Yellow people on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Identifying

p. 172f.

This division in Rabbi Eliezer and other rabbinical texts is received by

Following

Following

This is due to historic negative associations of terms like "Yellow" (for East Asians) and "Red" (for Native Americans) with racism. However, some Asian Americans and Native Americans have tried to reclaim these color terms by self-identifying as "Yellow" and "Red", respectively. Though not an official color or racial designation in the United States census, "

human races

A race is a categorization of humans based on shared physical or social qualities into groups generally viewed as distinct within a given society. The term came into common usage during the 1500s, when it was used to refer to groups of variou ...

in terms of skin color

Human skin color ranges from the darkest brown to the lightest hues. Differences in skin color among individuals is caused by variation in pigmentation, which is the result of genetics (inherited from one's biological parents and or individu ...

, at least as one among several physiological characteristics, has been common since antiquity. Such divisions appeared in rabbinical literature and in early modern scholarship, usually dividing humankind into four or five categories, with color-based labels: red, yellow, black, white, and sometimes brown. It was long recognized that the number of categories is arbitrary and subjective, and different ethnic groups were placed in different categories at different points in time. François Bernier

François Bernier (25 September 162022 September 1688) was a French physician and traveller. He was born in Joué-Etiau in Anjou. He stayed (14 October 165820 February 1670) for around 12 years in India.

His 1684 publication "Nouvel ...

(1684) doubted the validity of using skin color as a racial characteristic, and Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended ...

(1871) emphasized the gradual differences between categories. Today there is broad agreement among scientists that typological conceptions of race have no scientific basis.

History

Antiquity to 1600s

Categorization of racial groups by reference to skin color is common in classical antiquity. For example, it is found in e.g. ''Physiognomica

''Physiognomonics'' ( el, Φυσιογνωμονικά; la, Physiognomonica) is an Ancient Greek pseudo-Aristotelian treatise on physiognomy attributed to Aristotle (and part of the Corpus Aristotelicum).

Ancient physiognomy before the ''Physi ...

'', a Greek treatise dated to c. 300 BC.

The transmission of the "color terminology" for race from antiquity to early anthropology in 17th century Europe took place via rabbinical literature. Specifically, Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer

Pirkei de-Rabbi Eliezer (also Pirkei DeRabbi Eliezer; Aramaic: פרקי דרבי אליעזר, or פרקים דרבי אליעזר, Chapters of Rabbi Eliezer; abbreviated PdRE) is an aggadic-midrashic work on the Torah containing exegesis and re ...

(a medieval rabbinical text dated roughly to between the 7th to 12th centuries) contains the division of mankind into three groups based on the three sons of Noah

The Generations of Noah, also called the Table of Nations or Origines Gentium, is a genealogy of the sons of Noah, according to the Hebrew Bible (Genesis ), and their dispersion into many lands after the Flood, focusing on the major known socie ...

, viz. Shem

Shem (; he, שֵׁם ''Šēm''; ar, سَام, Sām) ''Sḗm''; Ge'ez: ሴም, ''Sēm'' was one of the sons of Noah in the book of Genesis and in the book of Chronicles, and the Quran.

The children of Shem were Elam, Ashur, Arphaxad, Lu ...

, Ham

Ham is pork from a leg cut that has been preserved by wet or dry curing, with or without smoking."Bacon: Bacon and Ham Curing" in ''Chambers's Encyclopædia''. London: George Newnes, 1961, Vol. 2, p. 39. As a processed meat, the term "ham ...

and Japheth

Japheth ( he, יֶפֶת ''Yép̄eṯ'', in pausa ''Yā́p̄eṯ''; el, Ἰάφεθ '; la, Iafeth, Iapheth, Iaphethus, Iapetus) is one of the three sons of Noah in the Book of Genesis, in which he plays a role in the story of Noah's drunken ...

:

:"He oahespecially blessed Shem and his sons, (making them) Black but comely [], and he gave them the habitable earth. He blessed Ham and his sons, (making them) black like the raven [], and he gave them as an inheritance the coast of the sea. He blessed Japheth and his sons, (making) them entirely white [], and he gave them for an inheritance the desert and its fields" (trans. Gerald Friedlander 1916p. 172f.

This division in Rabbi Eliezer and other rabbinical texts is received by

Georgius Hornius Georgius Hornius (Georg Horn, 1620–1670) was a German historian and geographer, professor of history at Leiden University from 1653 until his death.

Life

He was born in Kemnath, Upper Palatinate (at the time part of the Electoral Palatinate ...

(1666). In Hornius' scheme, the Japhetites

The term Japhetites (in adjective form Japhethitic or Japhetic) refers to the descendents of Japheth, one of the three sons of Noah in the Bible. The term has been adopted in ethnological and linguistic writing from the 18th to the 20th centu ...

(identified as Scythians

The Scythians or Scyths, and sometimes also referred to as the Classical Scythians and the Pontic Scythians, were an ancient Eastern

* : "In modern scholarship the name 'Sakas' is reserved for the ancient tribes of northern and eastern Cent ...

, an Iranic ethnic group and Celts

The Celts (, see pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples () are. "CELTS location: Greater Europe time period: Second millennium B.C.E. to present ancestry: Celtic a collection of Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancient ...

) are "white" (), the Aethiopia

Ancient Aethiopia, ( gr, Αἰθιοπία, Aithiopía; also known as Ethiopia) first appears as a geographical term in classical documents in reference to the upper Nile region of Sudan, as well as certain areas south of the Sahara desert. Its ...

ns and Chamae are "black" (), and the Indians and Semites

Semites, Semitic peoples or Semitic cultures is an obsolete term for an ethnic, cultural or racial group.Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

, following ''Mishnah Sanhedrin

The Sanhedrin ( Hebrew and Aramaic: סַנְהֶדְרִין; Greek: , '' synedrion'', 'sitting together,' hence ' assembly' or 'council') was an assembly of either 23 or 71 elders (known as " rabbis" after the destruction of the Second Temp ...

'', are exempt from the classification being neither black nor white but "light brown" (, the color of boxwood).

François Bernier

François Bernier (25 September 162022 September 1688) was a French physician and traveller. He was born in Joué-Etiau in Anjou. He stayed (14 October 165820 February 1670) for around 12 years in India.

His 1684 publication "Nouvel ...

in a short article published anonymously in 1684 moves away from the "Noahide" classification, proposes to consider large subgroups of mankind based not on geographical distribution but on physiological differences. Writing in French, Bernier uses the term , or synonymously "kind, species", where Hornius had used "tribe" or "people". Bernier explicitly rejects a categorization based on skin color, arguing that the dark skin of Indians is due to exposure to the Sun only, and that the yellowish colour of some Asians, while a genuine feature, is not sufficient to establish a separate category. Instead his first category comprises most of Europe, the Near East and North Africa, including populations in the Nile Valley and the Indian peninsula he describes as being of a near "black" skin tone due to the effect of the sun. His second category includes most of Sub-Saharan Africa, again not exclusively based on skin colour but on physiological features such as the shape of nose and lips. His third category includes Southeast Asia, China and Japan as well as part of Tatarstan (Central Asia and eastern Muscovy). Members of this category are described as white, the categorization being based on facial features rather than skin colour. His fourth category are the Lapps (''Lappons''), described as a savage race with faces reminiscent of bears (but for which the author admits to rely on hearsay). Finally, the natives of the Americas are considered as a fifth category, described as of "olive

The olive, botanical name ''Olea europaea'', meaning 'European olive' in Latin, is a species of small tree or shrub in the family Oleaceae, found traditionally in the Mediterranean Basin. When in shrub form, it is known as ''Olea europaea'' ' ...

" () skin tone. The author furthermore considers the possible addition of more categories, specifically the "blacks of the Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( af, Kaap die Goeie Hoop ) ;''Kaap'' in isolation: pt, Cabo da Boa Esperança is a rocky headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is ...

", which seemed to him to be of significantly different build from most other populations below the Sahara.

Early Modern physical anthropology

In the 1730s,Carl Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (; 23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after his ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné Blunt (2004), p. 171. (), was a Swedish botanist, zoologist, taxonomist, and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, ...

in his introduction of systematic taxonomy recognized four main human subspecies

Human taxonomy is the classification of the human species (systematic name ''Homo sapiens'', Latin: "wise man") within zoological taxonomy. The systematic genus, ''Homo'', is designed to include both anatomically modern humans and extinct va ...

, termed

(Americans), (Europeans), (Asians) and (Africans). The physical appearance of each type is briefly described, including colour adjectives referring to skin and hair colour: "red" and "black hair" for Americans, "white" and "yellowish

Varieties of the color yellow may differ in hue, chroma (also called saturation, intensity, or colorfulness) or lightness (or value, tone, or brightness), or in two or three of these qualities. Variations in value are also called tints and shad ...

hair" for Europeans, "yellowish, sallow", "swarthy hair" for Asians,

and "black", "coal-black hair" for Africans.

The views of Johann Friedrich Blumenbach

Johann Friedrich Blumenbach (11 May 1752 – 22 January 1840) was a German physician, naturalist, physiologist, and anthropologist. He is considered to be a main founder of zoology and anthropology as comparative, scientific disciplines. He ...

on the categorization of the major races of mankind developed over the course of the 1770s to 1820s. He introduced a four-fold division in 1775, extended to five in 1779, later borne out in his work on craniology

Phrenology () is a pseudoscience which involves the measurement of bumps on the skull to predict mental traits.Wihe, J. V. (2002). "Science and Pseudoscience: A Primer in Critical Thinking." In ''Encyclopedia of Pseudoscience'', pp. 195–203. C ...

(''Decas craniorum'', published during 1790–1828). He also used color as the name or main label of the races but as part of the description of their physiology. Blumenbach does not name his five groups in 1779 but gives their geographic distribution. The color adjectives used in 1779 are "white" (Caucasian race

The Caucasian race (also Caucasoid or Europid, Europoid) is an obsolete racial classification of human beings based on a now-disproven theory of biological race. The ''Caucasian race'' was historically regarded as a biological taxon which, de ...

), "yellow-brown" ( Mongolian race), "black" ( Aethiopian race), "copper-red" ( American race) and "black-brown" ( Malayan race). Blumenbach belonged to a group known as the Göttingen school of history

Göttingen (, , ; nds, Chöttingen) is a university city in Lower Saxony, central Germany, the capital of the eponymous district. The River Leine runs through it. At the end of 2019, the population was 118,911.

General information

The or ...

, which helped to popularize his ideas.

Blumenbach's division and choice of color-adjectives remained influential throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, with variation depending on author. René Lesson

René-Primevère Lesson (20 March 1794 – 28 April 1849) was a French surgeon, naturalist, ornithologist, and herpetologist.

Biography

Lesson was born at Rochefort, and entered the Naval Medical School in Rochefort at the age of sixteen. H ...

in 1847 presented a division into six groups based on simple color adjectives: White (Caucasian), Dusky (Indian), Orange-colored (Malay), Yellow (Mongoloid), Red (Carib and American), Black (Negroid). According to Barkhaus (2006) it was the adoption of both the colour terminology and the French term by Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (, , ; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German philosopher and one of the central Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works in epistemology, metaphysics, ethics, and ...

in 1775 which proved influential. Kant published an essay ''Von den verschiedenen Racen der Menschen'' "On the diverse races of mankind" in 1775, based on the system proposed by Buffon, ''Histoire Naturelle

The ''Histoire Naturelle, générale et particulière, avec la description du Cabinet du Roi'' (; en, Natural History, General and Particular, with a Description of the King's Cabinet, italic=yes) is an encyclopaedic collection of 36 large (qu ...

'', in which he recognized four groups, a "white" European race (), a "black" Negroid race (), a copper-red Kalmyk race () and an olive-yellow Indian race ().

Two historical anthropologists favored a binary racial classification system that divided people into a light skin and dark skin categories. 18th-century anthropologist Christoph Meiners

Christoph Meiners (31 July 1747 – 1 May 1810) was a German racialist, philosopher, historian, and writer born in Warstade. He supported the polygenist theory of human origins. He was a member of the Göttingen School of History.

Biogra ...

, who first defined the Caucasian race, posited a "''binary racial scheme''" of two races with the Caucasian whose racial purity was exemplified by the "''venerated... ancient Germans''", although he considered some Europeans as impure "''dirty whites''"; and "''Mongolians''", who consisted of everyone else.Painter, Nell Irvin

Nell Irvin Painter (born Nell Elizabeth Irvin; August 2, 1942) is an American historian notable for her works on United States Southern history of the nineteenth century. She is retired from Princeton University as the Edwards Professor of Ameri ...

. Yale University. "Why White People are Called Caucasian?" 2003. September 27, 2007. ; Keevak, Michael. Becoming Yellow: A Short History of Racial Thinking. Princeton University Press, 2011. . Meiners did not include the Jew

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""T ...

s as Caucasians and ascribed them a "''permanently degenerate nature''".

Hannah Franzieka identified 19th-century writers who believed in the "Caucasian hypothesis" and noted that "Jean-Julien Virey and Louis Antoine Desmoulines were well-known supports of the idea that Europeans came from Mount Caucasus."Franzieka, Hannah. Berghahn Books: 2004. James Cowles Prichard's Anthropology: Remaking the Science of Man in Early In his political history of racial identity, Bruce Baum wrote,"Jean-Joseph Virey (1774-1847), a follower of Chistoph Meiners, claimed that "the human races... may divided... into those who are fair and white and those who are dark or black."Baum, Bruce David. The Rise and Fall of the Caucasian Race: A Political History of Racial Identity. New York University: 2006.

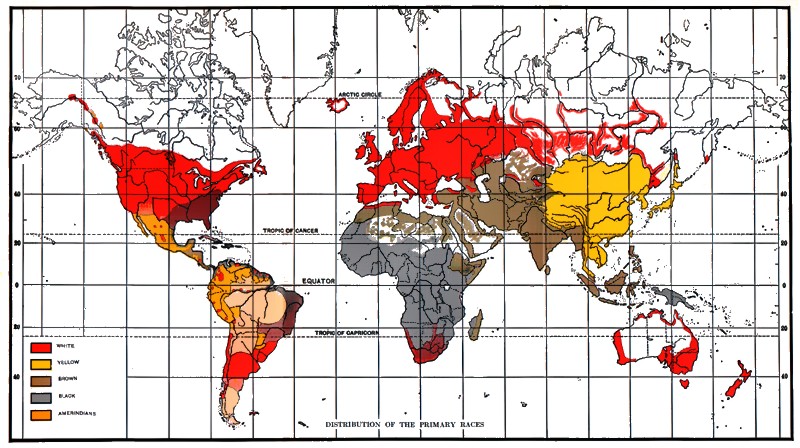

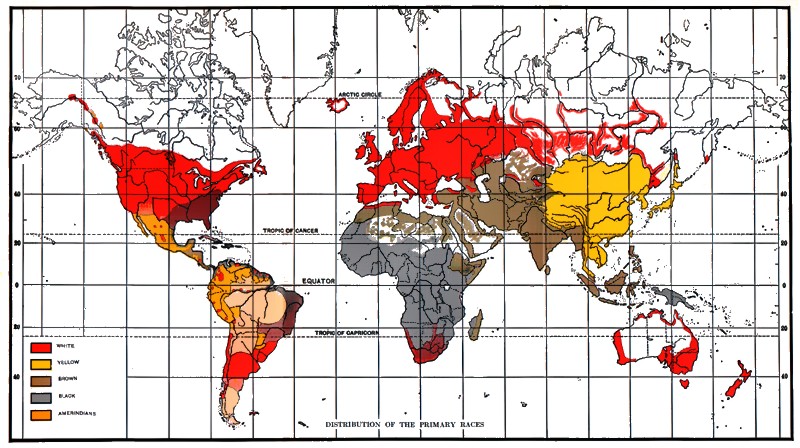

Lothrop Stoddard

Theodore Lothrop Stoddard (June 29, 1883 – May 1, 1950) was an American historian, journalist, political scientist, conspiracy theorist, white supremacist, and white nationalist. Stoddard wrote several books which advocated eugenics and sci ...

in ''The Rising Tide of Color Against White World-Supremacy

''The Rising Tide of Color: The Threat Against White World-Supremacy'' (1920), by Lothrop Stoddard, is a book about racialism and geopolitics, which describes the collapse of white supremacy and colonialism because of the population growth amon ...

'' (1920) considered five races: White, Black, Yellow, Brown, and Amerindian. In this explicitly white supremacist

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White s ...

exposition of racial categorization, the "white" category is much more limited than in Blumenbach's scheme, essentially restricted to Europeans

Europeans are the focus of European ethnology, the field of anthropology related to the various ethnic groups that reside in the states of Europe. Groups may be defined by common genetic ancestry, common language, or both. Pan and Pfeil (20 ...

, while the separate "brown" category is introduced for non-European Caucasoid

The Caucasian race (also Caucasoid or Europid, Europoid) is an obsolete racial classification of human beings based on a now-disproven theory of biological race. The ''Caucasian race'' was historically regarded as a biological taxon which, de ...

subgroups in North Africa, Western, Central and South Asia.

Racial categories after 1945

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, more and more biologists and anthropologists began to discontinue use of the term "race" due to its association with political ideologies of racism

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one race over another. It may also mean prejudice, discrimination, or antagoni ...

. Thus, ''The Race Question

The Race Question is the first of four UNESCO statements about issues of race. It was issued on 18 July 1950 following World War II and Nazi racism to clarify what was scientifically known about race, and as a moral condemnation of racism.< ...

'' statement by the UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international coope ...

, in the 1950s, proposed to substitute the term "ethnic groups" to the concept of "race".

Categories such as Europid

The Caucasian race (also Caucasoid or Europid, Europoid) is an obsolete racial classification of human beings based on a now-disproven theory of biological race. The ''Caucasian race'' was historically regarded as a biological taxon which, de ...

, Mongoloid

Mongoloid () is an obsolete racial grouping of various peoples indigenous to large parts of Asia, the Americas, and some regions in Europe and Oceania. The term is derived from a now-disproven theory of biological race. In the past, other terms ...

, Negroid

Negroid (less commonly called Congoid) is an obsolete racial grouping of various people indigenous to Africa south of the area which stretched from the southern Sahara desert in the west to the African Great Lakes in the southeast, but also to i ...

, Australoid

Australo-Melanesians (also known as Australasians or the Australomelanesoid, Australoid or Australioid race) is an outdated historical grouping of various people indigenous to Melanesia and Australia. Controversially, groups from Southeast Asia an ...

remain in use in fields such as forensic anthropology

Forensic anthropology is the application of the anatomical science of anthropology and its various subfields, including forensic archaeology and forensic taphonomy, in a legal setting. A forensic anthropologist can assist in the identification ...

.

Color terminology remains in use in some countries with multiracial

Mixed race people are people of more than one race or ethnicity. A variety of terms have been used both historically and presently for mixed race people in a variety of contexts, including ''multiethnic'', ''polyethnic'', occasionally ''bi-eth ...

populations for the purpose of their official census

A census is the procedure of systematically acquiring, recording and calculating information about the members of a given population. This term is used mostly in connection with national population and housing censuses; other common censuses inc ...

, as in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

, where the official categories are "Black", "White", "Asian", "Native American and Alaska Natives" and "Native Hawaiians and Other Pacific Islanders" and in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

( since 1991) with official categories "White", "Asian" and "Black". Conversely, it is uncommon in English speaking countries to use "Yellow" to refer to Asian people

Asian people (or Asians, sometimes referred to as Asiatic people)United States National Library of Medicine. Medical Subject Headings. 2004. November 17, 200Nlm.nih.gov: ''Asian Continental Ancestry Group'' is also used for categorical purpos ...

or "Red" to refer to Indigenous peoples of the Americas

The Indigenous peoples of the Americas are the inhabitants of the Americas before the arrival of the European settlers in the 15th century, and the ethnic groups who now identify themselves with those peoples.

Many Indigenous peoples of the A ...

. This is due to historic negative associations of the terms (ex. Yellow Peril

The Yellow Peril (also the Yellow Terror and the Yellow Specter) is a racial color metaphor that depicts the peoples of East and Southeast Asia as an existential danger to the Western world. As a psychocultural menace from the Eastern world ...

and Redskin

Redskin is a slang term for Native Americans in the United States and First Nations in Canada. The term ''redskin'' underwent pejoration through the 19th to early 20th centuries and in contemporary dictionaries of American English it is lab ...

). However, some Asians have tried to reclaim the word by proudly self-identifying as "Yellow". Similarly, some Native Americans have tried to reclaim the term "Red".

Much of the color-based classification relates to groups that were politically significant at different points in US history (e.g., part of a wave of immigrants), and these categories do not have an obvious label for people from other groups, such as people from the Middle East or Central Asia. However, many Middle Eastern and South Asian people in the Anglophone world self-identify as "Brown

Brown is a color. It can be considered a composite color, but it is mainly a darker shade of orange. In the CMYK color model used in printing or painting, brown is usually made by combining the colors orange and black. In the RGB color model ...

", considering their skin color central to their identity

Identity may refer to:

* Identity document

* Identity (philosophy)

* Identity (social science)

* Identity (mathematics)

Arts and entertainment Film and television

* ''Identity'' (1987 film), an Iranian film

* ''Identity'' (2003 film), an ...

.

Symbolism and uses of color terminology

The Martinique-born FrenchFrantz Fanon

Frantz Omar Fanon (, ; ; 20 July 1925 – 6 December 1961), also known as Ibrahim Frantz Fanon, was a French West Indian psychiatrist, and political philosopher from the French colony of Martinique (today a French department). His works have b ...

and African-American writers Langston Hughes

James Mercer Langston Hughes (February 1, 1901 – May 22, 1967) was an American poet, social activist, novelist, playwright, and columnist from Joplin, Missouri. One of the earliest innovators of the literary art form called jazz poetry, H ...

, Maya Angelou

Maya Angelou ( ; born Marguerite Annie Johnson; April 4, 1928 – May 28, 2014) was an American memoirist, popular poet, and civil rights activist. She published seven autobiographies, three books of essays, several books of poetry, and ...

, and Ralph Ellison

Ralph Waldo Ellison (March 1, 1913 – April 16, 1994) was an American writer, literary critic, and scholar best known for his novel ''Invisible Man'', which won the National Book Award in 1953. He also wrote '' Shadow and Act'' (1964), a collec ...

, among others, wrote that negative symbolisms surrounding the word "black" outnumber positive ones. They argued that the good vs. bad dualism associated with white and black unconsciously frame prejudiced colloquialisms. In the 1970s the term ''black'' replaced ''Negro'' in the United States.

Tone gradations

In some societies people can be sensitive to gradations of skin tone, which may be due tomiscegenation

Miscegenation ( ) is the interbreeding of people who are considered to be members of different races. The word, now usually considered pejorative, is derived from a combination of the Latin terms ''miscere'' ("to mix") and ''genus'' ("race") ...

or to albinism

Albinism is the congenital absence of melanin in an animal or plant resulting in white hair, feathers, scales and skin and pink or blue eyes. Individuals with the condition are referred to as albino.

Varied use and interpretation of the term ...

and which can affect power and prestige. In 1930s Harlem

Harlem is a neighborhood in Upper Manhattan, New York City. It is bounded roughly by the Hudson River on the west; the Harlem River and 155th Street on the north; Fifth Avenue on the east; and Central Park North on the south. The greater Ha ...

slang, such gradations were described by a tonescale of " high yaller (yellow), yaller, high brown, vaseline brown, seal brown, low brown, dark brown". These terms were sometimes referred to in blues music

Blues is a music genre and musical form which originated in the Deep South of the United States around the 1860s. Blues incorporated spirituals, work songs, field hollers, shouts, chants, and rhymed simple narrative ballads from the Afric ...

, both in the words of songs and in the names of performers. In 1920s Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

, Willie Perryman followed his older brother Rufus in becoming a blues piano player: both were albino Negroes with pale skin, reddish hair and poor eyesight. Rufus was already well established as "Speckled Red

Rufus George Perryman (October 23, 1892 – January 2, 1973), known as Speckled Red, was an American blues and boogie-woogie piano player and singer noted for his recordings of "The Dirty Dozens", exchanges of insults and vulgar remarks that have ...

", Willie became "Piano Red

Willie Lee Perryman (October 19, 1911 – July 25, 1985), usually known professionally as Piano Red and later in life as Dr. Feelgood, was an American blues musician, the first to hit the pop music charts. He was a self-taught pianist who played ...

". The piano player and guitarist Tampa Red

Hudson Whittaker (born Hudson Woodbridge; January 8, 1903March 19, 1981), known as Tampa Red, was a Chicago blues musician.

His distinctive single-string slide guitar style, songwriting and bottleneck technique influenced other Chicago blues gu ...

from the same state developed his career in Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = List of sovereign states, Count ...

at that time: his name may have come from his light skin tone, or possibly reddish hair.

More recently such categorization has been noted in the Caribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean ...

. It is reported that skin tones play an important role in defining how Barbadians

Barbadians or Bajans

(pronounced ) are people who are identified with the country of Barbados, by being citizens or their descendants in the Barbadian diaspora. The connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Barba ...

view one another, and they use terms such as "brown skin, light skin, fair skin, high brown, red, and mulatto". An assessment of racism in Trinidad

Trinidad is the larger and more populous of the two major islands of Trinidad and Tobago. The island lies off the northeastern coast of Venezuela and sits on the continental shelf of South America. It is often referred to as the southernmos ...

notes people often being described by their skin tone, with the gradations being "HIGH RED – part White, part Black but 'clearer' than Brown-skin: HIGH BROWN – More white than Black, light skinned: DOUGLA

Dougla people (plural ''Douglas'') are Caribbean people who are of mixed African and Indian descent. The word ''Dougla'' (also Dugla or Dogla) is used throughout the Dutch and English-speaking Caribbean.

Definition

The word ''Dougla'' origin ...

– part Indian and part Black: LIGHT SKINNED, or CLEAR SKINNED Some Black, but more White: TRINI WHITE – Perhaps not all White, behaves like others but skin White". In Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of Hispa ...

, albinism has been stigmatized, but the albino dancehall

Dancehall is a genre of Jamaican popular music that originated in the late 1970s. Initially, dancehall was a more sparse version of reggae than the roots style, which had dominated much of the 1970s.Barrow, Steve & Dalton, Peter (2004) "The R ...

singer Yellowman

Winston Foster , better known by the stage name Yellowman, is a Jamaican reggae and dancehall deejay, also known as King Yellowman. He first became popular in Jamaica in the 1980s, rising to prominence with a series of singles that established ...

took his stage name in protest against such prejudice and has helped to end this stereotype.

United States

Racial segregation

Racial segregation is the systematic separation of people into racial or other ethnic groups in daily life. Racial segregation can amount to the international crime of apartheid and a crime against humanity under the Statute of the Intern ...

in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

was based on a binary classification, white vs. non-white, in which "white" was held to imply "purity" so that anyone with even the slightest amount of non-white ancestry was excluded from white privileges, and there could be no category of racially mixed people. In 1896 this doctrine was upheld in the ''Plessy v. Ferguson

''Plessy v. Ferguson'', 163 U.S. 537 (1896), was a landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision in which the Court ruled that racial segregation laws did not violate the U.S. Constitution as long as the facilities for each race were equal in qualit ...

'' Supreme Court case. Traditionally the main distinction was between "white" and "black", but Japanese Americans

are Americans of Japanese people, Japanese ancestry. Japanese Americans were among the three largest Asian Americans, Asian American ethnic communities during the 20th century; but, according to the 2000 United States census, 2000 census, they ...

could be accepted on both sides of the divide. As further racial groups were categorized, "white" became narrowly construed, and everyone else was categorised as a "person of color

The term "person of color" ( : people of color or persons of color; abbreviated POC) is primarily used to describe any person who is not considered "white". In its current meaning, the term originated in, and is primarily associated with, the U ...

", suggesting that "white" people have no race, while racial subdivision of those "of color" was unimportant.

At college campus protests during the 1960s, a "Flag of the Races" was in use, with five stripes comprising red, black, brown, yellow, and white tones.

In the 2000 United States Census

The United States census of 2000, conducted by the Census Bureau, determined the resident population of the United States on April 1, 2000, to be 281,421,906, an increase of 13.2 percent over the 248,709,873 people enumerated during the 1990 c ...

, two of the five self-designated races are labeled by a color. In the 2000 US Census, "White" refers to "person having origins in any of the original peoples of Europe, the Middle East, or North Africa." In the 2000 US Census, "Black or African American" refers to a "person having origins in any of the Black racial groups of Africa."

The other three self-designated races are not labeled by color.US Census Bureau. Race. 2000. Accessed July 14, 2008This is due to historic negative associations of terms like "Yellow" (for East Asians) and "Red" (for Native Americans) with racism. However, some Asian Americans and Native Americans have tried to reclaim these color terms by self-identifying as "Yellow" and "Red", respectively. Though not an official color or racial designation in the United States census, "

Brown

Brown is a color. It can be considered a composite color, but it is mainly a darker shade of orange. In the CMYK color model used in printing or painting, brown is usually made by combining the colors orange and black. In the RGB color model ...

" has been used to describe certain peoples such as Arab Americans and Indian Americans. Many Middle Eastern Americans have criticized the United States Census for denying them a racial designation, as they are classified as "White" by the United States census. Furthermore, though ''Asian'' as a racial term in the United States groups together ethnically diverse Asian peoples such as the Chinese, Indians, Filipinos and Japanese, its common usage has been criticized for only referring to East Asians. This has led some South and Southeast Asian Americans to use the term "Brown Asian" to separate themselves from East Asian Americans.

See also

*Biological anthropology

Biological anthropology, also known as physical anthropology, is a scientific discipline concerned with the biological and behavioral aspects of human beings, their extinct hominin ancestors, and related non-human primates, particularly from an e ...

(also known as physical anthropology)

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Color Terminology For RaceRace

Race, RACE or "The Race" may refer to:

* Race (biology), an informal taxonomic classification within a species, generally within a sub-species

* Race (human categorization), classification of humans into groups based on physical traits, and/or s ...

Color terminology

Race

Race, RACE or "The Race" may refer to:

* Race (biology), an informal taxonomic classification within a species, generally within a sub-species

* Race (human categorization), classification of humans into groups based on physical traits, and/or s ...

Color terminology