Wilma P. Mankiller on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Wilma Pearl Mankiller ( chr, ᎠᏥᎳᏍᎩ ᎠᏍᎦᏯᏗᎯ, Atsilasgi Asgayadihi; November 18, 1945April 6, 2010) was a Native American ( Cherokee Nation) activist, social worker, community developer and the first woman elected to serve as Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation. Born in

Tahlequah, Oklahoma

Tahlequah ( ; ''Cherokee'': ᏓᎵᏆ, ''daligwa'' ) is a city in Cherokee County, Oklahoma located at the foothills of the Ozark Mountains. It is part of the Green Country region of Oklahoma and was established as a capital of the 19th-cent ...

, she lived on her family's allotment in Adair County, Oklahoma

Adair County is a county located in the U.S. state of Oklahoma. As of the 2010 census, the population was 22,286. Its county seat is Stilwell. Adair County was named after the Adair family of the Cherokee tribe. One source says that the co ...

, until the age of 11, when her family relocated to San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish for " Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the fourth most populous in California and 17th ...

as part of a federal government program to urbanize Native Americans. After high school, she married a well-to-do Ecuadorian and raised two daughters. Inspired by the social and political movements of the 1960s, Mankiller became involved in the Occupation of Alcatraz

The Occupation of Alcatraz (November 20, 1969 – June 11, 1971) was a 19-month long protest when 89 Native Americans and their supporters occupied Alcatraz Island. The protest was led by Richard Oakes, LaNada Means, and others, while John T ...

and later participated in the land and compensation struggles with the Pit River Tribe

The Pit River Tribe is a federally recognized tribe of eleven bands of indigenous peoples of California. They primarily live along the Pit River in the northeast corner of California.Bell, Oklahoma, was featured in the movie '' The Cherokee Word for Water'', directed by Charlie Soap and Tim Kelly. In 2015, the movie was selected as the top American Indian film of the past 40 years by the American Indian Film Institute. Her project in Kenwood received the Department of Housing and Urban Development's Certificate of National Merit.

Her management ability came to the notice of the incumbent Principal Chief,

In 1964, a small group of

In 1964, a small group of

Ross Swimmer Ross or ROSS may refer to:

People

* Clan Ross, a Highland Scottish clan

* Ross (name), including a list of people with the surname or given name Ross, as well as the meaning

* Earl of Ross, a peerage of Scotland

Places

* RoSS, the Republic of Sout ...

, who invited her to run as his deputy in the 1983 tribal elections. When the duo won, she became the first elected woman to serve as Deputy Chief of the Cherokee Nation. In 1985, when Swimmer took a position in the federal administration of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, she was elevated to Principal Chief, serving until 1995. During her administration, the Cherokee government built new health clinics, created a mobile eye-care clinic, established ambulance services, and created early education, adult education and job training programs. She developed revenue streams, including factories, retail stores, restaurants and bingo operations, while establishing self-governance, allowing the tribe to manage its own finances.

When she retired from politics, Mankiller returned to her activist role as an advocate working to improve the image of Native Americans and combat the misappropriation of native heritage, by authoring books including a bestselling autobiography, ''Mankiller: A Chief and Her People'', and giving numerous lectures on health care, tribal sovereignty, women's rights and cancer awareness. Throughout her life, she had serious health problems, including polycystic kidney disease

Polycystic kidney disease (PKD or PCKD, also known as polycystic kidney syndrome) is a genetic disorder in which the renal tubules become structurally abnormal, resulting in the development and growth of multiple cysts within the kidney. These c ...

, myasthenia gravis, lymphoma

Lymphoma is a group of blood and lymph tumors that develop from lymphocytes (a type of white blood cell). In current usage the name usually refers to just the cancerous versions rather than all such tumours. Signs and symptoms may include enla ...

and breast cancer

Breast cancer is cancer that develops from breast tissue. Signs of breast cancer may include a lump in the breast, a change in breast shape, dimpling of the skin, milk rejection, fluid coming from the nipple, a newly inverted nipple, or a r ...

, and needed two kidney transplants. She died in 2010 from pancreatic cancer, and was honored with many local, state and national awards, including the nation's highest civilian honor, the Presidential Medal of Freedom

The Presidential Medal of Freedom is the highest civilian award of the United States, along with the Congressional Gold Medal. It is an award bestowed by the president of the United States to recognize people who have made "an especially merit ...

.

In 2021 it was announced that Mankiller's likeness would appear on the quarter-dollar coin as a part of the United States Mint's " American Women Quarters" program.

Early life (1945–1955)

Wilma Pearl Mankiller was born on November 18, 1945, in the Hastings Indian Hospital inTahlequah, Oklahoma

Tahlequah ( ; ''Cherokee'': ᏓᎵᏆ, ''daligwa'' ) is a city in Cherokee County, Oklahoma located at the foothills of the Ozark Mountains. It is part of the Green Country region of Oklahoma and was established as a capital of the 19th-cent ...

, to Clara Irene (née Sutton) and Charley Mankiller. Her father was a full-blooded Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, t ...

, whose ancestors had been forced to relocate to Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans who held aboriginal title to their land as a sovereign ...

from Tennessee over the Trail of Tears

The Trail of Tears was an ethnic cleansing and forced displacement of approximately 60,000 people of the " Five Civilized Tribes" between 1830 and 1850 by the United States government. As part of the Indian removal, members of the Cherokee, ...

in the 1830s. Her mother descended from Dutch-Irish and English immigrants who had first settled in Virginia and North Carolina in the 1700s. Her maternal grandparents came to Oklahoma in the early 1900s from Georgia and Arkansas, respectively. The surname "Mankiller", ''Asgaya-dihi'' (Cherokee syllabary

The Cherokee syllabary is a syllabary invented by Sequoyah in the late 1810s and early 1820s to write the Cherokee language. His creation of the syllabary is particularly noteworthy as he was illiterate until the creation of his syllabary. He ...

: ᎠᏍᎦᏯᏗᎯ) in the Cherokee language, refers to a traditional Cherokee military rank, similar to a captain or major, or a shaman

Shamanism is a religious practice that involves a practitioner (shaman) interacting with what they believe to be a spirit world through altered states of consciousness, such as trance. The goal of this is usually to direct spirits or spir ...

with the ability to avenge wrongs through spiritual methods. Alternative spellings are Outacity and Ontassetè. Wilma's given Cherokee name, meaning flower, was ''A-ji-luhsgi''. When Charley and Irene married in 1937, they settled on Charley's father, John Mankiller's allotment, known as "Mankiller Flats", near Rocky Mountain

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in straight-line distance from the northernmost part of western Canada, to New Mexico in ...

in Adair County, Oklahoma

Adair County is a county located in the U.S. state of Oklahoma. As of the 2010 census, the population was 22,286. Its county seat is Stilwell. Adair County was named after the Adair family of the Cherokee tribe. One source says that the co ...

, which he had received in 1907 as part of the government policy of forced assimilation

Forced assimilation is an involuntary process of cultural assimilation of religious or ethnic minority groups during which they are forced to adopt language, identity, norms, mores, customs, traditions, values, mentality, perceptions, way of li ...

for Native American people.

Wilma had five older siblings: Louis Donald "Don", Frieda Marie, Robert Charles, Frances Kay and John David. In 1948, when she was three, the family moved into a house built by her father, her uncle and her brother, Don, on the allotment of her grandfather John. Her five other siblings, Linda Jean, Richard Colson, Vanessa Lou, James Ray and William Edward, were born over the next 12 years. The small house had no electricity or plumbing and they lived in "extreme poverty". The family hunted and fished, maintaining a vegetable garden to feed themselves. They also grew peanuts and strawberries, which they sold. Mankiller went to school through the fifth grade in a three-room schoolhouse, in Rocky Mountain. The family spoke both English and Cherokee at home; even Mankiller's mother spoke Cherokee. Her mother canned food and used flour sacks to make clothes for the children, whom she immersed in Cherokee heritage. Though they joined the Baptist church, the children were wary of white congregants and customs, preferring to attend tribal ceremonial gatherings. Family elders taught the children traditional stories.

Relocation to San Francisco (1956–1976)

In 1955, a severedrought

A drought is defined as drier than normal conditions.Douville, H., K. Raghavan, J. Renwick, R.P. Allan, P.A. Arias, M. Barlow, R. Cerezo-Mota, A. Cherchi, T.Y. Gan, J. Gergis, D. Jiang, A. Khan, W. Pokam Mba, D. Rosenfeld, J. Tierney, an ...

made it more difficult for the family to provide for itself. As a part of the Indian termination policy

Indian termination is a phrase describing United States policies relating to Native Americans from the mid-1940s to the mid-1960s. It was shaped by a series of laws and practices with the intent of assimilating Native Americans into mainstream ...

, the Indian Relocation Act of 1956

The Indian Relocation Act of 1956 (also known as Public Law 959 or the Adult Vocational Training Program) was a United States law intended to create a "a program of vocational training" for Native Americans in the United States. Critics charact ...

provided assistance to relocate Native families to urban areas. Agents from the Bureau of Indian Affairs promised better jobs and living conditions for families that agreed to move. In 1956, when she was 11, her father Charley was denied a loan from the BIA, and decided that moving to a city where he would have a regular income and a steady job would be good for his family. The family chose California because Irene's mother lived in Riverbank. Selling their belongings, they took a train from Stilwell, Oklahoma

Stilwell is a city and county seat of Adair County, Oklahoma, United States. The population was 3,700 as of the 2020 U.S. census, a decline of 6.7 percent from the 3,949 population recorded in 2010. The Oklahoma governor and legislature procla ...

, to San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish for " Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the fourth most populous in California and 17th ...

. Though they were promised an apartment in the city, there were no apartments available when the Mankillers arrived. They were housed in a squalid hotel in the Tenderloin District for several weeks. Even when the family moved to Potrero Hill

Potrero Hill is a residential neighborhood in San Francisco, California. It is known for its views of the San Francisco Bay and city skyline, its proximity to many destination spots, its sunny weather, and having two freeways and a Caltrain stat ...

, where both her father and brother Don found work, the family struggled financially. They had few Native American neighbors, creating alienation from their tribal identities.

Mankiller and her siblings enrolled in school, but it was difficult as the other students made fun of her surname and teased her about her clothes and the way she spoke. Her classmates' treatment caused Mankiller to withdraw. Within a year, the family had saved money and were able to move to Daly City

Daly City () is the second most populous city in San Mateo County, California, United States, with population of 104,901 according to the 2020 census. Located in the San Francisco Bay Area, and immediately south of San Francisco (sharing its ...

, but Mankiller still felt alienated and ran away from home, going to her grandmother's farm in Riverbank. Her grandmother made her return to Potrero, but after Wilma continued to run away, her parents decided to let her live on the farm for a year. By the time she returned, the family had moved again and were living in Hunters Point, a neighborhood riddled with crime, drugs and gangs. Though she had regained her confidence during her year away, Mankiller still felt isolated and began to become involved in the activities of the San Francisco Indian Center. She remained indifferent to school, where she struggled with math and science, but graduated from high school in June 1963.

As soon as she finished school, Mankiller found a clerical job in a finance company and moved in with her sister Frances. That summer, at a Latin dance, she met Hector Hugo Olaya de Bardi, an Ecuadorian

Ecuadorians ( es, ecuatorianos) are people identified with the South American country of Ecuador. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Ecuadorians, several (or all) of these connections exist and are colle ...

college student from a well-to-do family, and the two began dating. Mankiller found him sophisticated, and despite her parents' discomfort with the union, the two married in Reno, Nevada

Reno ( ) is a city in the northwest section of the U.S. state of Nevada, along the Nevada-California border, about north from Lake Tahoe, known as "The Biggest Little City in the World". Known for its casino and tourism industry, Reno is the ...

, on November 13, 1963, and then honeymooned in Chicago. Returning to California, they moved into an apartment in the Mission District

The Mission District (Spanish: ''Distrito de la Misión''), commonly known as The Mission (Spanish: ''La Misión''), is a neighborhood in San Francisco, California. One of the oldest neighborhoods in San Francisco, the Mission District's name is ...

, where 10 months later their daughter Felicia was born. They then moved to a house in a nearby neighborhood and in 1966 had a second daughter, Gina. While Olaya continued with his schooling at San Francisco State University

San Francisco State University (commonly referred to as San Francisco State, SF State and SFSU) is a public research university in San Francisco. As part of the 23-campus California State University system, the university offers 118 different ...

and worked for Pan American Airlines

Pan American World Airways, originally founded as Pan American Airways and commonly known as Pan Am, was an American airline that was the principal and largest international air carrier and unofficial overseas flag carrier of the United States ...

, Mankiller was busy raising their daughters. Olaya saw his role as the family's provider, leaving his wife at home to bring up the children. But Mankiller was restless and returned to school, enrolling in classes at Skyline Junior College. For the first time, she enjoyed school and took only courses that interested her.

Activism

In 1964, a small group of

In 1964, a small group of Red Power

Red is the color at the long wavelength end of the visible spectrum of light, next to orange and opposite violet. It has a dominant wavelength of approximately 625–740 nanometres. It is a primary color in the RGB color model and a secondary ...

activists occupied Alcatraz Island

Alcatraz Island () is a small island in San Francisco Bay, offshore from San Francisco, California, United States. The island was developed in the mid-19th century with facilities for a lighthouse, a military fortification, and a military pri ...

for a few hours. In the late 1960s, a group of students from the University of California at Berkeley

Berkeley most often refers to:

*Berkeley, California, a city in the United States

**University of California, Berkeley, a public university in Berkeley, California

* George Berkeley (1685–1753), Anglo-Irish philosopher

Berkeley may also refer ...

, Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the List of municipalities in California, largest city in the U.S. state, state of California and the List of United States cities by population, sec ...

and Santa Cruz, along with students at San Francisco State, began protesting against the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vietnam a ...

and in favor of civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life o ...

for ethnic minorities and women

A woman is an adult female human. Prior to adulthood, a female human is referred to as a girl (a female child or adolescent). The plural ''women'' is sometimes used in certain phrases such as "women's rights" to denote female humans regardl ...

. Among the groups that sprang up in the period was the American Indian Movement

The American Indian Movement (AIM) is a Native American grassroots movement which was founded in Minneapolis, Minnesota in July 1968, initially centered in urban areas in order to address systemic issues of poverty, discrimination, and police br ...

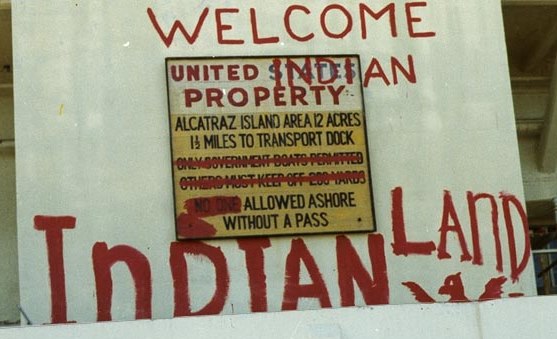

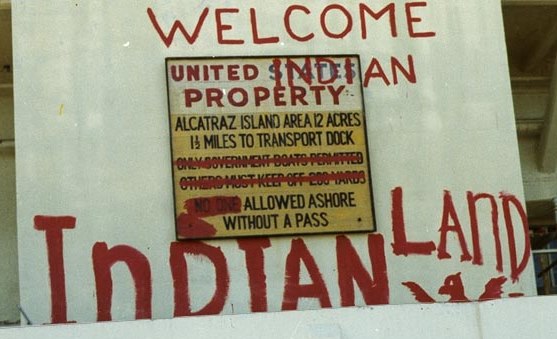

(AIM), which in San Francisco was centered around the activities at the San Francisco Indian Center. Also meeting there was the United Bay Indian Council, which operated as an umbrella organization for 30 separate groups representing people of different tribal affiliations. In October 1969, the Center burned, and the loss of their meeting place created a bond between administrators and student activists, who combined their efforts to bring the plight of urban Native Americans to the public eye with the reoccupation of Alcatraz.

The occupation inspired Mankiller to become involved in civil rights activism. Prior to the November takeover of the island, she had not been involved in either AIM or the United Bay Council. She began to meet with other Native Americans who had participated in the Indian Center, becoming active in the groups supporting the Occupation. While she did visit Alcatraz, most of her work focused on fundraising and support, gathering supplies of blankets, food and water for those on the island. Soon after the Occupation began, Charley Mankiller was diagnosed with kidney disease, which caused Mankiller to discover that she shared polycystic kidney disease

Polycystic kidney disease (PKD or PCKD, also known as polycystic kidney syndrome) is a genetic disorder in which the renal tubules become structurally abnormal, resulting in the development and growth of multiple cysts within the kidney. These c ...

with her father. In between her activism, school and family obligations, she spent as much time with him as she was able. The Occupation lasted 19 months, and during that time, Mankiller learned organizational skills and how to do paralegal research. She had been encouraged by other activists to continue her studies, and began planning a career.

Social work

On her father's death in 1971, the Mankiller family returned to Oklahoma for his burial. When she returned to California, she transferred to San Francisco State University in 1972 and began to focus her classes on social welfare. Against her husband's wishes, she bought her own car and began to seek independence, taking her daughters to Native American events along the West Coast. On her travels, she met members of thePit River Tribe

The Pit River Tribe is a federally recognized tribe of eleven bands of indigenous peoples of California. They primarily live along the Pit River in the northeast corner of California.Burney, and joined their campaign for compensation with the

One of her main duties as deputy chief was to preside over the Tribal Council, the fifteen-member governing body for the Cherokee Nation. Though she assumed that the sexism of the campaign would end once the election was resolved, Mankiller quickly realized that she had little support in the council. Some members viewed her as a political enemy, while others discounted her because of her gender. She chose to avoid involvement in tribal legislation to minimize the hostility to her election, instead concentrating on areas of government that the council did not control. One of her first focus issues was on the full-blood/mixed-blood divide. Cherokees with non-Native ancestry had assimilated into American culture to a greater extent, while full-bloods maintained Cherokee language and culture. The two groups historically had been at odds, with much disagreement on development. By the time Mankiller was elected deputy, the mixed-blood faction focused on economic growth and favored non-Natives being hired to run Native businesses if they were more qualified. Full-bloods believed that such modernization would compromise Cherokee identity. Mankiller, who supported a middle-of-the-road approach, expanded the

One of her main duties as deputy chief was to preside over the Tribal Council, the fifteen-member governing body for the Cherokee Nation. Though she assumed that the sexism of the campaign would end once the election was resolved, Mankiller quickly realized that she had little support in the council. Some members viewed her as a political enemy, while others discounted her because of her gender. She chose to avoid involvement in tribal legislation to minimize the hostility to her election, instead concentrating on areas of government that the council did not control. One of her first focus issues was on the full-blood/mixed-blood divide. Cherokees with non-Native ancestry had assimilated into American culture to a greater extent, while full-bloods maintained Cherokee language and culture. The two groups historically had been at odds, with much disagreement on development. By the time Mankiller was elected deputy, the mixed-blood faction focused on economic growth and favored non-Natives being hired to run Native businesses if they were more qualified. Full-bloods believed that such modernization would compromise Cherokee identity. Mankiller, who supported a middle-of-the-road approach, expanded the

Founding the Private Industry Council, Mankiller brought government and private businesses together to analyze ways to generate economic growth in northeastern Oklahoma. She established employment training opportunities and programs that offered financial and technical expertise to tribal members who wanted to start their own small enterprises. She also backed the creation of a tribal electronic harness and cabling company, construction of a hydroelectric plant and a horticultural operation. Another initiative launched soon after her installment was a claim of compensation from the U.S. government for misappropriating resources from the

Founding the Private Industry Council, Mankiller brought government and private businesses together to analyze ways to generate economic growth in northeastern Oklahoma. She established employment training opportunities and programs that offered financial and technical expertise to tribal members who wanted to start their own small enterprises. She also backed the creation of a tribal electronic harness and cabling company, construction of a hydroelectric plant and a horticultural operation. Another initiative launched soon after her installment was a claim of compensation from the U.S. government for misappropriating resources from the

After her term as chief, in 1996, Mankiller became a visiting professor at

After her term as chief, in 1996, Mankiller became a visiting professor at

In 2021 it was announced that Mankiller, Maya Angelou,

In 2021 it was announced that Mankiller, Maya Angelou,

Mankiller

documentary by Valerie Red-Horse Mohl

Voices of Oklahoma interview with Wilma Mankiller.

First person interview conducted with Wilma Mankiller on August 13, 2009 * {{DEFAULTSORT:Mankiller, Wilma 1945 births 2010 deaths People from Tahlequah, Oklahoma 20th-century Native Americans American autobiographers American feminists American people of Dutch descent American people of Irish descent American people with disabilities American women writers Cherokee Nation writers Cowgirl Hall of Fame inductees Deaths from cancer in Oklahoma Deaths from pancreatic cancer Female Native American leaders Native American activists Native American feminists Native Americans' rights activists Native American women in politics Oklahoma Democrats Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients Principal Chiefs of the Cherokee Nation San Francisco State University alumni Women autobiographers Writers from Oklahoma Native American women writers 20th-century Native American women Activists from Oklahoma Women civil rights activists 21st-century Native Americans 21st-century Native American women

Indian Claims Commission The Indian Claims Commission was a judicial relations arbiter between the United States federal government and Native American tribes. It was established under the Indian Claims Act of 1946 by the United States Congress to hear any longstanding clai ...

and Pacific Gas and Electric Company for lands illegally taken from the tribe during the California Gold Rush. Over the next five years, she assisted the tribe in raising funds for its legal defense and helped prepare documentation for their claim, gaining experience in international and treaty law.

Closer to home, Mankiller founded East Oakland

East Oakland is a geographical region of Oakland, California, United States, that stretches between Lake Merritt in the northwest and San Leandro in the southeast. As the southeastern portion of the city, East Oakland takes up the largest portio ...

's Native American Youth Center, where she served as director. Locating a building, she called for volunteers to paint and help draft educational programs to help youth learn about their heritage, enjoying overwhelming support from the community. In 1974, Mankiller and Olaya divorced and she moved with her two daughters to Oakland. Taking a position as a social worker with the Urban Indian Resource Center, she worked on programs conducting research on child abuse and neglect, foster care, and adoption of Native children. Recognizing that most indigenous children were placed with families with no knowledge of Native traditions, she worked on legislation with other staff and attorneys to prevent children from being removed from their culture. The law, which eventually passed as the Indian Child Welfare Act

The Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978 (ICWA) ((), codified at Indian Child Welfare Act, (, )) is a United States federal law that governs jurisdiction over the removal of American Indian children from their families in custody, foster care and ...

, made it illegal to place Native children in non-Native families.

Return to Oklahoma

Community development (1976–1983)

In 1976, Mankiller's mother returned to Oklahoma, prompting Mankiller to move as well with her two daughters. Initially, she was unable to find work and moved back to California for six months. By the fall, she was back in Oklahoma, and built a small house near her mother's in Mankiller Flats. After doing volunteer work for the Cherokee Nation, Mankiller was hired in 1977 to work on a program for young Cherokees to study environmental science. That same year she enrolled in additional classes at Flaming Rainbow University in Stilwell, Oklahoma, completing herBachelor of Science

A Bachelor of Science (BS, BSc, SB, or ScB; from the Latin ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for programs that generally last three to five years.

The first university to admit a student to the degree of Bachelor of Science was the University o ...

degree in social sciences with an emphasis on Indian Affairs, thanks to a correspondence course under a program offered by the Union for Experimental Colleges in Washington, D.C. She enrolled in graduate courses in community development at the University of Arkansas

The University of Arkansas (U of A, UArk, or UA) is a public land-grant research university in Fayetteville, Arkansas. It is the flagship campus of the University of Arkansas System and the largest university in the state. Founded as Arkansas ...

, in Fayetteville, while continuing to work in the tribal offices as an economic stimulus coordinator. She worked on home health care Homecare (also spelled as home care) is health care or supportive care provided by a professional caregiver in the individual home where the patient or client is living, as opposed to care provided in group accommodations like clinics or nursing ho ...

, the Indian child welfare protocols, language services, a senior citizens program and a youth shelter.

On November 9, 1979, on her way back to Tahlequah from Fayetteville, Mankiller's vehicle was struck by an oncoming car. Sherry Morris, one of Mankiller's closest friends, was driving the other vehicle and died in the crash. Mankiller suffered broken ribs as well as breaks in her left leg and ankle, and both her face and right leg were crushed. Initially doctors thought that she would not regain the ability to walk. After 17 operations and plastic surgery to reconstruct her face, she was released from the hospital able to walk with crutches. While still in recovery from the accident, three months after the collision, Mankiller began to notice a loss of muscle coordination. She dropped things, was unable to grip items, her voice tired after a few moments of speaking. Doctors thought that the problems were related to the accident, but one day while watching a muscular dystrophy telethon, Mankiller thought her symptoms sounded similar. She called the muscular dystrophy center, was referred to a specialist, and was diagnosed with myasthenia gravis. In November 1980, she returned to the hospital, underwent more surgeries and began a course of chemotherapy, which lasted several years. She went back to work in December.

Mankiller's first community development program as a grant writer

Grant writing is the practice of completing an application process for a grant (money), financial grant provided by an institution such as a government department, corporation, foundation (nonprofit organization), foundation, or trust (law), trus ...

was for Bell, Oklahoma. By requiring community members to donate their time and labor to lay 16 miles of pipe for a shared water system, build houses, or work on building rehabilitation, the grant involved the community in self-improvement. Working on the Bell project, Mankiller collaborated with Charlie Soap, who worked in the Indian Housing Authority and helped her supervise the venture. The success of the program led to its use as a model for other grant programs for her own and other tribes. In the midst of the Bell Project, in 1981, tribal chief Ross Swimmer Ross or ROSS may refer to:

People

* Clan Ross, a Highland Scottish clan

* Ross (name), including a list of people with the surname or given name Ross, as well as the meaning

* Earl of Ross, a peerage of Scotland

Places

* RoSS, the Republic of Sout ...

promoted her as first director of a department she devised, the Community Development Department of the Cherokee Nation. Over the next three years, Mankiller raised millions of dollars for similar community development programs. Her approach was one of self-help, which allowed citizens to identify their problems and gain control of the challenges they faced. Impressed by her skill and results, Swimmer asked her to be his running mate for the next tribal election.

Politics (1983–1995)

Deputy Chief (1983–1985)

In 1983, Mankiller, aDemocrat

Democrat, Democrats, or Democratic may refer to:

Politics

*A proponent of democracy, or democratic government; a form of government involving rule by the people.

*A member of a Democratic Party:

**Democratic Party (United States) (D)

**Democratic ...

, was selected as a running mate by Ross Swimmer Ross or ROSS may refer to:

People

* Clan Ross, a Highland Scottish clan

* Ross (name), including a list of people with the surname or given name Ross, as well as the meaning

* Earl of Ross, a peerage of Scotland

Places

* RoSS, the Republic of Sout ...

, a Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

, in a bid for Swimmer's third consecutive term as principal chief. Though they both wanted the tribe to become more self-sufficient, Swimmer felt the path was through developing tribal businesses, like hotels and agricultural enterprises. Mankiller wanted to focus on small rural communities, improving housing and health care. Their differences on policy were not a key problem in the election, but Mankiller's gender was. She was surprised by the sexism

Sexism is prejudice or discrimination based on one's sex or gender. Sexism can affect anyone, but it primarily affects women and girls.There is a clear and broad consensus among academic scholars in multiple fields that sexism refers pri ...

she faced, as in traditional Cherokee society, families and clans were organized matrilineally. Though traditionally women had not held titled positions in Cherokee government, they had a women's council which wielded considerable influence, and were responsible for training the tribal chief. She received death threats, her tires were slashed, and a billboard with her likeness was burned. Swimmer nevertheless remained steadfast. Swimmer won reelection against Perry Wheeler by a narrow margin, on the strength of absentee voters. Mankiller also won by absentee voters in a run-off election for the deputy chief post against Agnes Cowen and became the first woman elected deputy chief of the Cherokee Nation. Wheeler and Cowen demanded a recount and filed a suit with the Cherokee Judicial Appeals Tribunal and U. S. District Court alleging voting irregularities. Both tribal and federal courts ruled against Wheeler and Cowen.

One of her main duties as deputy chief was to preside over the Tribal Council, the fifteen-member governing body for the Cherokee Nation. Though she assumed that the sexism of the campaign would end once the election was resolved, Mankiller quickly realized that she had little support in the council. Some members viewed her as a political enemy, while others discounted her because of her gender. She chose to avoid involvement in tribal legislation to minimize the hostility to her election, instead concentrating on areas of government that the council did not control. One of her first focus issues was on the full-blood/mixed-blood divide. Cherokees with non-Native ancestry had assimilated into American culture to a greater extent, while full-bloods maintained Cherokee language and culture. The two groups historically had been at odds, with much disagreement on development. By the time Mankiller was elected deputy, the mixed-blood faction focused on economic growth and favored non-Natives being hired to run Native businesses if they were more qualified. Full-bloods believed that such modernization would compromise Cherokee identity. Mankiller, who supported a middle-of-the-road approach, expanded the

One of her main duties as deputy chief was to preside over the Tribal Council, the fifteen-member governing body for the Cherokee Nation. Though she assumed that the sexism of the campaign would end once the election was resolved, Mankiller quickly realized that she had little support in the council. Some members viewed her as a political enemy, while others discounted her because of her gender. She chose to avoid involvement in tribal legislation to minimize the hostility to her election, instead concentrating on areas of government that the council did not control. One of her first focus issues was on the full-blood/mixed-blood divide. Cherokees with non-Native ancestry had assimilated into American culture to a greater extent, while full-bloods maintained Cherokee language and culture. The two groups historically had been at odds, with much disagreement on development. By the time Mankiller was elected deputy, the mixed-blood faction focused on economic growth and favored non-Natives being hired to run Native businesses if they were more qualified. Full-bloods believed that such modernization would compromise Cherokee identity. Mankiller, who supported a middle-of-the-road approach, expanded the Cherokee Heritage Center

The Cherokee Heritage Center (Cherokee: Ꮳꮃꭹ Ꮷꮎꮣꮄꮕꮣ Ꭰᏸꮅ) is a non-profit historical society and museum campus that seeks to preserve the historical and cultural artifacts, language, and traditional crafts of the Cherokee. ...

and the Institute for Cherokee Literacy. She persuaded the tribal council to change the way that council members were elected so that rather than at-large candidates, potential members came from newly created districts. The change meant that urban areas with large populations no longer controlled the council membership.

Principal Chief, partial term (1985–1986)

In 1985, Chief Swimmer resigned when appointed assistant secretary of the US Bureau of Indian Affairs. Mankiller succeeded him as the first female principal chief of the Cherokee Nation, when she was sworn into office on December 5, 1985. To appease her detractors on the council, she did not attend council meetings, and stressed the separation between the executive and legislative branches of the government. Almost immediately, the press coverage on Mankiller made her an international celebrity and improved the perception of Native Americans throughout the country. In articles such as a November 1985 interview in ''People

A person ( : people) is a being that has certain capacities or attributes such as reason, morality, consciousness or self-consciousness, and being a part of a culturally established form of social relations such as kinship, ownership of prope ...

'', Mankiller strove to show that Native cultural traditions of cooperation and respect for the environment made them role models for the rest of society. In an interview with ''Ms.

Ms. (American English) or Ms (British English; normally , but also , or when unstressed)''Oxford English Dictionary'' online, Ms, ''n.2''. Etymology: "An orthographic and phonetic blend of Mrs ''n.1'' and miss ''n.2'' Compare mizz ''n.'' The pr ...

'', she pointed out that Cherokee women had been valued members of their communities before mainstream society imposed patriarchy upon the tribe. In presenting her critiques of Reagan administration

Ronald Reagan's tenure as the 40th president of the United States began with his first inauguration on January 20, 1981, and ended on January 20, 1989. Reagan, a Republican from California, took office following a landslide victory over ...

policies that might diminish tribal self-determination or threaten their culture, she built relationships with various power brokers. Because she lacked favor with the Tribal Council, she also used her access with the press to educate Cherokee voters on the goals of her administration and her desire to improve housing and health services. Within five months of becoming chief, Mankiller's celebrity status resulted in her election that year as American Indian Woman of the Year, an honor bestowed by the Oklahoma Federation of Indian Women, and her induction into the Oklahoma Women's Hall of Fame. She was awarded an honorary doctorate

An honorary degree is an academic degree for which a university (or other degree-awarding institution) has waived all of the usual requirements. It is also known by the Latin phrases ''honoris causa'' ("for the sake of the honour") or ''ad hon ...

from the University of New England and received a citation for leadership from Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of high ...

.

By 1986, Mankiller and Charlie Soap's relationship had changed from a professional one to a personal one, leading to their engagement early in the year. Not wanting to provoke calls for her to step down, they kept the relationship private until their marriage in October. It nevertheless caused controversy, generating calls for Soap to resign from his position. He resigned, effective with the end of January 1987, which generated further criticism from Mankiller's opponents, who saw the delay as a tactic for Soap to qualify for retirement benefits. Initially, Mankiller's negative experiences dissuaded her from seeking re-election, but after her opponents tried to persuade her not to run, she entered the race with Soap's support. She persuaded voters that the tribe could cooperate with state and federal governments to negotiate favorable terms to improve their opportunities. Soap, as a full-blood Cherokee, was instrumental in taking her message to that faction and defusing the gender issue, by speaking in Cherokee with them about the traditional place of women in Cherokee society. Focusing on budget cuts by the Reagan White House, she highlighted how reductions in funding for low-income housing, health and nutrition programs, and educational initiatives were affecting the tribe. While she recognized that economic development was a priority, Mankiller stressed that business development had to be balanced by addressing social problems.

Weeks before the election, Mankiller was hospitalized for her kidney disease. Her opponents argued that she was medically unfit to lead the tribe. Turnout was high and even though Mankiller won 45% of the vote, tribal law required 50% to avoid a run-off with Perry Wheeler. She won the run-off, but within a week one of her supporters, who had been elected to the Tribal Council, died. The tribal election committee voted to nullify the absentee ballots for the new council membership, and Mankiller petitioned the Judicial Appeals Tribunal, which required a recount including the absentee voters. The council recount gave Mankiller's administration the majority and the seat was filled by a supporter of her policies. Mankiller used the press surrounding her election to combat the negative stereotypes about Native people, stressing their cultural heritage and strengths. She was selected as Newsmaker of the Year by the Association for Women in Communications

The Association for Women in Communications (AWC) is an American professional organization for women in the communications industry.

History

Theta Sigma Phi

The Association for Women in Communications began in 1909 as Theta Sigma Phi (), an ho ...

and as ''Ms.'' magazine's Woman of the Year for 1987, and was featured in the article "Celebration of Heroes" in ''Newsweek

''Newsweek'' is an American weekly online news magazine co-owned 50 percent each by Dev Pragad, its president and CEO, and Johnathan Davis, who has no operational role at ''Newsweek''. Founded as a weekly print magazine in 1933, it was widely ...

''′s July 1987 edition.

Principal Chief, first elected term (1987–1991)

One of Mankiller's first initiatives was to lobby for maintaining the operation of the Talking Leaves Job Corps Center, which the U.S. Department of Labor had placed on a list for closure. Officials agreed to suspend the closure if she could find a suitable location. She recommended that the job center be housed in the financially insolvent motel, but initially the Tribal Council denied her permission. She was able to reverse their decision by promising to take the issue directly to a vote of the tribal members. She also expanded community development programs, using the Bell Project model, and in 1987 the Kenwood Project won the Department of Housing and Urban Development's Certificate of National Merit. Announcing that the Cherokee government would not wholly fund the Heritage Center, she pressed the center to become more proactive in attracting tourists and generating income to pay for its own operational expenses. When theIndian Gaming Regulatory Act

The Indian Gaming Regulatory Act (, ''et seq.'') is a 1988 United States federal law that establishes the jurisdictional framework that governs Indian gaming. There was no federal gaming structure before this act. The stated purposes of the ac ...

of 1988 passed, Mankiller remained cautious about participating, though she acknowledged that other tribes had a right to do so. Concerned by research connecting gambling and crime, she did not endorse gaming for the Cherokee Nation. She also rejected requests for the tribe to store nuclear waste, given its potential to harm the environment. Eventually, she changed her stance and bingo parlors became a major revenue source for the tribe.

Founding the Private Industry Council, Mankiller brought government and private businesses together to analyze ways to generate economic growth in northeastern Oklahoma. She established employment training opportunities and programs that offered financial and technical expertise to tribal members who wanted to start their own small enterprises. She also backed the creation of a tribal electronic harness and cabling company, construction of a hydroelectric plant and a horticultural operation. Another initiative launched soon after her installment was a claim of compensation from the U.S. government for misappropriating resources from the

Founding the Private Industry Council, Mankiller brought government and private businesses together to analyze ways to generate economic growth in northeastern Oklahoma. She established employment training opportunities and programs that offered financial and technical expertise to tribal members who wanted to start their own small enterprises. She also backed the creation of a tribal electronic harness and cabling company, construction of a hydroelectric plant and a horticultural operation. Another initiative launched soon after her installment was a claim of compensation from the U.S. government for misappropriating resources from the Arkansas River

The Arkansas River is a major tributary of the Mississippi River. It generally flows to the east and southeast as it traverses the U.S. states of Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Arkansas. The river's source basin lies in the western United Stat ...

. The U.S. Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

ruled in ''Choctaw Nation v. Oklahoma'' that the Cherokee, Choctaw and Chickasaw Nation

The Chickasaw Nation (Chickasaw: Chikashsha I̠yaakni) is a federally recognized Native American tribe, with its headquarters located in Ada, Oklahoma in the United States. They are an Indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands, original ...

s owned the banks and riverbed of the Arkansas River. At issue was whether the tribes were entitled to be paid for the loss of access to coal, gas and oil deposits, which could no longer be extracted as the United States Army Corps of Engineers

, colors =

, anniversaries = 16 June (Organization Day)

, battles =

, battles_label = Wars

, website =

, commander1 = ...

had rerouted the river during the construction of the McClellan–Kerr Arkansas River Navigation System

The McClellan–Kerr Arkansas River Navigation System (MKARNS) is part of the United States inland waterway system originating at the Tulsa Port of Catoosa and running southeast through Oklahoma and Arkansas to the Mississippi River. The total ...

. The Cherokee then sued the United States for compensation, and the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that the tribe was entitled to it, though the claim was reversed by the Supreme Court. The three tribes filed a claim in the United States Court of Federal Claims

The United States Court of Federal Claims (in case citations, Fed. Cl. or C.F.C.) is a United States federal court that hears monetary claims against the U.S. government. It was established by statute in 1982 as the United States Claims Court, ...

in 1989 alleging "mismanagement of tribal trust resources".

In December 1988, Mankiller's leadership was recognized with a national award bestowed by the Independent Sector

Independent Sector is a coalition of nonprofits, foundations and corporate giving programs. Founded in 1980, it is the first organization to combine the grant seekers and grantees.

Located in Washington, D.C., Independent Sector largely works on f ...

, an umbrella group for non-profit organizations. The John W. Gardner Leadership Award recognized not only her community development projects, but also her administration of Cherokee Nation Industries, which had seen profits soar to over $2 million. In the middle of her first term, Mankiller was invited to the White House to meet with President Reagan to discuss Native peoples' grievances with his administration. Thinking that it was going to be a productive meeting, Mankiller, who had been chosen as one of the three spokespeople for the 16 invited chiefs, was disappointed that Reagan discounted their issues and merely reiterated his pledge for self-determination. Though she brushed off the meeting as a "photo opportunity" for the president, the publicity of the event further enhanced her image with the public. The most significant development in her first full term was the negotiation with the State of Oklahoma for tax sharing on businesses operating on Cherokee lands. The compact, signed by Governor David Walters

David Lee Walters (born November 20, 1951) is an American politician who was the 24th governor of Oklahoma from 1991 to 1995.

Born in Canute, Oklahoma, Walters was a project manager for Governor David Boren and the youngest executive officer ...

and leadership of all of the Five Civilized Tribes

The term Five Civilized Tribes was applied by European Americans in the colonial and early federal period in the history of the United States to the five major Native American nations in the Southeast—the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek ...

except the Muscogee (Creek) Nation

The Muscogee Nation, or Muscogee (Creek) Nation, is a federally recognized Native American tribe based in the U.S. state of Oklahoma. The nation descends from the historic Muscogee Confederacy, a large group of indigenous peoples of the South ...

, allowed the chiefs to collect state taxes and retain a portion of the revenues.

In June 1990, Mankiller's kidney disease worsened and one of her kidneys failed. Her brother Don donated one of his kidneys, and she underwent a kidney transplant

Kidney transplant or renal transplant is the organ transplant of a kidney into a patient with end-stage kidney disease (ESRD). Kidney transplant is typically classified as deceased-donor (formerly known as cadaveric) or living-donor transplantati ...

in July, returning to work within a few weeks. While she was in Boston recuperating from the transplant, she met with officials from Washington, D.C., and signed an agreement for the Cherokee Nation to participate in a project that allowed the tribe to self-govern and assume responsibility for the use of federal funds. This change in policy had come about because of allegations of corruption and mismanagement in the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Hearings on the matter resulted in amendments in 1988 to the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975

The Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975 (Public Law 93-638) authorized the Secretary of the Interior, the Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare, and some other government agencies to enter into contracts with, ...

, to allow ten tribes to participate in a pilot program spanning five years. Tribes received block grants and were allowed to tailor the use of funds based on local needs. Further amendments in the early 1990s extended self-determination to the Indian Health Service

The Indian Health Service (IHS) is an operating division (OPDIV) within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). IHS is responsible for providing direct medical and public health services to members of federally-recognized Nativ ...

. Mankiller welcomed the initiative, which reinforced intergovernmental cooperation and increased self-determination. During her first full administration, her government built new health clinics, created a mobile eye-care clinic and established ambulance services. They also created early education and adult education programs. Mankiller was recognized with an honorary degree from Yale University

Yale University is a Private university, private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the List of Colonial Colleges, third-oldest institution of higher education in the United Sta ...

in 1990 and from Dartmouth College

Dartmouth College (; ) is a private research university in Hanover, New Hampshire. Established in 1769 by Eleazar Wheelock, it is one of the nine colonial colleges chartered before the American Revolution. Although founded to educate Native ...

in 1991.

Around the same time, the contentious relationship with the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians

The United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians in Oklahoma ( or , abbreviated United Keetoowah Band or UKB) is a federally recognized tribe of Cherokee Native Americans headquartered in Tahlequah, Oklahoma. According to the UKB website, its member ...

flared again. Under Swimmer, the Cherokee Nation had filed a lawsuit against the Keetoowah Band, which traditionally had allowed members to belong to both federally recognized tribes. Mankiller had hoped to reconcile the differences between the two tribes, but the tax compact created controversy. The Keetoowah Band refused to allow the Cherokee Nation to collect taxes from its members and began a policy of requiring their tribal members to withdraw from the Cherokee Nation, claiming to be the "true" tribe representing Cherokee people. Mankiller, whose administration had established a district court to deal with the problem of Indian country being in federal jurisdiction rather than falling under state or local law enforcement, began a practice in late 1990 of negotiating cross-deputation agreements with law enforcement agencies and the Cherokee Nation Marshal Service. (Cross-deputation became formally authorized in April 1991). Raids conducted by county officials and Cherokee Marshals on 14 smoke shops licensed by the Keetoowah Band were carried out in the fall of 1990. Officials of the band failed to obtain a restraining order against the Cherokee Nation and took their grievance to the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Unable to resolve the matter, the federal courts stepped in and ruled that the smoke shops of the Keetoowah Band were not exempt from state taxes.

Principal Chief, second elected term (1991–1995)

In March 1991, Mankiller announced her candidacy for the next election and shortly thereafter was invited to meet with other Indian leaders at the White House with President George H. W. Bush. Bush's officials, unlike Reagan's, were receptive to input from tribal leaders, and Mankiller hoped that a new era of "government-to-government relationships" would follow. In the June election, she won 83% of the vote. One of her first actions was to participate in a conference on educational programs for Native Americans, where she strongly opposed centralizing Indian education. Similarly, she opposed legislation proposed by the Oklahoma House of Representatives to collect cigarette taxes on products sold at Indian smoke shops to non-Indians. In the continuing battle over compensation for the loss of access tomineral rights

Mineral rights are property rights to exploit an area for the minerals it harbors. Mineral rights can be separate from property ownership (see Split estate). Mineral rights can refer to sedentary minerals that do not move below the Earth's surfac ...

owned by the tribe in the Arkansas River, Mankiller estimated that one-third of her time as chief was spent on trying to obtain a settlement.

During the school term of 1991–1992, Mankiller's administration revived the tribal Sequoyah High School in Tahlequah. Working with the American Association of University Women, she worked on a grant program to match Cherokee mentors with girls attending the boarding school. The mentors shadowed the girls through their schooling and provided guidance on career opportunities. She also focused on issues of identity throughout her second term. Mankiller worked with tribal registrar Lee Fleming and a staff member Richard Allen to document groups which claimed Cherokee heritage, and they compiled a list of 269 associations throughout the country. After the passage of the Indian Arts and Crafts Act of 1990

The Indian Arts and Crafts Act of 1990 (P.L. 101-644) is a truth-in-advertising law which prohibits misrepresentation in marketing of American Indian or Alaska Native arts and crafts products within the United States. It is illegal to offer or d ...

, which provided both civil and criminal penalties for non-Native artists who promoted their work as "Indian Art", the tribe had the ability to certify artisans who could not prove their ancestry. In two highly publicized cases, involving Willard Stone

Willard Stone (February 29, 1916 – March 5, 1985)David C. Hunt at Oklahoma Historical Societybr>''Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture'' (retrieved March 20, 2009). was an American artist best known for his wood sculptures carved in a fl ...

and Bert Seabourn, Stone was certified, but his family asked for his certification to be removed, and Seabourn was not certified as an artist, but instead as a "goodwill ambassador".

Mankiller was vocal in her disapproval of relaxing the rigorous Bureau of Indian Affairs' processes for tribal recognition, a stance for which she was frequently criticized. In 1993, she wrote to then-governor of Georgia Zell Miller

Zell Bryan Miller (February 24, 1932 – March 23, 2018) was an American author and politician from the state of Georgia. A Democrat, Miller served as lieutenant governor from 1975 to 1991, 79th Governor of Georgia from 1991 to 1999, and as U. ...

, protesting the state recognition of groups claiming Cherokee and Muscogee (Creek) ancestry. She and other tribal leaders among the Five Civilized Tribes

The term Five Civilized Tribes was applied by European Americans in the colonial and early federal period in the history of the United States to the five major Native American nations in the Southeast—the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek ...

believed that the state recognition process could allow some groups to falsely claim Native heritage. During the congressional hearings on reform of the tribal recognition policies in Washington, D.C., Mankiller stated her opposition to any reform that would weaken the recognition process. During her tenure as chief, the Cherokee tribal council passed two resolutions to bar those without a Certificate of Degree of Indian Blood

A Certificate of Degree of Indian Blood or Certificate of Degree of Alaska Native Blood (both abbreviated CDIB) is an official U.S. document that certifies an individual possesses a specific fraction of Native American ancestry of a federally rec ...

(CDIB) from enrolling in the tribe. The 1988 ''Rules and Regulations of the Cherokee Registration Committee'' required applicants to possess a federal certification that they had ancestry linking them to the Dawes Rolls

The Dawes Rolls (or Final Rolls of Citizens and Freedmen of the Five Civilized Tribes, or Dawes Commission of Final Rolls) were created by the United States Dawes Commission. The commission was authorized by United States Congress in 1893 to exe ...

. The 1992 ''Act Relating to the Process of Enrolling as a Member of the Cherokee Nation'' enacted the policy into law, effectively barring Cherokee Freedmen from citizenship. Mankiller had reaffirmed "Swimmer's order on CDIBs and voting. But in 2004, Lucy Allen, a Freedman descendant, took the matter to the Cherokee Supreme Court, and the court, in a split decision, said that the descendants of Freemen were, in fact, Cherokee, could apply to be enrolled, and should have the right to vote."

In 1992, Mankiller endorsed Bill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton ( né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. He previously served as governor of Arkansas from 1979 to 1981 and agai ...

for president, but did not donate any money to his campaign. She was invited to take part in an economic conference in Little Rock, Arkansas

( The "Little Rock")

, government_type = Council-manager

, leader_title = Mayor

, leader_name = Frank Scott Jr.

, leader_party = D

, leader_title2 = Council

, leader_name2 ...

, and participated in his transition team for the presidency. Thanks to her access to high-level officials, she became the "most influential Indian leader in the country". Her autobiography, ''Mankiller: A Chief and Her People'', published in 1993, became a national best-seller. Gloria Steinem

Gloria Marie Steinem (; born March 25, 1934) is an American journalist and social-political activist who emerged as a nationally recognized leader of second-wave feminism in the United States in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Steinem was a c ...

said in a review, "As one woman's journey, Mankiller opens the heart. As the history of a people, it informs the mind. Together, it teaches us that, as long as people like Wilma Mankiller carry the flame within them, centuries of ignorance and genocide can't extinguish the human spirit". Steinem and Mankiller became close friends, and Steinem later married her partner David Bale

David Charles Howard Bale (2 September 1941 – 30 December 2003) was an English entrepreneur and an environmentalist animal welfare activist. He was the father of actor Christian Bale and the husband of Gloria Steinem.

Early life and backgro ...

in a ceremony at Mankiller Flats. In May, Mankiller received an honorary Doctorate of Humane Letters

The degree of Doctor of Humane Letters (; DHumLitt; DHL; or LHD) is an honorary degree awarded to those who have distinguished themselves through humanitarian and philanthropic contributions to society.

The criteria for awarding the degree differ ...

from Drury College

Drury University, formerly Drury College and originally Springfield College, is a private university in Springfield, Missouri. The university's mission statement describes itself as "church-related". It enrolls about 1,700 undergraduate and grad ...

; in June, she was honored with the American Association of University Women's Achievement Award; and in October was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame. In 1994, she was inducted into the Oklahoma Hall of Fame The Oklahoma Hall of Fame was founded in 1927 by Anna B. Korn to officially celebrate Statehood Day, recognize Oklahomans dedicated to their communities, and provide educational programming for all ages. The first Oklahoma Hall of Fame Induction Cer ...

, as well as the National Cowgirl Museum and Hall of Fame

The National Cowgirl Museum and Hall of Fame is located in Fort Worth, Texas, US. Established in 1975, it is dedicated to honoring women of the American West who have displayed extraordinary courage and pioneering fortitude. The museum is an edu ...

in Fort Worth, Texas

Fort Worth is the fifth-largest city in the U.S. state of Texas and the 13th-largest city in the United States. It is the county seat of Tarrant County, covering nearly into four other counties: Denton, Johnson, Parker, and Wise. Accord ...

. That same year, Mankiller was invited by Clinton to moderate the Nation-to-Nation Summit, in which leaders of all 545 federally recognized tribes in the United States

This is a list of federally recognized tribes in the contiguous United States of America. There are also federally recognized Alaska Native tribes. , 574 Indian tribes were legally recognized by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) of the United ...

were assembled to discuss a variety of topics. The summit provided a forum for tribal leaders and government officials to resolve issues concerning jurisdiction, law, resources and religious freedom. It was followed by a conference held in Albuquerque

Albuquerque ( ; ), ; kee, Arawageeki; tow, Vakêêke; zun, Alo:ke:k'ya; apj, Gołgéeki'yé. abbreviated ABQ, is the most populous city in the U.S. state of New Mexico. Its nicknames, The Duke City and Burque, both reference its founding in ...

, which included the U.S. Attorney General

The United States attorney general (AG) is the head of the United States Department of Justice, and is the chief law enforcement officer of the federal government of the United States. The attorney general serves as the principal advisor to the p ...

and Secretary of the Interior. As a result of the two meetings, the Office of Indian Justice was established by the Department of Justice

A justice ministry, ministry of justice, or department of justice is a ministry or other government agency in charge of the administration of justice. The ministry or department is often headed by a minister of justice (minister for justice in a ...

.

In 1995, Mankiller was diagnosed with lymphoma

Lymphoma is a group of blood and lymph tumors that develop from lymphocytes (a type of white blood cell). In current usage the name usually refers to just the cancerous versions rather than all such tumours. Signs and symptoms may include enla ...

and chose not to run again, largely due to health problems. Because of the chemotherapy, Mankiller had to forgo the immunosuppressive drugs she had been taking since her transplant. When George Bearpaw was disqualified as a candidate, Joe Byrd succeeded her as Principal Chief. Mankiller refused to attend his inauguration, on the grounds that the disqualification of his rival was based on an expunged conviction of assault. Fearing that Byrd would fire the staff she had hired, Mankiller authorized severance packages for the workers in her final days in office. A lawsuit was filed by the new Chief on behalf of the Cherokee Nation against Mankiller, alleging embezzlement of tribal funds of $300,000 paid out to tribal officials and department heads who left at the end of her term in 1995. ''Cherokee Nation v. Mankiller'' was withdrawn by a vote of the tribal council. Reflecting on her chieftainship, Mankiller said, "We've had daunting problems in many critical areas, but I believe in the old Cherokee injunction to 'be of a good mind'. Today it's called positive thinking". When Mankiller left office, the population of the Cherokee Nation had increased from 68,000 to 170,000 citizens. The tribe was generating annual revenues of approximately $25 million from a variety of sources, including factories, retail stores, restaurants and bingo operations. She had secured federal assistance of $125 million annually to assist with education, health, housing and employment programs. Having obtained the tribe's grant for "self-governance", federal oversight of tribal funds was minimized.

Return to activism (1996–2010)

Byrd's administration became embroiled in a constitutional crisis, which he blamed on Mankiller, stating that her failure to attend his inauguration and lack of mentoring divided the tribe and left him without experienced advisors. His supporters also alleged that Mankiller was behind attempts to remove Byrd from office, an allegation she denied. She had remained silent on Byrd's administration until he accused her of heading a conspiracy. Two months after Byrd was accused of improperly using federal funds, and a month after he blamed his administration's issues on Mankiller, she went to Washington with her predecessor, Swimmer, to ask that the federal authorities allow the tribe to sort out their own problems. Despite calls from the US Secretary of the Interior,Bruce Babbitt

The English language name Bruce arrived in Scotland with the Normans, from the place name Brix, Manche in Normandy, France, meaning "the willowlands". Initially promulgated via the descendants of king Robert the Bruce (1274−1329), it has be ...

, for congressional intervention and Oklahoma Senator Jim Inhofe

James Mountain Inhofe ( ; born November 17, 1934) is an American politician serving as the senior United States senator from Oklahoma, a seat he was first elected to in 1994. A member of the Republican Party, he chaired the U.S. Senate Committ ...

's desire for presidential action, Mankiller continued to maintain that the problem was one of inexperienced leadership, in which she did not want to be involved. When an independent group of legal analysts, known as the "Massad Commission", was assembled in 1997 to evaluate the problems in Byrd's administration, Mankiller, in spite of her ongoing health concerns, was called to testify. She reiterated at the hearings that she believed the problems stemmed from poor advisors and the Chief's lack of experience.

After her term as chief, in 1996, Mankiller became a visiting professor at

After her term as chief, in 1996, Mankiller became a visiting professor at Dartmouth College

Dartmouth College (; ) is a private research university in Hanover, New Hampshire. Established in 1769 by Eleazar Wheelock, it is one of the nine colonial colleges chartered before the American Revolution. Although founded to educate Native ...

, where she taught in the Native American Studies program. That year, she was honored with the Elizabeth Blackwell

Elizabeth Blackwell (3 February 182131 May 1910) was a British physician, notable as the first woman to receive a medical degree in the United States, and the first woman on the Medical Register of the General Medical Council for the United Ki ...

Award from Hobart and William Smith Colleges for her exemplary service to humanity. After a semester, she began traveling on a national lecture tour, speaking on health care, tribal sovereignty, women's rights and cancer awareness. She spoke to various civic organizations, tribal gatherings, universities and women's groups. In 1997, she received an honorary degree from Smith College. In 1998, President Clinton awarded Mankiller the Presidential Medal of Freedom

The Presidential Medal of Freedom is the highest civilian award of the United States, along with the Congressional Gold Medal. It is an award bestowed by the president of the United States to recognize people who have made "an especially merit ...

, the highest civilian honor in the United States. Shortly after that, she had a second kidney failure and received a second transplant, from her niece, Virlee Williamson. As previously, she immediately returned to work, resuming her lecture tours and working simultaneously on four books. In 1999 Mankiller was diagnosed with breast cancer and underwent a double-lumpectomy

Lumpectomy (sometimes known as a tylectomy, partial mastectomy, breast segmental resection or breast wide local excision) is a surgical removal of a discrete portion or "lump" of breast tissue, usually in the treatment of a malignant tumor or brea ...

followed by radiation treatment

Radiation therapy or radiotherapy, often abbreviated RT, RTx, or XRT, is a therapy using ionizing radiation, generally provided as part of cancer treatment to control or kill malignant cells and normally delivered by a linear accelerator. Radia ...

. That same year, ''The Reader's Companion to U.S. Women's History'', co-edited by Mankiller, was published.

In 2002, Mankiller contributed to the book '' That Takes Ovaries!: Bold Females and Their Brazen Acts'', and in 2004, she co-authored ''Every Day Is a Good Day: Reflections by Contemporary Indigenous Women''. The following year, she worked with the Oklahoma Breast Cancer Summit to encourage early screening and raise awareness on the disease. In 2006, when Mankiller, along with other Native American leaders, was asked to send a pair of shoes to the Heard Museum

The Heard Museum is a private, not-for-profit museum in Phoenix, Arizona, United States, dedicated to the advancement of American Indian art. It presents the stories of American Indian people from a first-person perspective, as well as exhibitio ...

for the exhibit ''Sole Stories: American Indian Footwear'', she sent a simple pair of walking shoes. She chose the shoes because she had worn them all over the world, including trips from Brazil to China, and because they conveyed the normalcy of her life as well as her durability, steadfastness and determination. In 2007, Mankiller gave the Centennial Lecture in the Humanities for Oklahoma's 100th anniversary of statehood. After the lecture, she was honored with the inaugural Oklahoma Humanities Award by the Oklahoma Humanities Council. She continued her lecture tours and scholarship, and in September 2009 was named the first Sequoyah Institute Fellow at Northeastern State University

Northeastern State University (NSU) is a public university with its main campus in Tahlequah, Oklahoma. The university also has two other campuses in Muskogee and Broken Arrow as well as online. Northeastern is the oldest institution of high ...

.

Death and legacy

In March 2010, her husband announced that Mankiller was terminally ill with pancreatic cancer. Mankiller died on April 6, 2010, from cancer at her home in ruralAdair County, Oklahoma

Adair County is a county located in the U.S. state of Oklahoma. As of the 2010 census, the population was 22,286. Its county seat is Stilwell. Adair County was named after the Adair family of the Cherokee tribe. One source says that the co ...

. About 1,200 people attended her memorial service at the Cherokee National Cultural Grounds in Tahlequah on April 10, including many dignitaries such as sitting Cherokee Chief Chad Smith

Chad Gaylord Smith (born October 25, 1961) is an American musician who has been the drummer of the rock band Red Hot Chili Peppers since 1988. The group was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2012. Smith is also the drummer of the ...

, Oklahoma Governor Brad Henry, U.S. Congressman Dan Boren

David Daniel Boren (born August 2, 1973) is the Secretary of Commerce for the Chickasaw Nation, based in Oklahoma. He is a retired American politician, who served as the U.S. Representative for from 2005 to 2013. The district included most of ...

and Gloria Steinem

Gloria Marie Steinem (; born March 25, 1934) is an American journalist and social-political activist who emerged as a nationally recognized leader of second-wave feminism in the United States in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Steinem was a c ...

. The ceremony included statements from Bill and Hillary Clinton

Hillary Diane Rodham Clinton ( Rodham; born October 26, 1947) is an American politician, diplomat, and former lawyer who served as the 67th United States Secretary of State for President Barack Obama from 2009 to 2013, as a United States sen ...

, as well as President Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II ( ; born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who served as the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party, Obama was the first African-American president of the ...

. Mankiller was buried in the family cemetery, Echota Cemetery, in Stilwell, and a few days later was honored with a Congressional Resolution from the U.S. House of Representatives. She was posthumously presented with the Drum Award for Lifetime Achievement by the Five Civilized Tribes

The term Five Civilized Tribes was applied by European Americans in the colonial and early federal period in the history of the United States to the five major Native American nations in the Southeast—the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek ...

.

Mankiller's papers are housed in the Western History Collection at the University of Oklahoma

, mottoeng = "For the benefit of the Citizen and the State"

, type = Public research university

, established =

, academic_affiliations =

, endowment = $2.7billion (2021)

, pr ...