A. afarensis on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Australopithecus afarensis'' is an

In 1978, Johanson,

In 1978, Johanson,  ''A. afarensis'' is known only from

''A. afarensis'' is known only from

Like other australopiths, the ''A. afarensis'' skeleton exhibits a mosaic anatomy with some aspects similar to modern humans and others to non-human great apes. The pelvis and leg bones clearly indicate weight-bearing ability, equating to habitual bipedal, but the upper limbs are reminiscent of orangutans, which would indicate

Like other australopiths, the ''A. afarensis'' skeleton exhibits a mosaic anatomy with some aspects similar to modern humans and others to non-human great apes. The pelvis and leg bones clearly indicate weight-bearing ability, equating to habitual bipedal, but the upper limbs are reminiscent of orangutans, which would indicate

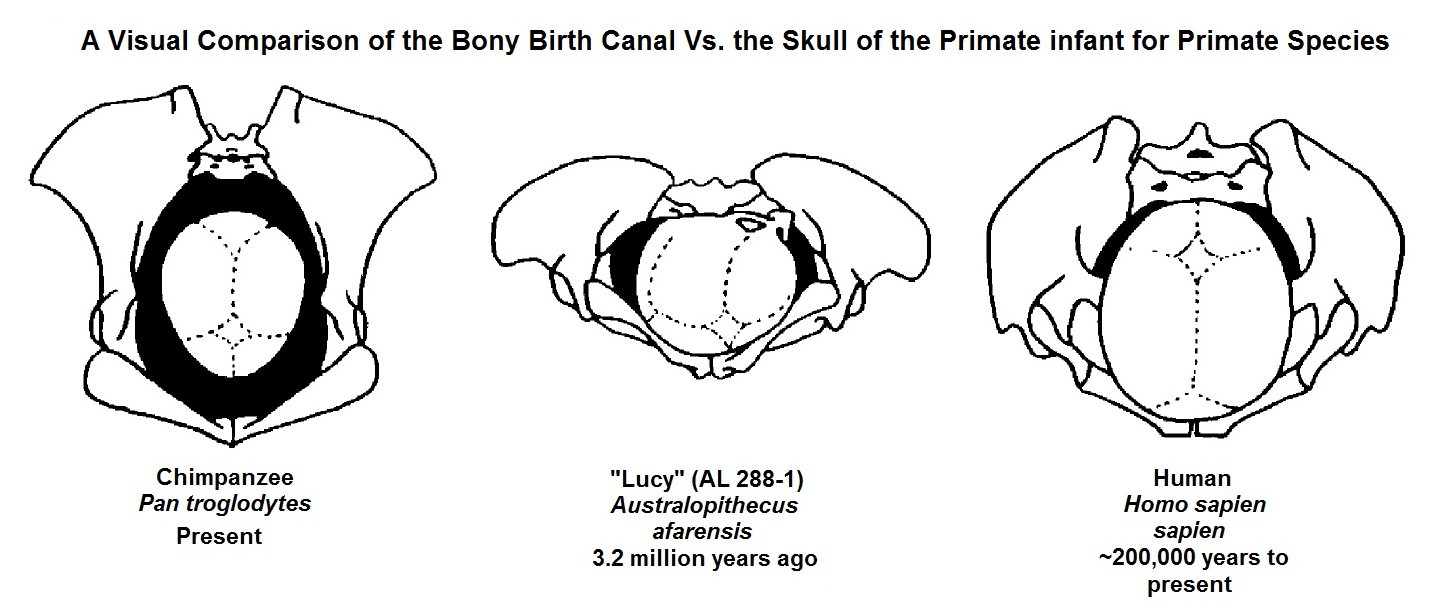

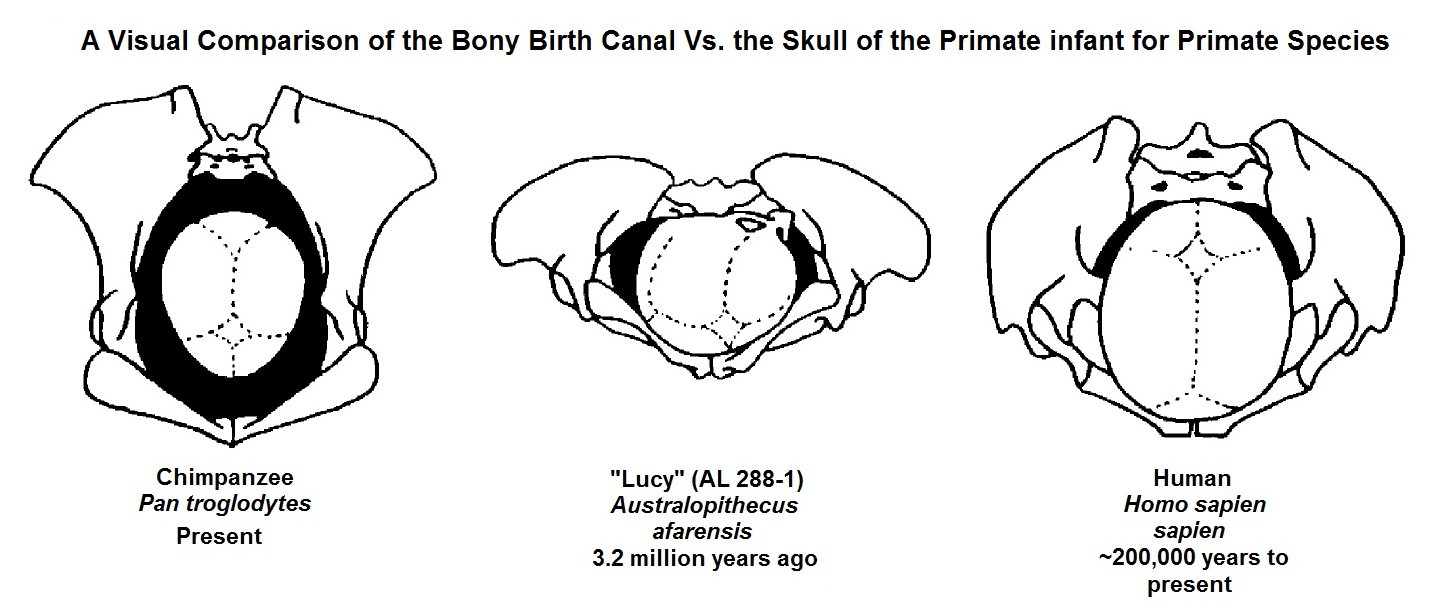

The platypelloid pelvis may have caused a different birthing mechanism from modern humans, with the

The platypelloid pelvis may have caused a different birthing mechanism from modern humans, with the

Becoming Human: Paleoanthropology, Evolution and Human Origins

The Smithsonian's Human Origins Program

Human Timeline (Interactive)

– Smithsonian {{Authority control afarensis Pliocene primates Mammals described in 1978 Fossil taxa described in 1978 Prehistoric Ethiopia Prehistoric Kenya Pliocene mammals of Africa Tool-using mammals Taxa named by Donald Johanson Taxa named by Tim D. White Archaeology of Eastern Africa

extinct

Extinction is the termination of a kind of organism or of a group of kinds (taxon), usually a species. The moment of extinction is generally considered to be the death of the last individual of the species, although the capacity to breed and ...

species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate s ...

of australopithecine

Australopithecina or Hominina is a subtribe in the tribe Hominini. The members of the subtribe are generally ''Australopithecus'' (cladistically including the genus, genera ''Homo'', ''Paranthropus'', and ''Kenyanthropus''), and it typically in ...

which lived from about 3.9–2.9 million years ago (mya) in the Pliocene

The Pliocene ( ; also Pleiocene) is the epoch in the geologic time scale that extends from 5.333 million to 2.58East Africa

East Africa, Eastern Africa, or East of Africa, is the eastern subregion of the African continent. In the United Nations Statistics Division scheme of geographic regions, 10-11-(16*) territories make up Eastern Africa:

Due to the historical ...

. The first fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

s were discovered in the 1930s, but major fossil finds would not take place until the 1970s. From 1972 to 1977, the International Afar Research Expedition—led by anthropologists Maurice Taieb

Maurice Taieb (22 July 1935 – 23 July 2021) was a French geologist and paleoanthropologist. He discovered the Hadar formation, recognized its potential importance to paleoanthropology and founded the International Afar Research Expedition (I ...

, Donald Johanson

Donald Carl Johanson (born June 28, 1943) is an American paleoanthropologist. He is known for discovering, with Yves Coppens and Maurice Taieb, the fossil of a female hominin australopithecine known as "Lucy" in the Afar Triangle region of Hada ...

and Yves Coppens

Yves Coppens (9 August 1934 – 22 June 2022) was a French anthropologist. A graduate from the University of Rennes and Sorbonne, he studied ancient hominids and had multiple published works on this topic, and also produced a film. In October 2 ...

—unearthed several hundreds of hominin

The Hominini form a taxonomic tribe of the subfamily Homininae ("hominines"). Hominini includes the extant genera ''Homo'' (humans) and '' Pan'' (chimpanzees and bonobos) and in standard usage excludes the genus ''Gorilla'' (gorillas).

The t ...

specimens in Hadar, Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the ...

, the most significant being the exceedingly well-preserved skeleton AL 288-1 ("Lucy

Lucy is an English feminine given name derived from the Latin masculine given name Lucius with the meaning ''as of light'' (''born at dawn or daylight'', maybe also ''shiny'', or ''of light complexion''). Alternative spellings are Luci, Luce, Lu ...

") and the site AL 333

AL 333, commonly referred to as the "First Family", is a collection of prehistoric hominid teeth and bones. Discovered in 1975 by Donald Johanson's team in Hadar, Ethiopia, the "First Family" is estimated to be about 3.2 million years old, and con ...

("the First Family"). Beginning in 1974, Mary Leakey

Mary Douglas Leakey, FBA (née Nicol, 6 February 1913 – 9 December 1996) was a British paleoanthropologist who discovered the first fossilised ''Proconsul

A proconsul was an official of ancient Rome who acted on behalf of a consul. A pro ...

led an expedition into Laetoli

Laetoli is a pre-historic site located in Enduleni ward of Ngorongoro District in Arusha Region, Tanzania. The site is dated to the Plio-Pleistocene and famous for its Hominina footprints, preserved in volcanic ash. The site of the Laetoli fo ...

, Tanzania

Tanzania (; ), officially the United Republic of Tanzania ( sw, Jamhuri ya Muungano wa Tanzania), is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It borders Uganda to the north; Kenya to the northeast; Comoro Islands and ...

, and notably recovered fossil trackway

A fossil track or ichnite (Greek "''ιχνιον''" (''ichnion'') – a track, trace or footstep) is a fossilized footprint. This is a type of trace fossil. A fossil trackway is a sequence of fossil tracks left by a single organism. Over the year ...

s. In 1978, the species was first described, but this was followed by arguments for splitting the wealth of specimens into different species given the wide range of variation which had been attributed to sexual dimorphism

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where the sexes of the same animal and/or plant species exhibit different morphological characteristics, particularly characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. The condition occurs in most ani ...

(normal differences between males and females). ''A. afarensis'' probably descended from '' A. anamensis'' and is hypothesised to have given rise to ''Homo

''Homo'' () is the genus that emerged in the (otherwise extinct) genus ''Australopithecus'' that encompasses the extant species ''Homo sapiens'' ( modern humans), plus several extinct species classified as either ancestral to or closely relate ...

'', though the latter is debated.

''A. afarensis'' had a tall face, a delicate brow ridge, and prognathism (the jaw jutted outwards). The jawbone was quite robust

Robustness is the property of being strong and healthy in constitution. When it is transposed into a system, it refers to the ability of tolerating perturbations that might affect the system’s functional body. In the same line ''robustness'' ca ...

, similar to that of gorilla

Gorillas are herbivorous, predominantly ground-dwelling great apes that inhabit the tropical forests of equatorial Africa. The genus ''Gorilla'' is divided into two species: the eastern gorilla and the western gorilla, and either four or fi ...

s. The living size of ''A. afarensis'' is debated, with arguments for and against marked size differences between males and females. Lucy measured perhaps in height and , but she was rather small for her species. In contrast, a presumed male was estimated at and . A perceived difference in male and female size may simply be sampling bias

In statistics, sampling bias is a bias in which a sample is collected in such a way that some members of the intended population have a lower or higher sampling probability than others. It results in a biased sample of a population (or non-human fa ...

. The leg bones as well as the Laetoli fossil trackways suggest ''A. afarensis'' was a competent biped

Bipedalism is a form of terrestrial locomotion where an organism moves by means of its two rear limbs or legs. An animal or machine that usually moves in a bipedal manner is known as a biped , meaning 'two feet' (from Latin ''bis'' 'double' a ...

, though somewhat less efficient at walking than humans. The arm and shoulder bones have some similar aspects to those of orangutan

Orangutans are great apes native to the rainforests of Indonesia and Malaysia. They are now found only in parts of Borneo and Sumatra, but during the Pleistocene they ranged throughout Southeast Asia and South China. Classified in the genus ...

s and gorillas, which has variously been interpreted as either evidence of partial tree-dwelling (arboreal

Arboreal locomotion is the Animal locomotion, locomotion of animals in trees. In habitats in which trees are present, animals have evolved to move in them. Some animals may scale trees only occasionally, but others are exclusively arboreal. Th ...

ity), or basal traits inherited from the chimpanzee–human last common ancestor

The chimpanzee–human last common ancestor (CHLCA) is the last common ancestor shared by the extant ''Homo'' (human) and '' Pan'' (chimpanzee and bonobo) genera of Hominini. Due to complex hybrid speciation, it is not currently possible to give ...

with no adaptive functionality.

''A. afarensis'' was probably a generalist

A generalist is a person with a wide array of knowledge on a variety of subjects, useful or not. It may also refer to:

Occupations

* a physician who provides general health care, as opposed to a medical specialist; see also:

** General pract ...

omnivore

An omnivore () is an animal that has the ability to eat and survive on both plant and animal matter. Obtaining energy and nutrients from plant and animal matter, omnivores digest carbohydrates, protein, fat, and fiber, and metabolize the nutr ...

of both C3 forest plants and C4 CAM

Calmodulin (CaM) (an abbreviation for calcium-modulated protein) is a multifunctional intermediate calcium-binding messenger protein expressed in all eukaryotic cells. It is an intracellular target of the secondary messenger Ca2+, and the bin ...

savanna plants—and perhaps creatures which ate such plants—and was able to exploit a variety of different food sources. Similarly, ''A. afarensis'' appears to have inhabited a wide range of habitats with no real preference, inhabiting open grasslands or woodlands, shrublands, and lake- or riverside forests. Potential evidence of stone tool

A stone tool is, in the most general sense, any tool made either partially or entirely out of stone. Although stone tool-dependent societies and cultures still exist today, most stone tools are associated with prehistoric (particularly Stone Ag ...

use would indicate meat was also a dietary component. Marked sexual dimorphism in primates typically corresponds to a polygynous

Polygyny (; from Neoclassical Greek πολυγυνία (); ) is the most common and accepted form of polygamy around the world, entailing the marriage of a man with several women.

Incidence

Polygyny is more widespread in Africa than in any ...

society and low dimorphism to monogamy

Monogamy ( ) is a form of dyadic relationship in which an individual has only one partner during their lifetime. Alternately, only one partner at any one time (serial monogamy) — as compared to the various forms of non-monogamy (e.g., polyga ...

, but the group dynamics of early hominins is difficult to predict with accuracy. Early hominins may have fallen prey to the large carnivores of the time, such as big cat

The term "big cat" is typically used to refer to any of the five living members of the genus '' Panthera'', namely the tiger, lion, jaguar, leopard, and snow leopard.

Despite enormous differences in size, various cat species are quite similar ...

s and hyena

Hyenas, or hyaenas (from Ancient Greek , ), are feliform carnivoran mammals of the family Hyaenidae . With only four extant species (each in its own genus), it is the fifth-smallest family in the Carnivora and one of the smallest in the clas ...

s.

Taxonomy

Research history

Beginning in the 1930s, some of the most ancienthominin

The Hominini form a taxonomic tribe of the subfamily Homininae ("hominines"). Hominini includes the extant genera ''Homo'' (humans) and '' Pan'' (chimpanzees and bonobos) and in standard usage excludes the genus ''Gorilla'' (gorillas).

The t ...

remains of the time dating to 3.8–2.9 million years ago were recovered from East Africa. Because ''Australopithecus africanus

''Australopithecus africanus'' is an extinct species of australopithecine which lived between about 3.3 and 2.1 million years ago in the Late Pliocene to Early Pleistocene of South Africa. The species has been recovered from Taung, Sterkfonte ...

'' fossils were commonly being discovered throughout the 1920s and '40s in South Africa, these remains were often provisionally classified as ''Australopithecus'' aff. ''africanus''. The first to identify a human fossil was German explorer Ludwig Kohl-Larsen

Ludwig Kohl-Larsen (born ''Ludwig Kohl''; 5 April 1884 in Landau in der Pfalz – 12 November 1969 in Bodensee) was a German physician, amateur anthropologist, and explorer.

Biography

In 1911, he traveled as ship's doctor with Wilhelm Filchne ...

in 1939 by the headwaters of the Gerusi River (near Laetoli

Laetoli is a pre-historic site located in Enduleni ward of Ngorongoro District in Arusha Region, Tanzania. The site is dated to the Plio-Pleistocene and famous for its Hominina footprints, preserved in volcanic ash. The site of the Laetoli fo ...

, Tanzania), who encountered a maxilla

The maxilla (plural: ''maxillae'' ) in vertebrates is the upper fixed (not fixed in Neopterygii) bone of the jaw formed from the fusion of two maxillary bones. In humans, the upper jaw includes the hard palate in the front of the mouth. The t ...

. In 1948, German palaeontologist Edwin Hennig

Edwin Hennig (27 April 1882 – 12 November 1977) was a German paleontologist.

Career

Edwin Hennig was one of five children of a merchant who died when Hennig was 10 years old. Starting in 1902, Hennig studied natural sciences, anthropolog ...

proposed classifying it into a new genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus com ...

, "''Praeanthropus''", but he failed to give a species name. In 1950, German anthropologist Hans Weinert

Hans may refer to:

__NOTOC__ People

* Hans (name), a masculine given name

* Hans Raj Hans, Indian singer and politician

** Navraj Hans, Indian singer, actor, entrepreneur, cricket player and performer, son of Hans Raj Hans

** Yuvraj Hans, Punjabi a ...

proposed classifying it as ''Meganthropus africanus'', but this was largely ignored. In 1955, M.S. Şenyürek proposed the combination ''Praeanthropus africanus''. Major collections were made in Laetoli

Laetoli is a pre-historic site located in Enduleni ward of Ngorongoro District in Arusha Region, Tanzania. The site is dated to the Plio-Pleistocene and famous for its Hominina footprints, preserved in volcanic ash. The site of the Laetoli fo ...

, Tanzania, on an expedition beginning in 1974 directed by British palaeoanthropologist Mary Leakey

Mary Douglas Leakey, FBA (née Nicol, 6 February 1913 – 9 December 1996) was a British paleoanthropologist who discovered the first fossilised ''Proconsul

A proconsul was an official of ancient Rome who acted on behalf of a consul. A pro ...

, and in Hadar, Ethiopia, from 1972 to 1977 by the International Afar Research Expedition (IARE) formed by French geologist Maurice Taieb

Maurice Taieb (22 July 1935 – 23 July 2021) was a French geologist and paleoanthropologist. He discovered the Hadar formation, recognized its potential importance to paleoanthropology and founded the International Afar Research Expedition (I ...

, American palaeoanthropologist Donald Johanson

Donald Carl Johanson (born June 28, 1943) is an American paleoanthropologist. He is known for discovering, with Yves Coppens and Maurice Taieb, the fossil of a female hominin australopithecine known as "Lucy" in the Afar Triangle region of Hada ...

and Breton anthropologist Yves Coppens

Yves Coppens (9 August 1934 – 22 June 2022) was a French anthropologist. A graduate from the University of Rennes and Sorbonne, he studied ancient hominids and had multiple published works on this topic, and also produced a film. In October 2 ...

. These fossils were remarkably well preserved and many had associated skeletal aspects. In 1973, the IARE team unearthed the first knee joint

In humans and other primates, the knee joins the thigh with the leg and consists of two joints: one between the femur and tibia (tibiofemoral joint), and one between the femur and patella (patellofemoral joint). It is the largest joint in the hu ...

, AL 129-1, and showed the earliest example at the time of bipedalism

Bipedalism is a form of terrestrial locomotion where an organism moves by means of its two rear limbs or legs. An animal or machine that usually moves in a bipedal manner is known as a biped , meaning 'two feet' (from Latin ''bis'' 'double' a ...

. In 1974, Johanson and graduate student Tom Gray discovered the extremely well-preserved skeleton AL 288–1, commonly referred to as "Lucy

Lucy is an English feminine given name derived from the Latin masculine given name Lucius with the meaning ''as of light'' (''born at dawn or daylight'', maybe also ''shiny'', or ''of light complexion''). Alternative spellings are Luci, Luce, Lu ...

" (named after the 1967 Beatles

The Beatles were an English rock band, formed in Liverpool in 1960, that comprised John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr. They are regarded as the most influential band of all time and were integral to the developme ...

song ''Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds

"Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds" is a song by the English rock band the Beatles from their 1967 album '' Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band''. It was written primarily by John Lennon and credited to the Lennon–McCartney songwriting partners ...

'' which was playing on their tape recorder

An audio tape recorder, also known as a tape deck, tape player or tape machine or simply a tape recorder, is a sound recording and reproduction device that records and plays back sounds usually using magnetic tape for storage. In its present- ...

that evening). In 1975, the IARE recovered 216 specimens belonging to 13 individuals, AL 333

AL 333, commonly referred to as the "First Family", is a collection of prehistoric hominid teeth and bones. Discovered in 1975 by Donald Johanson's team in Hadar, Ethiopia, the "First Family" is estimated to be about 3.2 million years old, and con ...

"the First Family" (though the individuals were not necessarily related). In 1976, Leakey and colleagues discovered fossil trackway

A fossil track or ichnite (Greek "''ιχνιον''" (''ichnion'') – a track, trace or footstep) is a fossilized footprint. This is a type of trace fossil. A fossil trackway is a sequence of fossil tracks left by a single organism. Over the year ...

s, and preliminarily classified Laetoli remains into ''Homo

''Homo'' () is the genus that emerged in the (otherwise extinct) genus ''Australopithecus'' that encompasses the extant species ''Homo sapiens'' ( modern humans), plus several extinct species classified as either ancestral to or closely relate ...

'' spp., attributing ''Australopithecus''-like traits as evidence of them being transitional fossil

A transitional fossil is any fossilized remains of a life form that exhibits traits common to both an ancestral group and its derived descendant group. This is especially important where the descendant group is sharply differentiated by gross a ...

s.

In 1978, Johanson,

In 1978, Johanson, Tim D. White

Tim D. White (born August 24, 1950) is an American paleoanthropologist and Professor of Integrative Biology at the University of California, Berkeley. He is best known for leading the team which discovered Ardi, the type specimen of ''Ardipithe ...

and Coppens classified the hundreds of specimens collected thus far from both Hadar and Laetoli into a single new species, ''A. afarensis'', and considered the apparently wide range of variation a result of sexual dimorphism

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where the sexes of the same animal and/or plant species exhibit different morphological characteristics, particularly characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. The condition occurs in most ani ...

. The species name

In taxonomy, binomial nomenclature ("two-term naming system"), also called nomenclature ("two-name naming system") or binary nomenclature, is a formal system of naming species of living things by giving each a name composed of two parts, bot ...

honours the Afar Region

The Afar Region (; aa, Qafar Rakaakayak; am, አፋር ክልል), formerly known as Region 2, is a regional state in northeastern Ethiopia and the homeland of the Afar people. Its capital is the planned city of Semera, which lies on the paved ...

of Ethiopia where the majority of the specimens had been recovered from. They later selected the jawbone LH 4 as the lectotype specimen

In biology, a type is a particular specimen (or in some cases a group of specimens) of an organism to which the scientific name of that organism is formally attached. In other words, a type is an example that serves to anchor or centralizes t ...

because of its preservation quality and because White had already fully described and illustrated it the year before.

''A. afarensis'' is known only from

''A. afarensis'' is known only from East Africa

East Africa, Eastern Africa, or East of Africa, is the eastern subregion of the African continent. In the United Nations Statistics Division scheme of geographic regions, 10-11-(16*) territories make up Eastern Africa:

Due to the historical ...

. Beyond Laetoli and the Afar Region, the species has been recorded in Kenya at Koobi Fora

Koobi Fora refers primarily to a region around Koobi Fora Ridge, located on the eastern shore of Lake Turkana in the territory of the nomadic Gabbra people. According to the National Museums of Kenya, the name comes from the Gabbra language:

...

and possibly Lothagam

Lothagam is a geological formation located in Kenya, near the southwestern shores of Lake Turkana, from Kanapoi. It is located between the Kerio and Lomunyenkuparet Rivers on an uplifted fault block. Lothagam has deposits dating to the Miocene- ...

; and elsewhere in Ethiopia at Woranso-Mille, Maka, Belohdelie, Ledi-Geraru

Ledi-Geraru is a paleoanthropological research area in Mille district, Afar Region, northeastern Ethiopia, along the Ledi and Geraru rivers (two left tributaries of the Awash, south of the Mille river). It stretches for about 50 km, lo ...

and Fejej. The frontal bone

The frontal bone is a bone in the human skull. The bone consists of two portions.''Gray's Anatomy'' (1918) These are the vertically oriented squamous part, and the horizontally oriented orbital part, making up the bony part of the forehead, par ...

fragment BEL-VP-1/1 from the Middle Awash

The Middle Awash is a paleoanthropological research area in the Afar Region along the Awash River in Ethiopia's Afar Depression. It is a unique natural laboratory for the study of human origins and evolution and a number of fossils of the earliest ...

, Afar Region, Ethiopia, dating to 3.9 million years ago has typically been assigned to ''A. anamensis'' based on age, but may be assignable to ''A. afarensis'' because it exhibits a derived

Derive may refer to:

* Derive (computer algebra system), a commercial system made by Texas Instruments

* ''Dérive'' (magazine), an Austrian science magazine on urbanism

*Dérive, a psychogeographical concept

See also

*

*Derivation (disambiguatio ...

form of postorbital constriction

In physical anthropology, post-orbital constriction is the narrowing of the cranium (skull) just behind the eye sockets (the orbits, hence the name) found in most non-human primates and early hominins. This constriction is very noticeable in non-h ...

. This would mean ''A. afarensis'' and ''A. anamensis'' coexisted for at least 100,000 years. In 2005, a second adult specimen preserving both skull and body elements, AL 438–1, was discovered in Hadar. In 2006, an infant partial skeleton, DIK-1-1

Selam (DIK-1/1) is the fossilized skull and other skeletal remains of a three-year-old ''Australopithecus afarensis'' female hominin, whose bones were first found in Dikika, Ethiopia in 2000 and recovered over the following years. Although she h ...

, was unearthed at Dikika

The Dikika is an area of the Afar Region of Ethiopia where the hominin fossil named Selam was found (a specimen of the '' Australopithecus afarensis'' species). Dikika is located in Mille woreda.Based on the map of the findsite printed in Alemse ...

, Afar Region. In 2015, an adult partial skeleton, KSD-VP-1/1, was recovered from Woranso-Mille.

For a long time, ''A. afarensis'' was the oldest known African great ape until the 1994 description of the 4.4-million-year-old ''Ardipithecus ramidus

''Ardipithecus ramidus'' is a species of australopithecine from the Afar region of Early Pliocene Ethiopia 4.4 million years ago (mya). ''A. ramidus'', unlike modern hominids, has adaptations for both walking on two legs ( bipedality) and life i ...

'', and a few earlier or contemporary taxa have been described since, including the 4-million-year-old ''A. anamensis'' in 1995, the 3.5-million-year-old ''Kenyanthropus platyops

''Kenyanthropus'' is a hominin genus identified from the Lomekwi site by Lake Turkana, Kenya, dated to 3.3 to 3.2 million years ago during the Middle Pliocene. It contains one species, ''K. platyops'', but may also include the 2 million year ol ...

'' in 2001, the 6-million-year-old ''Orrorin tugenensis

''Orrorin tugenensis'' is a postulated early species of Homininae, estimated at and discovered in 2000. It is not confirmed how ''Orrorin'' is related to modern humans. Its discovery was used to argue against the hypothesis that australopitheci ...

'' in 2001, and the 7- to 6-million-year-old ''Sahelanthropus tchadensis'' in 2002. Bipedalism was once thought to have evolved in australopithecines, but it is now thought to have begun evolving much earlier in habitually arboreal primates. The earliest claimed date for the beginnings of an upright spine and a primarily vertical body plan is 21.6 million years ago in the Early Miocene

The Early Miocene (also known as Lower Miocene) is a sub-epoch of the Miocene Epoch made up of two stages: the Aquitanian and Burdigalian stages.

The sub-epoch lasted from 23.03 ± 0.05 Ma to 15.97 ± 0.05 Ma (million years ago). It was prece ...

with '' Morotopithecus bishopi''.

Classification

''A. afarensis'' is now a widely accepted species, and it is now generally thought that ''Homo'' and ''Paranthropus'' aresister taxa

In phylogenetics, a sister group or sister taxon, also called an adelphotaxon, comprises the closest relative(s) of another given unit in an evolutionary tree.

Definition

The expression is most easily illustrated by a cladogram:

Taxon A and ...

deriving from ''Australopithecus'', but the classification of ''Australopithecus'' species is in disarray. ''Australopithecus'' is considered a grade taxon whose members are united by their similar physiology rather than close relations with each other over other hominin genera. It is unclear how any ''Australopithecus'' species relate to each other, but it is generally thought that a population of '' A. anamensis'' evolved into ''A. afarensis''.

In 1979, Johanson and White proposed that ''A. afarensis'' was the last common ancestor between ''Homo'' and ''Paranthropus

''Paranthropus'' is a genus of extinct hominin which contains two widely accepted species: ''Paranthropus robustus, P. robustus'' and ''P. boisei''. However, the validity of ''Paranthropus'' is contested, and it is sometimes considered to be sy ...

'', supplanting ''A. africanus'' in this role. Considerable debate of the validity of this species followed, with proposals for synonymising them with ''A. africanus'' or recognising multiple species from the Laetoli and Hadar remains. In 1980, South African palaeoanthropologist Phillip V. Tobias

Phillip Vallentine Tobias (14 October 1925 – 7 June 2012) was a South African palaeoanthropologist and Professor Emeritus at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. He was best known for his work at South Africa's hominid fossil ...

proposed reclassifying the Laetoli specimens as ''A. africanus afarensis'' and the Hadar specimens as ''A. afr. aethiopicus''. The skull KNM-ER 1470 (now ''H. rudolfensis

''Homo rudolfensis'' is an extinct species of archaic human from the Early Pleistocene of East Africa about 2 million years ago (mya). Because ''H. rudolfensis'' coexisted with several other hominins, it is debated what specimens can be confiden ...

'') was at first dated to 2.9 million years ago, which cast doubt on the ancestral position of both ''A. afarensis'' or ''A. africanus'', but it has been re-dated to about 2 million years ago. Several ''Australopithecus'' species have since been postulated to represent the ancestor to ''Homo'', but the 2013 discovery of the earliest ''Homo'' specimen, LD 350-1

LD 350-1 is the earliest known specimen of the genus ''Homo'', dating to 2.8–2.75 million years ago (mya), found in the Ledi-Geraru site in the Afar Region of Ethiopia. The specimen was discovered in silts above the Gurumaha Tuff section of the ...

, 2.8 million years old (older than almost all other ''Australopithecus'' species) from the Afar Region could potentially affirm ''A. afarensis'' ancestral position. However, ''A. afarensis'' is also argued to have been too derived (too specialised), due to resemblance in jaw anatomy to the robust australopithecines, to have been a human ancestor.

Palaeoartist Walter Ferguson has proposed splitting ''A. afarensis'' into "''H. antiquus''", a relict

A relict is a surviving remnant of a natural phenomenon.

Biology

A relict (or relic) is an organism that at an earlier time was abundant in a large area but now occurs at only one or a few small areas.

Geology and geomorphology

In geology, a r ...

dryopithecine

Dryopithecini is an extinct tribe of Eurasian and African great apes that are believed to be close to the ancestry of gorillas, chimpanzees and humans. Members of this tribe are known as dryopithecines.

Taxonomy

* Tribe Dryopithecini†

** ''Ke ...

"''Ramapithecus''" (now ''Kenyapithecus

''Kenyapithecus wickeri'' is a fossil ape discovered by Louis Leakey in 1961 at a site called Fort Ternan in Kenya. The upper jaw and teeth were dated to 14 million years ago.

One theory states that ''Kenyapithecus'' may be the common ances ...

'') and a subspecies of ''A. africanus''. His recommendations have largely been ignored. In 2003, Spanish writer Camilo José Cela Conde

Camilo José Arcadio Cela Conde, 2nd Marquess of Iria Flavia (born 17 January 1946), is a Spanish writer. He is the son of Nobel Prize in Literature, Nobel Prize winning writer Camilo José Cela and is currently a Professor (highest academic ran ...

and evolutionary biologist Francisco J. Ayala

Francisco José Ayala Pereda (born March 12, 1934) is a Spanish-American evolutionary biologist, philosopher, and former Catholic priest who was a longtime faculty member at the University of California, Irvine and University of California, Dav ...

proposed reinstating "''Praeanthropus''" including ''A. afarensis'' alongside ''Sahelanthropus

''Sahelanthropus tchadensis'' is an extinct species of the Homininae (African apes) dated to about , during the Miocene epoch. The species, and its genus ''Sahelanthropus'', was announced in 2002, based mainly on a partial cranium, nicknamed ''T ...

'', '' A. anamensis'', '' A. bahrelghazali'' and ''A. garhi

''Australopithecus garhi'' is a species of australopithecine from the Bouri Formation in the Afar Region of Ethiopia 2.6–2.5 million years ago (mya) during the Early Pleistocene. The first remains were described in 1999 based on several skele ...

''. In 2004, Danish biologist Bjarne Westergaard and geologist Niels Bonde proposed splitting off "''Homo hadar''" with the 3.2-million-year-old partial skull AL 333–45 as the holotype, because a foot from the First Family was apparently more humanlike than that of Lucy. In 2011, Bonde agreed with Ferguson that Lucy should be split into a new species, though erected a new genus as "''Afaranthropus antiquus''".

In 1996, a 3.6-million-year-old jaw from Koro Toro Koro Toro is a settlement in southern Borkou-Ennedi-Tibesti Region in Chad. It hosts the Koro Toro Airport and a "notorious" maximum security desert prison used by the Chadian government to detain captured fighters of Boko Haram and Chadian rebel ...

, Chad, originally classified as ''A. afarensis'' was split off into a new species as '' A. bahrelghazali''. In 2015, some 3.5- to 3.3-million-year-old jaw specimens from the Afar Region (the same time and place as ''A. afarensis'') were classified as a new species as '' A. deyiremeda'', and the recognition of this species would call into question the species designation of fossils currently assigned to ''A. afarensis''. However, the validity of ''A. bahrelghazali'' and ''A. deyiremeda'' is debated. Wood and Boyle (2016) stated there was "low confidence" that ''A. afarensis'', ''A. bahrelghazali'' and ''A. deyiremeda'' are distinct species, with ''Kenyanthropus platyops

''Kenyanthropus'' is a hominin genus identified from the Lomekwi site by Lake Turkana, Kenya, dated to 3.3 to 3.2 million years ago during the Middle Pliocene. It contains one species, ''K. platyops'', but may also include the 2 million year ol ...

'' perhaps being indistinct from the latter two.

Anatomy

Skull

''A. afarensis'' had a tall face, a delicate brow ridge, and prognathism (the jaw jutted outwards). One of the biggest skulls, AL 444–2, is about the size of a female gorilla skull. The first relatively complete jawbone was discovered in 2002, AL 822–1. This specimen strongly resembles the deep and robust gorilla jawbone. However, unlike gorillas, the strength of thesagittal

The sagittal plane (; also known as the longitudinal plane) is an anatomical plane that divides the body into right and left sections. It is perpendicular to the transverse and coronal planes. The plane may be in the center of the body and divid ...

and nuchal

The nape is the back of the neck. In technical anatomical/medical terminology, the nape is also called the nucha (from the Medieval Latin rendering of the Arabic , "spinal marrow"). The corresponding adjective is ''nuchal'', as in the term ''nu ...

crests (which support the temporalis muscle

In anatomy, the temporalis muscle, also known as the temporal muscle, is one of the muscles of mastication (chewing). It is a broad, fan-shaped convergent muscle on each side of the head that fills the temporal fossa, superior to the zygomati ...

used in biting) do not vary between sexes. The crests are similar to those of chimpanzees and female gorillas. Compared to earlier hominins, the incisor

Incisors (from Latin ''incidere'', "to cut") are the front teeth present in most mammals. They are located in the premaxilla above and on the mandible below. Humans have a total of eight (two on each side, top and bottom). Opossums have 18, whe ...

s of ''A. afarensis'' are reduced in breadth, the canines

Canine may refer to:

Zoology and anatomy

* a dog-like Canid animal in the subfamily Caninae

** ''Canis'', a genus including dogs, wolves, coyotes, and jackals

** Dog, the domestic dog

* Canine tooth, in mammalian oral anatomy

People with the surn ...

reduced in size and lost the honing mechanism which continually sharpens them, the premolar

The premolars, also called premolar teeth, or bicuspids, are transitional teeth located between the canine and molar teeth. In humans, there are two premolars per quadrant in the permanent set of teeth, making eight premolars total in the mouth ...

s are molar-shaped, and the molars are taller. The molars of australopiths are generally large and flat with thick enamel, which is ideal for crushing hard and brittle foods.

The brain volume of Lucy was estimated to have been 365–417 cc, specimen AL 822-1 about 374–392 cc, AL 333-45 about 486–492 cc, and AL 444-2 about 519–526 cc. This would make for an average of about 445 cc. The brain volumes of the infant (about 2.5 years of age) specimens DIK-1-1 and AL 333-105 are 273–277 and 310–315 cc, respectively. Using these measurements, the brain growth rate of ''A. afarensis'' was closer to the growth rate of modern humans than to the faster rate in chimpanzees. Though brain growth was prolonged, the duration was nonetheless much shorter than modern humans, which is why the adult ''A. afarensis'' brain was so much smaller. The ''A. afarensis'' brain was likely organised like non-human ape brains, with no evidence for humanlike brain configuration.

Size

''A. afarensis'' specimens apparently exhibit a wide range of variation, which is generally explained as marked sexual dimorphism with males much bigger than females. In 1991, American anthropologistHenry McHenry

Henry Malcolm McHenry (born May 19, 1944) is a professor of anthropology at the University of California, Davis, specializing in studies of human evolution, the origins of bipedality, and paleoanthropology.

McHenry has published on the comparativ ...

estimated body size by measuring the joint sizes of the leg bones and scaling down a human to meet that size. This yielded for a presumed male (AL 333–3), whereas Lucy was . In 1992, he estimated that males typically weighed about and females assuming body proportions were more humanlike than ape

Apes (collectively Hominoidea ) are a clade of Old World simians native to sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia (though they were more widespread in Africa, most of Asia, and as well as Europe in prehistory), which together with its sister g ...

like. This gives a male to female body mass ratio of 1.52, compared to 1.22 in modern human

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') are the most abundant and widespread species of primate, characterized by bipedalism and exceptional cognitive skills due to a large and complex brain. This has enabled the development of advanced tools, culture, ...

s, 1.37 in chimpanzee

The chimpanzee (''Pan troglodytes''), also known as simply the chimp, is a species of great ape native to the forest and savannah of tropical Africa. It has four confirmed subspecies and a fifth proposed subspecies. When its close relative th ...

s, and about 2 for gorilla

Gorillas are herbivorous, predominantly ground-dwelling great apes that inhabit the tropical forests of equatorial Africa. The genus ''Gorilla'' is divided into two species: the eastern gorilla and the western gorilla, and either four or fi ...

s and orangutan

Orangutans are great apes native to the rainforests of Indonesia and Malaysia. They are now found only in parts of Borneo and Sumatra, but during the Pleistocene they ranged throughout Southeast Asia and South China. Classified in the genus ...

s. However, this commonly cited weight figure used only three presumed-female specimens, of which two were among the smallest specimens recorded for the species. It is also contested if australopiths even exhibited heightened sexual dimorphism at all, which if correct would mean the range of variation is normal body size disparity between different individuals regardless of sex. It has also been argued that the femoral head

The femoral head (femur head or head of the femur) is the highest part of the thigh bone (femur). It is supported by the femoral neck.

Structure

The head is globular and forms rather more than a hemisphere, is directed upward, medialward, and a l ...

could be used for more accurate size modeling, and the femoral head size variation was the same for both sexes.

Lucy is one of the most complete Pliocene hominin skeletons, with over 40% preserved, but she was one of the smaller specimens of her species. Nonetheless, she has been the subject of several body mass estimates since her discovery, ranging from for absolute lower and upper bounds. Most studies report ranges within .

For the five makers of the Laetoli fossil trackways (S1, S2, G1, G2 and G3), based on the relationship between footprint length and bodily dimensions in modern humans, S1 was estimated to have been considerably large at about tall and in weight, S2 and , G1 and , G2 and , and G3 and . Based on these, S1 is interpreted to have been a male, and the rest females (G1 and G3 possibly juveniles), with ''A. afarensis'' being a highly dimorphic species.

Torso

DIK-1-1 preserves an ovalhyoid bone

The hyoid bone (lingual bone or tongue-bone) () is a horseshoe-shaped bone situated in the anterior midline of the neck between the chin and the thyroid cartilage. At rest, it lies between the base of the mandible and the third cervical vertebr ...

(which supports the tongue

The tongue is a muscular organ (anatomy), organ in the mouth of a typical tetrapod. It manipulates food for mastication and swallowing as part of the digestive system, digestive process, and is the primary organ of taste. The tongue's upper surfa ...

) more similar to those of chimpanzees and gorillas than the bar-shaped hyoid of humans and orangutans. This would suggest the presence of laryngeal air sac

Air sacs are spaces within an organism where there is the constant presence of air. Among modern animals, birds possess the most air sacs (9–11), with their extinct dinosaurian relatives showing a great increase in the pneumatization (presence ...

s characteristic of non-human African apes (and large gibbon

Gibbons () are apes in the family Hylobatidae (). The family historically contained one genus, but now is split into four extant genera and 20 species. Gibbons live in subtropical and tropical rainforest from eastern Bangladesh to Northeast India ...

s). Air sacs may lower the risk of hyperventilating when producing faster extended call sequences by rebreathing exhaled air from the air sacs. The loss of these in humans could have been a result of speech and resulting low risk of hyperventilating from normal vocalisation patterns.

It was previously thought that the australopithecines' spine was more like that of non-human apes than humans, with weak neck vertebra

In tetrapods, cervical vertebrae (singular: vertebra) are the vertebrae of the neck, immediately below the skull. Truncal vertebrae (divided into thoracic and lumbar vertebrae in mammals) lie caudal (toward the tail) of cervical vertebrae. In ...

e. However, the thickness of the neck vertebrae of KSD-VP-1/1 is similar to that of modern humans. Like humans, the series has a bulge and achieves maximum girth at C5 and 6, which in humans is associated with the brachial plexus

The brachial plexus is a network () of nerves formed by the anterior rami of the lower four cervical nerves and first thoracic nerve ( C5, C6, C7, C8, and T1). This plexus extends from the spinal cord, through the cervicoaxillary canal in th ...

, responsible for nerves and muscle innervation in the arms and hands. This could perhaps speak to advanced motor functions in the hands of ''A. afarensis'' and competency at precision tasks compared to non-human apes, possibly implicated in stone tool use or production. However, this could have been involved in head stability or posture rather than dexterity. A.L. 333-101 and A.L. 333-106 lack evidence of this feature. The neck vertebrae of KDS-VP-1/1 indicate that the nuchal ligament

The nuchal ligament is a ligament at the back of the neck that is continuous with the supraspinous ligament.

Structure

The nuchal ligament extends from the external occipital protuberance on the skull and median nuchal line to the spinous proces ...

, which stabilises the head while distance running in humans and other cursorial creatures, was either not well developed or absent. KSD-VP-1/1, preserving (among other skeletal elements) 6 rib fragments, indicates that ''A. afarensis'' had a bell-shaped ribcage

The rib cage, as an enclosure that comprises the ribs, vertebral column and sternum in the thorax of most vertebrates, protects vital organs such as the heart, lungs and great vessels.

The sternum, together known as the thoracic cage, is a semi- ...

instead of the barrel shaped ribcage exhibited in modern humans. Nonetheless, the constriction at the upper ribcage was not so marked as exhibited in non-human great apes and was quite similar to humans. Originally, the vertebral centra

The spinal column, a defining synapomorphy shared by nearly all vertebrates,Hagfish are believed to have secondarily lost their spinal column is a moderately flexible series of vertebrae (singular vertebra), each constituting a characteristic ...

preserved in Lucy were interpreted as being the T6, T8, T10, T11 and L3, but a 2015 study instead interpreted them as being T6, T7, T9, T10 and L3. DIK-1-1 shows that australopithecines had 12 thoracic vertebrae like modern humans instead of 13 like non-human apes. Like humans, australopiths likely had 5 lumbar vertebrae, and this series was likely long and flexible in contrast to the short and inflexible non-human great ape lumbar series.

Upper limbs

Like other australopiths, the ''A. afarensis'' skeleton exhibits a mosaic anatomy with some aspects similar to modern humans and others to non-human great apes. The pelvis and leg bones clearly indicate weight-bearing ability, equating to habitual bipedal, but the upper limbs are reminiscent of orangutans, which would indicate

Like other australopiths, the ''A. afarensis'' skeleton exhibits a mosaic anatomy with some aspects similar to modern humans and others to non-human great apes. The pelvis and leg bones clearly indicate weight-bearing ability, equating to habitual bipedal, but the upper limbs are reminiscent of orangutans, which would indicate arboreal

Arboreal locomotion is the Animal locomotion, locomotion of animals in trees. In habitats in which trees are present, animals have evolved to move in them. Some animals may scale trees only occasionally, but others are exclusively arboreal. Th ...

locomotion. However, this is much debated, as tree-climbing adaptations could simply be basal traits inherited from the great ape last common ancestor

In biology and genetic genealogy, the most recent common ancestor (MRCA), also known as the last common ancestor (LCA) or concestor, of a set of organisms is the most recent individual from which all the organisms of the set are descended. The ...

in the absence of major selective pressures at this stage to adopt a more humanlike arm anatomy.

The shoulder joint is somewhat in a shrugging position, closer to the head, like in non-human apes. Juvenile modern humans have a somewhat similar configuration, but this changes to the normal human condition with age; such a change does not appear to have occurred in ''A. afarensis'' development. It was once argued that this was simply a byproduct of being a small-bodied species, but the discovery of the similarly sized ''H. floresiensis

''Homo floresiensis'' also known as "Flores Man"; nicknamed "Hobbit") is an extinct species of small archaic human that inhabited the island of Flores, Indonesia, until the arrival of modern humans about 50,000 years ago.

The remains of an ...

'' with a more or less human shoulder configuration and larger ''A. afarensis'' specimens retaining the shrugging shoulders show this to not have been the case. The scapular spine

The spine of the scapula or scapular spine is a prominent plate of bone, which crosses obliquely the medial four-fifths of the scapula at its upper part, and separates the supra- from the infraspinatous fossa.

Structure

It begins at the vertical ...

(reflecting the strength of the back muscles) is closer to the range of gorillas.

The forearm of ''A. afarensis'' is incompletely known, yielding various brachial indexes (radial

Radial is a geometric term of location which may refer to:

Mathematics and Direction

* Vector (geometric), a line

* Radius, adjective form of

* Radial distance, a directional coordinate in a polar coordinate system

* Radial set

* A bearing f ...

length divided by humeral

The humerus (; ) is a long bone in the arm that runs from the shoulder to the elbow. It connects the scapula and the two bones of the lower arm, the radius and ulna, and consists of three sections. The humeral upper extremity consists of a rou ...

length) comparable to non-human great apes at the upper estimate and to modern humans at the lower estimate. The most complete ulna

The ulna (''pl''. ulnae or ulnas) is a long bone found in the forearm that stretches from the elbow to the smallest finger, and when in anatomical position, is found on the medial side of the forearm. That is, the ulna is on the same side of t ...

specimen, AL 438–1, is within the range of modern humans and other African apes. However, the L40-19 ulna is much longer, though well below that exhibited in orangutans and gibbons. The AL 438-1 metacarpals

In human anatomy, the metacarpal bones or metacarpus form the intermediate part of the skeleton, skeletal hand located between the phalanges of the fingers and the carpal bones of the wrist, which forms the connection to the forearm. The metacarpa ...

are proportionally similar to those of modern humans and orangutans. The ''A. afarensis'' hand is quite humanlike, though there are some aspects similar to orangutan hands which would have allowed stronger flexion of the fingers, and it probably could not handle large spherical or cylindrical objects very efficiently. Nonetheless, the hand seems to have been able to have produced a precision grip

A tactile pad is an area of skin that is particularly sensitive to pressure, temperature, or pain. Tactile pads are characterized by high concentrations of free nerve endings. In primates, the last Hand, phalanges in the fingers and toes have tact ...

necessary in using stone tool

A stone tool is, in the most general sense, any tool made either partially or entirely out of stone. Although stone tool-dependent societies and cultures still exist today, most stone tools are associated with prehistoric (particularly Stone Ag ...

s. However, it is unclear if the hand was capable of producing stone tools.

Lower limbs

The australopith pelvis is platypelloid and maintains a relatively wider distance between thehip socket

The acetabulum (), also called the cotyloid cavity, is a concave surface of the pelvis. The head of the femur meets with the pelvis at the acetabulum, forming the hip joint.

Structure

There are three bones of the ''os coxae'' (hip bone) that ...

s and a more oval shape. Despite being much smaller, Lucy's pelvic inlet

The pelvic inlet or superior aperture of the pelvis is a planar surface which defines the boundary between the pelvic cavity and the abdominal cavity (or, according to some authors, between two parts of the pelvic cavity, called lesser pelvis and ...

is wide, about the same breadth as that of a modern human woman. These were likely adaptations to minimise how far the centre of mass

In physics, the center of mass of a distribution of mass in space (sometimes referred to as the balance point) is the unique point where the weighted relative position of the distributed mass sums to zero. This is the point to which a force may ...

drops while walking upright in order to compensate for the short legs (rotating the hips may have been more important for ''A. afarensis''). Likewise, later ''Homo'' could reduce relative pelvic inlet size probably due to the elongation of the legs. Pelvic inlet size may not have been due to fetal head size (which would have increased birth canal

In mammals, the vagina is the elastic, muscular part of the female genital tract. In humans, it extends from the vestibule to the cervix. The outer vaginal opening is normally partly covered by a thin layer of mucosal tissue called the hymen. ...

and thus pelvic inlet width) as an ''A. afarensis'' newborn would have had a similar or smaller head size compared to that of a newborn chimpanzee. It is debated if the platypelloid pelvis provided poorer leverage for the hamstring

In human anatomy, a hamstring () is any one of the three posterior thigh muscles in between the hip and the knee (from medial to lateral: semimembranosus, semitendinosus and biceps femoris). The hamstrings are susceptible to injury.

In quadrupeds, ...

s or not.

The heel bone

In humans and many other primates, the calcaneus (; from the Latin ''calcaneus'' or ''calcaneum'', meaning heel) or heel bone is a bone of the tarsus of the foot which constitutes the heel. In some other animals, it is the point of the hock.

St ...

of ''A. afarensis'' adults and modern humans have the same adaptations for bipedality, indicating a developed grade of walking. The big toe is not dextrous as is in non-human apes (it is adducted), which would make walking more energy efficient at the expense of arboreal locomotion, no longer able to grasp onto tree branches with the feet. However, the foot of the infantile specimen DIK-1-1 indicates some mobility of the big toe, though not to the degree in non-human primates. This would have reduced walking efficiency, but a partially dextrous foot in the juvenile stage may have been important in climbing activities for food or safety, or made it easier for the infant to cling onto and be carried by an adult.

Palaeobiology

Diet and technology

''A. afarensis'' was likely ageneralist

A generalist is a person with a wide array of knowledge on a variety of subjects, useful or not. It may also refer to:

Occupations

* a physician who provides general health care, as opposed to a medical specialist; see also:

** General pract ...

omnivore

An omnivore () is an animal that has the ability to eat and survive on both plant and animal matter. Obtaining energy and nutrients from plant and animal matter, omnivores digest carbohydrates, protein, fat, and fiber, and metabolize the nutr ...

. Carbon isotope analysis on teeth from Hadar and Dikika 3.4–2.9 million years ago suggests a widely ranging diet between different specimens, with forest-dwelling specimens showing a preference for C3 forest plants, and bush- or grassland

A grassland is an area where the vegetation is dominated by grasses (Poaceae). However, sedge (Cyperaceae) and rush (Juncaceae) can also be found along with variable proportions of legumes, like clover, and other herbs. Grasslands occur natur ...

-dwelling specimens a preference for C4 CAM

Calmodulin (CaM) (an abbreviation for calcium-modulated protein) is a multifunctional intermediate calcium-binding messenger protein expressed in all eukaryotic cells. It is an intracellular target of the secondary messenger Ca2+, and the bin ...

savanna plants. C4 CAM sources include grass, seeds, roots, underground storage organ

A storage organ is a part of a plant specifically modified for storage of energy

(generally in the form of carbohydrates) or water. Storage organs often grow underground, where they are better protected from attack by herbivores. Plants that have ...

s, succulents

In botany, succulent plants, also known as succulents, are plants with parts that are thickened, fleshy, and engorged, usually to retain water in arid climates or soil conditions. The word ''succulent'' comes from the Latin word ''sucus'', meani ...

and perhaps creatures which ate those, such as termite

Termites are small insects that live in colonies and have distinct castes (eusocial) and feed on wood or other dead plant matter. Termites comprise the infraorder Isoptera, or alternatively the epifamily Termitoidae, within the order Blattode ...

s. Thus, ''A. afarensis'' appears to have been capable of exploiting a variety of food resources in a wide range of habitats. In contrast, the earlier ''A. anamensis'' and ''Ar. ramidus'', as well as modern savanna chimpanzees, target the same types of food as forest-dwelling counterparts despite living in an environment where these plants are much less abundant. Few modern primate species consume C4 CAM plants. The dental anatomy of ''A. afarensis'' is ideal for consuming hard, brittle foods, but microwearing patterns on the molars suggest that such foods were infrequently consumed, probably as fallback items in leaner times.

In 2009 at Dikika, Ethiopia, a rib fragment belonging to a cow-sized hoofed animal and a partial femur of a goat-sized juvenile bovid

The Bovidae comprise the biological family of cloven-hoofed, ruminant mammals that includes cattle, bison, buffalo, antelopes, and caprines. A member of this family is called a bovid. With 143 extant species and 300 known extinct species, the ...

was found to exhibit cut marks, and the former some crushing, which were initially interpreted as the oldest evidence of butchering with stone tools. If correct, this would make it the oldest evidence of sharp-edged stone tool use at 3.4 million years old, and would be attributable to ''A. afarensis'' as it is the only species known within the time and place. However, because the fossils were found in a sandstone

Sandstone is a clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate grains. Sandstones comprise about 20–25% of all sedimentary rocks.

Most sandstone is composed of quartz or feldspar (both silicates) ...

unit (and were modified by abrasive sand and gravel particles during the fossilisation process), the attribution to hominin activity is weak.

Society

It is highly difficult to speculate with accuracy the group dynamics of early hominins. ''A. afarensis'' is typically reconstructed with high levels of sexual dimorphism, with males much larger than females. Using general trends in modern primates, high sexual dimorphism usually equates to apolygynous

Polygyny (; from Neoclassical Greek πολυγυνία (); ) is the most common and accepted form of polygamy around the world, entailing the marriage of a man with several women.

Incidence

Polygyny is more widespread in Africa than in any ...

society due to intense male–male competition over females, like in the harem

Harem (Persian: حرمسرا ''haramsarā'', ar, حَرِيمٌ ''ḥarīm'', "a sacred inviolable place; harem; female members of the family") refers to domestic spaces that are reserved for the women of the house in a Muslim family. A hare ...

society of gorillas. However, it has also been argued that ''A. afarensis'' had much lower levels of dimorphism, and so had a multi-male kin-based society like chimpanzees. Low dimorphism could also be interpreted as having had a monogamous

Monogamy ( ) is a form of Dyad (sociology), dyadic Intimate relationship, relationship in which an individual has only one Significant other, partner during their lifetime. Alternately, only one partner at any one time (Monogamy#Serial monogamy, ...

society with strong male–male competition. Contrarily, the canine teeth are much smaller in ''A. afarensis'' than in non-human primates, which should indicate lower aggression because canine size is generally positively correlated with male–male aggression.

Birth

The platypelloid pelvis may have caused a different birthing mechanism from modern humans, with the

The platypelloid pelvis may have caused a different birthing mechanism from modern humans, with the neonate

An infant or baby is the very young offspring of human beings. ''Infant'' (from the Latin word ''infans'', meaning 'unable to speak' or 'speechless') is a formal or specialised synonym for the common term ''baby''. The terms may also be used to ...

entering the inlet facing laterally (the head was transversally orientated) until it exited through the pelvic outlet

The lower circumference of the lesser pelvis is very irregular; the space enclosed by it is named the inferior aperture or pelvic outlet. It is an important component of pelvimetry.

Boundaries

It has the following boundaries:

* anteriorly: the p ...

. This would be a non-rotational birth, as opposed to a fully rotational birth in humans. However, it has been suggested that the shoulders of the neonate may have been obstructed, and the neonate could have instead entered the inlet transversely and then rotated so that it exited through the outlet oblique to the main axis of the pelvis, which would be a semi-rotational birth. By this argument, there may not have been much space for the neonate to pass through the birth canal, causing a difficult childbirth

Childbirth, also known as labour and delivery, is the ending of pregnancy where one or more babies exits the internal environment of the mother via vaginal delivery or caesarean section. In 2019, there were about 140.11 million births globall ...

for the mother.

Gait

The Laetoli fossil trackway, generally attributed to ''A. afarensis'', indicates a rather developed grade of bipedal locomotion, more efficient than the bent-hip–bent-knee (BHBK) gait used by non-human great apes (though earlier interpretations of the gait include a BHBK posture or a shuffling movement). Trail A consists of short, broad prints resembling those of a two-and-a-half-year-old child, though it has been suggested this trail was made by the extinct bear '' Agriotherium africanus''. G1 is a trail consisting of four cycles likely made by a child. G2 and G3 are thought to have been made by two adults. In 2014, two more trackways were discovered made by one individual, named S1, extending for a total of . In 2015, a single footprint from a different individual, S2, was discovered. The shallowness of the toe prints would indicate a more flexed limb posture when the foot hit the ground and perhaps a less arched foot, meaning ''A. afarensis'' was less efficient at bipedal locomotion than humans. Some tracks feature a long drag mark probably left by the heel, which may indicate the foot was lifted at a low angle to the ground. For push-off, it appears weight shifted from the heel to the side of the foot and then the toes. Some footprints of S1 either indicate asymmetrical walking where weight was sometimes placed on the anterolateral part (the side of the front half of the foot) before toe-off, or sometimes the upper body was rotated mid-step. The angle of gait (the angle between the direction the foot is pointing in on touchdown and median line drawn through the entire trackway) ranges from 2–11° for both right and left sides. G1 generally shows wide and asymmetrical angles, whereas the others typically show low angles. The speed of the track makers has been variously estimated depending on the method used, with G1 reported at 0.47, 0.56, 0.64, 0.7 and 1 m/s (1.69, 2, 2.3, 2.5 and 3.6 km/h; 1.1, 1.3, 1.4, 1.6 and 2.2 mph); G2/3 reported at 0.37, 0.84 and 1 m/s (1.3, 2.9 and 3.6 km/h; 0.8, 1.8 and 2.2 mph); and S1 at . For comparison, modern humans typically walk at . The average step distance is , and stride distance . S1 appears to have had the highest average step and stride length of, respectively, and whereas G1–G3 averaged, respectively, 416, 453 and 433 mm (1.4, 1.5 and 1.4 ft) for step and 829, 880 and 876 mm (2.7, 2.9 and 2.9 ft) for stride.Pathology

Australopithecines, in general, seem to have had a high incidence rate of vertebral pathologies, possibly because their vertebrae were better adapted to withstand suspension loads in climbing than compressive loads while walking upright. Lucy presents marked thoracickyphosis

Kyphosis is an abnormally excessive convex curvature of the spine as it occurs in the thoracic and sacral regions. Abnormal inward concave ''lordotic'' curving of the cervical and lumbar regions of the spine is called lordosis. It can result fr ...

(hunchback) and was diagnosed with Scheuermann's disease

Scheuermann's disease is a Self-limiting (biology), self-limiting skeleton, skeletal disorder of childhood. Scheuermann's disease describes a condition where the vertebrae grow unevenly with respect to the sagittal plane; that is, the Posterior ( ...

, probably caused by overstraining her back, which can lead to a hunched posture in modern humans due to irregular curving of the spine. Because her condition presented quite similarly to that seen in modern human patients, this would indicate a basically human range of locomotor function in walking for ''A. afarensis''. The original straining may have occurred while climbing or swinging in the trees, though, even if correct, this does not indicate that her species was maladapted for arboreal behaviour, much like how humans are not maladapted for bipedal posture despite developing arthritis

Arthritis is a term often used to mean any disorder that affects joints. Symptoms generally include joint pain and stiffness. Other symptoms may include redness, warmth, swelling, and decreased range of motion of the affected joints. In som ...

. KSD-VP-1/1 seemingly exhibits compensatory action by the neck and lumbar vertebrae (gooseneck) consistent with thoracic kyphosis and Scheuermann's disease, but thoracic vertebrae are not preserved in this specimen.

In 2010, KSD-VP-1/1 presented evidence of a valgus deformity

A valgus deformity is a condition in which the bone segment distal

Standard anatomical terms of location are used to unambiguously describe the anatomy of animals, including humans. The terms, typically derived from Latin or Greek roots, des ...

of the left ankle involving the fibula

The fibula or calf bone is a leg bone on the lateral side of the tibia, to which it is connected above and below. It is the smaller of the two bones and, in proportion to its length, the most slender of all the long bones. Its upper extremity is ...

, with a bony ring developing on the fibula's joint surface extending the bone an additional . This was probably caused by a fibular fracture during childhood which improperly healed in a nonunion

Nonunion is permanent failure of healing following a broken bone unless intervention (such as surgery) is performed. A fracture with nonunion generally forms a structural resemblance to a fibrous joint, and is therefore often called a "false joi ...

.

In 2016, palaeoanthropologist John Kappelman argued that the fracturing exhibited by Lucy was consistent with a proximal humerus fracture, which is most often caused by falling in humans. He then concluded she died from falling out of a tree, and that ''A. afarensis'' slept in trees or climbed trees to escape predators. However, similar fracturing is exhibited in many other creatures in the area, including the bones of antelope

The term antelope is used to refer to many species of even-toed ruminant that are indigenous to various regions in Africa and Eurasia.

Antelope comprise a wastebasket taxon defined as any of numerous Old World grazing and browsing hoofed mammals ...

, elephant

Elephants are the largest existing land animals. Three living species are currently recognised: the African bush elephant, the African forest elephant, and the Asian elephant. They are the only surviving members of the family Elephantidae an ...

s, giraffe

The giraffe is a large African hoofed mammal belonging to the genus ''Giraffa''. It is the tallest living terrestrial animal and the largest ruminant on Earth. Traditionally, giraffes were thought to be one species, ''Giraffa camelopardalis ...

s and rhino

A rhinoceros (; ; ), commonly abbreviated to rhino, is a member of any of the five extant species (or numerous extinct species) of odd-toed ungulates in the family Rhinocerotidae. (It can also refer to a member of any of the extinct species o ...

s, and may well simply be taphonomic bias (fracturing was caused by fossilisation). Lucy may also have been killed in an animal attack or a mudslide

A mudflow or mud flow is a form of mass wasting involving fast-moving flow of debris that has become liquified by the addition of water. Such flows can move at speeds ranging from 3 meters/minute to 5 meters/second. Mudflows contain a significa ...

.

The 13 AL 333 individuals are thought to have been deposited at about the same time as one another, bear little evidence of carnivore activity, and were buried on a stretch of a hill. In 1981, anthropologists James Louis Aronson and Taieb suggested they were killed in a flash flood

A flash flood is a rapid flooding of low-lying areas: washes, rivers, dry lakes and depressions. It may be caused by heavy rain associated with a severe thunderstorm, hurricane, or tropical storm, or by meltwater from ice or snow flowing o ...

. British archaeologist Paul Pettitt

Paul Barry Pettitt, FSA is a British archaeologist and academic. He specialises in the Palaeolithic era, with particular focus on claims of art and burial practices of the Neanderthals and Pleistocene ''Homo sapiens'', and methods of determinin ...

considered natural causes unlikely and, in 2013, speculated that these individuals were purposefully hidden in tall grass by other hominins (funerary caching). This behaviour has been documented in modern primates, and may be done so that the recently deceased do not attract predators to living grounds.

Palaeoecology

''A. afarensis'' does not appear to have had a preferred environment, and inhabited a wide range of habitats such as open grasslands or woodlands, shrublands, and lake- or riverside forests. Likewise, the animal assemblage varied widely from site to site. The Pliocene of East Africa was warm and wet compared to the precedingMiocene

The Miocene ( ) is the first geological epoch of the Neogene Period and extends from about (Ma). The Miocene was named by Scottish geologist Charles Lyell; the name comes from the Greek words (', "less") and (', "new") and means "less recen ...

, with the dry season

The dry season is a yearly period of low rainfall, especially in the tropics. The weather in the tropics is dominated by the tropical rain belt, which moves from the northern to the southern tropics and back over the course of the year. The te ...

lasting about four months based on floral, faunal and geological evidence. The extended rainy season

The rainy season is the time of year when most of a region's average annual rainfall occurs.

Rainy Season may also refer to:

* ''Rainy Season'' (short story), a 1989 short horror story by Stephen King

* "Rainy Season", a 2018 song by Monni

* ''T ...

would have made more desirable foods available to hominins for most of the year. Africa 4–3 million years ago featured a greater diversity of large carnivores than today, and australopithecines likely fell prey to these dangerous creatures, including hyena

Hyenas, or hyaenas (from Ancient Greek , ), are feliform carnivoran mammals of the family Hyaenidae . With only four extant species (each in its own genus), it is the fifth-smallest family in the Carnivora and one of the smallest in the clas ...

s, ''Panthera

''Panthera'' is a genus within the family (biology), family Felidae that was named and described by Lorenz Oken in 1816 who placed all the spotted cats in this group. Reginald Innes Pocock revised the classification of this genus in 1916 as co ...

'', cheetah

The cheetah (''Acinonyx jubatus'') is a large cat native to Africa and central Iran. It is the fastest land animal, estimated to be capable of running at with the fastest reliably recorded speeds being , and as such has evolved specialized ...

s, and the sabre-toothed ''Megantereon

''Megantereon'' was a genus of prehistoric machairodontine saber-toothed cat that lived in North America, Eurasia, and Africa. It may have been the ancestor of ''Smilodon''.

Taxonomy

Fossil fragments have been found in Africa, Eurasia, and No ...

'', ''Dinofelis

''Dinofelis'' is a genus of extinct sabre-toothed cats belonging to the tribe Metailurini or possibly Smilodontini. They were widespread in Europe, Asia, Africa and North America at least 5 million to about 1.2 million years ago (Early Pliocene t ...

'', ''Homotherium

''Homotherium'', also known as the scimitar-toothed cat or scimitar cat, is an extinct genus of machairodontine saber-toothed predator, often termed scimitar-toothed cats, that inhabited North America, South America, Eurasia, and Africa during th ...

'' and ''Machairodus

''Machairodus'' (from el, μαχαίρα , 'knife' and el, ὀδούς 'tooth') is a genus of large machairodontine saber-toothed cats that lived in Africa, Eurasia and North America during the late Miocene. It is the animal from which the su ...

''.

Australopithecines and early ''Homo'' likely preferred cooler conditions than later ''Homo'', as there are no australopithecine sites that were below in elevation at the time of deposition. This would mean that, like chimpanzees, they often inhabited areas with an average diurnal temperature of , dropping to at night. At Hadar, the average temperature from 3.4 to 2.95 million years ago was about .

See also

* ''Ardipithecus ramidus

''Ardipithecus ramidus'' is a species of australopithecine from the Afar region of Early Pliocene Ethiopia 4.4 million years ago (mya). ''A. ramidus'', unlike modern hominids, has adaptations for both walking on two legs ( bipedality) and life i ...

''

* ''Australopithecus anamensis

''Australopithecus anamensis'' is a hominin species that lived approximately between 4.2 and 3.8 million years ago and is the oldest known ''Australopithecus'' species, living during the Plio-Pleistocene era.

Nearly one hundred fossil specimens ...

''

* ''Australopithecus bahrelghazali

''Australopithecus bahrelghazali'' is an extinct species of australopithecine discovered in 1995 at Koro Toro, Bahr el Gazel, Chad, existing around 3.5 million years ago in the Pliocene. It is the first and only australopithecine known from Ce ...

''

* '' Australopithecus deyiremeda''

* ''Kenyanthropus

''Kenyanthropus'' is a hominin genus identified from the Lomekwi site by Lake Turkana, Kenya, dated to 3.3 to 3.2 million years ago during the Middle Pliocene. It contains one species, ''K. platyops'', but may also include the 2 million year ...

''

* LD 350-1

LD 350-1 is the earliest known specimen of the genus ''Homo'', dating to 2.8–2.75 million years ago (mya), found in the Ledi-Geraru site in the Afar Region of Ethiopia. The specimen was discovered in silts above the Gurumaha Tuff section of the ...

* List of fossil sites

This list of fossil sites is a worldwide list of localities known well for the presence of fossils. Some entries in this list are notable for a single, unique find, while others are notable for the large number of fossils found there. Many of t ...

(with link directory)

* List of human evolution fossils

The following tables give an overview of notable finds of Hominini, hominin fossils and Skeleton, remains relating to human evolution, beginning with the formation of the tribe Hominini (the divergence of the Chimpanzee–human last common ancest ...

(with images)

* Lomekwi

Lomekwi 3 is the name of an archaeological site in Kenya where ancient stone tools have been discovered dating to 3.3 million years ago, which make them the oldest ever found.

Discovery

In July 2011, a team of archeologists led by Sonia Harman ...

References

72. Bonnefille, R. ; Potts, R.; Chalie, F.; Jolly, D. (2004). "High-Resolution Vegetation and Climate Change Associated with Pliocene Australopithecus afarensis". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 101 (33): 12125–12129. Bibcode:2004PNAS..10112125B. doi:10.1073/pnas.0401709101. PMC 514445. PMID 15304655.Further reading

* * * *External links

Becoming Human: Paleoanthropology, Evolution and Human Origins

The Smithsonian's Human Origins Program

Human Timeline (Interactive)

– Smithsonian {{Authority control afarensis Pliocene primates Mammals described in 1978 Fossil taxa described in 1978 Prehistoric Ethiopia Prehistoric Kenya Pliocene mammals of Africa Tool-using mammals Taxa named by Donald Johanson Taxa named by Tim D. White Archaeology of Eastern Africa