2001 anthrax attacks on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The 2001 anthrax attacks, also known as Amerithrax (a portmanteau of "America" and " anthrax", from its FBI case name), occurred in the United States over the course of several weeks beginning on September 18, 2001, one week after the September 11 terrorist attacks. Letters containing anthrax spores were mailed to several news media offices and to

The ''New York Post'' and NBC News letters contained the following note:

The ''New York Post'' and NBC News letters contained the following note:

09-11-01

THIS IS NEXT

TAKE PENACILIN NOW

DEATH TO AMERICA

DEATH TO ISRAEL

ALLAH IS GREAT

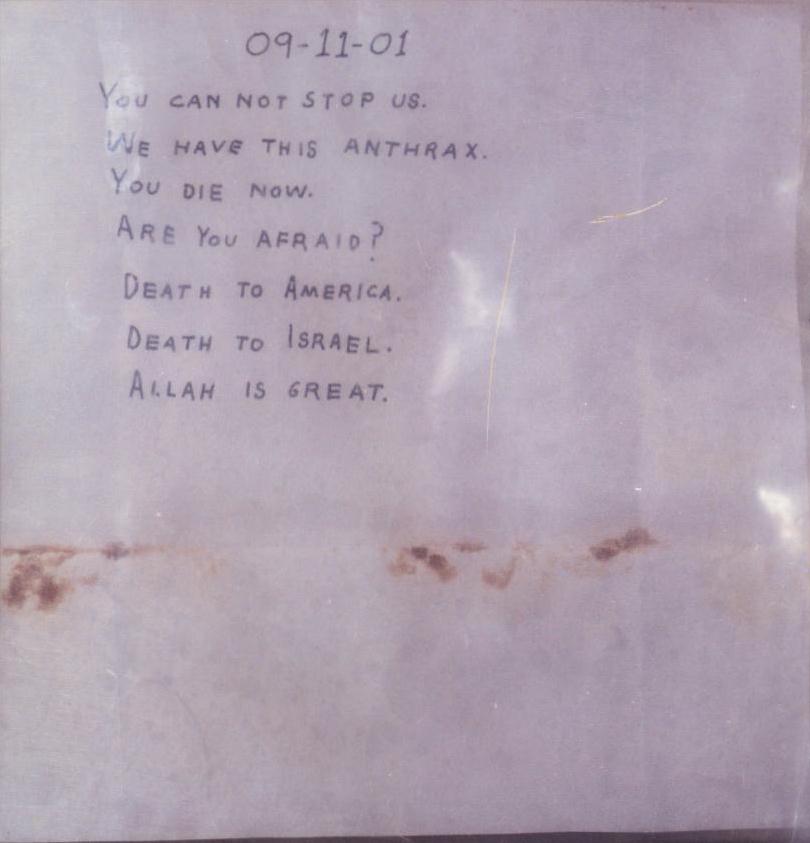

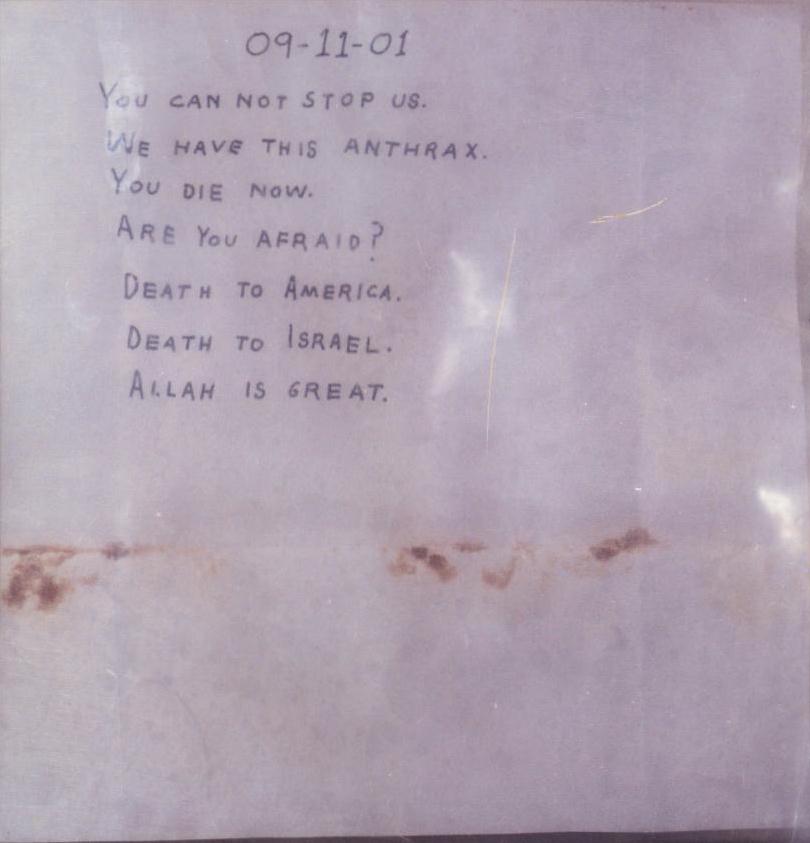

The second note was addressed to Senators Daschle and Leahy and read:

The second note was addressed to Senators Daschle and Leahy and read:

09-11-01

YOU CAN NOT STOP US.

WE HAVE THIS ANTHRAX.

YOU DIE NOW.

ARE YOU AFRAID?

DEATH TO AMERICA.

DEATH TO ISRAEL.

ALLAH IS GREAT.

All of the letters were copies made by a copy machine, and the originals were never found. Each letter was trimmed to a slightly different size. The Senate letter uses punctuation, while the media letter does not. The handwriting on the media letter and envelopes is roughly twice the size of the handwriting on the Senate letter and envelopes. The envelopes addressed to Senators Daschle and Leahy had a fictitious return address:

4th Grade

Greendale School

Franklin Park NJ 08852

Democratic

Democrat, Democrats, or Democratic may refer to:

Politics

*A proponent of democracy, or democratic government; a form of government involving rule by the people.

*A member of a Democratic Party:

**Democratic Party (United States) (D)

**Democratic ...

Senators Tom Daschle

Thomas Andrew Daschle ( ; born December 9, 1947) is an American politician and lobbyist who served as a United States senator from South Dakota from 1987 to 2005. A member of the Democratic Party, he became U.S. Senate Minority Leader in 1995 an ...

and Patrick Leahy

Patrick Joseph Leahy (; born March 31, 1940) is an American politician and attorney who is the senior United States senator from Vermont and serves as the president pro tempore of the United States Senate. A member of the Democratic Party, L ...

, killing five people and infecting 17 others. According to the FBI, the ensuing investigation became "one of the largest and most complex in the history of law enforcement".

A major focus in the early years of the investigation was bioweapons expert Steven Hatfill

Steven Jay Hatfill (born October 24, 1953) is an American physician, pathologist and biological weapons expert. He became the subject of extensive media coverage beginning in mid-2002, when he was a suspect in the 2001 anthrax attacks.Lichtblau, ...

, who was eventually exonerated. Bruce Edwards Ivins, a scientist at the government's biodefense labs at Fort Detrick

Fort Detrick () is a United States Army Futures Command installation located in Frederick, Maryland. Historically, Fort Detrick was the center of the U.S. biological weapons program from 1943 to 1969. Since the discontinuation of that program, i ...

in Frederick, Maryland

Frederick is a city in and the county seat of Frederick County, Maryland. It is part of the Baltimore–Washington metropolitan area, Baltimore–Washington Metropolitan Area. Frederick has long been an important crossroads, located at the inter ...

, became a focus around April 4, 2005. On April 11, 2007, Ivins was put under periodic surveillance and an FBI document stated that he was "an extremely sensitive suspect in the 2001 anthrax attacks". On July 29, 2008, Ivins committed suicide with an overdose of acetaminophen (Tylenol).

Federal prosecutors declared Ivins the sole perpetrator on August 6, 2008, based on DNA evidence leading to an anthrax vial in his lab. Two days later, Senator Chuck Grassley

Charles Ernest Grassley (born September 17, 1933) is an American politician serving as the president pro tempore emeritus of the United States Senate, and the senior United States senator from Iowa, having held the seat since 1981. In 2022, ...

and Representative Rush D. Holt, Jr. called for hearings into the Department of Justice and FBI's handling of the investigation. The FBI formally closed its investigation on February 19, 2010.

In 2008, the FBI requested a review of the scientific methods used in their investigation from the National Academy of Sciences, which released their findings in the 2011 report ''Review of the Scientific Approaches Used During the FBI's Investigation of the 2001 Anthrax Letters''. The report cast doubt on the government's conclusion that Ivins was the perpetrator, finding that the type of anthrax used in the letters was correctly identified as the Ames strain of the bacterium, but that there was insufficient scientific evidence for the FBI's assertion that it originated from Ivins's laboratory. The FBI responded by pointing out that the review panel asserted that it would not be possible to reach a definite conclusion based on science alone, and said that a combination of factors led the FBI to conclude that Ivins had been the perpetrator. Some information is still sealed concerning the case and Ivins's mental health. The government settled lawsuits that were filed by the widow of the first anthrax victim Bob Stevens for $2.5 million with no admission of liability. The settlement was reached solely for the purpose of "avoiding the expenses and risks of further litigations", according to a statement in the agreement.

Context

The anthrax attacks began just a week after theSeptember 11 attacks

The September 11 attacks, commonly known as 9/11, were four coordinated suicide terrorist attacks carried out by al-Qaeda against the United States on Tuesday, September 11, 2001. That morning, nineteen terrorists hijacked four commerc ...

, which had caused the destruction of the World Trade Center in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the U ...

, damage to The Pentagon

The Pentagon is the headquarters building of the United States Department of Defense. It was constructed on an accelerated schedule during World War II. As a symbol of the U.S. military, the phrase ''The Pentagon'' is often used as a metonym ...

in Arlington, Virginia

Arlington County is a county in the Commonwealth of Virginia. The county is situated in Northern Virginia on the southwestern bank of the Potomac River directly across from the District of Columbia, of which it was once a part. The county i ...

, and the crash of an airliner in Shanksville, Pennsylvania. The attacks came in two waves. The first set of letters containing anthrax had a Trenton, New Jersey

Trenton is the capital city, capital city (New Jersey), city of the U.S. state of New Jersey and the county seat of Mercer County, New Jersey, Mercer County. It was the capital of the United States from November 1 to December 24, 1784.

, postmark

A postmark is a postal marking made on an envelope, parcel, postcard or the like, indicating the place, date and time that the item was delivered into the care of a postal service, or sometimes indicating where and when received or in transit. ...

dated September 18, 2001. Five letters are believed to have been mailed at this time to ABC News

ABC News is the journalism, news division of the American broadcast network American Broadcasting Company, ABC. Its flagship program is the daily evening newscast ''ABC World News Tonight, ABC World News Tonight with David Muir''; other progra ...

, CBS News, NBC News

NBC News is the news division of the American broadcast television network NBC. The division operates under NBCUniversal Television and Streaming, a division of NBCUniversal, which is, in turn, a subsidiary of Comcast. The news division's ...

and the ''New York Post

The ''New York Post'' (''NY Post'') is a conservative daily tabloid newspaper published in New York City. The ''Post'' also operates NYPost.com, the celebrity gossip site PageSix.com, and the entertainment site Decider.com.

It was established ...

'', all located in New York City, and to the '' National Enquirer'' at American Media, Inc. (AMI) in Boca Raton, Florida

Boca Raton ( ; es, Boca Ratón, link=no, ) is a city in Palm Beach County, Florida, United States. It was first incorporated on August 2, 1924, as "Bocaratone," and then incorporated as "Boca Raton" in 1925. The population was 97,422 in the ...

.

The first known victim of the attacks, Robert Stevens, who worked at the '' Sun'' tabloid, also published by AMI, died on October 5, 2001, four days after entering a Florida hospital with an undiagnosed illness that caused him to vomit and be short of breath. The presumed letter that contained the anthrax that killed Stevens was never found. Only the ''New York Post

The ''New York Post'' (''NY Post'') is a conservative daily tabloid newspaper published in New York City. The ''Post'' also operates NYPost.com, the celebrity gossip site PageSix.com, and the entertainment site Decider.com.

It was established ...

'' and NBC News

NBC News is the news division of the American broadcast television network NBC. The division operates under NBCUniversal Television and Streaming, a division of NBCUniversal, which is, in turn, a subsidiary of Comcast. The news division's ...

letters were actually identified; the existence of the other three letters is inferred because individuals at ABC, CBS and AMI became infected with anthrax. Scientists examining the anthrax from the ''New York Post'' letter said it was a clumped coarse brown granular material which looked similar to dog food.

Two more anthrax letters, bearing the same Trenton postmark, were dated October 9, three weeks after the first mailing. The letters were addressed to two U.S. Senators, Tom Daschle

Thomas Andrew Daschle ( ; born December 9, 1947) is an American politician and lobbyist who served as a United States senator from South Dakota from 1987 to 2005. A member of the Democratic Party, he became U.S. Senate Minority Leader in 1995 an ...

of South Dakota and Patrick Leahy

Patrick Joseph Leahy (; born March 31, 1940) is an American politician and attorney who is the senior United States senator from Vermont and serves as the president pro tempore of the United States Senate. A member of the Democratic Party, L ...

of Vermont. At the time, Daschle was the Senate majority leader and Leahy was head of the Senate Judiciary Committee; both were members of the Democratic Party. The Daschle letter was opened by an aide, Grant Leslie, on October 15, after which the government mail service was immediately shut down. The unopened Leahy letter was discovered in an impounded mailbag on November 16. The Leahy letter had been misdirected to the State Department mail annex in Sterling, Virginia

Sterling, Virginia, refers most specifically to a census-designated place (CDP) in Loudoun County, Virginia, United States. The population of the CDP as of the 2010 United States Census was 27,822. The CDP boundaries are confined to a relatively ...

, because a ZIP code was misread; a postal worker there, David Hose, contracted inhalational anthrax.

More potent than the first anthrax letters, the material in the Senate letters was a highly refined dry powder consisting of about one gram of nearly pure spores. A series of conflicting news reports appeared, some claiming the powders had been "weaponized" with silica

Silicon dioxide, also known as silica, is an oxide of silicon with the chemical formula , most commonly found in nature as quartz and in various living organisms. In many parts of the world, silica is the major constituent of sand. Silica is o ...

. Bioweapons experts who later viewed images of the anthrax used in the attacks saw no indication of "weaponization". Tests at Sandia National Laboratories

Sandia National Laboratories (SNL), also known as Sandia, is one of three research and development laboratories of the United States Department of Energy's National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA). Headquartered in Kirtland Air Force Bas ...

in early 2002 confirmed that the attack powders were not weaponized.

At least 22 people developed anthrax infections, 11 of whom contracted the especially life-threatening inhalational variety. Five died of inhalational anthrax: Stevens; two employees of the Brentwood mail facility in Washington, D.C. (Thomas Morris Jr. and Joseph Curseen), and two whose source of exposure to the bacteria is still unknown: Kathy Nguyen, a Vietnamese immigrant resident of the New York City borough of the Bronx

The Bronx () is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Bronx County, in the state of New York. It is south of Westchester County; north and east of the New York City borough of Manhattan, across the Harlem River; and north of the New ...

who worked in the city, and the last known victim, Ottilie Lundgren, a 94-year-old widow of a prominent judge from Oxford, Connecticut.

Because it took so long to identify a culprit, the 2001 anthrax attacks have been compared to the Unabomber attacks which took place from 1978 to 1995.

The letters

Authorities believe that the anthrax letters were mailed fromPrinceton, New Jersey

Princeton is a municipality with a borough form of government in Mercer County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey. It was established on January 1, 2013, through the consolidation of the Borough of Princeton and Princeton Township, both of whi ...

. Investigators found anthrax spores in a city street mailbox located at 10 Nassau Street near the Princeton University

Princeton University is a private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the n ...

campus. About 600 mailboxes were tested for anthrax which could have been used to mail the letters, and the Nassau Street box was the only one to test positive.

The ''New York Post'' and NBC News letters contained the following note:

The ''New York Post'' and NBC News letters contained the following note:

The second note was addressed to Senators Daschle and Leahy and read:

The second note was addressed to Senators Daschle and Leahy and read:

Franklin Park, New Jersey

Franklin Park is an unincorporated community and census-designated place (CDP) located within Franklin Township, in Somerset County, New Jersey, United States.Monmouth Junction, New Jersey

Monmouth Junction is an unincorporated community and census designated place (CDP) located within South Brunswick Township, in Middlesex County, New Jersey, Middlesex County, New Jersey, United States.South Brunswick Township, New Jersey.

The letters sent to the media contained a coarse brown material, while the letters sent to the two U.S. Senators contained a fine powder. The brown granular anthrax mostly caused cutaneous anthrax infections (9 out of 12 cases), although Kathy Nguyen's case of

The letters sent to the media contained a coarse brown material, while the letters sent to the two U.S. Senators contained a fine powder. The brown granular anthrax mostly caused cutaneous anthrax infections (9 out of 12 cases), although Kathy Nguyen's case of

flask RMR-1029

was the parent material of the anthrax spore powder. Ivins had sole control over that flask.

Authorities traveled to six continents, interviewed over 9,000 people, conducted 67 searches and issued over 6,000 subpoenas. "Hundreds of FBI personnel worked the case at the outset, struggling to discern whether the Sept. 11 al-Qaeda attacks and the anthrax murders were connected before eventually concluding that they were not." In September 2006, there were still 17 FBI agents and 10 postal inspectors assigned to the case, including FBI Special Agent

Authorities traveled to six continents, interviewed over 9,000 people, conducted 67 searches and issued over 6,000 subpoenas. "Hundreds of FBI personnel worked the case at the outset, struggling to discern whether the Sept. 11 al-Qaeda attacks and the anthrax murders were connected before eventually concluding that they were not." In September 2006, there were still 17 FBI agents and 10 postal inspectors assigned to the case, including FBI Special Agent

", David Rose and Ed Vulliamy, ''

False leads

The Amerithrax investigation involved many leads which took time to evaluate and resolve. Among them were numerous letters which initially appeared to be related to the anthrax attacks but were never directly linked. For example, before the New York letters were found,hoax

A hoax is a widely publicized falsehood so fashioned as to invite reflexive, unthinking acceptance by the greatest number of people of the most varied social identities and of the highest possible social pretensions to gull its victims into pu ...

letters mailed from St. Petersburg, Florida, were thought to be the anthrax letters or related to them. A letter received at the Microsoft offices in Reno, Nevada

Reno ( ) is a city in the northwest section of the U.S. state of Nevada, along the Nevada-California border, about north from Lake Tahoe, known as "The Biggest Little City in the World". Known for its casino and tourism industry, Reno is the c ...

, after the discovery of the Daschle letters, gave a false positive

A false positive is an error in binary classification in which a test result incorrectly indicates the presence of a condition (such as a disease when the disease is not present), while a false negative is the opposite error, where the test resul ...

in a test for anthrax. Later, because the letter had been sent from Malaysia, Marilyn Thompson of ''The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'' (also known as the ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'') is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C. It is the most widely circulated newspaper within the Washington metropolitan area and has a large n ...

'' connected the letter to Steven Hatfill

Steven Jay Hatfill (born October 24, 1953) is an American physician, pathologist and biological weapons expert. He became the subject of extensive media coverage beginning in mid-2002, when he was a suspect in the 2001 anthrax attacks.Lichtblau, ...

, whose girlfriend was from Malaysia. The letter merely contained a check and some pornography, and was neither a threat nor a hoax.

A copycat

Copycat refers to a person who copies some aspect of some thing or somebody else.

Copycat may also refer to:

Intellectual property rights

* Copyright infringement, use of another’s ideas or words without permission

* Patent infringement, a ...

hoax letter containing harmless white powder was opened by reporter Judith Miller in ''The New York Times'' newsroom.

Also unconnected to the anthrax attacks was a large envelope received at American Media, Inc., in Boca Raton, Florida (which was among the victims of the attacks) in September 2001. It was addressed "Please forward to Jennifer Lopez c/o The Sun", containing a metal cigar tube with a cheap cigar inside, an empty can of chewing tobacco, a small detergent carton, pink powder, a Star of David pendant, and "a handwritten letter to Jennifer Lopez. The writer said how much he loved her and asked her to marry him." Another letter, which mimicked the original anthrax letter to Senator Daschle, was mailed to Daschle from London in November 2001, at a time when Hatfill was in England, not far from London. Shortly before the discovery of the anthrax letters, someone sent a letter to authorities stating, " Dr. Assaad is a potential biological terrorist." No connection to the anthrax letters was ever found.

During the first years of the FBI's investigation, Don Foster, a professor of English at Vassar College, attempted to connect the anthrax letters and various hoax letters from the same period to Steven Hatfill. Foster's beliefs were published in '' Vanity Fair'' and ''Reader's Digest

''Reader's Digest'' is an American general-interest family magazine, published ten times a year. Formerly based in Chappaqua, New York, it is now headquartered in midtown Manhattan. The magazine was founded in 1922 by DeWitt Wallace and his w ...

''. Hatfill sued and was later exonerated. The lawsuit was settled out of court.

Anthrax material

The letters sent to the media contained a coarse brown material, while the letters sent to the two U.S. Senators contained a fine powder. The brown granular anthrax mostly caused cutaneous anthrax infections (9 out of 12 cases), although Kathy Nguyen's case of

The letters sent to the media contained a coarse brown material, while the letters sent to the two U.S. Senators contained a fine powder. The brown granular anthrax mostly caused cutaneous anthrax infections (9 out of 12 cases), although Kathy Nguyen's case of inhalational anthrax

Anthrax is an infection caused by the bacterium ''Bacillus anthracis''. It can occur in four forms: skin, lungs, intestinal, and injection. Symptom onset occurs between one day and more than two months after the infection is contracted. The sk ...

occurred at the same time and in the same general area as two cutaneous cases and several other exposures. The AMI letter which caused inhalation cases in Florida appears to have been mailed at the same time as the other media letters. The fine powder anthrax sent to Daschle and Leahy mostly caused the more dangerous form of infection known as inhalational anthrax (8 out of 10 cases). Postal worker Patrick O'Donnell and accountant Linda Burch contracted cutaneous anthrax

Anthrax is an infection caused by the bacterium ''Bacillus anthracis''. It can occur in four forms: skin, lungs, intestinal, and injection. Symptom onset occurs between one day and more than two months after the infection is contracted. The sk ...

from the Senate letters.

All of the material was derived from the same bacterial strain known as the Ames strain. The Ames strain is a common strain isolated from a cow in Texas in 1981. The name "Ames" refers to the town of Ames, Iowa

Ames () is a city in Story County, Iowa, United States, located approximately north of Des Moines in central Iowa. It is best known as the home of Iowa State University (ISU), with leading agriculture, design, engineering, and veterinary med ...

, but was mistakenly attached to this isolate in 1981 because of a mix-up about the mailing label on a package. First researched at the United States Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID), at Fort Detrick, Maryland, the Ames strain was subsequently distributed to sixteen bio-research labs within the U.S., as well as three international locations (Canada, Sweden and the United Kingdom).

DNA sequencing of the anthrax collected from Robert Stevens (the first victim) was conducted at The Institute for Genomic Research (TIGR) beginning in December 2001. Sequencing was finished within a month and the analysis was published in the journal ''Science'' in early 2002.

Radiocarbon dating

Radiocarbon dating (also referred to as carbon dating or carbon-14 dating) is a method for determining the age of an object containing organic material by using the properties of radiocarbon, a radioactive isotope of carbon.

The method was de ...

conducted by the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) is a federal research facility in Livermore, California, United States. The lab was originally established as the University of California Radiation Laboratory, Livermore Branch in 1952 in response ...

in June 2002 established that the anthrax was cultured

Culture () is an umbrella term which encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, customs, capabilities, and habits of the individuals in these groups.Tylor ...

no more than two years before the mailings.

Mutations

Early in 2002, it was noted that there were variants or mutations in the anthrax cultures that were grown from powder found in the letters. Scientists at TIGR sequenced the complete genomes from many of these isolates during the period from 2002 to 2004. This sequencing identified three relatively large changes in some of the isolates, each comprising a region of DNA that had been duplicated or triplicated. The size of these regions ranged from 823 to 2607 base pairs, and all occurred near the same genes. Details of these mutations were published in 2011 in the ''Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

''Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America'' (often abbreviated ''PNAS'' or ''PNAS USA'') is a peer-reviewed multidisciplinary scientific journal. It is the official journal of the National Academy of Sc ...

''. These changes became the basis of PCR PCR or pcr may refer to:

Science

* Phosphocreatine, a phosphorylated creatine molecule

* Principal component regression, a statistical technique

Medicine

* Polymerase chain reaction

** COVID-19 testing, often performed using the polymerase chain r ...

assays used to test other samples to find any that contained the same mutations. The assays were validated over the many years of the investigation, and a repository of Ames samples was also built. From roughly 2003 to 2006 the repository and the screening of the 1,070 Ames samples in that repository were completed.

Based on the testing, the FBI concluded thaflask RMR-1029

was the parent material of the anthrax spore powder. Ivins had sole control over that flask.

Controversy over coatings and additives

On October 24, 2001, USAMRIID scientist Peter Jahrling was summoned to the White House after he reported signs that silicon had been added to the anthrax recovered from the letter addressed to Daschle. Silicon would make the anthrax more capable of penetrating the lungs. Seven years later, Jahrling told the ''Los Angeles Times'' on September 17, 2008, "I believe I made an honest mistake", adding that he had been "overly impressed" by what he thought he saw under the microscope. Richard Preston's book provides details of conversations and events at USAMRIID during the period from October 16, 2001, to October 25, 2001. Key scientists described to Preston what they were thinking during that period. When the Daschle spores first arrived at USAMRIID, the key concern was thatsmallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) ce ...

viruses might be mixed with the spores. "Jahrling met ohnEzzell in a hallway and said, in a loud voice, 'Goddamn it, John, we need to know if the powder is laced with smallpox.'" Thus, the initial search was for signs of smallpox viruses. On October 16, USAMRIID scientists began by examining spores that had been "in a milky white liquid" from "a field test done by the FBI's Hazardous Materials Response Unit". Liquid chemicals were then used to deactivate the spores. When scientists turned up the power on the electron beam of the Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM), "The spores began to ooze." According to Preston,

:"Whoa," Jahrling muttered, hunched over the eyepieces. Something was boiling off the spores. "This is clearly bad stuff," he said. This was not your mother's anthrax. The spores had something in them, an additive, perhaps. Could this material have come from a national bioweapons program? From Iraq? Did al-Qaeda have anthrax capability that was this good?On October 25, 2001, the day after senior officials at the White House were informed that "additives" had been found in the anthrax, USAMRIID scientist Tom Geisbert took a different, irradiated sample of the Daschle anthrax to the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology (AFIP) to "find out if the powder contained any metals or elements". AFIP's energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometer reportedly indicated "that there were two extra elements in the spores: silicon and oxygen. Silicon dioxide is glass. The anthrax terrorist or terrorists had put powdered glass, or silica, into the anthrax. The silica was powdered so finely that under Geisbert's electron microscope it had looked like fried-egg gunk dripping off the spores." The "goop" Peter Jahrling had seen oozing from the spores was not seen when AFIP examined different spores killed with radiation. The controversy began the day after the White House meeting. ''The New York Times'' reported, "Contradicting Some U.S. Officials, 3 Scientists Call Anthrax Powder High-Grade – Two Experts say the anthrax was altered to produce a more deadly weapon", and ''The Washington Post'' reported, "Additive Made Spores Deadlier". Countless news stories discussed the "additives" for the next eight years, continuing into 2010. Later, the FBI claimed a "lone individual" could have created the anthrax spores for as little as $2,500, using readily available laboratory equipment. A number of press reports appeared suggesting the Senate anthrax had coatings and additives. ''

Newsweek

''Newsweek'' is an American weekly online news magazine co-owned 50 percent each by Dev Pragad, its president and CEO, and Johnathan Davis, who has no operational role at ''Newsweek''. Founded as a weekly print magazine in 1933, it was widely ...

'' reported the anthrax sent to Senator Leahy had been coated with a chemical compound previously unknown to bioweapons experts. On October 28, 2002, ''The Washington Post'' reported "FBI's Theory on Anthrax is Doubted", suggesting that the senate spores were coated with fumed silica. Two bioweapons experts that were utilized as consultants by the FBI, Kenneth Alibek

Kanatzhan "Kanat" Alibekov ( kk, Қанатжан Байзақұлы Әлібеков, Qanatjan Baizaqūly Älıbekov; russian: Канатжан Алибеков, Kanatzhan Alibekov; born 1950), known as Kenneth "Ken" Alibek since 1992, is a Kazak ...

and Matthew Meselson, were shown electron micrographs of the anthrax from the Daschle letter. In a November 5, 2002 letter to the editors of ''The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'' (also known as the ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'') is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C. It is the most widely circulated newspaper within the Washington metropolitan area and has a large n ...

'', they stated that they saw no evidence the anthrax spores had been coated with fumed silica.

In ''Science'' magazine, one group of scientists said that the material could have been made by someone knowledgeable with standard laboratory equipment. Another group said it "was a diabolical advance in biological weapons technology". The article describes "a technique used to anchor silica nanoparticles to the surface of spores" using "polymerized glass".

An August 2006 article in ''Applied and Environmental Microbiology'', written by Douglas Beecher of the FBI labs in Quantico, Virginia, states "Individuals familiar with the compositions of the powders in the letters have indicated that they were comprised simply of spores purified to different extents." The article also specifically criticizes "a widely circulated misconception" "that the spores were produced using additives and sophisticated engineering supposedly akin to military weapon production". The harm done by this misconception is described this way: "This idea is usually the basis for implying that the powders were inordinately dangerous compared to spores alone. The persistent credence given to this impression fosters erroneous preconceptions, which may misguide research and preparedness efforts and generally detract from the magnitude of hazards posed by simple spore preparations." Critics of the article complained that it did not provide supporting references.

False report of bentonite

In late October 2001, ABC chief investigative correspondent Brian Ross linked the anthrax sample toSaddam Hussein

Saddam Hussein ( ; ar, صدام حسين, Ṣaddām Ḥusayn; 28 April 1937 – 30 December 2006) was an Iraqi politician who served as the fifth president of Iraq from 16 July 1979 until 9 April 2003. A leading member of the revolution ...

because of its purportedly containing the unusual additive bentonite

Bentonite () is an absorbent swelling clay consisting mostly of montmorillonite (a type of smectite) which can either be Na-montmorillonite or Ca-montmorillonite. Na-montmorillonite has a considerably greater swelling capacity than Ca-m ...

. On October 26, Ross said, "sources tell ABCNEWS the anthrax in the tainted letter sent to Senate Majority Leader Tom Daschle was laced with bentonite. The potent additive is known to have been used by only one country in producing biochemical weapons—Iraq. ... is a trademark of Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein's biological weapons program ... The discovery of bentonite came in an urgent series of tests conducted at Fort Detrick

Fort Detrick () is a United States Army Futures Command installation located in Frederick, Maryland. Historically, Fort Detrick was the center of the U.S. biological weapons program from 1943 to 1969. Since the discontinuation of that program, i ...

, Maryland, and elsewhere." On October 28, Ross said that "despite continued White House denials, four well-placed and separate sources have told ABC News that initial tests on the anthrax by the U.S. Army at Fort Detrick, Maryland, have detected trace amounts of the chemical additives bentonite and silica", a charge that was repeated several times on October 28 and 29.

On October 29, 2001, White House spokesman Scott Stanzel "disputed reports that the anthrax sent to the Senate contained bentonite, an additive that ha been used in Iraqi President Saddam Hussein's biological weapons program". Stanzel said, "Based on the test results we have, no bentonite has been found". The same day, Major General John Parker at a White House briefing stated, "We do know that we found silica in the samples. Now, we don't know what that motive would be, or why it would be there, or anything. But there is silica in the samples. And that led us to be absolutely sure that there was no aluminum in the sample, because the combination of a silicate, plus aluminum, is sort of the major ingredients of bentonite." Just over a week later, Homeland Security Advisor Tom Ridge

Thomas Joseph Ridge (born August 26, 1945) is an American politician and author who served as the Assistant to the President for Homeland Security from 2001 to 2003, and the first United States Secretary of Homeland Security from 2003 to 2005. ...

in a White House press conference on November 7, 2001, stated, "The ingredient that we talked about before was silicon." Neither Ross at ABC nor anyone else publicly pursued any further claims about bentonite, despite Ross's original claim that "four well-placed and separate sources" had confirmed its detection.

Dispute over silicon content

Some of the anthrax spores (65–75%) in the anthrax attack letters contained silicon inside their spore coats. Silicon was even reportedly found inside the natural spore coat of a spore that was still inside the "mother germ", which was asserted to confirm that the element was not added after the spores were formed and purified, i.e., the spores were not "weaponized". In 2010, a Japanese study reported, "silicon (Si) is considered to be a "quasiessential" element for most living organisms. However, silicate uptake in bacteria and its physiological functions have remained obscure." The study showed that spores from some species can contain as much as 6.3% dry weight of silicates. "For more than 20 years, significant levels of silicon had been reported in spores of at least some ''Bacillus'' species, including those of ''Bacillus cereus'', a close relative of ''B. anthracis''." According to spore expert Peter Setlow, "Since silicate accumulation in other organisms can impart structural rigidity, perhaps silicate plays such a role for spores as well." The FBI lab concluded that 1.4% of the powder in the Leahy letter was silicon. Stuart Jacobson, a small-particle chemistry expert stated that:This is a shockingly high proportionScientists at thef silicon F, or f, is the sixth letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''ef'' (pronounced ), and the plural is ''efs''. Hist ...It is a number one would expect from the deliberate weaponization of anthrax, but not from any conceivable accidental contamination.

Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) is a federal research facility in Livermore, California, United States. The lab was originally established as the University of California Radiation Laboratory, Livermore Branch in 1952 in response ...

conducted experiments in an attempt to determine if the amount of silicon in the growth medium was the controlling factor which caused silicon to accumulate inside a spore's natural coat. The Livermore scientists tried 56 different experiments, adding increasingly high amounts of silicon to the media. All of their results were far below the 1.4% level of the attack anthrax, some as low as .001%. The conclusion was that something other than the level of silicon controlled how much silicon was absorbed by the spores.

Richard O. Spertzel Richard Oscar Spertzel (9 February 1933 – 24 March 2016) was a veterinarian, microbiologist and expert in the area of biological warfare. He participated in germ warfare research at U.S. Army Army Medical Unit, Medical Unit (USAMU), Fort Detrick, ...

, a microbiologist who led the United Nations' biological weapons inspections of Iraq, wrote that the anthrax used could not have come from the lab where Ivins worked. Spertzel said he remained skeptical of the Bureau's argument despite the new evidence presented on August 18, 2008, in an unusual FBI briefing for reporters. He questioned the FBI's claim that the powder was less than military grade, in part because of the presence of high levels of silica. The FBI had been unable to reproduce the attack spores with the high levels of silica. The FBI attributed the presence of high silica levels to "natural variability". This conclusion of the FBI contradicted its statements at an earlier point in the investigation, when the FBI had stated, based on the silicon content, that the anthrax was "weaponized", a step that made the powder more airy and required special scientific know-how.

"If there is that much silicon, it had to have been added," stated Jeffrey Adamovicz, who supervised Ivins's work at Fort Detrick. Adamovicz explained that the silicon in the anthrax attack could have been added via a large fermentor, which Battelle and some other facilities use but "we did not use a fermentor to grow anthrax at USAMRIID ... ndWe did not have the capability to add silicon compounds to anthrax spores." Ivins had neither the skills nor the means to attach silicon to anthrax spores. Spertzel explained that the Fort Detrick facility did not handle anthrax in powdered form. "I don't think there's anyone there who would have the foggiest idea how to do it."

Investigation

Authorities traveled to six continents, interviewed over 9,000 people, conducted 67 searches and issued over 6,000 subpoenas. "Hundreds of FBI personnel worked the case at the outset, struggling to discern whether the Sept. 11 al-Qaeda attacks and the anthrax murders were connected before eventually concluding that they were not." In September 2006, there were still 17 FBI agents and 10 postal inspectors assigned to the case, including FBI Special Agent

Authorities traveled to six continents, interviewed over 9,000 people, conducted 67 searches and issued over 6,000 subpoenas. "Hundreds of FBI personnel worked the case at the outset, struggling to discern whether the Sept. 11 al-Qaeda attacks and the anthrax murders were connected before eventually concluding that they were not." In September 2006, there were still 17 FBI agents and 10 postal inspectors assigned to the case, including FBI Special Agent C. Frank Figliuzzi

Cesare Frank Figliuzzi, Jr. (born September 12, 1962) is a former federal law enforcement agent. He is the former assistant director for counterintelligence at the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

who was the on-scene commander of the evidence recovery efforts.

Anthrax archive destroyed

The FBI andCenters for Disease Control and Prevention

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is the national public health agency of the United States. It is a United States federal agency, under the Department of Health and Human Services, and is headquartered in Atlanta, Georg ...

(CDC) both gave permission for Iowa State University to destroy the Iowa anthrax archive and the archive was destroyed on October 10 and 11, 2001.

The FBI and CDC investigation was hampered by the destruction of a large collection of anthrax spores collected over more than seven decades and kept in more than 100 vials at Iowa State University

Iowa State University of Science and Technology (Iowa State University, Iowa State, or ISU) is a public land-grant research university in Ames, Iowa. Founded in 1858 as the Iowa Agricultural College and Model Farm, Iowa State became one of the ...

, Ames, Iowa. Many scientists claim that the quick destruction of the anthrax spores collection in Iowa eliminated crucial evidence useful for the investigation. A precise match between the strain of anthrax used in the attacks and a strain in the collection would have offered hints as to when bacteria had been isolated and, perhaps, as to how widely it had been distributed to researchers. Such genetic clues could have given investigators the evidence necessary to identify the perpetrators.

Al-Qaeda and Iraq blamed for attacks

Immediately after the anthrax attacks,White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue Northwest, Washington, D.C., NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. preside ...

officials pressured FBI Director Robert Mueller

Robert Swan Mueller III (; born August 7, 1944) is an American lawyer and government official who served as the sixth director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) from 2001 to 2013.

A graduate of Princeton University and New York ...

to publicly blame them on al-Qaeda

Al-Qaeda (; , ) is an Islamic extremism, Islamic extremist organization composed of Salafist jihadists. Its members are mostly composed of Arab, Arabs, but also include other peoples. Al-Qaeda has mounted attacks on civilian and military ta ...

following the September 11 attacks

The September 11 attacks, commonly known as 9/11, were four coordinated suicide terrorist attacks carried out by al-Qaeda against the United States on Tuesday, September 11, 2001. That morning, nineteen terrorists hijacked four commerc ...

. During the president's morning intelligence briefings, Mueller was "beaten up" for not producing proof that the killer spores were the handiwork of Osama Bin Laden, according to a former aide. "They really wanted to blame somebody in the Middle East," the retired senior FBI official stated. The FBI knew early on that the anthrax used was of a consistency requiring sophisticated equipment and was unlikely to have been produced in "some cave". At the same time, President Bush and Vice President Cheney in public statements speculated about the possibility of a link between the anthrax attacks and Al Qaeda. ''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper

A newspaper is a periodical publication containing written information about current events and is often typed in black ink with a white or gray background.

Newspapers can cover a wide ...

'' reported in early October that American scientists had implicated Iraq as the source of the anthrax,Iraq 'behind US anthrax outbreaks'", David Rose and Ed Vulliamy, ''

The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper

A newspaper is a periodical publication containing written information about current events and is often typed in black ink with a white or gray background.

Newspapers can cover a wide ...

'', October 14, 2001 and the next day ''The Wall Street Journal

''The Wall Street Journal'' is an American business-focused, international daily newspaper based in New York City, with international editions also available in Chinese and Japanese. The ''Journal'', along with its Asian editions, is published ...

'' editorialized that Al Qaeda perpetrated the mailings, with Iraq the source of the anthrax. A few days later, John McCain suggested on the ''Late Show with David Letterman

The ''Late Show with David Letterman'' is an American late-night talk show hosted by David Letterman on CBS, the first iteration of the ''Late Show'' franchise. The show debuted on August 30, 1993, and was produced by Letterman's production c ...

'' that the anthrax may have come from Iraq, and the next week ABC News

ABC News is the journalism, news division of the American broadcast network American Broadcasting Company, ABC. Its flagship program is the daily evening newscast ''ABC World News Tonight, ABC World News Tonight with David Muir''; other progra ...

did a series of reports stating that three or four (depending on the report) sources had identified bentonite

Bentonite () is an absorbent swelling clay consisting mostly of montmorillonite (a type of smectite) which can either be Na-montmorillonite or Ca-montmorillonite. Na-montmorillonite has a considerably greater swelling capacity than Ca-m ...

as an ingredient in the anthrax preparations, implicating Iraq.

Statements by the White House and public officials quickly proved that there was no bentonite in the attack anthrax. "No tests ever found or even suggested the presence of bentonite. The claim was just concocted from the start. It just never happened." Nonetheless, a few conservative journalists repeated ABC's bentonite report for several years, even after the invasion of Iraq proved there was no involvement.

"Person of interest"

Barbara Hatch Rosenberg, a molecular biologist at the State University of New York at Purchase and chairwoman of a biological weapons panel at theFederation of American Scientists

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) is an American nonprofit global policy think tank with the stated intent of using science and scientific analysis to attempt to make the world more secure. FAS was founded in 1946 by scientists who ...

, and others began claiming that the attack might be the work of a "rogue CIA agent" in October 2001, as soon as it became known that the Ames strain of anthrax had been used in the attacks, and she told the FBI the name of the "most likely" person. On November 21, 2001, she made similar statements to the Biological and Toxic Weapons convention in Geneva. In December 2001, she published "A Compilation of Evidence and Comments on the Source of the Mailed Anthrax" via the web site of the Federation of American Scientists

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) is an American nonprofit global policy think tank with the stated intent of using science and scientific analysis to attempt to make the world more secure. FAS was founded in 1946 by scientists who ...

(FAS) claiming that the attacks were "perpetrated with the unwitting assistance of a sophisticated government program". She discussed the case with reporters from ''The New York Times''. On January 4, 2002, Nicholas Kristof of ''The New York Times'' published a column titled "Profile of a Killer" stating "I think I know who sent out the anthrax last fall." For months, Rosenberg gave speeches and stated her beliefs to many reporters from around the world. She posted "Analysis of the Anthrax Attacks" to the FAS web site on January 17, 2002. On February 5, 2002, she published "Is the FBI Dragging Its Feet?" In response, the FBI stated, "There is no prime suspect in this case at this time". ''The Washington Post'' reported, "FBI officials over the last week have flatly discounted Dr. Rosenberg's claims". On June 13, 2002, Rosenberg posted "The Anthrax Case: What the FBI Knows" to the FAS site. On June 18, 2002, she presented her theories to senate staffers working for Senators Daschle and Leahy. On June 25, the FBI publicly searched Steven Hatfill

Steven Jay Hatfill (born October 24, 1953) is an American physician, pathologist and biological weapons expert. He became the subject of extensive media coverage beginning in mid-2002, when he was a suspect in the 2001 anthrax attacks.Lichtblau, ...

's apartment, and he became a household name. "The FBI also pointed out that Hatfill had agreed to the search and is not considered a suspect." American Prospect and Salon.com reported, "Hatfill is not a suspect in the anthrax case, the FBI says." On August 3, 2002, Rosenberg told the media that the FBI asked her if "a team of government scientists could be trying to frame Steven J. Hatfill". In August 2002, Attorney General John Ashcroft

John David Ashcroft (born May 9, 1942) is an American lawyer, lobbyist and former politician who served as the 79th U.S. Attorney General in the George W. Bush administration from 2001 to 2005. A former U.S. Senator from Missouri and the 50t ...

labeled Hatfill a "person of interest

"Person of interest" is a term used by law enforcement in the United States, Canada, and other countries when identifying someone possibly involved in a criminal investigation who has not been arrested or formally accused of a crime. It has no le ...

" in a press conference, though no charges were brought against him. Hatfill is a virologist, and he vehemently denied that he had anything to do with the anthrax mailings and sued the FBI, the Justice Department, Ashcroft, Alberto Gonzales

Alberto R. Gonzales (born August 4, 1955) is an American lawyer who served as the 80th United States Attorney General, appointed in February 2005 by President George W. Bush, becoming the highest-ranking Hispanic American in executive govern ...

, and others for violating his constitutional rights and for violating the Privacy Act. On June 27, 2008, the Department of Justice announced that it would settle Hatfill's case for $5.8 million.

Hatfill also sued ''The New York Times'' and its columnist Nicholas D. Kristof, as well as Donald Foster, '' Vanity Fair'', ''Reader's Digest

''Reader's Digest'' is an American general-interest family magazine, published ten times a year. Formerly based in Chappaqua, New York, it is now headquartered in midtown Manhattan. The magazine was founded in 1922 by DeWitt Wallace and his w ...

'', and Vassar College

Vassar College ( ) is a private liberal arts college in Poughkeepsie, New York, United States. Founded in 1861 by Matthew Vassar, it was the second degree-granting institution of higher education for women in the United States, closely fol ...

for defamation. The case against ''The New York Times'' was initially dismissed, but it was reinstated on appeal. The dismissal was upheld by the appeals court on July 14, 2008, on the basis that Hatfill was a public figure and malice had not been proven. The Supreme Court rejected an appeal on December 15, 2008. Hatfill's lawsuits against ''Vanity Fair'' and ''Reader's Digest'' were settled out of court in February 2007, but no details were made public. The statement released by Hatfill's lawyers said, "Dr. Hatfill's lawsuit has now been resolved to the mutual satisfaction of all the parties".

Bruce Edwards Ivins

Bruce E. Ivins

Bruce Edwards Ivins (; April 22, 1946July 29, 2008) was an American microbiologist, vaccinologist, senior biodefense researcher at the United States Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID), Fort Detrick, Maryland, and ...

had worked for 18 years at the government's bio defense labs at Fort Detrick

Fort Detrick () is a United States Army Futures Command installation located in Frederick, Maryland. Historically, Fort Detrick was the center of the U.S. biological weapons program from 1943 to 1969. Since the discontinuation of that program, i ...

and was a top biodefense researcher. The Associated Press reported on August 1, 2008, that he had apparently committed suicide at the age of 62. It was widely reported that the FBI was about to press charges against him, but the evidence was largely circumstantial and the grand jury in Washington reported that it was not ready to issue an indictment. Rush D. Holt Jr.

Rush Dew Holt Jr. (born October 15, 1948) is an American scientist and politician who served as the U.S. representative for from 1999 to 2015. He is a member of the Democratic Party and son of former West Virginia U.S. Senator Rush D. Holt Sr. ...

represented the district where the anthrax letters were mailed, and he said that circumstantial evidence was not enough and asked FBI director Robert S. Mueller

Robert Swan Mueller III (; born August 7, 1944) is an American lawyer and government official who served as the sixth director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) from 2001 to 2013.

A graduate of Princeton University and New York U ...

to appear before Congress to provide an account of the investigation. Ivins's death left two unanswered questions. Scientists familiar with germ warfare said that there was no evidence that he had the skills to turn anthrax into an inhalable powder. Alan Zelicoff aided the FBI investigation, and he stated: "I don't think a vaccine specialist could do it…. This is aerosol physics, not biology".

W. Russell Byrne worked in the bacteriology division of the Fort Detrick research facility. He said that Ivins was "hounded" by FBI agents who raided his home twice, and he was hospitalized for depression during that time. According to Byrne and local police, Ivins was removed from his workplace out of fears that he might harm himself or others. "I think he was just psychologically exhausted by the whole process," Byrne said. "There are people who you just know are ticking bombs. He was not one of them."

On August 6, 2008, federal prosecutors declared Ivins the sole perpetrator of the crime when US Attorney Jeffrey A. Taylor

Jeffrey A. Taylor is the former interim United States Attorney for the District of Columbia. He is a graduate of Stanford University and Harvard Law School.

Career

Prior to his work in Washington, DC, Jeffrey Taylor served as an Assistant U.S. A ...

laid out the case to the public. "The genetically unique parent material of the anthrax spores... was created and solely maintained by Dr. Ivins." But other experts disagreed, including biological warfare and anthrax expert Meryl Nass

Meryl is a given name, and may refer to:

In people:

* Meryl, a musical artist originating from the Martinique

* Meryl Cassie (born 1984), New Zealand actress

* Meryl Davis (born 1987), American ice dancer

* Meryl Fernandes (born 1983), British ...

, who stated: "Let me reiterate: no matter how good the microbial forensics may be, they can only, at best, link the anthrax to a particular strain and lab. They ''cannot'' link it to any individual." At least 10 scientists had regular access to the laboratory and its anthrax stock, and possibly quite a few more, counting visitors from other institutions and workers at laboratories in Ohio and New Mexico that had received anthrax samples from the flask. The FBI later claimed to have identified 419 people at Fort Detrick and other locations w