Émile Zola on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Émile Édouard Charles Antoine Zola (, ; ; 2 April 184029 September 1902) was a French novelist, journalist, playwright, the best-known practitioner of the literary school of naturalism, and an important contributor to the development of theatrical naturalism. He was a major figure in the political

''Émile Zola''

/ref> Before his breakthrough as a writer, Zola worked for minimal pay as a clerk in a shipping firm and then in the sales department for the publisher Hachette. He also wrote literary and art reviews for newspapers. As a political journalist, Zola did not hide his dislike of

Zola died on 29 September 1902 of

Zola died on 29 September 1902 of

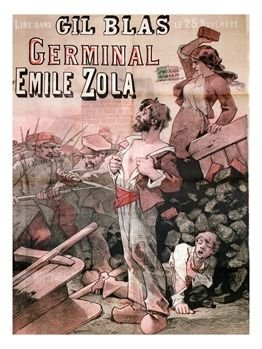

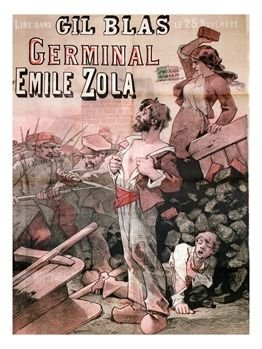

In the Rougon-Macquart novels, provincial life can seem to be overshadowed by Zola's preoccupation with the capital. However, the following novels (see the individual titles in the Livre de poche series) scarcely touch on life in Paris: '' La Terre'' (peasant life in Beauce), '' Le Rêve'' (an unnamed cathedral city), '' Germinal'' (collieries in the northeast of France), '' La Joie de vivre'' (the Atlantic coast), and the four novels set in and around Plassans (modelled on his childhood home, Aix-en-Provence), (, '' La Conquête de Plassans'', '' La Faute de l'Abbé Mouret'' and '' Le Docteur Pascal''). '' La Débâcle'', the military novel, is set for the most part in country districts of eastern France; its dénouement takes place in the capital during the civil war leading to the suppression of the

In the Rougon-Macquart novels, provincial life can seem to be overshadowed by Zola's preoccupation with the capital. However, the following novels (see the individual titles in the Livre de poche series) scarcely touch on life in Paris: '' La Terre'' (peasant life in Beauce), '' Le Rêve'' (an unnamed cathedral city), '' Germinal'' (collieries in the northeast of France), '' La Joie de vivre'' (the Atlantic coast), and the four novels set in and around Plassans (modelled on his childhood home, Aix-en-Provence), (, '' La Conquête de Plassans'', '' La Faute de l'Abbé Mouret'' and '' Le Docteur Pascal''). '' La Débâcle'', the military novel, is set for the most part in country districts of eastern France; its dénouement takes place in the capital during the civil war leading to the suppression of the

In Zola there is the theorist and the writer, the poet, the scientist and the optimist – features that are basically joined in his own confession of

In Zola there is the theorist and the writer, the poet, the scientist and the optimist – features that are basically joined in his own confession of

Émile Zola Collection

at the

Life of Émile Zola on NotreProvence.fr

Émile Zola at InterText Digital Library

Émile Zola at Livres & Ebooks

Émile Zola exhibition

at the

Lorgues, Plassans

Livres audio gratuits pour Émile Zola

*

Works about Émile Zola

at the

References to Émile Zola in historic European newspapers

Emile Zola Writes a Letter to Alfred Dreyfus at the Height of the Dreyfus Affair

{{DEFAULTSORT:Zola, Emile 1840 births 1902 deaths Naturalized citizens of France 19th-century French dramatists and playwrights 19th-century French journalists 19th-century French male writers 19th-century French novelists 20th-century French male writers 20th-century French novelists Accidental deaths in France Burials at Montmartre Cemetery Burials at the Panthéon, Paris Deaths from carbon monoxide poisoning Dreyfusards French male novelists French male journalists French people of Italian descent French people of Greek descent French psychological fiction writers Lycée Saint-Louis alumni People from Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur People of Venetian descent Unsolved deaths in France Writers from Paris French literary critics French literary theorists 19th-century French photographers 19th-century French short story writers French male short story writers 19th-century French essayists French art critics French librettists

liberalization

Liberalization or liberalisation (British English) is a broad term that refers to the practice of making laws, systems, or opinions less severe, usually in the sense of eliminating certain government regulations or restrictions. The term is used ...

of France and in the exoneration of the falsely accused and convicted army officer Alfred Dreyfus

Alfred Dreyfus (9 October 1859 – 12 July 1935) was a French Army officer best known for his central role in the Dreyfus affair. In 1894, Dreyfus fell victim to a judicial conspiracy that eventually sparked a major political crisis in the Fre ...

, which is encapsulated in his renowned newspaper opinion headlined '' J'Accuse...!'' Zola was nominated for the first and second Nobel Prizes in Literature in 1901 and 1902.

Early life

Zola was born in Paris in 1840 to François Zola (originally Francesco Zolla) and Émilie Aubert. His father was an Italian engineer with someGreek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

ancestry, who was born in Venice

Venice ( ; ; , formerly ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 islands that are separated by expanses of open water and by canals; portions of the city are li ...

in 1795, and engineered the Zola Dam in Aix-en-Provence

Aix-en-Provence, or simply Aix, is a List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, city and Communes of France, commune in southern France, about north of Marseille. A former capital of Provence, it is the Subprefectures in France, s ...

; his mother was French. The family moved to Aix-en-Provence in the southeast

The points of the compass are a set of horizontal, Radius, radially arrayed compass directions (or Azimuth#In navigation, azimuths) used in navigation and cartography. A ''compass rose'' is primarily composed of four cardinal directions—north, ...

when Émile was three years old. In 1845, five-year-old Zola was sexually molested by an older boy. Two years later, in 1847, his father died, leaving his mother on a meager pension. In 1852, Zola entered the Collège Bourbon as a boarding student. He would later complain about poor nutrition and bullying

Bullying is the use of force, coercion, Suffering, hurtful teasing, comments, or threats, in order to abuse, aggression, aggressively wikt:domination, dominate, or intimidate one or more others. The behavior is often repeated and habitual. On ...

in school.

In 1858, the Zolas moved to Paris, where Émile's childhood friend Paul Cézanne

Paul Cézanne ( , , ; ; ; 19 January 1839 – 22 October 1906) was a French Post-Impressionism, Post-Impressionist painter whose work introduced new modes of representation, influenced avant-garde artistic movements of the early 20th century a ...

soon joined him. Zola started to write in the Romantic style. His widowed mother had planned a law career for Émile, but he failed his baccalauréat

The ''baccalauréat'' (; ), often known in France colloquially as the ''bac'', is a French national academic qualification that students can obtain at the completion of their secondary education (at the end of the ''lycée'') by meeting certain ...

examination twice. Larousse''Émile Zola''

/ref> Before his breakthrough as a writer, Zola worked for minimal pay as a clerk in a shipping firm and then in the sales department for the publisher Hachette. He also wrote literary and art reviews for newspapers. As a political journalist, Zola did not hide his dislike of

Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles-Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was President of France from 1848 to 1852 and then Emperor of the French from 1852 until his deposition in 1870. He was the first president, second emperor, and last ...

, who had successfully run for the office of president under the constitution of the French Second Republic

The French Second Republic ( or ), officially the French Republic (), was the second republican government of France. It existed from 1848 until its dissolution in 1852.

Following the final defeat of Napoleon, Napoleon Bonaparte at the Battle ...

, only to use this position as a springboard for the coup d'Ă©tat that made him emperor.

Later life

In 1862 Zola was naturalized as a French citizen. In 1865, he met Éléonore-Alexandrine Meley, who called herself Gabrielle, a seamstress. They married on 31 May 1870. Together they cared for Zola's mother. She stayed with him all his life and was instrumental in promoting his work. The marriage remained childless. Alexandrine Zola had had a child before she met Zola that she had given up, because she had been unable to take care of it. When she confessed this to Zola after their marriage, they went looking for the girl, but she had died a short time after birth. In 1888, he was given a camera, but he only began to use it in 1895 and attained a near professional level of expertise. Also in 1888, Alexandrine hired Jeanne Rozerot, a 21-year-old seamstress who was to live with them in their home in Médan. The 48-year-old Zola fell in love with Jeanne and fathered two children with her: Denise in 1889 and Jacques in 1891. After Jeanne left Médan for Paris, Zola continued to support and visit her and their children. In November 1891 Alexandrine discovered the affair, but their marriage lasted until Zola's death. The discord was partially healed, which allowed Zola to take an increasingly active role in the lives of the children. After Zola's death, the children were given his name as their lawful surname.Career

During his early years, Zola wrote numerous short stories and essays, four plays, and three novels. Among his early books was ''Contes à Ninon'' ("Stories for Ninon"), published in 1864. With the publication of his sordid autobiographical novel ''La Confession de Claude'' (1865) attracting police attention, Hachette fired Zola. His novel ''Les Mystères de Marseille'' appeared as a serial in 1867. He was also an aggressive critic, his articles on literature and art appearing in Villemessant's journal ''L'Événement''. After his first major novel, '' Thérèse Raquin'' (1867), Zola started the series called . In Paris, Zola maintained his friendship with Cézanne, who painted a portrait of him with another friend from Aix-en-Provence, writerPaul Alexis

Antoine Joseph Paul Alexis (16 June 1847 – 28 July 1901) was a French novelist, dramatist, and journalist. He is best remembered today as the friend and biographer of Émile Zola.

Life

Alexis was born at Aix-en-Provence. He attended the Co ...

, entitled ''Paul Alexis Reading to Zola''.

Literary output

More than half of Zola's novels were part of the twenty-volume cycle, which details the history of a single family under the reign of Napoléon III. Unlike Balzac, who in the midst of his literary career resynthesized his work into '' La Comédie Humaine'', Zola from the start, at the age of 28, had thought of the complete layout of the series. Set in France's Second Empire, in the context of Baron Haussmann's changing Paris, the series traces the environmental and hereditary influences of violence, alcohol, and prostitution which became more prevalent during the second wave of theIndustrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution, sometimes divided into the First Industrial Revolution and Second Industrial Revolution, was a transitional period of the global economy toward more widespread, efficient and stable manufacturing processes, succee ...

. The series examines two branches of the family—the respectable (that is, legitimate) Rougons and the disreputable (illegitimate) Macquarts—over five generations.

In the preface to the first novel of the series, Zola states, "I want to explain how a family, a small group of regular people, behaves in society, while expanding through the birth of ten, twenty individuals, who seem at first glance profoundly dissimilar, but who are shown through analysis to be intimately linked to one another. Heredity has its own laws, just like gravity. I will attempt to find and to follow, by resolving the double question of temperaments and environments, the thread that leads mathematically from one man to another."

Although Zola and CĂ©zanne were friends from childhood, they experienced a falling out later in life over Zola's fictionalised depiction of CĂ©zanne and the Bohemian life of painters in Zola's novel (''The Masterpiece'', 1886).

From 1877, with the publication of '' L'Assommoir'', Émile Zola became wealthy; he was better paid than Victor Hugo

Victor-Marie Hugo, vicomte Hugo (; 26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885) was a French Romanticism, Romantic author, poet, essayist, playwright, journalist, human rights activist and politician.

His most famous works are the novels ''The Hunchbac ...

, for example. Because ''L'Assommoir'' was such a success, Zola was able to renegotiate his contract with his publisher Georges Charpentier to receive more than 14% royalties and the exclusive rights to serial publication in the press. Subsequently, sales of ''L'Assommoir'' were even exceeded by those of '' Nana'' (1880) and ''La Débâcle'' (1892). He became a figurehead among the literary bourgeoisie and organised cultural dinners with Guy de Maupassant, Joris-Karl Huysmans, and other writers at his luxurious villa (worth 300,000 francs) in Médan, near Paris, after 1880. Despite being nominated several times, Zola was never elected to the .

Zola's output also included novels on population (''Fécondité'') and work (''Travail''), a number of plays, and several volumes of criticism. He wrote every day for around 30 years, and took as his motto ("not a day without a line").

The self-proclaimed leader of French naturalism, Zola's works inspired operas such as those of Gustave Charpentier, notably '' Louise'' in the 1890s. His works were inspired by the concept of heredity

Heredity, also called inheritance or biological inheritance, is the passing on of traits from parents to their offspring; either through asexual reproduction or sexual reproduction, the offspring cells or organisms acquire the genetic infor ...

and milieu ( Claude Bernard and Hippolyte Taine

Hippolyte Adolphe Taine (21 April 1828 – 5 March 1893) was a French historian, critic and philosopher. He was the chief theoretical influence on French naturalism, a major proponent of sociological positivism and one of the first practitione ...

) and by the realism of Balzac and Flaubert. He also provided the libretto for several operas by Alfred Bruneau, including '' Messidor'' (1897) and '' L'Ouragan'' (1901); several of Bruneau's other operas are adapted from Zola's writing. These provided a French alternative to Italian verismo.

He is considered to be a significant influence on those writers that are credited with the creation of the so-called new journalism

New Journalism is a style of news writing and journalism, developed in the 1960s and 1970s, that uses literary techniques unconventional at the time. It is characterized by a subjective perspective, a literary style reminiscent of long-form no ...

: Wolfe, Capote, Thompson, Mailer, Didion, Talese and others.

Tom Wolfe

Thomas Kennerly Wolfe Jr. (March 2, 1930 – May 14, 2018)Some sources say 1931; ''The New York Times'' and Reuters both initially reported 1931 in their obituaries before changing to 1930. See and was an American author and journalist widely ...

wrote that his goal in writing fiction was to document contemporary society in the tradition of John Steinbeck

John Ernst Steinbeck ( ; February 27, 1902 – December 20, 1968) was an American writer. He won the 1962 Nobel Prize in Literature "for his realistic and imaginative writings, combining as they do sympathetic humor and keen social percep ...

, Charles Dickens, and Émile Zola.

Dreyfus affair

CaptainAlfred Dreyfus

Alfred Dreyfus (9 October 1859 – 12 July 1935) was a French Army officer best known for his central role in the Dreyfus affair. In 1894, Dreyfus fell victim to a judicial conspiracy that eventually sparked a major political crisis in the Fre ...

was a French-Jewish artillery officer in the French army. In September 1894, French intelligence discovered someone had been passing military secrets to the German Embassy. Senior officers began to suspect Dreyfus, though there was no direct evidence of any wrongdoing. Dreyfus was court-martialed, convicted of treason, and sent to Devil's Island

The penal colony of Cayenne ( French: ''Bagne de Cayenne''), commonly known as Devil's Island (''ĂŽle du Diable''), was a French penal colony that operated for 100 years, from 1852 to 1952, and officially closed in 1953, in the Salvation Islan ...

in French Guiana.

Lt. Col. Georges Picquart came across evidence that implicated another officer, Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy

Charles Marie Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy (16 December 1847 – 21 May 1923) was an officer in the French Army from 1870 to 1898. He gained notoriety as a spy for the German Empire and the actual perpetrator of the act of treason of which ...

, and informed his superiors. Rather than move to clear Dreyfus, the decision was made to protect Esterhazy and ensure the original verdict was not overturned. Major Hubert-Joseph Henry forged documents that made it seem as if Dreyfus were guilty, while Picquart was reassigned to duty in Africa. However, Picquart's findings were communicated by his lawyer to the Senator Auguste Scheurer-Kestner, who took up the case, at first discreetly and then increasingly publicly. Meanwhile, further evidence was brought forward by Dreyfus's family and Esterhazy's estranged family and creditors. Under pressure, the general staff arranged for a closed court-martial to be held on 10–11 January 1898, at which Esterhazy was tried ''in camera'' and acquitted. Picquart was detained on charges of violation of professional secrecy.

In response Zola risked his career and more, and on 13 January 1898 published '' J'Accuse...!'' /en.wikisource.org/wiki/J'accuse...!?match=fr J'accuse letterat French wikisource

Wikisource is an online wiki-based digital library of free-content source text, textual sources operated by the Wikimedia Foundation. Wikisource is the name of the project as a whole; it is also the name for each instance of that project, one f ...

on the front page of the Paris daily ''L'Aurore

; ) was a literary, liberal, and socialist newspaper published in Paris, France, from 1897 to 1914. Its most famous headline was Émile Zola's ''J'accuse...!'' leading into his article on the Dreyfus Affair.

The newspaper was published by Geo ...

''. The newspaper was run by Ernest Vaughan and Georges Clemenceau, who decided that the controversial story would be in the form of an open letter

An open letter is a Letter (message), letter that is intended to be read by a wide audience, or a letter intended for an individual, but that is nonetheless widely distributed intentionally.

Open letters usually take the form of a letter (mess ...

to the president, FĂ©lix Faure. Zola's ''J'Accuse...!'' accused the highest levels of the French Army of obstruction of justice and antisemitism

Antisemitism or Jew-hatred is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Whether antisemitism is considered a form of racism depends on the school of thought. Antisemi ...

by having wrongfully convicted Alfred Dreyfus to life imprisonment on Devil's Island

The penal colony of Cayenne ( French: ''Bagne de Cayenne''), commonly known as Devil's Island (''ĂŽle du Diable''), was a French penal colony that operated for 100 years, from 1852 to 1952, and officially closed in 1953, in the Salvation Islan ...

in French Guiana

French Guiana, or Guyane in French, is an Overseas departments and regions of France, overseas department and region of France located on the northern coast of South America in the Guianas and the West Indies. Bordered by Suriname to the west ...

. Zola's intention was that he be prosecuted for libel so that the new evidence in support of Dreyfus would be made public.

The case, known as the Dreyfus affair, deeply divided France between the reactionary army and Catholic Church on one hand, and the more liberal commercial society on the other. The ramifications continued for many years; on the 100th anniversary of Zola's article, France's Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

daily paper, '' La Croix'', apologised for its antisemitic editorials during the Dreyfus affair. As Zola was a leading French thinker and public figure, his letter formed a major turning point in the affair.

Zola was brought to trial for criminal libel on 7 February 1898, and was convicted on 23 February and removed from the Legion of Honour

The National Order of the Legion of Honour ( ), formerly the Imperial Order of the Legion of Honour (), is the highest and most prestigious French national order of merit, both military and Civil society, civil. Currently consisting of five cl ...

. The first judgment was overturned in April on a technicality, but a new suit was pressed against Zola, which opened on 18 July. At his lawyer's advice, Zola fled to England rather than wait for the end of the trial (at which he was again convicted). Without even having had the time to pack a few clothes, he arrived at Victoria Station on 19 July, the start of a brief and unhappy residence in the UK. Zola wrote a book about his exile in England: ''Pages d'exil'' (''Notes from Exile'').

Zola visited historic locations including a Church of England service at Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an Anglican church in the City of Westminster, London, England. Since 1066, it has been the location of the coronations of 40 English and British m ...

. After initially staying at the Grosvenor Hotel, Victoria, Zola went to the Oatlands Park Hotel in Weybridge

Weybridge () is a town in the Borough of Elmbridge, Elmbridge district in Surrey, England, around southwest of central London. The settlement is recorded as ''Waigebrugge'' and ''Weibrugge'' in the 7th century and the name derives from a cro ...

and shortly afterwards rented a house locally called Penn where he was joined by his family for the summer. At the end of August, they moved to another house in Addlestone

Addlestone ( or ) is a town in Surrey, England. It is located approximately southwest of London. The town is the administrative centre of the Runnymede (borough), Borough of Runnymede, of which it is the largest settlement.

Geography

Addlesto ...

called Summerfield. In early October the family moved to London and then his wife and children went back to France so the children could resume their schooling. Thereafter Zola lived alone in the Queen's Hotel, Norwood. He stayed in Upper Norwood

Upper Norwood is an area of south London, England, within the London Boroughs of London Borough of Bromley, Bromley, London Borough of Croydon, Croydon, London Borough of Lambeth, Lambeth and London Borough of Southwark, Southwark. It is north ...

from October 1898 to June 1899.

In France, the furious divisions over the Dreyfus affair continued. The fact of Major Henry's forgery was discovered and admitted to in August 1898, and the Government referred Dreyfus's original court-martial to the Supreme Court for review the following month, over the objections of the General Staff. Eight months later, on 3 June 1899, the Supreme Court annulled the original verdict and ordered a new military court-martial. The same month Zola returned from his exile in England. Still the anti-Dreyfusards would not give up, and on 9 September 1899 Dreyfus was again convicted.

Dreyfus applied for a retrial, but the government countered by offering Dreyfus a pardon (rather than exoneration), which would allow him to go free, provided that he admit to being guilty. Although he was clearly not guilty, he chose to accept the pardon. Later the same month, despite Zola's condemnation, an amnesty bill was passed, covering "all criminal acts or misdemeanours related to the Dreyfus affair or that have been included in a prosecution for one of these acts", indemnifying Zola and Picquart, but also all those who had concocted evidence against Dreyfus. Dreyfus was finally completely exonerated by the Supreme Court in 1906.

Zola said of the affair, "The truth is on the march, and nothing shall stop it." Zola's 1898 article is widely viewed in France as the most prominent manifestation of the new power of the intellectuals (writers, artists, academicians) in shaping public opinion

Public opinion, or popular opinion, is the collective opinion on a specific topic or voting intention relevant to society. It is the people's views on matters affecting them.

In the 21st century, public opinion is widely thought to be heavily ...

, the media and the state.

The Manifesto of the Five

On August 18, 1887, the French daily newspaper ''Le Figaro

() is a French daily morning newspaper founded in 1826. It was named after Figaro, a character in several plays by polymath Pierre Beaumarchais, Beaumarchais (1732–1799): ''Le Barbier de Séville'', ''The Guilty Mother, La Mère coupable'', ...

'' published "The Manifesto of the Five" shortly after '' La Terre'' was released. The signatories included Paul Bonnetain, J. H. Rosny, Lucien Descaves, Paul Margueritte and Gustave Guiches, who strongly disapproved of the lack of balance of both morals and aesthetics throughout the book's depiction of the revolution. The manifesto accused Zola of having "lowered the standard of Naturalism, of catering to large sales by deliberate obscenities, of being a morbid and impotent hypochondriac, incapable of taking a sane and healthy view of mankind. They freely referred to Zola's physiological weaknesses and expressed the utmost horror at the crudeness of La Terre."

Death

Zola died on 29 September 1902 of

Zola died on 29 September 1902 of carbon monoxide poisoning

Carbon monoxide poisoning typically occurs from breathing in carbon monoxide (CO) at excessive levels. Symptoms are often described as " flu-like" and commonly include headache, dizziness, weakness, vomiting, chest pain, and confusion. Large ...

caused by an improperly ventilated chimney. His funeral on 5 October was attended by thousands. Alfred Dreyfus initially had promised not to attend the funeral, but was given permission by Zola's widow and attended. At the time of his death Zola had just completed a novel, , about the Dreyfus trial. A sequel, , had been planned, but was not completed.

His enemies were blamed for his death because of previous attempts on his life, but nothing could be proven at the time. Expressions of sympathy arrived from everywhere in France; for a week the vestibule of his house was crowded with notable writers, scientists, artists, and politicians who came to inscribe their names in the registers. On the other hand, Zola's enemies used the opportunity to celebrate in malicious glee. Writing in '' L'Intransigeant'', Henri Rochefort claimed Zola had committed suicide, having discovered Dreyfus to be guilty.

Zola was initially buried in the Cimetière de Montmartre in Paris, but on 4 June 1908, just five years and nine months after his death, his remains were relocated to the Panthéon

The Panthéon (, ), is a monument in the 5th arrondissement of Paris, France. It stands in the Latin Quarter, Paris, Latin Quarter (Quartier latin), atop the , in the centre of the , which was named after it. The edifice was built between 1758 ...

, where he shares a crypt with Victor Hugo

Victor-Marie Hugo, vicomte Hugo (; 26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885) was a French Romanticism, Romantic author, poet, essayist, playwright, journalist, human rights activist and politician.

His most famous works are the novels ''The Hunchbac ...

and Alexandre Dumas

Alexandre Dumas (born Alexandre Dumas Davy de la Pailleterie, 24 July 1802 – 5 December 1870), also known as Alexandre Dumas , was a French novelist and playwright.

His works have been translated into many languages and he is one of the mos ...

. The ceremony was disrupted by an assassination attempt on Alfred Dreyfus

Alfred Dreyfus (9 October 1859 – 12 July 1935) was a French Army officer best known for his central role in the Dreyfus affair. In 1894, Dreyfus fell victim to a judicial conspiracy that eventually sparked a major political crisis in the Fre ...

by , a disgruntled journalist and admirer of Édouard Drumont, in which Dreyfus was wounded in the arm by the gunshot. Grégori was acquitted by the Parisian court which accepted his defense that he had not meant to kill Dreyfus, meaning merely to graze him.

A 1953 investigation by journalist Jean Bedel published in the newspaper ''Libération

(), popularly known as ''Libé'' (), is a daily newspaper in France, founded in Paris by Jean-Paul Sartre and Serge July in 1973 in the wake of the protest movements of May 1968 in France, May 1968. Initially positioned on the far left of Fr ...

'' under the headline "Was Zola assassinated?" raised the idea that Zola's death might have been a murder rather than an accident. It is based on the revelation by Norman pharmacist Pierre Hacquin, who was told by chimney-sweep Henri Buronfosse that he intentionally blocked the chimney of Zola's apartment in Paris.

Literary historian Alain Pagès believes that is likely true and Zola's great-granddaughters, Brigitte Émile-Zola and Martine Le Blond-Zola, corroborate this explanation of Zola's poisoning by carbon monoxide. As reported in '' L'Orient-Le Jour'', Brigitte Émile-Zola recounts that her grandfather Jacques Émile-Zola, son of Émile Zola, told her at the age of eight that, in 1952, a man came to his house to give him information about his father's death. The man had been with a dying friend, who had confessed to taking money to plug Emile Zola's chimney.

Scope of the Rougon-Macquart series

Zola's Rougon-Macquart novels are a panoramic account of theSecond French Empire

The Second French Empire, officially the French Empire, was the government of France from 1852 to 1870. It was established on 2 December 1852 by Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, president of France under the French Second Republic, who proclaimed hi ...

. They tell the story of a family approximately between the years 1851 and 1871. These twenty novels contain over 300 characters, who descend from the two family lines of the Rougons and Macquarts. In Zola's words, which are the subtitle of the Rougon-Macquart series, they are ''"L'Histoire naturelle et sociale d'une famille sous le Second Empire" ("The natural and social history of a family under the Second Empire").''

Most of the Rougon-Macquart novels were written during the French Third Republic

The French Third Republic (, sometimes written as ) was the system of government adopted in France from 4 September 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed during the Franco-Prussian War, until 10 July 1940, after the Fall of France durin ...

. To an extent, attitudes and value judgments may have been superimposed on that picture with the wisdom of hindsight. Some critics classify Zola's work, and naturalism more broadly, as a particular strain of decadent literature, which emphasized the fallen, corrupted state of modern civilization. Nowhere is the doom-laden image of the Second Empire so clearly seen as in '' Nana'', which culminates in echoes of the Franco-Prussian War

The Franco-Prussian War or Franco-German War, often referred to in France as the War of 1870, was a conflict between the Second French Empire and the North German Confederation led by the Kingdom of Prussia. Lasting from 19 July 1870 to 28 Janua ...

(and hence by implication of the French defeat). Even in novels dealing with earlier periods of Napoleon III's reign the picture of the Second Empire is sometimes overlaid with the imagery of catastrophe.

In the Rougon-Macquart novels, provincial life can seem to be overshadowed by Zola's preoccupation with the capital. However, the following novels (see the individual titles in the Livre de poche series) scarcely touch on life in Paris: '' La Terre'' (peasant life in Beauce), '' Le Rêve'' (an unnamed cathedral city), '' Germinal'' (collieries in the northeast of France), '' La Joie de vivre'' (the Atlantic coast), and the four novels set in and around Plassans (modelled on his childhood home, Aix-en-Provence), (, '' La Conquête de Plassans'', '' La Faute de l'Abbé Mouret'' and '' Le Docteur Pascal''). '' La Débâcle'', the military novel, is set for the most part in country districts of eastern France; its dénouement takes place in the capital during the civil war leading to the suppression of the

In the Rougon-Macquart novels, provincial life can seem to be overshadowed by Zola's preoccupation with the capital. However, the following novels (see the individual titles in the Livre de poche series) scarcely touch on life in Paris: '' La Terre'' (peasant life in Beauce), '' Le Rêve'' (an unnamed cathedral city), '' Germinal'' (collieries in the northeast of France), '' La Joie de vivre'' (the Atlantic coast), and the four novels set in and around Plassans (modelled on his childhood home, Aix-en-Provence), (, '' La Conquête de Plassans'', '' La Faute de l'Abbé Mouret'' and '' Le Docteur Pascal''). '' La Débâcle'', the military novel, is set for the most part in country districts of eastern France; its dénouement takes place in the capital during the civil war leading to the suppression of the Paris Commune

The Paris Commune (, ) was a French revolutionary government that seized power in Paris on 18 March 1871 and controlled parts of the city until 28 May 1871. During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, the French National Guard (France), Nation ...

. Though Paris has its role in the most striking incidents (notably the train crash) take place elsewhere. Even the Paris-centred novels tend to set some scenes outside, if not very far from, the capital. In the political novel '' Son Excellence Eugène Rougon'', the eponymous minister's interventions on behalf of his so-called friends, have their consequences elsewhere, and the reader is witness to some of them. Even Nana, one of Zola's characters most strongly associated with Paris, makes a brief and typically disastrous trip to the country.

Quasi-scientific purpose

In ''Le Roman expérimental'' and ''Les Romanciers naturalistes'', Zola expounded the purposes of the "naturalist" novel. The experimental novel was to serve as a vehicle for scientific experiment, analogous to the experiments conducted by Claude Bernard and expounded by him in ''Introduction à la médecine expérimentale''. Claude Bernard's experiments were in the field of clinicalphysiology

Physiology (; ) is the science, scientific study of function (biology), functions and mechanism (biology), mechanisms in a life, living system. As a branches of science, subdiscipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ syst ...

, those of the Naturalist writers (Zola being their leader) would be in the realm of psychology

Psychology is the scientific study of mind and behavior. Its subject matter includes the behavior of humans and nonhumans, both consciousness, conscious and Unconscious mind, unconscious phenomena, and mental processes such as thoughts, feel ...

influenced by the natural environment. Balzac, Zola claimed, had already investigated the psychology of lechery in an experimental manner, in the figure of Hector Hulot in '' La Cousine Bette''. Essential to Zola's concept of the experimental novel was dispassionate observation of the world, with all that it involved by way of meticulous documentation. To him, each novel should be based upon a dossier. With this aim, he visited the colliery of Anzin in northern France, in February 1884 when a strike was on; he visited La Beauce (for '' La Terre''), Sedan, Ardennes (for '' La Débâcle'') and travelled on the railway line between Paris and Le Havre

Le Havre is a major port city in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy (administrative region), Normandy region of northern France. It is situated on the right bank of the estuary of the Seine, river Seine on the English Channel, Channe ...

(when researching '' La BĂŞte humaine'').

Characterisation

Zola strongly claimed that Naturalist literature is an experimental analysis of human psychology. Considering this claim, many critics, such asGyörgy Lukács

György Lukács (born Bernát György Löwinger; ; ; 13 April 1885 – 4 June 1971) was a Hungarian Marxist philosopher, literary historian, literary critic, and Aesthetics, aesthetician. He was one of the founders of Western Marxism, an inter ...

, find Zola strangely poor at creating lifelike and memorable characters in the manner of Honoré de Balzac

Honoré de Balzac ( , more commonly ; ; born Honoré Balzac; 20 May 1799 – 18 August 1850) was a French novelist and playwright. The novel sequence ''La Comédie humaine'', which presents a panorama of post-Napoleonic French life, is ...

or Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English novelist, journalist, short story writer and Social criticism, social critic. He created some of literature's best-known fictional characters, and is regarded by ...

, despite his ability to evoke powerful crowd scenes. It was important to Zola that no character should appear ''larger than'' life; but the criticism that his characters are "cardboard" is substantially more damaging. Zola, by refusing to make any of his characters larger than life (if that is what he has indeed done), did not inhibit himself from also achieving verisimilitude

In philosophy, verisimilitude (or truthlikeness) is the notion that some propositions are closer to being true than other propositions. The problem of verisimilitude is the problem of articulating what it takes for one false theory to be close ...

.

Although Zola found it scientifically and artistically unjustifiable to create larger-than-life characters, his work presents some larger-than-life symbols which, like the mine Le Voreux in '' Germinal'', take on the nature of a surrogate human life. The mine, the still in '' L'Assommoir'' and the locomotive La Lison in '' La BĂŞte humaine'' impress the reader with the vivid reality of human beings. The great natural processes of seedtime and harvest, death and renewal in '' La Terre'' are instinct with a vitality which is not human but is the elemental energy of life. Human life is raised to the level of the mythical as the hammerblows of Titans

In Greek mythology, the Titans ( ; ) were the pre-Twelve Olympians, Olympian gods. According to the ''Theogony'' of Hesiod, they were the twelve children of the primordial parents Uranus (mythology), Uranus (Sky) and Gaia (Earth). The six male ...

are seemingly heard underground at Le Voreux, or as in '' La Faute de l'Abbé Mouret'', the walled park of Le Paradou encloses a re-enactment—and restatement—of the Book of Genesis

The Book of Genesis (from Greek language, Greek ; ; ) is the first book of the Hebrew Bible and the Christian Old Testament. Its Hebrew name is the same as its incipit, first word, (In the beginning (phrase), 'In the beginning'). Genesis purpor ...

.

Zola's optimism

In Zola there is the theorist and the writer, the poet, the scientist and the optimist – features that are basically joined in his own confession of

In Zola there is the theorist and the writer, the poet, the scientist and the optimist – features that are basically joined in his own confession of positivism

Positivism is a philosophical school that holds that all genuine knowledge is either true by definition or positivemeaning '' a posteriori'' facts derived by reason and logic from sensory experience.John J. Macionis, Linda M. Gerber, ''Soci ...

; later in his life, when he saw his own position turning into an anachronism, he would still style himself with irony and sadness over the lost cause as "an old and rugged Positivist".

The poet is the artist in words whose writing, as in the racecourse scene in '' Nana'' or in the descriptions of the laundry in '' L'Assommoir'' or in many passages of '' La Faute de l'Abbé Mouret'', '' Le Ventre de Paris'' and '' La Curée'', vies with the colourful impressionistic techniques of Claude Monet

Oscar-Claude Monet (, ; ; 14 November 1840 – 5 December 1926) was a French painter and founder of Impressionism painting who is seen as a key precursor to modernism, especially in his attempts to paint nature as he perceived it. During his ...

and Pierre-Auguste Renoir

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (; ; 25 February 1841 – 3 December 1919) was a French people, French artist who was a leading painter in the development of the Impressionism, Impressionist style. As a celebrator of beauty and especially femininity, fe ...

. The scientist is a believer in some measure of scientific determinism – not that this, despite his own words "devoid of free will" ("''dépourvus de libre arbitre''"), need always amount to a philosophical denial of free will

Free will is generally understood as the capacity or ability of people to (a) choice, choose between different possible courses of Action (philosophy), action, (b) exercise control over their actions in a way that is necessary for moral respon ...

. The creator of "''la littérature putride''", a term of abuse invented by an early critic of '' Thérèse Raquin'' (a novel which predates series), emphasizes the squalid aspects of the human environment and upon the seamy side of human nature.

The optimist is that other face of the scientific experimenter, the man with an unshakable belief in human progress. Zola bases his optimism on ''innéité'' and on the supposed capacity of the human race to make progress in a moral sense. ''Innéité'' is defined by Zola as that process in which "''se confondent les caractères physiques et moraux des parents, sans que rien d'eux semble s'y retrouver''"; it is the term used in biology to describe the process whereby the moral and temperamental dispositions of some individuals are unaffected by the hereditary transmission of genetic characteristics. Jean Macquart and Pascal Rougon are two instances of individuals liberated from the blemishes of their ancestors by the operation of the process of ''innéité''.

In popular culture

* '' The Life of Émile Zola'' (1937) is a well-received film biography, starring Paul Muni, which devotes significant footage to Zola's involvement in exonerating Dreyfus. The film won the Academy Award for Outstanding Production. * Giannis Argyris played the role of Zola in theGreek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

melodrama ' (translitteration: Ime Athoos, "I am innocent", 1960) directed by Dinos Katsouridis.

* Zola is known to have been an inspiration to Christopher Hitchens

Christopher Eric Hitchens (13 April 1949 – 15 December 2011) was a British and American author and journalist. He was the author of Christopher Hitchens bibliography, 18 books on faith, religion, culture, politics, and literature. He was born ...

as found in his book '' Letters to a Young Contrarian'' (2001).

* The 2012 BBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is a British public service broadcaster headquartered at Broadcasting House in London, England. Originally established in 1922 as the British Broadcasting Company, it evolved into its current sta ...

TV series '' The Paradise'' is based on Zola's 1883 novel '' Au Bonheur des Dames''.

* '' Cézanne et Moi'' (2016) is a French film, directed by Danièle Thompson, that explores the friendship between Zola and the Post-Impressionist painter Paul Cézanne

Paul Cézanne ( , , ; ; ; 19 January 1839 – 22 October 1906) was a French Post-Impressionism, Post-Impressionist painter whose work introduced new modes of representation, influenced avant-garde artistic movements of the early 20th century a ...

.

Bibliography

French language

* ''La Confession de Claude'' (1865) * '' Les Mystères de Marseille'' (1867) * '' Thérèse Raquin'' (1867) * '' Madeleine Férat'' (1868) * ''Nouveaux Contes à Ninon'' (1874) * ''Le Roman Experimental'' (1880) * ''Jacques Damour et autres nouvelles'' (1880) * ''L'Attaque du moulin'' (1877), short story included in '' Les Soirées de Médan'' * '' L'Inondation'' (''The Flood'') novella (1880) * ** (1871) ** '' La Curée'' (1871–72) ** '' Le Ventre de Paris'' (1873) ** '' La Conquête de Plassans'' (1874) ** '' La Faute de l'Abbé Mouret'' (1875) ** '' Son Excellence Eugène Rougon'' (1876) ** '' L'Assommoir'' (1877) ** '' Une page d'amour'' (1878) ** '' Nana'' (1880) ** '' Pot-Bouille'' (1882) ** '' Au Bonheur des Dames'' (1883) ** '' La joie de vivre'' (1884) ** '' Germinal'' (1885) ** '' L'Œuvre'' (1886) ** '' La Terre'' (1887) ** '' Le Rêve'' (1888) ** '' La Bête humaine'' (1890) ** '' L'Argent'' (1891) ** '' La Débâcle'' (1892) ** '' Le Docteur Pascal'' (1893) * ''Les Trois Villes'' ** ''Lourdes'' (1894) ** ''Rome'' (1896) ** ''Paris'' (1898) * ''Les Quatre Évangiles'' ** ''Fécondité'' (1899) ** ''Travail'' (1901) ** ''Vérité'' (1903, published posthumously) ** ''Justice'' (unfinished)Works translated into English

'' The Three Cities'' # ''Lourdes'' (1894) # ''Rome'' (1896) # ''Paris'' (1898) ''The Four Gospels'' # ''Fruitfulness'' (1900) # ''Work'' (1901) # ''Truth'' (1903) # ''Justice'' (Unfinished) Standalones * ''The Mysteries of Marseilles'' (1895) * ''The FĂŞte at Coqueville'' (1907)Modern translations

* '' Madeleine Férat'' (1957) * '' Thérèse Raquin'' (1992, 1995, and 2013) * '' The Flood'' (2013) '' The Rougon-Macquart'' (1993–2021) # '' The Fortune of the Rougons'' (2012) # '' His Excellency Eugène Rougon'' (2018) # ''The Kill

"The Kill" (written "The Kill (Bury Me)" on the single and music video) is a song by American band Thirty Seconds to Mars. The song was released on January 24, 2006 as the second single from their second album, ''A Beautiful Lie''. It was certi ...

'' (2004)

# ''Money

Money is any item or verifiable record that is generally accepted as payment for goods and services and repayment of debts, such as taxes, in a particular country or socio-economic context. The primary functions which distinguish money are: m ...

'' (2016)

# '' The Dream'' (2018)

# '' The Conquest of Plassans'' (2014)

# '' Pot Luck'' (1999)

# '' The Ladies Paradise/The Ladies' Delight'' (1995, 2001)

# '' The Sin of Father Mouret'' (2017)

# '' A Love Story'' (2017)

# '' The Belly of Paris'' (2007)

# '' The Bright Side of Life'' (2018)

# '' The Drinking Den'' (2000, 2021)

# '' The Masterpiece'' (1993)

# '' The Beast Within'' (1999)

# '' Germinal'' (2004)

# '' Nana'' (2020)

# '' The Earth'' (2016)

# '' The Debacle'' (2000)

# '' Doctor Pascal'' (2020)

See also

*List of unsolved deaths

This list of unsolved deaths includes notable cases where:

* The cause of death could not be officially determined following an investigation

* The person's identity could not be established after they were found dead

* The cause is known, but th ...

References

Further reading

* * * * Harrow, Susan (2010). ''Zola, the Body Modern: Pressures and Prospects of Representation.'' Legenda: London. . OCLC 9781906540760 * * King, Graham (1978). ''Garden of Zola: Emile Zola and his Novels for English Readers''. London: Barrie & Jenkins. * * * * * * Richardson, Joanna (1978). ''Zola''. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. * Rosen, Michael (2017). ''The Disappearance of Émile Zola: Love, Literature and the Dreyfus Case''. London: Faber & Faber. . * *External links

* * * *Émile Zola Collection

at the

Harry Ransom Center

The Harry Ransom Center, known as the Humanities Research Center until 1983, is an archive, library, and museum at the University of Texas at Austin, specializing in the collection of literary and cultural artifacts from the Americas and Europe ...

*

*

Life of Émile Zola on NotreProvence.fr

Émile Zola at InterText Digital Library

Émile Zola at Livres & Ebooks

Émile Zola exhibition

at the

Bibliothèque nationale de France

The (; BnF) is the national library of France, located in Paris on two main sites, ''Richelieu'' and ''François-Mitterrand''. It is the national repository of all that is published in France. Some of its extensive collections, including bo ...

Lorgues, Plassans

Livres audio gratuits pour Émile Zola

*

Works about Émile Zola

at the

Internet Archive

The Internet Archive is an American 501(c)(3) organization, non-profit organization founded in 1996 by Brewster Kahle that runs a digital library website, archive.org. It provides free access to collections of digitized media including web ...

References to Émile Zola in historic European newspapers

Emile Zola Writes a Letter to Alfred Dreyfus at the Height of the Dreyfus Affair

{{DEFAULTSORT:Zola, Emile 1840 births 1902 deaths Naturalized citizens of France 19th-century French dramatists and playwrights 19th-century French journalists 19th-century French male writers 19th-century French novelists 20th-century French male writers 20th-century French novelists Accidental deaths in France Burials at Montmartre Cemetery Burials at the Panthéon, Paris Deaths from carbon monoxide poisoning Dreyfusards French male novelists French male journalists French people of Italian descent French people of Greek descent French psychological fiction writers Lycée Saint-Louis alumni People from Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur People of Venetian descent Unsolved deaths in France Writers from Paris French literary critics French literary theorists 19th-century French photographers 19th-century French short story writers French male short story writers 19th-century French essayists French art critics French librettists