Xylophonist on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The xylophone (; ) is a

The xylophone (; ) is a

The modern western xylophone has bars of

The modern western xylophone has bars of

The instrument has obscure ancient origins. Nettl proposed that it originated in southeast Asia and came to Africa c. AD 500 when a group of Malayo-Polynesian speaking peoples migrated to Africa, and compared East African xylophone orchestras and Javanese and Balinese gamelan orchestras. This was more recently challenged by ethnomusicologist and linguist Roger Blench who posits an independent origin in of the Xylophone in Africa, citing, among the evidence for local invention, distinct features of African xylophones and the greater variety of xylophone types and proto-xylophone-like instruments in Africa.

The instrument has obscure ancient origins. Nettl proposed that it originated in southeast Asia and came to Africa c. AD 500 when a group of Malayo-Polynesian speaking peoples migrated to Africa, and compared East African xylophone orchestras and Javanese and Balinese gamelan orchestras. This was more recently challenged by ethnomusicologist and linguist Roger Blench who posits an independent origin in of the Xylophone in Africa, citing, among the evidence for local invention, distinct features of African xylophones and the greater variety of xylophone types and proto-xylophone-like instruments in Africa.

The silimba is a xylophone developed by

The silimba is a xylophone developed by

The earliest mention of a xylophone in Europe was in

The earliest mention of a xylophone in Europe was in

Many music educators use xylophones as a classroom resource to assist children's musical development. One method noted for its use of xylophones is

Many music educators use xylophones as a classroom resource to assist children's musical development. One method noted for its use of xylophones is

The xylophone (; ) is a

The xylophone (; ) is a musical instrument

A musical instrument is a device created or adapted to make musical sounds. In principle, any object that produces sound can be considered a musical instrument—it is through purpose that the object becomes a musical instrument. A person who pl ...

in the percussion family that consists of wooden bars struck by mallet

A mallet is a tool used for imparting force on another object, often made of rubber or sometimes wood, that is smaller than a maul or beetle, and usually has a relatively large head. The term is descriptive of the overall size and propor ...

s. Like the glockenspiel

The glockenspiel ( or , : bells and : set) or bells is a percussion instrument consisting of pitched aluminum or steel bars arranged in a keyboard layout. This makes the glockenspiel a type of metallophone, similar to the vibraphone.

The gloc ...

(which uses metal bars), the xylophone essentially consists of a set of tuned wooden keys arranged in the fashion of the keyboard of a piano

The piano is a stringed keyboard instrument in which the strings are struck by wooden hammers that are coated with a softer material (modern hammers are covered with dense wool felt; some early pianos used leather). It is played using a keyboa ...

. Each bar is an idiophone

An idiophone is any musical instrument that creates sound primarily by the vibration of the instrument itself, without the use of air flow (as with aerophones), strings ( chordophones), membranes ( membranophones) or electricity ( electroph ...

tuned to a pitch of a musical scale

In music theory, a scale is any set of musical notes ordered by fundamental frequency or pitch. A scale ordered by increasing pitch is an ascending scale, and a scale ordered by decreasing pitch is a descending scale.

Often, especially in the ...

, whether pentatonic

A pentatonic scale is a musical scale (music), scale with five Musical note, notes per octave, in contrast to the heptatonic scale, which has seven notes per octave (such as the major scale and minor scale).

Pentatonic scales were developed ...

or heptatonic

A heptatonic scale is a musical scale that has seven pitches, or tones, per octave. Examples include the major scale or minor scale; e.g., in C major: C D E F G A B C—and in the relative minor, A minor, natural minor: A B C D E F G A; the m ...

in the case of many African and Asian instruments, diatonic

Diatonic and chromatic are terms in music theory that are most often used to characterize scales, and are also applied to musical instruments, intervals, chords, notes, musical styles, and kinds of harmony. They are very often used as a ...

in many western children's instruments, or chromatic

Diatonic and chromatic are terms in music theory that are most often used to characterize scales, and are also applied to musical instruments, intervals, chords, notes, musical styles, and kinds of harmony. They are very often used as a p ...

for orchestral use.

The term ''xylophone'' may be used generally, to include all such instruments such as the marimba

The marimba () is a musical instrument in the percussion family that consists of wooden bars that are struck by mallets. Below each bar is a resonator pipe that amplifies particular harmonics of its sound. Compared to the xylophone, the timbre ...

, balafon

The balafon is a gourd-resonated xylophone, a type of struck idiophone. It is closely associated with the neighbouring Mandé, Senoufo and Gur peoples of West Africa, particularly the Guinean branch of the Mandinka ethnic group, but is now f ...

and even the semantron. However, in the orchestra

An orchestra (; ) is a large instrumental ensemble typical of classical music, which combines instruments from different families.

There are typically four main sections of instruments:

* bowed string instruments, such as the violin, viola, c ...

, the term ''xylophone'' refers specifically to a chromatic instrument of somewhat higher pitch range and drier timbre

In music, timbre ( ), also known as tone color or tone quality (from psychoacoustics), is the perceived sound quality of a musical note, sound or tone. Timbre distinguishes different types of sound production, such as choir voices and musica ...

than the marimba

The marimba () is a musical instrument in the percussion family that consists of wooden bars that are struck by mallets. Below each bar is a resonator pipe that amplifies particular harmonics of its sound. Compared to the xylophone, the timbre ...

, and these two instruments should not be confused. A person who plays the xylophone is known as a ''xylophonist'' or simply a ''xylophone player''.

The term is also popularly used to refer to similar instruments of the lithophone

A lithophone is a musical instrument consisting of a rock or pieces of rock which are struck to produce musical notes. Notes may be sounded in combination (producing harmony) or in succession (melody). It is an idiophone comparable to instrumen ...

and metallophone

A metallophone is any musical instrument in which the sound-producing body is a piece of metal (other than a metal string), consisting of tuned metal bars, tubes, rods, bowls, or plates. Most frequently the metal body is struck to produce sound, ...

types. For example, the Pixiphone and many similar toys described by the makers as xylophones have bars of metal rather than of wood, and so are in organology

Organology (from Ancient Greek () 'instrument' and (), 'the study of') is the science of musical instruments and their classifications. It embraces study of instruments' history, instruments used in different cultures, technical aspects of how i ...

regarded as glockenspiel

The glockenspiel ( or , : bells and : set) or bells is a percussion instrument consisting of pitched aluminum or steel bars arranged in a keyboard layout. This makes the glockenspiel a type of metallophone, similar to the vibraphone.

The gloc ...

s rather than as xylophones.

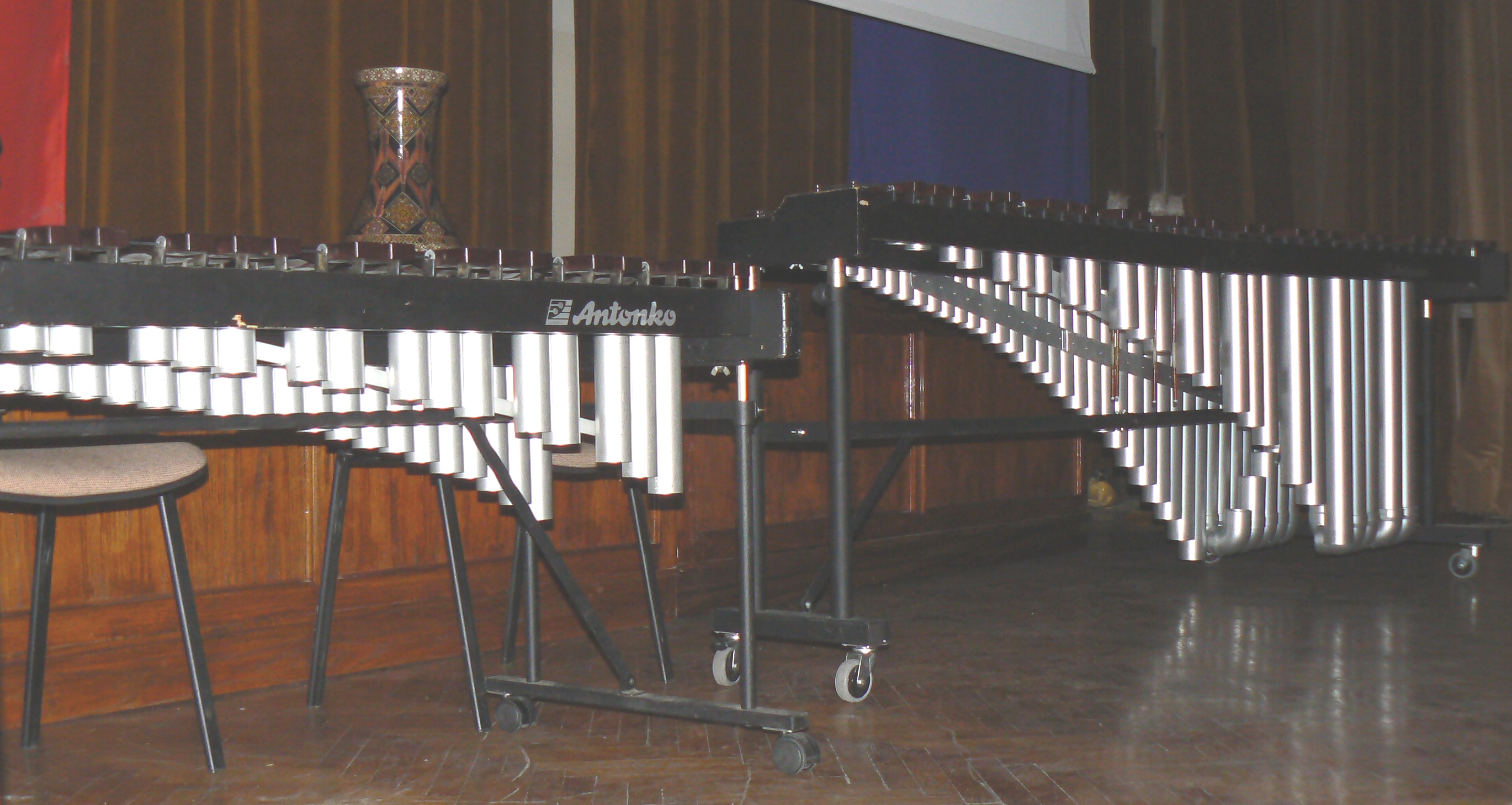

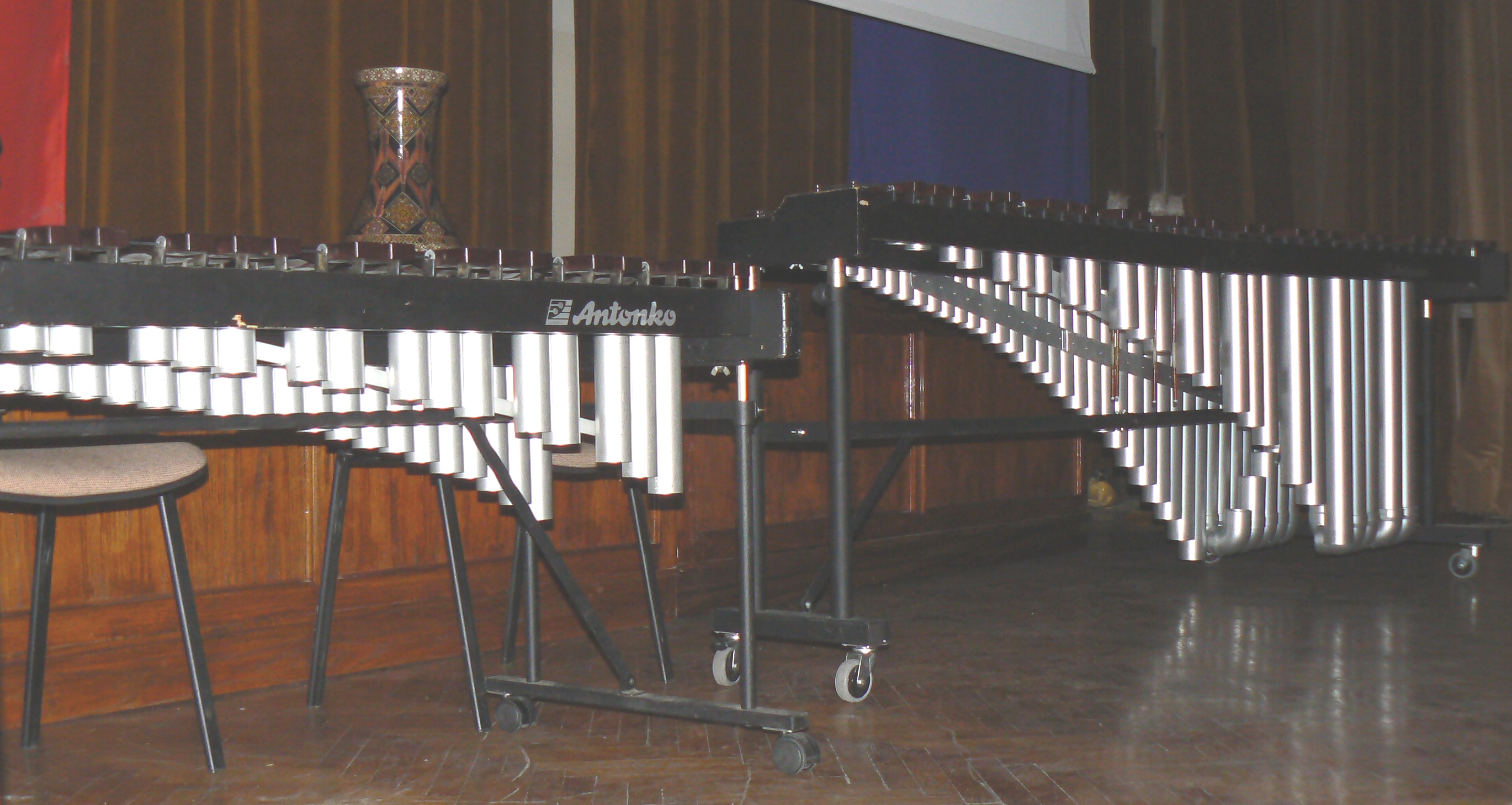

Construction of xylophones

The modern western xylophone has bars of

The modern western xylophone has bars of rosewood

Rosewood refers to any of a number of richly hued timbers, often brownish with darker veining, but found in many different hues.

True rosewoods

All genuine rosewoods belong to the genus ''Dalbergia''. The pre-eminent rosewood appreciated ...

, padauk, cocobolo

Cocobolo is a tropical hardwood of Central American trees belonging to the genus '' Dalbergia''. Only the heartwood of cocobolo is used; it is usually orange or reddish-brown, often with darker irregular traces weaving through the wood. The hear ...

, or various synthetic materials such as fiberglass

Fiberglass ( American English) or fibreglass (Commonwealth English) is a common type of fiber-reinforced plastic using glass fiber. The fibers may be randomly arranged, flattened into a sheet called a chopped strand mat, or woven into glass cl ...

or fiberglass-reinforced plastic which allows a louder sound. Some can be as small a range as octaves but concert xylophones are typically or 4 octaves. Like the glockenspiel, the xylophone is a transposing instrument

A transposing instrument is a musical instrument for which music notation is not written at concert pitch (concert pitch is the pitch on a non-transposing instrument such as the piano). For example, playing a written middle C on a transposing ...

: its parts are written one octave below the sounding notes.

Concert xylophones have tube resonators below the bars to enhance the tone and sustain. Frames are made of wood or cheap steel tubing: more expensive xylophones feature height adjustment and more stability in the stand. In other music cultures some versions have gourd

Gourds include the fruits of some flowering plant species in the family Cucurbitaceae, particularly ''Cucurbita'' and '' Lagenaria''. The term refers to a number of species and subspecies, many with hard shells, and some without. One of the ear ...

s that act as Helmholtz resonators. Others are "trough" xylophones with a single hollow body that acts as a resonator for all the bars. Old methods consisted of arranging the bars on tied bundles of straw, and, is still practiced today, placing the bars adjacent to each other in a ladder-like layout. Ancient mallets were made of willow wood with spoon-like bowls on the beaten ends.

Mallets

Xylophones should be played with very hard rubber, polyball, or acrylic mallets. Sometimes medium to hard rubber mallets, very hard core, or yarn mallets are used for softer effects. Lighter tones can be created on xylophones by using wooden-headed mallets made from rosewood, ebony, birch, or other hard woods.History

The instrument has obscure ancient origins. Nettl proposed that it originated in southeast Asia and came to Africa c. AD 500 when a group of Malayo-Polynesian speaking peoples migrated to Africa, and compared East African xylophone orchestras and Javanese and Balinese gamelan orchestras. This was more recently challenged by ethnomusicologist and linguist Roger Blench who posits an independent origin in of the Xylophone in Africa, citing, among the evidence for local invention, distinct features of African xylophones and the greater variety of xylophone types and proto-xylophone-like instruments in Africa.

The instrument has obscure ancient origins. Nettl proposed that it originated in southeast Asia and came to Africa c. AD 500 when a group of Malayo-Polynesian speaking peoples migrated to Africa, and compared East African xylophone orchestras and Javanese and Balinese gamelan orchestras. This was more recently challenged by ethnomusicologist and linguist Roger Blench who posits an independent origin in of the Xylophone in Africa, citing, among the evidence for local invention, distinct features of African xylophones and the greater variety of xylophone types and proto-xylophone-like instruments in Africa.

Asian xylophone

The earliest evidence of a true xylophone is from the 9th century insoutheast Asia

Southeast Asia, also spelled South East Asia and South-East Asia, and also known as Southeastern Asia, South-eastern Asia or SEA, is the geographical south-eastern region of Asia, consisting of the regions that are situated south of mainland ...

, while a similar hanging wood instrument, a type of harmonicon, is said by the Vienna Symphonic Library to have existed in 2000 BC in what is now part of China. The xylophone-like ranat was used in Hindu

Hindus (; ) are people who religiously adhere to Hinduism. Jeffery D. Long (2007), A Vision for Hinduism, IB Tauris, , pages 35–37 Historically, the term has also been used as a geographical, cultural, and later religious identifier for ...

regions (kashta tharang). In Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania between the Indian and Pacific oceans. It consists of over 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi, and parts of Borneo and New Gui ...

, few regions have their own type of xylophones. In North Sumatra

North Sumatra ( id, Sumatra Utara) is a province of Indonesia located on the northern part of the island of Sumatra. Its capital and largest city is Medan. North Sumatra is Indonesia's fourth most populous province after West Java, East Java and ...

, The Toba Batak people

Toba people (Surat Batak: ᯅᯖᯂ᯲ ᯖᯬᯅ) also referred to as Batak Toba people are the largest group of the Batak people of North Sumatra, Indonesia. The common phrase of ‘Batak’ usually refers to the Batak Toba people. This mist ...

use wooden xylophones known as the Garantung (spelled: "garattung"). Java

Java (; id, Jawa, ; jv, ꦗꦮ; su, ) is one of the Greater Sunda Islands in Indonesia. It is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the south and the Java Sea to the north. With a population of 151.6 million people, Java is the world's mo ...

and Bali

Bali () is a province of Indonesia and the westernmost of the Lesser Sunda Islands. East of Java and west of Lombok, the province includes the island of Bali and a few smaller neighbouring islands, notably Nusa Penida, Nusa Lembongan, and ...

use xylophones (called gambang

A gambang, properly called a gambang kayu ('wooden gambang') is a xylophone-like instrument used among people of Indonesia in gamelan and kulintang, with wooden bars as opposed to the metallic ones of the more typical metallophones in a gamelan ...

, Rindik and Tingklik) in gamelan

Gamelan () ( jv, ꦒꦩꦼꦭꦤ꧀, su, ᮌᮙᮨᮜᮔ᮪, ban, ᬕᬫᭂᬮᬦ᭄) is the traditional ensemble music of the Javanese, Sundanese, and Balinese peoples of Indonesia, made up predominantly of percussive instruments. T ...

ensembles. They still have traditional significance in Malaysia

Malaysia ( ; ) is a country in Southeast Asia. The federal constitutional monarchy consists of thirteen states and three federal territories, separated by the South China Sea into two regions: Peninsular Malaysia and Borneo's East Mal ...

, Melanesia

Melanesia (, ) is a subregion of Oceania in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It extends from Indonesia's New Guinea in the west to Fiji in the east, and includes the Arafura Sea.

The region includes the four independent countries of Fiji, V ...

, Indonesia, Thailand

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is b ...

, Myanmar

Myanmar, ; UK pronunciations: US pronunciations incl. . Note: Wikipedia's IPA conventions require indicating /r/ even in British English although only some British English speakers pronounce r at the end of syllables. As John Wells explai ...

, and regions of the Americas. In Myanmar, the xylophone is known as Pattala

The pattala ( my, ပတ္တလား ''patta.la:'', ; mnw, ဗာတ် ကလာ) is a Burmese xylophone, consisting of 24 bamboo slats called ''ywet'' () or ''asan'' () suspended over a boat-shaped resonating chamber. It is played with two ...

and is typically made of bamboo.

African xylophone

The term ''marimba'' is also applied to various traditional folk instruments such as the West Africa ''balafon

The balafon is a gourd-resonated xylophone, a type of struck idiophone. It is closely associated with the neighbouring Mandé, Senoufo and Gur peoples of West Africa, particularly the Guinean branch of the Mandinka ethnic group, but is now f ...

''. Early forms were constructed of bars atop a gourd

Gourds include the fruits of some flowering plant species in the family Cucurbitaceae, particularly ''Cucurbita'' and '' Lagenaria''. The term refers to a number of species and subspecies, many with hard shells, and some without. One of the ear ...

. The wood is first roasted around a fire before shaping the key to achieve the desired tone. The resonator is tuned to the key through careful choice of size of resonator, adjustment of the diameter of the mouth of the resonator using wasp wax and adjustment of the height of the key above the resonator. A skilled maker can produce startling amplification. The mallets used to play ''dibinda'' and ''mbila'' have heads made from natural rubber taken from a wild creeping plant. "Interlocking" or alternating rhythm features in Eastern African xylophone music such as that of the Makonde ''dimbila'', the Yao ''mangolongondo'' or the Shirima ''mangwilo'' in which the ''opachera'', the initial caller, is responded to by another player, the ''wakulela''. This usually doubles an already rapid rhythmic pulse that may also co-exist with a counter-rhythm.

Mbila

The mbila (plural "timbila") is associated with theChopi people

The Chopi are an ethnic group of Mozambique. They have lived primarily in the Zavala region of southern Mozambique, in the Inhambane Province. They traditionally lived a life of subsistence agriculture, traditionally living a rural existence, alt ...

of the Inhambane Province

Inhambane is a province of Mozambique located on the coast in the southern part of the country. It has an area of 68,615 km2 and a population of 1,488,676 (2017 census). The provincial capital is also called Inhambane.

The climate is tropi ...

, in southern Mozambique. It is not to be confused with the mbira

Mbira ( ) are a family of musical instruments, traditional to the Shona people of Zimbabwe. They consist of a wooden board (often fitted with a resonator) with attached staggered metal tines, played by holding the instrument in the hands and p ...

. The style

Style is a manner of doing or presenting things and may refer to:

* Architectural style, the features that make a building or structure historically identifiable

* Design, the process of creating something

* Fashion, a prevailing mode of clothing ...

of music played on it is believed to be the most sophisticated method of composition yet found among preliterate peoples. The gourd-resonated, equal-ratio heptatonic

A heptatonic scale is a musical scale that has seven pitches, or tones, per octave. Examples include the major scale or minor scale; e.g., in C major: C D E F G A B C—and in the relative minor, A minor, natural minor: A B C D E F G A; the m ...

-tuned mbila of Mozambique

Mozambique (), officially the Republic of Mozambique ( pt, Moçambique or , ; ny, Mozambiki; sw, Msumbiji; ts, Muzambhiki), is a country located in southeastern Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi ...

is typically played in large ensembles in a choreographed dance, perhaps depicting a historical drama. Ensembles consist of around ten xylophones of three or four sizes. A full orchestra would have two bass instruments called with three or four wooden keys played standing up using heavy mallets with solid rubber heads, three tenor , with ten keys and played seated, and the mbila itself, which has up to nineteen keys of which up to eight may be played simultaneously. The uses gourds and the and Masala apple shells as resonators. They accompany the dance with long compositions called or and consist of about 10 pieces of music grouped into 4 separate movements, with an overture, in different tempo

In musical terminology, tempo ( Italian, 'time'; plural ''tempos'', or ''tempi'' from the Italian plural) is the speed or pace of a given piece. In classical music, tempo is typically indicated with an instruction at the start of a piece (ofte ...

s and styles. The ensemble leader serves as poet, composer, conductor and performer

The performing arts are arts such as music, dance, and drama which are performed for an audience. They are different from the visual arts, which are the use of paint, canvas or various materials to create physical or static art objects. Perfor ...

, creating a text, improvising a melody

A melody (from Greek μελῳδία, ''melōidía'', "singing, chanting"), also tune, voice or line, is a linear succession of musical tones that the listener perceives as a single entity. In its most literal sense, a melody is a combina ...

partially based on the features of the Chopi tone language

Tone is the use of pitch in language to distinguish lexical or grammatical meaning – that is, to distinguish or to inflect words. All verbal languages use pitch to express emotional and other paralinguistic information and to convey emph ...

and composing a second contrapuntal

In music, counterpoint is the relationship between two or more musical lines (or voices) which are harmonically interdependent yet independent in rhythm and melodic contour. It has been most commonly identified in the European classical tradi ...

line. The musicians of the ensemble partially improvise

Improvisation is the activity of making or doing something not planned beforehand, using whatever can be found. Improvisation in the performing arts is a very spontaneous performance without specific or scripted preparation. The skills of impr ...

their parts. The composer then consults with the choreographer of the ceremony and adjustments are made. The longest and most important of these is the "Mzeno" which will include a song telling of an issue of local importance or even making fun of a prominent figure in the community! Performers include Eduardo Durão and Venancio Mbande.

Gyil

The ''gyil'' () is apentatonic

A pentatonic scale is a musical scale (music), scale with five Musical note, notes per octave, in contrast to the heptatonic scale, which has seven notes per octave (such as the major scale and minor scale).

Pentatonic scales were developed ...

instrument common to the Gur-speaking populations in Ghana

Ghana (; tw, Gaana, ee, Gana), officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It abuts the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, sharing borders with Ivory Coast in the west, Burkina Faso in the north, and Tog ...

, Burkina Faso

Burkina Faso (, ; , ff, 𞤄𞤵𞤪𞤳𞤭𞤲𞤢 𞤊𞤢𞤧𞤮, italic=no) is a landlocked country in West Africa with an area of , bordered by Mali to the northwest, Niger to the northeast, Benin to the southeast, Togo and Ghana t ...

, Mali

Mali (; ), officially the Republic of Mali,, , ff, 𞤈𞤫𞤲𞥆𞤣𞤢𞥄𞤲𞤣𞤭 𞤃𞤢𞥄𞤤𞤭, Renndaandi Maali, italics=no, ar, جمهورية مالي, Jumhūriyyāt Mālī is a landlocked country in West Africa. Ma ...

and Ivory Coast

Ivory Coast, also known as Côte d'Ivoire, officially the Republic of Côte d'Ivoire, is a country on the southern coast of West Africa. Its capital is Yamoussoukro, in the centre of the country, while its largest city and economic centre i ...

in West Africa

West Africa or Western Africa is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali ...

. The Gyil is the primary traditional instrument of the Dagara people of northern Ghana and Burkina Faso, and of the Lobi of Ghana, southern Burkina Faso, and Ivory Coast

Ivory Coast, also known as Côte d'Ivoire, officially the Republic of Côte d'Ivoire, is a country on the southern coast of West Africa. Its capital is Yamoussoukro, in the centre of the country, while its largest city and economic centre i ...

. The gyil is usually played in pairs, accompanied by a calabash gourd drum called a ''kuor''. It can also be played by one person with the drum and the stick part as accompaniment, or by a soloist. Gyil duets are the traditional music of Dagara funerals. The instrument is generally played by men, who learn to play while young, however, there is no restriction on gender.

The Gyil's design is similar to the ''Balaba'' or Balafon

The balafon is a gourd-resonated xylophone, a type of struck idiophone. It is closely associated with the neighbouring Mandé, Senoufo and Gur peoples of West Africa, particularly the Guinean branch of the Mandinka ethnic group, but is now f ...

used by the Mande-speaking Bambara, Dyula and Sosso

The Sosso Empire was a twelfth-century Kaniaga kingdom of West Africa.

The Kingdom of Sosso, also written as Soso or Susu, was an ancient kingdom on the coast of west Africa. During its empire, reigned their most famous leader, Sumaoro Kan ...

peoples further west in southern Mali

Mali (; ), officially the Republic of Mali,, , ff, 𞤈𞤫𞤲𞥆𞤣𞤢𞥄𞤲𞤣𞤭 𞤃𞤢𞥄𞤤𞤭, Renndaandi Maali, italics=no, ar, جمهورية مالي, Jumhūriyyāt Mālī is a landlocked country in West Africa. Ma ...

and western Burkina Faso

Burkina Faso (, ; , ff, 𞤄𞤵𞤪𞤳𞤭𞤲𞤢 𞤊𞤢𞤧𞤮, italic=no) is a landlocked country in West Africa with an area of , bordered by Mali to the northwest, Niger to the northeast, Benin to the southeast, Togo and Ghana t ...

, a region that shares many musical traditions with those of northern Ivory Coast and Ghana. It is made with 14 wooden keys of an African hardwood called liga attached to a wooden frame, below which hang calabash

Calabash (; ''Lagenaria siceraria''), also known as bottle gourd, white-flowered gourd, long melon, birdhouse gourd, New Guinea bean, Tasmania bean, and opo squash, is a vine grown for its fruit. It can be either harvested young to be consumed ...

gourds. Spider web silk covers small holes in the gourds to produce a buzzing sound and antelope sinew and leather are used for the fastenings. The instrument is played with rubber-headed wooden mallets.

Silimba

The silimba is a xylophone developed by

The silimba is a xylophone developed by Lozi people

Lozi people, or Barotse, are a southern African ethnic group who speak Lozi or Silozi, a Sotho–Tswana language. The Lozi people consist of more than 46 different ethnic groups and are primarily situated between Namibia, Angola, Botswana, Zimbab ...

in Barotseland

Barotseland ( Lozi: Mubuso Bulozi) is a region between Namibia, Angola, Botswana, Zimbabwe including half of eastern and northern provinces of Zambia and the whole of Democratic Republic of Congo's Katanga Province. It is the homeland of the ...

, western Zambia

Zambia (), officially the Republic of Zambia, is a landlocked country at the crossroads of Central, Southern and East Africa, although it is typically referred to as being in Southern Africa at its most central point. Its neighbours are t ...

. The tuned keys are tied atop resonating gourds

Gourds include the fruits of some flowering plant species in the family Cucurbitaceae, particularly ''Cucurbita'' and '' Lagenaria''. The term refers to a number of species and subspecies, many with hard shells, and some without. One of the earl ...

. The silimba, or shinjimba, is used by the Nkoya people

The Nkoya (also Shinkoya) people are a Bantu people native to Zambia, living mostly in the Western and Southern provinces and the Mankoya area.

As of 2006, they were estimated to number 146,000 people.

Besides Nkoya proper, Nkoya dialects includ ...

of Western Zambia

Zambia (), officially the Republic of Zambia, is a landlocked country at the crossroads of Central, Southern and East Africa, although it is typically referred to as being in Southern Africa at its most central point. Its neighbours are t ...

at traditional royal ceremonies like the Kazanga Nkoya. The silimba is an essential part of the folk music traditions of the Lozi people

Lozi people, or Barotse, are a southern African ethnic group who speak Lozi or Silozi, a Sotho–Tswana language. The Lozi people consist of more than 46 different ethnic groups and are primarily situated between Namibia, Angola, Botswana, Zimbab ...

and can be heard at their annual Kuomboka ceremony. The shilimba is now used in most parts of Zambia.

Akadinda, amadinda and mbaire

The akadinda and the amadinda are xylophone-like instruments originating inBuganda

Buganda is a Bantu kingdom within Uganda. The kingdom of the Baganda people, Buganda is the largest of the traditional kingdoms in present-day East Africa, consisting of Buganda's Central Region, including the Ugandan capital Kampala. The 14 mi ...

, in modern-day Uganda

}), is a landlocked country in East Africa. The country is bordered to the east by Kenya, to the north by South Sudan, to the west by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, to the south-west by Rwanda, and to the south by Tanzania. The ...

. The amadinda is made of twelve logs which are tuned in a pentatonic scale. It mainly is played by three players. Two players sit opposite of each other and play the same logs in an interlocking technique in a fast tempo. It has no gourd resonators or buzzing tone, two characteristics of many other African xylophones.

The amadinda was an important instrument at the royal court in Buganda

Buganda is a Bantu kingdom within Uganda. The kingdom of the Baganda people, Buganda is the largest of the traditional kingdoms in present-day East Africa, consisting of Buganda's Central Region, including the Ugandan capital Kampala. The 14 mi ...

, a Ugandan kingdom. A special type of notation is now used for this xylophone, consisting of numbers for and periods. as is also the case with the embaire, a type of xylophone originating in southern Uganda

}), is a landlocked country in East Africa. The country is bordered to the east by Kenya, to the north by South Sudan, to the west by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, to the south-west by Rwanda, and to the south by Tanzania. The ...

.

Balo

The ''balo'' (''balenjeh'', ''behlanjeh'') is used among theMandinka people

The Mandinka or Malinke are a West African ethnic group primarily found in southern Mali, the Gambia and eastern Guinea. Numbering about 11 million, they are the largest subgroup of the Mandé peoples and one of the largest ethnic-linguistic g ...

of West Africa. Its keys are mounted on gourds, and struck with mallets with rubber tips. The players typically wear iron cylinders and rings attached to their hands so that they jingle as they play.

Western xylophone

The earliest mention of a xylophone in Europe was in

The earliest mention of a xylophone in Europe was in Arnolt Schlick

Arnolt Schlick (July 18?,Keyl 1989, 110–11. c. 1455–1460 – after 1521) was a German organist, lutenist and composer of the Renaissance. He is grouped among the composers known as the Colorists. He was most probably born in Heidelberg and ...

's ''Spiegel der Orgelmacher und Organisten'' (1511), where it is called ''hültze glechter'' ("wooden clatter"). There follow other descriptions of the instrument, though the term "xylophone" is not used until the 1860s. The instrument was associated largely with the folk music of Central Europe, notably Poland and eastern Germany. An early version appeared in Slovakia

Slovakia (; sk, Slovensko ), officially the Slovak Republic ( sk, Slovenská republika, links=no ), is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the ...

and the earliest reference to a similar instrument came in the 14th century.

The first use of a European orchestral xylophone was in Camille Saint-Saëns

Charles-Camille Saint-Saëns (; 9 October 183516 December 1921) was a French composer, organist, conductor and pianist of the Romantic music, Romantic era. His best-known works include Introduction and Rondo Capriccioso (1863), the Piano C ...

' ''Danse Macabre

The ''Danse Macabre'' (; ) (from the French language), also called the Dance of Death, is an artistic genre of allegory of the Late Middle Ages on the universality of death.

The ''Danse Macabre'' consists of the dead, or a personification of ...

'', in 1874. By that time, the instrument had already been popularized to some extent by Michael Josef Gusikov, whose instrument was the five-row xylophone made of 28 crude wooden bars arranged in semitones in the form of a trapezoid and resting on straw supports. There were no resonators and it was played fast with spoon-shaped sticks. According to musicologist Curt Sachs

Curt Sachs (; 29 June 1881 – 5 February 1959) was a German musicologist. He was one of the founders of modern organology (the study of musical instruments). Among his contributions was the Hornbostel–Sachs system, which he created with Er ...

, Gusikov performed in garden concerts, variety shows, and as a novelty act at symphony concerts.

The western xylophone was used by early jazz bands and in vaudeville

Vaudeville (; ) is a theatrical genre of variety entertainment born in France at the end of the 19th century. A vaudeville was originally a comedy without psychological or moral intentions, based on a comical situation: a dramatic composition ...

. Its bright, lively sound worked well the syncopated dance music of the 1920s and 1930s. Red Norvo

Red Norvo (born Kenneth Norville; March 31, 1908 – April 6, 1999) was an American musician, one of jazz's early vibraphonists, known as "Mr. Swing". He helped establish the xylophone, marimba, and vibraphone as jazz instruments. His reco ...

, George Cary, George Hamilton Green

George Hamilton Green Jr. (May 23, 1893 – September 11, 1970) was a xylophonist, composer, and cartoonist born in Omaha, Nebraska. He was born into a musical family, both his grandfather and his father being composers, arrangers, and conductors ...

, Teddy Brown

Teddy is an English language given name, usually a hypocorism of Edward or Theodore. It may refer to:

People Nickname

* Teddy Atlas (born 1956), boxing trainer and fight commentator

* Teddy Bourne (born 1948), British Olympic epee fencer

* Tedd ...

and Harry Breuer were well-known users. As time passed, the xylophone was exceeded in popularity by the metal-key vibraphone

The vibraphone is a percussion instrument in the metallophone family. It consists of tuned metal bars and is typically played by using mallets to strike the bars. A person who plays the vibraphone is called a ''vibraphonist,'' ''vibraharpist ...

, which was developed in the 1920s. A xylophone with a range extending downwards into the marimba range is called a xylorimba.

In orchestral scores, a xylophone can be indicated by the French ''claquebois'', German ''Holzharmonika'' (literally "wooden harmonica"), or Italian ''silofono''. Shostakovich was particularly fond of the instrument; it has prominent roles in much of his work, including most of his symphonies

A symphony is an extended musical composition in Western classical music, most often for orchestra. Although the term has had many meanings from its origins in the ancient Greek era, by the late 18th century the word had taken on the meaning co ...

and his Cello Concerto No. 2. Modern xylophone players include Bob Becker, Evelyn Glennie

Dame Evelyn Elizabeth Ann Glennie, (born 19 July 1965) is a Scottish percussionist. She was selected as one of the two laureates for the Polar Music Prize of 2015.

Early life

Glennie was born in Methlick, Aberdeenshire in Scotland. The in ...

and Ian Finkel.

In the United States, there are Zimbabwean marimba bands in particularly high concentration in the Pacific Northwest, Colorado, and New Mexico, but bands exist from the East Coast through California and even to Hawaii and Alaska. The main event for this community is ZimFest, the annual Zimbabwean Music Festival. The bands are composed of instruments from high sopranos, through to lower soprano, tenor, baritone, and bass. Resonators are usually made with holes covered by thin cellophane (similar to the balafon

The balafon is a gourd-resonated xylophone, a type of struck idiophone. It is closely associated with the neighbouring Mandé, Senoufo and Gur peoples of West Africa, particularly the Guinean branch of the Mandinka ethnic group, but is now f ...

) to achieve the characteristic buzzing sound. The repertoires of U.S. bands tends to have a great overlap, due to the common source of the Zimbabwean musician Dumisani Maraire, who was the key person who first brought Zimbabwean music to the West, coming to the University of Washington in 1968.

Use in elementary education

Orff-Schulwerk

The Orff Schulwerk, or simply the Orff Approach, is a developmental approach used in music education. It combines music, movement, drama, and speech into lessons that are similar to a child's world of play. It was developed by the German com ...

, which combines the use of instruments, movement, singing and speech to develop children's musical abilities. Xylophones used in American general music classrooms are smaller, at about octaves, than the or more octave range of performance xylophones. The bass xylophone ranges are written from middle C to A an octave higher but sound one octave lower than written. The alto ranges are written from middle C to A an octave higher and sound as written. The soprano ranges are written from middle C to A an octave higher but sound one octave higher than written.

According to Andrew Tracey, marimbas were introduced to Zimbabwe in 1960. Zimbabwean

Zimbabwe (), officially the Republic of Zimbabwe, is a landlocked country located in Southeast Africa, between the Zambezi and Limpopo Rivers, bordered by South Africa to the south, Botswana to the south-west, Zambia to the north, and Moza ...

marimba based upon Shona music

Shona music is the music of the Shona people of Zimbabwe. There are several different types of traditional Shona music including mbira, singing, hosho and drumming. Very often, this music will be accompanied by dancing, and participation by t ...

has also become popular in the West, which adopted the original use of these instruments to play transcriptions of mbira

Mbira ( ) are a family of musical instruments, traditional to the Shona people of Zimbabwe. They consist of a wooden board (often fitted with a resonator) with attached staggered metal tines, played by holding the instrument in the hands and p ...

dzavadzimu (as well as ''nyunga nyunga'' and ''matepe'') music. The first of these transcriptions had originally been used for music education in Zimbabwe. Zimbabwean instruments are often in a diatonic C major scale, which allows them to be played with a 'western-tuned' mbira (G nyamaropa), sometimes with an added F key placed inline.

Famous solo works

* "Concertino for Xylophone" by Mayuzumi * "Scherzo For Xylophone and Piano" by Ptaczinska * "Robin Harry" by Inns * "Tambourin Chinoise" by KreislerFamous orchestral excerpts

* Barber, Samuel Medea's Meditation and Dance of Vengeance * Bartók, Béla The Wooden Prince * Bartók, Béla Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta * Britten, Benjamin The Young Person's Guide to the Orchestra * Copland, Aaron Hoe-Down from "Rodeo" * Gershwin, George Introduction from ''Porgy and Bess

''Porgy and Bess'' () is an English-language opera by American composer George Gershwin, with a libretto written by author DuBose Heyward and lyricist Ira Gershwin. It was adapted from Dorothy Heyward and DuBose Heyward's play '' Porgy'', ...

''

* Hindemith, Paul Kammermusik No. 1

* Holst, Gustav The Planets

* Janáček, Leoš Jenůfa

''Její pastorkyňa'' (''Her Stepdaughter''; commonly known as ''Jenůfa'' ) is an opera in three acts by Leoš Janáček to a Czech libretto by the composer, based on the play ''Její pastorkyňa'' by Gabriela Preissová. It was first performed ...

* Kabalevsky, Dimitri The Comedians, Suite

* Khachaturian, Aram "Sabre Dance

"Sabre Dance", ''Suserov par''; russian: Танец с саблями, ''Tanets s sablyami'' is a Movement (music), movement in the final act of Aram Khachaturian's ballet ''Gayane (ballet), Gayane'' (1942), where the Ballet dancer, dancers dis ...

" from ballet '' Gayane''

* Messiaen, Olivier Oiseaux exotiques

''Oiseaux exotiques'' (''Exotic birds'') is a piece for piano and small orchestra by Olivier Messiaen. It was written between 5 October 1953 and 3 January 1956 and was commissioned by Pierre Boulez. It is dedicated to Yvonne Loriod, the composer' ...

* Prokofiev, Sergei Scythian Suite

* Saint-Saëns, Camille Danse Macabre

The ''Danse Macabre'' (; ) (from the French language), also called the Dance of Death, is an artistic genre of allegory of the Late Middle Ages on the universality of death.

The ''Danse Macabre'' consists of the dead, or a personification of ...

* Saint-Saëns, Camille Fossils from Carnival of the Animals

''The Carnival of the Animals'' (''Le Carnaval des animaux'') is a humorous musical suite of fourteen movements, including " The Swan", by the French composer Camille Saint-Saëns. The work, about 25 minutes in duration, was written for privat ...

* Stravinsky, Igor The Firebird

''The Firebird'' (french: L'Oiseau de feu, link=no; russian: Жар-птица, Zhar-ptitsa, link=no) is a ballet and orchestral concert work by the Russian composer Igor Stravinsky. It was written for the 1910 Paris season of Sergei Diaghilev' ...

, Ballet (1910)

* Stravinsky, Igor Petrouchka

''Petrushka'' (french: link=no, Pétrouchka; russian: link=no, Петрушка) is a ballet and orchestral concert work by Russian composer Igor Stravinsky. It was written for the 1911 Paris season of Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes company; ...

(1911)

* Stravinsky, Igor Petrouchka (1947)

* Walton, William Belshazzar's Feast

See also

* Musical Stones of SkiddawCitations

Additional sources

* * * *External links

* * {{Authority control Keyboard percussion instruments Ghanaian musical instruments Stick percussion idiophones Orchestral percussion Mozambican music Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity Zambian musical instruments Ugandan musical instruments