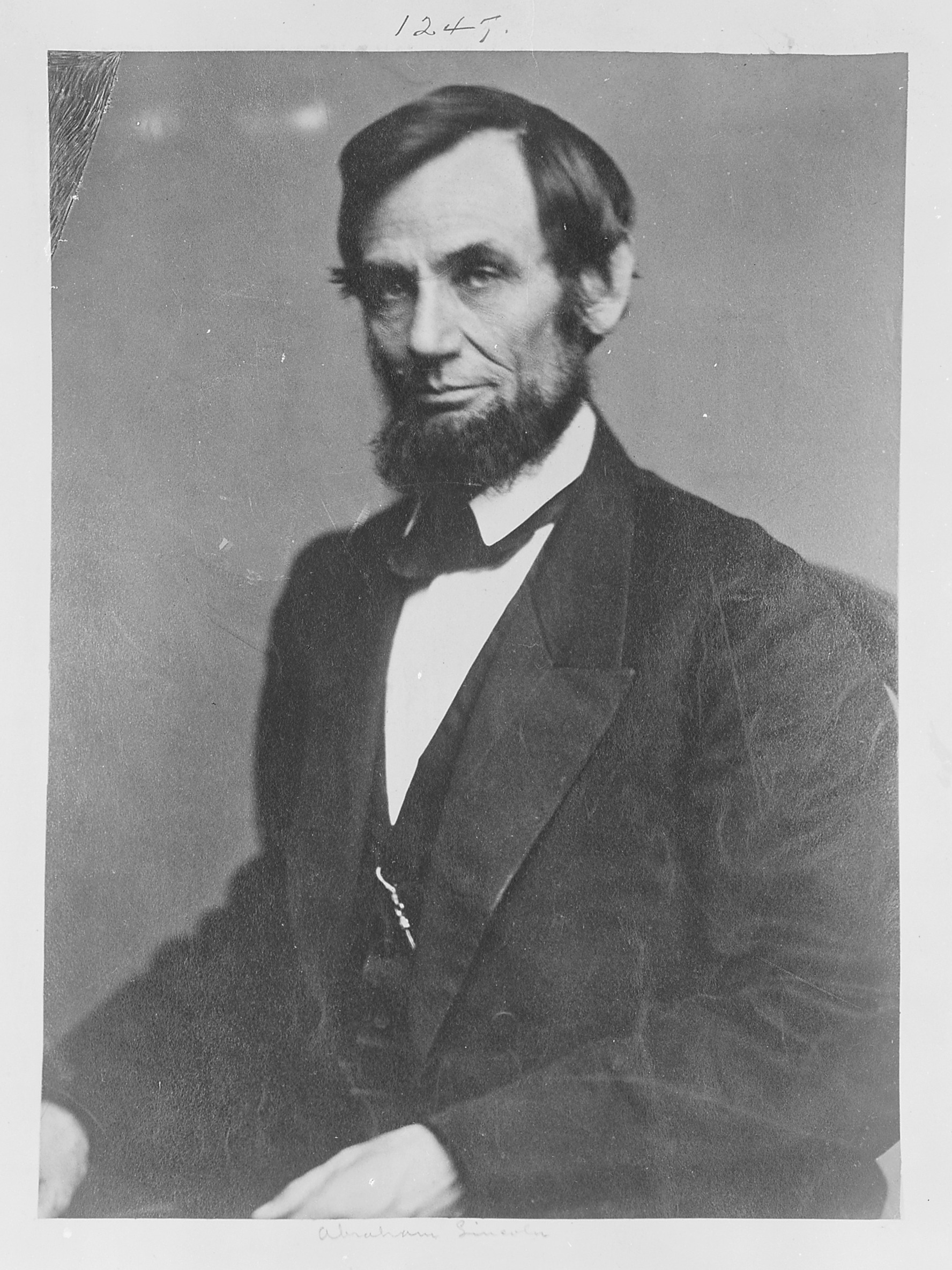

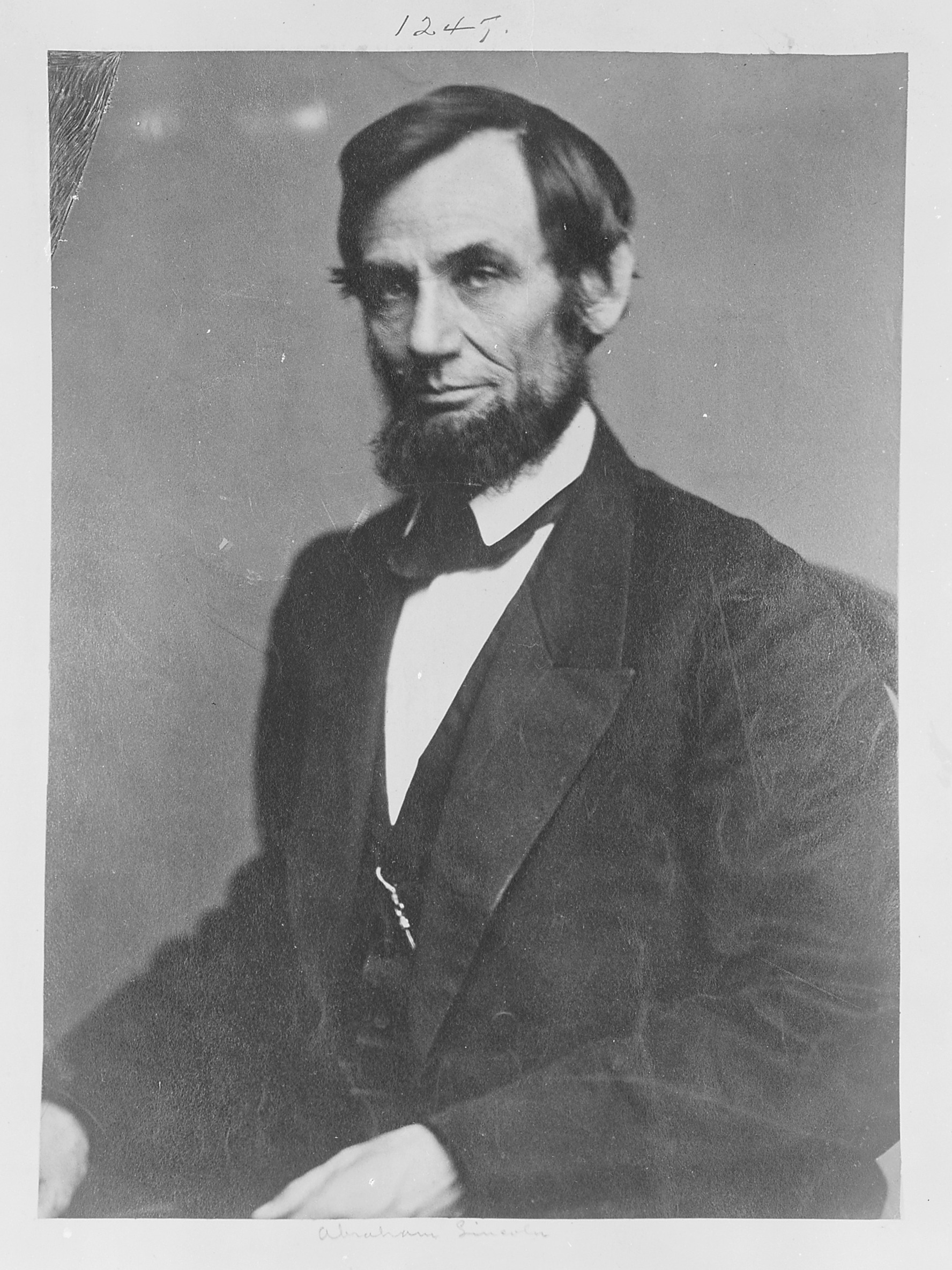

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th

president of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal government of t ...

, serving from 1861 until

his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

, defeating the

Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America (CSA), also known as the Confederate States (C.S.), the Confederacy, or Dixieland, was an List of historical unrecognized states and dependencies, unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United State ...

and playing a major role in the

abolition of slavery

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was France in 1315, but it was later used in its colonies. T ...

.

Lincoln was born into

poverty

Poverty is a state or condition in which an individual lacks the financial resources and essentials for a basic standard of living. Poverty can have diverse Biophysical environmen ...

in

Kentucky

Kentucky (, ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north, West Virginia to the ...

and raised on the

frontier

A frontier is a political and geographical term referring to areas near or beyond a boundary.

Australia

The term "frontier" was frequently used in colonial Australia in the meaning of country that borders the unknown or uncivilised, th ...

. He was self-educated and became a lawyer,

Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. It borders on Lake Michigan to its northeast, the Mississippi River to its west, and the Wabash River, Wabash and Ohio River, Ohio rivers to its ...

state

legislator

A legislator, or lawmaker, is a person who writes and passes laws, especially someone who is a member of a legislature. Legislators are often elected by the people, but they can be appointed, or hereditary. Legislatures may be supra-nat ...

, and

U.S. representative

The United States House of Representatives is a chamber of the bicameral United States Congress; it is the lower house, with the U.S. Senate being the upper house. Together, the House and Senate have the authority under Article One of th ...

. Angered by the

Kansas–Nebraska Act

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 () was a territorial organic act that created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska. It was drafted by Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas, passed by the 33rd United States Congress, and signed into law b ...

of 1854, which opened the territories to slavery, he became a leader of the new

Republican Party. He reached a national audience in the

1858 Senate campaign debates against

Stephen A. Douglas

Stephen Arnold Douglas (né Douglass; April 23, 1813 – June 3, 1861) was an American politician and lawyer from Illinois. As a United States Senate, U.S. senator, he was one of two nominees of the badly split Democratic Party (United States) ...

. Lincoln won the

1860 presidential election

United States presidential election, Presidential elections were held in the United States on November 6, 1860. The History of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party ticket of Abraham Lincoln and Hannibal Hamlin emerged victoriou ...

, which the

South

South is one of the cardinal directions or compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both west and east.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Proto-Germanic ''*sunþa ...

viewed as a further threat to states' rights and slavery, and Southern states began

seceding to form the Confederate States of America. A month after Lincoln assumed the presidency, Confederate forces

attacked Fort Sumter, starting the Civil War.

Lincoln, a

moderate Republican, had to navigate a contentious array of factions in managing conflicting political opinion during the war effort. Lincoln closely supervised the strategy and tactics in the war effort, including the selection of generals, and implemented a

naval blockade

A navy, naval force, military maritime fleet, war navy, or maritime force is the branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral, or ocean-borne combat operations ...

of Southern ports. He suspended the writ of ''

habeas corpus

''Habeas corpus'' (; from Medieval Latin, ) is a legal procedure invoking the jurisdiction of a court to review the unlawful detention or imprisonment of an individual, and request the individual's custodian (usually a prison official) to ...

'' in April 1861, an action that Chief Justice

Roger Taney

Roger Brooke Taney ( ; March 17, 1777 – October 12, 1864) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the fifth chief justice of the United States, holding that office from 1836 until his death in 1864. Taney delivered the majority opin ...

found unconstitutional in ''

Ex parte Merryman

''Ex parte Merryman'', 17 F. Cas. 144 (C.C.D. Md. 1861) (No. 9487), was a controversial U.S. federal court case during the American Civil War. It was a test of the authority of the President to suspend "the privilege of the wri ...

'', and he averted war with Britain by defusing the

''Trent'' Affair. On January 1, 1863, he issued the

Emancipation Proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation, officially Proclamation 95, was a presidential proclamation and executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the American Civil War. The Proclamation had the eff ...

, which declared the slaves in the states "in rebellion" to be free. On November 19, 1863, he delivered the

Gettysburg Address

The Gettysburg Address is a Public speaking, speech delivered by Abraham Lincoln, the 16th President of the United States, U.S. president, following the Battle of Gettysburg during the American Civil War. The speech has come to be viewed as one ...

, which became one of the most famous speeches in American history. He promoted the

Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution

The Thirteenth Amendment (Amendment XIII) to the United States Constitution abolished slavery and involuntary servitude, except as punishment for a crime. The amendment was passed by the Senate on April 8, 1864, by the House of Representative ...

, which, in 1865, abolished slavery, except as punishment for a crime.

Re-elected in 1864, he sought to heal the war-torn nation through

Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Union ...

.

On April 14, 1865, five days after the

Confederate surrender at Appomattox, he was attending a play at

Ford's Theatre

Ford's Theatre is a theater located in Washington, D.C., which opened in 1863. The theater is best known for being the site of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. On the night of April 14, 1865, John Wilkes Booth entered the theater box where ...

in Washington, D.C., when he was fatally shot by Confederate sympathizer

John Wilkes Booth

John Wilkes Booth (May 10, 1838April 26, 1865) was an American stage actor who Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, assassinated United States president Abraham Lincoln at Ford's Theatre in Washington, D.C., on April 14, 1865. A member of the p ...

. Lincoln is remembered as a

martyr

A martyr (, ''mártys'', 'witness' Word stem, stem , ''martyr-'') is someone who suffers persecution and death for advocating, renouncing, or refusing to renounce or advocate, a religious belief or other cause as demanded by an external party. In ...

and a national hero for his wartime leadership and for his efforts to preserve the Union and abolish slavery.

He is often ranked in both popular and scholarly polls as the greatest president in American history.

Family and childhood

Early life

Abraham Lincoln was born on February 12, 1809, in a log cabin on

Sinking Spring Farm near

Hodgenville, Kentucky

Hodgenville is a home rule-class city in LaRue County, Kentucky, United States. It is the seat of its county. Hodgenville sits along the North Fork of the Nolin River. The population was 3,206 at the 2010 census. It is included in the Elizabet ...

.

[ The second child of ]Thomas Lincoln

Thomas Lincoln Sr. (January 6, 1778 – January 17, 1851) was an American farmer, carpenter, and father of the 16th president of the United States, Abraham Lincoln. Unlike some of his ancestors, Thomas could not write. He struggled to make a su ...

and Nancy Hanks Lincoln, he was a descendant of Samuel Lincoln, an Englishman who migrated from England to Massachusetts

Massachusetts ( ; ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Maine to its east, Connecticut and Rhode ...

in 1638, and of the Harrison family of Virginia

The Harrison family of Virginia has a history in American political family, politics, public service, and religious ministry, beginning in the Colony of Virginia during the 1600s. Family members include a Founding Fathers of the United States, F ...

. His paternal grandfather and namesake, Captain Abraham Lincoln, moved the family from Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

to Kentucky

Kentucky (, ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north, West Virginia to the ...

. The captain was killed in a Native American raid in 1786. Thomas, Abraham's father, then worked at odd jobs in Kentucky and Tennessee

Tennessee (, ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Kentucky to the north, Virginia to the northeast, North Carolina t ...

before the family settled in Hardin County, Kentucky

Hardin County is a county located in the central part of the U.S. state of Kentucky. Its county seat is Elizabethtown. The county was formed in 1792. Hardin County is part of the Elizabethtown-Fort Knox, KY Metropolitan Statistical Area, as ...

, in the early 1800s. Lincoln's mother Nancy is widely assumed to have been the daughter of Lucy Hanks. Thomas and Nancy married on June 12, 1806, and moved to Elizabethtown, Kentucky

Elizabethtown is a home rule-class city in Hardin County, Kentucky, United States, and its county seat. The population was 31,394 at the 2020 census, making it the ninth-most populous city in the state. It is the principal city of the Elizab ...

. They had three children: Sarah, Abraham, and Thomas; Thomas died as an infant.

Thomas Lincoln bought multiple farms in Kentucky but could not get clear property titles to any, losing hundreds of acres in legal disputes. In 1816, the family moved to Indiana

Indiana ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Michigan to the northwest, Michigan to the north and northeast, Ohio to the east, the Ohio River and Kentucky to the s ...

, where land titles were more reliable. They settled on a forested plot in Little Pigeon Creek Community, Indiana. In Kentucky and Indiana, Thomas worked as a farmer, cabinetmaker, and carpenter. At various times he owned farms, livestock, and town lots, appraised estates, and served on county patrols. Thomas and Nancy were members of a Separate Baptist Church, a pious evangelical group whose members largely condemned slavery. Overcoming financial challenges, Thomas obtained clear title

Clear title is the phrase used to state that the owner of real property owns it free and clear of encumbrances. In a more limited sense, it is used to state that, although the owner does not own clear title, it is nevertheless within the power of ...

to in Little Pigeon Creek Community in 1827.

On October 5, 1818, Nancy Lincoln died from milk sickness

Milk sickness, also known as tremetol vomiting, is a kind of poisoning characterized by trembling, vomiting, and severe intestinal pain that affects individuals who ingest milk, other dairy products, or meat from a cow that has fed on white sna ...

, leaving 11-year-old Sarah in charge of a household including her father, 9-year-old Abraham, and Nancy's 19-year-old orphan cousin, Dennis Hanks. Ten years later, on January 20, 1828, Sarah died in childbirth, devastating Lincoln. On December 2, 1819, Thomas married Sarah Bush Johnston, a widow with three children of her own.[ Abraham became close to his stepmother and called her "Mama".

]

Education and move to Illinois

Lincoln was largely self-educated. His formal schooling was from itinerant teacher

Itinerant teachers (also called "visiting" or "peripatetic" teachers) are traveling schoolteachers. They are sometimes specialized to work in the trades, healthcare, or the field of special education, sometimes providing individual tutoring.

H ...

s. It included two short stints in Kentucky, where he learned to read, but probably not to write. After moving to Indiana at age seven, he attended school only sporadically, for a total of less than 12 months by age 15. Nonetheless, he was an avid reader and retained a lifelong interest in learning.

When Lincoln was a teenager his father relied heavily on him for farmwork and for supplementary income, hiring the boy out to area farmers and pocketing the money, as was allowed by law at the time. Lincoln and some friends took goods by flatboat

A flatboat (or broadhorn) was a rectangular flat-bottomed boat with square ends used to transport freight and passengers on inland waterways in the United States. The flatboat could be any size, but essentially it was a large, sturdy tub with a ...

to New Orleans

New Orleans (commonly known as NOLA or The Big Easy among other nicknames) is a Consolidated city-county, consolidated city-parish located along the Mississippi River in the U.S. state of Louisiana. With a population of 383,997 at the 2020 ...

, Louisiana, where he first witnessed slave market

A slave market is a place where slaves are bought and sold. These markets are a key phenomenon in the history of slavery.

Asia

Central Asia

Since antiquity, cities along the Silk road of Central Asia, had been centers of slave trade. In ...

s.[

In March 1830, fearing another milk-sickness outbreak, several members of the extended Lincoln family, including Abraham, moved west to Illinois and settled in Macon County. Abraham became increasingly distant from Thomas, in part due to his father's lack of interest in education; he would later refuse to attend his father's deathbed or funeral in 1851.][

]

Marriage and children

Some historians, such as Michael Burlingame, identify Lincoln's first romantic interest as Ann Rutledge

Ann Mayes Rutledge (January 7, 1813 – August 25, 1835) was allegedly Abraham Lincoln's first love.

Early life

Born near Henderson, Kentucky, Ann Mayes Rutledge was the third of 10 children born to Mary Ann Miller Rutledge and James Rutledg ...

, a young woman also from Kentucky whom he met when he moved to New Salem, Illinois. Lewis Gannett

Lewis Alan Gannett (born 1952) is an American writer. He is the author of two novels, ''The Living One'' (1993) and ''Magazine Beach'' (1996). He edited the late C.A. Tripp's ''The Intimate World of Abraham Lincoln'' (2005), a controversial study ...

, however, disputes that the evidence supports a romantic relationship between the two. David Herbert Donald

David Herbert Donald (October 1, 1920 – May 17, 2009) was an American historian, best known for his 1995 biography of Abraham Lincoln. He twice won the Pulitzer Prize for Biography, for books about Thomas Wolfe and Charles Sumner; he published ...

states that "How that friendship etween Lincoln and Rutledgedeveloped into a romance cannot be reconstructed from the record". Rutledge died on August 25, 1835, of typhoid fever

Typhoid fever, also known simply as typhoid, is a disease caused by '' Salmonella enterica'' serotype Typhi bacteria, also called ''Salmonella'' Typhi. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often th ...

. Lincoln took her death very hard, sinking into a serious depression and contemplating suicide.Springfield, Illinois

Springfield is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the U.S. state of Illinois. Its population was 114,394 at the 2020 United States census, which makes it the state's List of cities in Illinois, seventh-most populous cit ...

, and the following year they became engaged. She was the daughter of Robert Smith Todd, a wealthy lawyer and businessman in Lexington, Kentucky

Lexington is a Consolidated city-county, consolidated city coterminous with and the county seat of Fayette County, Kentucky, United States. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census the city's population was 322,570, making it the List of ...

. Lincoln initially broke off the engagement in early 1841, but the two were reconciled and married on November 4, 1842. In 1844, the couple bought a house

A House were an Irish rock band that where active in Dublin from 1985 to 1997, and recognized for the clever, "often bitter or irony laden lyrics of frontman Dave Couse ... bolstered by the and'sseemingly effortless musicality". The single " En ...

in Springfield near his law office.

The marriage was turbulent; Mary was verbally abusive and at times physically violent towards her husband. They had four sons. The eldest, Robert Todd Lincoln

Robert Todd Lincoln (August 1, 1843 – July 26, 1926) was an American lawyer and businessman. The eldest son of President Abraham Lincoln and Mary Todd Lincoln, he was the only one of their four children to survive past the teenage years ...

, was born in 1843, and was the only child to live to maturity. Edward Baker Lincoln (Eddie), born in 1846, died February 1, 1850, probably of tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB), also known colloquially as the "white death", or historically as consumption, is a contagious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can al ...

. Lincoln's third son, "Willie" Lincoln, was born on December 21, 1850, and died of a fever at the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. Located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue Northwest (Washington, D.C.), NW in Washington, D.C., it has served as the residence of every U.S. president ...

on February 20, 1862. The youngest, Thomas "Tad" Lincoln, was born on April 4, 1853, and died of edema at age 18 on July 16, 1871. Lincoln loved children, and the Lincolns were not considered to be strict with their own. The deaths of Eddie and Willie had profound effects on both parents. Lincoln suffered from " melancholy", a condition now thought to be clinical depression

Major depressive disorder (MDD), also known as clinical depression, is a mental disorder characterized by at least two weeks of pervasive low mood, low self-esteem, and loss of interest or pleasure in normally enjoyable activities. Intro ...

.

Early vocations and militia service

In 1831, Thomas moved the family to a new homestead in Coles County, Illinois

Coles County is a county in Illinois. As of the 2020 census, the population was 46,863. Its county seat is Charleston, which is also the home of Eastern Illinois University.

Coles County is part of the Charleston– Mattoon, IL Micropolitan ...

, after which Abraham struck out on his own. He made his home in New Salem, Illinois, for six years. During 1831 and 1832, Lincoln worked at a general store in New Salem. He gained a reputation for strength and courage after winning a wrestling

Wrestling is a martial art, combat sport, and form of entertainment that involves grappling with an opponent and striving to obtain a position of advantage through different throws or techniques, within a given ruleset. Wrestling involves di ...

match with the leader of a group of ruffians known as the Clary's Grove boys. In 1832, he declared his candidacy for the Illinois House of Representatives

The Illinois House of Representatives is the lower house of the Illinois General Assembly. The body was created by the first Illinois Constitution adopted in 1818. The House under the constitution as amended in 1980 consists of 118 representativ ...

, though he interrupted his campaign to serve as a captain in the Illinois Militia

In the United States, state defense forces (SDFs) are military units that operate under the sole authority of a state government. State defense forces are authorized by state and federal law and are under the command of the governor of each st ...

during the Black Hawk War

The Black Hawk War was a conflict between the United States and Native Americans in the United States, Native Americans led by Black Hawk (Sauk leader), Black Hawk, a Sauk people, Sauk leader. The war erupted after Black Hawk and a group of ...

. He was elected the captain of his militia company but did not see combat. In his political campaigning, Lincoln advocated for navigational improvements on the Sangamon River

The Sangamon River is a principal tributary of the Illinois River, approximately long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed May 13, 2011 in central Illinois in the United Sta ...

. He drew crowds as a raconteur

A humorist is an intellectual who uses humor, or wit, in writing or public speaking. A raconteur is one who tells anecdotes in a skillful and amusing way.

Henri Bergson writes that a humorist's work grows from viewing the morals of society.

...

, but he lacked name recognition, powerful friends, and money, and he lost the election.

When Lincoln returned home from the war, he planned to become a blacksmith

A blacksmith is a metalsmith who creates objects primarily from wrought iron or steel, but sometimes from #Other metals, other metals, by forging the metal, using tools to hammer, bend, and cut (cf. tinsmith). Blacksmiths produce objects such ...

but instead purchased a New Salem general store in partnership with William Berry. Because a license was required to sell customers alcoholic beverages, Berry obtained bartending licenses for Lincoln and himself, and in 1833 the Lincoln–Berry General Store became a tavern

A tavern is a type of business where people gather to drink alcoholic beverages and be served food such as different types of roast meats and cheese, and (mostly historically) where travelers would receive lodging. An inn is a tavern that ...

as well. But according to Burlingame, Berry was "an undisciplined, hard-drinking fellow", and Lincoln "was too soft-hearted to deny anyone credit"; although the economy was booming, the business struggled and went into debt, prompting Lincoln to sell his share.

Lincoln served as New Salem's postmaster

A postmaster is the head of an individual post office, responsible for all postal activities in a specific post office. When a postmaster is responsible for an entire mail distribution organization (usually sponsored by a national government), ...

and later as county surveyor, but he continued his voracious reading and decided to become a lawyer. Rather than studying in the office of an established attorney, as was customary, Lincoln read law

Reading law was the primary method used in common law countries, particularly the United States, for people to prepare for and enter the legal profession before the advent of law schools. It consisted of an extended internship or apprenticeship un ...

on his own, borrowing legal texts, including Blackstone's '' Commentaries'' and Chitty

The Chitty, also known as the Chetty or Chetti Melaka, are an ethnic group whose members are of primarily Tamil descent, found mainly and initially in Melaka, Malaysia, where they settled around the 16th century, and in Singapore where they mi ...

's ''Pleadings'', from attorney John Todd Stuart

John Todd Stuart (November 10, 1807 – November 28, 1885) was a lawyer and a U.S. Representative from Illinois.

Born near Lexington, Kentucky, Stuart graduated from Centre College, Danville, Kentucky, in 1826. He then studied law, was a ...

. He later said of his legal education that he "studied with nobody."

Early political offices and prairie lawyer

Illinois state legislature (1834–1842)

In Lincoln's second state house campaign in 1834, this time as a Whig and supporter of Whig leader

In Lincoln's second state house campaign in 1834, this time as a Whig and supporter of Whig leader Henry Clay

Henry Clay (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the United States Senate, U.S. Senate and United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives. He was the seventh Spea ...

, he finished second among thirteen candidates running for four places. Lincoln echoed Clay's support for the American Colonization Society

The American Colonization Society (ACS), initially the Society for the Colonization of Free People of Color of America, was an American organization founded in 1816 by Robert Finley to encourage and support the repatriation of freeborn peop ...

, which advocated abolition in conjunction with settling freed slaves in Liberia

Liberia, officially the Republic of Liberia, is a country on the West African coast. It is bordered by Sierra Leone to Liberia–Sierra Leone border, its northwest, Guinea to Guinea–Liberia border, its north, Ivory Coast to Ivory Coast–Lib ...

. The Whigs also favored economic modernization in banking, tariffs to fund internal improvements

Internal improvements is the term used historically in the United States for public works from the end of the American Revolution through much of the 19th century, mainly for the creation of a transportation infrastructure: roads, turnpikes, can ...

such as railroads, and urbanization.

Lincoln served four terms in the Illinois House of Representatives for Sangamon County

Sangamon County is a county located near the center of the U.S. state of Illinois. According to the 2020 census, it had a population of 196,343. Its county seat and largest city is Springfield, the state capital.

Sangamon County is includ ...

. In this role, he championed construction of the Illinois and Michigan Canal

The Illinois and Michigan Canal connected the Great Lakes to the Mississippi River and the Gulf of Mexico. In Illinois, it ran from the Chicago River in Bridgeport, Chicago to the Illinois River at LaSalle-Peru. The canal crossed the Chicago ...

. Lincoln also voted to expand suffrage beyond White landowners to all White men. Lincoln was admitted to the Illinois bar on September 9, 1836. He moved to Springfield and began to practice law under John T. Stuart, Mary Todd's cousin. He partnered for several years with Stephen T. Logan and, in 1844, began his practice with William Herndon.

On January 27, 1838, Lincoln delivered an address at the Lyceum in Springfield, after the murder of the anti-slavery newspaper editor Elijah Parish Lovejoy

Elijah Parish Lovejoy (November 9, 1802 – November 7, 1837) was an American Presbyterianism, Presbyterian minister (Christianity), minister, journalist, Editing, newspaper editor, and Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist. After his ...

. In this ostensibly non-partisan speech Lincoln indirectly attacked Stephen Douglas

Stephen Arnold Douglas ( né Douglass; April 23, 1813 – June 3, 1861) was an American politician and lawyer from Illinois. As a U.S. senator, he was one of two nominees of the badly split Democratic Party to run for president in the 1860 ...

and the Democratic Party, who the Whigs argued were supporting "mobocracy"; he also attacked anti-abolitionism and racial bigotry. He was criticized in the press for a planned duel with James Shields, whom he had ridiculed in letters published under the name "Aunt Rebecca"; though the duel ultimately did not take place, Burlingame noted that "the affair embarrassed Lincoln terribly".

U.S. House of Representatives (1847–1849)

In 1843, Lincoln sought the Whig nomination for Illinois's 7th district seat in the U.S. House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is a chamber of the bicameral United States Congress; it is the lower house, with the U.S. Senate being the upper house. Together, the House and Senate have the authority under Article One of th ...

; John J. Hardin was the winning candidate, though Lincoln convinced the party convention to limit Hardin to one term. Lincoln not only gained the nomination in 1846, but also won the election. The only Whig in the Illinois delegation, he was assigned to the Committee on Post Office and Post Roads and the Committee on Expenditures in the War Department. Lincoln teamed with Joshua R. Giddings

Joshua Reed Giddings (October 6, 1795 – May 27, 1864) was an American attorney, politician and abolitionist. He represented Northeast Ohio in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1838 to 1859. He was at first a member of the Whig Party an ...

on a bill to abolish slavery in the District of Columbia

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and Federal district of the United States, federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from ...

, but dropped the bill when it failed to attract support from most other Whigs.

Lincoln spoke against the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War (Spanish language, Spanish: ''guerra de Estados Unidos-México, guerra mexicano-estadounidense''), also known in the United States as the Mexican War, and in Mexico as the United States intervention in Mexico, ...

(1846–1848), for which he said President James K. Polk

James Knox Polk (; November 2, 1795 – June 15, 1849) was the 11th president of the United States, serving from 1845 to 1849. A protégé of Andrew Jackson and a member of the Democratic Party, he was an advocate of Jacksonian democracy and ...

"had some strong motive ... to involve the two countries in a war, and trusting to escape scrutiny, by fixing the public gaze upon the exceeding brightness of military glory—that attractive rainbow, that rises in showers of blood". He supported the Wilmot Proviso

The Wilmot Proviso was an unsuccessful 1846 proposal in the United States Congress to ban slavery in territory acquired from Mexico in the Mexican–American War. The conflict over the Wilmot Proviso was one of the major events leading to the ...

, a failed 1846 proposal to ban slavery in any U.S. territory won from Mexico. Polk insisted that Mexican soldiers had begun the war by "invading the territory of the State of Texas ... and shedding the blood of our citizens on our own soil". In his 1847 " spot resolutions", Lincoln rhetorically demanded that Polk tell Congress the exact "spot" where this occurred, but the Polk administration did not respond.[ His approach and rhetoric cost Lincoln political support in his district, and newspapers derisively nicknamed him "spotty Lincoln".][

Lincoln had pledged in 1846 to serve only one term in the House. Realizing Henry Clay was unlikely to win the presidency, he supported ]Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor (November 24, 1784 – July 9, 1850) was an American military officer and politician who was the 12th president of the United States, serving from 1849 until his death in 1850. Taylor was a career officer in the United States ...

for the Whig nomination in the 1848 presidential election. Taylor won and Lincoln hoped in vain to be appointed commissioner of the United States General Land Office

The General Land Office (GLO) was an Independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the United States government responsible for Public domain (land), public domain lands in the United States. It was created in 1812 ...

. The administration offered to appoint him secretary of the Oregon Territory

The Territory of Oregon was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from August 14, 1848, until February 14, 1859, when the southwestern portion of the territory was admitted to the United States, Union as the Oreg ...

instead. This would have disrupted his legal and political career in Illinois, so he declined and resumed his law practice.

Prairie lawyer

In his Springfield practice, according to Donald, Lincoln handled "virtually every kind of business that could come before a prairie lawyer". He dealt with many transportation cases in the midst of the nation's western expansion, particularly river barge conflicts under the new railroad bridges. In 1849 he received a patent for a flotation device for the movement of riverboat

A riverboat is a watercraft designed for inland navigation on lakes, rivers, and artificial waterways. They are generally equipped and outfitted as work boats in one of the carrying trades, for freight or people transport, including luxury ...

s in shallow water and Lincoln initially favored riverboat legal interests, but he represented whoever hired him. He represented a bridge company against a riverboat company in '' Hurd v. Rock Island Bridge Company'', a landmark case involving a canal boat that sank after hitting a bridge. His patent was never commercialized, but it made Lincoln the only president to hold a patent. Lincoln appeared before the Illinois Supreme Court in 411 cases. From 1853 to 1860, one of his largest clients was the Illinois Central Railroad

The Illinois Central Railroad , sometimes called the Main Line of Mid-America, is a railroad in the Central United States. Its primary routes connected Chicago, Illinois, with New Orleans, New Orleans, Louisiana, and Mobile, Alabama, and thus, ...

, who Lincoln successfully sued to recover his legal fees.

Lincoln represented William "Duff" Armstrong in his 1858 trial for the murder of James Preston Metzker. The case is famous for Lincoln's use of a fact established by judicial notice

Judicial notice is a rule in the law of evidence that allows a fact to be introduced into evidence if the truth of that fact is so notorious or well-known, or so authoritatively attested, that it cannot reasonably be doubted. This is done upon the ...

to challenge the credibility of an eyewitness. After a witness testified to seeing the crime in the moonlight, Lincoln produced a '' Farmers' Almanac'' showing the Moon was at a low angle, drastically reducing visibility. Armstrong was acquitted. In an 1859 murder case, he defended "Peachy" Quinn Harrison, the grandson of Peter Cartwright, Lincoln's political opponent. Harrison was charged with the murder of Greek Crafton who, according to Cartwright, said as he lay dying that he had "brought it upon myself" and that he forgave Harrison. Lincoln angrily protested the judge's initial decision to exclude Cartwright's claim as hearsay

Hearsay, in a legal forum, is an out-of-court statement which is being offered in court for the truth of what was asserted. In most courts, hearsay evidence is Inadmissible evidence, inadmissible (the "hearsay evidence rule") unless an exception ...

. Lincoln argued that the testimony involved a dying declaration and so was not subject to the hearsay rule. Instead of holding Lincoln in contempt of court

Contempt of court, often referred to simply as "contempt", is the crime of being disobedient to or disrespectful toward a court of law and its officers in the form of behavior that opposes or defies the authority, justice, and dignity of the co ...

as expected, the judge, a Democrat, admitted the testimony into evidence, resulting in Harrison's acquittal.

Republican politics (1854–1860)

Emergence as Republican leader

The Compromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five separate bills passed by the United States Congress in September 1850 that temporarily defused tensions between slave and free states during the years leading up to the American Civil War. Designe ...

failed to alleviate tensions over slavery between the slave-holding South and the free North. As the slavery debate in the Nebraska

Nebraska ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders South Dakota to the north; Iowa to the east and Missouri to the southeast, both across the Missouri River; Ka ...

and Kansas

Kansas ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to the west. Kansas is named a ...

territories became particularly acrimonious, Illinois Senator Stephen A. Douglas proposed popular sovereignty

Popular sovereignty is the principle that the leaders of a state and its government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a State (polity), state.

In the case of its broad associativ ...

as a compromise; the measure would allow the electorate of each territory to decide the status of slavery. The legislation alarmed many Northerners, who sought to prevent the spread of slavery, but Douglas's Kansas–Nebraska Act

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 () was a territorial organic act that created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska. It was drafted by Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas, passed by the 33rd United States Congress, and signed into law b ...

narrowly passed Congress in May 1854. Lincoln's Peoria Speech of October 1854, in which he declared his opposition to slavery, was one of over 170 speeches he delivered in the next six years on the topic of excluding slavery from the territories.[ Lincoln's attacks on the Kansas–Nebraska Act marked his return to political life.

Nationally, the Whigs were irreparably split by the Kansas–Nebraska Act and other ineffective efforts to compromise on the slavery issue. Reflecting on the demise of his party, Lincoln wrote in 1855, "I think I am a whig; but others say there are no whigs, and that I am an abolitionist.... I now do no more than oppose the ''extension'' of slavery." The new Republican Party was formed as a northern party dedicated to anti-slavery, drawing from the anti-slavery wing of the Whig Party and combining ]Free Soil

The Free Soil Party, also called the Free Democratic Party or the Free Democracy, was a political party in the United States from 1848 to 1854, when it merged into the Republican Party. The party was focused on opposing the expansion of slav ...

, Liberty

Liberty is the state of being free within society from oppressive restrictions imposed by authority on one's way of life, behavior, or political views. The concept of liberty can vary depending on perspective and context. In the Constitutional ...

, and anti-slavery Democratic Party members, Lincoln resisted early Republican entreaties, fearing that the new party would become a platform for extreme abolitionists. Lincoln held out hope for rejuvenating the Whigs, though he lamented his party's growing closeness with the nativist Know Nothing

The American Party, known as the Native American Party before 1855 and colloquially referred to as the Know Nothings, or the Know Nothing Party, was an Old Stock Americans, Old Stock Nativism in United States politics, nativist political movem ...

movement. In 1854, Lincoln was elected to the Illinois legislature, but before the term began he declined to take his seat so that he would be eligible to run in the upcoming U.S. Senate election. At that time, senators were elected by state legislatures. After leading in the first six rounds of voting, Lincoln was unable to obtain a majority. Lincoln instructed his backers to vote for Lyman Trumbull

Lyman Trumbull (October 12, 1813 – June 25, 1896) was an American lawyer, judge, and politician who represented the state of Illinois in the United States Senate from 1855 to 1873. Trumbull was a leading abolitionist attorney and key polit ...

, an anti-slavery Democrat who had received few votes in the earlier ballots. Lincoln's decision to withdraw enabled his Whig supporters and Trumbull's anti-slavery Democrats to combine and defeat the mainstream Democratic candidate, Joel Aldrich Matteson

Joel Aldrich Matteson (August 8, 1808 – January 31, 1873) was the tenth Governor of Illinois, serving from 1853 to 1857.

Career

In 1855, he became the first governor to reside in the Illinois Executive Mansion. In January 1855, during the ...

.

1856 campaign

Violent political confrontations in Kansas continued, and opposition to the Kansas–Nebraska Act remained strong throughout the North. As the 1856 elections approached, Lincoln joined the Republicans and attended the Bloomington Convention, where the Illinois Republican Party

The Illinois Republican Party is the affiliate of the Republican Party in the U.S. state of Illinois founded on May 29, 1856. It is run by the Illinois Republican State Central Committee, which consists of 17 members, one representing each of th ...

was established. The convention platform endorsed Congress's right to regulate slavery in the territories and backed the admission of Kansas as a free state. Lincoln gave the final speech of the convention, calling for the preservation of the Union. At the June 1856 Republican National Convention

The 1856 Republican National Convention was a presidential nominating convention that met from June 17 to June 19, 1856, at Musical Fund Hall at 808 Locust Street in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It was the first national nominating conventio ...

, Lincoln received support to run as vice president, but ultimately the party put forward a ticket of John C. Frémont

Major general (United States), Major-General John Charles Frémont (January 21, 1813July 13, 1890) was a United States Army officer, explorer, and politician. He was a United States senator from California and was the first History of the Repub ...

and William Dayton, which Lincoln supported throughout Illinois. The Democrats nominated James Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was the 15th president of the United States, serving from 1857 to 1861. He also served as the United States Secretary of State, secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and represented Pennsylvan ...

and the Know Nothings nominated Millard Fillmore

Millard Fillmore (January 7, 1800 – March 8, 1874) was the 13th president of the United States, serving from 1850 to 1853. He was the last president to be a member of the Whig Party while in the White House, and the last to be neither a De ...

. Buchanan prevailed, while Republican William Henry Bissell won election as Governor of Illinois, and Lincoln became a leading Republican in Illinois.

''Dred Scott v. Sandford''

Dred Scott

Dred Scott ( – September 17, 1858) was an enslaved African American man who, along with his wife, Harriet, unsuccessfully sued for the freedom of themselves and their two daughters, Eliza and Lizzie, in the '' Dred Scott v. Sandford'' case ...

was a slave whose master took him from a slave state to a territory that was free as a result of the Missouri Compromise

The Missouri Compromise (also known as the Compromise of 1820) was federal legislation of the United States that balanced the desires of northern states to prevent the expansion of slavery in the country with those of southern states to expand ...

. After Scott was returned to the slave state, he petitioned a federal court for his freedom. His petition was denied in ''Dred Scott v. Sandford

''Dred Scott v. Sandford'', 60 U.S. (19 How.) 393 (1857), was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court that held the U.S. Constitution did not extend American citizenship to people of black African descent, and therefore they ...

'' (1857). Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger B. Taney

Roger Brooke Taney ( ; March 17, 1777 – October 12, 1864) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the fifth Chief Justice of the United States, chief justice of the United States, holding that office from 1836 until his death in 186 ...

wrote in his opinion that Black people were not citizens and derived no rights from the Constitution, and that the Missouri Compromise was unconstitutional for infringing upon slave owners' property rights. While many Democrats hoped that ''Dred Scott'' would end the dispute over slavery in the territories, the decision sparked further outrage in the North. Lincoln denounced it as the product of a conspiracy of Democrats to support the Slave Power

The Slave Power, or Slavocracy, referred to the perceived political power held by American slaveholders in the federal government of the United States during the Antebellum period. Antislavery campaigners charged that this small group of wealth ...

. He argued that the decision was at variance with the Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of the territory of another state or failed state, or are breaka ...

, which stated that "all men are created equal ... with certain unalienable rights", among them "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness".

Lincoln–Douglas debates and Cooper Union speech

In 1858, Douglas was up for re-election in the U.S. Senate, and Lincoln hoped to defeat him. Many in the party felt that a former Whig should be nominated in 1858, and Lincoln's 1856 campaigning and support of Trumbull had earned him a favor. For the first time, Illinois Republicans held a convention to agree upon a Senate candidate, and Lincoln won the nomination with little opposition. Lincoln accepted the nomination with great enthusiasm and zeal. After his nomination he delivered his House Divided Speech: "A house divided against itself cannot stand." I believe this government cannot endure, permanently half ''slave'' and half ''free''. I do not expect the Union to be ''dissolved''—I do not expect the house to ''fall''—but I ''do'' expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing, or all the other.

The speech created a stark image of the danger of disunion. When informed of Lincoln's nomination, Douglas stated, " incolnis the strong man of the party ... and if I beat him, my victory will be hardly won."

The Senate campaign featured seven debates between Lincoln and Douglas; they had an atmosphere akin to a prizefight and drew thousands. Lincoln warned that the Slave Power was threatening the values of republicanism, and he accused Douglas of distorting Jefferson's premise that all men are created equal

The quotation "all men are created equal" is found in the United States Declaration of Independence and is a phrase that has come to be seen as emblematic of America's founding ideals. The final form of the sentence was stylized by Benjamin Fran ...

. In his Freeport Doctrine

The Freeport Doctrine was articulated by Stephen A. Douglas on August 27, 1858, in Freeport, Illinois, at the second of the Lincoln-Douglas debates. Former one-term U.S. Representative Abraham Lincoln was campaigning to take Douglas's U.S. Senate ...

, Douglas argued that, despite the ''Dred Scott'' decision, which he claimed to support, local settlers, under popular sovereignty

Popular sovereignty is the principle that the leaders of a state and its government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a State (polity), state.

In the case of its broad associativ ...

, should be free to choose whether to allow slavery in their territory. He accused Lincoln of having joined the abolitionists.

Though the Republican legislative candidates won more popular votes, the Democrats won more seats, and the legislature re-elected Douglas. However, Lincoln's articulation of the issues had given him a national political presence. In the aftermath of the 1858 election, newspapers frequently mentioned Lincoln as a potential Republican presidential candidate. While Lincoln was popular in the Midwest

The Midwestern United States (also referred to as the Midwest, the Heartland or the American Midwest) is one of the four census regions defined by the United States Census Bureau. It occupies the northern central part of the United States. It ...

, he lacked support in the Northeast and was unsure whether to seek the office. In January 1860, Lincoln told a group of political allies that he would accept the presidential nomination if offered and, in the following months, William O. Stoddard's ''Central Illinois Gazette'', the ''Chicago Press & Tribune'', and other local papers endorsed his candidacy.

On February 27, 1860, powerful New York Republicans invited Lincoln to give a speech at the Cooper Union. In this address Lincoln argued that the Founding Fathers

The Founding Fathers of the United States, often simply referred to as the Founding Fathers or the Founders, were a group of late-18th-century American revolutionary leaders who united the Thirteen Colonies, oversaw the War of Independence ...

had little use for popular sovereignty and had repeatedly sought to restrict slavery; he insisted that morality required opposition to slavery and rejected any "groping for some middle ground between the right and the wrong". Many in the audience thought he appeared awkward and even ugly. But Lincoln demonstrated intellectual leadership, which brought him into contention for the presidency. Journalist Noah Brooks reported, "No man ever before made such an impression on his first appeal to a New York audience". Historian David Herbert Donald described the speech as "a superb political move for an unannounced presidential aspirant." In response to an inquiry about his ambitions, Lincoln said, "The taste ''is'' in my mouth a little".

1860 presidential election

On May 9–10, 1860, the Illinois Republican State Convention was held in Decatur. Exploiting his embellished frontier legend of clearing land and splitting fence rails, Lincoln's supporters adopted the label of "The Rail Candidate". On May 18 at the

On May 9–10, 1860, the Illinois Republican State Convention was held in Decatur. Exploiting his embellished frontier legend of clearing land and splitting fence rails, Lincoln's supporters adopted the label of "The Rail Candidate". On May 18 at the Republican National Convention

The Republican National Convention (RNC) is a series of presidential nominating conventions held every four years since 1856 by the Republican Party in the United States. They are administered by the Republican National Committee. The goal o ...

in Chicago, Lincoln won the nomination on the third ballot.[ A former Democrat, ]Hannibal Hamlin

Hannibal Hamlin (August 27, 1809 – July 4, 1891) was an American politician and diplomat who was the 15th vice president of the United States, serving from 1861 to 1865, during President Abraham Lincoln's first term. He was the first Republi ...

of Maine, was nominated for vice president to balance the ticket.

Throughout the 1850s, Lincoln had doubted the prospects of civil war, and his supporters rejected claims that his election would incite secession. When Douglas was selected as the candidate of the Northern Democrats, delegates from the Southern slave states elected incumbent Vice President John C. Breckinridge

John Cabell Breckinridge (January 16, 1821 – May 17, 1875) was an American politician who served as the 14th vice president of the United States, with President James Buchanan, from 1857 to 1861. Assuming office at the age of 36, Breckinrid ...

as their candidate. A group of former Whigs and Know Nothings formed the Constitutional Union Party and nominated John Bell of Tennessee. Lincoln and Douglas competed for votes in the North, while Bell and Breckinridge primarily found support in the South. A nationwide militaristic Republican youth organization, the Wide Awakes

The Wide Awakes were a youth organization and later a paramilitary organization cultivated by the Republican Party during the 1860 presidential election in the United States. Using popular social events, an ethos of competitive fraternity, ...

, "turned it into one of the most excited elections in American history" and "triggered massive popular enthusiasm", according to the political historian Jon Grinspan. People of the Northern states knew the Southern states would vote against Lincoln and rallied supporters for him.

As Douglas and the other candidates campaigned, Lincoln gave no speeches, relying on the enthusiasm of the Republican Party. Republican speakers emphasized Lincoln's childhood poverty to demonstrate the power of "free labor", which allowed a common farm boy to work his way to the top by his own efforts. Though he did not give public appearances, many sought to visit and write to Lincoln. In the runup to the election, he took an office in the Illinois state capitol to deal with the influx of attention. He also hired John George Nicolay

John George Nicolay (February 26, 1832 – September 26, 1901) was a German-born American author and diplomat who served as private secretary to U.S. President Abraham Lincoln and later, with John Hay, co-authored '' Abraham Lincoln: A History'', ...

as his personal secretary, who would remain in that role during the presidency.

On November 6, 1860, Lincoln was elected as the first Republican president. His victory was entirely due to his support in the North and West. No ballots were cast for him in 10 of the 15 Southern slave states. Lincoln received 1,866,452 votes, or 39.8 percent of the total in a four-way race, carrying the free Northern states, as well as California and Oregon, and winning the electoral vote decisively.

Presidency (1861–1865)

First term

Secession and inauguration

The South was outraged by Lincoln's election, and secessionists implemented plans to leave the Union before he took office in March 1861.[ On December 20, 1860, South Carolina adopted an ordinance of secession; by February 1, 1861, Florida, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas had followed. Six of these states declared themselves to be a sovereign nation, the ]Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America (CSA), also known as the Confederate States (C.S.), the Confederacy, or Dixieland, was an List of historical unrecognized states and dependencies, unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United State ...

, selecting Jefferson Davis

Jefferson F. Davis (June 3, 1808December 6, 1889) was an American politician who served as the only President of the Confederate States of America, president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. He represented Mississippi in the Unite ...

as its provisional president. The upper South and border states (Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, Kentucky, Missouri, and Arkansas) initially rejected the secessionist appeal. President Buchanan and President-elect Lincoln refused to recognize the Confederacy, declaring secession illegal. On February 11, 1861, Lincoln gave a particularly emotional farewell address upon leaving Springfield for Washington.

Lincoln and the Republicans rejected the proposed Crittenden Compromise

The Crittenden Compromise was an unsuccessful proposal to permanently enshrine slavery in the United States Constitution, and thereby make it unconstitutional for future congresses to end slavery. It was introduced by United States Senator Jo ...

as contrary to the party's platform of free-soil in the territories

A territory is an area of land, sea, or space, belonging or connected to a particular country, person, or animal.

In international politics, a territory is usually a geographic area which has not been granted the powers of self-government, ...

. Lincoln said, "I will suffer death before I consent ... to any concession or compromise which looks like buying the privilege to take possession of this government to which we have a constitutional right". Lincoln supported the Corwin Amendment to the U.S. Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, on March 4, 1789. Originally including seven articles, the Constituti ...

, which would have protected slavery in states where it already existed. The amendment passed Congress and was awaiting ratification by the required three-fourths of the states when Southern states began to secede. On March 4, 1861, in his first inaugural address, Lincoln said that, because he held "such a provision to now be implied constitutional law, I have no objection to its being made express, and irrevocable".

Due to secessionist plots, Lincoln and his train received careful attention to security. The president-elect evaded suspected assassins in Baltimore. He traveled in disguise, wearing a soft felt hat instead of his customary stovepipe hat and draping an overcoat over his shoulders while hunching to conceal his height. On February 23, 1861, he arrived in Washington, D.C., which was placed under military guard. Many in the opposition press criticized his secretive journey; opposition newspapers mocked Lincoln with caricatures showing him sneaking into the capital. Lincoln directed his inaugural address to the South, proclaiming once again that he had no inclination to abolish slavery in the Southern states:

The president ended his address with an appeal to the people of the South: "We are not enemies, but friends.... The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield, and patriot grave, to every living heart and hearthstone ... will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched ... by the better angels of our nature". According to Donald, the failure of the

Due to secessionist plots, Lincoln and his train received careful attention to security. The president-elect evaded suspected assassins in Baltimore. He traveled in disguise, wearing a soft felt hat instead of his customary stovepipe hat and draping an overcoat over his shoulders while hunching to conceal his height. On February 23, 1861, he arrived in Washington, D.C., which was placed under military guard. Many in the opposition press criticized his secretive journey; opposition newspapers mocked Lincoln with caricatures showing him sneaking into the capital. Lincoln directed his inaugural address to the South, proclaiming once again that he had no inclination to abolish slavery in the Southern states:

The president ended his address with an appeal to the people of the South: "We are not enemies, but friends.... The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield, and patriot grave, to every living heart and hearthstone ... will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched ... by the better angels of our nature". According to Donald, the failure of the Peace Conference of 1861

The Peace Conference of 1861 was a meeting of 131 leading American politicians in February 1861, at the Willard Hotel in Washington, D.C., on the eve of the American Civil War. The conference's purpose was to avoid, if possible, the secession of ...

to attract the attendance of seven of the Confederate states signaled that legislative compromise was not a practical expectation.

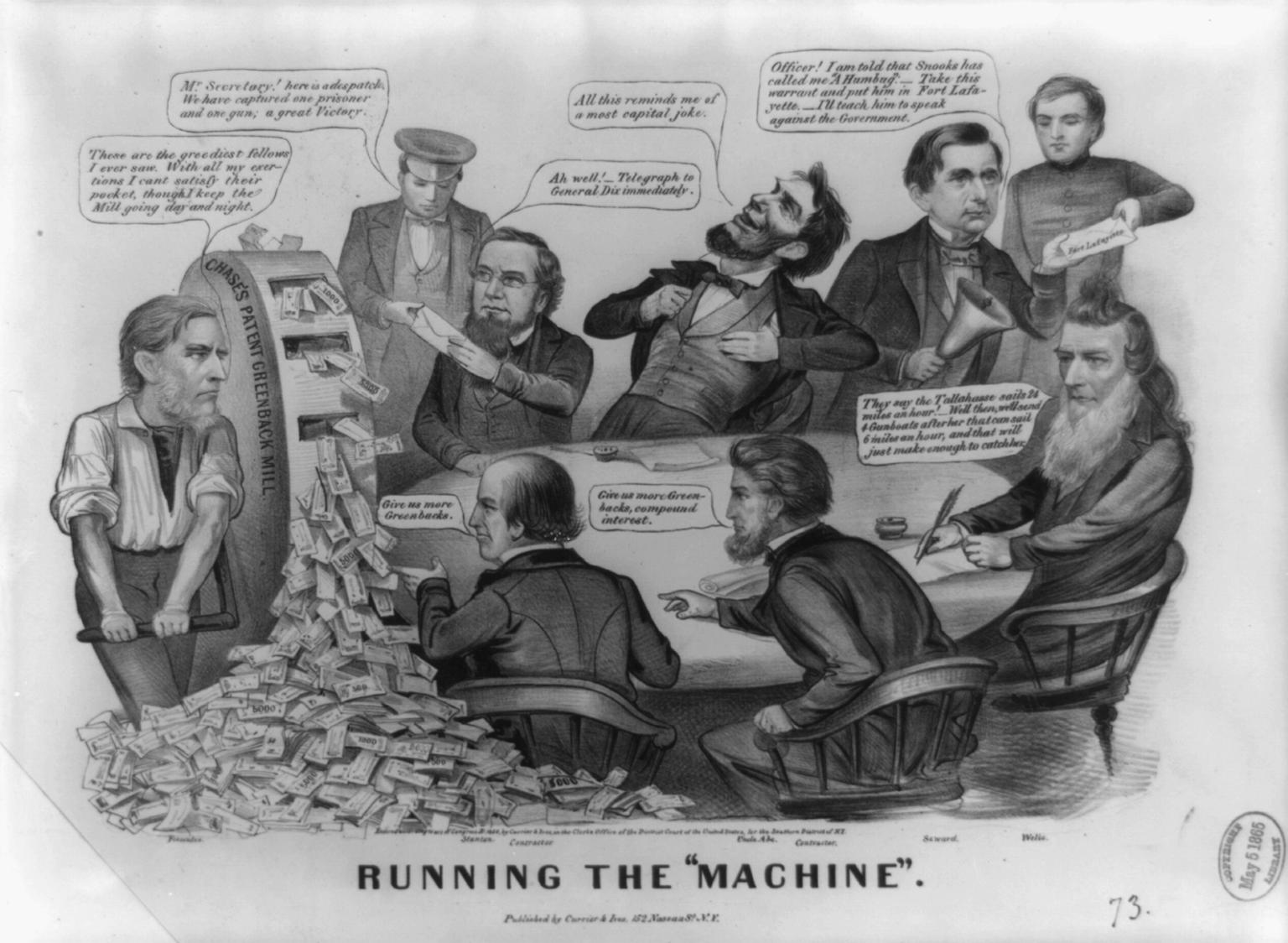

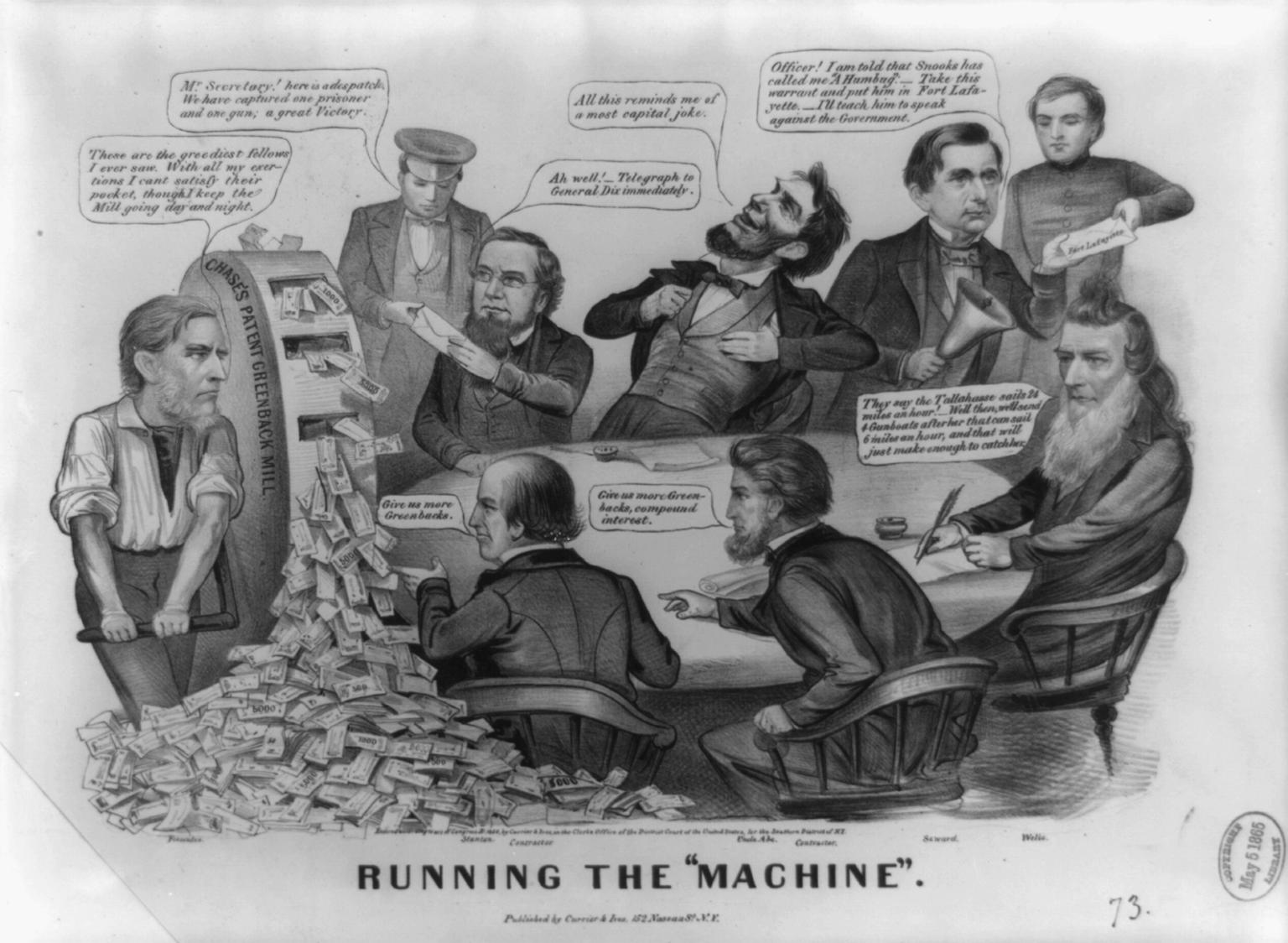

Personnel

In selecting his cabinet, Lincoln chose the men he found the most competent, even when they had been his opponents for the presidency. Lincoln commented on his thought process, "We need the strongest men of the party in the Cabinet. We needed to hold our own people together. I had looked the party over and concluded that these were the very strongest men. Then I had no right to deprive the country of their services." Goodwin described the group in her biography of Lincoln as a " team of rivals". Lincoln named his main political opponent, William H. Seward

William Henry Seward (; May 16, 1801 – October 10, 1872) was an American politician who served as United States Secretary of State from 1861 to 1869, and earlier served as governor of New York and as a United States senator. A determined opp ...

, as Secretary of State.

Lincoln made five appointments to the Supreme Court. Noah Haynes Swayne, a prominent corporate lawyer from Ohio, replaced John McLean

John McLean (March 11, 1785 – April 4, 1861) was an American jurist and politician who served in the United States Congress, as U.S. Postmaster General, and as a justice of the Ohio and United States Supreme Courts. He was often discu ...

after the latter's death in April 1861. Like McLean, Swayne opposed slavery. Samuel Freeman Miller

Samuel Freeman Miller (April 5, 1816 – October 13, 1890) was an American lawyer and physician who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, associate justice of the United States Supreme Court, U.S. Supreme ...

, who replaced Peter V. Daniel, was an avowed abolitionist and received widespread support from Iowa politicians. David Davis was Lincoln's campaign manager in 1860 and had served as a judge in the Illinois court circuit where Lincoln practiced. Democrat Stephen Johnson Field

Stephen Johnson Field (November 4, 1816 – April 9, 1899) was an American jurist. He was an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court from May 20, 1863, to December 1, 1897, the second longest tenure of any justice. Prior to this ap ...

, a previous California Supreme Court justice, provided geographic and political balance. Finally, after the death of Roger B. Taney

Roger Brooke Taney ( ; March 17, 1777 – October 12, 1864) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the fifth Chief Justice of the United States, chief justice of the United States, holding that office from 1836 until his death in 186 ...

, Lincoln appointed his secretary of the treasury, Salmon P. Chase

Salmon Portland Chase (January 13, 1808May 7, 1873) was an American politician and jurist who served as the sixth chief justice of the United States from 1864 to his death in 1873. Chase served as the 23rd governor of Ohio from 1856 to 1860, r ...

, to replace Taney as chief justice. Lincoln believed Chase was an able jurist who would support Reconstruction legislation and that his appointment would unite the Republican Party.

Commander-in-Chief

In early April 1861, Major Robert Anderson, commander of

In early April 1861, Major Robert Anderson, commander of Fort Sumter

Fort Sumter is a historical Coastal defense and fortification#Sea forts, sea fort located near Charleston, South Carolina. Constructed on an artificial island at the entrance of Charleston Harbor in 1829, the fort was built in response to the W ...

in Charleston, South Carolina, advised that he was nearly out of food. After considerable debate, Lincoln decided to send provisions; according to Michael Burlingame, he "could not be sure that his decision would precipitate a war, though he had good reason to believe that it might". On April 12, 1861, Confederate forces fired on Union troops at Fort Sumter. Donald concludes: His repeated efforts to avoid collision in the months between inauguration and the firing on Fort Sumter showed he adhered to his vow not to be the first to shed fraternal blood. But he had also vowed not to surrender the forts.... The only resolution of these contradictory positions was for the Confederates to fire the first shot.

The April 12 and 13 attack on Fort Sumter rallied the people of the North to support military action against the South to defend the nation. On April 15, Lincoln called for 75,000 militiamen to recapture forts, protect Washington, and preserve the Union. This call forced states to choose whether to secede or to support the Union. North Carolina, Virginia, Tennessee, and Arkansas seceded. As the Northern states sent regiments south, on April 19 Baltimore mobs in control of the rail links attacked Union troops who were changing trains. Local leaders' groups later burned critical rail bridges to the capital and the Army responded by arresting local Maryland officials. Lincoln suspended the writ of ''habeas corpus

''Habeas corpus'' (; from Medieval Latin, ) is a legal procedure invoking the jurisdiction of a court to review the unlawful detention or imprisonment of an individual, and request the individual's custodian (usually a prison official) to ...

'', allowing arrests without formal charges.

John Merryman

John Merryman (August 9, 1824 – November 15, 1881) of Baltimore County, Maryland, was arrested in May 1861 and held prisoner in Fort McHenry in Baltimore and was the petitioner in the case ''" Ex parte Merryman"'' which was one of the best kno ...

, a Maryland officer arrested for hindering U.S. troop movements, successfully petitioned Supreme Court Chief Justice Taney to issue a writ of ''habeas corpus''. In a written opinion titled ''Ex parte Merryman

''Ex parte Merryman'', 17 F. Cas. 144 (C.C.D. Md. 1861) (No. 9487), was a controversial U.S. federal court case during the American Civil War. It was a test of the authority of the President to suspend "the privilege of the wri ...

'', Taney, not ruling on behalf of the Supreme Court, held that the Constitution authorized only Congress and not the president to suspend habeas corpus. But Lincoln engaged in nonacquiescence

In law, nonacquiescence is the intentional failure by one branch of the government to comply with the decision of another to some degree. It tends to arise only in governments that feature a strong separation of powers, such as in the United State ...

and persisted with the policy of suspension in select areas. Under various suspensions, 15,000 civilians were detained without trial; several, including the anti-war Democrat Clement L. Vallandigham, were tried in military courts for "treasonable" actions, an approach that was highly criticized.[

]

Early Union military strategy

Lincoln took executive control of the war and shaped the Union military strategy. He responded to the unprecedented political and military crisis as commander-in-chief by exercising unprecedented authority. He expanded his war powers, imposed a naval blockade

A navy, naval force, military maritime fleet, war navy, or maritime force is the branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral, or ocean-borne combat operations ...

on Confederate ports, disbursed funds before appropriation by Congress, suspended ''habeas corpus'', and arrested and imprisoned thousands of suspected Confederate sympathizers. Lincoln gained the support of Congress and the northern public for these actions. Lincoln also had to reinforce Union sympathies in the border slave states and keep the war from becoming an international conflict.

It was clear from the outset that bipartisan support was essential to success, and that any compromise alienated factions in both political parties. Copperheads (anti-war Democrats) criticized Lincoln for refusing to compromise on slavery; the Radical Republicans

The Radical Republicans were a political faction within the Republican Party originating from the party's founding in 1854—some six years before the Civil War—until the Compromise of 1877, which effectively ended Reconstruction. They ca ...

(who demanded harsh treatment against secession) criticized him for moving too slowly in abolishing slavery. On August 6, 1861, Lincoln signed the Confiscation Act

The Confiscation Acts were laws passed by the United States Congress during the Civil War with the intention of freeing the slaves still held by the Confederate forces in the South.

The Confiscation Act of 1861 authorized the confiscation of any C ...

, which authorized judicial proceedings to confiscate and free slaves who were used to support the Confederates. The law had little practical effect, but it signaled political support for abolishing slavery.

Lincoln's war strategy had two priorities: ensuring that Washington was well defended and conducting an aggressive war effort for a prompt, decisive victory. Twice a week, Lincoln met with his cabinet. Occasionally, Lincoln's wife, Mary, prevailed on him to take a carriage ride, concerned that he was working too hard. Early in the war, Lincoln selected civilian generals from varied political and ethnic backgrounds "to secure their and their constituents' support for the war effort and ensure that the war became a national struggle". In January 1862, after complaints of inefficiency and profiteering in the War Department, Lincoln replaced

Lincoln's war strategy had two priorities: ensuring that Washington was well defended and conducting an aggressive war effort for a prompt, decisive victory. Twice a week, Lincoln met with his cabinet. Occasionally, Lincoln's wife, Mary, prevailed on him to take a carriage ride, concerned that he was working too hard. Early in the war, Lincoln selected civilian generals from varied political and ethnic backgrounds "to secure their and their constituents' support for the war effort and ensure that the war became a national struggle". In January 1862, after complaints of inefficiency and profiteering in the War Department, Lincoln replaced War Secretary

The secretary of state for war, commonly called the war secretary, was a secretary of state in the Government of the United Kingdom, which existed from 1794 to 1801 and from 1854 to 1964. The secretary of state for war headed the War Offic ...

Simon Cameron with Edwin Stanton

Edwin McMasters Stanton (December 19, 1814December 24, 1869) was an American lawyer and politician who served as U.S. Secretary of War, U.S. secretary of war under the Lincoln Administration during most of the American Civil War. Stanton's manag ...

. Stanton worked more often and more closely with Lincoln than did any other senior official. According to Stanton's biographers Benjamin Thomas and Harold Hyman, "Stanton and Lincoln virtually conducted the war together".

For his edification Lincoln relied on a book by Henry Halleck

Henry Wager Halleck (January 16, 1815 – January 9, 1872) was a senior United States Army officer, scholar, and lawyer. A noted expert in military studies, he was known by a nickname that became derogatory: "Old Brains". He was an important part ...

, ''Elements of Military Art and Science''. Lincoln began to appreciate the critical need to control strategic points, such as the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the main stem, primary river of the largest drainage basin in the United States. It is the second-longest river in the United States, behind only the Missouri River, Missouri. From its traditional source of Lake Ita ...

. Lincoln saw the importance of Vicksburg and understood the necessity of defeating the enemy's army, rather than merely capturing territory. In directing the Union's war strategy, Lincoln valued the advice of Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott (June 13, 1786May 29, 1866) was an American military commander and political candidate. He served as Commanding General of the United States Army from 1841 to 1861, and was a veteran of the War of 1812, American Indian Wars, Mexica ...

, even after his retirement as Commanding General of the United States Army

Commanding General of the United States Army was the title given to the service chief and highest-ranking officer of the United States Army (and its predecessor the Continental Army), prior to the establishment of the Chief of Staff of the Unit ...

. In 1861 Scott proposed the Anaconda Plan

The Anaconda Plan was a strategy outlined by the Union Army for suppressing the Confederacy at the beginning of the American Civil War. Proposed by Union General-in-Chief Winfield Scott, the plan emphasized a Union blockade of the Southern port ...

, which relied on port blockades and advancing down the Mississippi to subdue the South. In June 1862, Lincoln made an unannounced visit to West Point

The United States Military Academy (USMA), commonly known as West Point, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York that educates cadets for service as Officer_(armed_forces)#United_States, comm ...

, where he spent five hours consulting with Scott regarding the handling of the war.

Internationally, Lincoln wanted to forestall foreign military aid to the Confederacy. He relied on his combative Secretary of State William Seward while working closely with Senate Foreign Relations Committee

The United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations is a standing committee of the U.S. Senate charged with leading foreign-policy legislation and debate in the Senate. It is generally responsible for authorizing and overseeing foreign a ...

chairman Charles Sumner

Charles Sumner (January 6, 1811March 11, 1874) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented Massachusetts in the United States Senate from 1851 until his death in 1874. Before and during the American Civil War, he was a leading American ...

. In 1861 the U.S. Navy illegally intercepted a British mail ship, the ''RMS Trent

RMS ''Trent'' was a British Royal Mail paddle steamer built in 1841 by William Pitcher of Northfleet for the Royal Mail Steam Packet Company. She measured 1,856 gross tons and could carry 60 passengers. She was one of four ships constructed ...

'', on the high seas and seized two Confederate envoys. Although the North celebrated the seizure, Britain protested vehemently, and the Trent Affair threatened war between the Americans and the British. Lincoln ended the crisis by releasing the two diplomats.

McClellan

After the Union rout at Bull Run and Winfield Scott's retirement, Lincoln appointed George B. McClellan

George Brinton McClellan (December 3, 1826 – October 29, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 24th governor of New Jersey and as Commanding General of the United States Army from November 1861 to March 186 ...

general-in-chief. Early in the war, McClellan created defenses for Washington that were almost impregnable: 48 forts and batteries, with 480 guns manned by 7,200 artillerists. He spent months planning his Virginia Peninsula Campaign

The Peninsula campaign (also known as the Peninsular campaign) of the American Civil War was a major Union operation launched in southeastern Virginia from March to July 1862, the first large-scale offensive in the Eastern Theater. The oper ...

. McClellan's slow progress and excessive precautions frustrated Lincoln. McClellan, in turn, blamed the failure of the campaign on Lincoln's cautiousness in having reserved troops for the capital. In 1862, Lincoln removed McClellan as general-in-chief because of the latter's continued inaction. He elevated Henry Halleck to the post and appointed John Pope as head of the new Army of Virginia

The Army of Virginia was organized as a major unit of the Union Army and operated briefly and unsuccessfully in 1862 in the American Civil War. It should not be confused with its principal opponent, the Confederate Army of ''Northern'' Virginia ...

. But in the summer of 1862 Pope was soundly defeated at the Second Battle of Bull Run

The Second Battle of Bull Run or Battle of Second Manassas was fought August 28–30, 1862, in Prince William County, Virginia, as part of the American Civil War. It was the culmination of the Northern Virginia Campaign waged by Confederate ...

, forcing him to retreat to Washington. Soon after, the Army of Virginia was disbanded.

Despite his dissatisfaction with McClellan's failure to reinforce Pope, Lincoln restored him to command of all forces around Washington, which included both the Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the primary field army of the Union army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was created in July 1861 shortly after the First Battle of Bull Run and was disbanded in June 1865 following the Battle of ...

and the remains of the Army of Virginia. Two days later, Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was a general officers in the Confederate States Army, Confederate general during the American Civil War, who was appointed the General in Chief of the Armies of the Confederate ...

's forces crossed the Potomac River