Wright flyer on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The ''Wright Flyer'' (also known as the ''Kitty Hawk'', ''Flyer'' I or the 1903 ''Flyer'') made the first sustained flight by a manned

In 1904, the Wrights continued refining their designs and piloting techniques in order to obtain fully controlled flight. Major progress toward this goal was achieved with a new machine called the

In 1904, the Wrights continued refining their designs and piloting techniques in order to obtain fully controlled flight. Major progress toward this goal was achieved with a new machine called the

The Flyer series of aircraft were the first to achieve controlled heavier-than-air flight, but some of the mechanical techniques the Wrights used to accomplish this were not influential for the development of aviation as a whole, although their theoretical achievements were. The ''Flyer'' design depended on wing-warping controlled by a hip cradle under the pilot, and a foreplane or "canard" for pitch control, features which would not scale and produced a hard-to-control aircraft. The Wrights' pioneering use of "roll control" by twisting the wings to change wingtip angle in relation to the airstream led to the more practical use of

The Flyer series of aircraft were the first to achieve controlled heavier-than-air flight, but some of the mechanical techniques the Wrights used to accomplish this were not influential for the development of aviation as a whole, although their theoretical achievements were. The ''Flyer'' design depended on wing-warping controlled by a hip cradle under the pilot, and a foreplane or "canard" for pitch control, features which would not scale and produced a hard-to-control aircraft. The Wrights' pioneering use of "roll control" by twisting the wings to change wingtip angle in relation to the airstream led to the more practical use of

File:Wright Flyer wind-tunnel-large NASA.jpg, The AIAA's ''Flyer'' reproduction undergoing testing in a

File:JAM Wright Flyer.png, ''Wright Flyer'' replica at Jeju Aerospace Museum

File:430-L1-S1 640.jpg, ''Wright Flyer'' wood and fabric taken to the Moon in 1969 by

Nasa.gov

Wrightflyer.org

Wrightexperience.com

''Air & Space Magazine''

1942 Smithsonian Annual Report acknowledging primacy of the ''Wright Flyer''

History of the ''Wright Flyer''

Wright State University Library {{Authority control 1903 in North Carolina Aircraft first flown in 1903 Articles containing video clips Canard aircraft History of Dayton, Ohio Individual aircraft in the collection of the Smithsonian Institution Prone pilot aircraft Single-engined twin-prop pusher aircraft 1900s United States experimental aircraft Flyer Aircraft with counter-rotating propellers

heavier-than-air

An aircraft is a vehicle that is able to fly by gaining support from the air. It counters the force of gravity by using either static lift or by using the dynamic lift of an airfoil, or in a few cases the downward thrust from jet engines. ...

powered and controlled aircraft—an airplane

An airplane or aeroplane (informally plane) is a fixed-wing aircraft that is propelled forward by thrust from a jet engine, propeller, or rocket engine. Airplanes come in a variety of sizes, shapes, and wing configurations. The broad ...

—on December 17, 1903. Invented and flown by Orville and Wilbur Wright, it marked the beginning of the pioneer era of aviation.

The Wright brothers flew the ''Wright Flyer'' four times that day on land now part of the town of Kill Devil Hills

Kill Devil Hills is a town in Dare County, North Carolina, United States. The population was 7,633 at the 2020 census, up from 6,683 in 2010. It is the most populous settlement in both Dare County and on the Outer Banks of North Carolina. The ...

, about south of Kitty Hawk, North Carolina

Kitty Hawk is a town in Dare County, North Carolina, United States, and is a part of what is known as North Carolina's Outer Banks. The population was 3,708 at the 2020 Census. It was established in the early 18th century as Chickahawk.

History ...

. The aircraft was preserved and is now exhibited in the National Air and Space Museum

The National Air and Space Museum of the Smithsonian Institution, also called the Air and Space Museum, is a museum in Washington, D.C., in the United States.

Established in 1946 as the National Air Museum, it opened its main building on the N ...

in Washington, D.C.

Design and construction

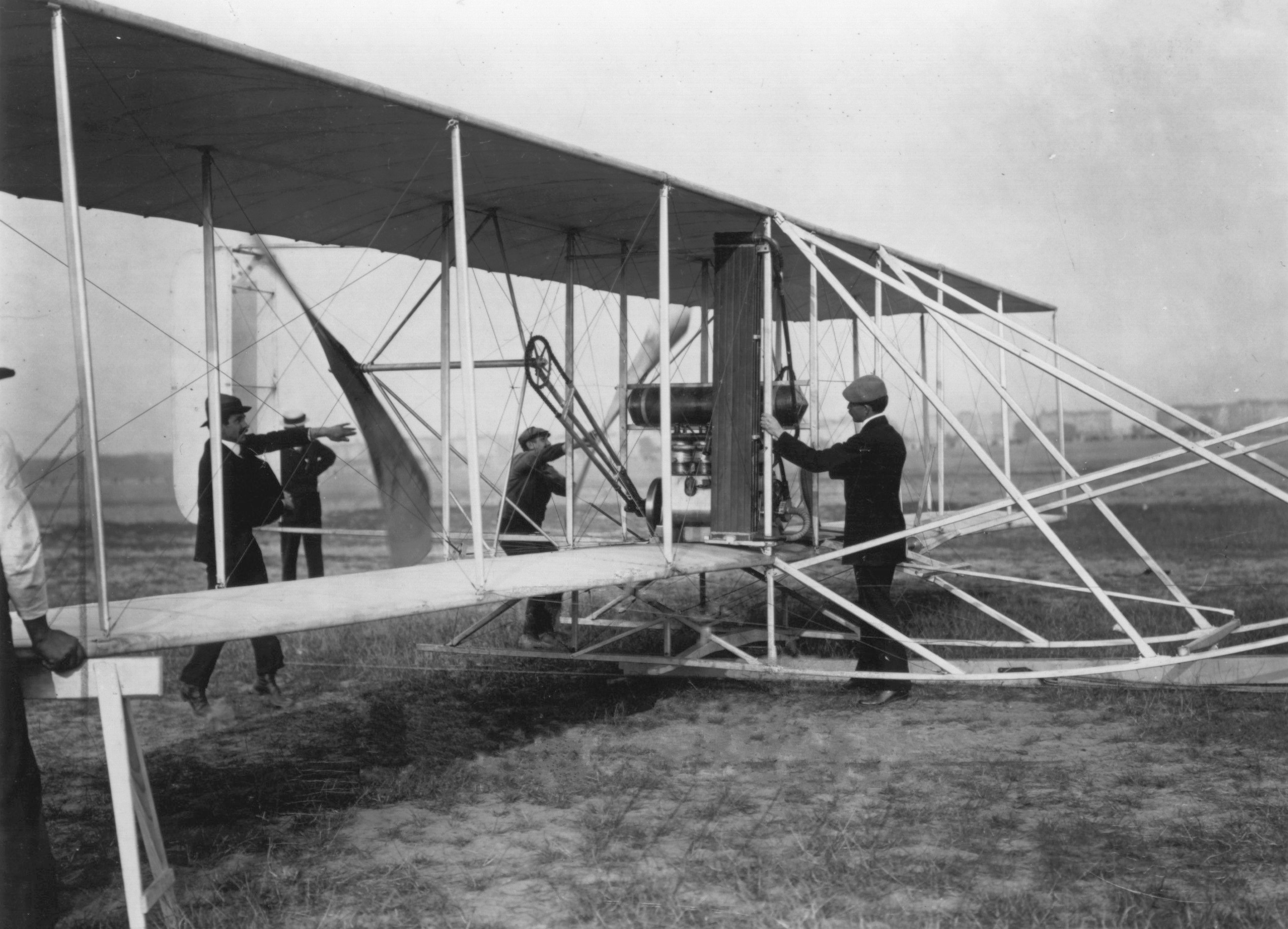

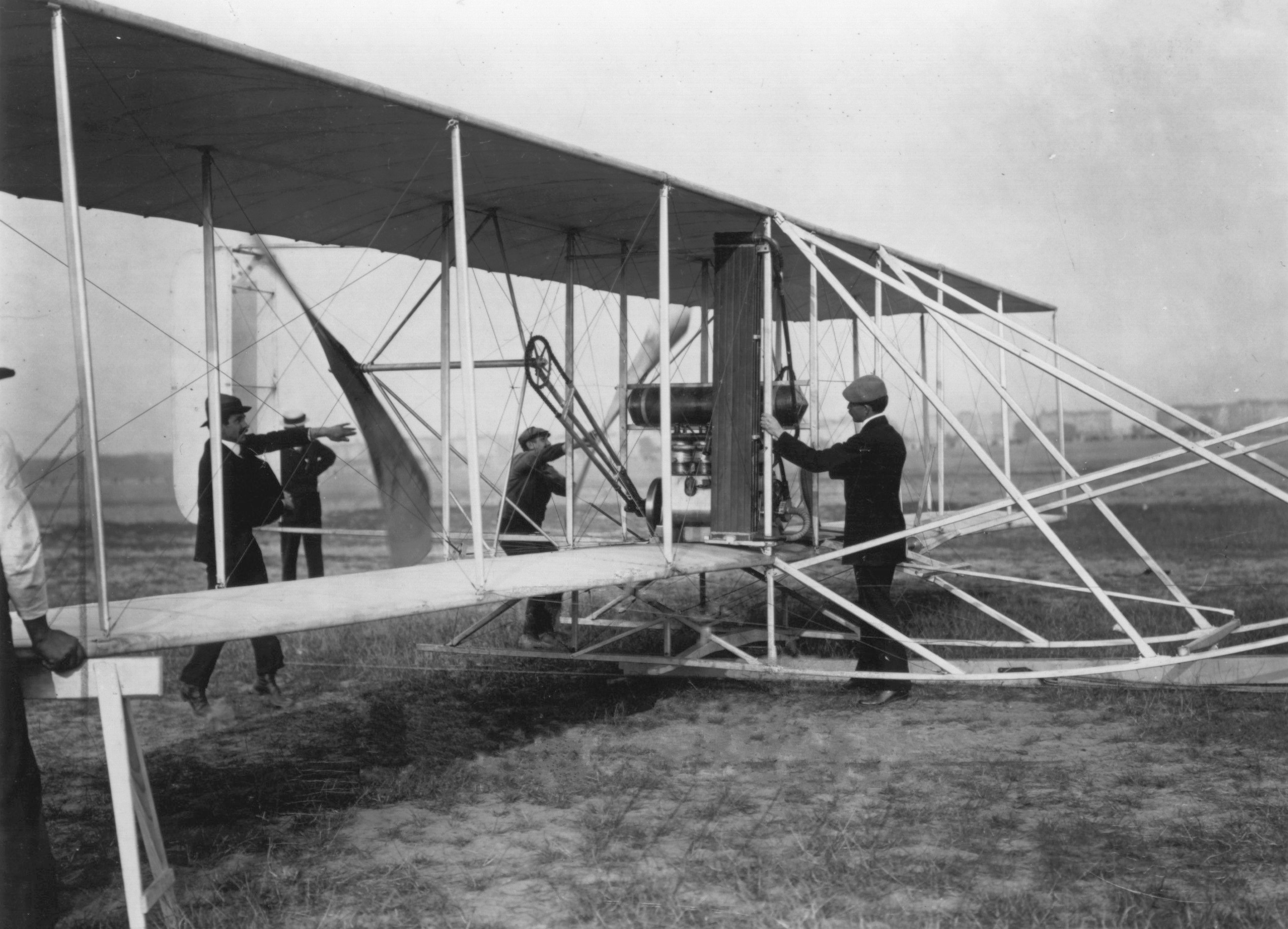

The ''Flyer'' was based on the Wrights' experience testing gliders at Kitty Hawk between 1900 and 1902. Their last glider, the1902 Glider

The Wright brothers designed, built and flew a series of three manned gliders in 1900–1902 as they worked towards achieving powered flight. They also made preliminary tests with a kite in 1899. In 1911 Orville conducted tests with a much mor ...

, led directly to the design of the ''Wright Flyer''.

The Wrights built the aircraft in 1903 using spruce

A spruce is a tree of the genus ''Picea'' (), a genus of about 35 species of coniferous evergreen trees in the family Pinaceae, found in the northern temperate and boreal (taiga) regions of the Earth. ''Picea'' is the sole genus in the subfam ...

for straight members of the airframe (such as wing spars) and ash wood for curved components (wing ribs). The wings were designed with a 1-in-20 camber. Since they could not find a suitable automobile engine for the task, they commissioned their employee Charlie Taylor to build a new design from scratch, a lightweight gasoline engine

A petrol engine (gasoline engine in American English) is an internal combustion engine designed to run on petrol (gasoline). Petrol engines can often be adapted to also run on fuels such as liquefied petroleum gas and ethanol blends (such as ''E ...

, weighing , with a fuel tank. A sprocket chain drive

Chain drive is a way of transmitting mechanical power from one place to another. It is often used to convey power to the wheels of a vehicle, particularly bicycles and motorcycles. It is also used in a wide variety of machines besides vehicles.

...

, borrowing from bicycle

A bicycle, also called a pedal cycle, bike or cycle, is a human-powered or motor-powered assisted, pedal-driven, single-track vehicle, having two wheels attached to a frame, one behind the other. A is called a cyclist, or bicyclist.

B ...

technology, powered the twin propellers

A propeller (colloquially often called a screw if on a ship or an airscrew if on an aircraft) is a device with a rotating hub and radiating blades that are set at a pitch to form a helical spiral which, when rotated, exerts linear thrust upon ...

, which were also made by hand. In order to avoid the risk of torque

In physics and mechanics, torque is the rotational equivalent of linear force. It is also referred to as the moment of force (also abbreviated to moment). It represents the capability of a force to produce change in the rotational motion of th ...

effects from affecting the aircraft handling, one drive chain was crossed over so that the propellers rotated in opposite directions.

According to Taylor:

The long propellers were based on airfoil number 9 from their wind tunnel data, which provided the best "gliding angle" for different angles of attack

In fluid dynamics, angle of attack (AOA, α, or \alpha) is the angle between a reference line on a body (often the chord line of an airfoil) and the vector representing the relative motion between the body and the fluid through which it is ...

. The propellers were connected to the engine by chains from the Indianapolis Chain Company, with a sprocket

A sprocket, sprocket-wheel or chainwheel is a profiled wheel with teeth that mesh with a chain, track or other perforated or indented material. The name 'sprocket' applies generally to any wheel upon which radial projections engage a chain pas ...

gear reduction of 23-to-8. Wilbur had calculated that slower turning blades generated greater thrust, and two of them were better than a single blade turning faster. Made from three lamination

Lamination is the technique/process of manufacturing a material in multiple layers, so that the composite material achieves improved strength, stability, sound insulation, appearance, or other properties from the use of the differing materia ...

s of spruce

A spruce is a tree of the genus ''Picea'' (), a genus of about 35 species of coniferous evergreen trees in the family Pinaceae, found in the northern temperate and boreal (taiga) regions of the Earth. ''Picea'' is the sole genus in the subfam ...

, the tips were covered with duck canvas, and the entire propeller painted with aluminum paint.

On November 5, 1903, the brothers tested their engine on the ''Wright Flyer'' at Kitty Hawk, but before they could tune the engine, the propeller hubs came loose. The drive shafts were sent back to Dayton for repair, and returned on 20 November. A hairline crack was discovered in one of the propeller shafts. Orville returned to Dayton on 30 November to make new spring steel

Spring steel is a name given to a wide range of steels used in the manufacture of different products, including swords, saw blades, springs and many more. These steels are generally low-alloy manganese, medium-carbon steel or high-carbon stee ...

shafts. On December 12, the brothers installed the new shafts on the ''Wright Flyer'' and tested it on their launching rail system that included a wheeled launching dolly. According to Orville:

In practice tests, they were able to achieve a propeller rpm of 351, with a thrust of , more than enough for their flyer.

The ''Wright Flyer'' was a canard biplane configuration, with a wingspan of , a camber of 1-20, a wing area of , and a length of . The right wing was longer because the engine was heavier than Orville or Wilbur. Unoccupied, the machine weighed . As with the gliders, the pilot flew lying on his stomach on the lower wing with his head toward the front of the craft in an effort to reduce drag. The pilot was left of center while the engine was right of center. He steered by moving a hip cradle in the direction he wished to fly. The cradle pulled wires to warp the wings, and simultaneously turn the rudder

A rudder is a primary control surface used to steer a ship, boat, submarine, hovercraft, aircraft, or other vehicle that moves through a fluid medium (generally air or water). On an aircraft the rudder is used primarily to counter adve ...

, for coordinated flight. The pilot operated the elevator lever with his left hand, while holding a strut with his right. The ''Wright Flyer''s "runway" was a track of 2x4s, which the brothers nicknamed the "Junction Railroad". The ''Wright Flyer'' skids rested on a launching dolly, consisting of a plank, with a wheeled wooden section. The two tandem

Tandem, or in tandem, is an arrangement in which a team of machines, animals or people are lined up one behind another, all facing in the same direction.

The original use of the term in English was in ''tandem harness'', which is used for two ...

ball bearing

A ball bearing is a type of rolling-element bearing that uses balls to maintain the separation between the bearing races.

The purpose of a ball bearing is to reduce rotational friction and support radial and axial loads. It achieves this ...

wheels were made from bicycle hubs. A restraining wire held the plane back, while the engine was running and the propellers turning, until the pilot was ready to be released.

The ''Wright Flyer'' had three instruments onboard. A Veeder engine revolution recorder measured the number of propeller turns. A stopwatch recorded the flight time, and a Richard hand anemometer

In meteorology, an anemometer () is a device that measures wind speed and direction. It is a common instrument used in weather stations. The earliest known description of an anemometer was by Italian architect and author Leon Battista Alberti ...

, attached to the front center strut, recorded the distance covered in meters.

Flight trials at Kitty Hawk

Upon returning to Kitty Hawk in 1903, the Wrights completed assembly of the ''Flyer'' while practicing on the 1902 Glider from the previous season. On December 14, 1903, they felt ready for their first attempt at powered flight. With the help of men from the nearby government life-saving station, the Wrights moved the ''Flyer'' and its launching rail to the incline of a nearby sand dune, Big Kill Devil Hill, intending to make a gravity-assisted takeoff. The brothers tossed a coin to decide who would get the first chance at piloting, and Wilbur won. The airplane left the rail, but Wilbur pulled up too sharply, stalled, and came down after covering in 3 seconds, sustaining little damage. Repairs after the abortive first flight took three days. When they were ready again on December 17, the wind was averaging more than , so the brothers laid the launching rail on level ground, pointed into the wind, near their camp. This time the wind, instead of an inclined launch, provided the necessary airspeed for takeoff. Because Wilbur had already had the first chance, Orville took his turn at the controls. His first flight lasted 12 seconds for a total distance of – shorter than the wingspan of aBoeing 747

The Boeing 747 is a large, long-range wide-body airliner designed and manufactured by Boeing Commercial Airplanes in the United States between 1968 and 2022.

After introducing the 707 in October 1958, Pan Am wanted a jet times its size, ...

.

Taking turns, the Wrights made four brief, low-altitude flights that day. The flight paths were all essentially straight; turns were not attempted. Each flight ended in a bumpy and unintended landing. The last flight, by Wilbur, covered in 59 seconds, much longer than each of the three previous flights of 120, 175 and 200 feet (, and ) in 12, 12, and 15 seconds respectively. The fourth flight's landing broke the front elevator supports, which the Wrights hoped to repair for a possible flight to Kitty Hawk village. Soon after, a heavy gust picked up the ''Flyer'' and tumbled it end over end, damaging it beyond any hope of quick repair. It was never flown again.

In 1904, the Wrights continued refining their designs and piloting techniques in order to obtain fully controlled flight. Major progress toward this goal was achieved with a new machine called the

In 1904, the Wrights continued refining their designs and piloting techniques in order to obtain fully controlled flight. Major progress toward this goal was achieved with a new machine called the Wright Flyer II

The Wright Flyer II was the second powered aircraft built by Wilbur and Orville Wright. During 1904 they used it to make a total of 105 flights, ultimately achieving flights lasting five minutes and also making full circles, which was accompl ...

in 1904 and even more decisively in 1905 with the third, Wright Flyer III, in which Wilbur made a 39-minute, nonstop circling flight on October 5.

Influence

The Flyer series of aircraft were the first to achieve controlled heavier-than-air flight, but some of the mechanical techniques the Wrights used to accomplish this were not influential for the development of aviation as a whole, although their theoretical achievements were. The ''Flyer'' design depended on wing-warping controlled by a hip cradle under the pilot, and a foreplane or "canard" for pitch control, features which would not scale and produced a hard-to-control aircraft. The Wrights' pioneering use of "roll control" by twisting the wings to change wingtip angle in relation to the airstream led to the more practical use of

The Flyer series of aircraft were the first to achieve controlled heavier-than-air flight, but some of the mechanical techniques the Wrights used to accomplish this were not influential for the development of aviation as a whole, although their theoretical achievements were. The ''Flyer'' design depended on wing-warping controlled by a hip cradle under the pilot, and a foreplane or "canard" for pitch control, features which would not scale and produced a hard-to-control aircraft. The Wrights' pioneering use of "roll control" by twisting the wings to change wingtip angle in relation to the airstream led to the more practical use of aileron

An aileron (French for "little wing" or "fin") is a hinged flight control surface usually forming part of the trailing edge of each wing of a fixed-wing aircraft. Ailerons are used in pairs to control the aircraft in roll (or movement around ...

s by their imitators, such as Glenn Curtiss

Glenn Hammond Curtiss (May 21, 1878 – July 23, 1930) was an American aviation and motorcycling pioneer, and a founder of the U.S. aircraft industry. He began his career as a bicycle racer and builder before moving on to motorcycles. As early a ...

and Henri Farman. The Wrights' original concept of simultaneous coordinated roll and yaw control (rear rudder deflection), which they discovered in 1902, perfected in 1903–1905, and patented in 1906, represents the solution to controlled flight and is used today on virtually every fixed-wing aircraft. The Wright patent included the use of hinged rather than warped surfaces for the forward elevator and rear rudder. Other features that made the ''Flyer'' a success were highly efficient wings and propellers, which resulted from the Wrights' exacting wind tunnel tests and made the most of the marginal power delivered by their early homebuilt engines; slow flying speeds (and hence survivable accidents); and an incremental test/development approach. The future of aircraft design lay with rigid wings, ailerons and rear control surfaces. A British patent of 1868 for aileron technology had apparently been completely forgotten by the time the 20th century dawned.

After a single statement to the press in January 1904 and a failed public demonstration in May, the Wright Brothers did not publicize their efforts, and other aviators who were working on the problem of flight (notably Alberto Santos-Dumont

Alberto Santos-Dumont ( Palmira, 20 July 1873 — Guarujá, 23 July 1932) was a Brazilian aeronaut, sportsman, inventor, and one of the few people to have contributed significantly to the early development of both lighter-than-air and heavie ...

) were thought by the press to have preceded them by many years. After their successful demonstration flight in France on August 8, 1908, they were accepted as pioneers and received extensive media coverage.

The issue of patent control was correctly seen as critical by the Wrights, and they acquired a wide American patent, intended to give them ownership of basic aerodynamic control. This was fought in both American and European courts. European designers were little affected by the litigation and continued their own development. The legal fight in the U.S. had a crushing effect on the nascent American aircraft industry, and even by the time of America's entry into World War I, in 1917, the U.S. had no suitable military aircraft and had to purchase French and British models.

Stability

The ''Wright Flyer'' was conceived as a control-canard, as the Wrights were more concerned with control than stability. It was found to be unstable and barely controllable. During flight tests near Dayton the Wrights added ballast to the nose of the aircraft to move the center of gravity forward and reduce pitch instability. The Wright Brothers did not understand the basics of pitch stability of the canard configuration. F.E.C. Culick stated, "The backward state of the general theory and understanding of flight mechanics hindered them... Indeed, the most serious gap in their knowledge was probably the basic reason for their unwitting mistake in selecting their canard configuration." According to Combs, "Wright designs incorporated a 'balanced' forward elevator...the movable surface extending an equal distance on both sides of its hinge or pivot axis, as opposed to an 'in-trail' configuration...which would have enhanced controllability in flight." Orville wrote of the elevator, which the brothers called a "front rudder", "I found the control of the front rudder quite difficult on account of its being balanced too near the center and thus had a tendency to turn itself when started so that the rudder was turned too far on one side and then too far on the other." Thus, these early flights suffered from overcontrol.After Kitty Hawk

The Wright Brothers returned home toDayton

Dayton () is the sixth-largest city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Montgomery County. A small part of the city extends into Greene County. The 2020 U.S. census estimate put the city population at 137,644, while Greater Da ...

for Christmas after the flights of the Kitty Hawk ''Flyer''. While they had abandoned their other gliders, they realized the historical significance of the ''Flyer''. They shipped the heavily damaged craft back to Dayton, where it remained stored in crates behind a Wright Company shed for nine years. The Great Dayton Flood

The Great Dayton Flood of 1913 resulted from flooding by the Great Miami River reaching Dayton, Ohio, and the surrounding area, causing the greatest natural disaster in Ohio history. In response, the General Assembly passed the Vonderheide Act to ...

of March 1913 covered the flyer in mud and water for 11 days.

Charlie Taylor relates in a 1948 article that the ''Flyer'' nearly got disposed of by the Wrights. In early 1912 Roy Knabenshue

Augustus Roy Knabenshue (July 15, 1876 – March 6, 1960) was an American aeronautical engineer and aviator.

Biography

Roy Knabenshue was born July 15, 1876, in Lancaster, Ohio, the son of Salome Matlack and Samuel S. Knabenshue. Samue ...

, the Wrights Exhibition team manager, had a conversation with Wilbur and asked Wilbur what they planned to do with the ''Flyer''. Wilbur said they most likely will burn it, as they had the 1904 machine. According to Taylor, Knabenshue talked Wilbur out of disposing of the machine for historical purposes.

In 1910 the Wrights offered the ''Flyer'' as an exhibit at the Smithsonian Institution, but the Smithsonian declined, saying it would be willing to display other aeronautical artifacts from the brothers. Wilbur died in 1912, and in 1916 Orville brought the ''Flyer'' out of storage and prepared it for display at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a private land-grant research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Established in 1861, MIT has played a key role in the development of modern technology and science, and is one of th ...

. He replaced parts of the wing covering, the props, and the engine's crankcase, crankshaft, and flywheel. The crankcase, crankshaft, and flywheel of the original engine had been sent to the Aero Club of America in New York for an exhibit in 1906 and were never returned to the Wrights. The replacement crankcase, crankshaft and flywheel came from the experimental engine Charlie Taylor had built in 1904 and used for testing in the bicycle shop. A replica crankcase of the flyer is on display at the visitor center at the Wright Brothers National Memorial

Wright Brothers National Memorial, located in Kill Devil Hills, North Carolina, commemorates the first successful, sustained, powered flights in a heavier-than-air machine. From 1900 to 1903, Wilbur and Orville Wright came here from Dayton, O ...

.

Debate with the Smithsonian

TheSmithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums and education and research centers, the largest such complex in the world, created by the U.S. government "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge". Found ...

, and primarily its then-secretary Charles Walcott, refused to give credit to the Wright Brothers for the first powered, controlled flight of an aircraft. Instead, they honored the former Smithsonian Secretary Samuel Pierpont Langley

Samuel Pierpont Langley (August 22, 1834 – February 27, 1906) was an American aviation pioneer, astronomer and physicist who invented the bolometer. He was the third secretary of the Smithsonian Institution and a professor of astronomy a ...

, whose 1903 tests of his Aerodrome

An aerodrome (Commonwealth English) or airdrome (American English) is a location from which aircraft flight operations take place, regardless of whether they involve air cargo, passengers, or neither, and regardless of whether it is for publi ...

on the Potomac were not successful. Walcott was a friend of Langley and wanted to see Langley's place in aviation history restored. In 1914, Glenn Curtiss

Glenn Hammond Curtiss (May 21, 1878 – July 23, 1930) was an American aviation and motorcycling pioneer, and a founder of the U.S. aircraft industry. He began his career as a bicycle racer and builder before moving on to motorcycles. As early a ...

had recently exhausted the appeal process in a patent infringement legal battle with the Wrights. Curtiss sought to prove Langley's machine, which failed piloted tests nine days before the Wrights' successful flight in 1903, capable of controlled, piloted flight in an attempt to invalidate the Wrights' wide-sweeping patents.

The Aerodrome was removed from exhibit at the Smithsonian and prepared for flight at Keuka Lake, New York. Curtiss called the preparations "restoration" claiming that the only addition to the design was pontoons to support testing on the lake but critics including patent attorney Griffith Brewer called them alterations of the original design. Curtiss flew the modified ''Aerodrome'', hopping a few feet off the surface of the lake for 5 seconds at a time.

Between 1916 and 1928, the ''Wright Flyer'' was prepared and assembled for exhibition under the supervision of Orville by Wright Company mechanic Jim Jacobs several times. It was briefly exhibited at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1916, the New York Aero Shows in 1917 and 1919, a Society of Automotive Engineers

SAE International, formerly named the Society of Automotive Engineers, is a United States-based, globally active professional association and standards developing organization for engineering professionals in various industries. SAE Internatio ...

meeting in Dayton, Ohio in 1918, and the National Air Races

The National Air Races (also known as Pulitzer Trophy Races) are a series of pylon and cross-country races that have taken place in the United States since 1920. The science of aviation, and the speed and reliability of aircraft and engines grew ...

in Dayton in 1924.

In 1925, Orville attempted to pressure the Smithsonian by warning that he would send the ''Flyer'' to the Science Museum

A science museum is a museum devoted primarily to science. Older science museums tended to concentrate on static displays of objects related to natural history, paleontology, geology, industry and industrial machinery, etc. Modern trends in ...

in London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

if the Institution refused to recognize his and Wilbur's accomplishment. The threat did not achieve its intended effect, and on January 28, 1928, Orville shipped the ''Kitty Hawk'' to London for display at the museum. It remained there in "the place of honour", except during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

when it was moved to an underground storage facility away, near Corsham

Corsham is a historic market town and civil parish in west Wiltshire, England. It is at the south-eastern edge of the Cotswolds, just off the A4 national route, southwest of Swindon, southeast of Bristol, northeast of Bath and southwest of ...

.

In 1942, the Smithsonian Institution, under a new secretary, Charles Abbot, published a list of 35 Curtiss modifications to the ''Aerodrome'' and a retraction of its long-held claims for the craft. Abbot went on to list four regrets including the role the Institution played in supporting unsuccessful defendants in patent litigation by the Wrights, misinformation about modifications made to the Aerodrome after ''Wright Flyer''s first flight, and public statements attributing the "first aeroplane capable of sustained free flight with a man" to Secretary Langley. The entry in the 1942 Annual Report of Smithsonian Institution begins with the statement "It is everywhere acknowledged that the Wright brothers were the first to make sustained flights in a heavier-than-air machine at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, on December 17, 1903" and closes with a promise that "Should Dr. Wright decide to deposit the plane ... it would be given the highest place of honor which it is due"

The following year, Orville, after exchanging several letters with Abbott, agreed to return the ''Flyer'' to the United States. The ''Flyer'' stayed at the Science Museum until a replica could be built, based on the original. This change of heart by the Smithsonian is also mired in controversy – the ''Flyer'' was sold to the Smithsonian under several contractual conditions, one of which reads:

On October 18, 1948, the official handover of the ''Kitty Hawk'' was made to Livingston L. Satterthwaite, the American Civil Air Attaché at a ceremony attended by representatives of the various flying organizations in the UK and by some British aviation pioneers such as Sir Alliott Verdon-Roe

Sir Edwin Alliott Verdon Roe OBE, Hon. FRAeS, FIAS (26 April 1877 – 4 January 1958) was a pioneer English pilot and aircraft manufacturer, and founder in 1910 of the Avro company. After experimenting with model aeroplanes, he made flight tr ...

.

On November 11, 1948, the ''Kitty Hawk'' arrived in North America onboard the ''Mauretania

Mauretania (; ) is the Latin name for a region in the ancient Maghreb. It stretched from central present-day Algeria westwards to the Atlantic, covering northern present-day Morocco, and southward to the Atlas Mountains. Its native inhabitants ...

'' with 1,111 passengers. When the liner docked at Halifax, Nova Scotia

Halifax is the capital and largest municipality of the Canadian province of Nova Scotia, and the largest municipality in Atlantic Canada. As of the 2021 Census, the municipal population was 439,819, with 348,634 people in its urban area. Th ...

, Paul E. Garber of the Smithsonian's National Air Museum met the aircraft and took command of the proceedings, overseeing its transfer to the US Navy aircraft carrier, the USS ''Palau'', which repatriated the aircraft by way of New York Harbor. The rest of the journey to Washington continued on flatbed truck. While in Halifax Garber met John A. D. McCurdy, at the time the Lieutenant Governor of Nova Scotia. McCurdy as a young man had been a member of Alexander Graham Bell's team Aerial Experiment Association

The Aerial Experiment Association (AEA) was a Canadian-American aeronautical research group formed on 30 September 1907, under the leadership of Dr. Alexander Graham Bell.

The AEA produced several different aircraft in quick succession, with eac ...

, which included Glenn Curtiss, and later a famous pioneer pilot. During the stay at Halifax, Garber and McCurdy reminisced about the pioneer aviation days and the Wright Brothers. McCurdy also offered Garber any assistance he needed to get the ''Flyer'' home.

In the Smithsonian

The ''Wright Flyer'' was put on display in the Arts and Industries Building of the Smithsonian on December 17, 1948, 45 years to the day after the aircraft's only successful flights. (Orville did not live to see this, as he had died that January.) In 1976, it was moved to the Milestones of Flight Gallery of the newNational Air and Space Museum

The National Air and Space Museum of the Smithsonian Institution, also called the Air and Space Museum, is a museum in Washington, D.C., in the United States.

Established in 1946 as the National Air Museum, it opened its main building on the N ...

. Since 2003 it has resided in a special exhibit in the museum titled "The Wright Brothers and the Invention of the Aerial Age," in recognition of the 100th anniversary of their first flight.

1985 restoration

In 1981, discussion began on the need to restore the ''Wright Flyer'' from the aging it sustained after many decades on display. During the ceremonies celebrating the 78th anniversary of the first flights, Mrs. Harold S. Miller (Ivonette Wright, Lorin's daughter), one of the Wright brothers' nieces, presented the Museum with the original covering of one wing of the ''Flyer'', which she had received in her inheritance from Orville. She expressed her wish to see the aircraft restored.Mikesh. The fabric covering on the aircraft at the time, which came from the 1927 restoration, was discolored and marked with water spots. Metal fasteners holding the wing uprights together had begun to corrode, marking the nearby fabric. Work began in 1985. The restoration was supervised by Senior Curator Robert Mikesh and assisted by Wright Brothers expert Tom Crouch. Museum directorWalter J. Boyne

Walter J. Boyne (February 2, 1929 – January 9, 2020) was a United States Air Force officer, Command Pilot, combat veteran, aviation historian, and author of more than 50 books and over 1,000 magazine articles. He was a director of the National A ...

decided to perform the restoration in full view of the public.

The wooden framework was cleaned, and corrosion on metal parts removed. The covering was the only part of the aircraft replaced. The new covering was more accurate to the original than that of the 1927 restoration. To preserve the original paint on the engine, the restorers coated it in inert wax before putting on a new coat of paint. The effects of the 1985 restoration were intended to last 75 years (to 2060) before another restoration would be required.

Reproductions

In 1978, 23-year-old Ken Kellett built a replica ''Wright Flyer'' in Colorado and flew it at Kitty Hawk on the 75th and 80th anniversaries of the first flight there. Construction took a year and cost $3,000. As the 100th anniversary on December 17, 2003, approached, the U.S. Centennial of Flight Commission along with other organizations opened bids for companies to recreate the original flight. The Wright Experience, led by Ken Hyde, won the bid and painstakingly recreated reproductions of the original ''Wright Flyer'', plus many of the prototype gliders and kites and subsequent Wright aircraft. The completed ''Flyer'' reproduction was brought to Kitty Hawk and pilot Kevin Kochersberger attempted to recreate the original flight at 10:35 on December 17, 2003, on level ground near the bottom of Kill Devil Hill. Although the aircraft had previously made several successful test flights, poor weather, rain, and weak winds prevented a successful flight on the anniversary. Hyde's reproduction is displayed at the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Michigan. The Los Angeles Section of the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AIAA) built a full-scale replica of the 1903 ''Wright Flyer'' between 1979 and 1993 using plans from the original ''Wright Flyer'' published by the Smithsonian Institution in 1950. Constructed in advance of the 100th anniversary of the Wright Brothers' first flight, the replica was intended for wind tunnel testing to provide a historically accurate aerodynamic database of the ''Wright Flyer'' design. The aircraft went on display at the March Field Air Museum in Riverside, California. Numerous static display-only, nonflying reproductions are on display around the United States and across the world, making this perhaps the most reproduced single aircraft of the "pioneer" era in history, rivaling the number of copies – some of which are airworthy – ofLouis Blériot

Louis Charles Joseph Blériot ( , also , ; 1 July 1872 – 1 August 1936) was a French aviator, inventor, and engineer. He developed the first practical headlamp for cars and established a profitable business manufacturing them, using much of th ...

's cross-Channel Bleriot XI from 1909.

NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agency of the US federal government responsible for the civil space program, aeronautics research, and space research.

NASA was established in 1958, succeedin ...

wind tunnel

File:15 23 1065 wright flyer replica.jpg, ''Wright Flyer'' Replica at the Henry Ford Museum

The Henry Ford (also known as the Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation and Greenfield Village, and as the Edison Institute) is a history museum complex in the Detroit suburb of Dearborn, Michigan, United States. The museum collection contains ...

File:Frontiers of Flight Museum December 2015 109 (1903 Wright Flyer model).jpg, ''Flyer'' replica at the Frontiers of Flight Museum

Frontiers may refer to:

* Frontier, areas near or beyond a boundary

Arts and entertainment Music

* ''Frontiers'' (Journey album), 1983

* ''Frontiers'' (Jermaine Jackson album), 1978

* ''Frontiers'' (Jesse Cook album), 2007

* ''Frontiers'' (P ...

File:1903 Wright Flyer Fleming.jpg, 1903 ''Wright Flyer'' replica at the Lysdale Historic HangaFile:JAM Wright Flyer.png, ''Wright Flyer'' replica at Jeju Aerospace Museum

Artifacts

In 1969, portions of the original fabric and wood from the ''Wright Flyer'' traveled to the Moon and its surface inNeil Armstrong

Neil Alden Armstrong (August 5, 1930 – August 25, 2012) was an American astronaut and aeronautical engineer who became the first person to walk on the Moon in 1969. He was also a naval aviator, test pilot, and university professor.

...

's personal preference kit aboard the Apollo 11

Apollo 11 (July 16–24, 1969) was the American spaceflight that first landed humans on the Moon. Commander Neil Armstrong and lunar module pilot Buzz Aldrin landed the Apollo Lunar Module ''Eagle'' on July 20, 1969, at 20:17 UTC, ...

Lunar Module ''Eagle'', and then back to Earth in the Command module ''Columbia''.

This artifact is on display at the visitors center at the Wright Brothers National Memorial

Wright Brothers National Memorial, located in Kill Devil Hills, North Carolina, commemorates the first successful, sustained, powered flights in a heavier-than-air machine. From 1900 to 1903, Wilbur and Orville Wright came here from Dayton, O ...

in Kitty Hawk, North Carolina.

In 1986, separate portions of original wood and fabric, as well as a note by Orville Wright, were taken by North Carolina native astronaut Michael Smith aboard the Space Shuttle ''Challenger'' on mission STS-51-L

STS-51-L was the 25th mission of the NASA Space Shuttle program and the final flight of Space Shuttle ''Challenger''.

Planned as the first Teacher in Space Project flight in addition to observing Halley's Comet for six days and performing a ...

, which was destroyed soon after liftoff. The portions of wood and fabric and Wright's note were recovered from the wreck of the Shuttle and are on display at the North Carolina Museum of History

The North Carolina Museum of History is a history museum located in downtown Raleigh, North Carolina. It is an affiliate through the Smithsonian Affiliations program. The museum is a part of the Division of State History Museums, Office of Archives ...

.

A small piece of the ''Wright Flyer''s wing fabric is attached to a cable underneath the solar panel of the helicopter '' Ingenuity'', which became the first vehicle to perform a controlled atmospheric flight on Mars on April 19, 2021. Before moving on for further exploration and testing, ''Ingenuity''s first base on Mars was named Wright Brothers Field

''Ingenuity,'' nicknamed ''Ginny,'' is a small robotic helicopter operating on Mars as part of NASA's Mars 2020 mission along with the ''Perseverance'' rover, which landed with ''Ingenuity'' attached to its underside on February 18, 2021 ...

.

Neil Armstrong

Neil Alden Armstrong (August 5, 1930 – August 25, 2012) was an American astronaut and aeronautical engineer who became the first person to walk on the Moon in 1969. He was also a naval aviator, test pilot, and university professor.

...

aboard Apollo 11

Apollo 11 (July 16–24, 1969) was the American spaceflight that first landed humans on the Moon. Commander Neil Armstrong and lunar module pilot Buzz Aldrin landed the Apollo Lunar Module ''Eagle'' on July 20, 1969, at 20:17 UTC, ...

and flown to the surface in the Lunar Module ''Eagle''

File:Wright flyer fragments STS-51-L.jpg, ''Wright Flyer'' wood, fabric, and a note by Orville Wright taken aboard Space Shuttle ''Challenger'''s 1986 flight STS-51-L

STS-51-L was the 25th mission of the NASA Space Shuttle program and the final flight of Space Shuttle ''Challenger''.

Planned as the first Teacher in Space Project flight in addition to observing Halley's Comet for six days and performing a ...

, which exploded soon after liftoff

File:PIA23882-MarsHelicopterIngenuity-20200429 (trsp).png, A piece of ''Wright Flyer''s wing fabric is attached to the '' Ingenuity'' helicopter, the first powered aircraft to fly on Mars

Specifications

See also

References

Notes

Bibliography

* * Hallion, Richard P. ''The Wright Brothers: Heirs of Prometheus''. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian, 1978. . * Hise, Phaedra. "In Search of the Real Wright Flyer." ''Air&Space/Smithsonian'', January 2003, pp. 22–29. * Howard, Fred. ''Orville and Wilbur: The Story of the Wright Brothers''. London: Hale, 1988. . * Jakab, Peter L. "The Original." ''Air&Space/Smithsonian'', March 2003, pp. 34–39. * Mikesh, Robert C. and Tom D. Crouch. "Restoration: The Wright Flyer." ''National Air and Space Museum Research Report'', 1985, pp. 135–141. *External links

Nasa.gov

Wrightflyer.org

Wrightexperience.com

''Air & Space Magazine''

1942 Smithsonian Annual Report acknowledging primacy of the ''Wright Flyer''

History of the ''Wright Flyer''

Wright State University Library {{Authority control 1903 in North Carolina Aircraft first flown in 1903 Articles containing video clips Canard aircraft History of Dayton, Ohio Individual aircraft in the collection of the Smithsonian Institution Prone pilot aircraft Single-engined twin-prop pusher aircraft 1900s United States experimental aircraft Flyer Aircraft with counter-rotating propellers