|

Geobacillus Stearothermophilus

''Geobacillus stearothermophilus'' (previously ''Bacillus stearothermophilus'') is a rod-shaped, Gram-positive bacterium and a member of the phylum Bacillota. The bacterium is a thermophile and is widely distributed in soil, hot springs, ocean sediment, and is a cause of spoilage in food products. It will grow within a temperature range of 30–75 °C. Some strains are capable of oxidizing carbon monoxide aerobically. It is commonly used as a challenge organism for sterilization validation studies and periodic check of sterilization cycles. The biological indicator contains spores of the organism on filter paper inside a vial. After sterilizing, the cap is closed, an ampule of growth medium inside of the vial is crushed and the whole vial is incubated. A color and/or turbidity change indicates the results of the sterilization process; no change indicates that the sterilization conditions were achieved, otherwise the growth of the spores indicates that the sterilizati ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

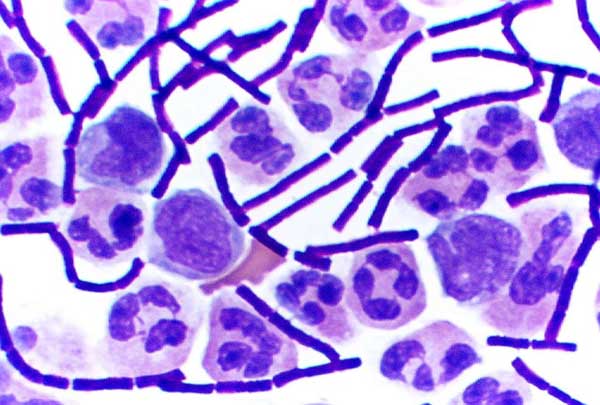

Gram-positive

In bacteriology, gram-positive bacteria are bacteria that give a positive result in the Gram stain test, which is traditionally used to quickly classify bacteria into two broad categories according to their type of cell wall. The Gram stain is used by microbiologists to place bacteria into two main categories, gram-positive (+) and gram-negative bacteria, gram-negative (−). Gram-positive bacteria have a thick layer of peptidoglycan within the cell wall, and gram-negative bacteria have a thin layer of peptidoglycan. Gram-positive bacteria retain the crystal violet stain used in the test, resulting in a purple color when observed through an optical microscope. The thick layer of peptidoglycan in the bacterial cell wall retains the Stain (biology), stain after it has been fixed in place by iodine. During the decolorization step, the decolorizer removes crystal violet from all other cells. Conversely, gram-negative bacteria cannot retain the violet stain after the decolorization ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Denaturation (biochemistry)

In biochemistry, denaturation is a process in which proteins or nucleic acids lose folded structure present in their native state due to various factors, including application of some external stress or compound, such as a strong acid or base, a concentrated inorganic salt, an organic solvent (e.g., alcohol or chloroform), agitation, radiation, or heat. If proteins in a living cell are denatured, this results in disruption of cell activity and possibly cell death. Protein denaturation is also a consequence of cell death. Denatured proteins can exhibit a wide range of characteristics, from conformational change and loss of solubility or dissociation of cofactors to aggregation due to the exposure of hydrophobic groups. The loss of solubility as a result of denaturation is called ''coagulation''. Denatured proteins, e.g., metalloenzymes, lose their 3D structure or metal cofactor, and therefore, cannot function. Proper protein folding is key to whether a globular or memb ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Dimethyl Sulfate

Dimethyl sulfate (DMS) is a chemical compound with formula (CH3O)2SO2. As the diester of methanol and sulfuric acid, its formula is often written as ( CH3)2 SO4 or Me2SO4, where CH3 or Me is methyl. Me2SO4 is mainly used as a methylating agent in organic synthesis. Me2SO4 is a colourless oily liquid with a slight onion-like odour. Like all strong alkylating agents, Me2SO4 is toxic. Its use as a laboratory reagent has been superseded to some extent by methyl triflate, CF3SO3CH3, the methyl ester of trifluoromethanesulfonic acid. History Impure dimethyl sulfate was prepared in the early 19th century. J. P. Claesson later extensively studied its preparation. It was investigated for possible use in chemical warfare in World War I in 75% to 25% mixture with methyl chlorosulfonate (CH3ClO3S) called "C-stoff" in Germany, or with chlorosulfonic acid called "Rationite" in France. The esterification of sulfuric acid with methanol was described in 1835: : Production Dimethyl s ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Methylation

Methylation, in the chemistry, chemical sciences, is the addition of a methyl group on a substrate (chemistry), substrate, or the substitution of an atom (or group) by a methyl group. Methylation is a form of alkylation, with a methyl group replacing a hydrogen#Compounds, hydrogen atom. These terms are commonly used in chemistry, biochemistry, soil science, and biology. In biological systems, methylation is Catalysis, catalyzed by enzymes; such methylation can be involved in modification of heavy metals, regulation of gene expression, regulation of Protein#Functions, protein function, and RNA processing. ''In vitro'' methylation of tissue samples is also a way to reduce some histology#Histological Artifacts, histological staining artifacts. The reverse of methylation is demethylation. In biology In biological systems, methylation is accomplished by enzymes. Methylation can modify heavy metals and can regulate gene expression, RNA processing, and protein function. It is a key pro ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Nucleic Acid Structure Determination

Experimental approaches of determining the Biomolecular structure, structure of nucleic acids, such as RNA and DNA, can be largely classified into biophysics, biophysical and biochemistry, biochemical methods. Biophysical methods use the fundamental physical properties of molecules for structure determination, including X-ray crystallography, Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, NMR and cryo-EM. Biochemical methods exploit the chemical properties of nucleic acids using specific reagents and conditions to assay the structure of nucleic acids. Such methods may involve chemical probing with specific reagents, or rely on native or nucleoside analogue, analogue chemistry. Different experimental approaches have unique merits and are suitable for different experimental purposes. Biophysical methods X-ray crystallography X-ray crystallography is not common for nucleic acids alone, since neither DNA nor RNA readily form crystals. This is due to the greater degree of intrinsic disor ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Processivity

In molecular biology and biochemistry, processivity is an enzyme's ability to catalyze "consecutive reactions without releasing its substrate". For example, processivity is the average number of nucleotides added by a polymerase enzyme, such as DNA polymerase, per association event with the template strand. Because the binding of the polymerase to the template is the rate-limiting step in DNA synthesis, the overall rate of DNA replication during S phase of the cell cycle is dependent on the processivity of the DNA polymerases performing the replication. DNA clamp proteins are integral components of the DNA replication machinery and serve to increase the processivity of their associated polymerases. Some polymerases add over 50,000 nucleotides to a growing DNA strand before dissociating from the template strand, giving a replication rate of up to 1,000 nucleotides per second. DNA binding interactions Polymerases interact with the phosphate backbone and the minor groove of the ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

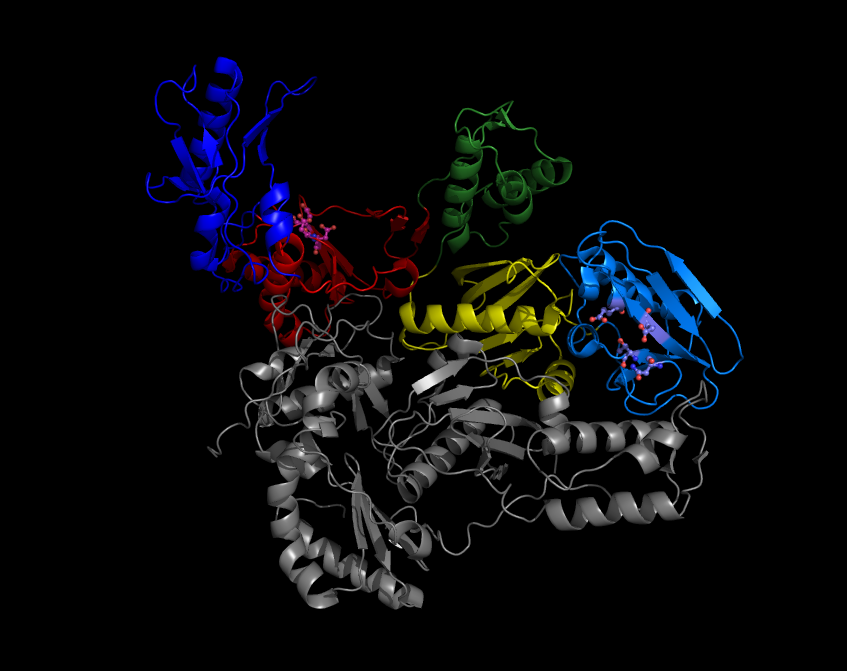

Reverse Transcriptase

A reverse transcriptase (RT) is an enzyme used to convert RNA genome to DNA, a process termed reverse transcription. Reverse transcriptases are used by viruses such as HIV and hepatitis B to replicate their genomes, by retrotransposon mobile genetic elements to proliferate within the host genome, and by eukaryotic cells to extend the telomeres at the ends of their linear chromosomes. The process does not violate the flows of genetic information as described by the classical central dogma, but rather expands it to include transfers of information from RNA to DNA. Retroviral RT has three sequential biochemical activities: RNA-dependent DNA polymerase activity, ribonuclease H (RNase H), and DNA-dependent DNA polymerase activity. Collectively, these activities enable the enzyme to convert single-stranded RNA into double-stranded cDNA. In retroviruses and retrotransposons, this cDNA can then integrate into the host genome, from which new RNA copies can be made via host-cell ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Group II Intron

Group II introns are a large class of self-catalytic ribozymes and mobile genetic elements found within the genes of all three domains of life. Ribozyme activity (e.g., self- splicing) can occur under high-salt conditions ''in vitro''. However, assistance from proteins is required for ''in vivo'' splicing. In contrast to group I introns, intron excision occurs in the absence of GTP and involves the formation of a lariat, with an A-residue branchpoint strongly resembling that found in lariats formed during splicing of nuclear pre-mRNA. It is hypothesized that pre-mRNA splicing (see spliceosome) may have evolved from group II introns, due to the similar catalytic mechanism as well as the structural similarity of the Group II Domain V substructure to the U6/U2 extended snRNA. Finally, their ability to site-specifically insert into DNA sites has been exploited as a tool for biotechnology. For example, group II introns can be modified to make site-specific genome insertions and d ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

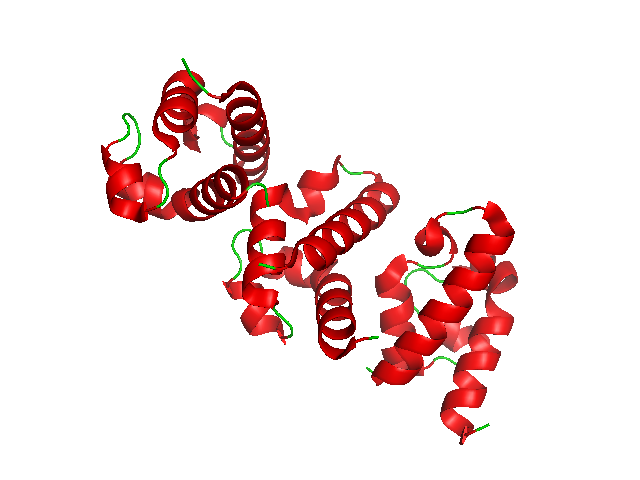

Thermostable

In materials science and molecular biology, thermostability is the ability of a substance to resist irreversible change in its chemical or physical structure, often by resisting decomposition or polymerization, at a high relative temperature. Thermostable materials may be used industrially as fire retardants. A ''thermostable plastic'', an uncommon and unconventional term, is likely to refer to a thermosetting plastic that cannot be reshaped when heated, than to a thermoplastic that can be remelted and recast. Thermostability is also a property of some proteins. To be a thermostable protein means to be resistant to changes in protein structure due to applied heat. Thermostable proteins Most life-forms on Earth live at temperatures of less than 50 °C, commonly from 15 to 50 °C. Within these organisms are macromolecules (proteins and nucleic acids) which form the three-dimensional structures essential to their enzymatic activity. Above the native temperature of the ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Polymerase Chain Reaction

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a method widely used to make millions to billions of copies of a specific DNA sample rapidly, allowing scientists to amplify a very small sample of DNA (or a part of it) sufficiently to enable detailed study. PCR was invented in 1983 by American biochemist Kary Mullis at Cetus Corporation. Mullis and biochemist Michael Smith (chemist), Michael Smith, who had developed other essential ways of manipulating DNA, were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1993. PCR is fundamental to many of the procedures used in genetic testing and research, including analysis of Ancient DNA, ancient samples of DNA and identification of infectious agents. Using PCR, copies of very small amounts of DNA sequences are exponentially amplified in a series of cycles of temperature changes. PCR is now a common and often indispensable technique used in medical laboratory research for a broad variety of applications including biomedical research and forensic ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Loop-mediated Isothermal Amplification

Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) is a single-tube technique for the amplification of DNA for diagnostic purposes and a low-cost alternative to detect certain diseases. LAMP is an isothermal nucleic acid amplification technique. In contrast to the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technology, in which the reaction is carried out with a series of alternating temperature steps or cycles, isothermal amplification is carried out at a constant temperature, and does not require a thermal cycler. LAMP was invented in 1998 by Eiken Chemical Company in Tokyo.M. Soroka, B. Wasowicz, A. Rymaszewska: ''Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP): The Better Sibling of PCR?'' In: ''Cells.'' Volume 10, issue 8, July 2021, p. , , PMID 34440699, . Reverse transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification (RT-LAMP) combines LAMP with a reverse transcription step to allow the detection of RNA. __TOC__ Amplification In LAMP, the target sequence is amplified at a constant ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Helicase

Helicases are a class of enzymes that are vital to all organisms. Their main function is to unpack an organism's genetic material. Helicases are motor proteins that move directionally along a nucleic double helix, separating the two hybridized nucleic acid strands (hence '' helic- + -ase''), via the energy gained from ATP hydrolysis. There are many helicases, representing the great variety of processes in which strand separation must be catalyzed. Approximately 1% of eukaryotic genes code for helicases. The human genome codes for 95 non-redundant helicases: 64 RNA helicases and 31 DNA helicases. Many cellular processes, such as DNA replication, transcription, translation, recombination, DNA repair and ribosome biogenesis involve the separation of nucleic acid strands that necessitates the use of helicases. Some specialized helicases are also involved in sensing viral nucleic acids during infection and fulfill an immunological function. Genetic mutations that affect helicase ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |