Xi Zhongxun on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Xi Zhongxun (15 October 1913 – 24 May 2002) was a Chinese communist revolutionary and a subsequent political official in the

With the outbreak of full-scale

With the outbreak of full-scale  In July 1951, following the Communists' defeat of the Ma Clique armies in

In July 1951, following the Communists' defeat of the Ma Clique armies in

4 February 2013 When the Dalai Lama's brother visited Beijing in the early 1980s, Xi was still wearing that watch.

In September 1952, Xi Zhongxun became chief of the party's propaganda department and supervised cultural and education policies. At the

In September 1952, Xi Zhongxun became chief of the party's propaganda department and supervised cultural and education policies. At the

When he first arrived in Guangdong, he was told the provincial government had long been struggling to hold back the exodus of Chinese to Hong Kong since 1951. At the time, daily wages in Guangdong averaged 0.70 yuan, about 1/100 of wages in Hong Kong. Xi understood the disparity in standards of living and called for economic liberalisation in Guangdong. To do so, he needed to win over leaders in Beijing skeptical of the market economy. In meetings in April 1979, he convinced

When he first arrived in Guangdong, he was told the provincial government had long been struggling to hold back the exodus of Chinese to Hong Kong since 1951. At the time, daily wages in Guangdong averaged 0.70 yuan, about 1/100 of wages in Hong Kong. Xi understood the disparity in standards of living and called for economic liberalisation in Guangdong. To do so, he needed to win over leaders in Beijing skeptical of the market economy. In meetings in April 1979, he convinced

Biography of Xi Zhongxun

China Vitae

{{DEFAULTSORT:Xi, Zhongxun 1913 births 2002 deaths Chinese revolutionaries Chinese Communist Party politicians from Shaanxi Governors of Guangdong Heads of the Publicity Department of the Chinese Communist Party Members of the Secretariat of the Chinese Communist Party People's Republic of China politicians from Shaanxi Politicians from Weinan Xi Jinping family Members of the 12th Politburo of the Chinese Communist Party Vice Chairpersons of the National People's Congress Victims of the Cultural Revolution Burials at Babaoshan Revolutionary Cemetery

People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

. He is considered to be among the first and second generation of Chinese leadership. The contributions he made to the Chinese communist revolution and the development of the People's Republic, from the founding of Communist guerrilla bases in northwestern China in the 1930s to initiation of economic liberalization

Economic liberalization (or economic liberalisation) is the lessening of government regulations and restrictions in an economy in exchange for greater participation by private entities. In politics, the doctrine is associated with classical liber ...

in southern China in the 1980s, are numerous and broad. He was known for political moderation and for the setbacks he endured in his career. He was imprisoned and purged several times. His second son is the current General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party

The general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party () is the head of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), the sole ruling party of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Since 1989, the CCP general secretary has been the paramount lead ...

Xi Jinping

Xi Jinping ( ; ; ; born 15 June 1953) is a Chinese politician who has served as the general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and chairman of the Central Military Commission (CMC), and thus as the paramount leader of China, ...

.

Early life and education

Xi was born on 15 October 1913, to a land-owning family, in rural Fuping County,Shaanxi

Shaanxi (alternatively Shensi, see § Name) is a landlocked province of China. Officially part of Northwest China, it borders the province-level divisions of Shanxi (NE, E), Henan (E), Hubei (SE), Chongqing (S), Sichuan (SW), Gansu (W), N ...

. He joined the Chinese Communist Youth League in May 1926 and took part in student demonstrations in the spring of 1928, for which he was imprisoned by the ruling nationalist

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Th ...

authorities. In prison, he joined the Chinese Communist Party

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP), officially the Communist Party of China (CPC), is the founding and sole ruling party of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Under the leadership of Mao Zedong, the CCP emerged victorious in the Chinese Ci ...

(CCP) in 1928.

Career

Red Army

In 1930, Xi was appointed by the party to work in the Guominjun underYang Hucheng

Yang Hucheng () (26 November 1893 – 6 September 1949) was a Chinese general during the Warlord Era of Republican China and Kuomintang general during the Chinese Civil War.

Yang Hucheng joined the Xinhai Revolution in his youth and had be ...

. In March 1932, he led an unsuccessful uprising within that army in Liangdang, Gansu

Gansu (, ; alternately romanized as Kansu) is a province in Northwest China. Its capital and largest city is Lanzhou, in the southeast part of the province.

The seventh-largest administrative district by area at , Gansu lies between the Tibe ...

. Subsequently, he joined Communist guerrillas north of the Wei River. In March 1933, he joined Liu Zhidan

Liu Zhidan (4 October 1903 – 14 April 1936), also known as Liu Chih-tan, was a Chinese military commander and Communist leader, who founded the Shaanxi-Gansu-Ningxia Base Area in north-west China, which became the Yan'an Soviet.

Early life

Li ...

and others in founding the Shaanxi–Gansu (Shaangan) Border Region Soviet Area, and became the chairman of the Soviet area government while leading guerillas in resisting Nationalist incursions and expanding the Soviet area. In early 1935, the Shaanxi–Gansu Border and Northern Shaanxi Soviet Areas merged to form the Revolutionary Base Area

In Mao Zedong's original formulation of the military strategy of people's war, a revolutionary base area ( ''gémìng gēnjùdì''), or simply base area, is a local stronghold that the revolutionary force conducting the people's war should attem ...

of the Northwest and Xi became one of the leaders of the base area. But in September 1935, he along with Liu Zhidan and Gao Gang were jailed during a Leftist rectification campaign within the party. By his own account, he was within four days of being executed when CCP Chairman Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; also Romanization of Chinese, romanised traditionally as Mao Tse-tung. (26 December 1893 – 9 September 1976), also known as Chairman Mao, was a Chinese communist revolutionary who was the List of national founde ...

arrived on the scene and ordered Xi and his comrades released. Xi's guerrilla base in the Northwest gave refuge to Mao Zedong and the party center, and allowed them to end the Long March

The Long March (, lit. ''Long Expedition'') was a military retreat undertaken by the Red Army of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), the forerunner of the People's Liberation Army, to evade the pursuit of the National Army of the Chinese ...

. It is said that Xi's "Revolutionary Base Area of the Northwest saved the Party Center and the Party Center saved the revolutionaries of the Northwest." The base area eventually became the Yan'an Soviet, the headquarters of the Chinese Communist movement until 1947.

Sino-Japanese War

During theSecond Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) or War of Resistance (Chinese term) was a military conflict that was primarily waged between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. The war made up the Chinese theater of the wider Pacific T ...

, Xi stayed in the Yan'an Soviet to manage civilian and military affairs, boost economic production within the Soviet, and implement party policies. He was known for evaluating policies based on empirical assessment and resisting "leftist" extremism in implementing party directives. At the 7th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party in August 1945, he was named an alternate member of the Central Committee and became the deputy director of the party's organization department, in charge of making personnel decision. As World War II in China was winding down, he defeated Nationalist attack on the Yan'an Soviet at Futaishan and assisted the breakout of Wang Zhen's 359 Brigade from the North China Plain

The North China Plain or Huang-Huai-Hai Plain () is a large-scale downfaulted rift basin formed in the late Paleogene and Neogene and then modified by the deposits of the Yellow River. It is the largest alluvial plain of China. The plain is border ...

s.

Chinese Civil War and post-war transition

With the outbreak of full-scale

With the outbreak of full-scale civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

between Communists and Nationalists in early 1947, Xi remained in northwestern China to coordinate the protection and then recapture of the Yan'an Soviet Area. As political commissar, Xi and commander Zhang Zongxun

Zhang Zongxun (; 7 February 1908 – 14 September 1998) was a general of the People's Liberation Army of China.

Career

Zhang was born in Weinan, Shaanxi Province on 7 February 1908. He was enrolled in Whampoa Military Academy in 1926, and ...

defeated Nationalists west of Yan'an at the Battle of Xihuachi in March 1947. After Yan'an fell to Hu Zongnan

Hu Zongnan (; 16 May 1896 – 14 February 1962), courtesy name Shoushan (壽山), was a Chinese general in the National Revolutionary Army and then the Republic of China Army. Together with Chen Cheng and Tang Enbo, Hu, a native of Zh ...

on 19 March 1947, Xi worked on the staff of Peng Dehuai

Peng Dehuai (; October 24, 1898November 29, 1974) was a prominent Chinese Communist military leader, who served as China's Defense Minister from 1954 to 1959. Peng was born into a poor peasant family, and received several years of primary edu ...

in the battles to retake Yan'an and capture northwest China.

Xi directed the political work of the Northwest Political and Military Affairs Bureau, which was tasked with bringing Communist governance to the newly captured areas of the Northwest. In this capacity, Xi was known for his moderate policies and the use of non-military means to pacify rebellious areas.

In July 1951, following the Communists' defeat of the Ma Clique armies in

In July 1951, following the Communists' defeat of the Ma Clique armies in Qinghai

Qinghai (; alternately romanized as Tsinghai, Ch'inghai), also known as Kokonor, is a landlocked province in the northwest of the People's Republic of China. It is the fourth largest province of China by area and has the third smallest po ...

, remnants of the Muslim warlords incited rebellion among Tibetan tribesmen. 9 September 2011 Among those who took up arms was chieftain Xiang Qian of the Nganglha Tribe in eastern Qinghai

Qinghai (; alternately romanized as Tsinghai, Ch'inghai), also known as Kokonor, is a landlocked province in the northwest of the People's Republic of China. It is the fourth largest province of China by area and has the third smallest po ...

. As the PLA sent troops to quell the uprising, Xi Zhongxun urged for a political solution. Numerous envoys including Geshe Sherab Gyatso

Geshe Sherab Gyatso (; ) (1884–1968), was a Tibetan religious teacher and a politician who served in the Chinese government in the 1950s. After living in Lhasa for a period, he fell from favor with the establishment there in the 1930s and return ...

and the Panchen Lama

The Panchen Lama () is a tulku of the Gelug school of Tibetan Buddhism. Panchen Lama is one of the most important figures in the Gelug tradition, with its spiritual authority second only to Dalai Lama. Along with the council of high lamas, ...

went to negotiate. Though Xiang Qian rebuffed dozens of offers and the PLA managed to capture the chieftain's villages, Xi continued to pursue a political solution. He released captured tribesmen, offered generous terms to Xiang Qian and forgave those who took part in the uprising. In July 1952, Xiang Qian returned from hiding in the mountains, pledged his allegiance to the People's Republic and was invited by Xi to attend the graduation ceremony of the Nationalities College in Lanzhou. In 1953, Xiang Qiang became the chief of Jainca County

Jainca County, Chentsa County or Jainzha County (; ) is a county in Huangnan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture in Qinghai Province, China, to Tibetans in the area known as Malho Prefecture, part of Amdo. There are six townships, three towns and a to ...

. Mao compared Xi's deft treatment of Xiang Qian to Zhuge Liang

Zhuge Liang ( zh, t=諸葛亮 / 诸葛亮) (181 – September 234), courtesy name Kongming, was a Chinese statesman and military strategist. He was chancellor and later regent of the state of Shu Han during the Three Kingdoms period. He is ...

's conciliation

Conciliation is an alternative dispute resolution (ADR) process whereby the parties to a dispute use a conciliator, who meets with the parties both separately and together in an attempt to resolve their differences. They do this by lowering te ...

of Meng Huo in the ''Romance of the Three Kingdoms

''Romance of the Three Kingdoms'' () is a 14th-century historical novel attributed to Luo Guanzhong. It is set in the turbulent years towards the end of the Han dynasty and the Three Kingdoms period in Chinese history, starting in 184 AD ...

''.

Also in 1952, Xi Zhongxun halted the campaign of Wang Zhen and Deng Liqun to implement land reform and class struggle to pastoralist regions of Xinjiang

Xinjiang, SASM/GNC: ''Xinjang''; zh, c=, p=Xīnjiāng; formerly romanized as Sinkiang (, ), officially the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (XUAR), is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China (PRC), located in the northwes ...

. 7 July 2009 Xi, based on experience in Inner Mongolia, advised against assigning class labels and waging class struggle among pastoralists, but was ignored by Wang and Deng who directed the seizure of livestock from landowners and land from religious authorities. The policies inflamed social unrest in pastoralist northern Xinjiang where Ospan Batyr

Osman Islambayuly Batur ( kk, Оспан батыр, ''Ospan Batyr'', وسپان باتىر; zh, t=烏斯滿·巴圖爾; mn, t=Осман дээрэмчин, Осман дээрэмчин (Osman the Bandit); Mongolian: sometimes spelled as Ut ...

uprising had just been quelled. With the support of Mao, Xi reversed the policies, had Wang Zhen relieved from Xinjiang and released over a thousand herders from prison.

When the 14th Dalai Lama

The 14th Dalai Lama (spiritual name Jetsun Jamphel Ngawang Lobsang Yeshe Tenzin Gyatso, known as Tenzin Gyatso (Tibetan: བསྟན་འཛིན་རྒྱ་མཚོ་, Wylie: ''bsTan-'dzin rgya-mtsho''); né Lhamo Thondup), known as ...

visited Beijing in 1954 for several months of political meetings and studies in Chinese and Marxism, Xi spent time with the Tibetan leader, who fondly recalled Xi as "very friendly, comparatively open-minded, very nice." As a gift, the Dalai Lama gave Xi an Omega watch.Pramit Pal Chaudhuri, "Tibet's conquest of China's Xi Jinping family" ''Hindustan Times''4 February 2013 When the Dalai Lama's brother visited Beijing in the early 1980s, Xi was still wearing that watch.

High offices in Beijing, purge

In September 1952, Xi Zhongxun became chief of the party's propaganda department and supervised cultural and education policies. At the

In September 1952, Xi Zhongxun became chief of the party's propaganda department and supervised cultural and education policies. At the 8th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party

The 8th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party was held in two sessions, the first 15–27 September 1956 and the second 5–23 May 1958 in Beijing. It was the first Congress of the Chinese Communist Party since the start of it takin ...

in 1956, he was elected a member of the CCP Central Committee. In 1959, he became a vice-premier and worked under Premier Zhou Enlai

Zhou Enlai (; 5 March 1898 – 8 January 1976) was a Chinese statesman and military officer who served as the first premier of the People's Republic of China from 1 October 1949 until his death on 8 January 1976. Zhou served under Chairman M ...

in directing the State Council's lawmaking and policy research functions.

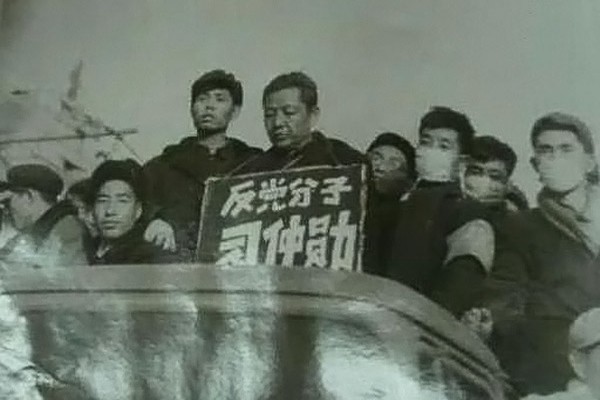

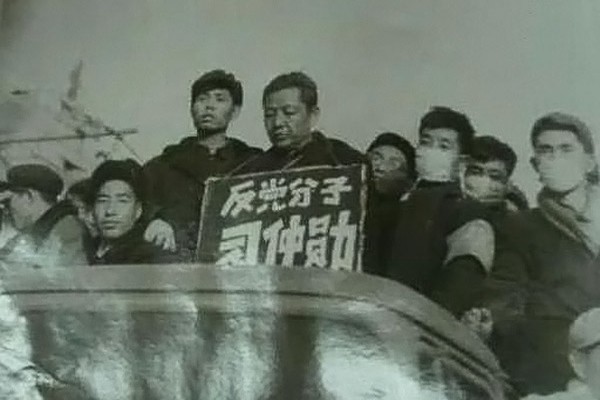

In 1962, he was accused by Kang Sheng of leading an anti-party clique for supporting the ''Biography of Liu Zhidan

Liu Zhidan (4 October 1903 – 14 April 1936), also known as Liu Chih-tan, was a Chinese military commander and Communist leader, who founded the Shaanxi-Gansu-Ningxia Base Area in north-west China, which became the Yan'an Soviet.

Early life

Li ...

'', and purged from all leadership positions. The biography, written by Li Jiantong () to commemorate Xi's former comrade who died a party martyr in 1936, was alleged to be a covert effort to subvert the party by rehabilitating Gao Gang, another former comrade who had been purged in 1954. Xi Zhongxun was forced to undergo self-criticism and in 1965 was demoted to the position of a deputy manager of a tractor factory in Luoyang

Luoyang is a city located in the confluence area of Luo River and Yellow River in the west of Henan province. Governed as a prefecture-level city, it borders the provincial capital of Zhengzhou to the east, Pingdingshan to the southeast, Nanyan ...

. Accessed 19 February 2012 During the Cultural Revolution

The Cultural Revolution, formally known as the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, was a sociopolitical movement in the People's Republic of China (PRC) launched by Mao Zedong in 1966, and lasting until his death in 1976. Its stated goa ...

, he was persecuted, jailed and spent long periods in confinement in Beijing. He regained his freedom in May 1975 and was assigned to another factory in Luoyang.

As Guangdong's top official

After the Cultural Revolution ended, Xi was fully rehabilitated at the Third Plenary Session of the 11th CCP Central Committee in December 1978. From 1978 to 1981, he held leadership roles inGuangdong Province

Guangdong (, ), alternatively romanized as Canton or Kwangtung, is a coastal province in South China on the north shore of the South China Sea. The capital of the province is Guangzhou. With a population of 126.01 million (as of 2020) ...

, successively as the second and then first provincial secretary, governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

and political commissar of the Guangdong Military Region. In Guangdong, he stabilized the provincial government and began to liberalize the economy.

Deng Xiaoping

Deng Xiaoping (22 August 1904 – 19 February 1997) was a Chinese revolutionary leader, military commander and statesman who served as the paramount leader of the China, People's Republic of China (PRC) from December 1978 to November 1989. Aft ...

to permit Guangdong to make its own foreign trade policy decisions and to invite foreign investment to projects in experimental areas along the provincial border with Hong Kong and Macau

Macau or Macao (; ; ; ), officially the Macao Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China (MSAR), is a city and special administrative region of China in the western Pearl River Delta by the South China Sea. With a pop ...

and in Shantou

Shantou, alternately romanized as Swatow and sometimes known as Santow, is a prefecture-level city on the eastern coast of Guangdong, China, with a total population of 5,502,031 as of the 2020 census (5,391,028 in 2010) and an administrative ...

, which has a large overseas diaspora. As for the name of the experimental areas, Deng said, "let's call them, 'special zones', fter all, yourShaanxi-Gansu Border Region began as a 'special zone'." Deng added, "The Central Government has no funds, but we can give you some favorable policies." Borrowing a phrase from their guerrilla war days, Deng told Xi, "You have to find a way, to fight a bloody path out." Xi submitted a formal proposal on the creation of special zones, later renamed special economic zones and in July 1979, the party center and State Council approved the creation of the first four special economic zones

A special economic zone (SEZ) is an area in which the business and trade laws are different from the rest of the country. SEZs are located within a country's national borders, and their aims include increasing trade balance, employment, increas ...

.

Retirement

In 1981, Xi returned to Beijing and was elected the deputy chair of theStanding Committee of the National People's Congress

The Standing Committee of the National People's Congress of the People's Republic of China (NPCSC) is the permanent body of the National People's Congress (NPC) of the People's Republic of China (PRC), which is the highest organ of state po ...

and also held the chair of the legal affairs committee. In this capacity, he oversaw the drafting of numerous laws. In September 1982, he was elected to the CCP Politburo and the CCP secretariat. In 1987, Deng Xiaoping and powerful elder Chen Yun

Chen Yun (, pronounced ; 13 June 1905 – 10 April 1995) was one of the most influential leaders of the People's Republic of China during the 1980s and 1990s and one of the major architects and important policy makers for the Reform and ...

were dissatisfied with the liberal inclination of Hu Yaobang

Hu Yaobang (; 20 November 1915 – 15 April 1989) was a high-ranking official of the People's Republic of China. He held the top office of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) from 1981 to 1987, first as Chairman from 1981 to 1982, then as Gen ...

, and called a meeting to force Hu to resign as CCP General Secretary. Xi was the only one that defended Hu. Xi retired from public service in April 1988 and spent most of his retirement years in Shenzhen

Shenzhen (; ; ; ), also historically known as Sham Chun, is a major sub-provincial city and one of the special economic zones of China. The city is located on the east bank of the Pearl River estuary on the central coast of southern provi ...

.

Personal life and death

In 1936, Xi married Hao Mingzhu, the niece of revolutionary fighter Wu Daifeng, in Shaanxi. The union lasted until 1944, and the couple had three children: one son, Xi Fuping (aka Xi Zhengning), and two daughters, Xi Heping, and Xi Ganping. According to official records, Xi Heping died during theCultural Revolution

The Cultural Revolution, formally known as the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, was a sociopolitical movement in the People's Republic of China (PRC) launched by Mao Zedong in 1966, and lasting until his death in 1976. Its stated goa ...

due to persecution, which historians have concluded means that she most likely committed suicide under duress. Little is known about Xi Ganping, except that she was retired by 2013 and regularly appears at meetings of red princelings. Xi Zhengning, meanwhile, was a researcher in the Ministry of Defence but later pursued a bureaucratic career; he died in 1998.

In 1944, Xi Zhongxun married Qi Xin

Qi Xin (; born November 3, 1926) is a Chinese author and member of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), who wrote various articles on her husband, Chinese communist revolutionary Xi Zhongxun. She is the mother of Xi Jinping, current General Sec ...

, his second wife, and had four children: Qi Qiaoqiao, Xi An'an, Xi Jinping

Xi Jinping ( ; ; ; born 15 June 1953) is a Chinese politician who has served as the general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and chairman of the Central Military Commission (CMC), and thus as the paramount leader of China, ...

and Xi Yuanping

Xi may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Xi'' (alternate reality game), a console-based game

* Xi, Japanese name for the video game ''Devil Dice''

Language

*Xi (letter), a Greek letter

* Xi, a Latin digraph used in British English to write ...

. Xi Jinping became the General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party

The general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party () is the head of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), the sole ruling party of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Since 1989, the CCP general secretary has been the paramount lead ...

and Chairman of the Central Military Commission from 15 November 2012, and has been President of China since March 2013.

Xi Zhongxun died 24 May 2002. His funeral and subsequent cremation at Babaoshan Revolutionary Cemetery on 30 May was attended by party and state leaders. His ashes were subsequently buried at a cemetery named in honor of him at Fuping County.

His official obituary described him as "an outstanding proletarian revolutionary," "a great communist soldier," and "one of the main founders and leaders of the revolutionary base areas in the Shaanxi-Gansu border region."

References

Citations

Sources

* * China's New Rulers: The Secret File, Andrew J. Nathan and Bruce Gilley, The New York Review Book * The Origins of the Cultural Revolution, Vol. 3 : The Coming of the Cataclysm, 1961-1966 (Columbia University Press, 1997)External links

Biography of Xi Zhongxun

China Vitae

{{DEFAULTSORT:Xi, Zhongxun 1913 births 2002 deaths Chinese revolutionaries Chinese Communist Party politicians from Shaanxi Governors of Guangdong Heads of the Publicity Department of the Chinese Communist Party Members of the Secretariat of the Chinese Communist Party People's Republic of China politicians from Shaanxi Politicians from Weinan Xi Jinping family Members of the 12th Politburo of the Chinese Communist Party Vice Chairpersons of the National People's Congress Victims of the Cultural Revolution Burials at Babaoshan Revolutionary Cemetery