Winwood Reade on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

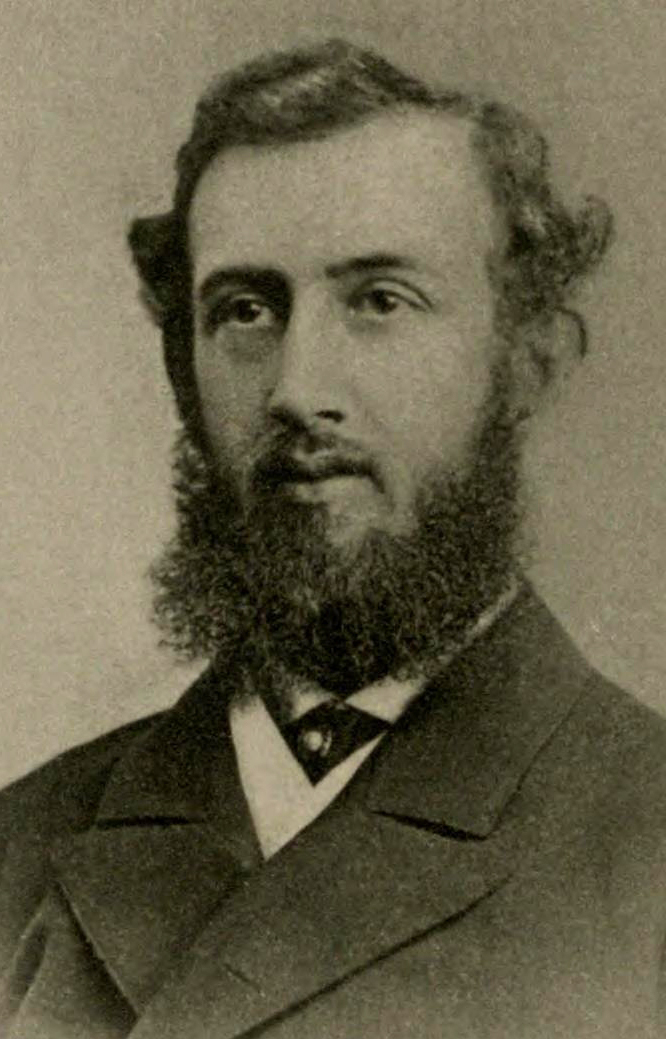

William Winwood Reade (26 December 1838 – 24 April 1875) was a British historian, explorer, novelist and philosopher. His two best-known books, the universal history ''The Martyrdom of Man'' (1872) and the novel ''The Outcast'' (1875), were included in the

William Winwood Reade (26 December 1838 – 24 April 1875) was a British historian, explorer, novelist and philosopher. His two best-known books, the universal history ''The Martyrdom of Man'' (1872) and the novel ''The Outcast'' (1875), were included in the

''Savage Africa''

* (1865). ''See-Saw: A Novel'' (Written under the pseudonym Francesco Abati).Cushing, William (1885). ''Initials and Pseudonyms: A Dictionary of Literary Disguises''. New York : T. Y. Crowell & Co., p. 5. * (1872)

''The Martyrdom of Man''

* (1873)

''African Sketch-Book''

* (1874). ''The Story of the Ashantee Campaign''. * (1875)

''The Outcast''

* (1972). ''Religion in History''.

Works by William Winwood Reade

at

Works by William Winwood Reade

at

Winwood Reade's "The Martyrdom of Man": The Boys' Book of All Knowledge?

Winwood Reade: The Literary Explorer

The active life: the explorer as biographical subject, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

Darwin Correspondence Project

Correspondence between William Winwood Reade and Charles Darwin {{DEFAULTSORT:Reade, William 1838 births 1875 deaths 19th-century British journalists 19th-century Scottish historians British male journalists British people of the Third Anglo-Ashanti War Critics of Christianity Explorers of Africa Freethought writers Scottish war correspondents

William Winwood Reade (26 December 1838 – 24 April 1875) was a British historian, explorer, novelist and philosopher. His two best-known books, the universal history ''The Martyrdom of Man'' (1872) and the novel ''The Outcast'' (1875), were included in the

William Winwood Reade (26 December 1838 – 24 April 1875) was a British historian, explorer, novelist and philosopher. His two best-known books, the universal history ''The Martyrdom of Man'' (1872) and the novel ''The Outcast'' (1875), were included in the Thinker's Library

The Thinker's Library was a series of 140 small hardcover books published between 1929 and 1951 for the Rationalist Press Association by Watts & Co., London, a company founded by the brothers Charles and John Watts.

The series was launched at ...

. Reade published one novel under the pseudonym, Francesco Abati.

Biography

Early life

Born inPerthshire

Perthshire ( locally: ; gd, Siorrachd Pheairt), officially the County of Perth, is a historic county and registration county in central Scotland. Geographically it extends from Strathmore in the east, to the Pass of Drumochter in the nort ...

, Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

, in 1838, William Winwood Reade was a "scion of a wealthy landed family". Having failed at Oxford University

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

and, despite having composed two novels, "failed in any conventional sense as a novelist", Reade decided to begin geographical exploration.

Travels to Africa

Thus, at age 25, using his private funds and with sponsorship from theRoyal Geographical Society

The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers), often shortened to RGS, is a learned society and professional body for geography based in the United Kingdom. Founded in 1830 for the advancement of geographical scien ...

, he departed for Africa, arriving in Cape Town

Cape Town ( af, Kaapstad; , xh, iKapa) is one of South Africa's three capital cities, serving as the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. It is the legislative capital of the country, the oldest city in the country, and the second largest ...

by paddle steamer

A paddle steamer is a steamship or steamboat powered by a steam engine that drives paddle wheels to propel the craft through the water. In antiquity, paddle wheelers followed the development of poles, oars and sails, where the first uses wer ...

during 1862. After several months of observing gorilla

Gorillas are herbivorous, predominantly ground-dwelling great apes that inhabit the tropical forests of equatorial Africa. The genus ''Gorilla'' is divided into two species: the eastern gorilla and the western gorilla, and either four ...

s and travelling through Angola

, national_anthem = "Angola Avante"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capital = Luanda

, religion =

, religion_year = 2020

, religion_ref =

, coordinat ...

, Reade returned home and published his first travel account, ''Savage Africa''. Although criticised for its juvenile style, the book is notable for its anthropological

Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including past human species. Social anthropology studies patterns of be ...

inquiries, as well as for its exculpatory passages concerning the slave trade and its prophecy of an Africa divided between Britain and France in which black Africans have become extinct.

In 1868 Reade secured the patronage of London-based Gold Coast trader Andrew Swanzy to journey to West Africa. After failing to get permission to enter the Ashanti Empire

The Asante Empire (Asante Twi: ), today commonly called the Ashanti Empire, was an Akan state that lasted between 1701 to 1901, in what is now modern-day Ghana. It expanded from the Ashanti Region to include most of Ghana as well as parts of Iv ...

, Reade set out north from Freetown

Freetown is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Sierra Leone. It is a major port city on the Atlantic Ocean and is located in the Western Area of the country. Freetown is Sierra Leone's major urban, economic, financial, cultural, educ ...

to explore the areas past the Solimana capital of Falaba

{{Infobox settlement

, official_name = Falaba

, other_name =

, native_name =

, nickname =

, settlement_type =

, motto =

, image_skyline =

, imagesize ...

. He was detained in Falaba by the local King Seedwa, who imprisoned him for three months under conditions of physical and mental hardship. Legend has it that King Seedwa set four gruelling tasks for Reade each day of his captivity, all of which Reade completed with aplomb.

Though Reade travelled over some unexplored territory, his findings excited little interest among geographers, due mostly to his failure to make accurate measurements of his journey as his sextant

A sextant is a doubly reflecting navigation instrument that measures the angular distance between two visible objects. The primary use of a sextant is to measure the angle between an astronomical object and the horizon for the purposes of ce ...

and other instruments had been left behind at Port Loko

Port Loko is the capital of Port Loko District and since 2017 the North West Province of Sierra Leone. The city had a population of 21,961 in the 2004 census and current estimate of 44,900. Port Loko lies approximately 36 miles north-east of Free ...

. However, his experiences of West Africa were not entirely lost to science, thanks to his correspondence with Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended ...

. Darwin subsequently used information given by Reade for his publication ''The Descent of Man

''The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex'' is a book by English naturalist Charles Darwin, first published in 1871, which applies evolutionary theory to human evolution, and details his theory of sexual selection, a form of biol ...

'' (1871).

Soon after Reade's return, he published his ''The African Sketch-Book'' (1873), an account of his travels that also recommended greater British involvement in West Africa. Reade returned to Africa in 1873 to serve as a correspondent for the Ashanti War

The Anglo-Ashanti wars were a series of five conflicts that took place between 1824 and 1900 between the Ashanti Empire—in the Akan interior of the Gold Coast—and the British Empire and its African allies. Though the Ashanti emerged victori ...

, but died not long after. He was buried in Ipsden

Ipsden is a village and civil parish in the Chiltern Hills in South Oxfordshire, about southeast of Wallingford. It is almost equidistant from Oxford and Reading, Berkshire.

Parish church

The Church of England parish church of Saint Mary th ...

churchyard, Oxfordshire

Oxfordshire is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in the north west of South East England. It is a mainly rural county, with its largest settlement being the city of Oxford. The county is a centre of research and development, primaril ...

, close to the family home.

''The Martyrdom Of Man'' (1872)

''The Martyrdom of Man'' (1872)—- whose summary line reads "From Nebula to Nation"—- is asecular

Secularity, also the secular or secularness (from Latin ''saeculum'', "worldly" or "of a generation"), is the state of being unrelated or neutral in regards to religion. Anything that does not have an explicit reference to religion, either negativ ...

, "universal" history of the Western world. Structurally, it is divided into four "chapters" of approximately 150 pages each: the first chapter, "War", discusses the imprisonment of men's bodies, the second, "Religion", that of their minds, the third, "Liberty", is the closest to a conventional European political and intellectual history, and the fourth, "Intellect", which discusses the cosmogony

Cosmogony is any model concerning the origin of the cosmos or the universe.

Overview

Scientific theories

In astronomy, cosmogony refers to the study of the origin of particular astrophysical objects or systems, and is most commonly used ...

characteristic of a "universal history".

Secularism

According to one historian, the book became a kind of "substitute bible for secularists" in which Reade attempts to trace the development of Western civilisation in terms analogous to those used in the natural sciences. He uses it to advance the philosophy of political liberalism andsocial Darwinism

Social Darwinism refers to various theories and societal practices that purport to apply biological concepts of natural selection and survival of the fittest to sociology, economics and politics, and which were largely defined by scholars in We ...

."Becoming an explorer: The Martyrdom of Winwood Reade" in ''Geography Militant: Cultures of Exploration in the Age of Empire'' by Felix Driver, Blackwell, 1999, 90–116. The final section of the book provoked enormous controversy due to Reade's "outspoken attack on Christian dogma" and the book was condemned by several magazines. In 1872 William Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British statesman and Liberal politician. In a career lasting over 60 years, he served for 12 years as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, spread over four non-conse ...

, the British Prime Minister, denounced ''The Martyrdom of Man'' as one of several "irreligious works" (the others included work by Auguste Comte

Isidore Marie Auguste François Xavier Comte (; 19 January 1798 – 5 September 1857) was a French philosopher and writer who formulated the doctrine of positivism. He is often regarded as the first philosopher of science in the modern sense ...

, Herbert Spencer

Herbert Spencer (27 April 1820 – 8 December 1903) was an English philosopher, psychologist, biologist, anthropologist, and sociologist famous for his hypothesis of social Darwinism. Spencer originated the expression " survival of the f ...

, and David Friedrich Strauss

David Friedrich Strauss (german: link=no, Strauß ; 27 January 1808 – 8 February 1874) was a German liberal Protestant theologian and writer, who influenced Christian Europe with his portrayal of the "historical Jesus", whose divine nature he ...

).

Reade was not an atheist

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the existence of deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there no ...

, as some of his critics maintained; he had a "presumptive belief in a Creator, but one ineffable and unapproachable, far beyond the grasp of the human intellect or the reach of petty human prayers". He was a social Darwinist

Social Darwinism refers to various theories and societal practices that purport to apply biological concepts of natural selection and survival of the fittest to sociology, economics and politics, and which were largely defined by scholars in We ...

who believed in the survival of the fittest

"Survival of the fittest" is a phrase that originated from Darwinian evolutionary theory as a way of describing the mechanism of natural selection. The biological concept of fitness is defined as reproductive success. In Darwinian terms, ...

and wanted to create a new civilisation, contending that "while war, slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

, and religion had once been necessary, they would not always be so; in the future only science could guarantee human progress". Nevertheless, the book "drew attention to the immense tale of suffering and waste involved in the theory of evolution".

Reception and influence

V. S. Pritchett lauded ''The Martyrdom of Man'' as "the one, the outstanding, dramatic, imaginative historical picture of life, to be inspired by Victorian science". Since ''The Martyrdom of Man'' had, by Victorian standards, a relatively sympathetic account of African history, it was approvingly cited by W. E. B. Du Bois in his books ''The Negro'' (1915) and ''The World and Africa'' (1947).Cecil Rhodes

Cecil John Rhodes (5 July 1853 – 26 March 1902) was a British mining magnate and politician in southern Africa who served as Prime Minister of the Cape Colony from 1890 to 1896.

An ardent believer in British imperialism, Rhodes and his Bri ...

, an English-born South African politician and businessman, said that the book "made me what I am". Other admirers of ''The Martyrdom of Man'' included H. G. Wells, Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

,''Loyalists and Loners'' by Michael Foot, Collins, 1986, p. 305-8. Harry Johnston

Sir Henry Hamilton Johnston (12 June 1858 – 31 July 1927), known as Harry Johnston, was a British explorer, botanist, artist, colonial administrator, and linguist who travelled widely in Africa and spoke many African languages. He publishe ...

, George Orwell

Eric Arthur Blair (25 June 1903 – 21 January 1950), better known by his pen name George Orwell, was an English novelist, essayist, journalist, and critic. His work is characterised by lucid prose, social criticism, opposition to totalit ...

, Susan Isaacs

Susan Isaacs (born December 7, 1943) is an American novelist, essayist, and screenwriter. She adapted her debut novel into the film ''Compromising Positions''.

Early life, family and education

She was born in Brooklyn, New York, to Helen Asher ...

, A. A. Milne and his son Christopher Robin

Christopher Robin is a character created by A. A. Milne, based on his son Christopher Robin Milne. The character appears in the author's popular books of poetry and ''Winnie-the-Pooh'' stories, and has subsequently appeared in various Disney ...

, and Michael Foot

Michael Mackintosh Foot (23 July 19133 March 2010) was a British Labour Party politician who served as Labour Leader from 1980 to 1983. Foot began his career as a journalist on ''Tribune'' and the ''Evening Standard''. He co-wrote the 1940 p ...

.

''The Outcast'' (1875)

Reade's other secularist work, ''The Outcast'' (1875), is a short novel about a young man who must deal with being rejected by his religious father and the death of his wife.References in literature

Reade is quoted in one ofArthur Conan Doyle

Sir Arthur Ignatius Conan Doyle (22 May 1859 – 7 July 1930) was a British writer and physician. He created the character Sherlock Holmes in 1887 for ''A Study in Scarlet'', the first of four novels and fifty-six short stories about Ho ...

's Sherlock Holmes

Sherlock Holmes () is a fictional detective created by British author Arthur Conan Doyle. Referring to himself as a " consulting detective" in the stories, Holmes is known for his proficiency with observation, deduction, forensic science and ...

adventures, ''The Sign of the Four

''The Sign of the Four'' (1890), also called ''The Sign of Four'', is the second novel featuring Sherlock Holmes by British writer Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Doyle wrote four novels and 56 short stories featuring the fictional detective.

Plot ...

''. In the second chapter, Holmes recommends ''The Martyrdom of Man'' to Dr. Watson as 'one of the most remarkable ooksever penned.' He remarks subsequently in chapter ten:

"Winwood Reade is good upon the subject," said Holmes. "He remarks that, while the individual man is an insoluble puzzle, in the aggregate he becomes a mathematical certainty. You can, for example, never foretell what any one man will do, but you can say with precision what an average number will be up to. Individuals vary, but percentages remain constant. So says the statistician".

Works

* (1859). ''Charlotte and Myra: A Puzzle in Six Bits''. * (1860). ''Liberty Hall, Oxon. (A Novel)'' * (1861). ''The Veil of Isis or Mysteries of the Druids''. ** ''The Druids''. ** ''Druidism in Rustic Folklore''. ** ''Druidism in the Emblems of Freemasonry''. ** ''Druidism in the Ceremonies of the Church Of Rome''. ** ''Rites And Ceremonies Of The Druids''. ** ''Vestiges Of Druidism''. ** ''The Destruction Of The Druids''. ** ''Priestesses Of The Druids – Pamphlet''. * (1864)''Savage Africa''

* (1865). ''See-Saw: A Novel'' (Written under the pseudonym Francesco Abati).Cushing, William (1885). ''Initials and Pseudonyms: A Dictionary of Literary Disguises''. New York : T. Y. Crowell & Co., p. 5. * (1872)

''The Martyrdom of Man''

* (1873)

''African Sketch-Book''

* (1874). ''The Story of the Ashantee Campaign''. * (1875)

''The Outcast''

* (1972). ''Religion in History''.

References

External links

*Works by William Winwood Reade

at

JSTOR

JSTOR (; short for ''Journal Storage'') is a digital library founded in 1995 in New York City. Originally containing digitized back issues of academic journals, it now encompasses books and other primary sources as well as current issues of j ...

Works by William Winwood Reade

at

Hathi Trust

HathiTrust Digital Library is a large-scale collaborative repository of digital content from research libraries including content digitized via Google Books and the Internet Archive digitization initiatives, as well as content digitized locally ...

*

*Winwood Reade's "The Martyrdom of Man": The Boys' Book of All Knowledge?

Lincoln Allison

Lincoln Allison (born 5 October 1946 in Hartlepool) is an English academic and essayist.

Life and career

Allison grew up in Colne, Lancashire, and was educated at Royal Grammar School, Lancaster, and at University and Nuffield Colleges, Oxford ...

, University of WarwickWinwood Reade: The Literary Explorer

The active life: the explorer as biographical subject, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

Darwin Correspondence Project

Correspondence between William Winwood Reade and Charles Darwin {{DEFAULTSORT:Reade, William 1838 births 1875 deaths 19th-century British journalists 19th-century Scottish historians British male journalists British people of the Third Anglo-Ashanti War Critics of Christianity Explorers of Africa Freethought writers Scottish war correspondents