Xanthian Obelisk on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Xanthian Obelisk, also known as the Xanthos or Xanthus Stele, the Xanthos or Xanthus Bilingual, the Inscribed Pillar of Xanthos or Xanthus, the Harpagus Stele, the Pillar of Kherei and the Columna Xanthiaca, is a

The Xanthian Obelisk, also known as the Xanthos or Xanthus Stele, the Xanthos or Xanthus Bilingual, the Inscribed Pillar of Xanthos or Xanthus, the Harpagus Stele, the Pillar of Kherei and the Columna Xanthiaca, is a

The stele lay in plain sight for centuries, though the upper portion was broken off and toppled by an earthquake at some time in antiquity. While charting the Lycian coast, Francis Beaufort, then a captain in the

The stele lay in plain sight for centuries, though the upper portion was broken off and toppled by an earthquake at some time in antiquity. While charting the Lycian coast, Francis Beaufort, then a captain in the  Progress along the coast was so slow that Fellows disembarked at Kas, obtained some horses, and proceeded to cross Ak Dağ, perhaps influenced by his interest in mountaineering. Climbing thousands of feet, Fellows observed tombs and ruins over the entire slopes of the mountains. The party cut short its mountain climbing, scrambling down to Patera, to avoid being blown off the slopes by heavy prevailing winds. From Patera they rode up the banks of the Xanthus and, on April 19, camped among the tombs of the ruined city.

Fellows took note of the obelisk architecture and the many inscriptions in excellent condition, but he did not linger to examine them further. After making a preliminary survey, he returned to Britain to publish his first journal, and to request the Board of Trustees of the

Progress along the coast was so slow that Fellows disembarked at Kas, obtained some horses, and proceeded to cross Ak Dağ, perhaps influenced by his interest in mountaineering. Climbing thousands of feet, Fellows observed tombs and ruins over the entire slopes of the mountains. The party cut short its mountain climbing, scrambling down to Patera, to avoid being blown off the slopes by heavy prevailing winds. From Patera they rode up the banks of the Xanthus and, on April 19, camped among the tombs of the ruined city.

Fellows took note of the obelisk architecture and the many inscriptions in excellent condition, but he did not linger to examine them further. After making a preliminary survey, he returned to Britain to publish his first journal, and to request the Board of Trustees of the

In October, 1841, Fellows received word that the firman had been granted. The preliminary work was over, and events began to move rapidly. HMS ''Beacon'', commanded by Captain Graves, had been reassigned to transport objects designated by Fellows, and Fellows was to board the ship in Malta. He wrote immediately to the British Museum offering to manage the expedition himself gratis, if he could receive free passage and rations on British naval vessels. The offer was accepted immediately and unconditionally. Once he boarded the ship unforeseen difficulties arose with the firman, and they found it necessary to voyage to Constantinople. There they received a firm commitment from the Sultan: "The Sublime Porte in interested in granting such demands, in consequence of the sincere friendship existing between the two governments." An additional problem was that the museum had allocated no funds for the expedition. Fellows offered to pay for it himself, to which no answer was received immediately.

At the mouth of the Xanthus, Captain Graves found no safe anchorage. Much to Fellows' chagrin, he was forced to anchor 50 miles away, but he left a flotilla of small boats under a lieutenant for the transport of the marbles. The flow of the Xanthus, according to Fellows, was greater than that of the Thames. The boats could make no headway in the strong currents, which Fellows estimated at 5 mph. Instead they pulled the boats upstream from the shore. The locals were exceedingly hospitable, supplying them with fresh edibles and pertinent advice, until they roasted a boar for dinner one night, after which they were despised for having eaten unclean meat. They reached Xanthus in December, 1841. Loading began in January.

On site they were limited as to what they could carry in small boats. The scene for the next few months was frenzied, with Fellows deciding ad hoc what was best to remove, rushing desperately to pry the objects from the earth, while the crews crated them. The largest objects were the

In October, 1841, Fellows received word that the firman had been granted. The preliminary work was over, and events began to move rapidly. HMS ''Beacon'', commanded by Captain Graves, had been reassigned to transport objects designated by Fellows, and Fellows was to board the ship in Malta. He wrote immediately to the British Museum offering to manage the expedition himself gratis, if he could receive free passage and rations on British naval vessels. The offer was accepted immediately and unconditionally. Once he boarded the ship unforeseen difficulties arose with the firman, and they found it necessary to voyage to Constantinople. There they received a firm commitment from the Sultan: "The Sublime Porte in interested in granting such demands, in consequence of the sincere friendship existing between the two governments." An additional problem was that the museum had allocated no funds for the expedition. Fellows offered to pay for it himself, to which no answer was received immediately.

At the mouth of the Xanthus, Captain Graves found no safe anchorage. Much to Fellows' chagrin, he was forced to anchor 50 miles away, but he left a flotilla of small boats under a lieutenant for the transport of the marbles. The flow of the Xanthus, according to Fellows, was greater than that of the Thames. The boats could make no headway in the strong currents, which Fellows estimated at 5 mph. Instead they pulled the boats upstream from the shore. The locals were exceedingly hospitable, supplying them with fresh edibles and pertinent advice, until they roasted a boar for dinner one night, after which they were despised for having eaten unclean meat. They reached Xanthus in December, 1841. Loading began in January.

On site they were limited as to what they could carry in small boats. The scene for the next few months was frenzied, with Fellows deciding ad hoc what was best to remove, rushing desperately to pry the objects from the earth, while the crews crated them. The largest objects were the

The stele is an important archaeological find pertaining to the

The stele is an important archaeological find pertaining to the

The Xanthian Obelisk, also known as the Xanthos or Xanthus Stele, the Xanthos or Xanthus Bilingual, the Inscribed Pillar of Xanthos or Xanthus, the Harpagus Stele, the Pillar of Kherei and the Columna Xanthiaca, is a

The Xanthian Obelisk, also known as the Xanthos or Xanthus Stele, the Xanthos or Xanthus Bilingual, the Inscribed Pillar of Xanthos or Xanthus, the Harpagus Stele, the Pillar of Kherei and the Columna Xanthiaca, is a stele

A stele ( ),Anglicized plural steles ( ); Greek plural stelai ( ), from Greek , ''stēlē''. The Greek plural is written , ''stēlai'', but this is only rarely encountered in English. or occasionally stela (plural ''stelas'' or ''stelæ''), whe ...

bearing an inscription currently believed to be trilingual, found on the acropolis

An acropolis was the settlement of an upper part of an ancient Greek city, especially a citadel, and frequently a hill with precipitous sides, mainly chosen for purposes of defense. The term is typically used to refer to the Acropolis of Athens, ...

of the ancient Lycian city of Xanthos

Xanthos ( Lycian: 𐊀𐊕𐊑𐊏𐊀 ''Arñna'', el, Ξάνθος, Latin: ''Xanthus'', Turkish: ''Ksantos'') was an ancient major city near present-day Kınık, Antalya Province, Turkey. The remains of Xanthos lie on a hill on the left b ...

, or Xanthus, near the modern town of Kınık in southern Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a list of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolia, Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with ...

. It was created when Lycia was part of the Persian Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire (; peo, 𐎧𐏁𐏂, , ), also called the First Persian Empire, was an ancient Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Based in Western Asia, it was the largest empire the world had ...

, and dates in all likelihood to ca. 400 BC. The pillar is seemingly a funerary marker of a dynastic satrap

A satrap () was a governor of the provinces of the ancient Median and Achaemenid Empires and in several of their successors, such as in the Sasanian Empire and the Hellenistic empires.

The satrap served as viceroy to the king, though with consid ...

of Achaemenid Lycia. The dynast in question is mentioned on the stele, but his name had been mostly defaced in the several places where he is mentioned: he could be Kherei

Kherei (circa 433-410 BC, or circa 410-390 BC) was dynast of Lycia, ruler of the area of Xanthos, at a time when this part of Anatolia was subject to the Persian, or Achaemenid, Empire.

Present-day knowledge of Lycia in the period of classica ...

(''Xerei'') or more probably his predecessor Kheriga

Kheriga (in Greek Gergis) was a Dynast of Lycia, who ruled circa 450-410 BCE. Kheriga is mentioned on the succession list of the Xanthian Obelisk, and is probably the owner of the sarcophagus that was standing on top of it.

Kheriga was son of ...

(''Xeriga'', Gergis in Greek).

The obelisk or pillar was originally topped by a tomb, most certainly belonging to Kheriga, in a way similar to the Harpy Tomb

The Harpy Tomb is a marble chamber from a pillar tomb that stands in the abandoned city of Xanthos, capital of ancient Lycia, a region of southwestern Anatolia in what is now Turkey. Built in the Persian Achaemenid Empire, and dating to approxi ...

. The top most likely fell down during an earthquake in ancient times. The tomb was decorated with reliefs of his exploits, and with a statue of the dynast standing on top.

The three languages are Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic peri ...

, Lycian and Milyan

Milyan, also known as Lycian B and previously Lycian 2, is an extinct ancient Anatolian language. It is attested from three inscriptions: two poems of 34 and 71 engraved lines, respectively, on the so-called Xanthian stele (or Xanthian O ...

(the last two are Anatolian languages

The Anatolian languages are an extinct branch of Indo-European languages that were spoken in Anatolia, part of present-day Turkey. The best known Anatolian language is Hittite, which is considered the earliest-attested Indo-European language.

...

and were previously known as Lycian A and Lycian B respectively). During its early period of study, the Lycian either could not be understood, or was interpreted as two dialects of one language, hence the term, bilingual. Another trilingual from Xanthus, the Letoon trilingual

The Letoon trilingual, or Xanthos trilingual, is an inscription in three languages: standard Lycian or Lycian A, Greek, and Aramaic covering the faces of a four-sided stone stele called the Letoon Trilingual Stele, discovered in 1973 during the ...

, was subsequently named from its three languages, Greek, Lycian A and Aramaic

The Aramaic languages, short Aramaic ( syc, ܐܪܡܝܐ, Arāmāyā; oar, 𐤀𐤓𐤌𐤉𐤀; arc, 𐡀𐡓𐡌𐡉𐡀; tmr, אֲרָמִית), are a language family containing many varieties (languages and dialects) that originated in ...

. They are both four-sided, both trilingual. The find sites are different. The key, unequivocal words are bilingual, Letoon

The Letoon ( grc, Λητῷον), sometimes Latinized as Letoum, was a sanctuary of Leto located 4km south of the ancient city of Xanthos to which it was closely associated, and along the Xanthos River. It was one of the most important religi ...

, Aramaic, Lycian B, Milyan. The equivocal words are stele, trilingual, Xanthus or Xanthos. "The Xanthus inscription" might refer to any inscription from Xanthus.

Discovery

First investigation of Xanthus

The stele lay in plain sight for centuries, though the upper portion was broken off and toppled by an earthquake at some time in antiquity. While charting the Lycian coast, Francis Beaufort, then a captain in the

The stele lay in plain sight for centuries, though the upper portion was broken off and toppled by an earthquake at some time in antiquity. While charting the Lycian coast, Francis Beaufort, then a captain in the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

, surveyed and reported on the ruins. Most of the ruins stood at elevated locations to which not even a mule trail remained. Reports of the white marble tombs, which were visible to travellers, attracted the interest of Victorian Age explorers, such as Charles Fellows

Sir Charles Fellows (31 August 1799 – 8 November 1860) was a British archaeologist and explorer, known for his numerous expeditions in what is present-day Turkey.

Biography

Charles Fellows was born at High Pavement, Nottingham on 31 August ...

.

On Saturday, April 14, 1838, Sir Charles Fellows, archaeologist, artist and mountaineer, member of the British Association

The British Science Association (BSA) is a charity and learned society founded in 1831 to aid in the promotion and development of science. Until 2009 it was known as the British Association for the Advancement of Science (BA). The current Chie ...

and man of independent means, arrived in an Arab dhow from Constantinople at the port of Tékrova, site of ancient Phaselis. On Friday he had arrived in Constantinople from England to seek permission to explore. According to him he was bent on an Anatolian "excursion" around Lycia. Although his journal is in the first person, it is clear from the text that others were present, and that he had some equipment with him. He was known also to the British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

and to the Royal Geographical Society

The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers), often shortened to RGS, is a learned society and professional body for geography based in the United Kingdom. Founded in 1830 for the advancement of geographical scien ...

, with whom he collaborated immediately on his return. The Ottoman Empire was on good terms with the British Empire, due to British support of the Ottomans during their defence against Napoleon. They granted permission and would cooperate in the subsequent removal of antiquities to the British Museum.

Progress along the coast was so slow that Fellows disembarked at Kas, obtained some horses, and proceeded to cross Ak Dağ, perhaps influenced by his interest in mountaineering. Climbing thousands of feet, Fellows observed tombs and ruins over the entire slopes of the mountains. The party cut short its mountain climbing, scrambling down to Patera, to avoid being blown off the slopes by heavy prevailing winds. From Patera they rode up the banks of the Xanthus and, on April 19, camped among the tombs of the ruined city.

Fellows took note of the obelisk architecture and the many inscriptions in excellent condition, but he did not linger to examine them further. After making a preliminary survey, he returned to Britain to publish his first journal, and to request the Board of Trustees of the

Progress along the coast was so slow that Fellows disembarked at Kas, obtained some horses, and proceeded to cross Ak Dağ, perhaps influenced by his interest in mountaineering. Climbing thousands of feet, Fellows observed tombs and ruins over the entire slopes of the mountains. The party cut short its mountain climbing, scrambling down to Patera, to avoid being blown off the slopes by heavy prevailing winds. From Patera they rode up the banks of the Xanthus and, on April 19, camped among the tombs of the ruined city.

Fellows took note of the obelisk architecture and the many inscriptions in excellent condition, but he did not linger to examine them further. After making a preliminary survey, he returned to Britain to publish his first journal, and to request the Board of Trustees of the British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

to ask Lord Palmerston

Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston, (20 October 1784 – 18 October 1865) was a British statesman who was twice Prime Minister of the United Kingdom in the mid-19th century. Palmerston dominated British foreign policy during the period ...

(Foreign Secretary) to request a firman

A firman ( fa, , translit=farmân; ), at the constitutional level, was a royal mandate or decree issued by a sovereign in an Islamic state. During various periods they were collected and applied as traditional bodies of law. The word firman com ...

from the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

for the removal of antiquities. He also sought the collaboration of Colonel William Martin Leake

William Martin Leake (14 January 17776 January 1860) was an English military man, topographer, diplomat, antiquarian, writer, and Fellow of the Royal Society. He served in the British military, spending much of his career in the

Mediterrane ...

, a noted antiquarian and traveller and, with others, including Beaufort, was a founding member of the Royal Geographical Society

The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers), often shortened to RGS, is a learned society and professional body for geography based in the United Kingdom. Founded in 1830 for the advancement of geographical scien ...

. While waiting for the firman, Fellows embarked for Lycia, arriving in Xanthus again in 1840.

Obelisk

On his return, armed with Beaufort's map, and Leake's directions, Fellows went in search for more Lycian cities, and found eleven more, accounting in all for 24 of Pliny's 36. He concentrated on coins and inscriptions. On April 17, he arrived again at Xanthus, writing: "Xanthus.— I am once more at my favourite city — ...." He noted that it was undespoiled; that is, the building stone had not been reused. He sawCyclopean

Cyclopean masonry is a type of stonework found in Mycenaean architecture, built with massive limestone boulders, roughly fitted together with minimal clearance between adjacent stones and with clay mortar or no use of mortar. The boulders typic ...

walls, gateways, paved roadways, trimmed stone blocks, and above all inscriptions, many in Greek, which he had no trouble reading and translating.

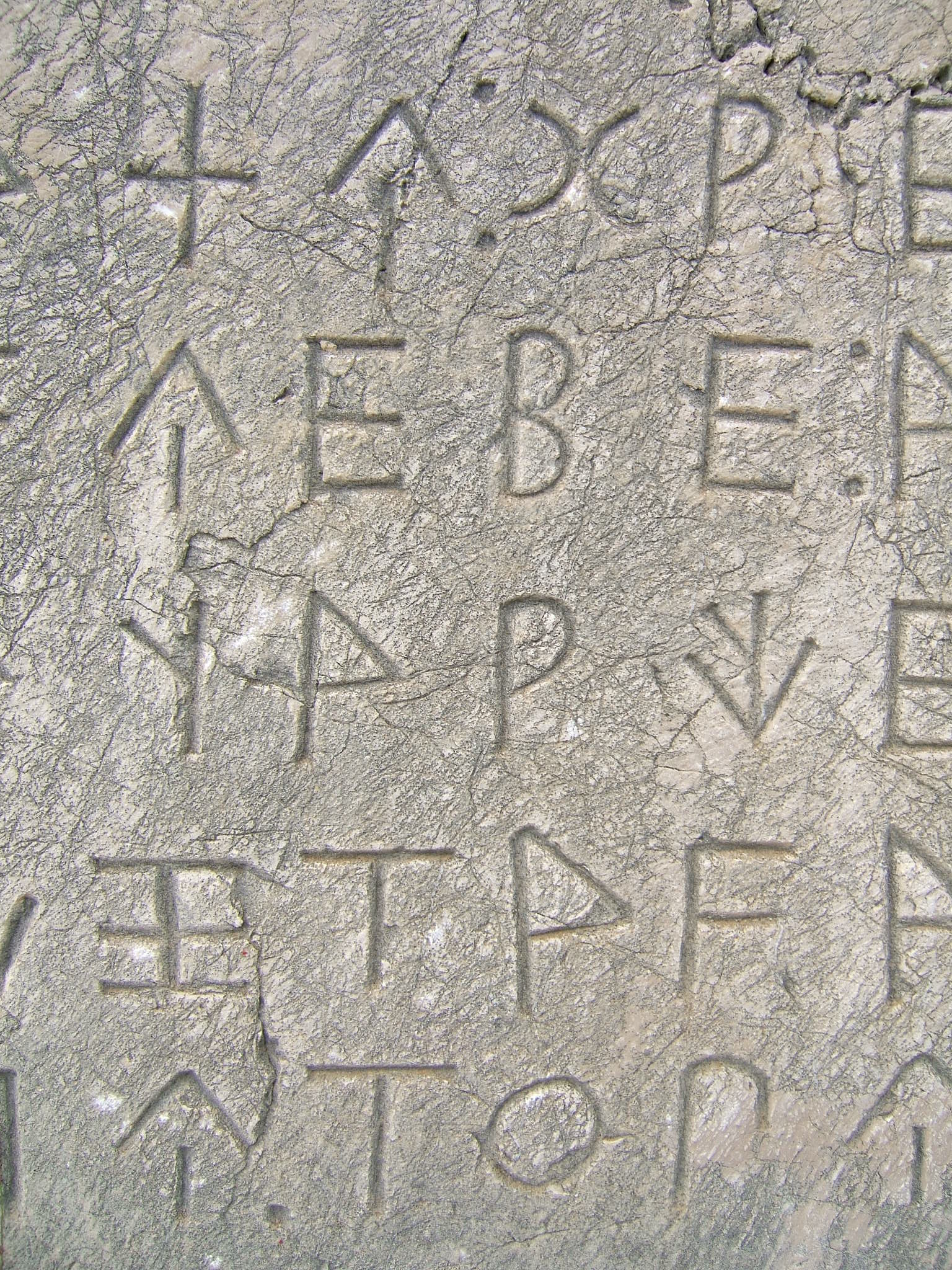

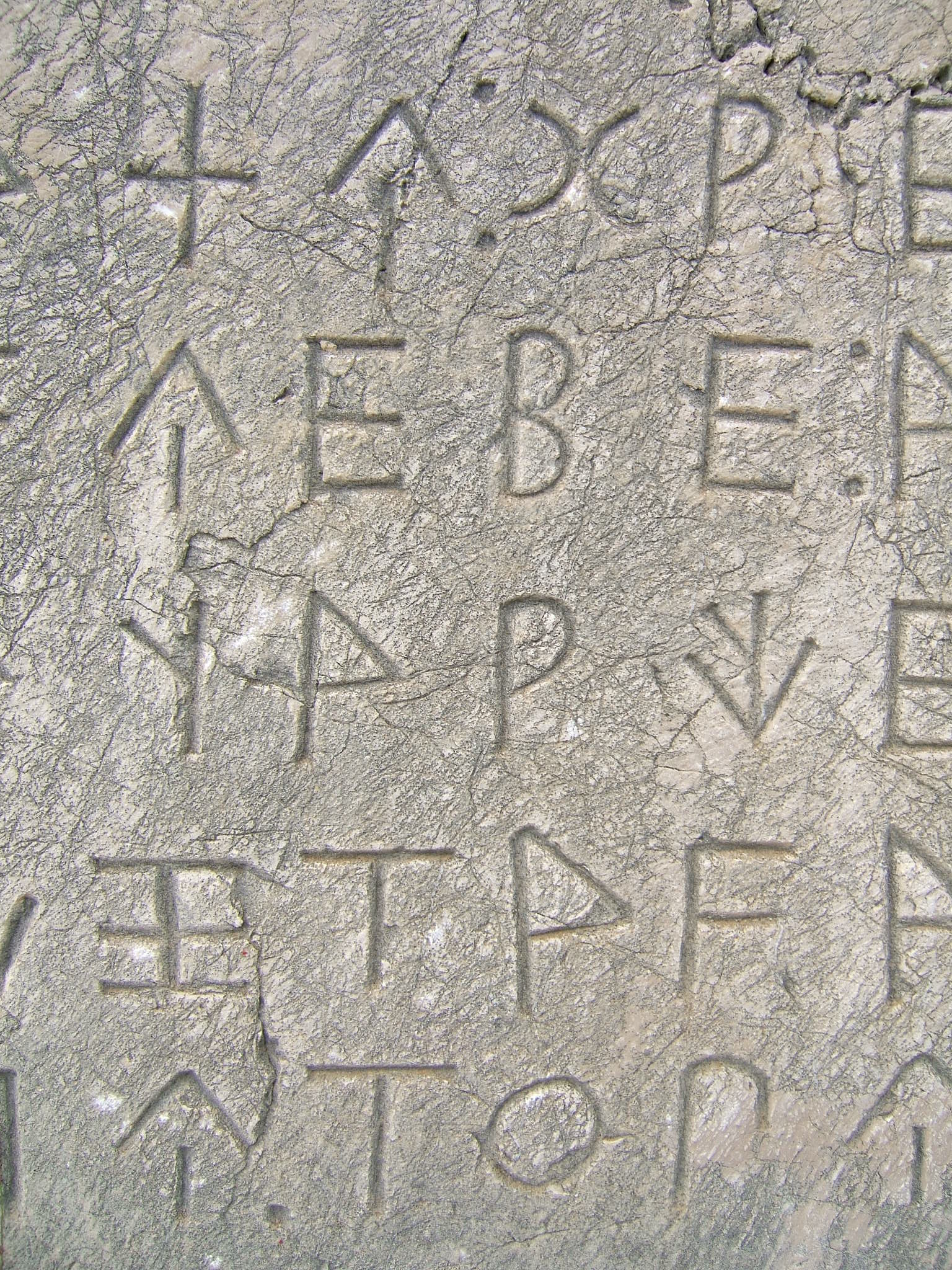

Fellows states that he had seen an obelisk on his previous trip, which, he said, he had mentioned in his first journal (if he did, it was not in the published version). Of the inscription, he said: "as the letters are beautifully cut, I have taken several impressions from them." His intent was to establish the forms of Lycian letters. He observed that "an earthquake has split off the upper part, which lies at the foot." As it weighed many tons, he could not move it. He excavated the obelisk from which it had been split, still standing, but embedded in the earth, and found that it stood on a pedestal. Of the lettering on it, he wrote: "The characters upon the northwest side, ... are cut in a finer and bolder style, and appear to be the most ancient." Seeing an inscription in Greek on the northeast side, he realised the importance of the find, but he did not say why, only that it was written in the first person, which "makes the monument itself speak."

Xanthian marbles

In October, 1841, Fellows received word that the firman had been granted. The preliminary work was over, and events began to move rapidly. HMS ''Beacon'', commanded by Captain Graves, had been reassigned to transport objects designated by Fellows, and Fellows was to board the ship in Malta. He wrote immediately to the British Museum offering to manage the expedition himself gratis, if he could receive free passage and rations on British naval vessels. The offer was accepted immediately and unconditionally. Once he boarded the ship unforeseen difficulties arose with the firman, and they found it necessary to voyage to Constantinople. There they received a firm commitment from the Sultan: "The Sublime Porte in interested in granting such demands, in consequence of the sincere friendship existing between the two governments." An additional problem was that the museum had allocated no funds for the expedition. Fellows offered to pay for it himself, to which no answer was received immediately.

At the mouth of the Xanthus, Captain Graves found no safe anchorage. Much to Fellows' chagrin, he was forced to anchor 50 miles away, but he left a flotilla of small boats under a lieutenant for the transport of the marbles. The flow of the Xanthus, according to Fellows, was greater than that of the Thames. The boats could make no headway in the strong currents, which Fellows estimated at 5 mph. Instead they pulled the boats upstream from the shore. The locals were exceedingly hospitable, supplying them with fresh edibles and pertinent advice, until they roasted a boar for dinner one night, after which they were despised for having eaten unclean meat. They reached Xanthus in December, 1841. Loading began in January.

On site they were limited as to what they could carry in small boats. The scene for the next few months was frenzied, with Fellows deciding ad hoc what was best to remove, rushing desperately to pry the objects from the earth, while the crews crated them. The largest objects were the

In October, 1841, Fellows received word that the firman had been granted. The preliminary work was over, and events began to move rapidly. HMS ''Beacon'', commanded by Captain Graves, had been reassigned to transport objects designated by Fellows, and Fellows was to board the ship in Malta. He wrote immediately to the British Museum offering to manage the expedition himself gratis, if he could receive free passage and rations on British naval vessels. The offer was accepted immediately and unconditionally. Once he boarded the ship unforeseen difficulties arose with the firman, and they found it necessary to voyage to Constantinople. There they received a firm commitment from the Sultan: "The Sublime Porte in interested in granting such demands, in consequence of the sincere friendship existing between the two governments." An additional problem was that the museum had allocated no funds for the expedition. Fellows offered to pay for it himself, to which no answer was received immediately.

At the mouth of the Xanthus, Captain Graves found no safe anchorage. Much to Fellows' chagrin, he was forced to anchor 50 miles away, but he left a flotilla of small boats under a lieutenant for the transport of the marbles. The flow of the Xanthus, according to Fellows, was greater than that of the Thames. The boats could make no headway in the strong currents, which Fellows estimated at 5 mph. Instead they pulled the boats upstream from the shore. The locals were exceedingly hospitable, supplying them with fresh edibles and pertinent advice, until they roasted a boar for dinner one night, after which they were despised for having eaten unclean meat. They reached Xanthus in December, 1841. Loading began in January.

On site they were limited as to what they could carry in small boats. The scene for the next few months was frenzied, with Fellows deciding ad hoc what was best to remove, rushing desperately to pry the objects from the earth, while the crews crated them. The largest objects were the Horse Tomb

The Tomb of Payava is a Lycian tall rectangular free-standing barrel-vaulted stone sarcophagus, and one of the most famous tombs of Xanthos. It was built in the Achaemenid Persian Empire, for Payava, who was probably the ruler of Xanthos, Lycia a ...

and parts of the Harpy Tomb

The Harpy Tomb is a marble chamber from a pillar tomb that stands in the abandoned city of Xanthos, capital of ancient Lycia, a region of southwestern Anatolia in what is now Turkey. Built in the Persian Achaemenid Empire, and dating to approxi ...

, which they had to disassemble, cutting them up with saws. The obelisks were unthinkable. Fellows contented himself with taking paper casts of the inscriptions, which, sent to the museum in advance, were the subject of Leake's first analysis and publication. In all they crated 80 tons of material in 82 cases, which they transported downriver in March, 1842, for loading onto the ship temporarily moored for the purpose.

In Malta Fellows received a few pleasant surprises. The museum was going to pay for the expedition. Fellows was invited to stay on at the museum. The marbles became known as the Xanthian marbles.

Inscriptions

The stele is an important archaeological find pertaining to the

The stele is an important archaeological find pertaining to the Lycian language

The Lycian language ( )Bryce (1986) page 30. was the language of the ancient Lycians who occupied the Anatolian region known during the Iron Age as Lycia. Most texts date back to the fifth and fourth century BC. Two languages are known as Lyci ...

. Similar to the Rosetta Stone

The Rosetta Stone is a stele composed of granodiorite inscribed with three versions of a Rosetta Stone decree, decree issued in Memphis, Egypt, in 196 BC during the Ptolemaic dynasty on behalf of King Ptolemy V Epiphanes. The top and middle te ...

, it has inscriptions both in Greek and in a previously mysterious language: Lycian, which, on further analysis, turned out to be two Luwian languages, Lycian and Milyan.

Referencing

Although not oriented on the cardinal directions, the stele presents four faces of continuous text that are traditionally described directionally, south, east, north and west, in that order, like the pages of a book. They are conventionally lettered a, b, c, and d. The whole book is inscription TAM I 44. The text of each page was inscribed in lines, conventionally numbered one through the number of the last line on the page. There are three pieces of text: * a.1 through c.19. A historical section of 250 lines in Lycian describing the major events in which the deceased was involved. * c.20 through c.31. A 12-line epigram in Greek in the style ofSimonides of Ceos

Simonides of Ceos (; grc-gre, Σιμωνίδης ὁ Κεῖος; c. 556–468 BC) was a Greek lyric poet, born in Ioulis on Ceos. The scholars of Hellenistic Alexandria included him in the canonical list of the nine lyric poets esteemed ...

honoring the deceased.

* c.32 through d.71. A paraphrase of the epigram in Milyan.

The pillar sits atop a tomb, and the inscription celebrates the deceased: a champion wrestler.

Language

In a section, ''Lycian Inscriptions'', of Appendix B of his second journal, Fellows includes his transliterations of TAM I 44, with remarks and attempted interpretations. He admits to being able to do little with it; however, he does note, "some curious analogies might be shown in the pronouns of the other Indo-Germanic languages". He had already decided, then, that the language was Indo-European. He had written this appendix from studies performed while he was waiting for the firman in 1840. The conclusions were not really his, however. He quotes a letter from his linguistic assistant, Daniel Sharpe, to whom he had sent copies, mentioningGrotefend

Georg Friedrich Grotefend (9 June 1775 – 15 December 1853) was a German epigraphist and philologist. He is known mostly for his contributions toward the decipherment of cuneiform.

Georg Friedrich Grotefend had a son, named Carl Ludwig Gro ...

's conclusion, based on five previously known inscriptions, that Lycian was Indo-Germanic.. By now he was referring to "the inscription on the obelisk at Xanthus." He had perceived that the deceased was mentioned as ''arppagooû tedēem'', "son of Harpagos," from which the stele also became known as "the Harpagos stele." Fellows identified this Harpagus with the conqueror of Lycia and dated the obelisk to 500 BC on the historical Harpagus

Harpagus, also known as Harpagos or Hypargus (Ancient Greek Ἅρπαγος; Akkadian: ''Arbaku''), was a Median general from the 6th century BC, credited by Herodotus as having put Cyrus the Great on the throne through his defection during the b ...

. His view has been called the Harpagid Theory by Antony Keen.

See also

*Xanthos

Xanthos ( Lycian: 𐊀𐊕𐊑𐊏𐊀 ''Arñna'', el, Ξάνθος, Latin: ''Xanthus'', Turkish: ''Ksantos'') was an ancient major city near present-day Kınık, Antalya Province, Turkey. The remains of Xanthos lie on a hill on the left b ...

* Anatolian languages

The Anatolian languages are an extinct branch of Indo-European languages that were spoken in Anatolia, part of present-day Turkey. The best known Anatolian language is Hittite, which is considered the earliest-attested Indo-European language.

...

* Lycian language

The Lycian language ( )Bryce (1986) page 30. was the language of the ancient Lycians who occupied the Anatolian region known during the Iron Age as Lycia. Most texts date back to the fifth and fourth century BC. Two languages are known as Lyci ...

Notes

References

* * * *Further reading

*External links

* {{Achaemenid Empire Ancient Near East steles Multilingual texts Lycian language Archaeological sites of classical Anatolia Archaeology of the Achaemenid Empire Achaemenid Anatolia