Works Progress Administration on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Works Progress Administration (WPA; from 1935 to 1939, then known as the Work Projects Administration from 1939 to 1943) was an American New Deal agency that employed millions of jobseekers (mostly men who were not formally educated) to carry out

The goal of the WPA was to employ most of the unemployed people on relief until the economy recovered.

The goal of the WPA was to employ most of the unemployed people on relief until the economy recovered.  Because of the assumption that only one worker per family would be permitted to work under the proposed program, this total of 5.15 million was further reduced by 1.6 million—the estimated number of workers who were members of families with two or more employable people. Thus, there remained a net total of 3.55 million workers in as many households for whom jobs were to be provided.

The WPA reached its peak employment of 3,334,594 people in November 1938. To be eligible for WPA employment, an individual had to be an American citizen, 18 or older, able-bodied, unemployed, and certified as in need by a local public relief agency approved by the WPA. The WPA Division of Employment selected the worker's placement to WPA projects based on previous experience or training. Worker pay was based on three factors: the region of the country, the degree of

Because of the assumption that only one worker per family would be permitted to work under the proposed program, this total of 5.15 million was further reduced by 1.6 million—the estimated number of workers who were members of families with two or more employable people. Thus, there remained a net total of 3.55 million workers in as many households for whom jobs were to be provided.

The WPA reached its peak employment of 3,334,594 people in November 1938. To be eligible for WPA employment, an individual had to be an American citizen, 18 or older, able-bodied, unemployed, and certified as in need by a local public relief agency approved by the WPA. The WPA Division of Employment selected the worker's placement to WPA projects based on previous experience or training. Worker pay was based on three factors: the region of the country, the degree of

Directed by Nikolai Sokoloff, former principal conductor of the Cleveland Orchestra, the Federal Music Project employed over 16,000 musicians at its peak. Its purpose was to create jobs for unemployed musicians, It established new ensembles such as chamber groups, orchestras, choral units, opera units, concert bands, military bands, dance bands, and theater orchestras. They gave 131,000 performances and programs to 92 million people each week. The Federal Music Project performed plays and dances, as well as radio dramas. In addition, the Federal Music Project gave music classes to an estimated 132,000 children and adults every week, recorded folk music, served as copyists, arrangers, and librarians to expand the availability of music, and experimented in music therapy. Sokoloff stated, "Music can serve no useful purpose unless it is heard, but these totals on the listeners' side are more eloquent than statistics as they show that in this country there is a great hunger and eagerness for music."

Directed by Nikolai Sokoloff, former principal conductor of the Cleveland Orchestra, the Federal Music Project employed over 16,000 musicians at its peak. Its purpose was to create jobs for unemployed musicians, It established new ensembles such as chamber groups, orchestras, choral units, opera units, concert bands, military bands, dance bands, and theater orchestras. They gave 131,000 performances and programs to 92 million people each week. The Federal Music Project performed plays and dances, as well as radio dramas. In addition, the Federal Music Project gave music classes to an estimated 132,000 children and adults every week, recorded folk music, served as copyists, arrangers, and librarians to expand the availability of music, and experimented in music therapy. Sokoloff stated, "Music can serve no useful purpose unless it is heard, but these totals on the listeners' side are more eloquent than statistics as they show that in this country there is a great hunger and eagerness for music."

File:Little Miss Muffet 1940 poster.jpg, 1940 WPA poster using '' Little Miss Muffet'' to promote reading among children

File:WPA-Cancer-Poster-Herzog.jpg, WPA health education poster about cancer, –1938

File:The nickel and dime store, WPA poster, ca. 1941.jpg, Poster for the WPA shows various items that can be purchased at the 5 & 10¢ store

File:Art classes for children LCCN98510141.jpg, WPA poster advertising art classes for children

File:WPA_Zoo_Poster-Elephant.jpg, WPA poster promoting the zoo as a place to visit, showing an elephant

File:WPA_Theatre_Poster-Abraham_Lincoln.jpg, 1936 WPA Poster for Federal Theatre Project presentation

File:WPA-Work-Pays-America-Poster.jpg, WPA poster encouraging laborers to work for America

About 15% of the household heads on relief were women, and youth programs were operated separately by the

About 15% of the household heads on relief were women, and youth programs were operated separately by the

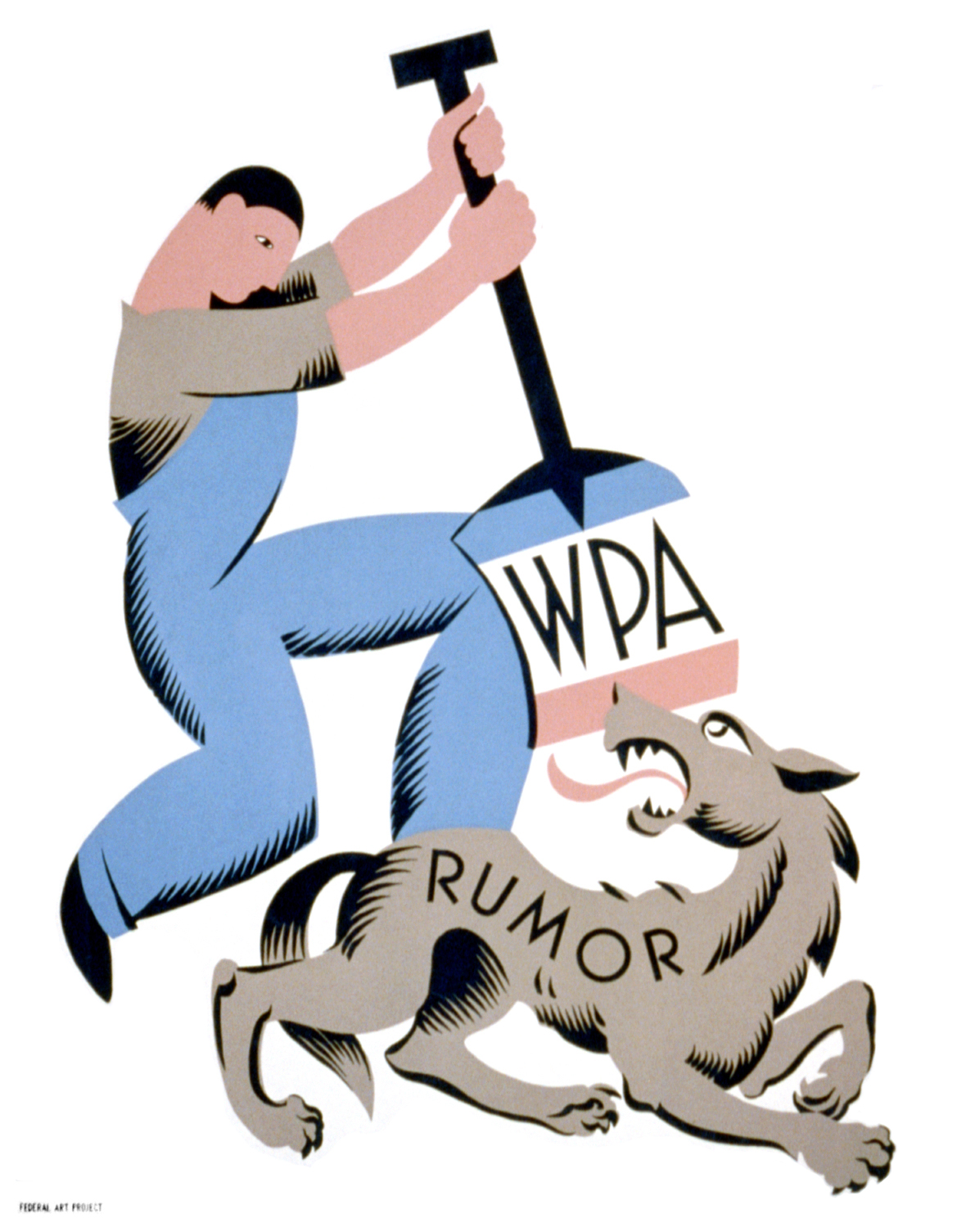

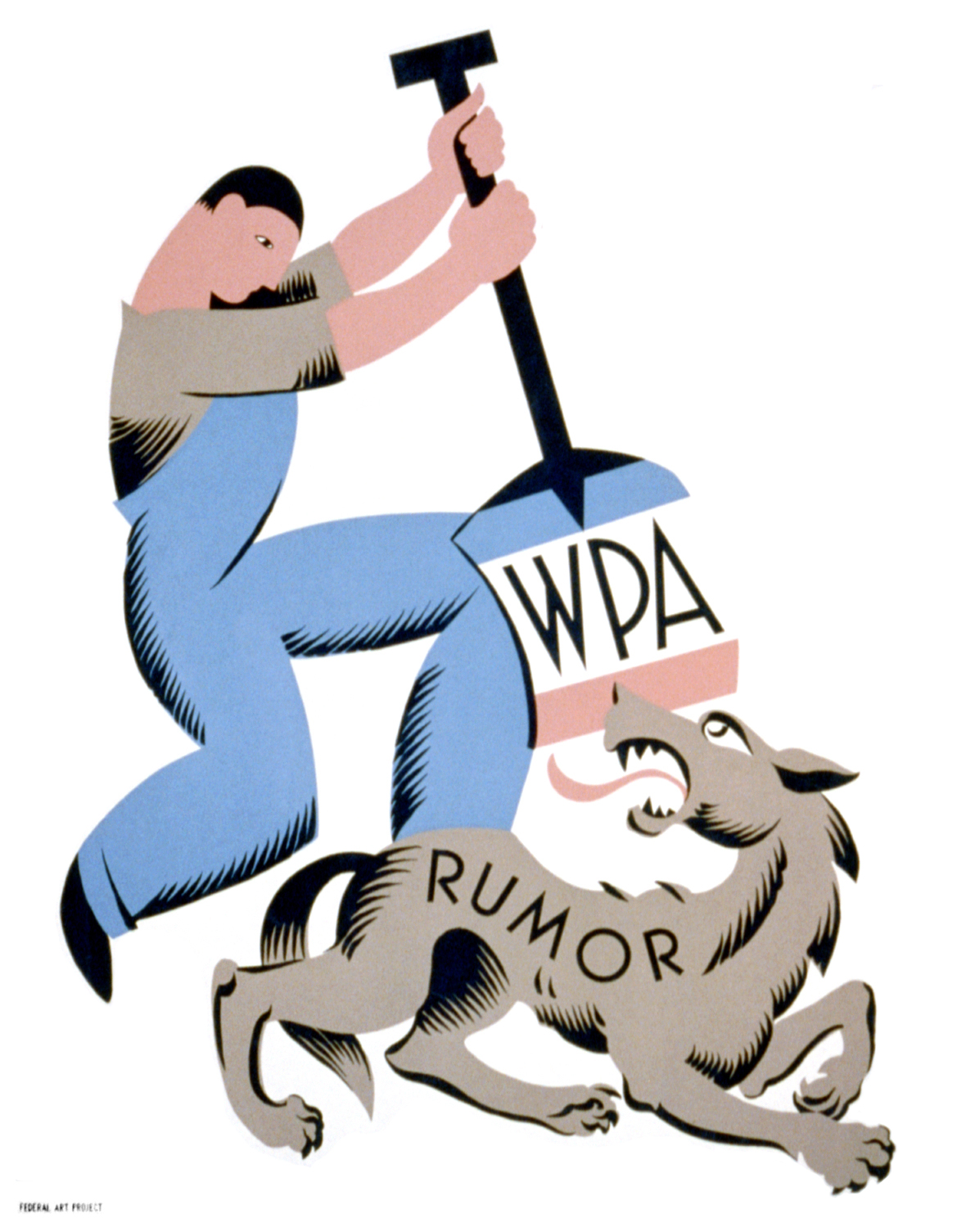

The WPA had numerous critics. The strongest attacks were that it was the prelude for a national political machine on behalf of Roosevelt. Reformers secured the Hatch Act of 1939 that largely depoliticized the WPA.

Others complained that far left elements played a major role, especially in the New York City unit. Representative J. Parnell Thomas of the House Committee on Un-American Activities claimed in 1938 that divisions of the WPA were a "hotbed of Communists" and "one more link in the vast and unparalleled New Deal propaganda network."

Much of the criticism of the distribution of projects and funding allotment is a result of the view that the decisions were politically motivated. The South, despite being the poorest region of the United States, received 75% less in federal relief and public works funds per capita than the West. Critics would point to the fact that Roosevelt's Democrats could be sure of voting support from the South, whereas the West was less of a sure thing;

The WPA had numerous critics. The strongest attacks were that it was the prelude for a national political machine on behalf of Roosevelt. Reformers secured the Hatch Act of 1939 that largely depoliticized the WPA.

Others complained that far left elements played a major role, especially in the New York City unit. Representative J. Parnell Thomas of the House Committee on Un-American Activities claimed in 1938 that divisions of the WPA were a "hotbed of Communists" and "one more link in the vast and unparalleled New Deal propaganda network."

Much of the criticism of the distribution of projects and funding allotment is a result of the view that the decisions were politically motivated. The South, despite being the poorest region of the United States, received 75% less in federal relief and public works funds per capita than the West. Critics would point to the fact that Roosevelt's Democrats could be sure of voting support from the South, whereas the West was less of a sure thing;

On December 23, 1938, after leading the WPA for three and a half years,

On December 23, 1938, after leading the WPA for three and a half years,  On May 26, 1940, FDR delivered a fireside chat to the American people about "the approaching storm", and on June 6 Harrington reprioritized WPA projects, anticipating a major expansion of the U.S. military. "Types of WPA work to be expedited in every possible way to include, in addition to airports and military airfields, construction of housing and other facilities for enlarged military garrisons, camp and cantonment construction, and various improvements in navy yards," Harrington said. He observed that the WPA had already made substantial contributions to national defense over its five years of existence, by building 85 percent of the new airports in the U.S. and making $420 million in improvements to military facilities. He predicted there would be 500,000 WPA workers on defense-related projects over the next 12 months, at a cost of $250 million. The estimated number of WPA workers needed for defense projects was soon revised to between 600,000 and 700,000. Vocational training for war industries was also begun by the WPA, with 50,000 trainees in the program by October 1940.

"Only the WPA, having employed millions of relief workers for more than five years, had a comprehensive awareness of the skills that would be available in a full-scale national emergency," wrote journalist Nick Taylor. "As the country began its preparedness buildup, the WPA was uniquely positioned to become a major defense agency."

Harrington died suddenly, aged 53, on September 30, 1940. Notably apolitical—he boasted that he had never voted—he had deflected Congressional criticism of the WPA by bringing attention to its building accomplishments and its role as an employer. Harrington's successor, Howard O. Hunter, served as head of the WPA until May 1, 1942.

On May 26, 1940, FDR delivered a fireside chat to the American people about "the approaching storm", and on June 6 Harrington reprioritized WPA projects, anticipating a major expansion of the U.S. military. "Types of WPA work to be expedited in every possible way to include, in addition to airports and military airfields, construction of housing and other facilities for enlarged military garrisons, camp and cantonment construction, and various improvements in navy yards," Harrington said. He observed that the WPA had already made substantial contributions to national defense over its five years of existence, by building 85 percent of the new airports in the U.S. and making $420 million in improvements to military facilities. He predicted there would be 500,000 WPA workers on defense-related projects over the next 12 months, at a cost of $250 million. The estimated number of WPA workers needed for defense projects was soon revised to between 600,000 and 700,000. Vocational training for war industries was also begun by the WPA, with 50,000 trainees in the program by October 1940.

"Only the WPA, having employed millions of relief workers for more than five years, had a comprehensive awareness of the skills that would be available in a full-scale national emergency," wrote journalist Nick Taylor. "As the country began its preparedness buildup, the WPA was uniquely positioned to become a major defense agency."

Harrington died suddenly, aged 53, on September 30, 1940. Notably apolitical—he boasted that he had never voted—he had deflected Congressional criticism of the WPA by bringing attention to its building accomplishments and its role as an employer. Harrington's successor, Howard O. Hunter, served as head of the WPA until May 1, 1942.

File:COMPANY E OF THE 167TH INFANTRY OF THE ALABAMA NATIONAL GUARD ARMORY; MARSHALL COUNTY,.jpg, Alabama National Guard Armory,  Natrona County High School,

Natrona County High School,

online

* Hopkins, June. "The Road Not Taken: Harry Hopkins and New Deal Work Relief" ''Presidential Studies Quarterly'' 29#2 (1999): 306–1

online

* Howard, Donald S. ''WPA and federal relief policy'' (1943), 880pp; highly detailed report by the independent Russell Sage Foundation

online

* Kelly, Andrew, ''Kentucky by Design: The Decorative Arts, American Culture and the Arts Programs of the WPA.'' Lexington: University Press of Kentucky. 2015. * Larson, Cedric. "The Cultural Projects of the WPA." ''The Public Opinion Quarterly'' 3#3 (1939): 491–196. Accesse

in JSTOR

* Leighninger, Robert D. "Cultural Infrastructure: The Legacy of New Deal Public Space." '' Journal of Architectural Education'' 49, no. 4 (1996): 226–236. * Leighninger, Robert D. Jr. ''Long-Range Public Investment: the Forgotten Legacy of the New Deal''. Columbia, S.C.: University of South Carolina Press (2007). * Lindley, Betty Grimes & Lindley, Ernest K. ''A New Deal for Youth: the Story of the National Youth Administration'' (1938) * McJimsey George T. ''Harry Hopkins: Ally of the Poor and Defender of Democracy'' (1987

online

* Mathews, Jane DeHart. ''Federal Theatre, 1935–1939: Plays, Relief, and Politics'' (Princeton UP 1967

online

* Meriam; Lewis. ''Relief and Social Security''. (The Brookings Institution, 1946)

online

900pp * Millett; John D. & Gladys Ogden. ''Administration of Federal Work Relief'' 1941. * Musher, Sharon Ann. ''Democratic Art: The New Deal's Influence on American Culture.'' (University of Chicago Press, 2015_. * Rose, Nancy. ''Put to Work: The WPA and Public Employment in the Great Depression'' (2009), brief introduction * Sargent, James E. "Woodrum's Economy Bloc: The Attack on Roosevelt's WPA, 1937–1939." ''Virginia Magazine of History and Biography'' (1985): 175–207

in JSTOR

* Sheppard, Si. " 'If it wasn't for Roosevelt you wouldn't have this job': The Politics of Patronage and the 1936 Presidential Election in New York." New York History 95.1 (2014): 41–69.

excerpt

* Singleton, Jeff. ''The American Dole: Unemployment Relief and the Welfare State in the Great Depression'' (2000) * Smith, Jason Scott. ''Building New Deal Liberalism: the Political Economy of Public Works, 1933–1956'' (2005) * Taylor, David A. ''Soul of a People: The WPA Writers' Project Uncovers Depression America''. (2009) * Taylor, Nick. ''American-Made: The Enduring Legacy of the WPA: When FDR Put the Nation to Work'' (2008) comprehensive history; 640p

excerpt

* Williams, Edward Ainsworth. ''Federal aid for relief'' (Columbia University Press, 1939

online

* Young, William H., & Nancy K. ''The Great Depression in America: a Cultural Encyclopedia''. 2 vols. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 2007

at

Footage of the Federal Theatre Project's 1936 "Voodoo Macbeth"

– with informative annotations. * The Great Depression in Washington State Project, including an illustrated map o

major WPA projects

and a multimedia history of th

Federal Theater Project

in the State.

The Index of American Design

at the National Gallery of Art * * *

Guide to the WPA Oregon Federal Art Project collection at the University of Oregon

WPA inspired Gulf Coast Civic Works Project

Living New Deal Project

– The Living New Deal Project documents the living legacy of New Deal agencies, including the WPA. The Living New Deal website includes an extensive digital map featuring detailed information about specific WPA projects by location.

Soul of a People documentary

on Smithsonian Networks

Works Progress Administration Tampa Office Records

at th

University of South Florida

Arizona Archives Online Finding Aid

– The Arizona State Museum Library & Archives holds the records of the WPA Statewide Archaeological Project (1938–1940) and are found on AAO.

WPA Art Inventory Project

at the

WPA Omaha, Nebraska City Guide Project

by the University of Nebraska Omaha Dr. C.C. and Mabel L. Criss Library. * WPA publications fro

AlabamaFloridaGeorgiaKentuckyLouisianaMarylandNorth Carolina

an

Tennessee

housed at the University of Kentucky Libraries Special Collections Research Center

Tapestries

a

A History of Central Florida Podcast

WPA digital collection

at the New York Public Library

WPA Music Manuscripts

at

United States Work Projects Administration Polar Bibliography

at Dartmouth College Library

Work Projects Administration in Maryland records

at the

Collection: "Art of the Works Progress Administration WPA"

from the University of Michigan Museum of Art WPA posters:

Posters from the WPA at the Library of Congress

Libraries and the WPA:

South Carolina Public Library History, 1930–1945

WPA Children's Books (1935–1943)

Broward County Library's Bienes Museum of the Modern Book WPA murals:

Database of WPA murals

WPA-FAP Mural Division in NYC, and restoration of murals at the Williamsburg Houses and Hospital for Chronic Diseases on Welfare Island

WPA mural projects

by noted muralist Sr. Lucia Wiley

WPA Artist Louis Schanker

Robert Tabor {{Authority control New Deal agencies Defunct agencies of the United States government History of the government of the United States Former United States Federal assistance programs 1935 establishments in Washington, D.C. Government agencies established in 1935 Government agencies disestablished in 1943 1943 disestablishments in Washington, D.C. Great Depression in the United States Work relief programs

public works

Public works are a broad category of infrastructure projects, financed and procured by a government body for recreational, employment, and health and safety uses in the greater community. They include public buildings ( municipal buildings, ...

projects, including the construction of public buildings and roads. It was set up on May 6, 1935, by presidential order, as a key part of the Second New Deal.

The WPA's first appropriation in 1935 was $4.9 billion (about $15 per person in the U.S., around 6.7 percent of the 1935 GDP). Headed by Harry Hopkins

Harold Lloyd Hopkins (August 17, 1890 – January 29, 1946) was an American statesman, public administrator, and presidential advisor. A trusted deputy to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Hopkins directed New Deal relief programs before ser ...

, the WPA supplied paid jobs to the unemployed during the Great Depression in the United States

In the United States, the Great Depression began with the Wall Street Crash of October 1929 and then spread worldwide. The nadir came in 1931–1933, and recovery came in 1940. The stock market crash marked the beginning of a decade of high u ...

, while building up the public infrastructure of the US, such as parks, schools, and roads. Most of the jobs were in construction, building more than of streets and over 10,000 bridges, in addition to many airports and much housing. In 1942, the WPA played a key role in both building and staffing internment camps to incarcerate Japanese Americans.

At its peak in 1938, it supplied paid jobs for three million unemployed men and women, as well as youth in a separate division, the National Youth Administration

The National Youth Administration (NYA) was a New Deal agency sponsored by Presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt, Franklin D. Roosevelt during his presidency. It focused on providing work and education for Americans between the ages of 16 and 25. ...

. Between 1935 and 1943, the WPA employed 8.5 million people (about half the population of New York). Hourly wages were typically kept well below industry standards. Full employment, which was reached in 1942 and appeared as a long-term national goal around 1944, was not the goal of the WPA; rather, it tried to supply one paid job for all families in which the breadwinner suffered long-term unemployment.

In one of its most famous projects, Federal Project Number One, the WPA employed musicians, artists, writers, actors and directors in arts, drama, media, and literacy projects. The five projects dedicated to these were the Federal Writers' Project

The Federal Writers' Project (FWP) was a federal government project in the United States created to provide jobs for out-of-work writers and to develop a history and overview of the United States, by state, cities and other jurisdictions. It was ...

(FWP), the Historical Records Survey (HRS), the Federal Theatre Project (FTP), the Federal Music Project (FMP), and the Federal Art Project (FAP). In the Historical Records Survey, for instance, many former slaves in the South were interviewed; these documents are of immense importance to American history. Theater and music groups toured throughout the United States and gave more than 225,000 performances. Archaeological investigations under the WPA were influential in the rediscovery of pre-Columbian Native American cultures, and the development of professional archaeology in the US.

The WPA was a federal program that ran its own projects in cooperation with state

State most commonly refers to:

* State (polity), a centralized political organization that regulates law and society within a territory

**Sovereign state, a sovereign polity in international law, commonly referred to as a country

**Nation state, a ...

and local

Local may refer to:

Geography and transportation

* Local (train), a train serving local traffic demand

* Local, Missouri, a community in the United States

Arts, entertainment, and media

* ''Local'' (comics), a limited series comic book by Bria ...

governments, which supplied 10–30% of the costs. Usually, the local sponsor provided land and often trucks and supplies, with the WPA responsible for wages (and for the salaries of supervisors, who were not on relief). WPA sometimes took over state and local relief programs that had originated in the Reconstruction Finance Corporation

The Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) was an Independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the United States federal government that served as a lender of last resort to US banks and businesses. Established in ...

(RFC) or Federal Emergency Relief Administration

The Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) was a program established by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1933, building on the Hoover administration's Emergency Relief and Construction Act. It was replaced in 1935 by the Works Progre ...

programs (FERA). It was liquidated on June 30, 1943, because of low unemployment during World War II. Robert D. Leininger asserted: "millions of people needed subsistence incomes. Work relief was preferred over public assistance (the dole) because it maintained self-respect, reinforced the work ethic, and kept skills sharp."

Establishment

On May 6, 1935, FDR issuedexecutive order

In the United States, an executive order is a directive by the president of the United States that manages operations of the federal government. The legal or constitutional basis for executive orders has multiple sources. Article Two of the ...

7034, establishing the Works Progress Administration. The WPA superseded the work of the Federal Emergency Relief Administration

The Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) was a program established by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1933, building on the Hoover administration's Emergency Relief and Construction Act. It was replaced in 1935 by the Works Progre ...

, which was dissolved. Direct relief assistance was permanently replaced by a national work relief program—a major public works

Public works are a broad category of infrastructure projects, financed and procured by a government body for recreational, employment, and health and safety uses in the greater community. They include public buildings ( municipal buildings, ...

program directed by the WPA.

The WPA was largely shaped by Harry Hopkins

Harold Lloyd Hopkins (August 17, 1890 – January 29, 1946) was an American statesman, public administrator, and presidential advisor. A trusted deputy to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Hopkins directed New Deal relief programs before ser ...

, supervisor of the Federal Emergency Relief Administration and close adviser to Roosevelt. Both Roosevelt and Hopkins believed that the route to economic recovery and the lessened importance of the dole would be in employment programs such as the WPA. Hallie Flanagan

Hallie Flanagan Davis (August 27, 1889 – June 23, 1969) was an American theatrical producer and director, playwright, and author, best known as director of the Federal Theatre Project, a part of the Works Progress Administration (WPA).

B ...

, national director of the Federal Theatre Project, wrote that "for the first time in the relief experiments of this country the preservation of the skill of the worker, and hence the preservation of his self-respect, became important."

The WPA was organized into the following divisions:

* The Division of Engineering and Construction, which planned and supervised construction projects including airports, dams, highways and sanitation systems.

* The Division of Professional and Service Projects (called the Division of Women's and Professional Projects in 1937), which was responsible for white-collar projects including education programs, recreation programs, and the arts projects. It was later named the Division of Community Service Programs and the Service Division.

* The Division of Finance.

* The Division of Information.

* The Division of Investigation, which succeeded a comparable division at FERA and investigated fraud, misappropriation of funds and disloyalty.

* The Division of Statistics, also known as the Division of Social Research.

* The Project Control Division, which processed project applications.

* Other divisions including the Employment, Management, Safety, Supply, and Training and Reemployment.

Employment

The goal of the WPA was to employ most of the unemployed people on relief until the economy recovered.

The goal of the WPA was to employ most of the unemployed people on relief until the economy recovered. Harry Hopkins

Harold Lloyd Hopkins (August 17, 1890 – January 29, 1946) was an American statesman, public administrator, and presidential advisor. A trusted deputy to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Hopkins directed New Deal relief programs before ser ...

testified to Congress in January 1935 why he set the number at 3.5 million, using Federal Emergency Relief Administration

The Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) was a program established by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1933, building on the Hoover administration's Emergency Relief and Construction Act. It was replaced in 1935 by the Works Progre ...

data. Estimating costs at $1,200 per worker per year (), he asked for and received $4 billion (equivalent to $ billion in ). Many women were employed, but they were few compared to men.

In 1935 there were 20 million people on relief in the United States. Of these, 8.3 million were children under 16 years of age; 3.8 million were persons between the ages of 16 and 65 who were not working or seeking work. These included housewives, students in school, and incapacitated persons. Another 750,000 were person age 65 or over. Thus, of the total of 20 million persons then receiving relief, 13 million were not considered eligible for employment. This left a total of 7 million presumably employable persons between the ages of 16 and 65 inclusive. Of these, however, 1.65 million were said to be farm operators or persons who had some non-relief employment, while another 350,000 were, despite the fact that they were already employed or seeking work, considered incapacitated. Deducting this 2 million from the total of 7.15 million, there remained 5.15 million persons age 16 to 65, unemployed, looking for work, and able to work.

Because of the assumption that only one worker per family would be permitted to work under the proposed program, this total of 5.15 million was further reduced by 1.6 million—the estimated number of workers who were members of families with two or more employable people. Thus, there remained a net total of 3.55 million workers in as many households for whom jobs were to be provided.

The WPA reached its peak employment of 3,334,594 people in November 1938. To be eligible for WPA employment, an individual had to be an American citizen, 18 or older, able-bodied, unemployed, and certified as in need by a local public relief agency approved by the WPA. The WPA Division of Employment selected the worker's placement to WPA projects based on previous experience or training. Worker pay was based on three factors: the region of the country, the degree of

Because of the assumption that only one worker per family would be permitted to work under the proposed program, this total of 5.15 million was further reduced by 1.6 million—the estimated number of workers who were members of families with two or more employable people. Thus, there remained a net total of 3.55 million workers in as many households for whom jobs were to be provided.

The WPA reached its peak employment of 3,334,594 people in November 1938. To be eligible for WPA employment, an individual had to be an American citizen, 18 or older, able-bodied, unemployed, and certified as in need by a local public relief agency approved by the WPA. The WPA Division of Employment selected the worker's placement to WPA projects based on previous experience or training. Worker pay was based on three factors: the region of the country, the degree of urbanization

Urbanization (or urbanisation in British English) is the population shift from Rural area, rural to urban areas, the corresponding decrease in the proportion of people living in rural areas, and the ways in which societies adapt to this change. ...

, and the individual's skill

A skill is the learned or innate

ability to act with determined results with good execution often within a given amount of time, energy, or both.

Skills can often be divided into domain-general and domain-specific skills. Some examples of gen ...

. It varied from $19 per month to $94 per month, with the average wage being about $52.50 (). The goal was to pay the local prevailing wage, but limit the hours of work to 8 hours a day or 40 hours a week; the stated minimum being 30 hours a week, or 120 hours a month.

Being a voter or a Democrat was not a prerequisite for a relief job. Federal law specifically prohibited any political discrimination against WPA workers. Vague charges were bandied about at the time. The consensus of experts is that: "In the distribution of WPA project jobs as opposed to those of a supervisory and administrative nature politics plays only a minor in comparatively insignificant role." However those who were hired were reminded at election time that FDR created their job and the Republicans would take it away. The great majority voted accordingly.

Projects

WPA projects were administered by the Division of Engineering and Construction and the Division of Professional and Service Projects. Most projects were initiated, planned and sponsored by states, counties or cities. Nationwide projects were sponsored until 1939. The WPA built traditional infrastructure of theNew Deal

The New Deal was a series of wide-reaching economic, social, and political reforms enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1938, in response to the Great Depression in the United States, Great Depressi ...

such as roads, bridges, schools, libraries, courthouses, hospitals, sidewalks, waterworks, and post-offices, but also constructed museums, swimming pools, parks, community centers, playgrounds, coliseums, markets, fairgrounds, tennis courts, zoos, botanical gardens, auditoriums, waterfronts, city halls, gyms, and university unions. Most of these are still in use today. The amount of infrastructure projects of the WPA included 40,000 new and 85,000 improved buildings. These new buildings included 5,900 new schools; 9,300 new auditoriums, gyms, and recreational buildings; 1,000 new libraries; 7,000 new dormitories; and 900 new armories. In addition, infrastructure projects included 2,302 stadiums, grandstands, and bleachers; 52 fairgrounds and rodeo grounds; 1,686 parks covering 75,152 acres; 3,185 playgrounds; 3,026 athletic fields; 805 swimming pools; 1,817 handball courts; 10,070 tennis courts; 2,261 horseshoe pits; 1,101 ice-skating areas; 138 outdoor theatres; 254 golf courses; and 65 ski jumps. Total expenditures on WPA projects through June 1941 totaled approximately $11.4 billion—the equivalent of $ billion in . Over $4 billion was spent on highway, road, and street projects; more than $1 billion on public buildings, including the Dock Street Theatre in Charleston, the Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles, and Timberline Lodge in Oregon's Mount Hood National Forest.

More than $1 billion—$ in —was spent on publicly owned or operated utilities; and another $1 billion on welfare projects, including sewing projects for women, the distribution of surplus commodities, and school lunch projects. One construction project was the Merritt Parkway in Connecticut, the bridges of which were each designed as architecturally unique. In its eight-year run, the WPA built 325 firehouses and renovated 2,384 of them across the United States. The of water mains, installed by their hand as well, contributed to increased fire protection across the country.

The direct focus of the WPA projects changed with need. In 1935 priority projects were to improve infrastructure; roads, extension of electricity to rural areas, water conservation, sanitation and flood control. In 1936, as outlined in that year's Emergency Relief Appropriations Act, public facilities became a focus; parks and associated facilities, public buildings, utilities, airports, and transportation projects were funded. The following year saw the introduction of agricultural improvements, such as the production of marl fertilizer and the eradication of fungus pests. As the Second World War approached, and then eventually began, WPA projects became increasingly defense related.

One project of the WPA was funding state-level library service demonstration projects, to create new areas of library service to underserved populations and to extend rural service. Another project was the Household Service Demonstration Project, which trained 30,000 women for domestic employment. South Carolina

South Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders North Carolina to the north and northeast, the Atlantic Ocean to the southeast, and Georgia (U.S. state), Georg ...

had one of the larger statewide library service demonstration projects. At the end of the project in 1943, South Carolina had twelve publicly funded county libraries, one regional library, and a funded state library agency.

Federal Project Number One

A significant aspect of the Works Progress Administration was the Federal Project Number One, which had five different parts: the Federal Art Project, the Federal Music Project, the Federal Theatre Project, theFederal Writers' Project

The Federal Writers' Project (FWP) was a federal government project in the United States created to provide jobs for out-of-work writers and to develop a history and overview of the United States, by state, cities and other jurisdictions. It was ...

, and the Historical Records Survey. The government wanted to provide new federal cultural support instead of just providing direct grants to private institutions. After only one year, over 40,000 artists and other talented workers had been employed through this project in the United States. Cedric Larson stated that "The impact made by the five major cultural projects of the WPA upon the national consciousness is probably greater in total than anyone readily realizes. As channels of communication between the administration and the country at large, both directly and indirectly, the importance of these projects cannot be overestimated, for they all carry a tremendous appeal to the eye, the ear, or the intellect—or all three."

Federal Art Project

This project was directed by Holger Cahill, and in 1936 employment peaked at over 5,300 artists. The Arts Service Division created illustrations and posters for the WPA writers, musicians, and theaters. The Exhibition Division had public exhibitions of artwork from the WPA, and artists from the Art Teaching Division were employed in settlement houses and community centers to give classes to an estimated 50,000 children and adults. They set up over 100 art centers around the country that served an estimated eight million individuals.Federal Music Project

Directed by Nikolai Sokoloff, former principal conductor of the Cleveland Orchestra, the Federal Music Project employed over 16,000 musicians at its peak. Its purpose was to create jobs for unemployed musicians, It established new ensembles such as chamber groups, orchestras, choral units, opera units, concert bands, military bands, dance bands, and theater orchestras. They gave 131,000 performances and programs to 92 million people each week. The Federal Music Project performed plays and dances, as well as radio dramas. In addition, the Federal Music Project gave music classes to an estimated 132,000 children and adults every week, recorded folk music, served as copyists, arrangers, and librarians to expand the availability of music, and experimented in music therapy. Sokoloff stated, "Music can serve no useful purpose unless it is heard, but these totals on the listeners' side are more eloquent than statistics as they show that in this country there is a great hunger and eagerness for music."

Directed by Nikolai Sokoloff, former principal conductor of the Cleveland Orchestra, the Federal Music Project employed over 16,000 musicians at its peak. Its purpose was to create jobs for unemployed musicians, It established new ensembles such as chamber groups, orchestras, choral units, opera units, concert bands, military bands, dance bands, and theater orchestras. They gave 131,000 performances and programs to 92 million people each week. The Federal Music Project performed plays and dances, as well as radio dramas. In addition, the Federal Music Project gave music classes to an estimated 132,000 children and adults every week, recorded folk music, served as copyists, arrangers, and librarians to expand the availability of music, and experimented in music therapy. Sokoloff stated, "Music can serve no useful purpose unless it is heard, but these totals on the listeners' side are more eloquent than statistics as they show that in this country there is a great hunger and eagerness for music."

Federal Theatre Project

In 1929, Broadway alone had employed upwards of 25,000 workers, onstage and backstage; in 1933, only 4,000 still had jobs. The Actors' Dinner Club and the Actors' Betterment Association were giving out free meals every day. Every theatrical district in the country suffered as audiences dwindled. The New Deal project was directed by playwrightHallie Flanagan

Hallie Flanagan Davis (August 27, 1889 – June 23, 1969) was an American theatrical producer and director, playwright, and author, best known as director of the Federal Theatre Project, a part of the Works Progress Administration (WPA).

B ...

, and employed 12,700 performers and staff at its peak. They presented more than 1,000 performances each month to almost one million people, produced 1,200 plays in the four years it was established, and introduced 100 new playwrights. Many performers later became successful in Hollywood including Orson Welles

George Orson Welles (May 6, 1915 – October 10, 1985) was an American director, actor, writer, producer, and magician who is remembered for his innovative work in film, radio, and theatre. He is among the greatest and most influential film ...

, John Houseman, Burt Lancaster

Burton Stephen Lancaster (November 2, 1913 – October 20, 1994) was an American actor. Initially known for playing tough characters with tender hearts, he went on to achieve success with more complex and challenging roles over a 45-year caree ...

, Joseph Cotten, Canada Lee, Will Geer, Joseph Losey

Joseph Walton Losey III (; January 14, 1909 – June 22, 1984) was an American film and theatre director, producer, and screenwriter. Born in Wisconsin, he studied in Germany with Bertolt Brecht and then returned to the United States. Hollywood ...

, Virgil Thomson, Nicholas Ray, E.G. Marshall and Sidney Lumet

Sidney Arthur Lumet ( ; June 25, 1924 – April 9, 2011) was an American film director. Lumet started his career in theatre before moving to film, where he gained a reputation for making realistic and gritty New York City, New York dramas w ...

. The Federal Theatre Project was the first project to end; it was terminated in June 1939 after Congress zeroed out the funding.

Federal Writers' Project

This project was directed by Henry Alsberg and employed 6,686 writers at its peak in 1936. The FWP created theAmerican Guide Series

The American Guide Series includes books and pamphlets published from 1937 to 1941 under the auspices of the Federal Writers' Project (FWP), a Great Depression, Depression-era program that was part of the larger Works Progress Administration in the ...

which, when completed, consisted of 378 books and pamphlets providing a thorough analysis of the history, social life and culture for every state, city and village in the United States including descriptions of towns, waterways, historic sites, oral histories, photographs, and artwork. An association or group that put up the cost of publication sponsored each book, the cost was anywhere from $5,000 to $10,000. In almost all cases, the book sales were able to reimburse their sponsors. Additionally, another important part of this project was to record oral histories to create archives such as the Slave Narratives and collections of folklore. These writers also participated in research and editorial services to other government agencies.

Historical Records Survey

This project was the smallest of Federal Project Number One and served to identify, collect, and conserve United States' historical records. It is one of the biggest bibliographical efforts and was directed by Luther H. Evans. At its peak, this project employed more than 4,400 workers.Library Services Program

Before the Great Depression, it was estimated that one-third of the population in the United States did not have reasonable access to public library services. Understanding the need, not only to maintain existing facilities but to expand library services, led to the establishment of the WPA's Library Projects. With the onset of the Depression, local governments facing declining revenues were unable to maintain social services, including libraries. This lack of revenue exacerbated problems of library access that were already widespread. In 1934, only two states, Massachusetts and Delaware, provided their total population access to public libraries. In many rural areas, there were no libraries, and where they did exist, reading opportunities were minimal. Sixty-six percent of the South's population did not have access to any public library. Libraries that existed circulated one book per capita. The early emphasis of these programs was on extending library services to rural populations, by creating libraries in areas that lacked facilities. The WPA library program also greatly augmented reader services in metropolitan and urban centers. By 1938, the WPA Library Services Project had established 2,300 new libraries, 3,400 reading rooms in existing libraries, and 53 traveling libraries for sparsely settled areas. Federal money for these projects could only be spent on worker wages, therefore local municipalities would have to provide upkeep on properties and purchase equipment and materials. At the local level, WPA libraries relied on funding from county or city officials or funds raised by local community organizations such as women's clubs. Due to limited funding, many WPA libraries were "little more than book distribution stations: tables of materials under temporary tents, a tenant home to which nearby readers came for their books, a school superintendents' home, or a crossroads general store." The public response to the WPA libraries was extremely positive. For many, "the WPA had become 'the breadline of the spirit.'" At its height in 1938, there were 38,324 people, primarily women, employed in library services programs, while 25,625 were employed in library services and 12,696 were employed in bookbinding and repair. Because book repair was an activity that could be taught to unskilled workers and once trained, could be conducted with little supervision, repair and mending became the main activity of the WPA Library Project. The basic rationale for this change was that the mending and repair projects saved public libraries and school libraries thousands of dollars in acquisition costs while employing needy women who were often heads of households. By 1940, the WPA Library Project, now the Library Services Program, began to shift its focus as the entire WPA began to move operations towards goals of national defense. WPA Library Programs served those goals in two ways: 1.) existing WPA libraries could distribute materials to the public on the nature of an imminent national defense emergency and the need for national defense preparation, and 2.) the project could provide supplementary library services to military camps and defense impacted communities. By December 1941, the number of people employed in WPA library work was only 16,717. In May of the following year, all statewide Library Projects were reorganized as WPA War Information Services Programs. By early 1943, the work of closing war information centers had begun. The last week of service for remaining WPA library workers was March 15, 1943. While it is difficult to quantify the success or failure of WPA Library Projects relative to other WPA programs, "what is incontestable is the fact that the library projects provided much-needed employment for mostly female workers, recruited many to librarianship in at least semiprofessional jobs, and retained librarians who may have left the profession for other work had employment not come through federal relief...the WPA subsidized several new ventures in readership services such as the widespread use of bookmobiles and supervised reading roomsservices that became permanent in post-depression and postwar American libraries." In extending library services to people who lost their libraries (or never had a library to begin with), WPA Library Services Projects achieved phenomenal success, made significant permanent gains, and had a profound impact on library life in America.Incarceration of Japanese Americans in internment camps

The WPA spent $4.47 million on removal andinternment

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without Criminal charge, charges or Indictment, intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects ...

between March and November 1942, slightly more than the $4.43 million spent by the Army for that purpose during that period. Jason Scott Smith observes that "the eagerness of many WPA administrators to place their organization in the forefront of this wartime enterprise is striking." The WPA was on the ground helping with removal and relocation even before the creation of the WRA. On March 11, Rex L. Nicholson, the WPA's regional director, took charge of the "Reception and Induction" centers that controlled the first thirteen assembly centers. Nicholson's old WPA associates played key roles in the administration of the camps.

WPA veterans involved in internment included Clayton E. Triggs, the first manager of the Manzanar Relocation Center in California, a facility that, according to one insider, was "manned just about 100% by the WPA." Drawing on experiences derived from New Deal–era road building, he supervised the installation of such features as guard towers and spotlights. Then-Secretary of Commerce Harry Hopkins

Harold Lloyd Hopkins (August 17, 1890 – January 29, 1946) was an American statesman, public administrator, and presidential advisor. A trusted deputy to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Hopkins directed New Deal relief programs before ser ...

praised his successor as WPA administrator, Howard O. Hunter, for the "building of those camps for the War Department for the Japanese evacuees on the West Coast."

African Americans

The share ofFederal Emergency Relief Administration

The Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) was a program established by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1933, building on the Hoover administration's Emergency Relief and Construction Act. It was replaced in 1935 by the Works Progre ...

and WPA benefits for African Americans exceeded their proportion of the general population. The FERA's first relief census reported that more than two million African Americans were on relief during early 1933, a proportion of the African-American population (17.8%) that was nearly double the proportion of white Americans on relief (9.5%).John Salmond, "The New Deal and the Negro" in John Braeman et al., eds. ''The New Deal: The National Level'' (1975). pp 188–89 This was during the period of Jim Crow

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws introduced in the Southern United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries that enforced racial segregation, " Jim Crow" being a pejorative term for an African American. The last of the ...

and racial segregation

Racial segregation is the separation of people into race (human classification), racial or other Ethnicity, ethnic groups in daily life. Segregation can involve the spatial separation of the races, and mandatory use of different institutions, ...

in the South, when black Americans were largely disenfranchised.

By 1935, there were 3,500,000 African Americans (men, women and children) on relief, almost 35 percent of the African-American population; plus another 250,000 African-American adults were working on WPA projects. Altogether during 1938, about 45 percent of the nation's African-American families were either on relief or were employed by the WPA.

Civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' political freedom, freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and ...

leaders initially objected that African Americans were proportionally underrepresented. African American leaders made such a claim with respect to WPA hires in New Jersey, stating, "In spite of the fact that Blacks indubitably constitute more than 20 percent of the State's unemployed, they composed 15.9% of those assigned to W.P.A. jobs during 1937." Nationwide in 1940, 9.8% of the population were African American.

However, by 1941, the perception of discrimination against African Americans had changed to the point that the NAACP

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is an American civil rights organization formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E. B. Du&nbs ...

magazine ''Opportunity'' hailed the WPA:

It is to the eternal credit of the administrative officers of the WPA that discrimination on various projects because of race has been kept to a minimum and that in almost every community Negroes have been given a chance to participate in the work program. In the South, as might have been expected, this participation has been limited, and differential wages on the basis of race have been more or less effectively established; but in the northern communities, particularly in the urban centers, the Negro has been afforded his first real opportunity for employment in white-collar occupations.The WPA mostly operated segregated units, as did its youth affiliate, the

National Youth Administration

The National Youth Administration (NYA) was a New Deal agency sponsored by Presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt, Franklin D. Roosevelt during his presidency. It focused on providing work and education for Americans between the ages of 16 and 25. ...

. Blacks were hired by the WPA as supervisors in the North; however of 10,000 WPA supervisors in the South, only 11 were black. Historian Anthony Badger argues, "New Deal programs in the South routinely discriminated against blacks and perpetuated segregation."

People with physical disabilities

The League of the Physically Handicapped in New York was organized in May 1935 to end discrimination by the WPA against the physically disabled unemployed. The city's Home Relief Bureau coded applications by the physically disabled applicants as "PH" ("physically handicapped"). Thus they were not hired by the WPA. In protest, the League held two sit-ins in 1935. The WPA relented and created 1,500 jobs for physically disabled workers in New York City.Women

About 15% of the household heads on relief were women, and youth programs were operated separately by the

About 15% of the household heads on relief were women, and youth programs were operated separately by the National Youth Administration

The National Youth Administration (NYA) was a New Deal agency sponsored by Presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt, Franklin D. Roosevelt during his presidency. It focused on providing work and education for Americans between the ages of 16 and 25. ...

. The average worker was about 40 years old (about the same as the average family head on relief).

WPA policies were consistent with the strong belief of the time that husbands and wives should not both be working (because the second person working would take one job away from some other breadwinner). A study of 2,000 female workers in Philadelphia showed that 90% were married, but wives were reported as living with their husbands in only 18 percent of the cases. Only 2 percent of the husbands had private employment. Of the 2,000 women, all were responsible for one to five additional people in the household.

In rural Missouri, 60% of the WPA-employed women were without husbands (12% were single; 25% widowed; and 23% divorced, separated or deserted). Thus, only 40% were married and living with their husbands, but 59% of the husbands were permanently disabled, 17% were temporarily disabled, 13% were too old to work, and remaining 10% were either unemployed or disabled. Most of the women worked with sewing projects, where they were taught to use sewing machines and made clothing and bedding, as well as supplies for hospitals, orphanages, and adoption centers.

One WPA-funded project, the Pack Horse Library Project, mainly employed women to deliver books to rural areas in eastern Kentucky. Many of the women employed by the project were the sole breadwinners for their families.

Criticism

The WPA had numerous critics. The strongest attacks were that it was the prelude for a national political machine on behalf of Roosevelt. Reformers secured the Hatch Act of 1939 that largely depoliticized the WPA.

Others complained that far left elements played a major role, especially in the New York City unit. Representative J. Parnell Thomas of the House Committee on Un-American Activities claimed in 1938 that divisions of the WPA were a "hotbed of Communists" and "one more link in the vast and unparalleled New Deal propaganda network."

Much of the criticism of the distribution of projects and funding allotment is a result of the view that the decisions were politically motivated. The South, despite being the poorest region of the United States, received 75% less in federal relief and public works funds per capita than the West. Critics would point to the fact that Roosevelt's Democrats could be sure of voting support from the South, whereas the West was less of a sure thing;

The WPA had numerous critics. The strongest attacks were that it was the prelude for a national political machine on behalf of Roosevelt. Reformers secured the Hatch Act of 1939 that largely depoliticized the WPA.

Others complained that far left elements played a major role, especially in the New York City unit. Representative J. Parnell Thomas of the House Committee on Un-American Activities claimed in 1938 that divisions of the WPA were a "hotbed of Communists" and "one more link in the vast and unparalleled New Deal propaganda network."

Much of the criticism of the distribution of projects and funding allotment is a result of the view that the decisions were politically motivated. The South, despite being the poorest region of the United States, received 75% less in federal relief and public works funds per capita than the West. Critics would point to the fact that Roosevelt's Democrats could be sure of voting support from the South, whereas the West was less of a sure thing; swing state

In United States politics, a swing state (also known as battleground state, toss-up state, or purple state) is any state that could reasonably be won by either the Democratic or Republican candidate in a statewide election, most often refe ...

s took priority over the other states.

There was a perception that WPA employees were not diligent workers, and that they had little incentive to give up their busy work

Busy work (also known as make-work and busywork) is an activity that is undertaken to pass time and stay busy but in and of itself has little or no actual value. Busy work occurs in business, military and other settings, in situations where peop ...

in favor of productive jobs. Some employers said that the WPA instilled poor work habits and encouraged inefficiency. Some job applicants found that a WPA work history was viewed negatively by employers, who said they had formed poor work habits.

A Senate committee reported that, "To some extent the complaint that WPA workers do poor work is not without foundation. ... Poor work habits and incorrect techniques are not remedied. Occasionally a supervisor or a foreman demands good work." The WPA and its workers were ridiculed as being lazy. The organization's initials were said to stand for "We Poke Along" or "We Putter Along" or "We Piddle Around" or "Whistle, Piss and Argue." These were sarcastic references to WPA projects that sometimes slowed down deliberately because foremen had an incentive to keep going, rather than finish a project.

The WPA's Division of Investigation proved so effective in preventing political corruption "that a later congressional investigation couldn't find a single serious irregularity it had overlooked," wrote economist Paul Krugman

Paul Robin Krugman ( ; born February 28, 1953) is an American New Keynesian economics, New Keynesian economist who is the Distinguished Professor of Economics at the CUNY Graduate Center, Graduate Center of the City University of New York. He ...

. "This dedication to honest government wasn't a sign of Roosevelt's personal virtue; rather, it reflected a political imperative. FDR's mission in office was to show that government activism works. To maintain that mission's credibility he needed to keep his administration's record clean. And he did."

Many complaints were recorded from private industry at the time that the existence of WPA works programs made hiring new workers difficult. The WPA claimed to counter this by keeping hourly wages well below private wages and encouraging relief workers to actively seek private employment and accept job offers if they got them.

Evolution

On December 23, 1938, after leading the WPA for three and a half years,

On December 23, 1938, after leading the WPA for three and a half years, Harry Hopkins

Harold Lloyd Hopkins (August 17, 1890 – January 29, 1946) was an American statesman, public administrator, and presidential advisor. A trusted deputy to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Hopkins directed New Deal relief programs before ser ...

resigned and became the Secretary of Commerce

The United States secretary of commerce (SecCom) is the head of the United States Department of Commerce. The secretary serves as the principal advisor to the president of the United States on all matters relating to commerce. The secretary rep ...

. To succeed him Roosevelt appointed Francis C. Harrington, a colonel in the Army Corps of Engineers and the WPA's chief engineer, who had been leading the Division of Engineering and Construction.

Following the passage of the Reorganization Act of 1939

The Reorganization Act of 1939, , is an American Act of Congress which gave the President of the United States the authority to hire additional confidential staff and reorganize the executive branch (within certain limits) for two years subject ...

in April 1939, the WPA was grouped with the Bureau of Public Roads

The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) is a division of the United States Department of Transportation that specializes in highway transportation. The agency's major activities are grouped into two programs, the Federal-aid Highway Program a ...

, Public Buildings Branch of the Procurement Division, Branch of Buildings Management of the National Park Service

The National Park Service (NPS) is an List of federal agencies in the United States, agency of the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government, within the US Department of the Interior. The service manages all List ...

, United States Housing Authority

The United States Housing Authority, or USHA, was a Alphabet agencies, federal agency created during 1937 within the United States Department of the Interior by the Housing Act of 1937 as part of the New Deal.

It was designed to lend money to the ...

and the Public Works Administration

The Public Works Administration (PWA), part of the New Deal of 1933, was a large-scale public works construction agency in the United States headed by United States Secretary of the Interior, Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes. It was ...

under the newly created Federal Works Agency. Created at the same time, the Federal Security Agency

The Federal Security Agency (FSA) was an Independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the United States government established in 1939 pursuant to the Reorganization Act of 1939. For a time, the agency oversaw food ...

assumed the WPA's responsibility for the National Youth Administration

The National Youth Administration (NYA) was a New Deal agency sponsored by Presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt, Franklin D. Roosevelt during his presidency. It focused on providing work and education for Americans between the ages of 16 and 25. ...

. "The name of the Works Progress Administration has been changed to Work Projects Administration in order to make its title more descriptive of its major purpose," President Roosevelt wrote when announcing the reorganization.

As WPA projects became more subject to the state, local sponsors were called on to provide 25% of project costs. As the number of public works projects slowly diminished, more projects were dedicated to preparing for war. Having languished since the end of World War I, the American military services were depopulated and served by crumbling facilities; when Germany occupied Czechoslovakia in 1938, the U.S. Army numbered only 176,000 soldiers.

On May 26, 1940, FDR delivered a fireside chat to the American people about "the approaching storm", and on June 6 Harrington reprioritized WPA projects, anticipating a major expansion of the U.S. military. "Types of WPA work to be expedited in every possible way to include, in addition to airports and military airfields, construction of housing and other facilities for enlarged military garrisons, camp and cantonment construction, and various improvements in navy yards," Harrington said. He observed that the WPA had already made substantial contributions to national defense over its five years of existence, by building 85 percent of the new airports in the U.S. and making $420 million in improvements to military facilities. He predicted there would be 500,000 WPA workers on defense-related projects over the next 12 months, at a cost of $250 million. The estimated number of WPA workers needed for defense projects was soon revised to between 600,000 and 700,000. Vocational training for war industries was also begun by the WPA, with 50,000 trainees in the program by October 1940.

"Only the WPA, having employed millions of relief workers for more than five years, had a comprehensive awareness of the skills that would be available in a full-scale national emergency," wrote journalist Nick Taylor. "As the country began its preparedness buildup, the WPA was uniquely positioned to become a major defense agency."

Harrington died suddenly, aged 53, on September 30, 1940. Notably apolitical—he boasted that he had never voted—he had deflected Congressional criticism of the WPA by bringing attention to its building accomplishments and its role as an employer. Harrington's successor, Howard O. Hunter, served as head of the WPA until May 1, 1942.

On May 26, 1940, FDR delivered a fireside chat to the American people about "the approaching storm", and on June 6 Harrington reprioritized WPA projects, anticipating a major expansion of the U.S. military. "Types of WPA work to be expedited in every possible way to include, in addition to airports and military airfields, construction of housing and other facilities for enlarged military garrisons, camp and cantonment construction, and various improvements in navy yards," Harrington said. He observed that the WPA had already made substantial contributions to national defense over its five years of existence, by building 85 percent of the new airports in the U.S. and making $420 million in improvements to military facilities. He predicted there would be 500,000 WPA workers on defense-related projects over the next 12 months, at a cost of $250 million. The estimated number of WPA workers needed for defense projects was soon revised to between 600,000 and 700,000. Vocational training for war industries was also begun by the WPA, with 50,000 trainees in the program by October 1940.

"Only the WPA, having employed millions of relief workers for more than five years, had a comprehensive awareness of the skills that would be available in a full-scale national emergency," wrote journalist Nick Taylor. "As the country began its preparedness buildup, the WPA was uniquely positioned to become a major defense agency."

Harrington died suddenly, aged 53, on September 30, 1940. Notably apolitical—he boasted that he had never voted—he had deflected Congressional criticism of the WPA by bringing attention to its building accomplishments and its role as an employer. Harrington's successor, Howard O. Hunter, served as head of the WPA until May 1, 1942.

Termination

Unemployment ended with war production forWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, as millions of men joined the services, and cost-plus contracts made it attractive for companies to hire unemployed men and train them.

Concluding that a national relief program was no longer needed, Roosevelt directed the Federal Works Administrator to end the WPA in a letter December 4, 1942. "Seven years ago I was convinced that providing useful work is superior to any and every kind of dole. Experience had amply justified this policy," FDR wrote:

By building airports, schools, highways, and parks; by making huge quantities of clothing for the unfortunate; by serving millions of lunches to school children; by almost immeasurable kinds and quantities of service the Work Projects Administration has reached a creative hand into every county in this Nation. It has added to the national wealth, has repaired the wastage of depression, and has strengthened the country to bear the burden of war. By employing eight millions of Americans, with thirty millions of dependents, it has brought to these people renewed hope and courage. It has maintained and increased their working skills; and it has enabled them once more to take their rightful places in public or in private employment.Roosevelt ordered a prompt end to WPA activities to conserve funds that had been appropriated. Operations in most states ended February 1, 1943. With no funds budgeted for the next fiscal year, the WPA ceased to exist after June 30, 1943.

Legacy

"The agencies of the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration had an enormous and largely unrecognized role in defining the public space we now use", wrote sociologist Robert D. Leighninger. "In a short period of ten years, thePublic Works Administration

The Public Works Administration (PWA), part of the New Deal of 1933, was a large-scale public works construction agency in the United States headed by United States Secretary of the Interior, Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes. It was ...

, the Works Progress Administration, and the Civilian Conservation Corps

The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) was a voluntary government unemployment, work relief program that ran from 1933 to 1942 in the United States for unemployed, unmarried men ages 18–25 and eventually expanded to ages 17–28. The CCC was ...

built facilities in practically every community in the country. Most are still providing service half a century later. It is time we recognized this legacy and attempted to comprehend its relationship to our contemporary situation."

Guntersville, Alabama

Guntersville (previously known as Gunter's Ferry and later Gunter's Landing) is a city and the county seat of Marshall County, Alabama, United States. At the 2020 census, the population of the city was 8,553. Guntersville is located in a HUB ...

(1936)

File:Prairie County Courthouse, De Valls Bluff, AR 001.jpg, Prairie County Courthouse, DeValls Bluff, Arkansas (1939)

File:Griffith observatory 2006.jpg, Griffith Observatory, Los Angeles

Los Angeles, often referred to by its initials L.A., is the List of municipalities in California, most populous city in the U.S. state of California, and the commercial, Financial District, Los Angeles, financial, and Culture of Los Angeles, ...

, California

California () is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States that lies on the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. It borders Oregon to the north, Nevada and Arizona to the east, and shares Mexico–United States border, an ...

(1933)

File:Santa Ana City Hall.jpg, Santa Ana City Hall, Santa Ana, California

Santa Ana (Spanish language, Spanish for ) is a city in and the county seat of Orange County, California, United States. Located in the Greater Los Angeles region of Southern California, the city's population was 310,227 at the 2020 census. As ...

(1935)

File:08-06-18LeonHighSchl1.JPG, Leon High School, Tallahassee, Florida

Tallahassee ( ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the U.S. state of Florida. It is the county seat of and the only incorporated municipality in Leon County, Florida, Leon County. Tallahassee became the capital of Fl ...

(1936–37)

File:St Aug Govt House Museum01.jpg, Government House, St. Augustine, Florida (1937)

File:Fort Hawkins Macon, Georgia.jpg, Fort Hawkins, Macon, Georgia

Macon ( ), officially Macon–Bibb County, is a consolidated city-county in Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia, United States. Situated near the Atlantic Seaboard fall line, fall line of the Ocmulgee River, it is southeast of Atlanta and near the ...

(1936–1938)

File:Boise High School Gymnasium.jpg, Boise High School Gymnasium, Boise, Idaho

Boise ( ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of cities in Idaho, most populous city of the U.S. state of Idaho. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, there were 235,685 people residing in the city. Loca ...

(1936)

File:Midway Airport Airfield.jpg, Midway International Airport

Chicago Midway International Airport is a major commercial airport on the southwest side of Chicago, Illinois, located approximately 12 miles (19 km) from the city's Loop business district, and divided between the city's Clearing and ...

, Chicago

Chicago is the List of municipalities in Illinois, most populous city in the U.S. state of Illinois and in the Midwestern United States. With a population of 2,746,388, as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is the List of Unite ...

, Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. It borders on Lake Michigan to its northeast, the Mississippi River to its west, and the Wabash River, Wabash and Ohio River, Ohio rivers to its ...

(1935–1939)

File:Bandshell in Gregg Park.jpg, Gregg Park Bandshell, Vincennes, Indiana (1939)

File:WPA canoe house iowa.jpg, Canoe house, University of Iowa

The University of Iowa (U of I, UIowa, or Iowa) is a public university, public research university in Iowa City, Iowa, United States. Founded in 1847, it is the oldest and largest university in the state. The University of Iowa is organized int ...

(1937)

File:Jenkins culvert (Gove Co) from NE 1.JPG, Jenkins Culvert, Gove County, Kansas (1938)

File:Louisville Fire Department Headquarters.jpg, Louisville Fire Department Headquarters, Louisville, Kentucky

Louisville is the List of cities in Kentucky, most populous city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky, sixth-most populous city in the Southeastern United States, Southeast, and the list of United States cities by population, 27th-most-populous city ...

(1936)

File:BywaterAlvarNOPL2.jpg, Alvar Street Branch, New Orleans Public Library (1940)

File:WPA Field House.jpg, WPA Field House and Pump Station, Scituate, Massachusetts (1938)

File:Detroit Naval Armory.jpg, Detroit Naval Armory, Detroit

Detroit ( , ) is the List of municipalities in Michigan, most populous city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is situated on the bank of the Detroit River across from Windsor, Ontario. It had a population of 639,111 at the 2020 United State ...

, Michigan

Michigan ( ) is a peninsular U.S. state, state in the Great Lakes region, Great Lakes region of the Upper Midwest, Upper Midwestern United States. It shares water and land boundaries with Minnesota to the northwest, Wisconsin to the west, ...

(1936–1939)

File:Brandon Auditorium & Fire Hall.jpg, Brandon Auditorium and Fire Hall, Brandon, Minnesota

Brandon is a city in Douglas County, Minnesota, United States. The population was 501 at the 2020 census.

History

The village of Brandon was incorporated on November 22, 1881. The current town site was laid out when the railroad was being bu ...

(1936)

File:Milaca City Hall 2.jpg, Milaca Municipal Hall, Milaca, Minnesota

Milaca ( ) is a city and the county seat of Mille Lacs County, Minnesota, Mille Lacs County, Minnesota. The population was 3,021 at the time of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. It is situated on the Rum River.

History

A post office ...

(1936)

File:Upland, Nebraska Prairie Ave 5 auditorium.JPG, Upland Auditorium, Upland, Nebraska (1936)

File:Jackie Robinson Play Center entrance.jpg, Jackie Robinson Play Center, Harlem

Harlem is a neighborhood in Upper Manhattan, New York City. It is bounded roughly by the Hudson River on the west; the Harlem River and 155th Street on the north; Fifth Avenue on the east; and Central Park North on the south. The greater ...

, New York (1936)

File:LaGuardia Airport.JPG, LaGuardia Airport

LaGuardia Airport ( ) – colloquially known as LaGuardia or simply LGA – is a civil airport in East Elmhurst, Queens, East Elmhurst, Queens, New York City, situated on the North Shore (Long Island), northwestern shore of Long Island, bord ...

, Queens

Queens is the largest by area of the Boroughs of New York City, five boroughs of New York City, coextensive with Queens County, in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York. Located near the western end of Long Island, it is bordered by the ...

, New York (1937–1939)

File:Rhinebeck, NY, post office.jpg, U.S. Post Office, Rhinebeck, New York

Rhinebeck is a village (New York), village in the Rhinebeck (town), New York, town of Rhinebeck in Dutchess County, New York, United States. The population was 2,657 at the 2010 census. It is part of the Kiryas Joel–Poughkeepsie–Newburgh metr ...

(1940)

File:Robeson County Ag Bldg from SE 2.JPG, Robeson County Agricultural Building, Lumberton, North Carolina (1937)

File:Emmons County Courthouse 2009.jpg, Emmons County Courthouse, Linton, North Dakota (1934)

File:Rubber Bowl - Akron Ohio.jpg, Rubber Bowl Stadium, Akron, Ohio

Akron () is a city in Summit County, Ohio, United States, and its county seat. It is the List of municipalities in Ohio, fifth-most populous city in Ohio, with a population of 190,469 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. The Akron metr ...

(1940)

File:Timberline-Lodge-Interior-13025.jpg, Timberline Lodge, Mt. Hood National Forest, Oregon

Oregon ( , ) is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. It is a part of the Western U.S., with the Columbia River delineating much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while t ...

(1936–1938)

File:OSLinside.JPG, Oregon State Library, Salem, Oregon

Salem ( ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the U.S. state of Oregon, and the county seat of Marion County, Oregon, Marion County. It is located in the center of the Willamette Valley alongside the Willamette River, w ...

(1939)

File:SchenleyPark Bridge Pittsburgh.jpg, Schenley Park

Schenley Park () is a large municipal park in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, United States. It is located between the neighborhoods of Oakland (Pittsburgh), Oakland, Greenfield (Pittsburgh), Greenfield, and Squirrel Hill. It is also listed on the Nat ...

, Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, United States, and its county seat. It is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania#Municipalities, second-most populous city in Pennsylvania (after Philadelphia) and the List of Un ...

, Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania, officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a U.S. state, state spanning the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern United States, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes region, Great Lakes regions o ...

(1938–39)

File:McCoy Stadium.jpg, McCoy Stadium, Pawtucket, Rhode Island