Young America movement on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Young America Movement was an American political, cultural and

The Young America Movement was an American political, cultural and

Apart from literature, there was a distinct element of art associated with the Young America Movement. In the 1820s and 1830s, American artists such as Asher B. Durand and

Apart from literature, there was a distinct element of art associated with the Young America Movement. In the 1820s and 1830s, American artists such as Asher B. Durand and

The Young America Movement and the Transformation of the Democratic Party 1828–1861

'. Cambridge University Press. * Lause, Mark A. (2005). ''Young America: Land, Labor, and the Republican Community''. Chicago: University of Illinois Press. * Widmer, Edward L. (1999).

Young America: The Flowering of Democracy in New York City

' New York: Oxford University Press .

HERE

"Trade and Improvements: Young America and the Transformation of the Democratic Party"

''Civil War History''. Vol. 51, Issue 3, pp. 245–68. . * Varon, Elizabeth R. (March 2009). "Review: Balancing Act: Young America's Struggle to Revive the Old Democracy". ''Reviews in American History''. Vol. 37, Issue 1, pp. 42–48. . {{Franklin Pierce Cultural history of the United States Democratic Party (United States) Factions in the Democratic Party (United States) Political history of the United States Jeffersonian democracy

The Young America Movement was an American political, cultural and

The Young America Movement was an American political, cultural and literary

Literature is any collection of written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially prose fiction, drama, and poetry. In recent centuries, the definition has expanded to includ ...

movement in the mid-19th century. Inspired by European reform movements of the 1830s (such as Junges Deutschland, Young Italy

Young Italy ( it, La Giovine Italia) was an Italian political movement founded in 1831 by Giuseppe Mazzini. After a few months of leaving Italy, in June 1831, Mazzini wrote a letter to King Charles Albert of Sardinia, in which he asked him to uni ...

and Young Hegelians

The Young Hegelians (german: Junghegelianer), or Left Hegelians (''Linkshegelianer''), or the Hegelian Left (''die Hegelsche Linke''), were a group of German intellectuals who, in the decade or so after the death of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel ...

), the American group was formed as a political organization in 1845 by Edwin de Leon and George Henry Evans

George Henry Evans (March 25, 1805February 2, 1856) was a radical reformer who was in the Working Men's movement of 1829 and the trade union movements of the 1830s. Evans was born in Bromyard, Herefordshire, England, the son of George Evans and S ...

. It advocated free trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. It can also be understood as the free market idea applied to international trade. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold econ ...

, social reform, expansion westward and southward into the territories, and support for republican, anti-aristocratic movements abroad. The movement also inspired a drive for self-consciously "American" literature in writers such as Nathaniel Hawthorne

Nathaniel Hawthorne (July 4, 1804 – May 19, 1864) was an American novelist and short story writer. His works often focus on history, morality, and religion.

He was born in 1804 in Salem, Massachusetts, from a family long associated with that t ...

, Herman Melville

Herman Melville ( born Melvill; August 1, 1819 – September 28, 1891) was an American novelist, short story writer, and poet of the American Renaissance period. Among his best-known works are '' Moby-Dick'' (1851); '' Typee'' (1846), a ...

, and Walt Whitman

Walter Whitman (; May 31, 1819 – March 26, 1892) was an American poet, essayist and journalist. A humanist, he was a part of the transition between transcendentalism and realism, incorporating both views in his works. Whitman is among ...

. It became a faction in the Democratic Party in the 1850s. Senator Stephen A. Douglas promoted its nationalistic program in an unsuccessful effort to compromise sectional differences. The breakup of the movement left many of its adherents discouraged and disillusioned.

John L. O'Sullivan described the general purpose of the Young America Movement in an 1837 editorial for the ''Democratic Review

''The United States Magazine and Democratic Review'' was a periodical published from 1837 to 1859 by John L. O'Sullivan. Its motto, "The best government is that which governs least", was famously paraphrased by Henry David Thoreau in "Resistance t ...

'':

Historian Edward L. Widmer places O'Sullivan and the ''Democratic Review'' in New York City at the center of the Young America Movement. In that sense, the movement can be considered mostly urban and middle class, but with a strong emphasis on socio-political reform for all Americans, especially given the burgeoning European immigrant population (particularly Irish Catholic

Irish Catholics are an ethnoreligious group native to Ireland whose members are both Catholic and Irish. They have a large diaspora, which includes over 36 million American citizens and over 14 million British citizens (a quarter of the Briti ...

s) in New York in the 1840s.

Politics

Historian Yonatan Eyal argues that the 1840s and 1850s were the heyday of the faction of young Democrats that called itself "Young America". Led byStephen Douglas

Stephen Arnold Douglas (April 23, 1813 – June 3, 1861) was an American politician and lawyer from Illinois. A senator, he was one of two nominees of the badly split Democratic Party for president in the 1860 presidential election, which wa ...

, James K. Polk and Franklin Pierce

Franklin Pierce (November 23, 1804October 8, 1869) was the 14th president of the United States, serving from 1853 to 1857. He was a northern Democrat who believed that the abolitionist movement was a fundamental threat to the nation's unity ...

, and New York financier August Belmont

August Belmont Sr. (born August Schönberg; December 8, 1813November 24, 1890) was a German-American financier, diplomat, politician and party chairman of the Democratic National Committee, and also a horse-breeder and racehorse owner. He wa ...

, this faction broke with the agrarian and strict constructionist orthodoxies of the past and embraced commerce, technology, regulation, reform, and internationalism.

In economic policy Young America saw the necessity of a modern infrastructure of railroads, canals, telegraphs, turnpikes, and harbors; they endorsed the "Market Revolution

The Market Revolution in 19th century United States is a historical model which argues that there was a drastic change of the economy that disoriented and coordinated all aspects of the market economy in line with both nations and the world. Char ...

" and promoted capitalism. They called for Congressional land grants to the states, which allowed Democrats to claim that internal improvements

Internal improvements is the term used historically in the United States for public works from the end of the American Revolution through much of the 19th century, mainly for the creation of a transportation infrastructure: roads, turnpikes, canal ...

were locally rather than federally sponsored. Young America claimed that modernization would perpetuate the agrarian vision of Jeffersonian Democracy

Jeffersonian democracy, named after its advocate Thomas Jefferson, was one of two dominant political outlooks and movements in the United States from the 1790s to the 1820s. The Jeffersonians were deeply committed to American republicanism, whic ...

by allowing yeomen farmers to sell their products and therefore to prosper. They tied internal improvements to free trade, while accepting moderate tariffs as a necessary source of government revenue. They supported the Independent Treasury (the Jacksonian alternative to the Second Bank of the United States), not as a scheme to quash the special privilege of the Whiggish moneyed elite, but as a device to spread prosperity to all Americans.

The movement's decline by 1856 was due to unsuccessful challenges to "old fogy" leaders like James Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was an American lawyer, diplomat and politician who served as the 15th president of the United States from 1857 to 1861. He previously served as secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and repr ...

, to Douglas' failure to win the presidential nomination in 1852, to an inability to deal with the slavery issue, and to rising isolationism and disenchantment with reform in America.

Manifest Destiny

When O'Sullivan coined the term "Manifest Destiny" in an 1845 article for the ''Democratic Review'', he did not necessarily intend for American democracy to expand across the continent by force. In effect, the American democratic principle was to spread on its own, self-evident merits. TheAmerican exceptionalism

American exceptionalism is the belief that the United States is inherently different from other nations.aristocracy

Aristocracy (, ) is a form of government that places strength in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocrats. The term derives from the el, αριστοκρατία (), meaning 'rule of the best'.

At the time of the word' ...

)". Unlike Europe, America had no aristocratic system or nobility against which Young America could define itself.

Literature

Aside from Young America's promotion ofJacksonian Democracy

Jacksonian democracy was a 19th-century political philosophy in the United States that expanded suffrage to most white men over the age of 21, and restructured a number of federal institutions. Originating with the seventh U.S. president, And ...

in the ''Democratic Review'', the movement also had a literary side. It attracted a circle of outstanding writers, including William Cullen Bryant

William Cullen Bryant (November 3, 1794 – June 12, 1878) was an American romantic poet, journalist, and long-time editor of the ''New York Evening Post''. Born in Massachusetts, he started his career as a lawyer but showed an interest in poetry ...

, George Bancroft

George Bancroft (October 3, 1800 – January 17, 1891) was an American historian, statesman and Democratic politician who was prominent in promoting secondary education both in his home state of Massachusetts and at the national and internati ...

, Herman Melville

Herman Melville ( born Melvill; August 1, 1819 – September 28, 1891) was an American novelist, short story writer, and poet of the American Renaissance period. Among his best-known works are '' Moby-Dick'' (1851); '' Typee'' (1846), a ...

, and Nathaniel Hawthorne

Nathaniel Hawthorne (July 4, 1804 – May 19, 1864) was an American novelist and short story writer. His works often focus on history, morality, and religion.

He was born in 1804 in Salem, Massachusetts, from a family long associated with that t ...

. They sought independence from European standards of high culture and wanted to demonstrate the excellence and "exceptionalism" of America's own literary tradition. Other writers of the movement included Evert Augustus Duyckinck

Evert Augustus Duyckinck (pronounced DIE-KINK) (November 23, 1816 – August 13, 1878) was an American publisher and biographer. He was associated with the literary side of the Young America movement in New York.

Biography

He was born on Novem ...

, Cornelius Mathews

Cornelius Mathews (October 28, 1817 – March 25, 1889) was an American writer, best known for his crucial role in the formation of a literary group known as Young America in the late 1830s, with editor Evert Duyckinck and author William Gi ...

, It was Mathews that adopted the name for the movement. In a speech delivered June 30, 1845, he said:

One of Young America's intellectual vehicles was the literary journal ''Arcturus''. Herman Melville

Herman Melville ( born Melvill; August 1, 1819 – September 28, 1891) was an American novelist, short story writer, and poet of the American Renaissance period. Among his best-known works are '' Moby-Dick'' (1851); '' Typee'' (1846), a ...

in his book ''Mardi

''Mardi: and a Voyage Thither'' is the third book by American writer Herman Melville, first published in London in 1849. Beginning as a travelogue in the vein of the author's two previous efforts, the adventure story gives way to a romance story, ...

'' (1849) refers to it by naming a ship in the book ''Arcturion'' and observing that it was "exceedingly dull", and that its crew had a low literary level. The ''North American Review

The ''North American Review'' (NAR) was the first literary magazine in the United States. It was founded in Boston in 1815 by journalist Nathan Hale and others. It was published continuously until 1940, after which it was inactive until revived at ...

'' referred to the movement as "at war with good taste".

Hudson River School

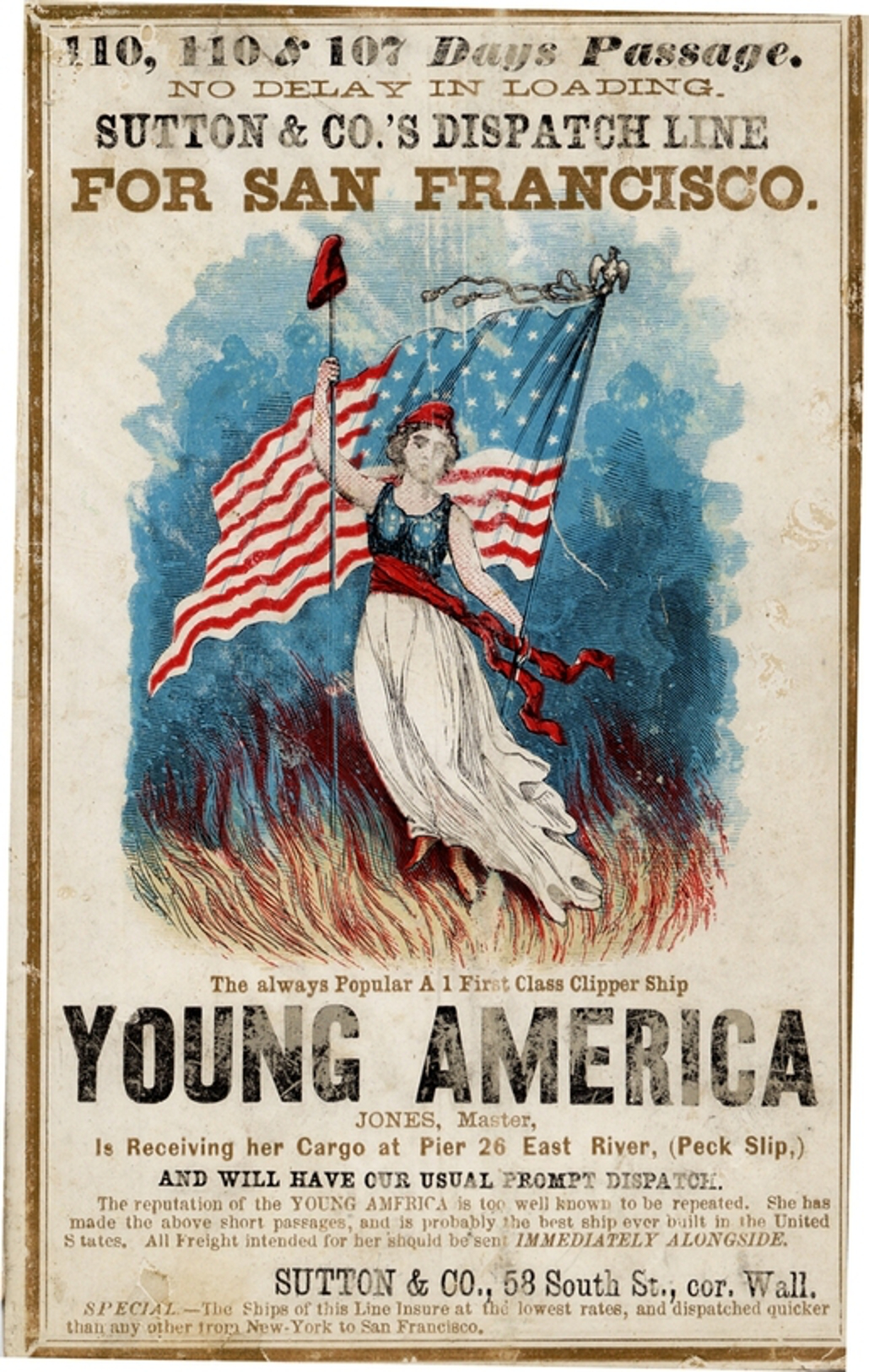

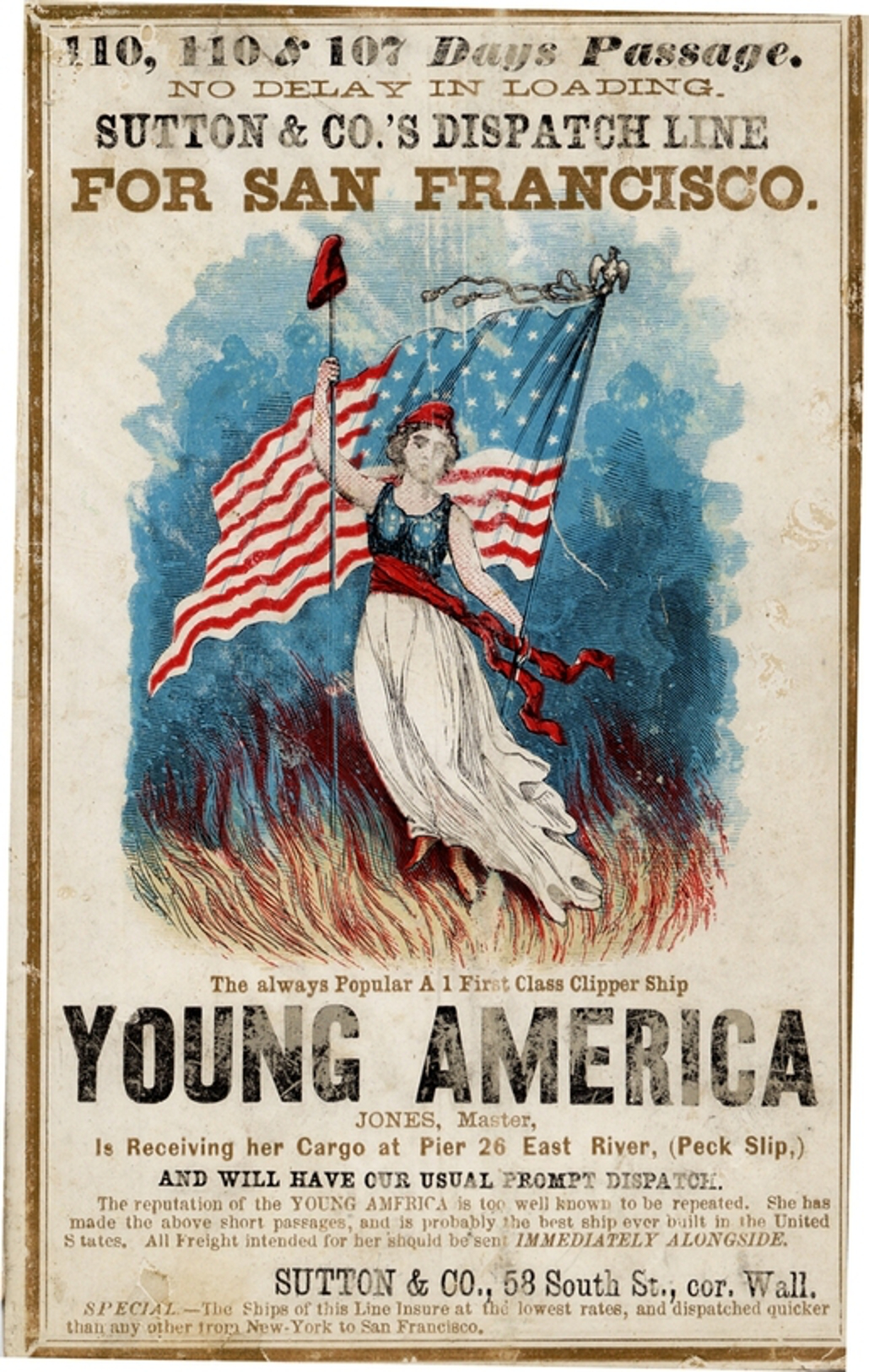

Apart from literature, there was a distinct element of art associated with the Young America Movement. In the 1820s and 1830s, American artists such as Asher B. Durand and

Apart from literature, there was a distinct element of art associated with the Young America Movement. In the 1820s and 1830s, American artists such as Asher B. Durand and Thomas Cole

Thomas Cole was an English-born American artist and the founder of the Hudson River School art movement. Cole is widely regarded as the first significant American landscape painter. He was known for his romantic landscape and history painti ...

began to emerge. They were heavily influenced by romanticism

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic, literary, musical, and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century, and in most areas was at its peak in the approximate ...

, which resulted in numerous paintings involving the physical landscape

A landscape is the visible features of an area of land, its landforms, and how they integrate with natural or man-made features, often considered in terms of their aesthetic appeal.''New Oxford American Dictionary''. A landscape includes the ...

. But it was William Sidney Mount

William Sidney Mount (November 26, 1807 – November 19, 1868) was a 19th-century American genre painter. Born in Setauket in 1807, Mount spent much of his life in his hometown and the adjacent village of Stony Brook, where he painted portraits, ...

who had connections to the writers of the ''Democratic Review''. And as a contemporary of the Hudson River School, he sought to use art in the promotion of the American democratic principle. O'Sullivan's cohort at the ''Review'', E. A. Duyckinck, was particularly "eager to launch an ancillary artistic movement" that supplemented Young America.

Young America II

In late 1851, the ''Democratic Review'' was acquired by George Nicholas Sanders. Similar to O'Sullivan, Sanders believed in the inherent value of a literary-political relationship, whereby literature and politics could be combined and used as an instrument for socio-political progress. Although he "brought O'Sullivan back into the fold as an editor", the periodical's "jingoism

Jingoism is nationalism in the form of aggressive and proactive foreign policy, such as a country's advocacy for the use of threats or actual force, as opposed to peaceful relations, in efforts to safeguard what it perceives as its national int ...

achieved an even higher pitch than O'Sullivan's riginaldog-whistle stridency". Even Democratic Representative John C. Breckinridge remarked in 1852:

The change in tone and partisanship in the ''Democratic Review'' that Breckinridge referred to was mostly a reaction by the increasingly divided Democratic Party to the growth of the Free Soil movement, which threatened to dissolve any semblance of Democratic unity that remained.

Rise of Labor Republicanism

By the mid-1850s, Free Soil Democrats (those who followedDavid Wilmot

David Wilmot (January 20, 1814 – March 16, 1868) was an American politician and judge. He served as Representative and a Senator for Pennsylvania and as a judge of the Court of Claims. He is best known for being the prime sponsor and ep ...

and his Proviso

Proviso means ''a conditional provision to an agreement''. It may refer to

*Proviso Township, Cook County, Illinois, United States

**Proviso Township High Schools District 209 that comprises

***Proviso East High School

***Proviso West High School

* ...

) and anti-slavery Whigs had combined to form the Republican Party

Republican Party is a name used by many political parties around the world, though the term most commonly refers to the United States' Republican Party.

Republican Party may also refer to:

Africa

* Republican Party (Liberia)

*Republican Party ...

. Young America's New York Democrats who opposed slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

saw an opportunity to express their abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

sentiments. As a result, Horace Greeley

Horace Greeley (February 3, 1811 – November 29, 1872) was an American newspaper editor and publisher who was the founder and editor of the '' New-York Tribune''. Long active in politics, he served briefly as a congressman from New York ...

's ''New York Tribune

The ''New-York Tribune'' was an American newspaper founded in 1841 by editor Horace Greeley. It bore the moniker ''New-York Daily Tribune'' from 1842 to 1866 before returning to its original name. From the 1840s through the 1860s it was the domi ...

'' began to replace the ''Democratic Review'' as the central outlet for Young America's ever-evolving politics. In fact, Greeley's ''Tribune'' became a major advocate of not only abolition, but also of land and labor reform.

The combined cause of land and labor reform was perhaps best exemplified by George Henry Evans

George Henry Evans (March 25, 1805February 2, 1856) was a radical reformer who was in the Working Men's movement of 1829 and the trade union movements of the 1830s. Evans was born in Bromyard, Herefordshire, England, the son of George Evans and S ...

' National Reform Association (NRA). In 1846, Evans stated:

Eventually, former members of the radical Locofoco faction in the Democratic Party recognized the potential for reorganizing New York City's labor system around principles such as the common good

In philosophy, economics, and political science, the common good (also commonwealth, general welfare, or public benefit) is either what is shared and beneficial for all or most members of a given community, or alternatively, what is achieved by c ...

. In contrast to the Europe in the days of the 1848 revolutions, America had no aristocratic establishment against which Young America could define itself in protest.

See also

*David Dudley Field II

David Dudley Field II (February 13, 1805April 13, 1894) was an American lawyer and law reformer who made major contributions to the development of American civil procedure. His greatest accomplishment was engineering the move away from common ...

* Popular sovereignty in the United States

Popular sovereignty is a doctrine rooted in the belief that each citizen has sovereignty over themselves. Citizens may unite and offer to delegate a portion of their sovereign powers and duties to those who wish to serve as officers of the state, ...

* Henry David Thoreau

Henry David Thoreau (July 12, 1817May 6, 1862) was an American naturalist, essayist, poet, and philosopher. A leading transcendentalist, he is best known for his book ''Walden'', a reflection upon simple living in natural surroundings, and h ...

* Walt Whitman

Walter Whitman (; May 31, 1819 – March 26, 1892) was an American poet, essayist and journalist. A humanist, he was a part of the transition between transcendentalism and realism, incorporating both views in his works. Whitman is among ...

Citations

General references

* Danbom, David B. (September 1974). "The Young America Movement", ''Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society''. Vol. 67, Issue 3, pp. 294–306. * Eyal, Yonatan. (2007).The Young America Movement and the Transformation of the Democratic Party 1828–1861

'. Cambridge University Press. * Lause, Mark A. (2005). ''Young America: Land, Labor, and the Republican Community''. Chicago: University of Illinois Press. * Widmer, Edward L. (1999).

Young America: The Flowering of Democracy in New York City

' New York: Oxford University Press .

Internet Archive

The Internet Archive is an American digital library with the stated mission of "universal access to all knowledge". It provides free public access to collections of digitized materials, including websites, software applications/games, music, ...

: Free onlinHERE

Further reading

* Eyal, Yonatan (September 2005)"Trade and Improvements: Young America and the Transformation of the Democratic Party"

''Civil War History''. Vol. 51, Issue 3, pp. 245–68. . * Varon, Elizabeth R. (March 2009). "Review: Balancing Act: Young America's Struggle to Revive the Old Democracy". ''Reviews in American History''. Vol. 37, Issue 1, pp. 42–48. . {{Franklin Pierce Cultural history of the United States Democratic Party (United States) Factions in the Democratic Party (United States) Political history of the United States Jeffersonian democracy