|

Taotie

The ''Taotie'' () is an ancient Chinese mythological creature that was commonly emblazoned on bronze and other artifacts during the 1st millennium BC. ''Taotie'' are one of the " four evil creatures of the world". In Chinese classical texts such as the "Classic of Mountains and Seas", the fiend is named alongside the ''Hundun'' (), ''Qiongqi'' () and ''Taowu'' (). They are opposed by the Four Holy Creatures, the Azure Dragon, Vermilion Bird, White Tiger and Black Tortoise. The four fiends are also juxtaposed with the four benevolent animals which are Qilin (), Dragon (), Turtle () and Fenghuang (). The ''Taotie'' is often represented as a motif on '' dings'', which are Chinese ritual bronze vessels from the Shang (1766-1046 BCE) and Zhou dynasties (1046–256 BCE). The design typically consists of a zoomorphic mask, described as being frontal, bilaterally symmetrical, with a pair of raised eyes and typically no lower jaw area. Some argue that the design can be traced bac ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Four Perils

The Four Perils () are four malevolent beings that existed in Chinese mythology and the antagonistic counterparts of the Four Benevolent Animals. ''Book of Documents'' In the ''Book of Documents'', they are defined as the "Four Criminals" (): * Gonggong (, the disastrous god; * Huandou (, a.k.a. , ), a chimeric minister and/or nation from the south who conspired with Gonggong against Emperor Yao * Gun (), father of Yu the Great whose poorly-built dam released a destructive flood; * Sanmiao (), the tribes that attacked Emperor Yao's tribe. ''Zuo Zhuan'', ''Shanhaijing'', and ''Shenyijing'' In Zuo Zhuan, ''Shanhaijing'', and '' Shenyijing'', the Four Perils (Hanzi: 四凶; pinyin: Sì Xiōng) are defined as: * the Hundun (, ), a yellow winged creature of chaos with six legs and no face; * the Qiongqi (), a monstrous creature that eats people, considered the same in Japan as Kamaitachi; * the Taowu (), a reckless, stubborn creature; * the Taotie (), a gluttonous beast. Ident ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Chinese Ritual Bronzes

Sets and individual examples of ritual bronzes survive from when they were made mainly during the Chinese Bronze Age. Ritual bronzes create quite an impression both due to their sophistication of design and manufacturing process, but also because of their remarkable durability. From around 1650 BCE, these elaborately decorated vessels were deposited as grave goods in the tombs of royalty and the nobility, and were evidently produced in very large numbers, with documented excavations finding over 200 pieces in a single royal tomb. They were produced for an individual or social group to use in making ritual offerings of food and drink to his or their ancestors and other deities or spirits. Such ceremonies generally took place in family temples or ceremonial halls over tombs. These ceremonies can be seen as ritual banquets in which both living and dead members of a family were supposed to participate. Details of these ritual ceremonies are preserved through early literary record ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Hundun

Hundun () is both a "legendary faceless being" in Chinese mythology and the "primordial and central chaos" in Chinese cosmogony, comparable with the world egg. Linguistics ''Hundun'' was semantically extended from a mythic "primordial chaos; nebulous state of the universe before heaven and earth separated" to mean "unintelligible; chaotic; messy; mentally dense; innocent as a child". While ''hùndùn'' "primordial chaos" is usually written as in contemporary vernacular, it is also written as —as in the Daoist classic '' Zhuangzi''—or —as in the '' Zuozhuan''. ''Hùn'' "chaos; muddled; confused" is written either ''hùn'' () or ''hún'' (). These two are interchangeable graphic variants read as ''hún'' ( ) and ''hùn'' "nebulous; stupid" (''hùndùn'' ). ''Dùn'' ("dull; confused") is written as either ''dùn'' () or ''dūn'' (). Isabelle Robinet outlines the etymological origins of ''hundun''. Semantically, the term ''hundun'' is related to several expressions, ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Ding (vessel)

''Ding'' () are prehistoric and ancient Chinese cauldrons, standing upon legs with a lid and two facing handles. They are one of the most important shapes used in Chinese ritual bronzes. They were made in two shapes: round vessels with three legs and rectangular ones with four, the latter often called ''fangding''. They were used for cooking, storage, and ritual offerings to the gods or to ancestors. The earliest recovered examples are pre-Shang ceramic ding at the Erlitou site but they are better known from the Bronze Age, particularly after the Zhou deemphasized the ritual use of wine practiced by the Shang kings. Under the Zhou, the ding and the privilege to perform the associated rituals became symbols of authority. The number of permitted ding varied according to one's rank in the Chinese nobility: the Nine Ding of the Zhou kings were a symbol of their rule over all China but were lost by the first emperor, Shi Huangdi in the late 3rd century BCE. [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Fenghuang

''Fènghuáng'' (, ) are mythological birds found in Sinospheric mythology that reign over all other birds. The males were originally called ''fèng'' and the females ''huáng'', but such a distinction of gender is often no longer made and they are blurred into a single feminine entity so that the bird can be paired with the Chinese dragon, which is traditionally deemed male. It is known under similar names in various other languages ( Japanese: ; vi, phượng hoàng, italics=no or ; Korean: ). In the Western world, it is commonly called the Chinese phoenix or simply phoenix, although mythological similarities with the Western phoenix are superficial. Appearance A common depiction of fenghuang was of it attacking snakes with its talons and its wings spread. According to the ''Erya'''s chapter 17 ''Shiniao'', fenghuang is made up of the beak of a rooster, the face of a swallow, the forehead of a fowl, the neck of a snake, the breast of a goose, the back of a tortoise ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Sarah Allan

Sarah Allan (; born 1945) is an American paleographer and scholar of ancient China. She was a Burlington Northern Foundation Professor of Asian Studies in the Department of Asian and Middle Eastern Languages and Literatures at Dartmouth College; she is currently affiliated to the University of California, Berkeley. She is Chair for the Society for the Study of Early China and Editor of Early China. Previously, she was Senior Lecturer in Chinese at the School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London. She is best known for her interdisciplinary approach to the mythological and philosophical systems of early Chinese civilization. Biography Allan received a B.A. degree in 1966 from the University of California, Los Angeles, and her M.A. and Ph.D. degrees in 1969 and 1974 respectively from the University of California, Berkeley. At UCLA, she studied archaeology with Richard C. Rudolph and took a course in Chinese art history with J. Leroy Davidson, and she studied ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

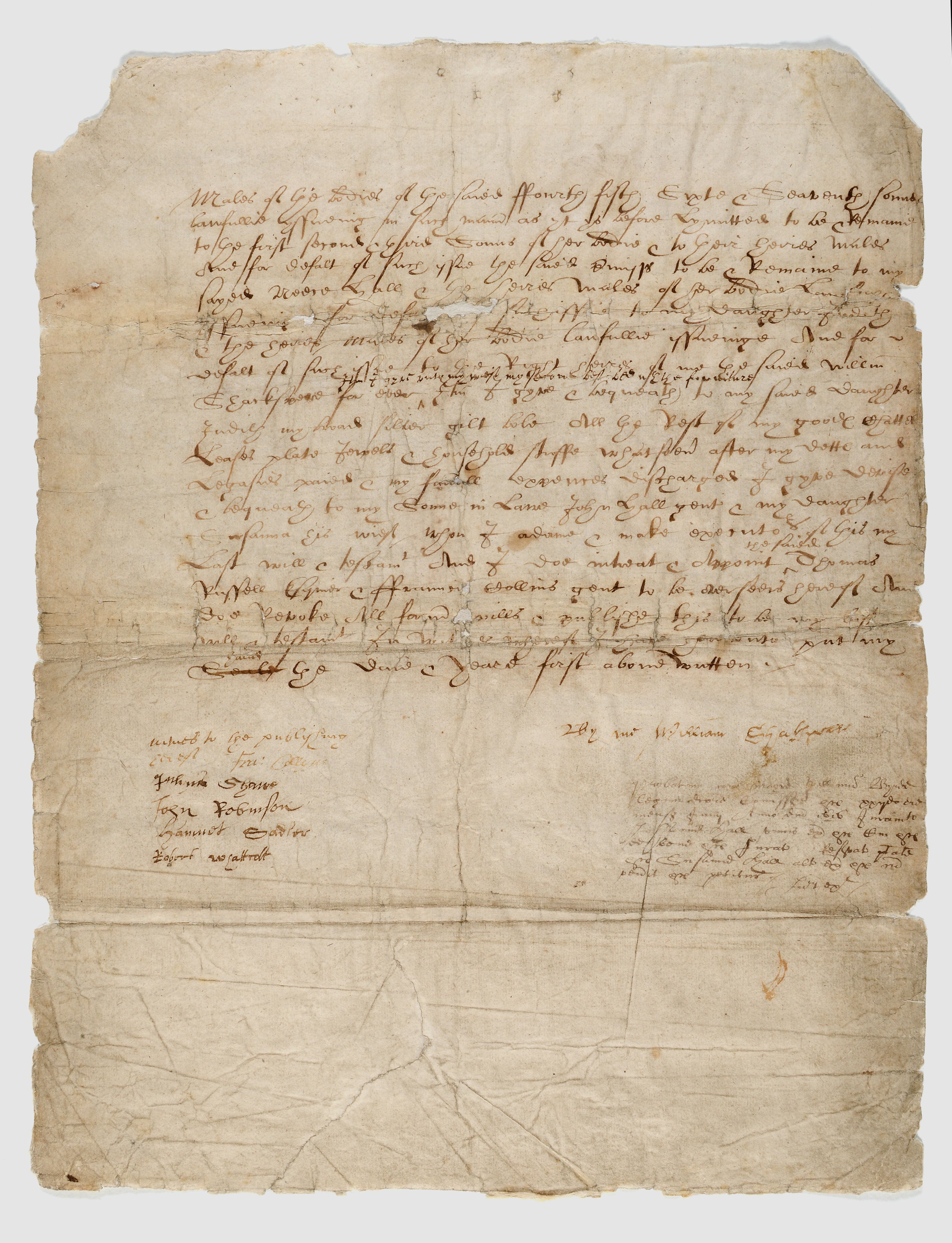

Palaeographer

Palaeography ( UK) or paleography ( US; ultimately from grc-gre, , ''palaiós'', "old", and , ''gráphein'', "to write") is the study of historic writing systems and the deciphering and dating of historical manuscripts, including the analysis of historic handwriting. It is concerned with the forms and processes of writing; not the textual content of documents. Included in the discipline is the practice of deciphering, reading, and dating manuscripts, and the cultural context of writing, including the methods with which writing and books were produced, and the history of scriptoria. The discipline is one of the auxiliary sciences of history. It is important for understanding, authenticating, and dating historic texts. However, it generally cannot be used to pinpoint dates with high precision. Application Palaeography can be an essential skill for historians and philologists, as it tackles two main difficulties. First, since the style of a single alphabet in each given la ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Tripod For Food (Ding), For Rituals Celebrating The Ancestors

A tripod is a portable three-legged frame or stand, used as a platform for supporting the weight and maintaining the stability of some other object. The three-legged (triangular stance) design provides good stability against gravitational loads as well as horizontal shear forces, and better leverage for resisting tipping over due to lateral forces can be achieved by spreading the legs away from the vertical centre. Variations with one, two, and four legs are termed ''monopod'', ''bipod'', and ''quadripod'' (similar to a table). Etymology First attested in English in the early 17th century, the word ''tripod'' comes via Latin ''tripodis'' (GEN of ''tripus''), which is the romanization of Greek (''tripous''), "three-footed" (GEN , ''tripodos''), ultimately from (''tri-''), "three times" (from , ''tria'', "three") + (''pous''), "foot". The earliest attested form of the word is the Mycenaean Greek , ''ti-ri-po'', written in Linear B syllabic script. Cultural use Many cult ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Lower Xiajiadian Culture

The Lower Xiajiadian culture (; 2200–1600 BC) is an archaeological culture in Northeast China, found mainly in southeastern Inner Mongolia, northern Hebei, and western Liaoning, China. Subsistence was based on millet farming supplemented with animal husbandry and hunting. Archaeological sites have yielded the remains of pigs, dogs, sheep, and cattle. The culture built permanent settlements and achieved relatively high population densities. The population levels reached by the Lower Xiajiadian culture in the Chifeng region would not be matched until the Liao Dynasty. The culture was preceded by the Hongshan culture, through the transitional Xiaoheyan culture. The type site is represented by the lower layer at Xiajiadian in Chifeng, Inner Mongolia. According to a 2011 study published in the ''Journal of Human Genetics'', "the West Liao River Valley was a contact zone between northern steppe tribes and the Central Plain farming population. The formation and development of th ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Liangzhu Culture

The Liangzhu culture (; 3300–2300 BC) was the last Neolithic jade culture in the Yangtze River Delta of China. The culture was highly stratified, as jade, silk, ivory and lacquer artifacts were found exclusively in elite burials, while pottery was more commonly found in the burial plots of poorer individuals. This division of class indicates that the Liangzhu period was an early state, symbolized by the clear distinction drawn between social classes in funeral structures. A pan-regional urban center had emerged at the Liangzhu city-site and elite groups from this site presided over the local centers. The Liangzhu culture was extremely influential and its sphere of influence reached as far north as Shanxi and as far south as Guangdong. The primary Liangzhu site was perhaps among the oldest Neolithic sites in East Asia that would be considered a state society. The type site at Liangzhu was discovered in Yuhang County, Zhejiang and initially excavated by Shi Xingeng in 1936. On 6 ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Zoomorphic

The word ''zoomorphism'' derives from the Greek ζωον (''zōon''), meaning "animal", and μορφη (''morphē''), meaning "shape" or "form". In the context of art, zoomorphism could describe art that imagines humans as non-human animals. It can also be defined as art that portrays one species of animal like another species of animal or art that uses animals as a visual motif, sometimes referred to as "animal style." In ancient Egyptian religion, deities were depicted in animal form which is an example of zoomorphism in not only art but in a religious context. It is also similar to the term therianthropy; which is the ability to shape shift into animal form, except that with zoomorphism the animal form is applied to a physical object. It means to attribute animal forms or animal characteristics to other animals, or things other than an animal; similar to but broader than anthropomorphism. Contrary to anthropomorphism, which views animal or non-animal behavior in human terms, zo ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

_with_human_faces_02.jpg)