|

S. Pombe

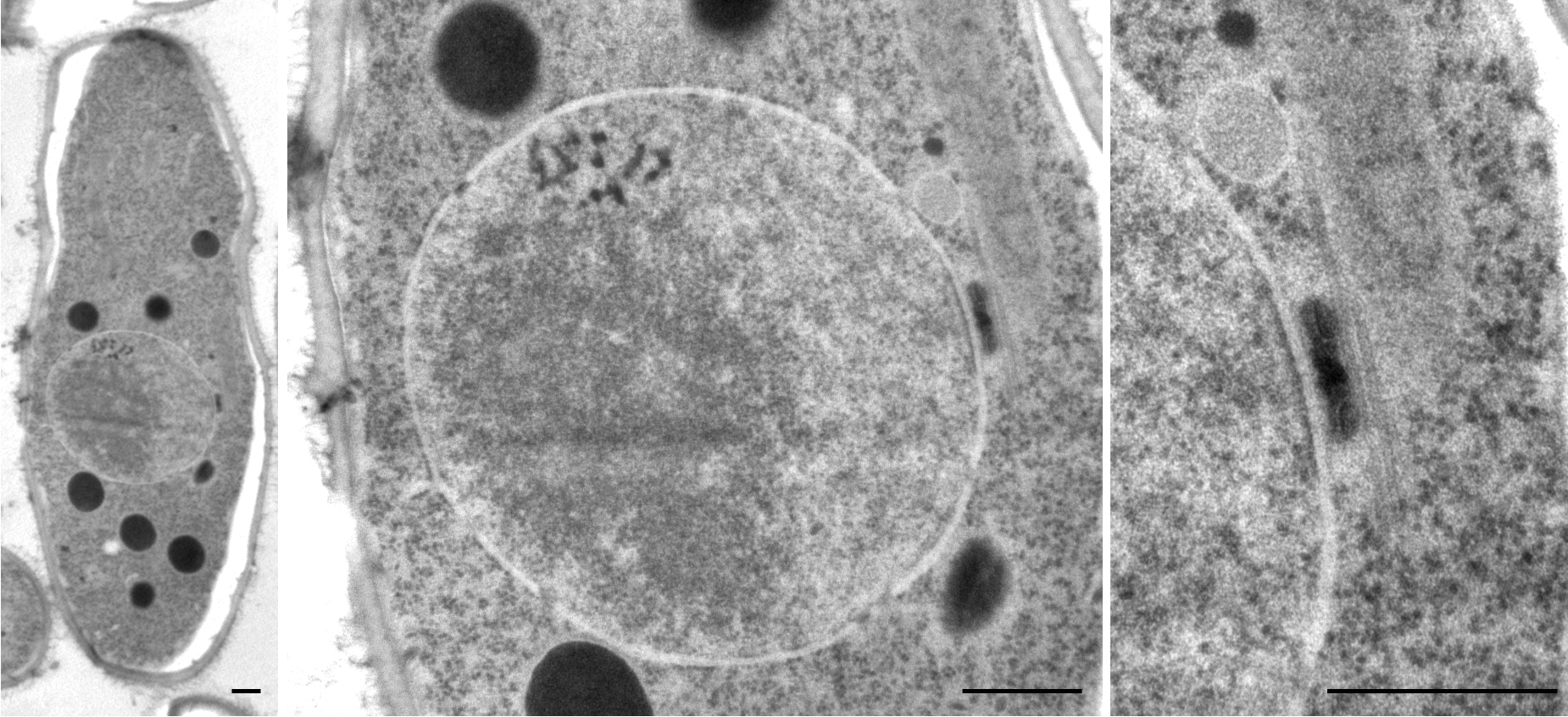

''Schizosaccharomyces pombe'', also called "fission yeast", is a species of yeast used in traditional brewing and as a model organism in molecular and cell biology. It is a unicellular eukaryote, whose cells are rod-shaped. Cells typically measure 3 to 4 micrometres in diameter and 7 to 14 micrometres in length. Its genome, which is approximately 14.1 million base pairs, is estimated to contain 4,970 protein-coding genes and at least 450 non-coding RNAs. These cells maintain their shape by growing exclusively through the cell tips and divide by medial fission to produce two daughter cells of equal size, which makes them a powerful tool in cell cycle research. Fission yeast was isolated in 1893 by Paul Lindner from East African millet beer. The species name ''pombe'' is the Swahili word for beer. It was first developed as an experimental model in the 1950s: by Urs Leupold for studying genetics, and by Murdoch Mitchison for studying the cell cycle. Paul Nurse, a fission yea ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Paul Lindner

Paul Lindner (1861 – 1945) was a German chemist and microbiologist, best known for discovering the fission yeast ''Schizosaccharomyces pombe''. Biography and career Lindner was born in 1861 in Giesmannsdorf near the Neisse River, part of Upper Silesia. He was a chemist, biologist, and microbiologist. While conducting research, he served as a professor at the Agricultural University of Berlin's Institute of Fermentation and Starch Production. In 1893, Lindner discovered the ''Schizosaccharomyces pombe'' (''S. pombe'') species of yeast by isolating it from samples of Bantu beer, a type of East African millet beer. The beer had been sent to Germany in 1890 by Major Hermann von Wissmann, and upon arrival, it was prepared as a pure culture (only the one strain being present). Lindner named the strain after the Swahili word for beer, "pombe". The original isolate strain Lindner identified in 1893 was homothallic, and it consisted of both + and – mating type cells. This str ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Murdoch Mitchison

John Murdoch Mitchison (11 June 1922, Oxford – 17 March 2011, Edinburgh) was a British zoologist. Background Family Mitchison was the son of the Labour politician Dick Mitchison and his wife, the writer Naomi (née Haldane). The biologist J.B.S. Haldane was his uncle, and the physiologist John Scott Haldane was his maternal grandfather. His elder brother is the bacteriologist Denis Mitchison, and his younger brother is the zoologist Avrion Mitchison. His wife was the historian Rosalind Mitchison. Education Mitchison went to Winchester College and Trinity College, Cambridge, later becoming Professor of Zoology at Edinburgh University in 1963 after working there for a decade. He was elected a fellow of the Royal Society of London in 1978. Career Considered a pioneer in the area of cellular biology, Mitchison developed the yeast ''Schizosaccharomyces pombe'' as a model system to study the mechanisms and kinetics of growth and the cell cycle. He was an academic adviso ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Grapes

A grape is a fruit, botanically a berry, of the deciduous woody vines of the flowering plant genus ''Vitis''. Grapes are a non- climacteric type of fruit, generally occurring in clusters. The cultivation of grapes began approximately 8,000 years ago, and the fruit has been used as human food throughout its history. Eaten fresh or in dried form (as raisins, currants and sultanas), grapes also hold cultural significance in many parts of the world, particularly for their role in winemaking. Other grape-derived products include various types of jam, juice, vinegar and oil. History The Middle East is generally described as the homeland of grapes and the cultivation of this plant began there 6,000–8,000 years ago. Yeast, one of the earliest domesticated microorganisms, occurs naturally on the skins of grapes, leading to the discovery of alcoholic drinks such as wine. The earliest archeological evidence for a dominant position of wine-making in human culture dates from ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Apples

An apple is a round, edible fruit produced by an apple tree (''Malus'' spp.). Fruit trees of the orchard or domestic apple (''Malus domestica''), the most widely grown in the genus, are agriculture, cultivated worldwide. The tree originated in Central Asia, where its wild ancestor, ''Malus sieversii'', is still found. Apples have been grown for thousands of years in Eurasia before they were introduced to North America by European colonization of the Americas, European colonists. Apples have cultural significance in many mythological, mythologies (including Norse mythology, Norse and Greek mythology, Greek) and religions (such as Christianity in Europe). Apples grown from seeds tend to be very different from those of their parents, and the resultant fruit frequently lacks desired characteristics. For commercial purposes, including botanical evaluation, apple cultivars are propagated by clonal grafting onto rootstocks. Apple trees grown without rootstocks tend to be larger and ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

DNA Replication

In molecular biology, DNA replication is the biological process of producing two identical replicas of DNA from one original DNA molecule. DNA replication occurs in all life, living organisms, acting as the most essential part of heredity, biological inheritance. This is essential for cell division during growth and repair of damaged tissues, while it also ensures that each of the new cells receives its own copy of the DNA. The cell possesses the distinctive property of division, which makes replication of DNA essential. DNA is made up of a nucleic acid double helix, double helix of two Complementary DNA, complementary DNA strand, strands. DNA is often called double helix. The double helix describes the appearance of a double-stranded DNA which is composed of two linear strands that run opposite to each other and twist together. During replication, these strands are separated. Each strand of the original DNA molecule then serves as a template for the production of its counterpart, ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

DNA Damage

DNA repair is a collection of processes by which a cell identifies and corrects damage to the DNA molecules that encode its genome. A weakened capacity for DNA repair is a risk factor for the development of cancer. DNA is constantly modified in cells, by internal metabolic by-products, and by external ionizing radiation, ultraviolet light, and medicines, resulting in spontaneous DNA damage involving tens of thousands of individual molecular lesions per cell per day. DNA modifications can also be programmed. Molecular lesions can cause structural damage to the DNA molecule, and can alter or eliminate the cell's ability for transcription and gene expression. Other lesions may induce potentially harmful mutations in the cell's genome, which affect the survival of its daughter cells following mitosis. Consequently, DNA repair as part of the DNA damage response (DDR) is constantly active. When normal repair processes fail, including apoptosis, irreparable DNA damage may occur ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Green Fluorescent Protein

The green fluorescent protein (GFP) is a protein that exhibits green fluorescence when exposed to light in the blue to ultraviolet range. The label ''GFP'' traditionally refers to the protein first isolated from the jellyfish ''Aequorea victoria'' and is sometimes called ''avGFP''. However, GFPs have been found in other organisms including corals, sea anemones, zoanithids, copepods and lancelets. The GFP from ''A. victoria'' has a major excitation peak at a wavelength of 395 nm and a minor one at 475 nm. Its emission peak is at 509 nm, which is in the lower green portion of the visible spectrum. The fluorescence quantum yield (QY) of GFP is 0.79. The GFP from the sea pansy ('' Renilla reniformis'') has a single major excitation peak at 498 nm. GFP makes for an excellent tool in many forms of biology due to its ability to form an internal chromophore without requiring any accessory cofactors, gene products, or enzymes / substrates other than molecular ox ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Model Organism Database

Model organism databases (MODs) are biological databases, or knowledgebases, dedicated to the provision of in-depth biological data for intensively studied model organisms A model organism is a non-human species that is extensively studied to understand particular biological phenomena, with the expectation that discoveries made in the model organism will provide insight into the workings of other organisms. Mo .... MODs allow researchers to easily find background information on large sets of genes, efficiently plan experiments, integrate their data with existing knowledge, and formulate new hypotheses . They allow users to analyse results and interpret datasets, and the data they generate are increasingly used to describe less well studied species. Where possible, MODs share common approaches to collect and represent biological information. For example, all MODs use the Gene Ontology (GO) to describe functions, processes and cellular locations of specific gene products. P ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

PomBase

PomBase is a model organism database that provides online access to the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe genome sequence and annotated features, together with a wide range of manually curated functional gene-specific data. The PomBase website was redeveloped in 2016 to provide users with a more fully integrated, better-performing service (described in ). Data Curation and Quality Control PomBase staff manually curate a wide variety of data types using both primary literature and bioinformatics sources, and numerous mechanisms are employed to ensure both syntactical and biological content validity. Types of data curated include: * Genome sequence and features (e.g. physical location of genes in the genome) * Protein and ncRNA functions, the cellular processes they participate in and where they localize * Phenotypes associated with different alleles and genotypes * Specific protein modification sites and when they occur * Human and budding yeast orthologs of ''S. pombe ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Sequenced

In genetics and biochemistry, sequencing means to determine the primary structure (sometimes incorrectly called the primary sequence) of an unbranched biopolymer. Sequencing results in a symbolic linear depiction known as a sequence which succinctly summarizes much of the atomic-level structure of the sequenced molecule. DNA sequencing DNA sequencing is the process of determining the nucleotide order of a given DNA fragment. So far, most DNA sequencing has been performed using the chain termination method developed by Frederick Sanger. This technique uses sequence-specific termination of a DNA synthesis reaction using modified nucleotide substrates. However, new sequencing technologies such as pyrosequencing are gaining an increasing share of the sequencing market. More genome data are now being produced by pyrosequencing than Sanger DNA sequencing. Pyrosequencing has enabled rapid genome sequencing. Bacterial genomes can be sequenced in a single run with several times coverag ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Sanger Institute

The Wellcome Sanger Institute, previously known as The Sanger Centre and Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, is a non-profit organisation, non-profit British genomics and genetics research institute, primarily funded by the Wellcome Trust. It is located on the Wellcome Genome Campus by the village of Hinxton, outside Cambridge. It shares this location with the European Bioinformatics Institute. It was established in 1992 and named after double Nobel laureate Frederick Sanger. It was conceived as a large scale DNA sequencing centre to participate in the Human Genome Project, and went on to make the largest single contribution to the gold standard sequence of the human genome. From its inception the institute established and has maintained a policy of data sharing, and does much of its research in collaboration. Since 2000, the institute expanded its mission to understand "the role of genetics in health and disease". The institute now employs around 900 people and engages in five mai ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Nobel Prize In Physiology Or Medicine

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine () is awarded yearly by the Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute for outstanding discoveries in physiology or medicine. The Nobel Prize is not a single prize, but five separate prizes that, according to Alfred Nobel's 1895 will, are awarded "to those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind". Nobel Prizes are awarded in the fields of Physics, Medicine or Physiology, Chemistry, Literature, and Peace. The Nobel Prize is presented annually on the anniversary of Alfred Nobel's death, 10 December. As of 2024, 115 Nobel Prizes in Physiology or Medicine have been awarded to 229 laureates, 216 men and 13 women. The first one was awarded in 1901 to the German physiologist, Emil von Behring, for his work on serum therapy and the development of a vaccine against diphtheria. The first woman to receive the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, Gerty Cori, received it in 1947 for her role in elucida ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |