Yorktown campaign on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Yorktown campaign, also known as the Virginia campaign, was a series of military maneuvers and battles during the

As the French fleet was preparing to depart Brest in March, several important decisions were made. The West Indies fleet, led by the

As the French fleet was preparing to depart Brest in March, several important decisions were made. The West Indies fleet, led by the

General Clinton never articulated a coherent vision for what the goals for British operations of the coming campaign season should be in the early months of 1781. Part of his problem lay in a difficult relationship with his naval counterpart in New York, the aging Vice Admiral

General Clinton never articulated a coherent vision for what the goals for British operations of the coming campaign season should be in the early months of 1781. Part of his problem lay in a difficult relationship with his naval counterpart in New York, the aging Vice Admiral

Part of the fleet carrying General Arnold and his troops arrived in

Part of the fleet carrying General Arnold and his troops arrived in  Congress authorised a detachment of Continental forces to Virginia on February 20. Washington assigned command of the expedition to the

Congress authorised a detachment of Continental forces to Virginia on February 20. Washington assigned command of the expedition to the

The departure of Destouches' fleet from Newport had prompted General Clinton to send Arnold reinforcements. In the wake of Arbuthnot's sailing he sent transports carrying about 2,000 men under the command of General

The departure of Destouches' fleet from Newport had prompted General Clinton to send Arnold reinforcements. In the wake of Arbuthnot's sailing he sent transports carrying about 2,000 men under the command of General

To counter the British threat in the Carolinas, Washington had sent Major General

To counter the British threat in the Carolinas, Washington had sent Major General  Cornwallis, after dispatching General Arnold back to New York, then set out to follow General Clinton's most recent orders to Phillips.Russell, p. 256Carrington, p. 595 These instructions were to establish a fortified base and raid rebel military and economic targets in Virginia. Cornwallis decided that he had to first deal with the threat posed by Lafayette, so he set out in pursuit of the marquis. Lafayette, clearly outnumbered, retreated rapidly toward Fredericksburg to protect an important supply depot there,Clary, p. 306 while von Steuben retreated to Point of Fork (present-day

Cornwallis, after dispatching General Arnold back to New York, then set out to follow General Clinton's most recent orders to Phillips.Russell, p. 256Carrington, p. 595 These instructions were to establish a fortified base and raid rebel military and economic targets in Virginia. Cornwallis decided that he had to first deal with the threat posed by Lafayette, so he set out in pursuit of the marquis. Lafayette, clearly outnumbered, retreated rapidly toward Fredericksburg to protect an important supply depot there,Clary, p. 306 while von Steuben retreated to Point of Fork (present-day  After the successful raids of Simcoe and Tarleton, Cornwallis began to make his way east toward Richmond and Williamsburg, almost contemptuously ignoring Lafayette in his movements. Lafayette, his force grown to about 4,500, was buoyed in confidence, and began to edge closer to the earl's army. By the time Cornwallis reached Williamsburg on June 25, Lafayette was away, at Bird's Tavern. That day, Lafayette learned that Simcoe's Queen's Rangers were at some remove from the main British force, so Lafayette sent some cavalry and light infantry to intercept them. This precipitated a skirmish at Spencer's Ordinary where each side believed the other to be within range of its main army.

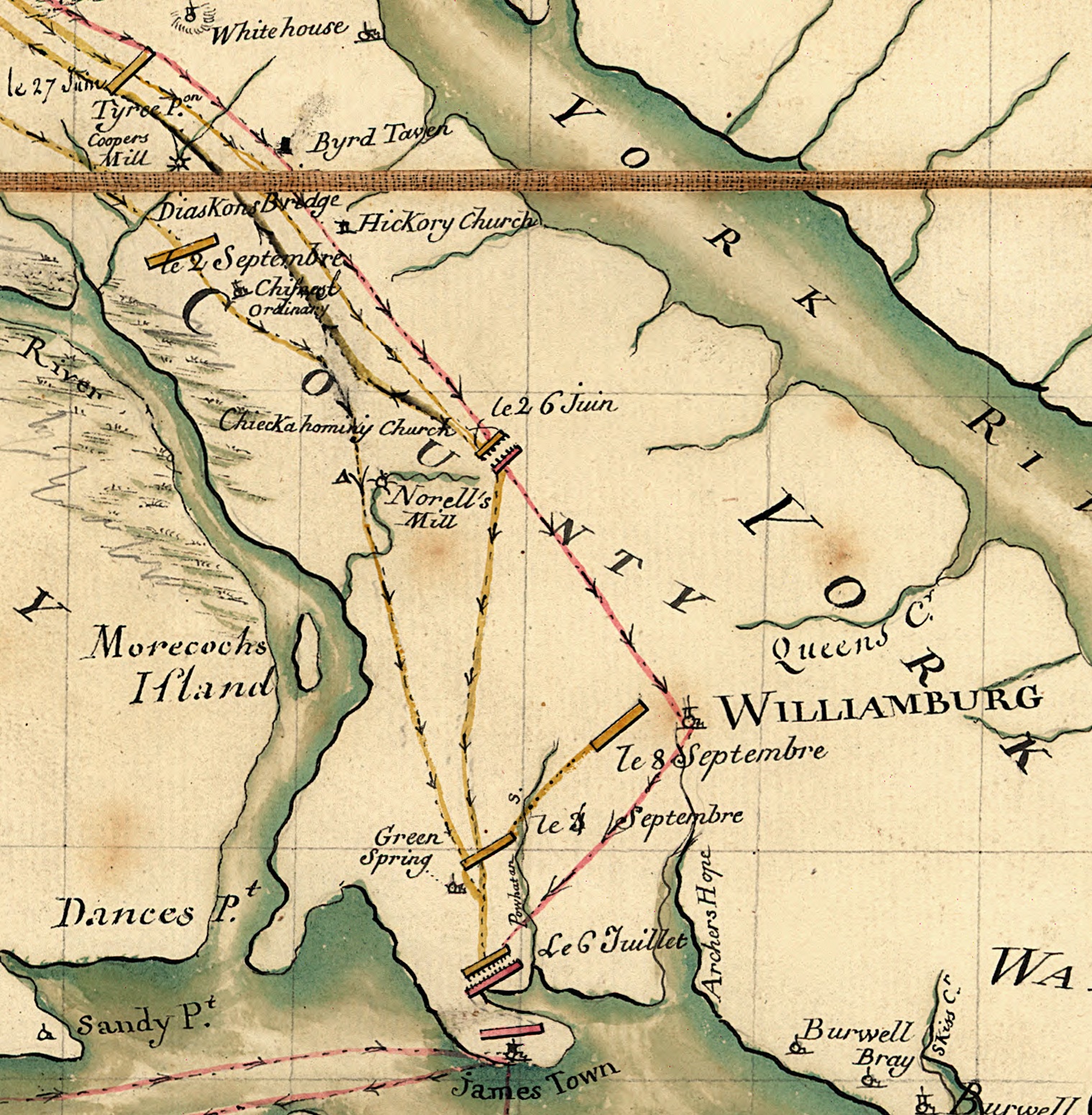

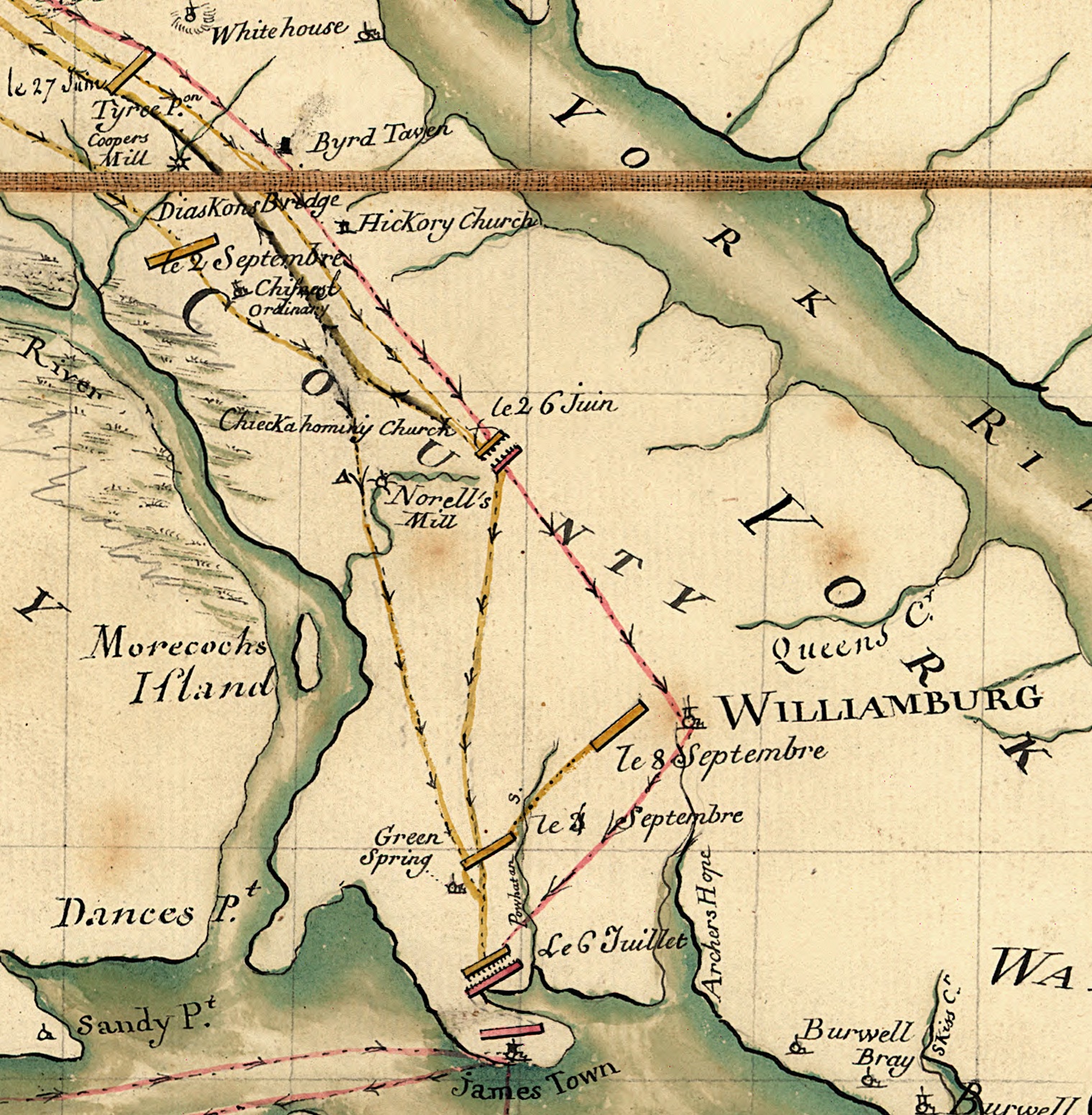

After the successful raids of Simcoe and Tarleton, Cornwallis began to make his way east toward Richmond and Williamsburg, almost contemptuously ignoring Lafayette in his movements. Lafayette, his force grown to about 4,500, was buoyed in confidence, and began to edge closer to the earl's army. By the time Cornwallis reached Williamsburg on June 25, Lafayette was away, at Bird's Tavern. That day, Lafayette learned that Simcoe's Queen's Rangers were at some remove from the main British force, so Lafayette sent some cavalry and light infantry to intercept them. This precipitated a skirmish at Spencer's Ordinary where each side believed the other to be within range of its main army.

While Lafayette, Arnold, and Phillips manoeuvred in Virginia, the allied leaders, Washington and Rochambeau, considered their options. On May 6 the ''Concorde'' arrived in Boston, and two days later Washington and Rochambeau were informed of the arrival of de Barras as well as the vital dispatches and funding. On May 23 and 24, Washington and Rochambeau held a conference at

While Lafayette, Arnold, and Phillips manoeuvred in Virginia, the allied leaders, Washington and Rochambeau, considered their options. On May 6 the ''Concorde'' arrived in Boston, and two days later Washington and Rochambeau were informed of the arrival of de Barras as well as the vital dispatches and funding. On May 23 and 24, Washington and Rochambeau held a conference at

On July 4 Cornwallis began moving his army toward the Jamestown ferry, to cross the broad

On July 4 Cornwallis began moving his army toward the Jamestown ferry, to cross the broad  When Cornwallis reached Portsmouth, he began embarking troops pursuant to Clinton's orders. On July 20, with some transports almost ready to sail, new orders arrived that countermanded the previous ones. In the most direct terms, Clinton ordered him to establish a fortified deep-water port, using as much of his army as he thought necessary. Clinton took this decision because the navy had long been dissatisfied with New York as a naval base, firstly because sand bars obstructed the entrance to the Hudson River, damaging the hulls of the larger ships; and secondly because the river often froze in winter, imprisoning vessels inside the harbour. Arbuthnot had recently been replaced and to show his satisfaction at this development, Clinton now acceded to the Navy's request, despite Cornwallis's warning that the Chesapeake's open bays and navigable rivers meant that any base there "will always be exposed to sudden French attack." It was to prove a fatal error of judgement by Clinton, since the need to defend the new facility denied Cornwallis any freedom of movement. Nevertheless, having inspected Portsmouth and found it less favourable than Yorktown, Cornwallis wrote to Clinton informing him that he would fortify Yorktown.

Lafayette was alerted on July 26 that Cornwallis was embarking his troops, but lacked intelligence about their eventual destination, and began manoeuvring his troops to cover some possible landing points. On August 6 he learned that Cornwallis had landed at Yorktown and was fortifying it and

When Cornwallis reached Portsmouth, he began embarking troops pursuant to Clinton's orders. On July 20, with some transports almost ready to sail, new orders arrived that countermanded the previous ones. In the most direct terms, Clinton ordered him to establish a fortified deep-water port, using as much of his army as he thought necessary. Clinton took this decision because the navy had long been dissatisfied with New York as a naval base, firstly because sand bars obstructed the entrance to the Hudson River, damaging the hulls of the larger ships; and secondly because the river often froze in winter, imprisoning vessels inside the harbour. Arbuthnot had recently been replaced and to show his satisfaction at this development, Clinton now acceded to the Navy's request, despite Cornwallis's warning that the Chesapeake's open bays and navigable rivers meant that any base there "will always be exposed to sudden French attack." It was to prove a fatal error of judgement by Clinton, since the need to defend the new facility denied Cornwallis any freedom of movement. Nevertheless, having inspected Portsmouth and found it less favourable than Yorktown, Cornwallis wrote to Clinton informing him that he would fortify Yorktown.

Lafayette was alerted on July 26 that Cornwallis was embarking his troops, but lacked intelligence about their eventual destination, and began manoeuvring his troops to cover some possible landing points. On August 6 he learned that Cornwallis had landed at Yorktown and was fortifying it and

On August 14 General Washington learned of de Grasse's decision to sail for the Chesapeake. The next day he reluctantly abandoned the idea of assaulting New York, writing that " tters having now come to a crisis and a decisive plan to be determined on, I was obliged ... to give up all idea of attacking New York..."Ketchum, p. 151 The combined Franco-American army began moving south on August 19, engaging in several tactics designed to fool Clinton about their intentions. Some forces were sent on a route along the New Jersey shore, and ordered to make camp preparations as if preparing for an attack on Staten Island. The army also carried landing craft to lend verisimilitude to the idea. Washington sent orders to Lafayette to prevent Cornwallis from returning to North Carolina; he did not learn that Cornwallis was entrenching at Yorktown until August 30. Two days later the army was passing through Philadelphia; another mutiny was averted there when funds were procured for troops that threatened to stay until they were paid.

On August 14 General Washington learned of de Grasse's decision to sail for the Chesapeake. The next day he reluctantly abandoned the idea of assaulting New York, writing that " tters having now come to a crisis and a decisive plan to be determined on, I was obliged ... to give up all idea of attacking New York..."Ketchum, p. 151 The combined Franco-American army began moving south on August 19, engaging in several tactics designed to fool Clinton about their intentions. Some forces were sent on a route along the New Jersey shore, and ordered to make camp preparations as if preparing for an attack on Staten Island. The army also carried landing craft to lend verisimilitude to the idea. Washington sent orders to Lafayette to prevent Cornwallis from returning to North Carolina; he did not learn that Cornwallis was entrenching at Yorktown until August 30. Two days later the army was passing through Philadelphia; another mutiny was averted there when funds were procured for troops that threatened to stay until they were paid.

Admiral de Barras sailed with his fleet from Newport, carrying the French siege equipment, on August 25. He sailed a route that deliberately took him away from the coast to avoid encounters with the British. De Grasse reached the Chesapeake on August 30, five days after Hood. He immediately debarked the troops from his fleet to assist Lafayette in blockading Cornwallis, and stationed some his ships to blockade the York and James Rivers.

News of de Barras' sailing reached New York on August 28, where Graves, Clinton, and Hood were meeting to discuss the possibility of making an attack on the French fleet in Newport, since the French army was no longer there to defend it. Clinton had still not realized that Washington was marching south, something he did not have confirmed until September 2. When they learned of de Barras' departure they immediately concluded that de Grasse must be headed for the Chesapeake (but still did not know of his strength). Graves sailed from New York on August 31 with 19 ships of the line; Clinton wrote Cornwallis to warn him that Washington was coming, and that he would send 4,000 reinforcements.

Admiral de Barras sailed with his fleet from Newport, carrying the French siege equipment, on August 25. He sailed a route that deliberately took him away from the coast to avoid encounters with the British. De Grasse reached the Chesapeake on August 30, five days after Hood. He immediately debarked the troops from his fleet to assist Lafayette in blockading Cornwallis, and stationed some his ships to blockade the York and James Rivers.

News of de Barras' sailing reached New York on August 28, where Graves, Clinton, and Hood were meeting to discuss the possibility of making an attack on the French fleet in Newport, since the French army was no longer there to defend it. Clinton had still not realized that Washington was marching south, something he did not have confirmed until September 2. When they learned of de Barras' departure they immediately concluded that de Grasse must be headed for the Chesapeake (but still did not know of his strength). Graves sailed from New York on August 31 with 19 ships of the line; Clinton wrote Cornwallis to warn him that Washington was coming, and that he would send 4,000 reinforcements.

On September 5, the British fleet arrived at the mouth of the Chesapeake to see the French fleet anchored there. De Grasse, who had men ashore, was forced to cut his cables and scramble to get his fleet out to meet the British. In the Battle of the Chesapeake, de Grasse won a narrow tactical victory. After the battle, the two fleets drifted to the southeast for several days, with the British avoiding battle and both fleets making repairs. This was apparently in part a ploy by de Grasse to ensure the British would not interfere with de Barras' arrival. A fleet was spotted off in the distance on September 9 making for the bay; de Grasse followed the next day. Graves, forced to scuttle one of his ships, returned to New York for repairs. Smaller ships from the French fleet then assisted in transporting the Franco-American army down the Chesapeake to Yorktown, completing the encirclement of Cornwallis.

On September 5, the British fleet arrived at the mouth of the Chesapeake to see the French fleet anchored there. De Grasse, who had men ashore, was forced to cut his cables and scramble to get his fleet out to meet the British. In the Battle of the Chesapeake, de Grasse won a narrow tactical victory. After the battle, the two fleets drifted to the southeast for several days, with the British avoiding battle and both fleets making repairs. This was apparently in part a ploy by de Grasse to ensure the British would not interfere with de Barras' arrival. A fleet was spotted off in the distance on September 9 making for the bay; de Grasse followed the next day. Graves, forced to scuttle one of his ships, returned to New York for repairs. Smaller ships from the French fleet then assisted in transporting the Franco-American army down the Chesapeake to Yorktown, completing the encirclement of Cornwallis.

On September 6, General Clinton wrote a letter to Cornwallis, telling him to expect reinforcements. Received by Cornwallis on September 14, this letter may have been instrumental in the decision by Cornwallis to remain at Yorktown and not try to fight his way out, despite the urging of Banastre Tarleton to break out against the comparatively weak Lafayette. General Washington, after spending a few days at

On September 6, General Clinton wrote a letter to Cornwallis, telling him to expect reinforcements. Received by Cornwallis on September 14, this letter may have been instrumental in the decision by Cornwallis to remain at Yorktown and not try to fight his way out, despite the urging of Banastre Tarleton to break out against the comparatively weak Lafayette. General Washington, after spending a few days at  Washington, Rochambeau, and de Grasse then held council aboard de Grasse's flagship ''Ville de Paris'' to finalize preparations for the siege; de Grasse agreed to provide about 2,000 marines and some cannons to the effort. During the meeting, de Grasse was convinced to delay his departure (originally planned for mid-October) until the end of October. Upon the return of the generals to Williamsburg, they heard rumors that British naval reinforcements had arrived at New York, and the French fleet might again be threatened. De Grasse wanted to pull his fleet out of the bay as a precaution, and it took the pleas of Washington and Rochambeau, delivered to de Grasse by Lafayette, to convince him to remain.

The siege formally got underway on September 28. Despite a late attempt by Cornwallis to escape via Gloucester Point, the siege lines closed in on his positions and the allied cannons wrought havoc in the British camps, and on October 17 he opened negotiations to surrender. On that very day, the British fleet again sailed from New York, carrying 6,000 troops. Still outnumbered by the combined French fleets, they eventually turned back. A French naval officer, noting the British fleet's departure on October 29, wrote, "They were too late. The fowl had been eaten."

Washington, Rochambeau, and de Grasse then held council aboard de Grasse's flagship ''Ville de Paris'' to finalize preparations for the siege; de Grasse agreed to provide about 2,000 marines and some cannons to the effort. During the meeting, de Grasse was convinced to delay his departure (originally planned for mid-October) until the end of October. Upon the return of the generals to Williamsburg, they heard rumors that British naval reinforcements had arrived at New York, and the French fleet might again be threatened. De Grasse wanted to pull his fleet out of the bay as a precaution, and it took the pleas of Washington and Rochambeau, delivered to de Grasse by Lafayette, to convince him to remain.

The siege formally got underway on September 28. Despite a late attempt by Cornwallis to escape via Gloucester Point, the siege lines closed in on his positions and the allied cannons wrought havoc in the British camps, and on October 17 he opened negotiations to surrender. On that very day, the British fleet again sailed from New York, carrying 6,000 troops. Still outnumbered by the combined French fleets, they eventually turned back. A French naval officer, noting the British fleet's departure on October 29, wrote, "They were too late. The fowl had been eaten."

Over the following weeks, the army was marched under guard to camps in Virginia and Maryland. Cornwallis and other officers were returned to New York and allowed to return to England on parole. The ship on which Cornwallis sailed in December 1781 also carried Benedict Arnold and his family.Randall, p. 585

Over the following weeks, the army was marched under guard to camps in Virginia and Maryland. Cornwallis and other officers were returned to New York and allowed to return to England on parole. The ship on which Cornwallis sailed in December 1781 also carried Benedict Arnold and his family.Randall, p. 585

Historian John Pancake describes the later stages of the campaign as "British blundering" and that the "allied operations proceeded with clockwork precision." Naval historian Jonathan Dull has described de Grasse's 1781 naval campaign, which encompassed, in addition to Yorktown, successful contributions to the French capture of Tobago and the Spanish siege of Pensacola, as the "most perfectly executed naval campaign of the age of sail", and compared the string of French successes favorably with the British Annus Mirabilis of 1759.Dull, p. 247 He also observes that a significant number of individual decisions, at times against orders or previous agreements, contributed to the success of the campaign:Dull, pp. 247-248

#French ministers Montmorin and Vergennes convinced the French establishment that decisive action was needed in North America in order to end the war.

#The French naval minister Castries wrote orders for de Grasse that gave the latter sufficient flexibility to assist in the campaign.

#Spanish Louisiana Governor

Historian John Pancake describes the later stages of the campaign as "British blundering" and that the "allied operations proceeded with clockwork precision." Naval historian Jonathan Dull has described de Grasse's 1781 naval campaign, which encompassed, in addition to Yorktown, successful contributions to the French capture of Tobago and the Spanish siege of Pensacola, as the "most perfectly executed naval campaign of the age of sail", and compared the string of French successes favorably with the British Annus Mirabilis of 1759.Dull, p. 247 He also observes that a significant number of individual decisions, at times against orders or previous agreements, contributed to the success of the campaign:Dull, pp. 247-248

#French ministers Montmorin and Vergennes convinced the French establishment that decisive action was needed in North America in order to end the war.

#The French naval minister Castries wrote orders for de Grasse that gave the latter sufficient flexibility to assist in the campaign.

#Spanish Louisiana Governor

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

that culminated in the siege of Yorktown

The Siege of Yorktown, also known as the Battle of Yorktown, the surrender at Yorktown, or the German battle (from the presence of Germans in all three armies), beginning on September 28, 1781, and ending on October 19, 1781, at Yorktown, Virg ...

in October 1781. The result of the campaign was the surrender of the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurkha ...

force of General Charles Earl Cornwallis, an event that led directly to the beginning of serious peace negotiations and the eventual end of the war. The campaign was marked by disagreements, indecision, and miscommunication on the part of British leaders, and by a remarkable set of cooperative decisions, at times in violation of orders, by the French and Americans.

The campaign involved land and naval forces of Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It ...

and France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, and land forces of the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

. British forces were sent to Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth are ...

between January and April 1781 and joined with Cornwallis's army in May, which came north from an extended campaign through the southern states. These forces were first opposed weakly by Virginia militia, but General George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

sent first Marquis de Lafayette

Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de La Fayette (6 September 1757 – 20 May 1834), known in the United States as Lafayette (, ), was a French aristocrat, freemason and military officer who fought in the American Revolutio ...

and then "Mad" Anthony Wayne with Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies (the Thirteen Colonies) in the Revolutionary-era United States. It was formed by the Second Continental Congress after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, and was establis ...

troops to oppose the raiding and economic havoc the British were wreaking. The combined American forces, however, were insufficient in number to oppose the combined British forces, and it was only after a series of controversially confusing orders by General Sir Henry Clinton, the British commander-in-chief, that Cornwallis moved to Yorktown in July and built a defensive position that was strong against the land forces he then faced, but was vulnerable to naval blockade and siege.

British naval forces in North America and the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greate ...

were weaker than the combined fleets of France and Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

, and, after some critical decisions and tactical missteps by British naval commanders, the French fleet of Paul de Grasse gained control over Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The Bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula (including the parts: the Eastern Shore of Maryland / ...

, blockading Cornwallis from naval support and delivering additional land forces to blockade him on land. The Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

attempted to dispute this control, but Admiral Thomas Graves was defeated in the key Battle of the Chesapeake on September 5. American and French armies that had massed outside New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

began moving south in late August, and arrived near Yorktown in mid-September. Deceptions about their movement successfully delayed attempts by Clinton to send more troops to Cornwallis.

The siege of Yorktown began on September 28, 1781. In a step that probably shortened the siege, Cornwallis decided to abandon parts of his outer defenses, and the besiegers successfully stormed two of his redoubts. When it became clear that his position was untenable, Cornwallis opened negotiations on October 17 and surrendered two days later. When the news reached London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

, the government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government i ...

of Lord North fell, and the following Rockingham ministry entered into peace negotiations. These culminated in the Treaty of Paris in 1783, in which King George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great B ...

recognized the independent United States of America

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territo ...

. Clinton and Cornwallis engaged in a public war of words defending their roles in the campaign, and British naval command also discussed the navy's shortcomings that led to the defeat.

Background

By December 1780, theAmerican Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

's North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and th ...

n theatres had reached a critical point. The Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies (the Thirteen Colonies) in the Revolutionary-era United States. It was formed by the Second Continental Congress after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, and was establis ...

had suffered major defeats earlier in the year, with its southern armies either captured or dispersed in the loss of Charleston and the Battle of Camden

The Battle of Camden (August 16, 1780), also known as the Battle of Camden Court House, was a major victory for the British in the Southern theater of the American Revolutionary War. On August 16, 1780, British forces under Lieutenant General ...

in the south, while the armies of George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

and the British commander-in-chief for North America, Sir Henry Clinton watched each other around New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

in the north. The national currency was virtually worthless, public support for the war, about to enter its sixth year, was waning, and army troops were becoming mutinous over pay and conditions. In the Americans' favor, provincial recruiting in the south had been checked with a severe blow at Kings Mountain in October.

French and American planning for 1781

Virginia had largely escaped military notice before 1779, when araid

Raid, RAID or Raids may refer to:

Attack

* Raid (military), a sudden attack behind the enemy's lines without the intention of holding ground

* Corporate raid, a type of hostile takeover in business

* Panty raid, a prankish raid by male college ...

destroyed much of the state's shipbuilding capacity and seized or destroyed large amounts of tobacco

Tobacco is the common name of several plants in the genus '' Nicotiana'' of the family Solanaceae, and the general term for any product prepared from the cured leaves of these plants. More than 70 species of tobacco are known, but the ...

, which was a significant trade item for the Americans.Ward, p. 867 Virginia's only defenses consisted of locally raised militia companies, and a naval force that had been virtually wiped out in the 1779 raid. The militia were under the overall direction of Continental Army General Baron von Steuben

Friedrich Wilhelm August Heinrich Ferdinand von Steuben (born Friedrich Wilhelm Ludolf Gerhard Augustin Louis von Steuben; September 17, 1730 – November 28, 1794), also referred to as Baron von Steuben (), was a Prussian military officer who p ...

, a prickly Prussian taskmaster who, although he was an excellent drillmaster, alienated not only his subordinates, but also had a difficult relationship with the state's governor, Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

. Steuben had established a training center in Chesterfield for new Continental Army recruits, and a "factory" in Westham

Westham is a large village and civil parish in the Wealden District of East Sussex, England. The village is adjacent to Pevensey five miles (8 km) north-east of Eastbourne. The parish consists of three settlements: Westham; Stone Cross; ...

for the manufacture and repair of weapons and ammunition.

French military planners had to balance competing demands for the 1781 campaign. After a series of unsuccessful attempts at cooperation with the Americans (leading to failed assaults on Newport, Rhode Island

Newport is an American seaside city on Aquidneck Island in Newport County, Rhode Island. It is located in Narragansett Bay, approximately southeast of Providence, south of Fall River, Massachusetts, south of Boston, and northeast of New Yor ...

, and Savannah, Georgia

Savannah ( ) is the oldest city in the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia and is the county seat of Chatham County, Georgia, Chatham County. Established in 1733 on the Savannah River, the city of Savannah became the Kingdom of Great Br ...

), they realized more active participation in North America was needed. However, they also needed to coordinate their actions with Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

, where there was potential interest in making an assault on the British stronghold of Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of Hispa ...

. It turned out that the Spanish were not interested in operations against Jamaica until after they had dealt with an expected British attempt to reinforce besieged Gibraltar, and merely wanted to be informed of the movements of the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greate ...

fleet.Dull, pp. 220–221

As the French fleet was preparing to depart Brest in March, several important decisions were made. The West Indies fleet, led by the

As the French fleet was preparing to depart Brest in March, several important decisions were made. The West Indies fleet, led by the Comte de Grasse

''Comte'' is the French, Catalan and Occitan form of the word 'count' (Latin: ''comes''); ''comté'' is the Gallo-Romance form of the word 'county' (Latin: ''comitatus'').

Comte or Comté may refer to:

* A count in French, from Latin ''comes''

* A ...

, after operations in the Windward Islands

french: Îles du Vent

, image_name =

, image_caption = ''Political'' Windward Islands. Clockwise: Dominica, Martinique, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, and Grenada.

, image_alt =

, locator_map =

, location = Caribbean Sea No ...

, was directed to go to Cap-Français (present-day Cap-Haïtien) to determine what resources would be required to assist Spanish operations. Due to a lack of transports, France also promised six million livres

The (; ; abbreviation: ₶.) was one of numerous currencies used in medieval France, and a unit of account (i.e., a monetary unit used in accounting) used in Early Modern France.

The 1262 monetary reform established the as 20 , or 80.88 g ...

to support the American war effort instead of providing additional troops. The French fleet at Newport was given a new commander, the Comte de Barras. De Barras was ordered to take the Newport fleet to harass British shipping off Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

and Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

, and the French army at Newport was ordered to combine with Washington's army outside New York. In orders that were deliberately not fully shared with General Washington, De Grasse was instructed to assist in North American operations after his stop at Cap-Français. The French general, the Comte de Rochambeau

Marshal Jean-Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, comte de Rochambeau, 1 July 1725 – 10 May 1807, was a French nobleman and general whose army played the decisive role in helping the United States defeat the British army at Yorktown in 1781 during the ...

was instructed to tell Washington that de Grasse ''might'' be able to assist, without making any commitment.Dull, p. 241 (Washington learned from John Laurens, stationed in Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Si ...

, that de Grasse had discretion to come north.)

The French fleet sailed from Brest on March 22. The British fleet was busy with preparations to resupply Gibraltar, and did not attempt to oppose the departure.Dull, p. 242 After the French fleet sailed, the packet ship ''Concorde'' sailed for Newport, carrying the Comte de Barras, Rochambeau's orders, and credits for the six million livres.Dull, p. 329 In a separate dispatch sent later, de Grasse also made two important requests. The first was that he be notified at Cap-Français of the situation in North America so that he could decide how he might be able to assist in operations there, and the second was that he be supplied with 30 pilots familiar with North American waters.

British planning for 1781

General Clinton never articulated a coherent vision for what the goals for British operations of the coming campaign season should be in the early months of 1781. Part of his problem lay in a difficult relationship with his naval counterpart in New York, the aging Vice Admiral

General Clinton never articulated a coherent vision for what the goals for British operations of the coming campaign season should be in the early months of 1781. Part of his problem lay in a difficult relationship with his naval counterpart in New York, the aging Vice Admiral Marriot Arbuthnot

Admiral Mariot Arbuthnot (1711 – 31 January 1794) was a British admiral, who commanded the Royal Navy's North American station during the American War for Independence.

Early life

A native of Weymouth, Dorset in England, Arbuthnot was the so ...

. Both men were stubborn, prone to temper, and had prickly personalities; due to repeated clashes, their working relationship had completely broken down. In the fall of 1780 Clinton had requested that either he or Arbuthnot be recalled; however, orders recalling Arbuthnot did not arrive until June. Until then, according to historian George Billias, "The two men could not act alone, and would not act together". Arbuthnot was replaced by Sir Thomas Graves, with whom Clinton had a somewhat better working relationship.

The British presence in the south consisted of the strongly fortified ports of Savannah, Georgia

Savannah ( ) is the oldest city in the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia and is the county seat of Chatham County, Georgia, Chatham County. Established in 1733 on the Savannah River, the city of Savannah became the Kingdom of Great Br ...

and Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the largest city in the U.S. state of South Carolina, the county seat of Charleston County, and the principal city in the Charleston–North Charleston metropolitan area. The city lies just south of the geographical midpoint o ...

, and a string of outposts in the interior of those two states. Although the strongest outposts were relatively immune to attack from the Patriot militia that were their only formal opposition in those states, the smaller outposts, as well as supply convoys and messengers, were often the target of militia commanders like Thomas Sumter

Thomas Sumter (August 14, 1734June 1, 1832) was a soldier in the Colony of Virginia militia; a brigadier general in the South Carolina militia during the American Revolution, a planter, and a politician. After the United States gained independe ...

and Francis Marion

Brigadier-General Francis Marion ( 1732 – February 27, 1795), also known as the Swamp Fox, was an American military officer, planter and politician who served during the French and Indian War and the Revolutionary War. During the Amer ...

. Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most d ...

had most recently been occupied in October 1780 by a force under the command of Major General Alexander Leslie

Alexander Leslie, 1st Earl of Leven (15804 April 1661) was a Scottish soldier in Swedish and Scottish service. Born illegitimate and raised as a foster child, he subsequently advanced to the rank of a Swedish Field Marshal, and in Scotland bec ...

, but Lieutenant General Charles, Earl Cornwallis, commanding the British southern army, had ordered them to South Carolina in November. To replace General Leslie at Portsmouth, General Clinton sent 1,600 troops under General Benedict Arnold

Benedict Arnold ( Brandt (1994), p. 4June 14, 1801) was an American military officer who served during the Revolutionary War. He fought with distinction for the American Continental Army and rose to the rank of major general before defect ...

(recently commissioned into the British Army as a brigadier) to Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth are ...

in late December.

British raiding in Virginia

Part of the fleet carrying General Arnold and his troops arrived in

Part of the fleet carrying General Arnold and his troops arrived in Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The Bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula (including the parts: the Eastern Shore of Maryland / ...

on December 30, 1780. Without waiting for the rest of the transports to arrive, Arnold sailed up the James River

The James River is a river in the U.S. state of Virginia that begins in the Appalachian Mountains and flows U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map , accessed April 1, 2011 to Chesap ...

and disembarked 900 troops at Westover, Virginia, on January 4. After an overnight forced march, he raided Richmond, the state capital, the next day, encountering only minimal militia resistance. After two more days of raiding in the area, they returned to their boats, and made sail for Portsmouth. Arnold established fortifications there, and sent his men out on raiding and foraging expeditions. The local militia were called out, but they were in such small numbers that the British presence could not be disputed. This did not prevent raiding expeditions from running into opposition, as some did in skirmishing at Waters Creek in March.

When news of Arnold's activities reached George Washington, he decided that a response was necessary. He wanted the French to send a naval expedition from their base in Newport, but the commanding admiral, Chevalier Destouches, refused any assistance until he received reports of serious storm damage to part of the British fleet on January 22.Carrington, p. 584 On February 9, Captain Arnaud de Gardeur de Tilley sailed from Newport with three ships (ship of the line

A ship of the line was a type of naval warship constructed during the Age of Sail from the 17th century to the mid-19th century. The ship of the line was designed for the naval tactic known as the line of battle, which depended on the two colu ...

''Eveille'' and frigate

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied somewhat.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed an ...

s ''Surveillante'' and ''Gentile''). When he arrived off Portsmouth four days later, Arnold withdrew his ships, which had shallower drafts than those of the French, up the Elizabeth River, where de Tilley could not follow.Linder, p. 11 De Tilley, after determining that the local militia were "completely insufficient" to attack Arnold's position, returned to Newport. On the way he captured HMS ''Romulus'', a frigate sent by the British from New York to investigate his movements.

Congress authorised a detachment of Continental forces to Virginia on February 20. Washington assigned command of the expedition to the

Congress authorised a detachment of Continental forces to Virginia on February 20. Washington assigned command of the expedition to the Marquis de Lafayette

Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de La Fayette (6 September 1757 – 20 May 1834), known in the United States as Lafayette (, ), was a French aristocrat, freemason and military officer who fought in the American Revolutio ...

, who left Peekskill, New York

Peekskill is a city in northwestern Westchester County, New York, United States, from New York City. Established as a village in 1816, it was incorporated as a city in 1940. It lies on a bay along the east side of the Hudson River, across from ...

the same day. His troops, numbering about 1,200, were three light regiments drawn from troops assigned to Continental regiments from New Jersey and New England; these regiments were led by Joseph Vose, Francis Barber

Francis Barber ( – 13 January 1801), born Quashey, was the Jamaican manservant of Samuel Johnson in London from 1752 until Johnson's death in 1784. Johnson made him his residual heir, with £70 () a year to be given him by Trustees, express ...

, and Jean-Joseph Sourbader de Gimat. Lafayette's force reached Head of Elk (present-day Elkton, Maryland

Elkton is a town in and the county seat of Cecil County, Maryland, United States. The population was 15,443 at the 2010 census. It was formerly called Head of Elk because it sits at the head of navigation on the Elk River, which flows into the n ...

, the northern navigable limit of Chesapeake Bay) on March 3.Carrington, p. 585 While awaiting transportation for his troops at Annapolis

Annapolis ( ) is the capital city of the U.S. state of Maryland and the county seat of, and only incorporated city in, Anne Arundel County. Situated on the Chesapeake Bay at the mouth of the Severn River, south of Baltimore and about east ...

, Lafayette traveled south, reaching Yorktown on March 14, to assess the situation.Clary, p. 295

American attempts at defense

De Tilley's expedition, and the strong encouragement of General Washington, who traveled to Newport to press the case, convinced Destouches to make a larger commitment. On March 8 he sailed with his entire fleet (7 ships of the line and several frigates, including the recently captured ''Romulus''), carrying French troops to join with Lafayette's in Virginia. Admiral Arbuthnot, alerted to his departure, sailed on March 10 after sending Arnold a dispatch warning of the French movement. Arbuthnot, whose copper-clad ships could sail faster than those of Destouches, reachedCape Henry

Cape Henry is a cape on the Atlantic shore of Virginia located in the northeast corner of Virginia Beach. It is the southern boundary of the entrance to the long estuary of the Chesapeake Bay.

Across the mouth of the bay to the north is Cape Ch ...

on March 16, just ahead of the French fleet. The ensuing battle was largely indecisive, but left Arbuthnot free to enter Lynnhaven Bay and control access to Chesapeake Bay; Destouches returned to Newport.Ward, p. 870 Lafayette saw the British fleet, and pursuant to orders, made preparations to return his troops to the New York area. By early April he had returned to Head of Elk, where he received orders from Washington to stay in Virginia.Clary, p. 296Carrington, p. 586

The departure of Destouches' fleet from Newport had prompted General Clinton to send Arnold reinforcements. In the wake of Arbuthnot's sailing he sent transports carrying about 2,000 men under the command of General

The departure of Destouches' fleet from Newport had prompted General Clinton to send Arnold reinforcements. In the wake of Arbuthnot's sailing he sent transports carrying about 2,000 men under the command of General William Phillips William Phillips may refer to:

Entertainment

* William Phillips (editor) (1907–2002), American editor and co-founder of ''Partisan Review''

* William T. Phillips (1863–1937), American author

* William Phillips (director), Canadian film-make ...

to the Chesapeake. These joined Arnold at Portsmouth on March 27.Lockhart, p. 247 Phillips, as senior commander, took over the force and resumed raiding, targeting Petersburg and Richmond. By this time, Baron von Steuben and Peter Muhlenberg, the militia commanders in Virginia, felt they had to make a stand to maintain morale despite the inferior strength of their troops. They established a defensive line in Blandford, near Petersburg (Blandford is now a part of the city of Petersburg), and fought a disciplined but losing action on April 25. Von Steuben and Muhlenberg retreated before the advance of Phillips, who hoped to again raid Richmond. However, Lafayette made a series of forced marches, and reached Richmond on April 29, just hours before Phillips.

Cornwallis and Lafayette

To counter the British threat in the Carolinas, Washington had sent Major General

To counter the British threat in the Carolinas, Washington had sent Major General Nathanael Greene

Nathanael Greene (June 19, 1786, sometimes misspelled Nathaniel) was a major general of the Continental Army in the American Revolutionary War. He emerged from the war with a reputation as General George Washington's most talented and dependab ...

, one of his best strategists, to rebuild the American army in North Carolina

North Carolina () is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 28th largest and List of states and territories of the United ...

after the defeat at Camden. General Cornwallis, leading the British troops in the south, wanted to deal with him and gain control over the state. Greene divided his inferior force, sending part of his army under Daniel Morgan

Daniel Morgan (1735–1736July 6, 1802) was an American pioneer, soldier, and politician from Virginia. One of the most respected battlefield tacticians of the American Revolutionary War of 1775–1783, he later commanded troops during the sup ...

to threaten the British post at Ninety Six, South Carolina

Ninety Six is a town in Greenwood County, South Carolina, United States. The population was 1,998 at the 2010 census.

Geography

Ninety Six is located in eastern Greenwood County at (34.173211, -82.021710). South Carolina Highway 34 passes throu ...

. Cornwallis sent Banastre Tarleton after Morgan, who almost wiped out Tarleton's command in the January Battle of Cowpens, and almost captured Tarleton in the process. This action was followed by what has been called the "race to the Dan," in which Cornwallis gave chase to Morgan and Greene in an attempt to catch them before they reunited their forces. When Greene successfully crossed the Dan River

The Dan River flows in the U.S. states of North Carolina and Virginia. It rises in Patrick County, Virginia, and crosses the state border into Stokes County, North Carolina. It then flows into Rockingham County. From there it flows back i ...

and entered Virginia, Cornwallis, who had stripped his army of most of its baggage, gave up the pursuit. However, Greene received reinforcements and supplies, recrossed the Dan, and returned to Greensboro, North Carolina

Greensboro (; formerly Greensborough) is a city in and the county seat of Guilford County, North Carolina, United States. It is the List of municipalities in North Carolina, third-most populous city in North Carolina after Charlotte, North Car ...

to do battle with Cornwallis. The earl won the battle, but Greene was able to withdraw with his army intact, and the British suffered enough casualties that Cornwallis was forced to retreat to Wilmington for reinforcement and resupply. Greene then went on to regain control over most of South Carolina and Georgia. Cornwallis, in violation of orders but also in the absence of significant strategic direction by General Clinton, decided to take his army, now numbering just 1,400 men, into Virginia on April 25; it was the same day that Phillips and von Steuben fought at Blandford.

Phillips, after Lafayette beat him to Richmond, turned back east, continuing to destroy military and economic targets in the area. On May 7, Phillips received a dispatch from Cornwallis, ordering him to Petersburg to effect a junction of their forces; three days later, Phillips arrived in Petersburg.Johnston, p. 34 Lafayette briefly cannonaded the British position there, but did not feel strong enough to actually make an attack.Campbell, p. 721 On May 13, Phillips died of a fever, and Arnold retook control of the force.Campbell, p. 722 This caused some grumbling amongst the men, since Arnold was not particularly well respected. While waiting for Cornwallis, the forces of Arnold and Lafayette watched each other. Arnold attempted to open communications with the marquis (who had orders from Washington to summarily hang Arnold), but the marquis returned his letters unopened.Clary, p. 302 Cornwallis arrived in Petersburg on May 19, prompting Lafayette, who commanded under 1,000 Continentals and about 2,000 militia, to retreat to Richmond.Clary, p. 305Campbell, p. 726 Further British reinforcements led by the Ansbacher Colonel von Voigt arrived from New York shortly after, raising the size of Cornwallis's army to more than 7,000.Wickwire, p. 326

Cornwallis, after dispatching General Arnold back to New York, then set out to follow General Clinton's most recent orders to Phillips.Russell, p. 256Carrington, p. 595 These instructions were to establish a fortified base and raid rebel military and economic targets in Virginia. Cornwallis decided that he had to first deal with the threat posed by Lafayette, so he set out in pursuit of the marquis. Lafayette, clearly outnumbered, retreated rapidly toward Fredericksburg to protect an important supply depot there,Clary, p. 306 while von Steuben retreated to Point of Fork (present-day

Cornwallis, after dispatching General Arnold back to New York, then set out to follow General Clinton's most recent orders to Phillips.Russell, p. 256Carrington, p. 595 These instructions were to establish a fortified base and raid rebel military and economic targets in Virginia. Cornwallis decided that he had to first deal with the threat posed by Lafayette, so he set out in pursuit of the marquis. Lafayette, clearly outnumbered, retreated rapidly toward Fredericksburg to protect an important supply depot there,Clary, p. 306 while von Steuben retreated to Point of Fork (present-day Columbia, Virginia

Columbia, formerly known as Point of Fork, is an unincorporated community and census designated place in Fluvanna County, Virginia, United States, at the confluence of the James and Rivanna rivers. Following a referendum, Columbia was dissolved ...

), where militia and Continental Army trainees had gathered with supplies pulled back before the raiding British. Cornwallis reached the Hanover County courthouse on June 1, and, rather than send his whole army after Lafayette, detached Banastre Tarleton and John Graves Simcoe

John Graves Simcoe (25 February 1752 – 26 October 1806) was a British Army general and the first lieutenant governor of Upper Canada from 1791 until 1796 in southern Ontario and the watersheds of Georgian Bay and Lake Superior. He founded Yor ...

on separate raiding expeditions.Morrissey, p. 39

Tarleton, his British Legion

The Royal British Legion (RBL), formerly the British Legion, is a British charity providing financial, social and emotional support to members and veterans of the British Armed Forces, their families and dependants, as well as all others in ne ...

reduced by the debacle at Cowpens, rode rapidly with a small force to Charlottesville

Charlottesville, colloquially known as C'ville, is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia. It is the county seat of Albemarle County, which surrounds the city, though the two are separate legal entities. It is named after Queen ...

, where he captured several members of the Virginia legislature. He almost captured Governor Jefferson as well, but had to content himself with several bottles of wine from Jefferson's estate at Monticello

Monticello ( ) was the primary plantation of Founding Father Thomas Jefferson, the third president of the United States, who began designing Monticello after inheriting land from his father at age 26. Located just outside Charlottesville, V ...

. Simcoe went to Point of Fork to deal with von Steuben and the supply depot. In a brief skirmish on June 5, von Steuben's forces, numbering about 1,000, suffered 30 casualties, but they had withdrawn most of the supplies across the river. Simcoe, who only had about 300 men, then exaggerated the size of his force by lighting a large number of campfires; this prompted von Steuben to withdraw from Point of Fork, leaving the supplies to be destroyed by Simcoe the next day.Clary, p. 307

Lafayette, in the meantime, was expecting the imminent arrival of long-delayed reinforcements. Several battalions of Pennsylvania Continentals under Brigadier General Anthony Wayne

Anthony Wayne (January 1, 1745 – December 15, 1796) was an American soldier, officer, statesman, and one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. He adopted a military career at the outset of the American Revolutionary War, where his mil ...

had also been authorised by Congress for service in Virginia in February. However, Wayne had to deal with the aftereffects of a mutiny in January that nearly wiped out the Pennsylvania Line

The Pennsylvania Line was a formation within the Continental Army. The term "Pennsylvania Line" referred to the quota of numbered infantry regiments assigned to Pennsylvania at various times by the Continental Congress. These, together with simila ...

as a fighting force, and it was May before he had rebuilt the line and begun the march to Virginia. Even then, there was a great deal of mistrust between Wayne and his men; Wayne had to keep his ammunition and bayonets under lock and key except when they were needed. Although Wayne was ready to march on May 19, the force's departure was delayed by a day because of a renewed threat of mutiny after the units were paid with devalued Continental dollars.Spears, 178 Lafayette and Wayne's 800 men joined forces at Raccoon Ford on the Rappahannock River

The Rappahannock River is a river in eastern Virginia, in the United States, approximately in length.U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed April 1, 2011 It traverses the entir ...

on June 10.Clary, p. 308 A few days later, Lafayette was further reinforced by 1,000 militia under the command of William Campbell.Ward, p. 874

After the successful raids of Simcoe and Tarleton, Cornwallis began to make his way east toward Richmond and Williamsburg, almost contemptuously ignoring Lafayette in his movements. Lafayette, his force grown to about 4,500, was buoyed in confidence, and began to edge closer to the earl's army. By the time Cornwallis reached Williamsburg on June 25, Lafayette was away, at Bird's Tavern. That day, Lafayette learned that Simcoe's Queen's Rangers were at some remove from the main British force, so Lafayette sent some cavalry and light infantry to intercept them. This precipitated a skirmish at Spencer's Ordinary where each side believed the other to be within range of its main army.

After the successful raids of Simcoe and Tarleton, Cornwallis began to make his way east toward Richmond and Williamsburg, almost contemptuously ignoring Lafayette in his movements. Lafayette, his force grown to about 4,500, was buoyed in confidence, and began to edge closer to the earl's army. By the time Cornwallis reached Williamsburg on June 25, Lafayette was away, at Bird's Tavern. That day, Lafayette learned that Simcoe's Queen's Rangers were at some remove from the main British force, so Lafayette sent some cavalry and light infantry to intercept them. This precipitated a skirmish at Spencer's Ordinary where each side believed the other to be within range of its main army.

Allied decisions

While Lafayette, Arnold, and Phillips manoeuvred in Virginia, the allied leaders, Washington and Rochambeau, considered their options. On May 6 the ''Concorde'' arrived in Boston, and two days later Washington and Rochambeau were informed of the arrival of de Barras as well as the vital dispatches and funding. On May 23 and 24, Washington and Rochambeau held a conference at

While Lafayette, Arnold, and Phillips manoeuvred in Virginia, the allied leaders, Washington and Rochambeau, considered their options. On May 6 the ''Concorde'' arrived in Boston, and two days later Washington and Rochambeau were informed of the arrival of de Barras as well as the vital dispatches and funding. On May 23 and 24, Washington and Rochambeau held a conference at Wethersfield, Connecticut

Wethersfield is a town located in Hartford County, Connecticut. It is located immediately south of Hartford along the Connecticut River. Its population was 27,298 at the time of the 2020 census.

Many records from colonial times spell the nam ...

where they discussed what steps to take next.Grainger, p. 38 They agreed that, pursuant to his orders, Rochambeau would move his army from Newport to the Continental Army camp at White Plains, New York

(Always Faithful)

, image_seal = WhitePlainsSeal.png

, seal_link =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name =

, subdivision_type1 = State

, subdivision_name1 =

, subdivis ...

. They also decided to send dispatches to de Grasse outlining two possible courses of action. Washington favored the idea of attacking New York, while Rochambeau favored action in Virginia, where the British were less well established. Washington's letter to de Grasse outlined these two options; Rochambeau, in a private note, informed de Grasse of his preference. Lastly, Rochambeau convinced de Barras to hold his fleet in readiness to assist in either operation, rather than taking it out on expeditions to the north as he had been ordered.Grainger, p. 41 The ''Concorde'' sailed from Newport on June 20, carrying dispatches from Washington, Rochambeau, and de Barras, as well as the pilots de Grasse had requested.Dull, p. 242 The French army left Newport in June, and joined Washington's army at Dobb's Ferry, New York on July 7. From there, Washington and Rochambeau embarked on an inspection tour of the British defenses around New York while they awaited word from de Grasse.

De Grasse had a somewhat successful campaign in the West Indies. His forces successfully captured Tobago in June after a minor engagement with the British fleet. Beyond that, he and British Admiral George Brydges Rodney avoided significant engagement. De Grasse arrived at Cap-Français on July 16, where the ''Concorde'' awaited him.Linder, p. 14 He immediately engaged in negotiations with the Spanish. He informed them of his intent to sail north, but promised to return by November to assist in Spanish operations in exchange for critical Spanish cover while he sailed north. From them he secured the promise to protect French commerce and territories so that he could bring north his entire fleet, 28 ships of the line.Larrabee, p. 156 In addition to his fleet, he took on 3,500 troops under the command of the Marquis de St. Simon, and appealed to the Spanish in Havana

Havana (; Spanish: ''La Habana'' ) is the capital and largest city of Cuba. The heart of the La Habana Province, Havana is the country's main port and commercial center.

for funds needed to pay Rochambeau's troops.Dull, pp. 243–244 On July 28, he sent the ''Concorde'' back to Newport, informing Washington, Rochambeau, and de Barras that he expected to arrive in the Chesapeake at the end of August, and would need to leave by mid-October. He sailed from Cap-Français on August 5, beginning a deliberately slow route north through a little-used channel in the Bahamas

The Bahamas (), officially the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, is an island country within the Lucayan Archipelago of the West Indies in the North Atlantic. It takes up 97% of the Lucayan Archipelago's land area and is home to 88% of the a ...

.

British decisions

The movement of the French army to the New York area caused General Clinton a great deal of concern; letters written by Washington that Clinton had intercepted suggested that the allies were planning an attack on New York. Beginning in June he wrote a series of letters to Cornwallis containing a confusing and controversial set of ruminations, suggestions, and recommendations, that only sometimes contained concrete and direct orders.Grainger, p. 44 Some of these letters were significantly delayed in reaching Cornwallis, complicating the exchange between the two. On June 11 and 15, apparently in reaction to the threat to New York, Clinton requested Cornwallis to fortify either Yorktown or Williamsburg, and send any troops he could spare back to New York. Cornwallis received these letters at Williamsburg on June 26. He and an engineer inspected Yorktown, which he found to be defensively inadequate. He wrote a letter to Clinton indicating that he would move to Portsmouth in order to send troops north with transports available there.James River

The James River is a river in the U.S. state of Virginia that begins in the Appalachian Mountains and flows U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map , accessed April 1, 2011 to Chesap ...

and march to Portsmouth. Lafayette's scouts observed the motion, and he realised the British force would be vulnerable during the crossing. He advanced his army to the Green Spring Plantation

Green Spring Plantation in James City County about west of Williamsburg, was the 17th century plantation of one of the more popular governors of Colonial Virginia in North America, Sir William Berkeley, and his wife, Frances Culpeper Berkel ...

, and, based on intelligence that only the British rear guard was left at the crossing, sent General Wayne forward to attack them on July 6. In reality, the earl had laid a clever trap. Crossing only his baggage and some troops to guard them, he sent "deserters" to falsely inform Lafayette of the situation. In the Battle of Green Spring, General Wayne managed to escape the trap, but with significant casualties and the loss of two field pieces. Cornwallis then crossed the river, and marched his army to Suffolk

Suffolk () is a ceremonial county of England in East Anglia. It borders Norfolk to the north, Cambridgeshire to the west and Essex to the south; the North Sea lies to the east. The county town is Ipswich; other important towns include ...

.

Cornwallis again detached Tarleton on a raid into central Virginia. Tarleton's raid was based on intelligence that supplies might be intercepted that were en route to General Greene. The raid, in which Tarleton's force rode in four days, was a failure, since supplies had already been moved.Clary, p. 321 (During this raid, some of Tarleton's men were supposedly in a minor skirmish with Peter Francisco, one of the American heroes of Guilford Court House.) Cornwallis received another letter from General Clinton while at Suffolk, dated June 20, stating that the forces to be embarked were to be used for an attack against Philadelphia.

When Cornwallis reached Portsmouth, he began embarking troops pursuant to Clinton's orders. On July 20, with some transports almost ready to sail, new orders arrived that countermanded the previous ones. In the most direct terms, Clinton ordered him to establish a fortified deep-water port, using as much of his army as he thought necessary. Clinton took this decision because the navy had long been dissatisfied with New York as a naval base, firstly because sand bars obstructed the entrance to the Hudson River, damaging the hulls of the larger ships; and secondly because the river often froze in winter, imprisoning vessels inside the harbour. Arbuthnot had recently been replaced and to show his satisfaction at this development, Clinton now acceded to the Navy's request, despite Cornwallis's warning that the Chesapeake's open bays and navigable rivers meant that any base there "will always be exposed to sudden French attack." It was to prove a fatal error of judgement by Clinton, since the need to defend the new facility denied Cornwallis any freedom of movement. Nevertheless, having inspected Portsmouth and found it less favourable than Yorktown, Cornwallis wrote to Clinton informing him that he would fortify Yorktown.

Lafayette was alerted on July 26 that Cornwallis was embarking his troops, but lacked intelligence about their eventual destination, and began manoeuvring his troops to cover some possible landing points. On August 6 he learned that Cornwallis had landed at Yorktown and was fortifying it and

When Cornwallis reached Portsmouth, he began embarking troops pursuant to Clinton's orders. On July 20, with some transports almost ready to sail, new orders arrived that countermanded the previous ones. In the most direct terms, Clinton ordered him to establish a fortified deep-water port, using as much of his army as he thought necessary. Clinton took this decision because the navy had long been dissatisfied with New York as a naval base, firstly because sand bars obstructed the entrance to the Hudson River, damaging the hulls of the larger ships; and secondly because the river often froze in winter, imprisoning vessels inside the harbour. Arbuthnot had recently been replaced and to show his satisfaction at this development, Clinton now acceded to the Navy's request, despite Cornwallis's warning that the Chesapeake's open bays and navigable rivers meant that any base there "will always be exposed to sudden French attack." It was to prove a fatal error of judgement by Clinton, since the need to defend the new facility denied Cornwallis any freedom of movement. Nevertheless, having inspected Portsmouth and found it less favourable than Yorktown, Cornwallis wrote to Clinton informing him that he would fortify Yorktown.

Lafayette was alerted on July 26 that Cornwallis was embarking his troops, but lacked intelligence about their eventual destination, and began manoeuvring his troops to cover some possible landing points. On August 6 he learned that Cornwallis had landed at Yorktown and was fortifying it and Gloucester Point

Gloucester Point is a census-designated place (CDP) in Gloucester County, Virginia, United States. The population was 9,402 at the 2010 census. It is home to the College of William & Mary's Virginia Institute of Marine Science, a graduate school ...

just across the York River.

Convergence on Yorktown

Admiral Rodney had been warned that de Grasse was planning to take at least part of his fleet north. Although he had some clues that he might take his whole fleet (he was aware of the number of pilots de Grasse had requested, for example), he assumed that de Grasse would not leave the French convoy at Cap-Français, and that part of his fleet would escort it to France as Admiral Guichen had done the previous year. Rodney made his dispositions accordingly, balancing the likely requirements of the fleet in North America with the need to protect Britain's own trade convoys. Sixteen of his twenty-one battleships, therefore, were to sail with Hood in pursuit of de Grasse to the Chesapeake before proceeding to New York. Rodney, who was ill, meanwhile took three other battleships back to England, two as merchant escorts, leaving his remaining two in dock for repairs. Hood was well satisfied with these arrangements, telling a colleague that his fleet was "equal fully to defeat any designs of the enemy, let de Grasse bring or send what number of ships he might in aid of Barras." What neither Rodney or Hood knew was de Grasse's last minute decision to take his entire fleet to North America, thus ensuring a French superiority of three to two in battleship strength. Blissfully unaware of this development, Hood eventually sailed from Antigua on August 10, five days after de Grasse. During the voyage, one of his smaller ships carrying intelligence about the American pilots was captured by a privateer, thus further depriving the British in New York of valuable information. Hood himself, following the direct route, reached the Chesapeake on August 25, and found the entrance to the bay empty. He then sailed on to New York to meet with Admiral Sir Thomas Graves, in command of the New York station following Arbuthnot's departure. On August 14 General Washington learned of de Grasse's decision to sail for the Chesapeake. The next day he reluctantly abandoned the idea of assaulting New York, writing that " tters having now come to a crisis and a decisive plan to be determined on, I was obliged ... to give up all idea of attacking New York..."Ketchum, p. 151 The combined Franco-American army began moving south on August 19, engaging in several tactics designed to fool Clinton about their intentions. Some forces were sent on a route along the New Jersey shore, and ordered to make camp preparations as if preparing for an attack on Staten Island. The army also carried landing craft to lend verisimilitude to the idea. Washington sent orders to Lafayette to prevent Cornwallis from returning to North Carolina; he did not learn that Cornwallis was entrenching at Yorktown until August 30. Two days later the army was passing through Philadelphia; another mutiny was averted there when funds were procured for troops that threatened to stay until they were paid.

On August 14 General Washington learned of de Grasse's decision to sail for the Chesapeake. The next day he reluctantly abandoned the idea of assaulting New York, writing that " tters having now come to a crisis and a decisive plan to be determined on, I was obliged ... to give up all idea of attacking New York..."Ketchum, p. 151 The combined Franco-American army began moving south on August 19, engaging in several tactics designed to fool Clinton about their intentions. Some forces were sent on a route along the New Jersey shore, and ordered to make camp preparations as if preparing for an attack on Staten Island. The army also carried landing craft to lend verisimilitude to the idea. Washington sent orders to Lafayette to prevent Cornwallis from returning to North Carolina; he did not learn that Cornwallis was entrenching at Yorktown until August 30. Two days later the army was passing through Philadelphia; another mutiny was averted there when funds were procured for troops that threatened to stay until they were paid.

Admiral de Barras sailed with his fleet from Newport, carrying the French siege equipment, on August 25. He sailed a route that deliberately took him away from the coast to avoid encounters with the British. De Grasse reached the Chesapeake on August 30, five days after Hood. He immediately debarked the troops from his fleet to assist Lafayette in blockading Cornwallis, and stationed some his ships to blockade the York and James Rivers.

News of de Barras' sailing reached New York on August 28, where Graves, Clinton, and Hood were meeting to discuss the possibility of making an attack on the French fleet in Newport, since the French army was no longer there to defend it. Clinton had still not realized that Washington was marching south, something he did not have confirmed until September 2. When they learned of de Barras' departure they immediately concluded that de Grasse must be headed for the Chesapeake (but still did not know of his strength). Graves sailed from New York on August 31 with 19 ships of the line; Clinton wrote Cornwallis to warn him that Washington was coming, and that he would send 4,000 reinforcements.

Admiral de Barras sailed with his fleet from Newport, carrying the French siege equipment, on August 25. He sailed a route that deliberately took him away from the coast to avoid encounters with the British. De Grasse reached the Chesapeake on August 30, five days after Hood. He immediately debarked the troops from his fleet to assist Lafayette in blockading Cornwallis, and stationed some his ships to blockade the York and James Rivers.