ĘŋAbd-al-RaáļĨman Al-MahdÄŦ on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Since antiquity

Since antiquity

By 1891, after a prolonged struggle, the Kalifa

By 1891, after a prolonged struggle, the Kalifa

After the British took control, Abd al-Rahman lived at first with a relative in the Gezira. On the advice of the Inspector General Slatin Pasha, Abd al-Rahman was constantly watched in the early years of British rule, was given a very small allowance and was not allowed to call himself ''Imam'' or ''the Mahdi''. Both Slatin and the Governor-General

After the British took control, Abd al-Rahman lived at first with a relative in the Gezira. On the advice of the Inspector General Slatin Pasha, Abd al-Rahman was constantly watched in the early years of British rule, was given a very small allowance and was not allowed to call himself ''Imam'' or ''the Mahdi''. Both Slatin and the Governor-General

In 1919 Sayyid Abd al-Rahman al-Mahdi was among a delegation of Sudanese notables who went to London to congratulate King

In 1919 Sayyid Abd al-Rahman al-Mahdi was among a delegation of Sudanese notables who went to London to congratulate King

The British had ceded some power in Egypt with the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty of 1922 and more in the

The British had ceded some power in Egypt with the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty of 1922 and more in the

Sayyid Abd al-Rahman died on 24 March 1959, aged 73. Throughout a long and turbulent career he had always been a strong and consistent leader of the neo-Mahdist movement. By the end of the condominium in 1956, Abd al-Rahman was reported to be the wealthiest of all Sudanese. The British would have preferred the Ansar movement to be purely religious in nature, but Sayyid Abd al-Rahman al-Mahdi was also a competent political leader of Sudan. Explanations for the resurgence of neo-Mahdism in Sudan have included the British need for a figurehead, Abd al-Rahman's financial influence as his cotton growing business expanded, or a resurgence of religious and nationalist feeling in the Ansar sect.

Abd al-Rahman's son Sayyid al-Siddiq al-Mahdi was Imam of the Ansar for the next two years. After al-Siddiq's death in 1961 he was succeeded as imam by his brother Sayyid Imam al-Hadi al-Mahdi, al-Hadi al-Mahdi, while al-Siddiq's son Sadiq al-Mahdi took over the leadership of the Umma party. Sadiq Al-Mahdi was arrested in 1970, and for many years alternated between spells in prison in Sudan and periods of exile. In 1985, Sadiq al-Mahdi, who studied at Oxford and fought for democracy, was again elected president of the Umma party. In the 1986 elections he became Prime Minister of Sudan, holding office until the government was overthrown by a Muslim Brotherhood coup d'ÃĐtat in 1989. After further imprisonment and exile, Sadiq al-Mahdi returned to Sudan in 2000 and in 2002 was elected Imam of the Ansar. In 2003 Sadiq Al-Mahdi was re-elected President of Umma.

Sayyid Abd al-Rahman died on 24 March 1959, aged 73. Throughout a long and turbulent career he had always been a strong and consistent leader of the neo-Mahdist movement. By the end of the condominium in 1956, Abd al-Rahman was reported to be the wealthiest of all Sudanese. The British would have preferred the Ansar movement to be purely religious in nature, but Sayyid Abd al-Rahman al-Mahdi was also a competent political leader of Sudan. Explanations for the resurgence of neo-Mahdism in Sudan have included the British need for a figurehead, Abd al-Rahman's financial influence as his cotton growing business expanded, or a resurgence of religious and nationalist feeling in the Ansar sect.

Abd al-Rahman's son Sayyid al-Siddiq al-Mahdi was Imam of the Ansar for the next two years. After al-Siddiq's death in 1961 he was succeeded as imam by his brother Sayyid Imam al-Hadi al-Mahdi, al-Hadi al-Mahdi, while al-Siddiq's son Sadiq al-Mahdi took over the leadership of the Umma party. Sadiq Al-Mahdi was arrested in 1970, and for many years alternated between spells in prison in Sudan and periods of exile. In 1985, Sadiq al-Mahdi, who studied at Oxford and fought for democracy, was again elected president of the Umma party. In the 1986 elections he became Prime Minister of Sudan, holding office until the government was overthrown by a Muslim Brotherhood coup d'ÃĐtat in 1989. After further imprisonment and exile, Sadiq al-Mahdi returned to Sudan in 2000 and in 2002 was elected Imam of the Ansar. In 2003 Sadiq Al-Mahdi was re-elected President of Umma.

Sir

''Sir'' is a formal honorific address in English for men, derived from Sire in the High Middle Ages. Both are derived from the old French "" (Lord), brought to England by the French-speaking Normans, and which now exist in French only as part ...

Sayyid

''Sayyid'' is an honorific title of Hasanid and Husaynid lineage, recognized as descendants of the Islamic prophet Muhammad through his daughter Fatima and Ali's sons Hasan ibn Ali, Hasan and Husayn ibn Ali, Husayn. The title may also refer ...

Abdul Rahman al-Mahdi, KBE

KBE may refer to:

* Knight Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, post-nominal letters

* Knowledge-based engineering

Knowledge-based engineering (KBE) is the application of knowledge-based systems technology to the domain o ...

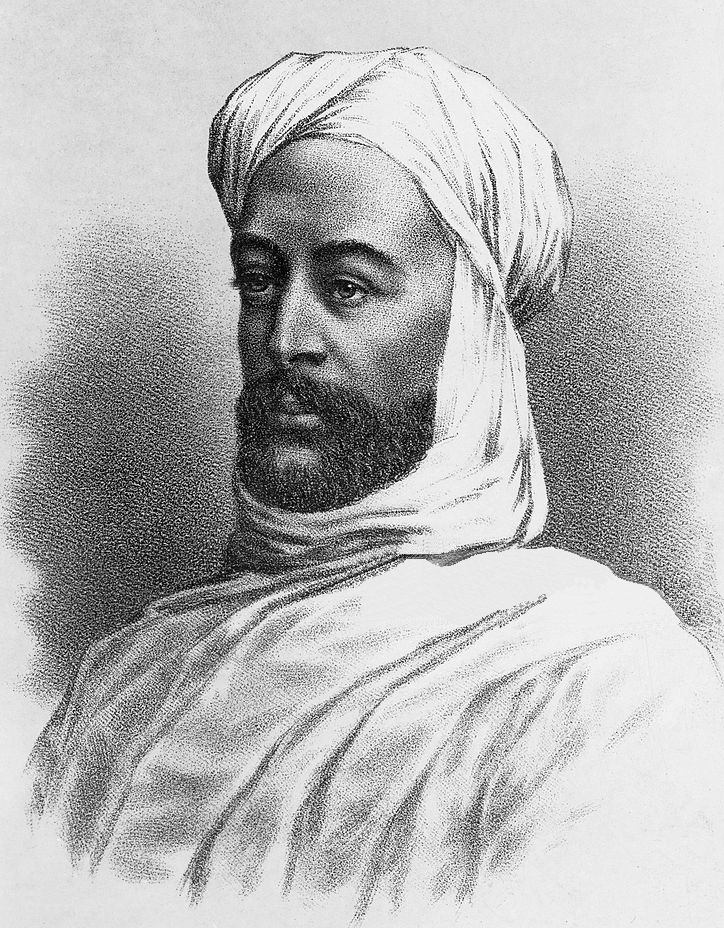

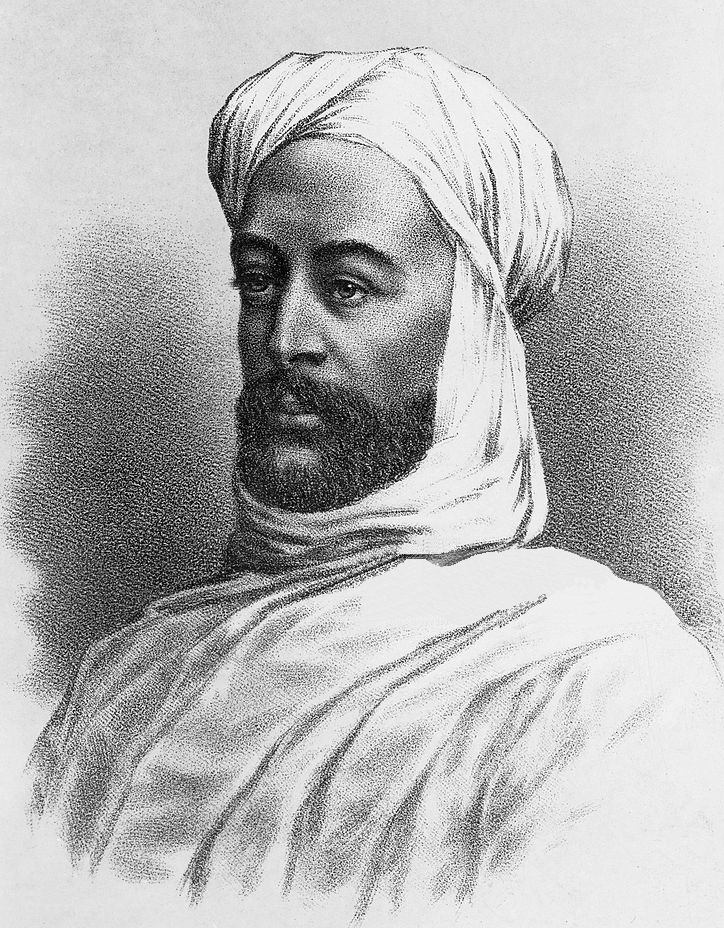

(; June 1885 â 24 March 1959) was a Sudanese politician and prominent religious leader. He was one of the leading religious and political figures during the colonial era in Anglo-Egyptian Sudan

Anglo-Egyptian Sudan ( ') was a condominium (international law), condominium of the United Kingdom and Kingdom of Egypt, Egypt between 1899 and 1956, corresponding mostly to the territory of present-day South Sudan and Sudan. Legally, sovereig ...

(1898â1955), and continued to exert great authority as leader of the Neo-Mahdists after Sudan

Sudan, officially the Republic of the Sudan, is a country in Northeast Africa. It borders the Central African Republic to the southwest, Chad to the west, Libya to the northwest, Egypt to the north, the Red Sea to the east, Eritrea and Ethiopi ...

became independent. The British tried to exploit his influence over the Sudanese people while at the same time profoundly distrusting his motives. Throughout most of the colonial era of Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, the British saw al-Mahdi as important as a moderate leader of the Mahdists.

He was the posthumous son of Muhammad Ahmad bin Abd Allah, who had proclaimed himself the Mahdi or redeemer of the Islamic faith in 1881, and died in 1885 a few months after his forces had captured Khartoum

Khartoum or Khartum is the capital city of Sudan as well as Khartoum State. With an estimated population of 7.1 million people, Greater Khartoum is the largest urban area in Sudan.

Khartoum is located at the confluence of the White Nile â flo ...

. A joint British and Egyptian force recaptured Sudan in 1898. At first, the British severely restricted al-Mahdi's movement and activity. However, he soon emerged as the ''Imam

Imam (; , '; : , ') is an Islamic leadership position. For Sunni Islam, Sunni Muslims, Imam is most commonly used as the title of a prayer leader of a mosque. In this context, imams may lead Salah, Islamic prayers, serve as community leaders, ...

'' (leader) of the Ansar religious sect, supporters of the Mahdist movement.

The British maintained a close political relationship with al-Mahdi. Meanwhile, he grew wealthy from cotton production, for which his supporters provided labour since he was a child exiled to Aba Island

Aba Island is an island on the White Nile to the south of Khartoum, Sudan. It is the original home of the Mahdi in Sudan and the spiritual base of the Umma Party.

History

Aba Island was the birthplace of the Mahdiyya, first declared on Ju ...

, and was influential and well loved among his people. The British administration distrusted him because they could not control him or use him to exert influence in Sudan.

In the 1930s, he spoke out against a treaty between Egypt and Britain that recognized Egyptian claims of sovereignty in Sudan, although no Sudanese had been consulted. He travelled to London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

to make his case. His Ansar followers became an influential faction in the General Congress established in 1938, and in the successor Advisory Council set up in 1944. al-Mahdi was patron of the nationalist Umma

Umma () in modern Dhi Qar Province in Iraq, was an ancient city in Sumer. There is some scholarly debate about the Sumerian and Akkadian names for this site. Traditionally, Umma was identified with Tell Jokha. More recently it has been sugges ...

(Nation) political party in the period before and just after Sudan became independent in 1956. In 1958, the Umma party won the most seats in the first parliamentary elections after independence. In November 1958, the Sudanese Army staged a coup, which al-Mahdi supported. He died on 24 March 1959, aged 73.

Background

Since antiquity

Since antiquity Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

has straddled the trade route between the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern ...

, Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula (, , or , , ) or Arabia, is a peninsula in West Asia, situated north-east of Africa on the Arabian plate. At , comparable in size to India, the Arabian Peninsula is the largest peninsula in the world.

Geographically, the ...

, India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

and countries to the east. With the opening of the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal (; , ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, Indo-Mediterranean, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia (and by extension, the Sinai Peninsula from the rest ...

in 1869 it gained huge strategic importance. In 1882 the British took effective control of Egypt in the Anglo-Egyptian War

The British conquest of Egypt, also known as the Anglo-Egyptian War (), occurred in 1882 between Egyptian and Sudanese forces under Ahmed âUrabi and the United Kingdom. It ended a nationalist uprising against the Khedive Tewfik Pasha. It ...

.

Northern and central Sudan had been nominally under Egyptian suzerainty since an Ottoman force had conquered and occupied the region in 1821. The primary motive was not territorial conquest but to secure a source of slaves to serve in the Egyptian army. The slaves, paid in lieu of taxes, were brought from the formerly inaccessible regions of southern Sudan. When the British explorer Samuel Baker

Sir Samuel White Baker (8 June 1821 â 30 December 1893) was an English explorer, officer, naturalist, big game hunter, engineer, writer and abolitionist. He also held the titles of Pasha and Major-General in the Ottoman Empire and Egypt ...

visited Khartoum

Khartoum or Khartum is the capital city of Sudan as well as Khartoum State. With an estimated population of 7.1 million people, Greater Khartoum is the largest urban area in Sudan.

Khartoum is located at the confluence of the White Nile â flo ...

in 1862, he found that everyone in the town was involved in the slave trade, including the Governor-General. The Egyptian and Nubian garrison lived on the land like an army of occupation. Bribery was the only way to get anything done. Torture and floggings were routine in the prisons. Baker said of Khartoum that "a more miserable and unhealthy place can hardly be imagined". He described the Governor-General Musa Pasha as combining "the worst of Oriental failings with the brutality of a wild animal".

In the 1870s, a Muslim cleric named Muhammad Ahmad

Muhammad Ahmad bin Abdullah bin Fahal (; 12 August 1843 – 21 June 1885) was a Sudanese religious and political leader. In 1881, he claimed to be the Mahdi and led a war against Egyptian rule in Sudan, which culminated in a remarkable vi ...

began to preach renewal of the faith and liberation of Sudan from the Egyptians. In 1881 he proclaimed himself the Mahdi

The Mahdi () is a figure in Islamic eschatology who is believed to appear at the Eschatology, End of Times to rid the world of evil and injustice. He is said to be a descendant of Muhammad in Islam, Muhammad, and will appear shortly before Jesu ...

, the promised redeemer of the Islamic world. The Mahdi's followers were named "'' Ansar''", or helpers, the name that was given to the citizens of Medina

Medina, officially al-Madinah al-Munawwarah (, ), also known as Taybah () and known in pre-Islamic times as Yathrib (), is the capital of Medina Province (Saudi Arabia), Medina Province in the Hejaz region of western Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, ...

who helped Muhammad

Muhammad (8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious and political leader and the founder of Islam. Muhammad in Islam, According to Islam, he was a prophet who was divinely inspired to preach and confirm the tawhid, monotheistic teachings of A ...

. The religious and political revolt gathered momentum, with the Egyptians steadily losing ground and the British showing little enthusiasm for a costly engagement in this remote region. By the end of 1883, the Ansar army had wiped out three Egyptian armies. A force under William Hicks was sent to suppress the revolt but was destroyed. When the governor of Darfur

Darfur ( ; ) is a region of western Sudan. ''DÄr'' is an Arabic word meaning "home f â the region was named Dardaju () while ruled by the Daju, who migrated from MeroÃŦ , and it was renamed Dartunjur () when the Tunjur ruled the area. ...

, Slatin Pasha, surrendered to the Mahdi almost all of the west of Sudan had come under the Mahdi's control.

Major-General Charles George Gordon

Major-general (United Kingdom), Major-General Charles George Gordon Companion of the Order of the Bath, CB (28 January 1833 â 26 January 1885), also known as Chinese Gordon, Gordon Pasha, Gordon of Khartoum and General Gordon , was a British ...

was given the job of evacuating the Egyptian garrison from Khartoum

Khartoum or Khartum is the capital city of Sudan as well as Khartoum State. With an estimated population of 7.1 million people, Greater Khartoum is the largest urban area in Sudan.

Khartoum is located at the confluence of the White Nile â flo ...

. He arrived on 18 February 1884. Gordon was reluctant to abandon the population of Khartoum to the forces of the Mahdi, and also felt that by evacuating the city he would open the way for the Mahdi to threaten Egypt. He bombarded the authorities in Cairo

Cairo ( ; , ) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Egypt and the Cairo Governorate, being home to more than 10 million people. It is also part of the List of urban agglomerations in Africa, largest urban agglomeration in Africa, L ...

with telegrams suggesting alternative courses, and delayed starting the evacuation. On 13 March 1884 the tribes north of Khartoum declared for the Mahdi, cutting the telegraph and blocking river traffic. Khartoum was besieged, falling on 25 January 1885 after a siege of 313 days. A relief column arrived two days after the city had fallen and Gordon had been killed. Despite a short-lived public outcry in Britain over Gordon's death, Britain took no further action in Sudan for several years.

Mahdiyah (1885â1898)

Muhammad Ahmad died of typhus a few months after his victory, leaving power to his three deputies, or ''Kalifas''. Abd al-Rahman was born on 15 July 1885 inOmdurman

Omdurman () is a major city in Sudan. It is the second most populous city in the country, located in the State of Khartoum. Omdurman lies on the west bank of the River Nile, opposite and northwest of the capital city of Khartoum. The city acts ...

, three weeks after his father's death. His mother was granddaughter of a former Sultan of Darfur

Darfur ( ; ) is a region of western Sudan. ''DÄr'' is an Arabic word meaning "home f â the region was named Dardaju () while ruled by the Daju, who migrated from MeroÃŦ , and it was renamed Dartunjur () when the Tunjur ruled the area. ...

, Mohammed al-Fadl. As a child, Abd al-Rahman's only formal education was that of a religious school where the pupils memorised the Quran

The Quran, also Romanization, romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a WaáļĨy, revelation directly from God in Islam, God (''Allah, AllÄh''). It is organized in 114 chapters (, ) which ...

. By the age of eleven he could recite the Quran.

Abdallahi ibn Muhammad

Abdullah ibn-Mohammed al-Khalifa or Abdullah al-Taashi or Abdallah al-Khalifa, also known as "The Caliph, Khalifa" (; 184625 November 1899) was a Sudanese Ansar (Sudan), Ansar ruler who was one of the principal followers of Muhammad Ahmad. Ahmad c ...

emerged as sole leader due to support from the nomadic Baggara Arabs

The BaggÄra ( "heifer herder"), also known as Chadian Arabs, are a Nomad, nomadic confederation of people of mixed Arabs, Arab and Arabization, Arabized Indigenous peoples of Africa, indigenous African ancestry, inhabiting a portion of the Sa ...

of the west. He proved to be an able and ruthless ruler of the Mahdiyah, the Mahdist state. At first the state was run on military lines as a Jihadist state. Later, a more conventional form of administration was introduced. The Kalifa consolidated his rule in Sudan, then invaded Ethiopia

Ethiopia, officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country located in the Horn of Africa region of East Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the north, Djibouti to the northeast, Somalia to the east, Ken ...

, killing Emperor

The word ''emperor'' (from , via ) can mean the male ruler of an empire. ''Empress'', the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife (empress consort), mother/grandmother (empress dowager/grand empress dowager), or a woman who rules ...

Yohannes IV

Yohannes IV ( Tigrinya: áŪáááĩ áŽá ''Rabaiy YÅáļĨÄnnes''; horse name Abba Bezbiz also known as KahÅsai; born ''Lij'' Kahssai Mercha; 11 July 1837 â 10 March 1889) was Emperor of Ethiopia from 1871 to his death in 1889 at the ...

in March 1889 and penetrating as far as Gondar

Gondar, also spelled Gonder (Amharic: ááá°á, ''Gonder'' or ''GondÃĪr''; formerly , ''GĘ·andar'' or ''GĘ·ender''), is a city and woreda in Ethiopia. Located in the North Gondar Zone of the Amhara Region, Gondar is north of Lake Tana on ...

. The same year, the Kalifa attacked Egypt at Tushki, but was defeated.

However, the state suffered from economic problems and internal opposition to the Khalifa, particularly from the Mahdi's family, and the Khalifa was forced to concentrate on consolidation. The British detected his weakness, and prepared an invasion motivated in part by a desire to avenge Gordon's death, and in part by a desire for raw cotton

Cotton (), first recorded in ancient India, is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective case, around the seeds of the cotton plants of the genus '' Gossypium'' in the mallow family Malvaceae. The fiber is almost pure ...

for their textile industry. A methodical invasion was launched in 1896 slowly moving south supported by a railway that the army built along its route. The force reached Berber

Berber or Berbers may refer to:

Ethnic group

* Berbers, an ethnic group native to Northern Africa

* Berber languages, a family of Afro-Asiatic languages

Places

* Berber, Sudan, a town on the Nile

People with the surname

* Ady Berber (1913â196 ...

in September 1897 and Atbara

Atbara (sometimes Atbarah) ( ĘŋAáđbarah) is a city located in River Nile State in northeastern Sudan.

Because of its links to the railway industry, Atbara is also known as the 'Railway City'.

Atbara's population was recorded as 134,586 dur ...

in April 1898. The British and Egyptian force led by General Kitchener defeated the Kalifa at the Battle of Omdurman

The Battle of Omdurman, also known as the Battle of Karary, was fought during the Anglo-Egyptian conquest of Sudan between a BritishâEgyptian expeditionary force commanded by British Commander-in-Chief (sirdar) major general Horatio Herbert ...

on 2 September 1898. The battle is known as the Battle of Karari to Mahdists.

In his book ''The River War

''The River War: An Historical Account of the Reconquest of the Soudan'' (1899), by Winston Churchill, is a history of the conquest of the Sudan between 1896 and 1899 by Anglo-Egyptian forces led by Lord Kitchener. He defeated the Sudanese D ...

'', Sir Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 â 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

, who was present at the Battle, summed up the result: "The River War is over. In its varied course, which extended over fourteen years and involved the untimely destruction of perhaps 300,000 lives, many extremes and contrasts have been displayed. There have been battles which were massacres, and others that were mere parades. There have been occasions of shocking cowardice and surprising heroism... of wisdom and incompetence. But the result is at length achieved and the flags of England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

and Egypt wave unchallenged over the valley of the Nile".

The British sent the Mahdi's family to al-Shakaba on the Blue Nile

The Blue Nile is a river originating at Lake Tana in Ethiopia. It travels for approximately through Ethiopia and Sudan. Along with the White Nile, it is one of the two major Tributary, tributaries of the Nile and supplies about 85.6% of the wa ...

in September 1898. The group included the Khalifa Muhammad Sharif

Mian Muhammad Sharif (Punjabi language, Punjabi, , 18 November 1919 â 19 October 2004) was a Pakistani businessman who is known as the co-founder of Ittefaq Group and founder of Sharif Group. from one of the biggest political parties of the ...

, the Mahdi's cousin and one of his chosen successors. In 1899 the government heard rumours that the family group was advocating a Mahdist revival and dispatched a military force to al-Shakaba. One account stated that the force attacked the family and followers, firing on them at random. Abd al-Rahman was badly wounded and his two elder brothers were killed. Another account said that Muhammad Sharif and the two elder sons of the Mahdi were arrested. There was a skirmish when an attempt was made to rescue them. Muhammad Sharif and the Mahdi's two sons were found guilty by a court martial trial and were shot.

Organised resistance to the British had ended by 1899, although sporadic fighting continued for a few more years. In theory the British ruled Anglo-Egyptian Sudan

Anglo-Egyptian Sudan ( ') was a condominium (international law), condominium of the United Kingdom and Kingdom of Egypt, Egypt between 1899 and 1956, corresponding mostly to the territory of present-day South Sudan and Sudan. Legally, sovereig ...

in partnership with Egypt through a condominium

A condominium (or condo for short) is an ownership regime in which a building (or group of buildings) is divided into multiple units that are either each separately owned, or owned in common with exclusive rights of occupation by individual own ...

. In practice, although Egypt bore most of the costs of the military conquest and occupation of Sudan, the British ran the country as they chose. The head of the military and the civil administration under the 19 January 1899 Condominium Agreement was a British-nominated Governor-General, who acted independently of the Cairo government.

Early period of British rule

After the British took control, Abd al-Rahman lived at first with a relative in the Gezira. On the advice of the Inspector General Slatin Pasha, Abd al-Rahman was constantly watched in the early years of British rule, was given a very small allowance and was not allowed to call himself ''Imam'' or ''the Mahdi''. Both Slatin and the Governor-General

After the British took control, Abd al-Rahman lived at first with a relative in the Gezira. On the advice of the Inspector General Slatin Pasha, Abd al-Rahman was constantly watched in the early years of British rule, was given a very small allowance and was not allowed to call himself ''Imam'' or ''the Mahdi''. Both Slatin and the Governor-General Reginald Wingate

General Sir Francis Reginald Wingate, 1st Baronet (25 June 1861 â 29 January 1953) was a British Army officer and colonial administrator in Egypt and the Sudan. He served as Governor-General of the Sudan (1899â1916) and High Commissioner in ...

were determined to stamp out Mahdism. Slatin had been held a prisoner of the Mahdists for eleven years. He placed many restrictions on the Mahdist leaders such as prohibiting them from reading the Mahdi's prayer book, from visiting "sacred" places associated with their movement other than the Mahdi's tomb

The Mahdi's tomb or ''qubba'' () is located in Omdurman, Sudan. It was the burial place of Muhammad Ahmad, the leader of an Islamic revolt against Turco-Egyptian Sudan in the late 19th century.

The Mahdist State was established in 1885 after t ...

, and from praying or making offerings at the tomb.

From 1906 Abd al-Rahman lived in Gezirat al-Fil, near Omdurman. He was subject to constant and obtrusive supervision by the intelligence department. However, after 1908 Abd al-Rahman was allowed to live in Omdurman and study under a distinguished Azharite

The Al-Azhar University ( ; , , ) is a public university in Cairo, Egypt. Associated with Al-Azhar Al-Sharif in Islamic Cairo, it is Egypt's oldest degree-granting university and is known as one of the most prestigious universities for Islamic ...

named Muhammad al-Badawi, where he gained some understanding of Islamic jurisprudence and the fundamentals of his religion, including the Hadith

Hadith is the Arabic word for a 'report' or an 'account f an event and refers to the Islamic oral tradition of anecdotes containing the purported words, actions, and the silent approvals of the Islamic prophet Muhammad or his immediate circle ...

(traditional stories about Muhammad). However, he was never able to become a well-educated and knowledgeable Islamic scholar as his father had been. The government lent him money to build the family mosque in Omdurman in 1908, and let him farm part of his father's land on Aba Island

Aba Island is an island on the White Nile to the south of Khartoum, Sudan. It is the original home of the Mahdi in Sudan and the spiritual base of the Umma Party.

History

Aba Island was the birthplace of the Mahdiyya, first declared on Ju ...

. He emphasised his peaceful intentions, convincing the colonialist government that his movement was not dangerous. A British official described him in 1909, when he was aged about twenty-four, as "an obsequious, sorry-looking youth in soiled clothes". In 1910 he made a public speech in which he supported the condominium administration of Anglo-Egyptian Sudan.

Abd al-Rahman quietly began to regroup the Ansar as a religious sect. Until 1914, he lived in seclusion in Omdurman or on Aba Island, closely watched by Slatin's intelligence agents. Despite the surveillance, he built considerable influence in the White Nile region. He often visited the many mosques in Omdurman to meet his followers with his face covered so he would not be recognized by government agents. He received many visitors who sought his blessing.

World War I

WhenWorld War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 â 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

broke out in 1914, the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

sided with Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

against Britain. Governor-General Wingate had to persuade the Sudanese people that the Ottoman Empire was no longer a truly Muslim state. Wingate was helped by Sudanese memories of the harsh former Turkish rule. Wingate described Britain as the true defender of Islam, and called the Turkish rulers a "Syndicate of Jews, financiers and low-born intriguers". The British and most of the northern Sudanese saw the Sayyids

''Sayyid'' is an honorific title of Hasanid and Husaynid lineage, recognized as descendants of the Islamic prophet Muhammad through his daughter Fatima and Ali's sons Hasan and Husayn. The title may also refer to the descendants of the fami ...

, the leaders of the main Islamic groups, as the natural spokesmen for the people. Wingate decided to enlist Sayyid Abd al-Rahman to support the British cause. Abd al-Rahman publicly declared his full support for the British and assisted in suppressing a rebellion in the Nuba Mountains in 1915.

In 1915 Abd al-Rahman made a series of tours and visits to parts of the country where Mahdism was still strong, particularly among the Baggara

The BaggÄra ( "heifer herder"), also known as Chadian Arabs, are a nomadic confederation of people of mixed Arab and Arabized indigenous African ancestry, inhabiting a portion of the Sahel mainly between Lake Chad and the Nile river near sou ...

of the White Nile region, speaking in opposition to the Ottoman sultan's calls for Jihad

''Jihad'' (; ) is an Arabic word that means "exerting", "striving", or "struggling", particularly with a praiseworthy aim. In an Islamic context, it encompasses almost any effort to make personal and social life conform with God in Islam, God ...

. When he toured Aba Island in 1915, he was greeted by thousands of sword-carrying Mahdists who prayed that "the day had arrived". Alarmed at the possibility of a Mahdist revival, the British ordered him to return to Omdurman in 1916. However, Abd al-Rahman appointed agents in the Blue Nile and Funj provinces and later in Kordofan and Darfur. Their ostensible role was to report on any illegal activity and to encourage payment of taxes to the British. They took advantage of their visits to collect payments of ''zakat'' to Abd al-Rahman and to encourage the Ansar, who now freely used the illegal Mahdist prayer book, ''ratib al-mahdi''.

The British encouraged the development of a version of the Ansar movement that was not fanatical, and did much to accommodate Abd al-Rahman's ambitions, although they could not go as far as supporting his goal of becoming King of Sudan. However, the toleration and even support of Mahdism during World War I was not based on official policy. A British official who was critical of the support given to Abd al-Rahman at this time later wrote that some changes were "a modification of policy deliberately proposed; others ... the unforeseen consequence

In the social sciences, unintended consequences (sometimes unanticipated consequences or unforeseen consequences, more colloquially called knock-on effects) are outcomes of a purposeful action that are not intended or foreseen. The term was po ...

of action taken; others, perhaps the majority, appear superficially to represent a gradual drift, of which the Government was at the time unconscious".

Post World War I

In 1919 Sayyid Abd al-Rahman al-Mahdi was among a delegation of Sudanese notables who went to London to congratulate King

In 1919 Sayyid Abd al-Rahman al-Mahdi was among a delegation of Sudanese notables who went to London to congratulate King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 â 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until Death and state funeral of George V, his death in 1936.

George w ...

of the United Kingdom on the British victory in the war. In a dramatic gesture of loyalty, Abd al-Rahman presented the Mahdi's sword to the King. The delegation was led by Sayyid Ali al-Mirghani

Sir Sayyid Ali al-Mirghani (, 1873 â 21 February 1968) was a Sudanese religious and political leader. The late leader of the Khatmiyya, a Sufism, sufi order known in Egypt, Sudan and Eritrea. His family, settled in Kassala and Suakin, were hos ...

, the leader of the Khatmiyya

The Khatmiyya is a Sufi order or brotherhood (tariqa) founded by Sayyid Mohammed Uthman al-Mirghani al-Khatim.

The Khatmiyya is the largest Sufi order in Sudan, Eritrea and Ethiopia. It also has followers in Egypt, Chad, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, U ...

movement, who was later to clash with Abd al-Rahman over several issues.

After the war, the Ottoman Empire was broken up, leading to a revival of Egyptian nationalism. Some Egyptians claimed that Sudan was a natural extension of Egypt. The Sudanese view was mixed, with some wanting ties with Egypt to offset British influence and others wanting complete independence of Sudan.

In the post-war period, the Mahdi's family became wealthy from cotton production based on irrigation and migrant labourers, mainly their Baggara

The BaggÄra ( "heifer herder"), also known as Chadian Arabs, are a nomadic confederation of people of mixed Arab and Arabized indigenous African ancestry, inhabiting a portion of the Sahel mainly between Lake Chad and the Nile river near sou ...

followers from Darfur and Kordofan. These western tribes had been the backbone of the original Mahdist movement. The riverine tribes were more inclined to side with the rival Khatmiyya movement. The government supported Abd al-Rahman in these commercial enterprises. Abd al-Rahman's economic activity, and the resulting wide range of contacts with merchants and owners of pump-schemes for irrigating cotton fields, gave him influence among Sudanese engaged in commerce. From 1 January 1922, the government suspended payment of allowances to Mahdist notables other than the old and those whose movements were restricted. The allowance paid to Abd al-Rahman was increased somewhat, but only so that he could support old women and other vulnerable people whose allowances had been stopped.

By the 1920s, Abd al-Rahman was a respected religious and political leader. In 1921, he held a meeting at his home where the attendees signed two documents that laid out the Mahdist objectives. These were for Sudan to be ruled by Britain rather than Egypt, and for Sudan to eventually achieve self-government. In the early 1920s, between 5,000 and 15,000 pilgrims were coming to Aba Island each year to celebrate Ramadan

Ramadan is the ninth month of the Islamic calendar. It is observed by Muslims worldwide as a month of fasting (''Fasting in Islam, sawm''), communal prayer (salah), reflection, and community. It is also the month in which the Quran is believed ...

. Many of them identified Abd al-Rahman with '' Isa'', the Islamic interpretation of Jesus, and assumed that he would drive the Christian colonists out of Sudan. The British found that Abd al-Rahman was in correspondence with agents and leaders in Nigeria

Nigeria, officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf of Guinea in the Atlantic Ocean to the south. It covers an area of . With Demographics of Nigeria, ...

and Cameroon

Cameroon, officially the Republic of Cameroon, is a country in Central Africa. It shares boundaries with Nigeria to the west and north, Chad to the northeast, the Central African Republic to the east, and Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, and the R ...

, predicting the eventual victory of the Mahdists over the Christians. They blamed him for unrest in these colonies. After pilgrims from West Africa

West Africa, also known as Western Africa, is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations geoscheme for Africa#Western Africa, United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Gha ...

held mass demonstrations on Aba Island in 1924, Abd al-Rahman was told to put a stop to the pilgrimages.

For a long time the British were ambivalent in their attitude to Abd al-Rahman. He had provided valuable political assistance during World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 â 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

and in 1924. On the other hand, the Government of Sudan found that his services had a hidden agenda and described his actions as "evasive and obstructive". On balance the British found it best to treat Abd al-Rahman as an ally, although some felt that Governor-General Reginald Wingate

General Sir Francis Reginald Wingate, 1st Baronet (25 June 1861 â 29 January 1953) was a British Army officer and colonial administrator in Egypt and the Sudan. He served as Governor-General of the Sudan (1899â1916) and High Commissioner in ...

(1900â1918) was too lenient towards him. In September 1924 Sayyid Ali al-Mirghani, leader of the Khatmiyya

The Khatmiyya is a Sufi order or brotherhood (tariqa) founded by Sayyid Mohammed Uthman al-Mirghani al-Khatim.

The Khatmiyya is the largest Sufi order in Sudan, Eritrea and Ethiopia. It also has followers in Egypt, Chad, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, U ...

movement and Abd al-Rahman's rival, said he would prefer Sudan to be part of the Egyptian kingdom than to be an independent monarchy under Sayyid Abd al-Rahman. At that time the British favoured Sayyid Ali, who they saw as a purely religious leader, while they regarded Abd al-Rahman as having potentially dangerous political ambitions.

Political crises

In 1924, there was a crisis in Egypt when a government hostile to the British was elected. On 19 November 1924, the Governor of Sudan Sir Lee Stack was assassinated while driving through Cairo. The British responded with anger, demanding from the Egyptian government a public apology, an inquiry, suppression of demonstrations and the payment of a large fine. Further, they demanded withdrawal of all Egyptian officers and Egyptian army units from Sudan, an increase to the scope of an irrigation scheme in Gezira and laws to protect foreign investors in Egypt. Egyptian army units in Sudan, bound by their oath to the Egyptian king, refused to obey the orders of their British officers and mutinied. The British violently suppressed the mutiny, removed the Egyptian army from Sudan and purged the administration of Egyptian officials. The "condominium" remained legally in force, as it would until Sudan gained independence, but in practice Egypt now had no say in the administration of Sudan. In the aftermath of the upheaval the British saw educated Sudanese as potential propagators of "dangerous" nationalist ideas imported from Egypt. Although Abd al-Rahman had backed the government and condemned local supporters of the Egyptians, he was viewed with suspicion as a potential enemy of the colonial power. However, at the start of 1926, Abd al-Rahman made aKnight Commander of the Order of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding valuable service in a wide range of useful activities. It comprises five classes of awards across both civil and military divisions, the most senior two o ...

(KBE).

Sir Geoffrey Archer was appointed Governor-General of Sudan in 1925 in place of Sir Lee Stack. One of his early decisions was to initiate the formation of the Sudan Defence Force

The Sudan Defence Force (SDF) was a British Colonial Auxiliary Forces unit raised in the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan in 1925 to assist local police in internal security duties and maintain the condominium's territorial integrity. During World War II, ...

, with a command completely separate from the Egyptian army. He dropped the Egyptian title "Sirdar" for the supreme commander, and did not wear the Egyptian tarboush. He made it very clear that he was commander in chief of a purely Sudanese army, while reassuring Sudanese officers who had served in the Egyptian army that they would be retained if they had not taken part in the mutiny. The British authorities, who had again became hostile to Mahdism, banned the enlistment of Ansar into the Sudanese Defence Force.

The Sudan Political Service

The Sudan Political Service was the name given to the cadre of officials of the Sudan Civil Service who were mainly engaged in administrative functions in Anglo-Egyptian Sudan between 1899 and 1955 (or 1956). They were distinguished from those m ...

advised Archer to keep Abd al-Rahman at arm's length. In March 1926 Archer ignored this advice and made an official visit to Abd al-Rahman on Aba Island accompanied by a full escort of troops and officials. When Archer arrived on 14 February, he was formally welcomed by Sayyid Abd al-Rahman with 1,500 Ansar supporters. Escorted by horsemen, the dignitaries went on by car to a reception at Abd al-Rahman's house. Replying to a speech by Abd al-Rahman, Archer said his visit marked "an important stage forward in the relations" between Abd al-Rahman and his followers and the government. Archer said he had come to cement the ties of friendship and understanding.

Archer's visit precipitated a crisis in the colonial administration. It was felt he had been far too friendly to Abd al-Rahman, who was viewed with suspicion by many administrators. Archer was forced to resign, and was replaced by Sir John Maffey. Abd al-Rahman was placed under restriction on his ability to travel outside Omdurman and Khartoum and was told to instruct his supporters to halt their political and religious activities.

Growing influence and British hostility

Sayyid Abd al-Rahman invited the Yemenite scholar Abd al-Rahman ibn Hurayn al-Jabri to come to Omdurman and make a study of Mahdism. Al-Jabri wrote a book covering the history of the movement and its justification in the ''hadith'', essentially designed to glorify the Mahdi and his son. Abd al-Rahman tried to publish the book in either 1925 or 1926, but the British confiscated the manuscript, which they considered to be highly seditious. To avoid publicity, they did not prosecute al-Jabri but quietly deported him. Abd al-Rahman made overtures to the "effendiyya", the growing elite of educated people in Sudan, patronising their social and educational institutions. He became the acknowledged leader of a group ofintelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a status class composed of the university-educated people of a society who engage in the complex mental labours by which they critique, shape, and lead in the politics, policies, and culture of their society; as such, the i ...

who were opposed to indirect rule or unification with Egypt, and were building a Sudanese national movement. In 1931 the colonial government lowered the starting rates of pay for Sudanese officials. After protests and demonstrations were ignored, a general strike was declared on 24 November 1931. With no other leader taking the initiative, it was left to Sayyid Abd al-Rahman to act as mediator and he successfully brought the strike to an end. This helped consolidate his position as a leader in the eyes of intelligentsia.

In 1935 Sayyid Abd al-Rahman founded ''al-Nil'' (''The Nile''), an organ of the Ansar and the first daily newspaper in Sudan written in Arabic

Arabic (, , or , ) is a Central Semitic languages, Central Semitic language of the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family spoken primarily in the Arab world. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) assigns lang ...

. The newspaper helped him gain influence with the educated elite in Sudan, including politically oriented government officials, many of whom joined the Ansar and became lifetime adherents of Abd al-Rahman.

By the mid-1930s, the British realised that Abd al-Rahman expected to be recognized as royalty, had firm control over a thriving Mahdist movement, and was actively seeking new adherents. British officials became increasingly suspicious of his motives, and their correspondence showed a mixture of hostility and fear of his growing influence. In 1933, and more forcefully in 1934, during Muhammad's birthday

The Mawlid () is an annual festival commemorating the birthday of the Islamic prophet Muhammad on the traditional date of 12 Rabi' al-Awwal, the third month of the Islamic calendar. A day central to the traditions of some Sunnis, Mawlid is also ...

celebrations Abd al-Rahman displayed signs with "various expressions advertising the Mahdi's prophetic standing". Sir Stewart Symes, Governor-General of Sudan from 1934 to 1940, sternly warned him to remove the signs or face consequences.

A British view of Abd al-Rahman at this time was given by Sir Stewart Symes, writing in April 1935, "He has the defects of a Sudanese of his type, the liking of intrigue, vanity, irrelevance and opportunism. On the other hand, he has quick perceptions, panache and subtle tenacity of purpose... He has used r misused

R, or r, is the eighteenth letter of the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''ar'' (pronounced ), plural ''ars''.

The letter ...

the opportunities ... of laying the foundations of his Mahdist organisation in the provinces... His favourite role is that of the loyal supporter of Government who is maliciously misunderstood". Symes refused to take action to suppress neo-Mahdism, preferring to follow a policy of ensuring that Abd al-Rahman conformed to agreed guidelines of behaviour, with the implied threat of punishment if he broke those rules. He allowed some restrictions to be lifted, while retaining others.

Political activity under British rule

The British had ceded some power in Egypt with the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty of 1922 and more in the

The British had ceded some power in Egypt with the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty of 1922 and more in the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty of 1936

The Anglo-Egyptian Treaty of 1936 (officially, ''The Treaty of Alliance Between His Majesty, in Respect of the United Kingdom, and His Majesty, the King of Egypt'') was a treaty signed between the United Kingdom and the Kingdom of Egypt. The ...

. The 1936 treaty was designed to counter Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

's ambition to link Libya

Libya, officially the State of Libya, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to EgyptâLibya border, the east, Sudan to LibyaâSudan border, the southeast, Chad to ChadâL ...

to Ethiopia via Sudan in a new Italian empire. The treaty recognized Egyptian claims of sovereignty in Sudan in return for British rights in the Nile valley and the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal (; , ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, Indo-Mediterranean, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia (and by extension, the Sinai Peninsula from the rest ...

. It allowed for unrestricted immigration of Egyptians to Sudan and for the return of Egyptian troops. The Sudanese were not consulted.

In 1937, Abd al-Rahman visited England and Egypt, where he met with high-ranking officials and with King Farouk

Farouk I (; ''FÄrÅŦq al-Awwal''; 11 February 1920 â 18 March 1965) was the tenth ruler of Egypt from the Muhammad Ali dynasty and the penultimate King of Egypt and the Sudan, succeeding his father, Fuad I, in 1936 and reigning until his ...

. His purpose was to present Sudanese criticism of the Anglo-Egyptian treaty in person. He was openly critical of the Egyptian plans for unity of the Nile

The Nile (also known as the Nile River or River Nile) is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa. It has historically been considered the List of river sy ...

valley, which he considered unrealistic. In May 1937, his eldest son al-Siddiq al-Mahdi visited Egypt and was given a royal reception. These moves concerned the British, who saw them as potentially the start of a Mahdist alliance with Egypt, despite Abd al-Rahman's avowed Sudanese nationalism.

In the period before World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 â 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

(1939â1945) the British wanted to reduce growth of Egyptian influence in Sudan, which had become more likely as a result of the 1936 treaty, while also suppressing the ultra-nationalist neo-Mahdist movement. They gave their support to Sayyid Ali al-Mirghani of the Khatmiyyah sect as a counterpoise to Sayyid Abd al-Rahman. Sayyid Abd al-Rahman responded by telling the British that Sayyid Ali al-Mirghani was pro-Italian due to his family commitments in Eritrea

Eritrea, officially the State of Eritrea, is a country in the Horn of Africa region of East Africa, with its capital and largest city being Asmara. It is bordered by Ethiopia in the EritreaâEthiopia border, south, Sudan in the west, and Dj ...

, but this was not accepted by the British.

The government had promulgated the ''Powers of Nomad Shiekhs Ordinance'' in 1922, and had recognized and reinforced the judicial powers of over 300 tribal leaders by 1923. They had ignored the aspirations of educated Sudanese in government employment to take a greater role in administration. The principle of indirect rule had also given the Sayyids, including Abd al-Rahman, more power to prevent changes demanded by the secular opposition. In a shift of policy, the Graduates' General Congress was launched in 1938 as a forum for the intelligentsia of Sudan to express their opinions and as an alternative voice to that of the tribal leaders, who had become discredited.

In August and September 1940, the Congress became split between Ansar and Khatmiyya supporters. At first the Ansar were dominant, but they lost this position by the end of 1942. Many of Abd al-Rahman's supporters saw him as a source of financial backing and admired his advocacy of an independent Sudan, but did not follow him as a religious leader and were not members of the Ansar movement. By the end of 1942, the government had decided the Congress had no political value. The Mahdists had split into rival camps, other factions had emerged, and the attendees at the annual meeting of the Congress included artisans, merchants and illiterates.

In May 1944, the government created a central Advisory Council, with the full backing of Sayyid Abd al-Rahman. The majority of the Council members were Ansar or tribal leaders. Many educated Sudanese were suspicious of the Council and drifted towards the Khatmiyya side in the 1944 elections, not for religious reasons but because they were hostile to the government, wanted to retain links with Egypt as a counterpoise to British influence and did not want a monarchy under Sayyid Abd al-Rahman.

Lead-up to independence

In August 1944, Sayyid Abd al-Rahman met with senior Congress members and tribal leaders to discuss formation of a pro-independence political party that was not associated with Mahdism. The first step taken was to launch a new daily newspaper, ''al-Umma'' (The Community). In February 1945, the Umma party had been organised and the party's first secretary,Abdullah Khalil

Sayed Abdallah Khalil (; ) was a Sudanese politician who served as the second prime minister of Sudan.

Early life

Khalil was born in Omdurman and was of Kenzi Nubian origin.

Military service

Khalil served in the Egyptian Army from 1910 to 1924, ...

, applied for a government license. The constitution of the party made no mention of Sayyid Abd al-Rahman or of the Ansar; the only visible link to Abd al-Rahman was the party's reliance on him for funding. However, there were rumours that the Umma party had been created by the colonial government and aimed to place Sayyid Abd al-Rahman on the throne. These rumours persisted until June 1945, when the government publicly said it would not support a Mahdist monarchy.

Abd al-Rahman at this time was a flamboyant figure with broad popular support. His stature served to diminish that of the politicians, who were seen as his followers rather than as leaders. Abd al-Rahman could not afford a sudden British withdrawal, since that would open the door for an Egyptian take-over and the loss of his power. The British also were against an Egyptian take-over, but for different reasons. Yet Abd al-Rahman could not be seen as supporting an indefinite colonial status for Sudan, and continued to promote independence. Abd al-Rahman and the British were engaged in delicate and unstable arrangements characterised by mutual distrust.

When, in 1946, Ismail al-Azhari of the Sudanese al-Ashiqqa party began seeking support for unification of the Nile Valley, Abd al-Rahman was strongly opposed to any hint that the King of Egypt might have authority of any kind in Sudan. He and his followers set up an "Independence Front" and organised huge demonstrations throughout Sudan against the draft Anglo-Egyptian agreement on Sudan. In November 1946, Abd al-Rahman left with a delegation for London via Cairo. Completely ignored by the Egyptian government in Cairo, he talked with British Prime Minister Clement Attlee for two hours in London. When Attlee asked why the Sudanese had not spoken up while Egypt pressed its claims over Sudan for the last seventy years, Abd al-Rahman said that was because the British had excluded them from any talks. He went on to say the Sudanese would fight with all their power for independence.

Abd al-Rahman supported the work of the Legislative Assembly which began in December 1948. He saw it as the first time that Sudan's political and religious groups had been able to meet each other in a venue where the British could not stir up disputes between the different factions. He said that Ismail al-Azhari opposed the assembly purely because it would bring Sudan away from Egypt and nearer to full independence. In December 1950 a member of the Umma tabled a resolution asking the Governor-General to demand that Egypt and Britain grant Sudan independence at once. The British strongly opposed the measure, saying the assembly was not truly representative since the Khatmiyya had chosen not to participate. The resolution was passed by one vote. Abd al-Rahman and al-Azhari both claimed victory: Abd al-Rahman since the vote had been passed, and the al-Azhari since the British had said the assembly was not representative.

Sayyid Abd al-Rahman said that from then on the British did everything they could to break up the Umma party and to thwart him personally. They tried without success to get tribal chiefs and village leaders to leave the Umma. He claimed that it was the Umma that forced the British to establish a committee to start drafting a constitution for an independent Sudan in 1951, a constitution that was endorsed in April 1952. However, broader considerations were leading the British towards support for an independent Sudan despite attempts by the United States to persuade them to give Egypt a role.

Elections and independence

Egypt gained full independence with the Egyptian Revolution of 1952, Egyptian Revolution of 23 July 1952 in whichKing Farouk

Farouk I (; ''FÄrÅŦq al-Awwal''; 11 February 1920 â 18 March 1965) was the tenth ruler of Egypt from the Muhammad Ali dynasty and the penultimate King of Egypt and the Sudan, succeeding his father, Fuad I, in 1936 and reigning until his ...

was overthrown by a group of officers that included Gamal Abdel Nasser, who later to emerge as the sole ruler in 1954. Sayyid Abd al-Rahman visited London and met the British Foreign Secretary Sir Anthony Eden on 11 November 1952. On 10 January 1953 the Egyptian government ratified an Sudan Self-Government Statute, agreement with the Umma representatives and other pro-independence Sudanese parties that gave the Sudanese the right of self-determination. During a transition period of no longer than three years, it was intended that parliamentary elections would be held and a Sudanese government formed. British and Egyptian troops and officials would leave the country and would be replaced by Sudanese.

In 1953, Abd al-Rahman made a major proclamation in which he supported a republican system, "since the democratic republican system is a system deeply rooted in Islam, our pure, tolerant, and democratic religion". The first 1953 Sudanese parliamentary election, parliamentary elections were held that year. The National Unionist Party (NUP), the successor to the al-Ashiqqa party, gained a solid majority in parliament and Ismail al-Azhari became prime minister. The NUP victory, greatest in northern and central Sudan, may have partly been due to support from the Khatmiyya. Another factor may have been fear that the Umma party would try to re-establish a Mahdist state with Abd al-Rahman as king.

In August 1954, Sayyid Abd al-Rahman sponsored a tour of the south by Buth Diu of the Southern Liberal Party. In his speeches, Buth Diu quoted NUP campaign promises supporting a Federal system in which the southern provinces would have considerable autonomy. Prime Minister Azhari described this as seditious talk and threatened to use force to prevent secession from Sudan by the south. In May 1955, Ismail al-Azhari announced that Sudan would seek complete independence, a reversal of the earlier NUP position in favour of union with Egypt.

As Ismail al-Azhari began to assert his power, both Sayyid Ali al-Mirghani and Sayyid Abd al-Rahman became concerned that they would lose their political influence. From October 1955 Sayyid Ali began to seek ways to oust Ismail al-Azhari from power. A key issue was whether a Referendum, plebiscite should be held to determine if Sudan was to be independent of Egypt, which Sayyid Ali supported and Ismail al-Azhari opposed. To strengthen his position in parliament, Ismail al-Azhari started making overtures to associates of Sayyid Abd al-Rahman to explore the idea of an NUP-Umma coalition. Sudan formally became independent on 1 January 1956. On 2 February 1956 Ismail al-Azhari announced a new cabinet that included representatives of all political parties and factions.

The first parliamentary elections after independence were held on 27 February and 8 March 1958. The result was a victory for Abd al-Rahman's Umma Party, which won 63 of the 173 seats. The Southern Sudan Federal Party competed in the election, and won 40 of the 46 seats allocated to the southern provinces. The Federal party platform represented a serious challenge to the authorities. However, when it became clear that the party's demands for a federal structure would be ignored by the Constituent Assembly, on 16 June 1958 the southern MPs left parliament.

In November 1958, the army staged a coup led by General Ibrahim Abboud. Two days later Abd al-Rahman proclaimed his strong support for the army's action, saying "It grieves me greatly to say that the politicians who have led the political parties have all failed... This now is a day of release. The men of the Sudanese army have sprung up and taken matters into their own hands... They will not permit hesitation, anarchy or corruption to play havoc in this land ... God has placed at our disposal ... someone who will take up the reins of government with truth and decisiveness ... Rejoice at this blessed revolution and go to your work calmly and contentedly, to support the men of the Sudanese revolution". It is possible that Abd al-Rahman expected to be appointed president for life. If so, he was disappointed.

Legacy

Sayyid Abd al-Rahman died on 24 March 1959, aged 73. Throughout a long and turbulent career he had always been a strong and consistent leader of the neo-Mahdist movement. By the end of the condominium in 1956, Abd al-Rahman was reported to be the wealthiest of all Sudanese. The British would have preferred the Ansar movement to be purely religious in nature, but Sayyid Abd al-Rahman al-Mahdi was also a competent political leader of Sudan. Explanations for the resurgence of neo-Mahdism in Sudan have included the British need for a figurehead, Abd al-Rahman's financial influence as his cotton growing business expanded, or a resurgence of religious and nationalist feeling in the Ansar sect.

Abd al-Rahman's son Sayyid al-Siddiq al-Mahdi was Imam of the Ansar for the next two years. After al-Siddiq's death in 1961 he was succeeded as imam by his brother Sayyid Imam al-Hadi al-Mahdi, al-Hadi al-Mahdi, while al-Siddiq's son Sadiq al-Mahdi took over the leadership of the Umma party. Sadiq Al-Mahdi was arrested in 1970, and for many years alternated between spells in prison in Sudan and periods of exile. In 1985, Sadiq al-Mahdi, who studied at Oxford and fought for democracy, was again elected president of the Umma party. In the 1986 elections he became Prime Minister of Sudan, holding office until the government was overthrown by a Muslim Brotherhood coup d'ÃĐtat in 1989. After further imprisonment and exile, Sadiq al-Mahdi returned to Sudan in 2000 and in 2002 was elected Imam of the Ansar. In 2003 Sadiq Al-Mahdi was re-elected President of Umma.

Sayyid Abd al-Rahman died on 24 March 1959, aged 73. Throughout a long and turbulent career he had always been a strong and consistent leader of the neo-Mahdist movement. By the end of the condominium in 1956, Abd al-Rahman was reported to be the wealthiest of all Sudanese. The British would have preferred the Ansar movement to be purely religious in nature, but Sayyid Abd al-Rahman al-Mahdi was also a competent political leader of Sudan. Explanations for the resurgence of neo-Mahdism in Sudan have included the British need for a figurehead, Abd al-Rahman's financial influence as his cotton growing business expanded, or a resurgence of religious and nationalist feeling in the Ansar sect.

Abd al-Rahman's son Sayyid al-Siddiq al-Mahdi was Imam of the Ansar for the next two years. After al-Siddiq's death in 1961 he was succeeded as imam by his brother Sayyid Imam al-Hadi al-Mahdi, al-Hadi al-Mahdi, while al-Siddiq's son Sadiq al-Mahdi took over the leadership of the Umma party. Sadiq Al-Mahdi was arrested in 1970, and for many years alternated between spells in prison in Sudan and periods of exile. In 1985, Sadiq al-Mahdi, who studied at Oxford and fought for democracy, was again elected president of the Umma party. In the 1986 elections he became Prime Minister of Sudan, holding office until the government was overthrown by a Muslim Brotherhood coup d'ÃĐtat in 1989. After further imprisonment and exile, Sadiq al-Mahdi returned to Sudan in 2000 and in 2002 was elected Imam of the Ansar. In 2003 Sadiq Al-Mahdi was re-elected President of Umma.

Notes

Citations

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Mahdi, Abd al-Rahman al- 1885 births 1959 deaths 20th-century Sudanese politicians Al-Mahdi family, Abd Mahdism People from Omdurman Knights Commander of the Order of the British Empire Slave owners 19th-century slave traders 20th-century slave traders