أژle Amsterdam on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

(), also known as Amsterdam Island or New Amsterdam (), is an island of the

Ile Amsterdam

Under the

The island is home to the

The island is home to the

Both the Plateau des Tourbiأ¨res and Falaises d'Entrecasteaux have been identified as

Restoration of Amsterdam Island, South Indian Ocean, following control of feral cattle

In 2007 it was decided to eradicate the population of cattle entirely, resulting in the slaughter of the cattle between 2008 and 2010.Sophie Lautier: "Sur l'أ®le Amsterdam, chlorophylle et miaulements".

Ile Amsterdam visit

(photos from a tourist's recent visit)

French Colonies – Saint-Paul & Amsterdam Islands

''Discover France''

French Southern and Antarctic Lands

at the CIA World Factbook *

Antipodes of the US

{{DEFAULTSORT:Amsterdam, Ile

French Southern and Antarctic Lands

The French Southern and Antarctic Lands (, TAAF) is an overseas territory ( or ) of France. It consists of:

* Adأ©lie Land (), the French claim on the continent of Antarctica.

* Crozet Islands (), a group in the southern Indian Ocean, south ...

in the southern Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or approximately 20% of the water area of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia (continent), ...

that together with neighbouring أژle Saint-Paul

is an island forming part of the French Southern and Antarctic Lands (, TAAF) in the Indian Ocean, with an area of . The island is located about south of the larger أژle Amsterdam , northeast of the Kerguelen Islands, and southeast of Rأ©uni ...

to the south forms one of the five districts of the territory.

The island is roughly equidistant

A point is said to be equidistant from a set of objects if the distances between that point and each object in the set are equal.

In two-dimensional Euclidean geometry, the locus of points equidistant from two given (different) points is t ...

to the land masses of Madagascar

Madagascar, officially the Republic of Madagascar, is an island country that includes the island of Madagascar and numerous smaller peripheral islands. Lying off the southeastern coast of Africa, it is the world's List of islands by area, f ...

, Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country comprising mainland Australia, the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania and list of islands of Australia, numerous smaller isl ...

, and Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean (also known as the Antarctic Ocean), it contains the geographic South Pole. ...

as well as the British Indian Ocean Territory

The British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT) is an British Overseas Territories, Overseas Territory of the United Kingdom situated in the Indian Ocean, halfway between Tanzania and Indonesia. The territory comprises the seven atolls of the Chago ...

and the Cocos (Keeling) Islands

The Cocos (Keeling) Islands (), officially the Territory of Cocos (Keeling) Islands (; ), are an Australian external territory in the Indian Ocean, comprising a small archipelago approximately midway between Australia and Sri Lanka and rel ...

(about from each). It is the northernmost volcanic island

Geologically, a volcanic island is an island of volcanic origin. The term high island can be used to distinguish such islands from low islands, which are formed from sedimentation or the uplifting of coral reefs (which have often formed ...

within the Antarctic Plate.

The research station

Research stations are facilities where scientific investigation, Data collection, collection, analysis and experimentation occurs. A research station is a facility that is built for the purpose of conducting scientific research. There are also man ...

at , first called and then , is the only settlement on the island and is the seasonal home to about thirty researchers and staff studying biology, meteorology, and geomagnetics

Earth's magnetic field, also known as the geomagnetic field, is the magnetic field that extends from Earth's interior out into space, where it interacts with the solar wind, a stream of charged particles emanating from the Sun. The magn ...

.

History

The first person known to have sighted the island was the Spanish explorer Juan Sebastiأ،n Elcano, on 18 March 1522, during hiscircumnavigation

Circumnavigation is the complete navigation around an entire island, continent, or astronomical object, astronomical body (e.g. a planet or natural satellite, moon). This article focuses on the circumnavigation of Earth.

The first circumnaviga ...

of the world. Elcano called it (), because he couldn't find a safe place to land and his crew was desperate for water after 40 days of sailing from Timor. On 17 June 1633, Dutch colonial governor and mariner Anthonie van Diemen sighted the island, and named it after his ship, . The first recorded landing on the island occurred in December 1696, led by the Dutch explorer Willem de Vlamingh.

French mariner Pierre Franأ§ois Pأ©ron wrote that he was marooned on the island between 1792 and 1795. Pأ©ron's , in which he describes his experiences, were published in a limited edition, now an expensive collectors' item. However, and were often confused at the time, and Pأ©ron may have been marooned on Saint-Paul.

Amsterdam and St. Paul islands were recommended in 1786 for a convict settlement by Alexander Dalrymple

Alexander Dalrymple (24 July 1737 – 19 June 1808) was a Scottish geographer, hydrographer, and publisher. He spent the greater part of his career with the British East India Company, starting as a writer in Madras at the age of 16. He s ...

, the Examiner of Sea-Journals for the East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company that was founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to Indian Ocean trade, trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (South A ...

, when the British government was considering New South Wales and Norfolk Island

Norfolk Island ( , ; ) is an States and territories of Australia, external territory of Australia located in the Pacific Ocean between New Zealand and New Caledonia, directly east of Australia's Evans Head, New South Wales, Evans Head and a ...

for such a settlement. An investigation of those islands was subsequently undertaken in December 1792 and January 1793 by George Lord Macartney, Britain's first ambassador to China, during his voyage to that country, and he concluded that they were not suitable for settlement.

Sealers are said to have landed on the island, for the first time, in 1789. Between that date and 1876, 47 sealing vessels are recorded at the island, 9 of which were wrecked. Relics of the sealing era can still be found.

The island was a stop on the British Macartney Embassy

The Macartney Embassy ( zh, t=馬هٹ 爾ه°¼ن½؟هœک), also called the Macartney Mission, was the first British diplomatic mission to China, which took place in 1793. It is named for its leader, George Macartney, Great Britain's first envoy to Ch ...

on its voyage to China in 1793.

On 11 October 1833, the British barque

A barque, barc, or bark is a type of sailing ship, sailing vessel with three or more mast (sailing), masts of which the fore mast, mainmast, and any additional masts are Square rig, rigged square, and only the aftmost mast (mizzen in three-maste ...

''Lady Munro'' was wrecked at the island. Of the 97 persons aboard, 21 survivors were picked up two weeks later by a US sealing schooner

A schooner ( ) is a type of sailing ship, sailing vessel defined by its Rig (sailing), rig: fore-and-aft rigged on all of two or more Mast (sailing), masts and, in the case of a two-masted schooner, the foremast generally being shorter than t ...

, ''General Jackson''.

John Balleny in command of the exploration and sealing vessel visited the island in November 1838 in search of seals. He returned with a few fish and reported having seen the remains of a hut and the carcass of a whale.

The islands of and were first claimed by France in June 1843. A decree of 8 June 1843 mandated the Polish captain Adam Mieroslawski to take into possession and administer in the name of France both islands. The decree as well as the ship's log from ''Olympe'' from 1 and 3 July 1843, stating that the islands had been taken into possession by Mieroslawski, are still preserved.

However, the French government renounced its possession of the islands in 1853.

In January 1871 an attempt to settle the island was made by a party led by Heurtin, a French resident of Rأ©union

Rأ©union (; ; ; known as before 1848) is an island in the Indian Ocean that is an overseas departments and regions of France, overseas department and region of France. Part of the Mascarene Islands, it is located approximately east of the isl ...

. After seven months, their attempts to raise cattle and grow crops were fruitless, and they returned to Rأ©union, abandoning the cattle on the island.

In May 1880 circumnavigated the island searching for missing ship ''Knowsley Hall''. A cutter and gig were despatched to the island to search for signs of habitation. There was a flagpole on Hoskin Point and north were two huts, one of which had an intact roof and contained three bunks, empty casks, an iron pot and the eggshells and feathers of sea-birds. There was also an upturned serviceable boat in the other hut, believed to belong to the fishermen who visited the island.

In 1892, the crew of the French sloop ''Bourdonnais'', followed by the ship ''L'Eure'' in 1893, again took possession of Saint-Paul and Amsterdam Island in the name of the French government.

The island was attached to the French colony of Madagascar from 21 November 1924 until 6 August 1955 when the French Southern and Antarctic Lands was formed. (Madagascar gained independence in 1958.)

The first French base on was established in 1949, and was originally called . It is now the research station, named after Paul de Martin de Viviأ¨s who, with twenty-three others, spent the winter of 1949 on the island. The station was originally named Camp Heurtin and has been in operation since 1 January 1981, superseding the first station, .

The Global Atmosphere Watch still maintains a presence on أژle Amsterdam.

On 15 January 2025, a wildfire broke out on the island, forcing the evacuation of all 31 residents by boat to Rأ©union

Rأ©union (; ; ; known as before 1848) is an island in the Indian Ocean that is an overseas departments and regions of France, overseas department and region of France. Part of the Mascarene Islands, it is located approximately east of the isl ...

. Due to the island's remote location, the fire spread unchecked. By 10 February, 45% of the island's area had been affected, while water supply and telecommunications infrastructure at the research station was damaged.

Amateur radio

From 1987 to 1998, there were frequentamateur radio

Amateur radio, also known as ham radio, is the use of the radio frequency radio spectrum, spectrum for purposes of non-commercial exchange of messages, wireless experimentation, self-training, private recreation, radiosport, contesting, and emer ...

operations from Amsterdam Island. There was a resident radio amateur operator in the 1950s, using callsign

In broadcasting and radio communications, a call sign (also known as a call name or call letters—and historically as a call signal—or abbreviated as a call) is a unique identifier for a transmitter station. A call sign can be formally assi ...

FB8ZZ.

In January 2014 Clublog listed Amsterdam and St Paul Islands as the seventh most-wanted DXCC

An amateur radio operating award is earned by an amateur radio operator for establishing two-way communication (or "working") with other amateur radio stations. Awards are sponsored by national amateur radio societies, radio enthusiast magazine ...

entity. On 25 January 2014 a DX-pedition landed on Amsterdam Island using MV ''Braveheart'' and began amateur radio operations from two separate locations using callsign FT5ZM. The DX-pedition remained active until 12 February and achieved over 170,000 two-way contacts with amateur radio stations worldwide.

Environment

Geography

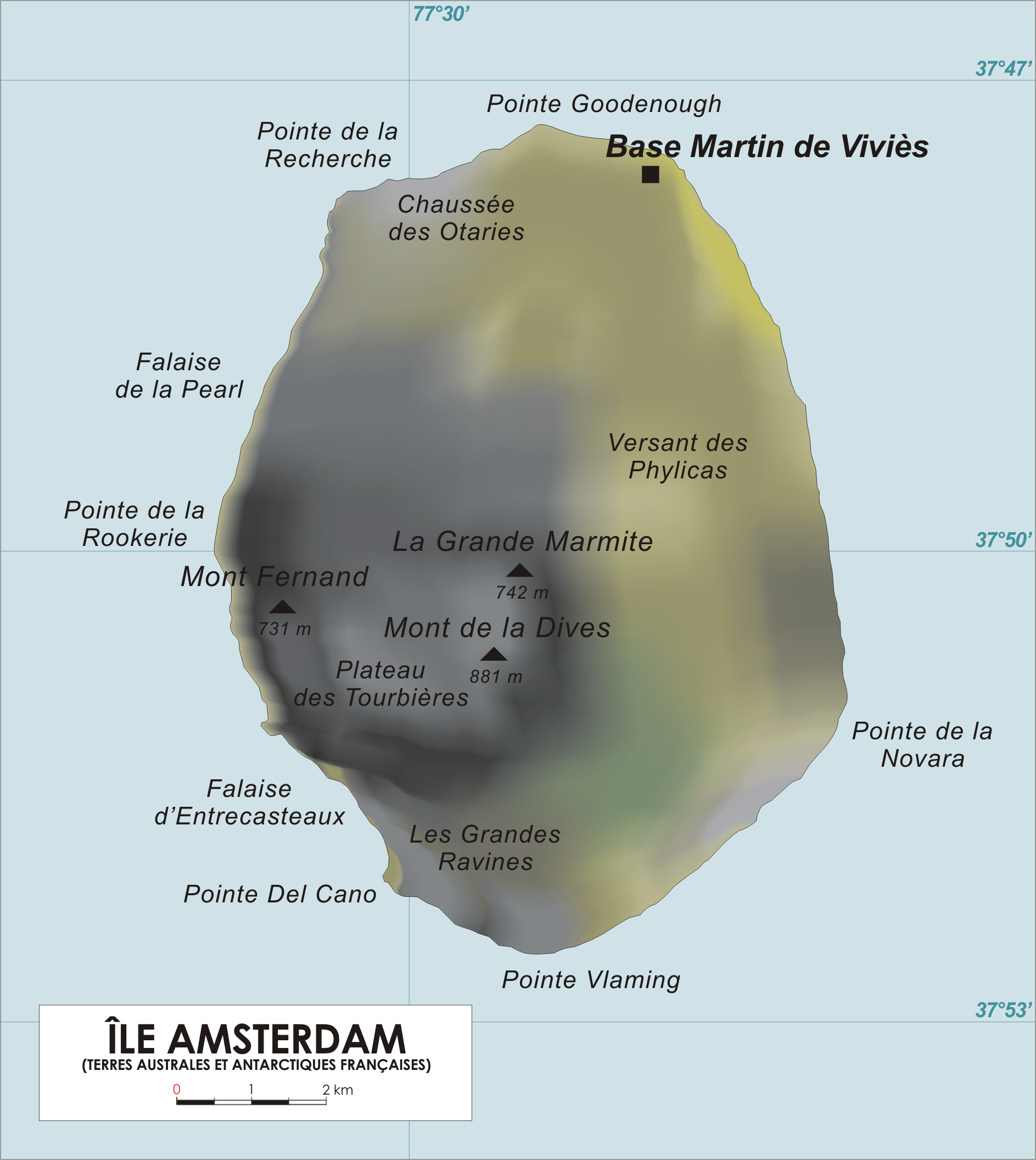

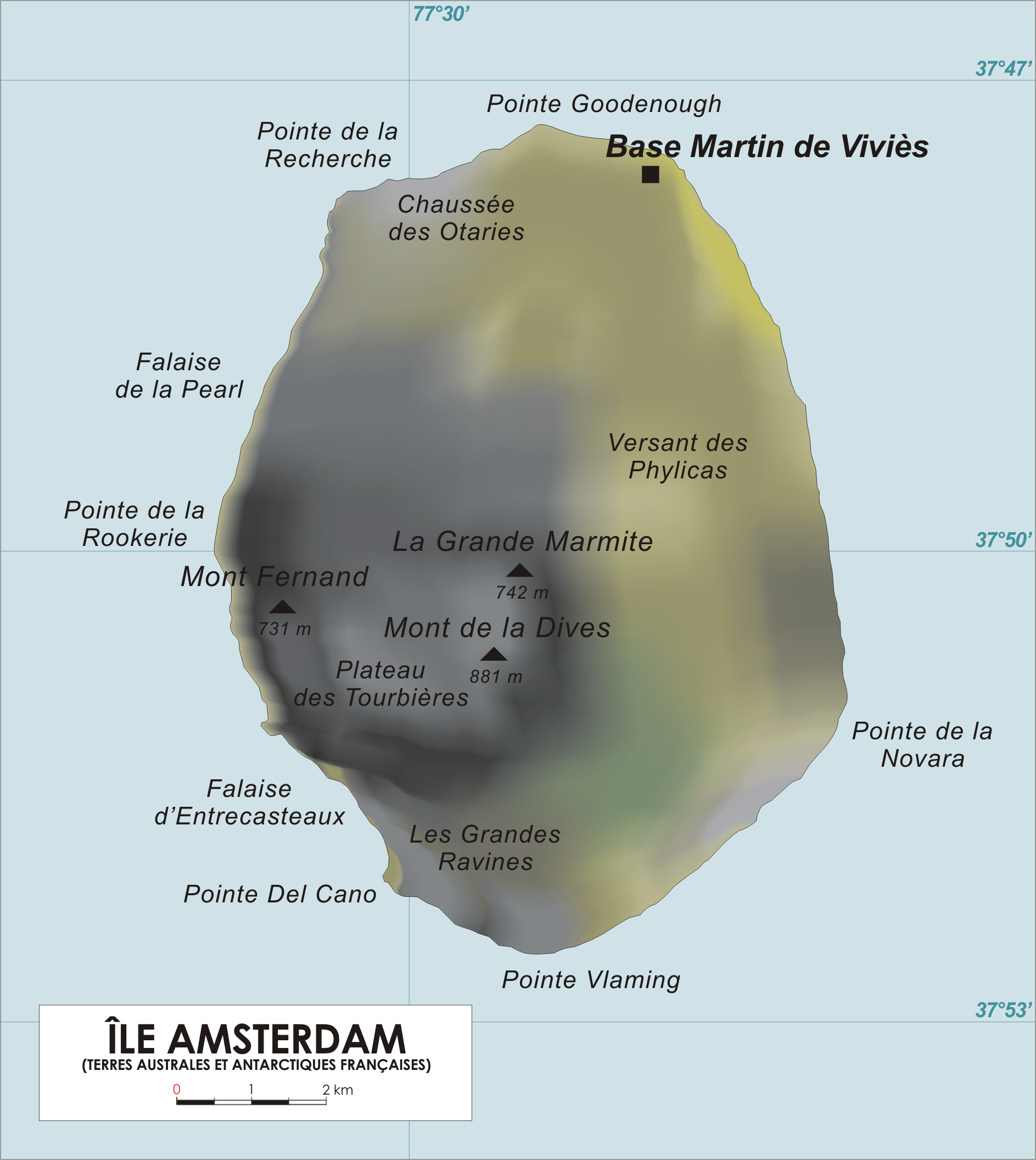

The island is a potentially active volcano. It has an area of , measuring about on its longest side, and reaches as high as at the Mont de la Dives. The high central area of the island, at an elevation of over , containing its peaks and caldera, is known as the (). The cliffs that characterise the western coastline of the island, rising to over , are known as the Falaises d'Entrecasteaux after the 18th-century French navigatorAntoine Bruni d'Entrecasteaux

Antoine Raymond Joseph de Bruni, chevalier d'Entrecasteaux (; 8 November 1737 – 21 July 1793) was a French Navy officer, explorer and colonial administrator who served as the Governor of Isle de France (Mauritius), governor of Isle de Fran ...

.BirdLife International. (2012). Important Bird Areas factsheet: Falaises d'Entrecasteaux. Downloaded from http://www.birdlife.org on 2012-01-08.

Geology

No historical eruptions are known, although the fresh morphology of the latest volcanism at Dumas Craters on the northeastern flank suggests it may have occurred as recently as the late 19th century. All the rocks are tholeiitic basalt and the oldest basalt sampled is no more than 720,000 years old. There are two stratovolcanoes being which dominates and is younger and Le Mount du Fernand. Vents manifest as either cones or craters include Cratere Antonelli, Le Brulot, Le Chaudron, Le Cyclope, Crateres Dumas, Le Forneau, Cratere Inferieur, Grande Marmite, Cratere Hebert, Museau De Tanche, Cratere de l'Olympe, Cratere Superieur, Crateres Venus, and Cratere Vulcain (see map on this page). The island is located on the mainly undersea Amsterdam–Saint Paul Plateau which is of volcanic hotspot origin. There is a magma chamber located at between depth below Amsterdam Island. The plateau which extends north west towards the Nieuw Amsterdam Fracture Zone (Amsterdam Fracture Zone) and south to beyond the island of St Paul with its presently known active area being delimited by the St. Paul Fracture Zone, is a feature of the sea floor near theSoutheast Indian Ridge

The Southeast Indian Ridge (SEIR) is a mid-ocean ridge in the southern Indian Ocean. A divergent tectonic plate boundary stretching almost between the Rodrigues triple junction () in the Indian Ocean and the Macquarie triple junction () in the ...

, which is an active spreading center between the Antarctic plate that the island lies on, and the Australian Plate

The Australian plate is or was a major tectonic plate in the eastern and, largely, southern hemispheres. Originally a part of the ancient continent of Gondwana, Australia remained connected to India and Antarctica until approximately when Indi ...

. Helium isotopic compositional studies are consistent with its formation from the combined effects of accretion at the mid-ocean ridge

A mid-ocean ridge (MOR) is a undersea mountain range, seafloor mountain system formed by plate tectonics. It typically has a depth of about and rises about above the deepest portion of an ocean basin. This feature is where seafloor spreading ...

ridge and mantle plume activity of a hot spot. This is either the Kerguelen hotspot

The Kerguelen hotspot is a volcanic hotspot at the Kerguelen Plateau in the Southern Indian Ocean. The Kerguelen hotspot has produced basaltic lava for about 130 million years and has also produced the Kerguelen Islands, Naturaliste Plateau, H ...

or a potentially separate Amsterdam-Saint Paul hotspot but resolution of this issue is complicated by the recent volcanism on the island due to it being adjacent to the Southeast Indian Ridge. Recent authors have favoured a separate Amsterdam and St. Paul hotspot. There has been evidence at Boomerang Seamount

The Boomerang Seamount is an active submarine volcano, located northeast of Amsterdam Island, France. It was formed by the Amsterdam-Saint Paul hotspot and has a wide caldera that is deep. Hydrothermal activity occurs within the caldera. Th ...

to the north east of the island that Kerguelen-type source mantle exists beneath the Amsterdam and St. Paul Plateau. Which ever hot spot is responsible is moving south as أژle Amsterdam rocks are older than St. Paul rocks. The Amsterdam–St. Paul Plateau while formed in the last 10 million years, started this formation beneath the Australian Plate so the island is built on the components of two tectonic plates.

Climate

أژle Amsterdam has a mild,oceanic climate

An oceanic climate, also known as a marine climate or maritime climate, is the temperate climate sub-type in Kأ¶ppen climate classification, Kأ¶ppen classification represented as ''Cfb'', typical of west coasts in higher middle latitudes of co ...

, ''Cfb'' under the Kأ¶ppen climate classification

The Kأ¶ppen climate classification divides Earth climates into five main climate groups, with each group being divided based on patterns of seasonal precipitation and temperature. The five main groups are ''A'' (tropical), ''B'' (arid), ''C'' (te ...

, with a mean annual temperature of , annual rainfall of , persistent westerly winds and high levels of humidity.Trewartha climate classification

The Trewartha climate classification (TCC), or the Kأ¶ppen–Trewartha climate classification (KTC), is a climate classification system first published by American geographer Glenn Thomas Trewartha in 1966. It is a modified version of the Kأ¶p ...

the island is well inside the maritime subtropical

The subtropical zones or subtropics are geographical zone, geographical and Kأ¶ppen climate classification, climate zones immediately to the Northern Hemisphere, north and Southern Hemisphere, south of the tropics. Geographically part of the Ge ...

zone due to its very low diurnal temperature variation

In meteorology, diurnal temperature variation is the variation between a high air temperature and a low temperature that occurs during the same day.

Temperature lag

Temperature lag, also known as thermal inertia, is an important factor in diur ...

keeping means high.

Flora and fauna

Vegetation

'' Phylica arborea'' trees occur on Amsterdam, which is the only place where they form a low forest, although the trees are also found onTristan da Cunha

Tristan da Cunha (), colloquially Tristan, is a remote group of volcano, volcanic islands in the South Atlantic Ocean. It is one of three constituent parts of the British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory of Saint Helena, Ascensi ...

and Gough Island

Gough Island ( ), also known historically as Gonأ§alo أپlvares, is a rugged volcanic island in the South Atlantic Ocean. It is a dependency of Tristan da Cunha and part of the British overseas territory of Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan d ...

. It was called the ''Great Forest'' (), which covered the lowlands of the island until forest fires set by sealers cleared much of it in 1825. Only eight fragments remain. Sailors from , who visited the island on 27 May 1880, described the vegetation as:

Birds

The island is home to the

The island is home to the endemic

Endemism is the state of a species being found only in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also foun ...

Amsterdam albatross, which breeds only on the Plateau des Tourbiأ¨res. Other rare species are the brown skua, Antarctic tern and western rockhopper penguin. The Amsterdam duck is now extinct

Extinction is the termination of an organism by the death of its Endling, last member. A taxon may become Functional extinction, functionally extinct before the death of its last member if it loses the capacity to Reproduction, reproduce and ...

, as are the local breeding populations of several petrel

Petrels are tube-nosed seabirds in the phylogenetic order Procellariiformes.

Description

Petrels are a monophyletic group of marine seabirds, sharing a characteristic of a nostril arrangement that results in the name "tubenoses". Petrels enco ...

s. There was once possibly a species of rail inhabiting the island, as a specimen was taken in the 1790s (which has been lost), but this was either extinct by 1800 or was a straggler of an extant species. The common waxbill has been introduced.Amsterdam Island – Introduced faunaBoth the Plateau des Tourbiأ¨res and Falaises d'Entrecasteaux have been identified as

Important Bird Area

An Important Bird and Biodiversity Area (IBA) is an area identified using an internationally agreed set of criteria as being globally important for the conservation of bird populations.

IBA was developed and sites are identified by BirdLife Int ...

s by BirdLife International

BirdLife International is a global partnership of non-governmental organizations that strives to conserve birds and their habitats. BirdLife International's priorities include preventing extinction of bird species, identifying and safeguarding i ...

, the latter for its large breeding colony of Indian yellow-nosed albatrosses.

Mammals

There are no native land mammals. Subantarctic fur seals andsouthern elephant seal

The southern elephant seal (''Mirounga leonina'') is one of two species of elephant seals. It is the largest member of the clade Pinnipedia and the order Carnivora, as well as the largest extant marine mammal that is not a cetacean. It gets its ...

s breed on the island. Introduced mammals include the house mouse

The house mouse (''Mus musculus'') is a small mammal of the rodent family Muridae, characteristically having a pointed snout, large rounded ears, and a long and almost hairless tail. It is one of the most abundant species of the genus '' Mus''. A ...

, brown rat

The brown rat (''Rattus norvegicus''), also known as the common rat, street rat, sewer rat, wharf rat, Hanover rat, Norway rat and Norwegian rat, is a widespread species of common rat. One of the largest Muroidea, muroids, it is a brown or grey ...

and feral cat

A feral cat or a stray cat is an unowned domestic cat (''Felis catus'') that lives outdoors and avoids human contact; it does not allow itself to be handled or touched, and usually remains hidden from humans. Feral cats may breed over dozens ...

s. An eradication campaign of these invasive species was started in 2023, which plans to eradicate all cats and rats from the island by late 2024.

A distinct breed of wild cattle, Amsterdam Island cattle, also inhabited the island from 1871 to 2010. They originated from the introduction of five animals by Heurtin during his brief attempt at settlement of the island in 1871 and by 1988 had increased to an estimated 2,000. Following recognition that the cattle were damaging the island ecosystems, a fence was built restricting them to the northern part of the island.Micol, T. & Jouventin, P. (1995). Restoration of Amsterdam Island, South Indian Ocean, following control of feral cattle. ''Biological Conservation'' 73(3): 199–20Restoration of Amsterdam Island, South Indian Ocean, following control of feral cattle

In 2007 it was decided to eradicate the population of cattle entirely, resulting in the slaughter of the cattle between 2008 and 2010.Sophie Lautier: "Sur l'أ®le Amsterdam, chlorophylle et miaulements".

See also

* List of volcanoes in French Southern and Antarctic Lands *French overseas departments and territories

Overseas France (, also ) consists of 13 French territories outside Europe, mostly the remnants of the French colonial empire that remained a part of the French state under various statuses after decolonisation. Most are part of the Europea ...

* Administrative divisions of France

The administrative divisions of France are concerned with the institutional and territorial organization of French territory. These territories are located in many parts of the world. There are many administrative divisions, which may have ...

* List of French islands in the Indian and Pacific oceans

References

Further reading

* *External links

*Ile Amsterdam visit

(photos from a tourist's recent visit)

French Colonies – Saint-Paul & Amsterdam Islands

''Discover France''

French Southern and Antarctic Lands

at the CIA World Factbook *

Antipodes of the US

{{DEFAULTSORT:Amsterdam, Ile

Amsterdam

Amsterdam ( , ; ; ) is the capital of the Netherlands, capital and Municipalities of the Netherlands, largest city of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. It has a population of 933,680 in June 2024 within the city proper, 1,457,018 in the City Re ...

Volcanoes of the French Southern and Antarctic Lands

Dormant volcanoes

Seal hunting