1989–1991 Ukrainian Revolution on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

From the formal establishment of the

By August 1989, Shcherbytsky's position within the Communist Party was tenuous. On one hand was intense pressures from the strikes, while on the other hand, as one of the last three remaining Brezhnevites to hold office in the Soviet Union, the

By August 1989, Shcherbytsky's position within the Communist Party was tenuous. On one hand was intense pressures from the strikes, while on the other hand, as one of the last three remaining Brezhnevites to hold office in the Soviet Union, the

1991 brought further victories for Rukh and the protest movement. On 17 March 1991 Ukraine's declaration of state sovereignty was confirmed in a

1991 brought further victories for Rukh and the protest movement. On 17 March 1991 Ukraine's declaration of state sovereignty was confirmed in a

People's Movement of Ukraine

The People's Movement of Ukraine () is a Ukraine, Ukrainian political party and one of the first Opposition (politics), opposition parties in Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, Soviet Ukraine.The first officially registered opposition politica ...

on 1 July 1989 to the formalisation of the Declaration of Independence of Ukraine

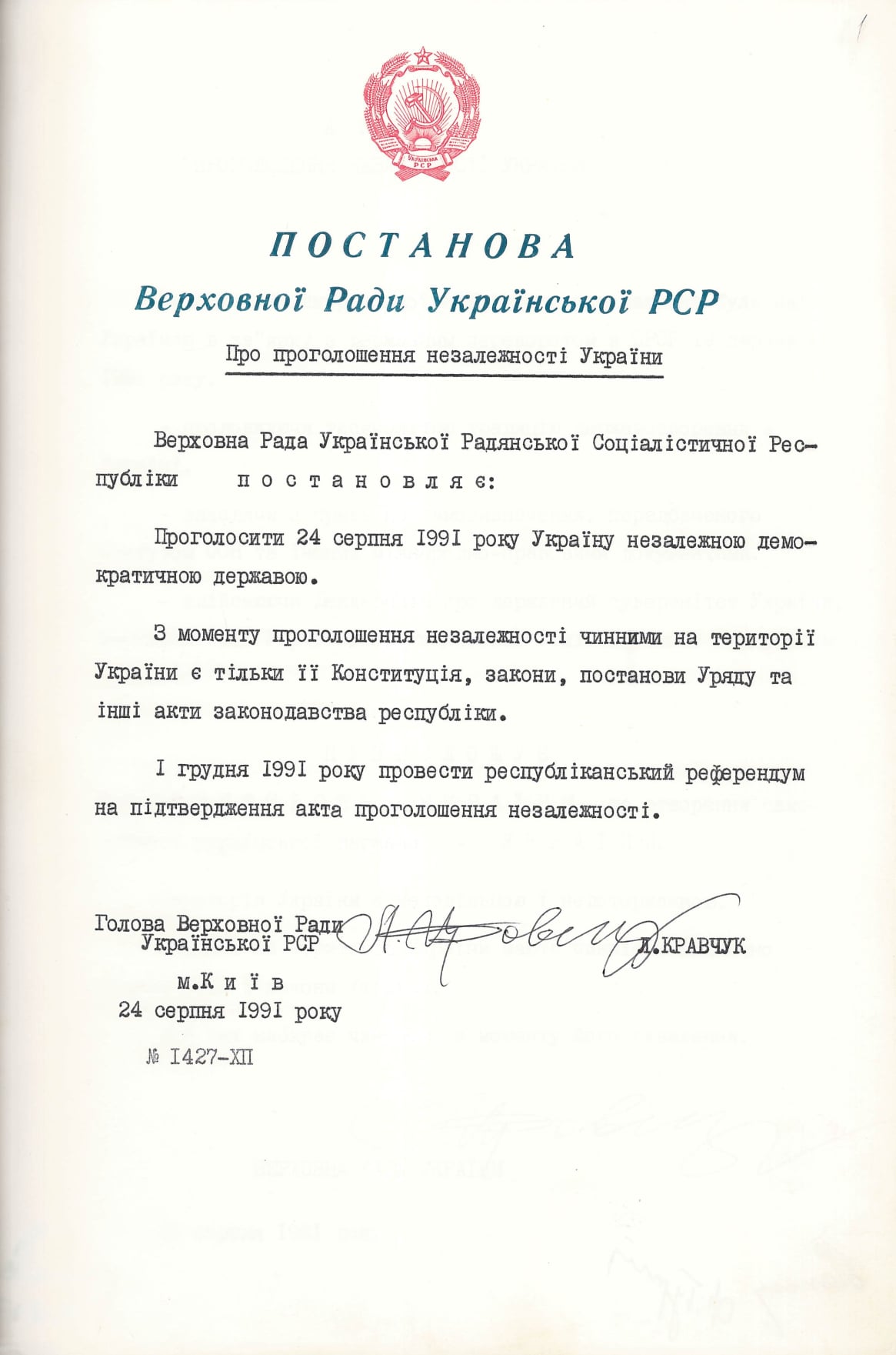

The Act of Declaration of Independence of Ukraine was adopted by the Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian SSR (''Verkhovna Rada'') on 24 August 1991.referendum

A referendum, plebiscite, or ballot measure is a Direct democracy, direct vote by the Constituency, electorate (rather than their Representative democracy, representatives) on a proposal, law, or political issue. A referendum may be either bin ...

on 1 December 1991, a non-violent protest movement worked to achieve Ukrainian independence from the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

. Led by Soviet dissident

Soviet dissidents were people who disagreed with certain features of Soviet ideology or with its entirety and who were willing to speak out against them. The term ''dissident'' was used in the Soviet Union (USSR) in the period from the mid-1960s ...

Viacheslav Chornovil

Viacheslav Maksymovych Chornovil (; 24 December 1937 – 25 March 1999) was a Ukrainian Soviet dissident, independence activist and politician who was the leader of the People's Movement of Ukraine from 1989 until his death in 1999. He spent fi ...

, the protests began as a series of strikes in the Donbas

The Donbas (, ; ) or Donbass ( ) is a historical, cultural, and economic region in eastern Ukraine. The majority of the Donbas is occupied by Russia as a result of the Russo-Ukrainian War.

The word ''Donbas'' is a portmanteau formed fr ...

that led to the removal of longtime communist leader Volodymyr Shcherbytsky

Volodymyr Vasyliovych Shcherbytsky (17 February 1918 – 16 February 1990) was a Ukrainian Soviet politician who served as First Secretary of the Ukrainian Communist Party from 1972 to 1989. A close ally of Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev, Sh ...

. Later, the protests grew in size and scope, leading to a human chain across the country and widespread student protests against the falsification of the 1990 Ukrainian Supreme Soviet election

Supreme Soviet elections were held in the Ukrainian SSR on 4 March 1990, with runoffs in some seats held between 10 and 18 March. The elections were held to elect deputies to the republic's parliament, the Verkhovna Rada. Simultaneously, election ...

. The protests were ultimately successful, leading to the independence of Ukraine amidst the broader dissolution of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union was formally dissolved as a sovereign state and subject of international law on 26 December 1991 by Declaration No. 142-N of the Soviet of the Republics of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union. Declaration No. 142-Н of ...

.

Marked by widespread displays of support for the cause of Ukrainian independence, the revolution ultimately acquired the support of large numbers of the population and ruling Communist Party elite, allowing Ukraine to become independent from the Soviet Union peacefully. Its causes include a mix of economic and political justifications, primarily relating to economic downturn and mismanagement, Russification

Russification (), Russianisation or Russianization, is a form of cultural assimilation in which non-Russians adopt Russian culture and Russian language either voluntarily or as a result of a deliberate state policy.

Russification was at times ...

, and authoritarianism during the Era of Stagnation

The "Era of Stagnation" (, or ) is a term coined by Mikhail Gorbachev in order to describe the negative way in which he viewed the economic, political, and social policies of the Soviet Union that began during the rule of Leonid Brezhnev (1964 ...

and Shcherbytsky's 17-year rule. After the revolution, the democratic movement failed to replicate its successes in independent Ukraine, a fact owed to the splintering of the movement along ideological lines and the achievement of its primary goal. The revolution continues to be celebrated in present-day Ukraine, and the Independence Day of Ukraine

Independence Day of Ukraine (, ) is a public holidays in Ukraine, state holiday in Ukraine, celebrated on 24 August in commemoration of the Declaration of Independence of Ukraine, Declaration of Independence of 1991.

History

When Ukraine was st ...

is a national holiday.

Background

Ukraine became independent from Russia as theUkrainian People's Republic

The Ukrainian People's Republic (UPR) was a short-lived state in Eastern Europe. Prior to its proclamation, the Central Council of Ukraine was elected in March 1917 Ukraine after the Russian Revolution, as a result of the February Revolution, ...

in 1917. Divided in 1921 between the Second Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, at the time officially known as the Republic of Poland, was a country in Central and Eastern Europe that existed between 7 October 1918 and 6 October 1939. The state was established in the final stage of World War I ...

and Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

, the remaining western portion of Ukraine was further annexed

Annexation, in international law, is the forcible acquisition and assertion of legal title over one state's territory by another state, usually following military occupation of the territory. In current international law, it is generally held to ...

by the Soviet Union as part of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, officially the Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, and also known as the Hitler–Stalin Pact and the Nazi–Soviet Pact, was a non-aggression pact between Nazi Ge ...

and formalised by the 1945 Potsdam Conference. 3.5 to 5 million Ukrainians were killed in the 1932–1933 Holodomor

The Holodomor, also known as the Ukrainian Famine, was a mass famine in Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, Soviet Ukraine from 1932 to 1933 that killed millions of Ukrainians. The Holodomor was part of the wider Soviet famine of 1930–193 ...

, a famine created by the Soviet government. Present-day historians debate whether the famine was an act of genocide

Genocide is violence that targets individuals because of their membership of a group and aims at the destruction of a people. Raphael Lemkin, who first coined the term, defined genocide as "the destruction of a nation or of an ethnic group" by ...

against Ukrainians, a result of collectivisation in the Soviet Union, or an unintentional byproduct of collectivisation that was subsequently weaponised against Ukrainians. Ukrainians fought in both the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

and the Ukrainian Insurgent Army

The Ukrainian Insurgent Army (, abbreviated UPA) was a Ukrainian nationalist partisan formation founded by the Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) on 14 October 1942. The UPA launched guerrilla warfare against Nazi Germany, the S ...

(which was at various points allied with or fighting against Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

) during World War II. The Ukrainian Insurgent Army continued to fight the Soviets after the war until 1949, though some units continued fighting until 1956.

During the Era of Stagnation

The "Era of Stagnation" (, or ) is a term coined by Mikhail Gorbachev in order to describe the negative way in which he viewed the economic, political, and social policies of the Soviet Union that began during the rule of Leonid Brezhnev (1964 ...

, the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, abbreviated as the Ukrainian SSR, UkrSSR, and also known as Soviet Ukraine or just Ukraine, was one of the Republics of the Soviet Union, constituent republics of the Soviet Union from 1922 until 1991. ...

was ruled by First Secretary Volodymyr Shcherbytsky

Volodymyr Vasyliovych Shcherbytsky (17 February 1918 – 16 February 1990) was a Ukrainian Soviet politician who served as First Secretary of the Ukrainian Communist Party from 1972 to 1989. A close ally of Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev, Sh ...

, a close ally of Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev

Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev (19 December 190610 November 1982) was a Soviet politician who served as the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1964 until Death and state funeral of Leonid Brezhnev, his death in 1982 as w ...

and a member of his Dnipropetrovsk Mafia

The Dnipropetrovsk Mafia, also known as the Dnipropetrovsk clan (; ) or simply ''Dnipropetrovtsi'' (), is a group of Ukrainian oligarchs, politicians, and Ukrainian mafia, organised crime figures, and formerly Soviet politicians. While two separ ...

political clique. Shcherbytsky took aim at nationally minded members of the Ukrainian intelligentsia; a 1973–1975 purge of the Communist Party of Ukraine

The Communist Party of Ukraine (CPU or KPU) is a banned political party in Ukraine. It was founded in 1993 and claimed to be the successor to the Soviet-era Communist Party of Ukraine, which had been banned in 1991. In 2002 it held a "unifi ...

resulted in the removal of around 5% of the party's members, and every member of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group

The Ukrainian Helsinki Group () was founded on November 9, 1976, as the Ukrainian Public Group to Promote the Implementation of the Helsinki Accords on Human Rights () to monitor human rights in Ukraine. The group was active until 1981 when all ...

of human rights activists was arrested and deported to labour camps. This was matched by a general crackdown on Ukrainian culture, a purge of Ukrainian academia and cultural institutions, and the systematic targeting of the Ukrainian language by the government. The 1979 removal of , who had overseen the purges, did little to stem the tide of Russification, and further events celebrating the Russification of Ukraine occurred in 1982.

On top of political concerns, the Ukrainian economy continued to decline throughout the 1970s and 1980s, particularly in the eastern Donbas

The Donbas (, ; ) or Donbass ( ) is a historical, cultural, and economic region in eastern Ukraine. The majority of the Donbas is occupied by Russia as a result of the Russo-Ukrainian War.

The word ''Donbas'' is a portmanteau formed fr ...

region, where metallurgy and coal mining were the main economic activities. The shift from coal to nuclear power devastated the local economy, and a combination of overly-centralised collective farms and droughts negatively affected Ukraine's agricultural economy. The 1986 Chernobyl disaster

On 26 April 1986, the no. 4 reactor of the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant, located near Pripyat, Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, Ukrainian SSR, Soviet Union (now Ukraine), exploded. With dozens of direct casualties, it is one of only ...

further galvanised growing opposition to the Soviet government in Ukraine. The liberalisation of Soviet society as part of Perestroika

''Perestroika'' ( ; rus, перестройка, r=perestrojka, p=pʲɪrʲɪˈstrojkə, a=ru-perestroika.ogg, links=no) was a political reform movement within the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) during the late 1980s, widely associ ...

allowed greater room for free expression and self-identification, but the majority of these changes did not affect Ukraine to the same extent as other Soviet republics, or other countries within the Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc (Combloc), the Socialist Bloc, the Workers Bloc, and the Soviet Bloc, was an unofficial coalition of communist states of Central and Eastern Europe, Asia, Africa, and Latin America that were a ...

. In 1989, however, Ukrainian pro-independence activity exploded, particularly in Western Ukraine, which had little experience being under Russia compared to other parts of Ukraine.

History

Strikes, removal of Shcherbytsky, foundation of Rukh (1989)

A series of strikes by coal miners began in the Donbas on 18 July 1989, spurred by simultaneous strikes by miners in the Kuzbass region of Russia. The strikes, while based primarily on economic misfortunes, were also pro-independence in nature; the leaders of the strikes expressed overt support for the independence of Ukraine from the Soviet Union, so that the country could better manage its own economy. The response from Shcherbytsky's government was to use state media to discredit the strikers and restrict information about the spread of the strikes. The demands of the strikes became more overtly political, calling for the resignation of Shcherbytsky and Valentyna Shevchenko,Chairman of the Verkhovna Rada

The chairman of the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine () is the presiding officer of the Verkhovna Rada, Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the List of European countries by area, second-largest country in Europe after Russi ...

.

By August 1989, Shcherbytsky's position within the Communist Party was tenuous. On one hand was intense pressures from the strikes, while on the other hand, as one of the last three remaining Brezhnevites to hold office in the Soviet Union, the

By August 1989, Shcherbytsky's position within the Communist Party was tenuous. On one hand was intense pressures from the strikes, while on the other hand, as one of the last three remaining Brezhnevites to hold office in the Soviet Union, the Central Committee of the CPSU

The Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union was the Central committee, highest organ of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) between Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Congresses. Elected by the ...

was simultaneously pushing for his resignation. In September 1989 he was removed from the Central Committee, and days later he was replaced as First Secretary of the KPU by Vladimir Ivashko

Vladimir Antonovich Ivashko (; , ''Volodymyr Antonovych Ivashko''; 28 October 1932 – 13 November 1994) was a Soviet Ukrainian politician, briefly acting as General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) during the perio ...

. Shevchenko also later resigned.

Firing Shcherbytsky, however, did not stem the tide of activism. The People's Movement of Ukraine for Perestroika, founded days before Shcherbytsky's ouster by dissident leader Viacheslav Chornovil

Viacheslav Maksymovych Chornovil (; 24 December 1937 – 25 March 1999) was a Ukrainian Soviet dissident, independence activist and politician who was the leader of the People's Movement of Ukraine from 1989 until his death in 1999. He spent fi ...

, was approved on the initiative of Leonid Kravchuk

Leonid Makarovych Kravchuk (, ; 10 January 1934 – 10 May 2022) was a Ukrainian politician and the first president of Ukraine, serving from 5 December 1991 until 19 July 1994. In 1992, he signed the Lisbon Protocol, undertaking to give up Ukrai ...

(at the time the only member of the Central Committee of the KPU who could speak Ukrainian). The People's Movement, or ''Rukh'' (), was inspired by similar national organisations in other republics, particularly Sąjūdis

The Sąjūdis (, ), initially known as the Reform Movement of Lithuania (), is a political organisation which led the struggle for Lithuanian independence in the late 1980s and early 1990s. It was established on 3 June 1988 as the first oppositi ...

in Lithuania. An earlier attempt in 1988 had been suppressed, and the name of this attempt had been chosen deliberately to convey the concept that Rukh was not in opposition to the CPSU, but rather in support of it.

Other protests against Shcherbytsky were held throughout the year, including protests against the Chernobyl disaster

On 26 April 1986, the no. 4 reactor of the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant, located near Pripyat, Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, Ukrainian SSR, Soviet Union (now Ukraine), exploded. With dozens of direct casualties, it is one of only ...

. The Chernobyl disaster became a rallying cry for protesters, being invoked as an effort to demonstrate the urgency of the situation.

Human chain, Revolution on Granite, Zaporozhian Sich anniversary (1990)

The next year brought increasing protests. On 21 January 1990, the anniversary of the 1919Unification Act

The Unification Act (, ; or , ) was an agreement signed by the Ukrainian People's Republic and the West Ukrainian People's Republic in Sophia Square in Kyiv on 22 January 1919. Since 1999, it is celebrated every year as the Day of Unity of Ukr ...

between the Ukrainian People's Republic and West Ukrainian People's Republic

The West Ukrainian People's Republic (; West Ukrainian People's Republic#Name, see other names) was a short-lived state that controlled most of Eastern Galicia from November 1918 to July 1919. It included major cities of Lviv, Ternopil, Kolom ...

, a human chain of three million people linked the western Ukrainian city of Lviv

Lviv ( or ; ; ; see #Names and symbols, below for other names) is the largest city in western Ukraine, as well as the List of cities in Ukraine, fifth-largest city in Ukraine, with a population of It serves as the administrative centre of ...

to Kyiv

Kyiv, also Kiev, is the capital and most populous List of cities in Ukraine, city of Ukraine. Located in the north-central part of the country, it straddles both sides of the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2022, its population was 2, ...

, Ukraine's capital. The human chain, which also drew hundreds of thousands of protesters to Sophia Square in Kyiv, demonstrated the popularity of Ukrainian independence outside of Western Ukraine. It was the largest demonstration in late-Soviet era Ukraine.

The first multi-party elections to the Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic

The Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian SSR (; ) was the Supreme Soviet, supreme soviet (main Legislature, legislative institution) and the highest organ of state power of Ukraine when it was known as the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic (Ukra ...

were held in March 1990. The Democratic Bloc, led by protester Ihor Yukhnovskyi

Ihor Rafailovych Yukhnovskyi (; also Yukhnovsky; 1 September 1925 – 26 March 2024) was a Ukrainian physicist and politician, and a member of the Presidium of Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, Hero of Ukraine.

Life before politics

Yukhnovskyi ...

, won 111 seats to the KPU's 331. The new Supreme Soviet in July 1990 passed the Declaration of State Sovereignty of Ukraine

The Declaration of State Sovereignty of Ukraine (, ) was adopted on July 16, 1990, by the recently elected parliament of Ukrainian SSR by a vote of 355 for and four against.

The document decreed that Ukrainian SSR laws took precedence over the l ...

, by which the Ukrainian SSR gave itself the right to establish an army, central bank, and currency. The declaration further established Ukrainian citizenship

Ukrainian nationality law details the conditions by which a person holds nationality of Ukraine. The primary law governing these requirements is the law "On Citizenship of Ukraine", which came into force on 1 March 2001.

Any person born to at ...

, established the supremacy of Ukrainian laws over the laws of the central Soviet government in case of a dispute, and expressed the intentions to become a neutral

Neutral or neutrality may refer to:

Mathematics and natural science Biology

* Neutral organisms, in ecology, those that obey the unified neutral theory of biodiversity

Chemistry and physics

* Neutralization (chemistry), a chemical reaction in ...

and non-nuclear state.

However, a group of students led by Oles Donii protested the results of the election, claiming that the Democratic Bloc had enough support to gain a majority of seats. On 2 October 1990, a group of students began occupying the October Revolution Square in central Kyiv and launched a hunger strike. As part of their demands, they sought free and fair elections to the Supreme Soviet, the nationalisation of property owned by the KPU, and the resignation of Chairman of the Council of Ministers Vitaliy Masol

Vitaliy Andriyovych Masol (; 14 November 1928 – 21 September 2018) was a Soviet-Ukrainian politician who served as leader of the Ukrainian government on two occasions. He held various posts in the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, most not ...

. They also sought to prevent the signing of the New Union Treaty

The New Union Treaty () was a draft treaty that would have replaced the 1922 Treaty on the Creation of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) to salvage and reform the USSR. A ceremony of the Russian SFSR signing the treaty was scheduled ...

by the Ukrainian SSR and the stationing of Ukrainian conscripts of the Soviet Army

The Soviet Ground Forces () was the land warfare service branch of the Soviet Armed Forces from 1946 to 1992. It was preceded by the Red Army.

After the Soviet Union ceased to exist in December 1991, the Ground Forces remained under th ...

outside Ukraine. The protests garnered the attention of the Ukrainian public, and supporters of the protests came to October Revolution Square in a demonstration of solidarity with the students. Other organisations that were not already on strike moved to do so as a further show of support.

Fears held by protesters of a crackdown ultimately failed to emerge, and many of the Supreme Soviet's deputies sided with the students. After Kravchuk allowed Donii to express his demands within the Supreme Soviet on 15 October, the government acquiesced two days later. The same day, Masol resigned as Chairman of the Council of Ministers, and was replaced by Vitold Fokin

Vitold Pavlovych Fokin (; 25 October 1932 – 20 March 2025) was a Ukrainian politician who served as the first Prime Minister of Ukraine from the country's declaration of independence on 24 August 1991 until 1 October 1992. He had earlier ser ...

.

At the same time, Ukrainian independence activists were organising in less confrontational ways, including cooperation with the Soviet Ukrainian government on celebrating the 500th anniversary of the Zaporozhian Sich

The 500th anniversary of the Zaporozhian Sich () was a group of celebrations organised by the and People's Movement of Ukraine and held in August 1990 to commemorate the 500th anniversary of the founding of the Zaporozhian Sich. The events, wh ...

. As part of the three-day celebration in August 1990, soldiers of the Soviet Army

The Soviet Ground Forces () was the land warfare service branch of the Soviet Armed Forces from 1946 to 1992. It was preceded by the Red Army.

After the Soviet Union ceased to exist in December 1991, the Ground Forces remained under th ...

helped install the flag of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army

The flag of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (), also known as the red-and-black flag (), is a flag previously used by the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) and the Banderite, Bandera wing of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN), and now ...

and provide accommodations for participants, while events included commemorations of Cossack leader Ivan Sirko

Ivan Dmytrovych Sirko ( – August 11, 1680) was a Zaporozhian Cossack military leader, Koshovyi Otaman of the Zaporozhian Host and putative co-author of the famous semi-legendary Cossack letter to the Ottoman sultan that inspired the major p ...

and historian Dmytro Yavornytsky, a gathering of Cossack groups from throughout Ukraine, a scientific conference discussing the Zaporozhian Sich, and a 500,000-member march in the city of Zaporizhzhia

Zaporizhzhia, formerly known as Aleksandrovsk or Oleksandrivsk until 1921, is a city in southeast Ukraine, situated on the banks of the Dnieper, Dnieper River. It is the Capital city, administrative centre of Zaporizhzhia Oblast. Zaporizhzhia ...

. These celebrations helped to cement Cossacks as a part of the Ukrainian national consciousness.

Independence (1991)

1991 brought further victories for Rukh and the protest movement. On 17 March 1991 Ukraine's declaration of state sovereignty was confirmed in a

1991 brought further victories for Rukh and the protest movement. On 17 March 1991 Ukraine's declaration of state sovereignty was confirmed in a referendum

A referendum, plebiscite, or ballot measure is a Direct democracy, direct vote by the Constituency, electorate (rather than their Representative democracy, representatives) on a proposal, law, or political issue. A referendum may be either bin ...

, with 81.69% voting in favour. , held in the Lviv

Lviv ( or ; ; ; see #Names and symbols, below for other names) is the largest city in western Ukraine, as well as the List of cities in Ukraine, fifth-largest city in Ukraine, with a population of It serves as the administrative centre of ...

, Ivano-Frankivsk

Ivano-Frankivsk (, ), formerly Stanyslaviv, Stanislav and Stanisławów, is a city in western Ukraine. It serves as the administrative centre of Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast as well as Ivano-Frankivsk Raion within the oblast. Ivano-Frankivsk also host ...

, and Ternopil

Ternopil, known until 1944 mostly as Tarnopol, is a city in western Ukraine, located on the banks of the Seret River. Ternopil is one of the major cities of Western Ukraine and the historical regions of Galicia and Podolia. The populatio ...

oblasts (regions) alongside the sovereignty referendum, demonstrated 88.3% voting in favour. The growing scale of the protests drew the attention of United States President George H. W. Bush

George Herbert Walker BushBefore the outcome of the 2000 United States presidential election, he was usually referred to simply as "George Bush" but became more commonly known as "George H. W. Bush", "Bush Senior," "Bush 41," and even "Bush th ...

, who urged Ukrainians to stop pursuing independence in a 1 August 1991 speech. The speech, which was criticised by Ukrainian nationalists and American conservatives, urged Ukrainians not to pursue "suicidal nationalism", a phrase also used by Gorbachev.

However, the process of independence was rapidly accelerated later that month by the 1991 Soviet coup d'état attempt

The 1991 Soviet coup attempt, also known as the August Coup, was a failed attempt by hardliners of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) to Coup d'état, forcibly seize control of the country from Mikhail Gorbachev, who was President ...

. After a group of Soviet hardliners attempted to overthrow Gorbachev on 19 August, there were widespread protests against the coup attempt in Ukraine. Gorbachev's return to power failed to stop the ensuing chaos, and on 24 August 1991, the Supreme Soviet ratified the Declaration of Independence of Ukraine

The Act of Declaration of Independence of Ukraine was adopted by the Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian SSR (''Verkhovna Rada'') on 24 August 1991.Levko Lukianenko, Mykhailo Horyn, Serhiy Holovatyi, and . The KPU agreed to the declaration of independence at the urging of Kravchuk, with First Secretary

A History of Ukraine: The Land and Its Peoples

by

Stanislav Hurenko

Stanislav Ivanovych Hurenko (; ; 30 May 1936 – 14 April 2013) was a Soviet and Ukrainian politician. He was a member of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.

Biography

Mikhail Gorbachev brought in his ally Hurenko in to replace Vladimi ...

saying that opposing independence would be a "disaster." In an effort to placate anti-independence communist hardliners, pro-independence deputies Volodymyr Yavorivsky and Dmytro Pavlychko put forward the concept of a referendum to confirm the declaration of independence. The flag of the Soviet Union

The State Flag of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, also simply known as the Soviet flag or the Red Banner, was a Red flag (politics), red flag with two Communist symbolism, communist symbols displayed in the Canton (flag), canton: a gold ...

was removed from government buildings and replaced with the flag of Ukraine

The national flag of Ukraine (, ) consists of equally sized horizontal bands of blue and yellow.

The blue and yellow bicolor flag was first seen during the 1848 Spring of Nations in Lemberg (Lviv), the capital of the Kingdom of Galicia and Lo ...

, an amnesty for all political prisoners was signed, the KPU was suspended and its assets were frozen in connection with the coup attempt. October Revolution Square was renamed to ''Maidan Nezalezhnosti'' (), while The referendum

A referendum, plebiscite, or ballot measure is a Direct democracy, direct vote by the Constituency, electorate (rather than their Representative democracy, representatives) on a proposal, law, or political issue. A referendum may be either bin ...

proposed by Yavorivsky and Pavlychko ultimately occurred, with 92.26% of votes in favour.Dieter Nohlen

Dieter Nohlen (born 6 November 1939) is a German academic and political scientist. He currently holds the position of Emeritus Professor of Political Science in the Faculty of Economic and Social Sciences of the University of Heidelberg. An ex ...

& Philip Stöver (2010) ''Elections in Europe: A data handbook'', page 1976

Legacy

The 1989–1991 revolution led to the establishment of present-day Ukraine. Sometimes referred to as the "National Liberation Revolution" () within the country, it led to the establishment of the country's political system. Ultimately, however, Rukh (and the broader democratic nationalist movement) failed to replicate the success it achieved in the revolution. Ukrainian politician has attributed these later failures to the success of the revolution, saying to ''Ukrainska Pravda

''Ukrainska Pravda'' is a Ukrainian socio-political online media outlet founded by Heorhii Gongadze in April 2000. After Gongadze’s death in September 2000, the editorial team was led by co-founder Olena Prytula, who remained the editor-in ...

'' in 2009, "I would attribute this to objective things, namely that we achieved statehood." The Declaration of Independence is celebrated yearly with the Independence Day of Ukraine

Independence Day of Ukraine (, ) is a public holidays in Ukraine, state holiday in Ukraine, celebrated on 24 August in commemoration of the Declaration of Independence of Ukraine, Declaration of Independence of 1991.

History

When Ukraine was st ...

.by

Paul Robert Magocsi

Paul Robert Magocsi (; born January 26, 1945) is an American professor of history, political science, and Chair of Ukrainian Studies at the University of Toronto. He has been with the university since 1980 and became a Fellow of the Royal Societ ...

, University of Toronto Press

The University of Toronto Press is a Canadian university press. Although it was founded in 1901, the press did not actually publish any books until 1911.

The press originally printed only examination books and the university calendar. Its first s ...

, 2010, (page 722/723)See also

*Democracy in Europe

Democracy in Europe can be comparatively assessed according to various definitions of democracy. According to the V-Dem Democracy Indices, the European countries with the highest democracy scores in 2023 are Denmark, Norway and Sweden, meanwhil ...

References