|

Problem Of Future Contingents

Future contingent propositions (or simply, future contingents) are statements about states of affairs in the future that are '' contingent:'' neither necessarily true nor necessarily false. The problem of future contingents seems to have been first discussed by Aristotle in chapter 9 of his ''On Interpretation'' (''De Interpretatione''), using the famous sea-battle example. Roughly a generation later, Diodorus Cronus from the Megarian school of philosophy stated a version of the problem in his notorious '' master argument''. The problem was later discussed by Leibniz. The problem can be expressed as follows. Suppose that a sea-battle will not be fought tomorrow. Then it was also true yesterday (and the week before, and last year) that it will not be fought, since any true statement about what will be the case in the future was also true in the past. But all past truths are now necessary truths; therefore it is now necessarily true in the past, prior and up to the original stat ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Miracle

A miracle is an event that is inexplicable by natural or scientific lawsOne dictionary define"Miracle"as: "A surprising and welcome event that is not explicable by natural or scientific laws and is therefore considered to be the work of a divine agency." and accordingly gets attributed to some supernatural or praeternatural cause. Various religions often attribute a phenomenon characterized as miraculous to the actions of a supernatural being, (especially) a deity, a miracle worker, a saint, or a religious leader. Informally, English-speakers often use the word ''miracle'' to characterise any beneficial event that is statistically unlikely but not contrary to the laws of nature, such as surviving a natural disaster, or simply a "wonderful" occurrence, regardless of likelihood (e.g. "the miracle of childbirth"). Some coincidences may be seen as miracles. A true miracle would, by definition, be a non-natural phenomenon, leading many writers to dismiss miracles as physically i ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Jan Łukasiewicz

Jan Łukasiewicz (; 21 December 1878 – 13 February 1956) was a Polish logician and philosopher who is best known for Polish notation and Łukasiewicz logic. His work centred on philosophical logic, mathematical logic and history of logic. He thought innovatively about traditional propositional logic, the principle of non-contradiction and the law of excluded middle, offering one of the earliest systems of many-valued logic. Contemporary research on Aristotelian logic also builds on innovative works by Łukasiewicz, which applied methods from modern logic to the formalization of Aristotle's syllogistic. The Łukasiewicz approach was reinvigorated in the early 1970s in a series of papers by John Corcoran and Timothy Smiley that inform modern translations of '' Prior Analytics'' by Robin Smith in 1989 and Gisela Striker in 2009. Łukasiewicz is regarded as one of the most important historians of logic. Life He was born in Lwów in Austria-Hungary (now Lviv, Ukr ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Many-valued Logic

Many-valued logic (also multi- or multiple-valued logic) is a propositional calculus in which there are more than two truth values. Traditionally, in Aristotle's Term logic, logical calculus, there were only two possible values (i.e., "true" and "false") for any proposition. Classical two-valued logic may be extended to ''n''-valued logic for ''n'' greater than 2. Those most popular in the literature are Three-valued logic, three-valued (e.g., Jan Łukasiewicz, Łukasiewicz's and Stephen Cole Kleene, Kleene's, which accept the values "true", "false", and "unknown"), four-valued logic, four-valued, nine-valued logic, nine-valued, the finite-valued logic, finite-valued (finitely-many valued) with more than three values, and the infinite-valued logic, infinite-valued (infinitely-many-valued), such as fuzzy logic and probabilistic logic, probability logic. History It is ''wrong'' that the first known classical logician who did not fully accept the law of excluded middle was Aristotle ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Individual

An individual is one that exists as a distinct entity. Individuality (or self-hood) is the state or quality of living as an individual; particularly (in the case of humans) as a person unique from other people and possessing one's own needs or goals, rights and responsibilities. The concept of an individual features in many fields, including biology, law, and philosophy. Every individual contributes significantly to the growth of a civilization. Society is a multifaceted concept that is shaped and influenced by a wide range of different things, including human behaviors, attitudes, and ideas. The culture, morals, and beliefs of others as well as the general direction and trajectory of the society can all be influenced and shaped by an individual's activities. Etymology From the 15th century and earlier (and also today within the fields of statistics and metaphysics) ''individual'' meant " indivisible", typically describing any numerically singular thing, but sometimes meani ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Concept

A concept is an abstract idea that serves as a foundation for more concrete principles, thoughts, and beliefs. Concepts play an important role in all aspects of cognition. As such, concepts are studied within such disciplines as linguistics, psychology, and philosophy, and these disciplines are interested in the logical and psychological structure of concepts, and how they are put together to form thoughts and sentences. The study of concepts has served as an important flagship of an emerging interdisciplinary approach, cognitive science. In contemporary philosophy, three understandings of a concept prevail: * mental representations, such that a concept is an entity that exists in the mind (a mental object) * abilities peculiar to cognitive agents (mental states) * Fregean senses, abstract objects rather than a mental object or a mental state Concepts are classified into a hierarchy, higher levels of which are termed "superordinate" and lower levels termed "subordinate". ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Monad (philosophy)

The term ''monad'' () is used in some cosmic philosophy and cosmogony to refer to a most basic or original substance. As originally conceived by the Pythagoreans, the Monad is therefore Supreme Being, divinity, or the totality of all things. According to some philosophers of the early modern period, most notably Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, there are infinite monads, which are the basic and immense forces, elementary particles, or simplest units, that make up the universe. Historical background According to Hippolytus, the worldview was inspired by the Pythagoreans, who called the first thing that came into existence the "monad", which begat (bore) the dyad (from the Greek word for two), which begat the numbers, which begat the point, begetting lines or finiteness, etc. It meant divinity, the first being, or the totality of all beings, referring in cosmogony (creation theories) variously to source acting alone and/or an indivisible origin and equivalent comparators. Py ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Substance Theory

Substance theory, or substance–attribute theory, is an ontological theory positing that objects are constituted each by a ''substance'' and properties borne by the substance but distinct from it. In this role, a substance can be referred to as a ''substratum'' or a '' thing-in-itself''. ''Substances'' are particulars that are ontologically independent: they are able to exist all by themselves. Another defining feature often attributed to substances is their ability to ''undergo changes''. Changes involve something existing ''before'', ''during'' and ''after'' the change. They can be described in terms of a persisting substance gaining or losing properties. ''Attributes'' or ''properties'', on the other hand, are entities that can be exemplified by substances. Properties characterize their bearers; they express what their bearer is like. ''Substance'' is a key concept in ontology, the latter in turn part of metaphysics, which may be classified into monist, dualist, or plural ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Subject (philosophy)

The distinction between subject and object is a basic idea of philosophy. *A subject is a being that exercises agency, undergoes conscious experiences, and is situated in relation to other things that exist outside itself; thus, a subject is any individual, person, or observer. *An object is any of the things observed or experienced by a subject, which may even include other beings (thus, from their own points of view: other subjects). A simple common differentiation for ''subject'' and ''object'' is: an observer versus a thing that is observed. In certain cases involving personhood, subjects and objects can be considered interchangeable where each label is applied only from one or the other point of view. Subjects and objects are related to the philosophical distinction between subjectivity and objectivity: the existence of knowledge, ideas, or information either dependent upon a subject (subjectivity) or independent from any subject (objectivity). Etymology In English the word ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Principle Of Sufficient Reason

The principle of sufficient reason states that everything must have a Reason (argument), reason or a cause. The principle was articulated and made prominent by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, with many antecedents, and was further used and developed by Arthur Schopenhauer and Sir William Hamilton, 9th Baronet, William Hamilton. History The modern formulation of the principle is usually ascribed to the early Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, Gottfried Leibniz, who formulated it, but was not its originator.See chapter on Leibniz and Spinoza in A. O. Lovejoy, ''The Great Chain of Being''. The idea was conceived of and utilized by various philosophers who preceded him, including Anaximander, Parmenides, Archimedes, Plato, Aristotle,Sir William Hamilton, 9th Baronet, Hamilton 1860:66. Cicero, Avicenna, Thomas Aquinas, and Baruch Spinoza. One often pointed to is in Anselm of Canterbury: his phrase ''quia Deus nihil sine ratione facit'' (because God d ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Compossible

Compossibility is a philosophical concept from Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. According to Leibniz, a complete individual thing (for example a person) is characterized by all its properties, and these determine its relations with other individuals. The existence of one individual may negate the possibility of the existence of another. A possible world is made up of individuals that are compossible—that is, individuals that can exist together. Compossibility and possible worlds Leibniz indicates that a world is a set of compossible things; ''i.e.,'' that a world is a kind of collection of things that God could bring into existence. For Leibniz, not even God could bring into existence a world in which there is some contradiction among its members or their properties. When Leibniz speaks of a possible world, he means a set of compossible, finite things that God could have brought into existence if he were not constrained by the goodness that is part of his nature. The actual world, ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

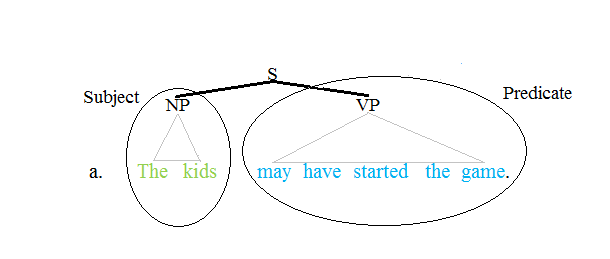

Predicate (grammar)

The term predicate is used in two ways in linguistics and its subfields. The first defines a predicate as everything in a standard declarative sentence except the subject (grammar), subject, and the other defines it as only the main content verb or associated predicative expression of a clause. Thus, by the first definition, the predicate of the sentence ''Frank likes cake'' is ''likes cake'', while by the second definition, it is only the content verb ''likes'', and ''Frank'' and ''cake'' are the argument (linguistics), arguments of this predicate. The conflict between these two definitions can lead to confusion. Syntax Traditional grammar The notion of a predicate in traditional grammar traces back to Aristotelian logic. A predicate is seen as a property that a subject has or is characterized by. A predicate is therefore an expression that can be ''true of'' something. Thus, the expression "is moving" is true of anything that is moving. This classical understanding of pred ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |