1937 Social Credit Backbenchers' Revolt on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The 1937 Social Credit backbenchers' revolt took place from March to June 1937 in the Canadian

The 1937 Social Credit backbenchers' revolt took place from March to June 1937 in the Canadian

During the

During the

Despite this statement, the Social Credit caucus invited Hargrave to explain his plan, which he did to the approval of many caucus members. Attorney-General John Hugill pointed out that the plan was unconstitutional, to which Hargrave replied that he was "not interested in legal arguments." Two weeks later, Hargrave left the province, telling the press that he "found it impossible to co-operate with a government which e considereda mere vacillating machine."Elliott 255 In this message, some MLAs found confirmation of their misgivings about Aberhart. A group of them, reported as numbering anywhere from five ("soon joined by eight or ten others") to 22,Brennan 48Barr 102 or 30Schultz 5 held meetings in

Despite this statement, the Social Credit caucus invited Hargrave to explain his plan, which he did to the approval of many caucus members. Attorney-General John Hugill pointed out that the plan was unconstitutional, to which Hargrave replied that he was "not interested in legal arguments." Two weeks later, Hargrave left the province, telling the press that he "found it impossible to co-operate with a government which e considereda mere vacillating machine."Elliott 255 In this message, some MLAs found confirmation of their misgivings about Aberhart. A group of them, reported as numbering anywhere from five ("soon joined by eight or ten others") to 22,Brennan 48Barr 102 or 30Schultz 5 held meetings in

Surprised by Aberhart's refusal to be involved in open conflict, the insurgents needed time to reassess their strategy. On March 17, Lieutenant-Governor Primrose died, necessitating a five-day adjournment of the legislature while the federal government selected a replacement. When the legislature reconvened on March 22Elliott 259 or 23, the dissidents

Surprised by Aberhart's refusal to be involved in open conflict, the insurgents needed time to reassess their strategy. On March 17, Lieutenant-Governor Primrose died, necessitating a five-day adjournment of the legislature while the federal government selected a replacement. When the legislature reconvened on March 22Elliott 259 or 23, the dissidents

Historians have taken different approaches to analyzing the effect of the Board on traditional Westminster parliamentary governance. Political scientist C. B. MacPherson emphasized "the extent to which the cabinet had abdicated in favour of a board composed of a few private members of the legislature", Byrne agrees that "in some respects, the powers granted to the board superseded those of the Executive Council" but notes that "Aberhart was permitted to carry on with regular government operations."Byrne 172 Elliott and Miller take a similar approach to MacPherson's, suggesting that "Aberhart and his cabinet ... were in a position, strange in a cabinet system of government, of being ruled in the matter of economic policy by a board of private members that would be under the influence of Social Credit 'experts'." Barr disagrees, arguing that the Board was "still under the control of cabinet" and pointing out that "the cabinet was left with the power", through its privileged position in introducing legislation, "to supplement or alter the provisions of the ''Alberta Social Credit Act''" under which terms the board was constituted.

The cabinet disavowed any ownership of the act that established the Board. Though it was a government bill, the Provincial Treasurer explained that he took no responsibility for it, as it was drawn up by a committee of insurgents "without the interference of the cabinet". Though some insurgents complained that the version of the bill introduced by the government was different than that drafted by the committee, MacLachlan insisted that there had been no material changes. The bill was passed April 13, and the legislature adjourned the following day.MacPherson 173

MacLachlan travelled to England to invite Douglas to become head of the expert commission. Douglas refused but provided two of the experts the Board was charged with finding: L. D. Byrne, who was appointed to do most of the substantive work of creating the program, and George Frederick Powell, who was in charge of the commission's public relations.Elliott 264 MLAs returned to their constituencies during the legislative break, making it difficult for the insurgents to organise. Aberhart addressed his supporters in his weekly radio address, encouraging people to tell their MLAs to support him or force an election. Aberhart's supporters followed his instructions causing arguments at meetings between the insurgents and the loyalists. Aberhart fired William Chant, a known Douglasite, from his cabinet after he refused to resign.Elliott 263 A petition calling for Aberhart's resignation circulated among backbenchers, and proved to be a plant by the cabinet to test MLAs' loyalty. Outwardly, however, the Social Crediters showed a united front as they awaited the promised experts; in the first recorded vote after the legislature reconvened June 7, all insurgents present voted with the government, though 13 were absent.

One of Powell's first actions on arriving in Edmonton was to prepare a "loyalty pledge" committing its signatories "to uphold the Social Credit Board and its technicians." Most Social Credit MLAs signed, and the six who did not wrote to Powell assuring him of their loyalty to Douglas's objectivesMacPherson 51 (though one, former Provincial Treasurer Cockroft, later left the Social Credit League and unsuccessfully sought re-election as an "Independent Progressive").Brennan 51

Historians have taken different approaches to analyzing the effect of the Board on traditional Westminster parliamentary governance. Political scientist C. B. MacPherson emphasized "the extent to which the cabinet had abdicated in favour of a board composed of a few private members of the legislature", Byrne agrees that "in some respects, the powers granted to the board superseded those of the Executive Council" but notes that "Aberhart was permitted to carry on with regular government operations."Byrne 172 Elliott and Miller take a similar approach to MacPherson's, suggesting that "Aberhart and his cabinet ... were in a position, strange in a cabinet system of government, of being ruled in the matter of economic policy by a board of private members that would be under the influence of Social Credit 'experts'." Barr disagrees, arguing that the Board was "still under the control of cabinet" and pointing out that "the cabinet was left with the power", through its privileged position in introducing legislation, "to supplement or alter the provisions of the ''Alberta Social Credit Act''" under which terms the board was constituted.

The cabinet disavowed any ownership of the act that established the Board. Though it was a government bill, the Provincial Treasurer explained that he took no responsibility for it, as it was drawn up by a committee of insurgents "without the interference of the cabinet". Though some insurgents complained that the version of the bill introduced by the government was different than that drafted by the committee, MacLachlan insisted that there had been no material changes. The bill was passed April 13, and the legislature adjourned the following day.MacPherson 173

MacLachlan travelled to England to invite Douglas to become head of the expert commission. Douglas refused but provided two of the experts the Board was charged with finding: L. D. Byrne, who was appointed to do most of the substantive work of creating the program, and George Frederick Powell, who was in charge of the commission's public relations.Elliott 264 MLAs returned to their constituencies during the legislative break, making it difficult for the insurgents to organise. Aberhart addressed his supporters in his weekly radio address, encouraging people to tell their MLAs to support him or force an election. Aberhart's supporters followed his instructions causing arguments at meetings between the insurgents and the loyalists. Aberhart fired William Chant, a known Douglasite, from his cabinet after he refused to resign.Elliott 263 A petition calling for Aberhart's resignation circulated among backbenchers, and proved to be a plant by the cabinet to test MLAs' loyalty. Outwardly, however, the Social Crediters showed a united front as they awaited the promised experts; in the first recorded vote after the legislature reconvened June 7, all insurgents present voted with the government, though 13 were absent.

One of Powell's first actions on arriving in Edmonton was to prepare a "loyalty pledge" committing its signatories "to uphold the Social Credit Board and its technicians." Most Social Credit MLAs signed, and the six who did not wrote to Powell assuring him of their loyalty to Douglas's objectivesMacPherson 51 (though one, former Provincial Treasurer Cockroft, later left the Social Credit League and unsuccessfully sought re-election as an "Independent Progressive").Brennan 51

Soon after the bills were introduced, Social Credit MLAs were subjected to a new loyalty pledge, this one shifting the target of their loyalty from the Social Credit Board to the cabinet. Six MLAs—including former cabinet ministers Chant, Cockroft, and Ross—refused to sign, and were ejected from caucus.

In the fall, Aberhart re-introduced the three disallowed acts in altered form, along with two new acts.Byrne 124 The ''Bank Taxation Act'' increased provincial taxes on banks by 2,230%, while the '' Accurate News and Information Act'' gave the chairman of the Social Credit Board a number of powers over newspapers, including the right to compel them to publish "any statement ... which has for its object the correction or amplification of any statement relating to any policy or activity of the Government or Province" and to require them to supply the names of sources. It also authorized cabinet to prohibit the publication of any newspaper, any article by a given writer, or any article making use of a given source.Barr 109 Bowen

Soon after the bills were introduced, Social Credit MLAs were subjected to a new loyalty pledge, this one shifting the target of their loyalty from the Social Credit Board to the cabinet. Six MLAs—including former cabinet ministers Chant, Cockroft, and Ross—refused to sign, and were ejected from caucus.

In the fall, Aberhart re-introduced the three disallowed acts in altered form, along with two new acts.Byrne 124 The ''Bank Taxation Act'' increased provincial taxes on banks by 2,230%, while the '' Accurate News and Information Act'' gave the chairman of the Social Credit Board a number of powers over newspapers, including the right to compel them to publish "any statement ... which has for its object the correction or amplification of any statement relating to any policy or activity of the Government or Province" and to require them to supply the names of sources. It also authorized cabinet to prohibit the publication of any newspaper, any article by a given writer, or any article making use of a given source.Barr 109 Bowen

The 1937 Social Credit backbenchers' revolt took place from March to June 1937 in the Canadian

The 1937 Social Credit backbenchers' revolt took place from March to June 1937 in the Canadian province

A province is an administrative division within a country or sovereign state, state. The term derives from the ancient Roman , which was the major territorial and administrative unit of the Roman Empire, Roman Empire's territorial possessions ou ...

of Alberta

Alberta is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province in Canada. It is a part of Western Canada and is one of the three Canadian Prairies, prairie provinces. Alberta is bordered by British Columbia to its west, Saskatchewan to its east, t ...

. It was a rebellion against Premier William Aberhart

William Aberhart (December 30, 1878 – May 23, 1943), also known as "Bible Bill" for his radio sermons about the Bible, was a Canadian politician and the seventh premier of Alberta from 1935 to his death in 1943. He was the founder and first le ...

by a group of backbench

In Westminster and other parliamentary systems, a backbencher is a member of parliament (MP) or a legislator who occupies no governmental office and is not a frontbench spokesperson in the Opposition, being instead simply a member of t ...

(not part of the cabinet) members of the Legislative Assembly (MLAs

A Member of the Legislative Assembly (MLA) is a representative elected to sit in a legislative assembly. The term most commonly refers to members of the legislature of a federated state or an autonomous region, but is also used for several nationa ...

) from his Social Credit League. The dissidents were unhappy with Aberhart's failure to provide Albertans with monthly dividends through social credit

Social credit is a distributive philosophy of political economy developed in the 1920s and 1930s by C. H. Douglas. Douglas attributed economic downturns to discrepancies between the cost of goods and the compensation of the workers who made t ...

as he had promised before his 1935 election. When the government's 1937 budget made no move to implement the dividends, many MLAs revolted openly and threatened to defeat the government in a confidence vote

A motion or vote of no confidence (or the inverse, a motion or vote of confidence) is a motion and corresponding vote thereon in a deliberative assembly (usually a legislative body) as to whether an officer (typically an executive) is deemed fit ...

.

The revolt took place in a period of turmoil for Aberhart and his government: besides the dissident backbenchers, half of the cabinet resigned or was fired over a period of less than a year. Aberhart also faced criticism for planning to attend the coronation of George VI at the province's expense and for stifling a recall

Recall may refer to:

* Recall (baseball), a baseball term

* Recall (bugle call), a signal to stop

* Recall (information retrieval), a statistical measure

* ReCALL (journal), ''ReCALL'' (journal), an academic journal about computer-assisted langua ...

attempt against him by the voters of his constituency.

After a stormy debate in which the survival of the government was called into question, a compromise was reached whereby Aberhart's government relinquished considerable power to a committee of backbenchers. This committee, dominated by insurgents, recruited two British social credit experts to come to Alberta and advise on the implementation of social credit. Among the experts' first moves was to require a loyalty pledge from Social Credit MLAs. Almost all signed, thus ending the crisis, though most of the legislation the experts proposed was ultimately disallowed or struck down as unconstitutional.

Background

During the

During the Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

, Calgary

Calgary () is a major city in the Canadian province of Alberta. As of 2021, the city proper had a population of 1,306,784 and a metropolitan population of 1,481,806 making it the third-largest city and fifth-largest metropolitan area in C ...

schoolteacher and radio evangelist William Aberhart converted to a British economic theory called social credit

Social credit is a distributive philosophy of political economy developed in the 1920s and 1930s by C. H. Douglas. Douglas attributed economic downturns to discrepancies between the cost of goods and the compensation of the workers who made t ...

. He promoted the theory in Alberta, believing it could end the depression and restore prosperity to the province. When the provincial government resisted its adoption, Aberhart organised social credit candidates for the 1935 provincial election. These candidates won 56 of the province's 63 seats, and Aberhart became Premier of Alberta

The premier of Alberta is the head of government and first minister of the Canadian province of Alberta. The current premier is Danielle Smith, leader of the governing United Conservative Party, who was sworn in on October 11, 2022.

The premi ...

.

In the runup to the campaign, Aberhart promised to increase Albertans' purchasing power

Purchasing power refers to the amount of products and services available for purchase with a certain currency unit. For example, if you took one unit of cash to a store in the 1950s, you could buy more products than you could now, showing that th ...

by providing monthly dividends to all citizens in the form of non-negotiable "credit certificates". While he did not commit to any specific dividend amount, he cited $20 and, later, $25 per month as reasonable figures. Though he noted that these figures were given "only for illustrative purposes", he repeated them so often that, in the assessment of his biographers David Elliott and Iris Miller, "it would have been impossible for any regular listener not to have gained the impression that Aberhart was promising him $25 a month if Social Credit should come to power."

Aberhart was not concerned about fulfilling campaign promises once elected, stating a week after the election that he thought the majority of his voters supported his initiatives for an uncorrupted government. He focused on reforming the provincial political institutions instead of enacting social credit policies. By the end of 1936, Aberhart's government had made no progress towards the promised dividends, leaving many Albertans disillusioned and frustrated. Aberhart's Social Credit MLAs, who had been elected on the promise of dividends, were angry at Aberhart's failure to follow through. Some felt that Aberhart lacked a real understanding of Douglas's theory and could not implement it. These MLAs wanted Douglas or somebody from his British organization to come to Alberta and fulfil Aberhart's campaign promises.Elliott 251 One such MLA, Samuel Barnes, had been expelled from the Social Credit caucus

A caucus is a group or meeting of supporters or members of a specific political party or movement. The exact definition varies between different countries and political cultures.

The term originated in the United States, where it can refer to ...

and from the Social Credit League for voicing these views.

Genesis

In December 1936, John Hargrave, the leader of the Social Credit Party of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, visited Alberta. While he had been disowned by Douglas, many MLAs frustrated with Aberhart hoped he would help implement social credit policies in the province. Hargrave met with Aberhart and his cabinet, who told him that theCanadian constitution

The Constitution of Canada () is the supreme law in Canada. It outlines Canada's system of government and the civil and human rights of those who are citizens of Canada and non-citizens in Canada. Its contents are an amalgamation of various ...

(which made banking a matter of federal, rather than provincial, jurisdiction) was an obstacle to introducing social credit. Hargrave proposed a plan for implementing social credit in Alberta; while he acknowledged that it was unconstitutional, he believed that the federal government would not dare enforce its jurisdiction in the face of broad popular support for the program. After presenting his plan to a group of Social Credit MLAs, the news media reported that Aberhart intended to implement radical and unconstitutional laws. Aberhart disavowed implementing unconstitutional policies and announced that neither he nor his cabinet supported Hargrave's plan.Elliott 253

Despite this statement, the Social Credit caucus invited Hargrave to explain his plan, which he did to the approval of many caucus members. Attorney-General John Hugill pointed out that the plan was unconstitutional, to which Hargrave replied that he was "not interested in legal arguments." Two weeks later, Hargrave left the province, telling the press that he "found it impossible to co-operate with a government which e considereda mere vacillating machine."Elliott 255 In this message, some MLAs found confirmation of their misgivings about Aberhart. A group of them, reported as numbering anywhere from five ("soon joined by eight or ten others") to 22,Brennan 48Barr 102 or 30Schultz 5 held meetings in

Despite this statement, the Social Credit caucus invited Hargrave to explain his plan, which he did to the approval of many caucus members. Attorney-General John Hugill pointed out that the plan was unconstitutional, to which Hargrave replied that he was "not interested in legal arguments." Two weeks later, Hargrave left the province, telling the press that he "found it impossible to co-operate with a government which e considereda mere vacillating machine."Elliott 255 In this message, some MLAs found confirmation of their misgivings about Aberhart. A group of them, reported as numbering anywhere from five ("soon joined by eight or ten others") to 22,Brennan 48Barr 102 or 30Schultz 5 held meetings in Edmonton

Edmonton is the capital city of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Alberta. It is situated on the North Saskatchewan River and is the centre of the Edmonton Metropolitan Region, which is surrounded by Central Alberta ...

's Corona Hotel to discuss government policy and strategise their next political actions. Author Brian Brennan identifies their leader as Pembina MLA Harry Knowlton Brown, while the academic T. C. Byrne names Ronald Ansley, Joseph Unwin, and Albert Blue.Byrne 120

Minister of Lands and Mines Charles Cathmer Ross resigned late in 1936, followed by Provincial Treasurer Charles Cockroft on January 29, 1937. Neither minister's resignation was directly related to the dissidents' complaints, but the resignations were the public's first clue of dissent in Social Credit's ranks. Cockroft's resignation was followed by his deputy, J. F. Perceval, and there were rumours that Hugill and Minister of Agriculture and Trade and Industry William Chant would also resign.Barr 101 This left Minister of Health Wallace Warren Cross, Minister of Public Works and Railways and Telephones William Fallow, and Provincial Secretary Ernest Manning

Ernest Charles Manning (September 20, 1908 – February 19, 1996) was a Canadian politician and the eighth premier of Alberta between 1943 and 1968 for the Social Credit Party of Alberta. He served longer than any other premier in the province' ...

as Aberhart's only indisputably loyal ministers, and Manning was ill with tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB), also known colloquially as the "white death", or historically as consumption, is a contagious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can al ...

and away from the legislature. On February 19, William Carlos Ives of the Supreme Court of Alberta struck down a key provincial legislation, including an act that reduced the interest paid on the province's bonds by half (though this was only a technical defeat, since the government had been defaulting on its bond payments since the previous April).

On February 25, a new session of the legislature opened with the speech from the throne

A speech from the throne, or throne speech, is an event in certain monarchies in which the reigning sovereign, or their representative, reads a prepared speech to members of the nation's legislature when a Legislative session, session is opened. ...

. Its commitment to social credit was limited to a vaguely worded promise to pursue "a new economic order when social credit becomes effective."Brennan 49 Three days later, on his weekly radio program, Aberhart acknowledged that he had been unable to implement the monthly dividends during the eighteen-month period he had set as his deadline, and asked Social Credit constituency association

An electoral district association (), commonly known as a riding association () or constituency association, is the basic unit of a political party at the level of the electoral district (" riding") in Canadian politics. Major political parties a ...

presidents to convene meetings of all Social Credit members to decide whether he ought to resign. He suggested that, in light of poor spring road conditions in rural areas, these meetings be delayed until early June, during which time he would remain in office.

Open dissent

The media objected to Aberhart's plan to place his government's future in the hands of the 10% of Albertans who were Social Credit members; the ''Calgary Herald

The ''Calgary Herald'' is a daily newspaper published in Calgary, Alberta, Canada. Publication began in 1883 as ''The Calgary Herald, Mining and Ranche Advocate, and General Advertiser''. It is owned by the Postmedia Network.

History

''The C ...

'' called for an immediate election. To many Social Credit MLAs, Aberhart's greater offense was bypassing them, the people's elected representatives. This was especially irksome in view of social credit's political philosophy, which favoured technocratic

Technocracy is a form of government in which decision-makers appoint knowledge experts in specific domains to provide them with advice and guidance in various areas of their policy-making responsibilities. Technocracy follows largely in the tra ...

rule and held that elected representatives' only legitimate function was channelling the public desire; by appealing directly to Social Credit members, Aberhart appeared to be denying the MLAs this role.MacPherson 170 In the legislature, Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civiliza ...

leader David Duggan called for Aberhart's resignation; in a move that Brennan reports shocked the assembly, his call was endorsed by Social Credit backbencher Albert Blue.

On March 11 or 12,Elliott 257 Cockroft's replacement as Provincial Treasurer, Solon Low, introduced the government's budget. It included no implementation of social credit, and was attacked by the opposition parties as "the default budget" and by insurgent Social Crediters as a "banker's budget" (a harsh insult given Social Credit's dim view of the banking industry). Ronald Ansley, a Social Credit MLA, attacked it as containing "not one single item that even remotely resembled Social Credit." Blue, again echoing Duggan, threatened on March 16 to vote against the government's interim supply bill

In the Westminster system (and, colloquially, in the United States), a money bill or supply bill is a bill that solely concerns taxation or government spending (also known as appropriation of money), as opposed to changes in public law.

Conv ...

, the defeat of which, under the conventions of the Westminster parliamentary system

The Westminster system, or Westminster model, is a type of parliamentary government that incorporates a series of procedures for operating a legislature, first developed in England. Key aspects of the system include an executive branch made up ...

, would force the government's resignation. In response, Aberhart praised Blue's courage in speaking his mind, and called him a worthy Social Crediter.Elliott 258

Surprised by Aberhart's refusal to be involved in open conflict, the insurgents needed time to reassess their strategy. On March 17, Lieutenant-Governor Primrose died, necessitating a five-day adjournment of the legislature while the federal government selected a replacement. When the legislature reconvened on March 22Elliott 259 or 23, the dissidents

Surprised by Aberhart's refusal to be involved in open conflict, the insurgents needed time to reassess their strategy. On March 17, Lieutenant-Governor Primrose died, necessitating a five-day adjournment of the legislature while the federal government selected a replacement. When the legislature reconvened on March 22Elliott 259 or 23, the dissidents filibuster

A filibuster is a political procedure in which one or more members of a legislative body prolong debate on proposed legislation so as to delay or entirely prevent a decision. It is sometimes referred to as "talking a bill to death" or "talking ...

ed against the budget. On March 24, Harry Knowlton Brown moved an adjournment, which was carried over the government's objections by a vote of 27 to 25. Though the insurgents considered this a vote of non-confidence

A motion or vote of no confidence (or the inverse, a motion or vote of confidence) is a motion and corresponding vote thereon in a deliberative assembly (usually a legislative body) as to whether an officer (typically an executive) is deemed fit ...

in Aberhart's government, he refused to resign; he acknowledged, however, that he would do so if the budget itself was defeated.Brennan 50

Coronation and recall petition

Though the bulk of the revolt took place in and around the legislature over the issue of social credit and government fiscal policy, Aberhart was also under attack on other fronts. He planned to attend thecoronation of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth

The coronation of the British monarch, coronation of George VI and his wife, Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother, Elizabeth, as King of the United Kingdom, king and List of British royal consorts, queen of the United Kingdom and Commonwealth realm, ...

, set for May 1937 in London. In the same speech in which he threatened to bring down the government on the supply motion, Blue attacked the trip as an extravagance that depression-ridden Alberta could ill afford. Faced with a political insurgency at home, Aberhart reluctantly decided at the end of March to cancel his trip, inaccurately claiming that he had never definitely decided to go.Elliott 261

In their first legislative act in 1935, the Social Credit government implemented the possibility of recall election

A recall election (also called a recall referendum, recall petition or representative recall) is a procedure by which voters can remove an elected official from office through a referendum before that official's term of office has ended. Recalls ...

s for MLAs.Elliott 273 As Aberhart's popularity fell, the residents of his Okotoks-High River

Okotoks-High River was a provincial electoral district in Alberta, Canada, mandated to return a single member to the Legislative Assembly of Alberta from 1930 to 1971.

History

The Okotoks—High River electoral district was formed prior to th ...

riding began a petition for his recall. On April 9 their petition was endorsed by the riding's Social Credit constituency association,Barr 105 and by fall it had gathered the signatures of the required two-thirds of the electorate. In response, the Social Crediters repealed the ''Recall Act'' retroactive to its date of origin; Aberhart claimed that oil companies active in his riding had intimidated their workers into signing the petition, and that some of the signatories had moved to the area specifically to sign.

Manoeuvring and negotiation

In the aftermath of the insurgent victory on Brown's adjournment motion, Aberhart gave notice of closure on the budget debate on March 29, the first time a premier in Canada used this rule against members of their own party. Aberhart belatedly realized that a defeat on this vote might force his resignations as premier. He then announced that he would seek the consent of the legislature to withdraw his closure motion and move an interim supply motion instead. The unanimous consent needed to withdraw the closure motion was refused, and the motion itself was defeated. That evening, Aberhart negotiated with the insurgents for four hours until a compromise was accepted: the insurgents would support the supply bill, in exchange for which the cabinet would introduce a bill amending the ''Social Credit Measures Act'' to establish a board of MLAs empowered to appoint a commission of five experts to implement social credit.Elliott 260 On March 31 the insurgents kept their part of the agreement by allowing the supply bill to be passed on second reading, thus allowing further debate on the bill to continue, and for the budget to be hoisted (postponed) for ninety days.Barr 103 When the cabinet introduced its promised bill, the insurgents claimed that it was not as agreed and refused to support it. They demanded Aberhart's resignation and announced that they were prepared to take over the government within 24 hours. A delegation put this demand to Aberhart in the evening of March 31; according to them, he agreed to resign if they allowed the supply bill to pass a third reading, which would almost guarantee the passage of the bill into law. They did so, but Aberhart denied that he had agreed to resign and refused to do so unless he was defeated in a general election. The Social Credit caucus met that evening to consider calling an election or removing Aberhart as premier.Shultz 12–13 The insurgents, leery of Aberhart's oratorical powers and the reach of his weekly radio show, wanted to avoid an election.Elliott 261 The insurgents did not have enough support to remove Aberhart as premier, so the caucus notified the premier that they had not reached a decision and the status quo remained. On April 8MacPherson 171 or 12, the government capitulated. Low's ''Alberta Social Credit Act'' delivered what the insurgents wanted, including the creation of "Alberta credit" in the amount of "the unused capacity of industries and people of Alberta to produce wanted goods and services", the establishment of "credit houses" to distribute this credit, and the creation of a Social Credit Board. The bill was passed, and the insurgents were placated, though Brown warned during a cross-province speaking tour that they were determined to see social credit implemented, and "if anyone gets in our way, he's going to get into trouble ... we must choose between principles and party, between Social Credit and Premier Aberhart."Barr 104Social Credit Board and commission

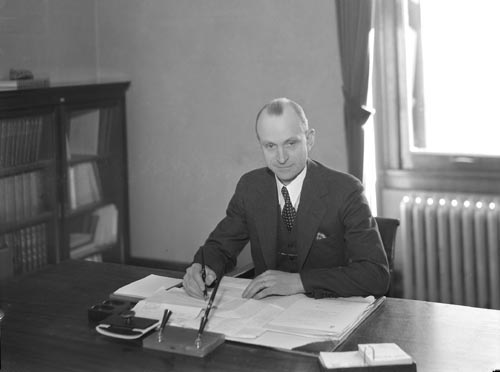

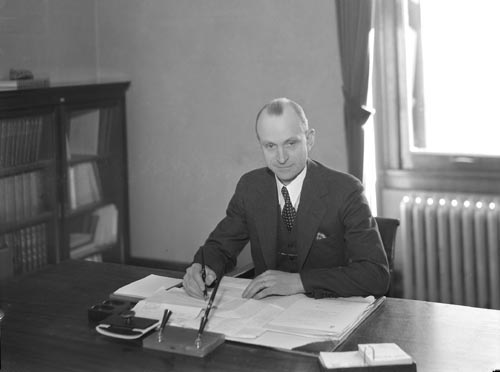

The Social Credit Board comprised five backbenchers. Insurgent Glenville MacLachlan was chair, and Aberhart loyalist Floyd Baker was secretary. The other three members were insurgents Selmer Berg, James L. McPherson, and William E. Hayes. The Board was empowered to appoint a commission of between three and five experts to implement social credit; the commission was to be responsible to the Board.MacPherson 172 Historians have taken different approaches to analyzing the effect of the Board on traditional Westminster parliamentary governance. Political scientist C. B. MacPherson emphasized "the extent to which the cabinet had abdicated in favour of a board composed of a few private members of the legislature", Byrne agrees that "in some respects, the powers granted to the board superseded those of the Executive Council" but notes that "Aberhart was permitted to carry on with regular government operations."Byrne 172 Elliott and Miller take a similar approach to MacPherson's, suggesting that "Aberhart and his cabinet ... were in a position, strange in a cabinet system of government, of being ruled in the matter of economic policy by a board of private members that would be under the influence of Social Credit 'experts'." Barr disagrees, arguing that the Board was "still under the control of cabinet" and pointing out that "the cabinet was left with the power", through its privileged position in introducing legislation, "to supplement or alter the provisions of the ''Alberta Social Credit Act''" under which terms the board was constituted.

The cabinet disavowed any ownership of the act that established the Board. Though it was a government bill, the Provincial Treasurer explained that he took no responsibility for it, as it was drawn up by a committee of insurgents "without the interference of the cabinet". Though some insurgents complained that the version of the bill introduced by the government was different than that drafted by the committee, MacLachlan insisted that there had been no material changes. The bill was passed April 13, and the legislature adjourned the following day.MacPherson 173

MacLachlan travelled to England to invite Douglas to become head of the expert commission. Douglas refused but provided two of the experts the Board was charged with finding: L. D. Byrne, who was appointed to do most of the substantive work of creating the program, and George Frederick Powell, who was in charge of the commission's public relations.Elliott 264 MLAs returned to their constituencies during the legislative break, making it difficult for the insurgents to organise. Aberhart addressed his supporters in his weekly radio address, encouraging people to tell their MLAs to support him or force an election. Aberhart's supporters followed his instructions causing arguments at meetings between the insurgents and the loyalists. Aberhart fired William Chant, a known Douglasite, from his cabinet after he refused to resign.Elliott 263 A petition calling for Aberhart's resignation circulated among backbenchers, and proved to be a plant by the cabinet to test MLAs' loyalty. Outwardly, however, the Social Crediters showed a united front as they awaited the promised experts; in the first recorded vote after the legislature reconvened June 7, all insurgents present voted with the government, though 13 were absent.

One of Powell's first actions on arriving in Edmonton was to prepare a "loyalty pledge" committing its signatories "to uphold the Social Credit Board and its technicians." Most Social Credit MLAs signed, and the six who did not wrote to Powell assuring him of their loyalty to Douglas's objectivesMacPherson 51 (though one, former Provincial Treasurer Cockroft, later left the Social Credit League and unsuccessfully sought re-election as an "Independent Progressive").Brennan 51

Historians have taken different approaches to analyzing the effect of the Board on traditional Westminster parliamentary governance. Political scientist C. B. MacPherson emphasized "the extent to which the cabinet had abdicated in favour of a board composed of a few private members of the legislature", Byrne agrees that "in some respects, the powers granted to the board superseded those of the Executive Council" but notes that "Aberhart was permitted to carry on with regular government operations."Byrne 172 Elliott and Miller take a similar approach to MacPherson's, suggesting that "Aberhart and his cabinet ... were in a position, strange in a cabinet system of government, of being ruled in the matter of economic policy by a board of private members that would be under the influence of Social Credit 'experts'." Barr disagrees, arguing that the Board was "still under the control of cabinet" and pointing out that "the cabinet was left with the power", through its privileged position in introducing legislation, "to supplement or alter the provisions of the ''Alberta Social Credit Act''" under which terms the board was constituted.

The cabinet disavowed any ownership of the act that established the Board. Though it was a government bill, the Provincial Treasurer explained that he took no responsibility for it, as it was drawn up by a committee of insurgents "without the interference of the cabinet". Though some insurgents complained that the version of the bill introduced by the government was different than that drafted by the committee, MacLachlan insisted that there had been no material changes. The bill was passed April 13, and the legislature adjourned the following day.MacPherson 173

MacLachlan travelled to England to invite Douglas to become head of the expert commission. Douglas refused but provided two of the experts the Board was charged with finding: L. D. Byrne, who was appointed to do most of the substantive work of creating the program, and George Frederick Powell, who was in charge of the commission's public relations.Elliott 264 MLAs returned to their constituencies during the legislative break, making it difficult for the insurgents to organise. Aberhart addressed his supporters in his weekly radio address, encouraging people to tell their MLAs to support him or force an election. Aberhart's supporters followed his instructions causing arguments at meetings between the insurgents and the loyalists. Aberhart fired William Chant, a known Douglasite, from his cabinet after he refused to resign.Elliott 263 A petition calling for Aberhart's resignation circulated among backbenchers, and proved to be a plant by the cabinet to test MLAs' loyalty. Outwardly, however, the Social Crediters showed a united front as they awaited the promised experts; in the first recorded vote after the legislature reconvened June 7, all insurgents present voted with the government, though 13 were absent.

One of Powell's first actions on arriving in Edmonton was to prepare a "loyalty pledge" committing its signatories "to uphold the Social Credit Board and its technicians." Most Social Credit MLAs signed, and the six who did not wrote to Powell assuring him of their loyalty to Douglas's objectivesMacPherson 51 (though one, former Provincial Treasurer Cockroft, later left the Social Credit League and unsuccessfully sought re-election as an "Independent Progressive").Brennan 51

Aftermath

Byrne and Powell prepared three acts for the implementation of social credit: the ''Credit of Alberta Regulation Act'', the ''Bank Employees Civil Rights Act'', and the ''Judicature Act Amendment Act''. The first required all bankers to obtain a license from the Social Credit Commission and created a directorate for the control of each bank, most members of which would be appointed by the Social Credit Board. The second prevented unlicensed banks and their employees from initiating civil actions. The third prevented any person from challenging the constitutionality of Alberta's laws in court without receiving the approval of the Lieutenant-Governor in Council. All three acts were quickly passed.MacPherson 177 New Lieutenant-Governor John C. Bowen, asked to grantroyal assent

Royal assent is the method by which a monarch formally approves an act of the legislature, either directly or through an official acting on the monarch's behalf. In some jurisdictions, royal assent is equivalent to promulgation, while in othe ...

, called Aberhart and Attorney-General Hugill to his office. He asked Hugill if, as a lawyer, he believed that the proposed laws were constitutional; Hugill replied that he did not. Aberhart said that he would take responsibility for the bills, which Bowen then signed. As they left the meeting, Aberhart asked Hugill for his resignation, which he received. Shortly after, the federal government disallowed all three acts.Elliott 268 Powell was not discouraged, stating that the acts "had been drawn up mainly to show the people of Alberta who were their ''real'' enemies, and in that respect they succeeded admirably."

Soon after the bills were introduced, Social Credit MLAs were subjected to a new loyalty pledge, this one shifting the target of their loyalty from the Social Credit Board to the cabinet. Six MLAs—including former cabinet ministers Chant, Cockroft, and Ross—refused to sign, and were ejected from caucus.

In the fall, Aberhart re-introduced the three disallowed acts in altered form, along with two new acts.Byrne 124 The ''Bank Taxation Act'' increased provincial taxes on banks by 2,230%, while the '' Accurate News and Information Act'' gave the chairman of the Social Credit Board a number of powers over newspapers, including the right to compel them to publish "any statement ... which has for its object the correction or amplification of any statement relating to any policy or activity of the Government or Province" and to require them to supply the names of sources. It also authorized cabinet to prohibit the publication of any newspaper, any article by a given writer, or any article making use of a given source.Barr 109 Bowen

Soon after the bills were introduced, Social Credit MLAs were subjected to a new loyalty pledge, this one shifting the target of their loyalty from the Social Credit Board to the cabinet. Six MLAs—including former cabinet ministers Chant, Cockroft, and Ross—refused to sign, and were ejected from caucus.

In the fall, Aberhart re-introduced the three disallowed acts in altered form, along with two new acts.Byrne 124 The ''Bank Taxation Act'' increased provincial taxes on banks by 2,230%, while the '' Accurate News and Information Act'' gave the chairman of the Social Credit Board a number of powers over newspapers, including the right to compel them to publish "any statement ... which has for its object the correction or amplification of any statement relating to any policy or activity of the Government or Province" and to require them to supply the names of sources. It also authorized cabinet to prohibit the publication of any newspaper, any article by a given writer, or any article making use of a given source.Barr 109 Bowen reserved

Reserved is a Polish apparel retailer headquartered in Gdańsk, Poland. It was founded in 1999 and remains the flagship brand of the LPP (company), LPP group, which has more than 2,200 retail stores located in over 38 countries and also owns su ...

approval of the bills until the Supreme Court of Canada

The Supreme Court of Canada (SCC; , ) is the highest court in the judicial system of Canada. It comprises nine justices, whose decisions are the ultimate application of Canadian law, and grants permission to between 40 and 75 litigants eac ...

could comment on them; all were ruled unconstitutional in ''Reference re Alberta Statutes

''Reference Re Alberta Statutes'', also known as the Alberta Press case and the Alberta Press Act Reference, is a landmark reference question, reference of the Supreme Court of Canada where several provincial laws, including one restricting the pr ...

''.

During the fall session in which the offending bills were proposed, police raided an Edmonton office of the Social Credit League and confiscated 4,000 copies of a pamphlet called "The Bankers' Toadies", which urged its readers as follows: "My child, you should NEVER say hard or unkind things about Bankers' Toadies. God made snakes, slugs, snails and other creepy-crawly, treacherous and poisonous things. NEVER, therefore, abuse them—just exterminate them!" The pamphlet also listed eight alleged toadies, including Conservative leader Duggan, former Attorney-General John Lymburn, and Senator

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or Legislative chamber, chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the Ancient Rome, ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior ...

William Antrobus Griesbach

Major general, Major General William Antrobus Griesbach, (January 3, 1878 – January 21, 1945) was a Canadian politician, decorated soldier, mayor of Edmonton, and member of the House of Commons of Canada, House of Commons and of the Senate ...

. Powell and Social Credit whip

A whip is a blunt weapon or implement used in a striking motion to create sound or pain. Whips can be used for flagellation against humans or animals to exert control through pain compliance or fear of pain, or be used as an audible cue thro ...

Joe Unwin were charged with criminal libel

Criminal libel is a legal term, of English origin, which may be used with one of two distinct meanings, in those common law jurisdictions where it is still used.

It is an alternative name for the common law offence which is also known (in order ...

and counsel to murder. Both were convicted of the former charge. Unwin was sentenced to three months hard labour; Powell was sentenced to six months and deported.

Aberhart's government was re-elected in the 1940 election with a reduced majority of 36 of 63 seats. Among the defeated incumbents were dissident leader Brown, the convicted Unwin, the expelled Barnes, and the Provincial Treasurer Low. Aberhart won re-election by running in Calgary

Calgary () is a major city in the Canadian province of Alberta. As of 2021, the city proper had a population of 1,306,784 and a metropolitan population of 1,481,806 making it the third-largest city and fifth-largest metropolitan area in C ...

; his replacement as Social Credit candidate in Okotoks–High River was soundly defeated. Though the disallowance of banking bills prevented the implementation of a social credit program, the Social Credit Board persisted until 1948, when it was dissolved in response to a number of its anti-semitic

Antisemitism or Jew-hatred is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Whether antisemitism is considered a form of racism depends on the school of thought. Antisemi ...

pronouncements and its suggestion that the secret ballot

The secret ballot, also known as the Australian ballot, is a voting method in which a voter's identity in an election or a referendum is anonymous. This forestalls attempts to influence the voter by intimidation, blackmailing, and potential vote ...

and political parties

A political party is an organization that coordinates candidates to compete in a particular area's elections. It is common for the members of a party to hold similar ideas about politics, and parties may promote specific ideological or p ...

be eliminated.Brennan 94–95

Notes

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:1937 Social Credit Backbenchers' Revolt Social Credit Backbenchers Revolt, 1937 Social Credit Backbenchers Revolt, 1937 Political history of Alberta Canadian social credit movement Alberta Social Credit Party Rebellions in Canada