William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin, (26 June 182417 December 1907) was a British

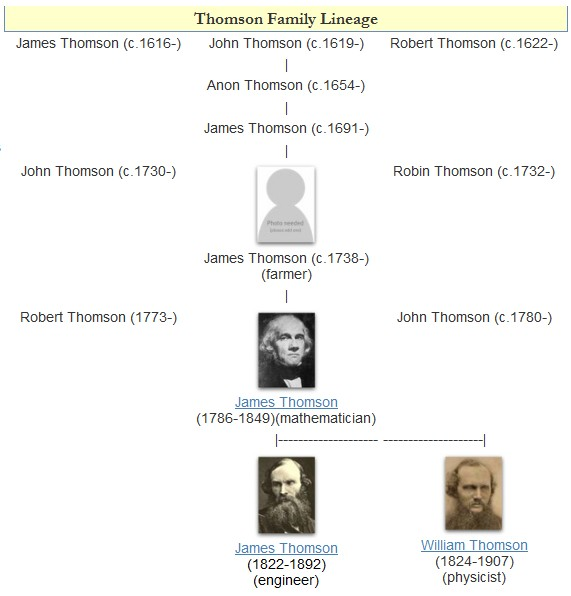

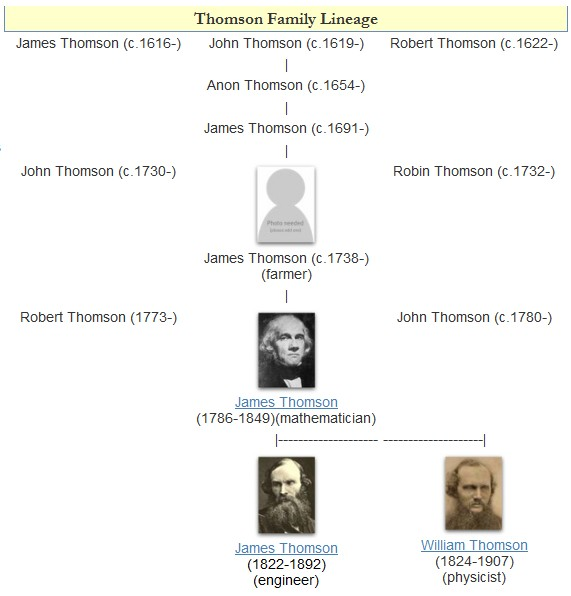

William Thomson's father, James Thomson, was a teacher of mathematics and engineering at the

William Thomson's father, James Thomson, was a teacher of mathematics and engineering at the

Thomson sailed on board the cable-laying ship in August 1857, with Whitehouse confined to land owing to illness, but the voyage ended after when the cable parted. Thomson contributed to the effort by publishing in the ''Engineer'' the whole theory of the

Thomson sailed on board the cable-laying ship in August 1857, with Whitehouse confined to land owing to illness, but the voyage ended after when the cable parted. Thomson contributed to the effort by publishing in the ''Engineer'' the whole theory of the

Kakioka Observatory

in Japan until early 2021. Kelvin may have unwittingly observed atmospheric electrical effects caused by the

Thomson was an enthusiastic yachtsman, his interest in all things relating to the sea perhaps arising from, or fostered by, his experiences on the ''Agamemnon'' and the '' Great Eastern''.

Thomson introduced a method of deep-sea

Thomson was an enthusiastic yachtsman, his interest in all things relating to the sea perhaps arising from, or fostered by, his experiences on the ''Agamemnon'' and the '' Great Eastern''.

Thomson introduced a method of deep-sea

Kelvin made an early physics-based estimation of the

Kelvin made an early physics-based estimation of the

p. 19

/ref> and the quote is instead a paraphrase of

*

*

Treatise on Natural Philosophy (Part I)

' (

Treatise on Natural Philosophy (Part II)

' (

Volume I. 1841-1853

(

Volume II. 1853-1856

(

Volume III. Elasticity, heat, electro-magnetism

(

Volume IV. Hydrodynamics and general dynamics

(Hathitrust) *

Volume V. Thermodynamics, cosmical and geological physics, molecular and crystalline theory, electrodynamics

(

Volume VI. Voltaic theory, radioactivity, electrions, navigation and tides, miscellaneous

(

Volume 1Volume 2

* * * *

''Heroes of the Telegraph''

at

"Horses on Mars", from Lord Kelvin

William Thomson: king of Victorian physics

at

Measuring the Absolute: William Thomson and Temperature

'',

Reprint of papers on electrostatics and magnetism

' (gallica) *

The molecular tactics of a crystal

' (

Quotations. This collection includes sources for many quotes.

'

The Kelvin Library

{{DEFAULTSORT:Kelvin, William Thomson, 1st Baron 1824 births 1907 deaths 19th-century British mathematicians 20th-century British mathematicians Academics of the University of Glasgow Alumni of Peterhouse, Cambridge Alumni of the University of Glasgow Barons in the Peerage of the United Kingdom British physicists Burials at Westminster Abbey Catastrophism Chancellors of the University of Glasgow Elders of the Church of Scotland Fellows of the Royal Society Fluid dynamicists Foreign associates of the National Academy of Sciences John Fritz Medal recipients Knights Bachelor Knights Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order Members of the Order of Merit Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom Members of the Prussian Academy of Sciences Members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences Ordained peers People associated with electricity People educated at the Royal Belfast Academical Institution People of the Industrial Revolution Physicists from Northern Ireland Presidents of the Physical Society Presidents of the Royal Society Presidents of the Royal Society of Edinburgh Recipients of the Pour le Mérite (civil class) Recipients of the Copley Medal Royal Medal winners Second Wranglers Scientists from Belfast Theistic evolutionists Creators of temperature scales Ulster Scots people Scottish Engineering Hall of Fame inductees Recipients of the Matteucci Medal Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society Peers of the United Kingdom created by Queen Victoria

mathematician

A mathematician is someone who uses an extensive knowledge of mathematics in their work, typically to solve mathematical problems.

Mathematicians are concerned with numbers, data, quantity, structure, space, models, and change.

History

On ...

, mathematical physicist and engineer

Engineers, as practitioners of engineering, are professionals who Invention, invent, design, analyze, build and test machines, complex systems, structures, gadgets and materials to fulfill functional objectives and requirements while considerin ...

born in Belfast

Belfast ( , ; from ga, Béal Feirste , meaning 'mouth of the sand-bank ford') is the capital and largest city of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan on the east coast. It is the 12th-largest city in the United Kingdom ...

. Professor of Natural Philosophy at the University of Glasgow

, image = UofG Coat of Arms.png

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Coat of arms

Flag

, latin_name = Universitas Glasguensis

, motto = la, Via, Veritas, Vita

, ...

for 53 years, he did important work in the mathematical analysis

Analysis is the branch of mathematics dealing with continuous functions, limits, and related theories, such as differentiation, integration, measure, infinite sequences, series, and analytic functions.

These theories are usually studied ...

of electricity and formulation of the first and second laws of thermodynamics

The laws of thermodynamics are a set of scientific laws which define a group of physical quantities, such as temperature, energy, and entropy, that characterize thermodynamic systems in thermodynamic equilibrium. The laws also use various paramet ...

, and did much to unify the emerging discipline of physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which ...

in its contemporary form. He received the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

's Copley Medal

The Copley Medal is an award given by the Royal Society, for "outstanding achievements in research in any branch of science". It alternates between the physical sciences or mathematics and the biological sciences. Given every year, the medal is t ...

in 1883, was its president

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

1890–1895, and in 1892 was the first British scientist to be elevated to the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminst ...

.

Absolute temperatures are stated in units of kelvin

The kelvin, symbol K, is the primary unit of temperature in the International System of Units (SI), used alongside its prefixed forms and the degree Celsius. It is named after the Belfast-born and University of Glasgow-based engineer and ...

in his honour. While the existence of a coldest possible temperature (absolute zero

Absolute zero is the lowest limit of the thermodynamic temperature scale, a state at which the enthalpy and entropy of a cooled ideal gas reach their minimum value, taken as zero kelvin. The fundamental particles of nature have minimum vibra ...

) was known prior to his work, Kelvin is known for determining its correct value as approximately −273.15 degrees Celsius

The degree Celsius is the unit of temperature on the Celsius scale (originally known as the centigrade scale outside Sweden), one of two temperature scales used in the International System of Units (SI), the other being the Kelvin scale. The d ...

or −459.67 degrees Fahrenheit

The Fahrenheit scale () is a temperature scale based on one proposed in 1724 by the physicist Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit (1686–1736). It uses the degree Fahrenheit (symbol: °F) as the unit. Several accounts of how he originally defined hi ...

. The Joule–Thomson effect

In thermodynamics, the Joule–Thomson effect (also known as the Joule–Kelvin effect or Kelvin–Joule effect) describes the temperature change of a ''real'' gas or liquid (as differentiated from an ideal gas) when it is forced through a valv ...

is also named in his honour.

He worked closely with mathematics professor Hugh Blackburn

Bailie Hugh Blackburn (; 2 July 1823, Craigflower, Torryburn, Fife – 9 October 1909, Roshven, Inverness-shire) was a Scottish mathematician. A lifelong friend of William Thomson (later Lord Kelvin), and the husband of illustrator Jemima Bla ...

in his work. He also had a career as an electric telegraph

Electrical telegraphs were point-to-point text messaging systems, primarily used from the 1840s until the late 20th century. It was the first electrical telecommunications system and the most widely used of a number of early messaging systems ...

engineer and inventor, which propelled him into the public eye and ensured his wealth, fame and honour. For his work on the transatlantic telegraph project he was knighted

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood finds origins in the G ...

in 1866 by Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previ ...

, becoming Sir William Thomson. He had extensive maritime interests and was most noted for his work on the mariner's compass, which previously had limited reliability.

He was ennobled

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. The characterist ...

in 1892 in recognition of his achievements in thermodynamics, and of his opposition to Irish Home Rule

The Irish Home Rule movement was a movement that campaigned for self-government (or "home rule") for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was the dominant political movement of Irish nationalism from 1870 to the ...

, becoming Baron Kelvin, of Largs

Largs ( gd, An Leargaidh Ghallda) is a town on the Firth of Clyde in North Ayrshire, Scotland, about from Glasgow. The original name means "the slopes" (''An Leargaidh'') in Scottish Gaelic.

A popular seaside resort with a pier, the town mark ...

in the County of Ayr

Ayrshire ( gd, Siorrachd Inbhir Àir, ) is a historic county and registration county in south-west Scotland, located on the shores of the Firth of Clyde. Its principal towns include Ayr, Kilmarnock and Irvine and it borders the counties of R ...

. The title refers to the River Kelvin

The River Kelvin (Scottish Gaelic: ''Abhainn Cheilbhinn'') is a tributary of the River Clyde in northern and northeastern Glasgow, Scotland. It rises on the moor south east of the village of Banton, east of Kilsyth. At almost long, it init ...

, which flows near his laboratory at the University of Glasgow's Gilmorehill

Hillhead ( sco, Hullheid, gd, Ceann a' Chnuic) is an area of Glasgow, Scotland. Situated north of Kelvingrove Park and to the south of the River Kelvin, Hillhead is at the heart of Glasgow's fashionable West End, with Byres Road forming the w ...

home at Hillhead

Hillhead ( sco, Hullheid, gd, Ceann a' Chnuic) is an area of Glasgow, Scotland. Situated north of Kelvingrove Park and to the south of the River Kelvin, Hillhead is at the heart of Glasgow's fashionable West End, with Byres Road forming th ...

. Despite offers of elevated posts from several world-renowned universities, Kelvin refused to leave Glasgow, remaining until his eventual retirement from that post in 1899. Active in industrial research and development, he was recruited around 1899 by George Eastman

George Eastman (July 12, 1854March 14, 1932) was an American entrepreneur who founded the Eastman Kodak Company and helped to bring the photographic use of roll film into the mainstream. He was a major philanthropist, establishing the Eastman ...

to serve as vice-chairman of the board of the British company Kodak Limited, affiliated with Eastman Kodak

The Eastman Kodak Company (referred to simply as Kodak ) is an American public company that produces various products related to its historic basis in analogue photography. The company is headquartered in Rochester, New York, and is incorpor ...

. In 1904 he became Chancellor of the University of Glasgow.

His home was the red sandstone mansion Netherhall, in Largs, which he built in the 1870s and where he died. The Hunterian Museum at the University of Glasgow has a permanent exhibition on the work of Kelvin including many of his original papers, instruments, and other artefacts, such as his smoking pipe.

Early life and work

Family

William Thomson's father, James Thomson, was a teacher of mathematics and engineering at the

William Thomson's father, James Thomson, was a teacher of mathematics and engineering at the Royal Belfast Academical Institution

The Royal Belfast Academical Institution is an independent grammar school in Belfast, Northern Ireland. With the support of Belfast's leading reformers and democrats, it opened its doors in 1814. Until 1849, when it was superseded by what today is ...

and the son of a farmer. James Thomson married Margaret Gardner in 1817 and, of their children, four boys and two girls survived infancy. Margaret Thomson died in 1830 when William was six years old.

William and his elder brother James were tutored at home by their father while the younger boys were tutored by their elder sisters. James was intended to benefit from the major share of his father's encouragement, affection and financial support and was prepared for a career in engineering.

In 1832, his father was appointed professor of mathematics at Glasgow and the family moved there in October 1833. The Thomson children were introduced to a broader cosmopolitan experience than their father's rural upbringing, spending mid-1839 in London and the boys were tutored in French in Paris. Much of Thomson's life during the mid-1840s was spent in Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

and the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

. Language study was given a high priority.

His sister, Anna Thomson, was the mother of James Thomson Bottomley

James Thomson Bottomley (10 January 1845 – 18 May 1926) was an Irish-born British physicist.

He is noted for his work on thermal radiation and on his creation of 4-figure logarithm tables, used to convert long multiplication and division ca ...

FRSE

Fellowship of the Royal Society of Edinburgh (FRSE) is an award granted to individuals that the Royal Society of Edinburgh, Scotland's national academy of science and letters, judged to be "eminently distinguished in their subject". This soci ...

(1845–1926).

Youth

Thomson had heart problems and nearly died when he was 9 years old. He attended theRoyal Belfast Academical Institution

The Royal Belfast Academical Institution is an independent grammar school in Belfast, Northern Ireland. With the support of Belfast's leading reformers and democrats, it opened its doors in 1814. Until 1849, when it was superseded by what today is ...

, where his father was a professor in the university department. In 1834, aged 10, he began studying at the University of Glasgow, not out of any precociousness; the University provided many of the facilities of an elementary school for able pupils, and this was a typical starting age.

In school, Thomson showed a keen interest in the classics along with his natural interest in the sciences. At the age of 12 he won a prize for translating Lucian of Samosata

Lucian of Samosata, '; la, Lucianus Samosatensis ( 125 – after 180) was a Hellenized Syrian satirist, rhetorician and pamphleteer who is best known for his characteristic tongue-in-cheek style, with which he frequently ridiculed superstiti ...

's ''Dialogues of the Gods'' from Ancient Greek to English.

In the academic year 1839/1840, Thomson won the class prize in astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and evolution. Objects of interest include planets, moons, stars, nebulae, g ...

for his ''Essay on the figure of the Earth'' which showed an early facility for mathematical analysis and creativity. His physics tutor at this time was his namesake, David Thomson.

Throughout his life, he would work on the problems raised in the essay as a coping

Coping refers to conscious strategies used to reduce unpleasant emotions. Coping strategies can be cognitions or behaviours and can be individual or social.

Theories of coping

Hundreds of coping strategies have been proposed in an attempt to ...

strategy during times of personal stress

Stress may refer to:

Science and medicine

* Stress (biology), an organism's response to a stressor such as an environmental condition

* Stress (linguistics), relative emphasis or prominence given to a syllable in a word, or to a word in a phrase ...

. On the title page of this essay Thomson wrote the following lines from Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope (21 May 1688 O.S. – 30 May 1744) was an English poet, translator, and satirist of the Enlightenment era who is considered one of the most prominent English poets of the early 18th century. An exponent of Augustan literature, ...

's '' Essay on Man''. These lines inspired Thomson to understand the natural world using the power and method of science:

Thomson became intrigued with Fourier's ''Théorie analytique de la chaleur'' and committed himself to study the "Continental" mathematics resisted by a British establishment still working in the shadow of Sir Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton (25 December 1642 – 20 March 1726/27) was an English mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, Theology, theologian, and author (described in his time as a "natural philosophy, natural philosopher"), widely ...

. Unsurprisingly, Fourier's work had been attacked by domestic mathematicians, Philip Kelland

Philip Kelland PRSE FRS (17 October 1808 – 8 May 1879) was an English mathematician. He was known mainly for his great influence on the development of education in Scotland.

Life

Kelland was born in 1808 the son of Philip Kelland (d.1847), ...

authoring a critical book. The book motivated Thomson to write his first published scientific paper

: ''For a broader class of literature, see Academic publishing.''

Scientific literature comprises scholarly publications that report original empirical and theoretical work in the natural and social sciences. Within an academic field, scienti ...

under the pseudonym ''P.Q.R.'', defending Fourier, and submitted to the ''Cambridge Mathematical Journal'' by his father. A second P.Q.R. paper followed almost immediately.

While on holiday with his family in Lamlash

Lamlash ( gd, An t-Eilean Àrd) is a village on the Isle of Arran, in the Firth of Clyde, Scotland. It lies south of the island's main settlement and ferry port Brodick, in a sheltered bay on the island's east coast, facing the Holy Isle. L ...

in 1841, he wrote a third, more substantial P.Q.R. paper ''On the uniform motion of heat in homogeneous solid bodies, and its connection with the mathematical theory of electricity''. In the paper he made remarkable connections between the mathematical theories of heat conduction

Conduction is the process by which heat is transferred from the hotter end to the colder end of an object. The ability of the object to conduct heat is known as its ''thermal conductivity'', and is denoted .

Heat spontaneously flows along a te ...

and electrostatics

Electrostatics is a branch of physics that studies electric charges at rest ( static electricity).

Since classical times, it has been known that some materials, such as amber, attract lightweight particles after rubbing. The Greek word for a ...

, an analogy

Analogy (from Greek ''analogia'', "proportion", from ''ana-'' "upon, according to" lso "against", "anew"+ ''logos'' "ratio" lso "word, speech, reckoning" is a cognitive process of transferring information or meaning from a particular subject ...

that James Clerk Maxwell

James Clerk Maxwell (13 June 1831 – 5 November 1879) was a Scottish mathematician and scientist responsible for the classical theory of electromagnetic radiation, which was the first theory to describe electricity, magnetism and ligh ...

was ultimately to describe as one of the most valuable ''science-forming ideas.''

Cambridge

William's father was able to make a generous provision for his favourite son's education and, in 1841, installed him, with extensive letters of introduction and ample accommodation, atPeterhouse, Cambridge

Peterhouse is the oldest constituent college of the University of Cambridge in England, founded in 1284 by Hugh de Balsham, Bishop of Ely. Today, Peterhouse has 254 undergraduates, 116 full-time graduate students and 54 fellows. It is quite ...

. While at Cambridge, Thomson was active in sports, athletics and sculling

Sculling is the use of oars to propel a boat by moving them through the water on both sides of the craft, or moving one oar over the stern. A long, narrow boat with sliding seats, rigged with two oars per rower may be referred to as a scull, ...

, winning the Colquhoun Sculls in 1843. He also took a lively interest in the classics, music, and literature; but the real love of his intellectual life was the pursuit of science. The study of mathematics

Mathematics is an area of knowledge that includes the topics of numbers, formulas and related structures, shapes and the spaces in which they are contained, and quantities and their changes. These topics are represented in modern mathematics ...

, physics, and in particular, of electricity, had captivated his imagination. In 1845 Thomson graduated as Second Wrangler

At the University of Cambridge in England, a "Wrangler" is a student who gains first-class honours in the final year of the university's degree in mathematics. The highest-scoring student is the Senior Wrangler, the second highest is the Se ...

. He also won the First Smith's Prize

The Smith's Prize was the name of each of two prizes awarded annually to two research students in mathematics and theoretical physics at the University of Cambridge from 1769. Following the reorganization in 1998, they are now awarded under the n ...

, which, unlike the tripos

At the University of Cambridge, a Tripos (, plural 'Triposes') is any of the examinations that qualify an undergraduate for a bachelor's degree or the courses taken by a student to prepare for these. For example, an undergraduate studying mat ...

, is a test of original research. Robert Leslie Ellis, one of the examiners, is said to have declared to another examiner "You and I are just about fit to mend his pens."

In 1845, he gave the first mathematical development of Michael Faraday

Michael Faraday (; 22 September 1791 – 25 August 1867) was an English scientist who contributed to the study of electromagnetism and electrochemistry. His main discoveries include the principles underlying electromagnetic inducti ...

's idea that electric induction takes place through an intervening medium, or "dielectric", and not by some incomprehensible "action at a distance". He also devised the mathematical technique of electrical images, which became a powerful agent in solving problems of electrostatics, the science which deals with the forces between electrically charged bodies at rest. It was partly in response to his encouragement that Faraday undertook the research in September 1845 that led to the discovery of the Faraday effect

The Faraday effect or Faraday rotation, sometimes referred to as the magneto-optic Faraday effect (MOFE), is a physical magneto-optical phenomenon. The Faraday effect causes a polarization rotation which is proportional to the projection of the ...

, which established that light and magnetic (and thus electric) phenomena were related.

He was elected a fellow of St. Peter's (as Peterhouse was often called at the time) in June 1845. On gaining the fellowship, he spent some time in the laboratory of the celebrated Henri Victor Regnault

Henri Victor Regnault (21 July 1810 – 19 January 1878) was a French chemist and physicist best known for his careful measurements of the thermal properties of gases. He was an early thermodynamicist and was mentor to William Thomson in ...

, at Paris; but in 1846 he was appointed to the chair of natural philosophy in the University of Glasgow

, image = UofG Coat of Arms.png

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Coat of arms

Flag

, latin_name = Universitas Glasguensis

, motto = la, Via, Veritas, Vita

, ...

. At twenty-two he found himself wearing the gown of a professor in one of the oldest Universities in the country, and lecturing to the class of which he was a first year student a few years before.

Thermodynamics

By 1847, Thomson had already gained a reputation as a precocious and maverick scientist when he attended theBritish Association for the Advancement of Science

The British Science Association (BSA) is a charity and learned society founded in 1831 to aid in the promotion and development of science. Until 2009 it was known as the British Association for the Advancement of Science (BA). The current Chi ...

annual meeting in Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

. At that meeting, he heard James Prescott Joule making yet another of his, so far, ineffective attempts to discredit the caloric theory

The caloric theory is an obsolete scientific theory that heat consists of a self-repellent fluid called caloric that flows from hotter bodies to colder bodies. Caloric was also thought of as a weightless gas that could pass in and out of pores ...

of heat and the theory of the heat engine

In thermodynamics and engineering, a heat engine is a system that converts heat to mechanical energy, which can then be used to do mechanical work. It does this by bringing a working substance from a higher state temperature to a lower stat ...

built upon it by Sadi Carnot and Émile Clapeyron. Joule argued for the mutual convertibility of heat and mechanical work

In physics, work is the energy transferred to or from an object via the application of force along a displacement. In its simplest form, for a constant force aligned with the direction of motion, the work equals the product of the force stre ...

and for their mechanical equivalence.

Thomson was intrigued but sceptical. Though he felt that Joule's results demanded theoretical explanation, he retreated into an even deeper commitment to the Carnot–Clapeyron school. He predicted that the melting point

The melting point (or, rarely, liquefaction point) of a substance is the temperature at which it changes state from solid to liquid. At the melting point the solid and liquid phase exist in equilibrium. The melting point of a substance depen ...

of ice must fall with pressure

Pressure (symbol: ''p'' or ''P'') is the force applied perpendicular to the surface of an object per unit area over which that force is distributed. Gauge pressure (also spelled ''gage'' pressure)The preferred spelling varies by country a ...

, otherwise its expansion on freezing could be exploited in a '' perpetuum mobile''. Experimental confirmation in his laboratory did much to bolster his beliefs.

In 1848, he extended the Carnot–Clapeyron theory further through his dissatisfaction that the gas thermometer provided only an operational definition

An operational definition specifies concrete, replicable procedures designed to represent a construct. In the words of American psychologist S.S. Stevens (1935), "An operation is the performance which we execute in order to make known a concept." F ...

of temperature. He proposed an ''absolute temperature

Thermodynamic temperature is a quantity defined in thermodynamics as distinct from kinetic theory or statistical mechanics.

Historically, thermodynamic temperature was defined by Kelvin in terms of a macroscopic relation between thermodynamic ...

scale'' in which "a unit of heat descending from a body A at the temperature ''T''° of this scale, to a body B at the temperature (''T''−1)°, would give out the same mechanical effect '' ork', whatever be the number'' T''." Such a scale would be "quite independent of the physical properties of any specific substance." By employing such a "waterfall", Thomson postulated that a point would be reached at which no further heat (caloric) could be transferred, the point of ''absolute zero

Absolute zero is the lowest limit of the thermodynamic temperature scale, a state at which the enthalpy and entropy of a cooled ideal gas reach their minimum value, taken as zero kelvin. The fundamental particles of nature have minimum vibra ...

'' about which Guillaume Amontons

Guillaume Amontons (31 August 1663 – 11 October 1705) was a French scientific instrument inventor and physicist. He was one of the pioneers in studying the problem of friction, which is the resistance to motion when bodies make contact. He is ...

had speculated in 1702. "Reflections on the Motive Power of Heat", published by Carnot in French in 1824, the year of Lord Kelvin's birth, used −267 as an estimate of the absolute zero temperature. Thomson used data published by Regnault to calibrate his scale against established measurements.

In his publication, Thomson wrote:

—But a footnote signalled his first doubts about the caloric theory, referring to Joule's ''very remarkable discoveries''. Surprisingly, Thomson did not send Joule a copy of his paper, but when Joule eventually read it he wrote to Thomson on 6 October, claiming that his studies had demonstrated conversion of heat into work but that he was planning further experiments. Thomson replied on 27 October, revealing that he was planning his own experiments and hoping for a reconciliation of their two views.

Thomson returned to critique Carnot's original publication and read his analysis to the Royal Society of Edinburgh

The Royal Society of Edinburgh is Scotland's national academy of science and letters. It is a registered charity that operates on a wholly independent and non-partisan basis and provides public benefit throughout Scotland. It was established i ...

in January 1849, still convinced that the theory was fundamentally sound. However, though Thomson conducted no new experiments, over the next two years he became increasingly dissatisfied with Carnot's theory and convinced of Joule's. In February 1851 he sat down to articulate his new thinking. He was uncertain of how to frame his theory and the paper went through several drafts before he settled on an attempt to reconcile Carnot and Joule. During his rewriting, he seems to have considered ideas that would subsequently give rise to the second law of thermodynamics

The second law of thermodynamics is a physical law based on universal experience concerning heat and energy interconversions. One simple statement of the law is that heat always moves from hotter objects to colder objects (or "downhill"), unle ...

. In Carnot's theory, lost heat was ''absolutely lost'' but Thomson contended that it was "''lost to man'' irrecoverably; but not lost in the material world". Moreover, his theological

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the s ...

beliefs led Thompson to extrapolate

In mathematics, extrapolation is a type of estimation, beyond the original observation range, of the value of a variable on the basis of its relationship with another variable. It is similar to interpolation, which produces estimates between kn ...

the second law to the cosmos, originating the idea of universal heat death.

Compensation would require ''a creative act or an act possessing similar power'', resulting in a ''rejuvenating universe'' (as Thompson had previously compared universal heat death to a clock running slower and slower, although he was unsure whether it would eventually reach thermodynamic equilibrium

Thermodynamic equilibrium is an axiomatic concept of thermodynamics. It is an internal state of a single thermodynamic system, or a relation between several thermodynamic systems connected by more or less permeable or impermeable walls. In the ...

and ''stop for ever''). Kelvin also formulated the heat death paradox

The heat death paradox, also known as thermodynamic paradox, Clausius' paradox and Kelvin’s paradox, is a ''reductio ad absurdum'' argument that uses thermodynamics to show the impossibility of an infinitely old universe. It was formulated in Feb ...

(Kelvin’s paradox) in 1862

Events

January–March

* January 1 – The United Kingdom annexes Lagos Island, in modern-day Nigeria.

* January 6 – French intervention in Mexico: French, Spanish and British forces arrive in Veracruz, Mexico.

* January ...

, which uses the second law of thermodynamics to disprove the possibility of an infinitely old universe; this paradox was later extended by Rankine Rankine is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* William Rankine (1820–1872), Scottish engineer and physicist

** Rankine body an elliptical shape of significance in fluid dynamics, named for Rankine

** Rankine scale, an absolute-t ...

.

In final publication, Thomson retreated from a radical departure and declared "the whole theory of the motive power of heat is founded on ... two ... propositions, due respectively to Joule, and to Carnot and Clausius." Thomson went on to state a form of the second law:

In the paper, Thomson supported the theory that heat was a form of motion but admitted that he had been influenced only by the thought of Sir Humphry Davy

Sir Humphry Davy, 1st Baronet, (17 December 177829 May 1829) was a British chemist and inventor who invented the Davy lamp and a very early form of arc lamp. He is also remembered for isolating, by using electricity, several elements for ...

and the experiments of Joule and Julius Robert von Mayer, maintaining that experimental demonstration of the conversion of heat into work was still outstanding.

As soon as Joule read the paper he wrote to Thomson with his comments and questions. Thus began a fruitful, though largely epistolary, collaboration between the two men, Joule conducting experiments, Thomson analysing the results and suggesting further experiments. The collaboration lasted from 1852 to 1856, its discoveries including the Joule–Thomson effect

In thermodynamics, the Joule–Thomson effect (also known as the Joule–Kelvin effect or Kelvin–Joule effect) describes the temperature change of a ''real'' gas or liquid (as differentiated from an ideal gas) when it is forced through a valv ...

, sometimes called the Kelvin–Joule effect, and the published results did much to bring about general acceptance of Joule's work and the kinetic theory.

Thomson published more than 650 scientific papers and applied for 70 patents (not all were issued). Regarding science, Thomson wrote the following:

Transatlantic cable

Calculations on data rate

Though now eminent in the academic field, Thomson was obscure to the general public. In September 1852, he married childhood sweetheart Margaret Crum, daughter of Walter Crum; but her health broke down on their honeymoon, and over the next 17 years, Thomson was distracted by her suffering. On 16 October 1854,George Gabriel Stokes

Sir George Gabriel Stokes, 1st Baronet, (; 13 August 1819 – 1 February 1903) was an Irish English physicist and mathematician. Born in County Sligo, Ireland, Stokes spent all of his career at the University of Cambridge, where he was the Luc ...

wrote to Thomson to try to re-interest him in work by asking his opinion on some experiments of Michael Faraday

Michael Faraday (; 22 September 1791 – 25 August 1867) was an English scientist who contributed to the study of electromagnetism and electrochemistry. His main discoveries include the principles underlying electromagnetic inducti ...

on the proposed transatlantic telegraph cable

Transatlantic telegraph cables were undersea cables running under the Atlantic Ocean for telegraph communications. Telegraphy is now an obsolete form of communication, and the cables have long since been decommissioned, but telephone and data a ...

.

Faraday had demonstrated how the construction of a cable would limit the rate at which messages could be sent – in modern terms, the bandwidth. Thomson jumped at the problem and published his response that month. He expressed his results in terms of the data rate that could be achieved and the economic consequences in terms of the potential revenue

In accounting, revenue is the total amount of income generated by the sale of goods and services related to the primary operations of the business.

Commercial revenue may also be referred to as sales or as turnover. Some companies receive rev ...

of the transatlantic undertaking. In a further 1855 analysis, Thomson stressed the impact that the design of the cable would have on its profit

Profit may refer to:

Business and law

* Profit (accounting), the difference between the purchase price and the costs of bringing to market

* Profit (economics), normal profit and economic profit

* Profit (real property), a nonpossessory inter ...

ability.

Thomson contended that the signalling speed through a given cable was inversely proportional to the square

In Euclidean geometry, a square is a regular quadrilateral, which means that it has four equal sides and four equal angles (90- degree angles, π/2 radian angles, or right angles). It can also be defined as a rectangle with two equal-length a ...

of the length of the cable. Thomson's results were disputed at a meeting of the British Association in 1856 by Wildman Whitehouse

Edward Orange Wildman Whitehouse (1 October 1816 – 26 January 1890) was an English surgeon by profession and an electrical experimenter by avocation. He was recruited by entrepreneur Cyrus West Field as Chief Electrician to work on the pi ...

, the electrician

An electrician is a tradesperson specializing in electrical wiring of buildings, transmission lines, stationary machines, and related equipment. Electricians may be employed in the installation of new electrical components or the maintenance ...

of the Atlantic Telegraph Company

The Atlantic Telegraph Company was a company formed on 6 November 1856 to undertake and exploit a commercial telegraph cable across the Atlantic ocean, the first such telecommunications link.

History

Cyrus Field, American businessman and finan ...

. Whitehouse had possibly misinterpreted the results of his own experiments but was doubtless feeling financial pressure as plans for the cable were already well under way. He believed that Thomson's calculations implied that the cable must be "abandoned as being practically and commercially impossible".

Thomson attacked Whitehouse's contention in a letter to the popular '' Athenaeum'' magazine, pitching himself into the public eye. Thomson recommended a larger conductor with a larger cross section of insulation. He thought Whitehouse no fool, and suspected that he might have the practical skill to make the existing design work. Thomson's work had attracted the attention of the project's undertakers. In December 1856, he was elected to the board of directors of the Atlantic Telegraph Company.

Scientist to engineer

Thomson became scientific adviser to a team with Whitehouse as chief electrician and Sir Charles Tilston Bright as chief engineer but Whitehouse had his way with thespecification

A specification often refers to a set of documented requirements to be satisfied by a material, design, product, or service. A specification is often a type of technical standard.

There are different types of technical or engineering specificati ...

, supported by Faraday and Samuel F. B. Morse.

Thomson sailed on board the cable-laying ship in August 1857, with Whitehouse confined to land owing to illness, but the voyage ended after when the cable parted. Thomson contributed to the effort by publishing in the ''Engineer'' the whole theory of the

Thomson sailed on board the cable-laying ship in August 1857, with Whitehouse confined to land owing to illness, but the voyage ended after when the cable parted. Thomson contributed to the effort by publishing in the ''Engineer'' the whole theory of the stress

Stress may refer to:

Science and medicine

* Stress (biology), an organism's response to a stressor such as an environmental condition

* Stress (linguistics), relative emphasis or prominence given to a syllable in a word, or to a word in a phrase ...

es involved in the laying of a submarine cable, and showed that when the line is running out of the ship, at a constant speed, in a uniform depth of water, it sinks in a slant or straight incline from the point where it enters the water to that where it touches the bottom.

Thomson developed a complete system for operating a submarine telegraph that was capable of sending a character

Character or Characters may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Literature

* ''Character'' (novel), a 1936 Dutch novel by Ferdinand Bordewijk

* ''Characters'' (Theophrastus), a classical Greek set of character sketches attributed to The ...

every 3.5 seconds. He patented the key elements of his system, the mirror galvanometer and the siphon recorder

The syphon or siphon recorder is an obsolete electromechanical device used as a receiver for submarine telegraph cables invented by William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin in 1867. It automatically records an incoming telegraph message as a wiggling in ...

, in 1858.

Whitehouse still felt able to ignore Thomson's many suggestions and proposals. It was not until Thomson convinced the board that using purer copper for replacing the lost section of cable would improve data capacity, that he first made a difference to the execution of the project.

The board insisted that Thomson join the 1858 cable-laying expedition, without any financial compensation, and take an active part in the project. In return, Thomson secured a trial for his mirror galvanometer, which the board had been unenthusiastic about, alongside Whitehouse's equipment. Thomson found the access he was given unsatisfactory and the ''Agamemnon'' had to return home following the disastrous storm of June 1858. In London, the board was about to abandon the project and mitigate their losses by selling the cable. Thomson, Cyrus West Field

Cyrus West Field (November 30, 1819July 12, 1892) was an American businessman and financier who, along with other entrepreneurs, created the Atlantic Telegraph Company and laid the first telegraph cable across the Atlantic Ocean in 1858.

Early ...

and Curtis M. Lampson argued for another attempt and prevailed, Thomson insisting that the technical problems were tractable. Though employed in an advisory capacity, Thomson had, during the voyages, developed a real engineer's instincts and skill at practical problem-solving under pressure, often taking the lead in dealing with emergencies and being unafraid to assist in manual work. A cable was completed on 5 August.

Disaster and triumph

Thomson's fears were realized when Whitehouse's apparatus proved insufficiently sensitive and had to be replaced by Thomson's mirror galvanometer. Whitehouse continued to maintain that it was his equipment that was providing the service and started to engage in desperate measures to remedy some of the problems. He succeeded in fatally damaging the cable by applying 2,000 V. When the cable failed completely Whitehouse was dismissed, though Thomson objected and was reprimanded by the board for his interference. Thomson subsequently regretted that he had acquiesced too readily to many of Whitehouse's proposals and had not challenged him with sufficient vigour. A joint committee of inquiry was established by theBoard of Trade

The Board of Trade is a British government body concerned with commerce and industry, currently within the Department for International Trade. Its full title is The Lords of the Committee of the Privy Council appointed for the consideration of ...

and the Atlantic Telegraph Company. Most of the blame for the cable's failure was found to rest with Whitehouse. The committee found that, though underwater cables were notorious in their lack of reliability, most of the problems arose from known and avoidable causes. Thomson was appointed one of a five-member committee to recommend a specification for a new cable. The committee reported in October 1863.

In July 1865, Thomson sailed on the cable-laying expedition of the but the voyage was dogged by technical problems. The cable was lost after had been laid and the project was abandoned. A further attempt in 1866 laid a new cable in two weeks, and then recovered and completed the 1865 cable. The enterprise was now feted as a triumph by the public and Thomson enjoyed a large share of the adulation. Thomson, along with the other principals of the project, was knighted

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood finds origins in the G ...

on 10 November 1866.

To exploit his inventions for signalling on long submarine cables, Thomson now entered into a partnership with C. F. Varley

Cromwell Fleetwood Varley, FRSA (6 April 1828 – 2 September 1883) was an English engineer, particularly associated with the development of the electric telegraph and the transatlantic telegraph cable. He also took interest in the claims of p ...

and Fleeming Jenkin. In conjunction with the latter, he also devised an automatic curb sender, a kind of telegraph key

A telegraph key is a specialized electrical switch used by a trained operator to transmit text messages in Morse code in a telegraphy system. Keys are used in all forms of electrical telegraph systems, including landline (also called wir ...

for sending messages on a cable.

Later expeditions

Thomson took part in the laying of the French Atlanticsubmarine communications cable

A submarine communications cable is a cable laid on the sea bed between land-based stations to carry telecommunication signals across stretches of ocean and sea. The first submarine communications cables laid beginning in the 1850s carried tel ...

of 1869, and with Jenkin was engineer of the Western and Brazilian and Platino-Brazilian cables, assisted by vacation student James Alfred Ewing

Sir James Alfred Ewing MInstitCE (27 March 1855 − 7 January 1935) was a Scottish physicist and engineer, best known for his work on the magnetic properties of metals and, in particular, for his discovery of, and coinage of the word, '' hy ...

. He was present at the laying of the Pará

Pará is a state of Brazil, located in northern Brazil and traversed by the lower Amazon River. It borders the Brazilian states of Amapá, Maranhão, Tocantins, Mato Grosso, Amazonas and Roraima. To the northwest are the borders of Guyana a ...

to Pernambuco

Pernambuco () is a state of Brazil, located in the Northeast region of the country. With an estimated population of 9.6 million people as of 2020, making it seventh-most populous state of Brazil and with around 98,148 km², being the ...

section of the Brazilian coast cables in 1873.

Thomson's wife, Margaret, died on 17 June 1870, and he resolved to make changes in his life. Already addicted to seafaring, in September he purchased a 126-ton schooner

A schooner () is a type of sailing vessel defined by its rig: fore-and-aft rigged on all of two or more masts and, in the case of a two-masted schooner, the foremast generally being shorter than the mainmast. A common variant, the topsail schoo ...

, the ''Lalla Rookh

''Lalla Rookh'' is an Oriental romance by Irish poet Thomas Moore, published in 1817. The title is taken from the name of the heroine of the frame tale, the (fictional) daughter of the 17th-century Mughal emperor Aurangzeb. The work consi ...

'' and used it as a base for entertaining friends and scientific colleagues. His maritime interests continued in 1871 when he was appointed to the Board of Enquiry into the sinking of .

In June 1873, Thomson and Jenkin were on board the ''Hooper'', bound for Lisbon

Lisbon (; pt, Lisboa ) is the capital and largest city of Portugal, with an estimated population of 544,851 within its administrative limits in an area of 100.05 km2. Lisbon's urban area extends beyond the city's administrative limits w ...

with of cable when the cable developed a fault. An unscheduled 16-day stop-over in Madeira

)

, anthem = ( en, "Anthem of the Autonomous Region of Madeira")

, song_type = Regional anthem

, image_map=EU-Portugal_with_Madeira_circled.svg

, map_alt=Location of Madeira

, map_caption=Location of Madeira

, subdivision_type=Sovereign st ...

followed and Thomson became good friends with Charles R. Blandy and his three daughters. On 2 May 1874 he set sail for Madeira on the ''Lalla Rookh''. As he approached the harbour, he signalled to the Blandy residence "Will you marry me?" and Fanny (Blandy's daughter Frances Anna Blandy) signalled back "Yes". Thomson married Fanny, 13 years his junior, on 24 June 1874.

upLord Kelvin by Hubert von Herkomer

Other contributions

Thomson and Tait: ''Treatise on Natural Philosophy''

Over the period 1855 to 1867, Thomson collaborated withPeter Guthrie Tait

Peter Guthrie Tait FRSE (28 April 1831 – 4 July 1901) was a Scottish mathematical physicist and early pioneer in thermodynamics. He is best known for the mathematical physics textbook ''Treatise on Natural Philosophy'', which he co-wrote wi ...

on a text book

A textbook is a book containing a comprehensive compilation of content in a branch of study with the intention of explaining it. Textbooks are produced to meet the needs of educators, usually at educational institutions. Schoolbooks are textbook ...

that founded the study of mechanics

Mechanics (from Ancient Greek: μηχανική, ''mēkhanikḗ'', "of machines") is the area of mathematics and physics concerned with the relationships between force, matter, and motion among physical objects. Forces applied to objec ...

first on the mathematics of kinematics

Kinematics is a subfield of physics, developed in classical mechanics, that describes the motion of points, bodies (objects), and systems of bodies (groups of objects) without considering the forces that cause them to move. Kinematics, as a fiel ...

, the description of motion without regard to force

In physics, a force is an influence that can change the motion of an object. A force can cause an object with mass to change its velocity (e.g. moving from a state of rest), i.e., to accelerate. Force can also be described intuitively as a ...

. The text developed dynamics in various areas but with constant attention to energy

In physics, energy (from Ancient Greek: ἐνέργεια, ''enérgeia'', “activity”) is the quantitative property that is transferred to a body or to a physical system, recognizable in the performance of work and in the form of ...

as a unifying principle.

A second edition appeared in 1879, expanded to two separately bound parts. The textbook set a standard for early education in mathematical physics

Mathematical physics refers to the development of mathematical methods for application to problems in physics. The '' Journal of Mathematical Physics'' defines the field as "the application of mathematics to problems in physics and the developm ...

.

Atmospheric electricity

Kelvin made significant contributions toatmospheric electricity

Atmospheric electricity is the study of electrical charges in the Earth's atmosphere (or that of another planet). The movement of charge between the Earth's surface, the atmosphere, and the ionosphere is known as the global atmospheric electr ...

for the relatively short time for which he worked on the subject, around 1859. He developed several instruments for measuring the atmospheric electric field, using some of the electrometers he had initially developed for telegraph work, which he tested at Glasgow and whilst on holiday on Arran. His measurements on Arran were sufficiently rigorous and well-calibrated that they could be used to deduce air pollution from the Glasgow area, through its effects on the atmospheric electric field. Kelvin's water dropper electrometer was used for measuring the atmospheric electric field at Kew Observatory and Eskdalemuir Observatory

The Eskdalemuir Observatory is a UK national environmental observatory located near Eskdalemuir, Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland.

Built in 1904, its remote location was chosen to minimise electrical interference with geomagnetic instruments, whic ...

for many years, and one was still in use operationally aKakioka Observatory

in Japan until early 2021. Kelvin may have unwittingly observed atmospheric electrical effects caused by the

Carrington event

The Carrington Event was the most intense geomagnetic storm in recorded history, peaking from 1 to 2 September 1859 during solar cycle 10. It created strong auroral displays that were reported globally and caused sparking and even fires in mul ...

(a significant geomagnetic storm) in early September 1859.

Kelvin's vortex theory of the atom

Between 1870 and 1890 the vortex atom theory, which purported that anatom

Every atom is composed of a nucleus and one or more electrons bound to the nucleus. The nucleus is made of one or more protons and a number of neutrons. Only the most common variety of hydrogen has no neutrons.

Every solid, liquid, gas, a ...

was a vortex

In fluid dynamics, a vortex ( : vortices or vortexes) is a region in a fluid in which the flow revolves around an axis line, which may be straight or curved. Vortices form in stirred fluids, and may be observed in smoke rings, whirlpools in ...

in the aether, was popular among British physicists and mathematicians. Thomson pioneered the theory, which was distinct from the seventeenth century vortex theory of Descartes in that Thomson was thinking in terms of a unitary continuum theory, whereas Descartes was thinking in terms of three different types of matter, each relating respectively to emission, transmission, and reflection of light. About 60 scientific papers were written by approximately 25 scientists. Following the lead of Thomson and Tait, the branch of topology

In mathematics, topology (from the Greek words , and ) is concerned with the properties of a geometric object that are preserved under continuous deformations, such as stretching, twisting, crumpling, and bending; that is, without closing ...

called knot theory

In the mathematical field of topology, knot theory is the study of mathematical knots. While inspired by knots which appear in daily life, such as those in shoelaces and rope, a mathematical knot differs in that the ends are joined so it cannot ...

was developed. Kelvin's initiative in this complex study that continues to inspire new mathematics has led to persistence of the topic in history of science

The history of science covers the development of science from ancient times to the present. It encompasses all three major branches of science: natural, social, and formal.

Science's earliest roots can be traced to Ancient Egypt and Meso ...

.

Marine

Thomson was an enthusiastic yachtsman, his interest in all things relating to the sea perhaps arising from, or fostered by, his experiences on the ''Agamemnon'' and the '' Great Eastern''.

Thomson introduced a method of deep-sea

Thomson was an enthusiastic yachtsman, his interest in all things relating to the sea perhaps arising from, or fostered by, his experiences on the ''Agamemnon'' and the '' Great Eastern''.

Thomson introduced a method of deep-sea depth sounding

Depth sounding, often simply called sounding, is measuring the depth of a body of water. Data taken from soundings are used in bathymetry to make maps of the floor of a body of water, such as the seabed topography.

Soundings were traditional ...

, in which a steel piano wire

Piano wire, or "music wire", is a specialized type of wire made for use in piano strings but also in other applications as springs. It is made from tempered high-carbon steel, also known as spring steel, which replaced iron as the material ...

replaces the ordinary hand line. The wire glides so easily to the bottom that "flying soundings" can be taken while the ship is at full speed. A pressure gauge to register the depth of the sinker was added by Thomson.

About the same time he revived the Sumner method of finding a ship's position, and calculated a set of tables for its ready application.

During the 1880s, Thomson worked to perfect the adjustable compass

A compass is a device that shows the cardinal directions used for navigation and geographic orientation. It commonly consists of a magnetized needle or other element, such as a compass card or compass rose, which can pivot to align itself with ...

to correct errors arising from magnetic deviation

Magnetic deviation is the error induced in a compass by ''local'' magnetic fields, which must be allowed for, along with magnetic declination, if accurate bearings are to be calculated. (More loosely, "magnetic deviation" is used by some to mea ...

owing to the increased use of iron in naval architecture

Naval architecture, or naval engineering, is an engineering discipline incorporating elements of mechanical, electrical, electronic, software and safety engineering as applied to the engineering design process, shipbuilding, maintenance, and ...

. Thomson's design was a great improvement on the older instruments, being steadier and less hampered by friction. The deviation due to the ship's magnetism was corrected by movable iron masses at the binnacle. Thomson's innovations involved much detailed work to develop principles identified by George Biddell Airy

Sir George Biddell Airy (; 27 July 18012 January 1892) was an English mathematician and astronomer, and the seventh Astronomer Royal from 1835 to 1881. His many achievements include work on planetary orbits, measuring the mean density of the E ...

and others, but contributed little in terms of novel physical thinking. Thomson's energetic lobbying and networking proved effective in gaining acceptance of his instrument by The Admiralty.

Charles Babbage

Charles Babbage (; 26 December 1791 – 18 October 1871) was an English polymath. A mathematician, philosopher, inventor and mechanical engineer, Babbage originated the concept of a digital programmable computer.

Babbage is considered ...

had been among the first to suggest that a lighthouse

A lighthouse is a tower, building, or other type of physical structure designed to emit light from a system of lamps and lenses and to serve as a beacon for navigational aid, for maritime pilots at sea or on inland waterways.

Lighthouses m ...

might be made to signal a distinctive number by occultations of its light, but Thomson pointed out the merits of the Morse code

Morse code is a method used in telecommunication to encode text characters as standardized sequences of two different signal durations, called ''dots'' and ''dashes'', or ''dits'' and ''dahs''. Morse code is named after Samuel Morse, one ...

for the purpose, and urged that the signals should consist of short and long flashes of the light to represent the dots and dashes.

Electrical standards

Thomson did more than any other electrician up to his time in introducing accurate methods and apparatus for measuring electricity. As early as 1845 he pointed out that the experimental results of William Snow Harris were in accordance with the laws ofCoulomb

The coulomb (symbol: C) is the unit of electric charge in the International System of Units (SI).

In the present version of the SI it is equal to the electric charge delivered by a 1 ampere constant current in 1 second and to elementary char ...

. In the ''Memoirs of the Roman Academy of Sciences'' for 1857 he published a description of his new divided ring electrometer

An electrometer is an electrical instrument for measuring electric charge or electrical potential difference. There are many different types, ranging from historical handmade mechanical instruments to high-precision electronic devices. Modern ...

, based on the old electroscope of Johann Gottlieb Friedrich von Bohnenberger and he introduced a chain or series of effective instruments, including the quadrant electrometer, which cover the entire field of electrostatic measurement. He invented the current balance, also known as the ''Kelvin balance'' or ''Ampere balance'' (''SiC''), for the precise

Precision, precise or precisely may refer to:

Science, and technology, and mathematics Mathematics and computing (general)

* Accuracy and precision, measurement deviation from true value and its scatter

* Significant figures, the number of digit ...

specification of the ampere

The ampere (, ; symbol: A), often shortened to amp,SI supports only the use of symbols and deprecates the use of abbreviations for units. is the unit of electric current in the International System of Units (SI). One ampere is equal to elect ...

, the standard unit

Unit may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* UNIT, a fictional military organization in the science fiction television series ''Doctor Who''

* Unit of action, a discrete piece of action (or beat) in a theatrical presentation

Music

* ''Unit'' (a ...

of electric current

An electric current is a stream of charged particles, such as electrons or ions, moving through an electrical conductor or space. It is measured as the net rate of flow of electric charge through a surface or into a control volume. The movi ...

. From around 1880 he was aided by the electrical engineer Magnus Maclean FRSE

Fellowship of the Royal Society of Edinburgh (FRSE) is an award granted to individuals that the Royal Society of Edinburgh, Scotland's national academy of science and letters, judged to be "eminently distinguished in their subject". This soci ...

in his electrical experiments.

In 1893, Thomson headed an international commission to decide on the design of the Niagara Falls

Niagara Falls () is a group of three waterfalls at the southern end of Niagara Gorge, spanning the Canada–United States border, border between the Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Ontario in Canada and the U.S. state, state ...

power station

A power station, also referred to as a power plant and sometimes generating station or generating plant, is an industrial facility for the generation of electric power. Power stations are generally connected to an electrical grid.

Many ...

. Despite his belief in the superiority of direct current

Direct current (DC) is one-directional flow of electric charge. An electrochemical cell is a prime example of DC power. Direct current may flow through a conductor such as a wire, but can also flow through semiconductors, insulators, or ev ...

electric power transmission

Electric power transmission is the bulk movement of electrical energy from a generating site, such as a power plant, to an electrical substation. The interconnected lines that facilitate this movement form a ''transmission network''. This is d ...

, he endorsed Westinghouse's alternating current

Alternating current (AC) is an electric current which periodically reverses direction and changes its magnitude continuously with time in contrast to direct current (DC) which flows only in one direction. Alternating current is the form in whic ...

system which had been demonstrated at the Chicago World's Fair of that year. Even after Niagara Falls Thomson still held to his belief that direct current was the superior system.

Acknowledging his contribution to electrical standardisation, the International Electrotechnical Commission

The International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC; in French: ''Commission électrotechnique internationale'') is an international standards organization that prepares and publishes international standards for all electrical, electronic and ...

elected Thomson as its first President at its preliminary meeting, held in London on 26–27 June 1906. "On the proposal of the President r Alexander Siemens, Great Britain

R, or r, is the eighteenth letter of the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''ar'' (pronounced ), plural ''ars'', or in Irelan ...

secounded icby Mr Mailloux S Institute of Electrical Engineersthe Right Honorable Lord Kelvin, G.C.V.O.

The Royal Victorian Order (french: Ordre royal de Victoria) is a dynastic order of knighthood established in 1896 by Queen Victoria. It recognises distinguished personal service to the British monarch, Monarchy of Canada, Canadian monarch, Mon ...

, O.M., was unanimously elected first President of the Commission", minutes of the Preliminary Meeting Report read.

Age of the Earth: geology

Kelvin made an early physics-based estimation of the

Kelvin made an early physics-based estimation of the age of the Earth

The age of Earth is estimated to be 4.54 ± 0.05 billion years This age may represent the age of Earth's accretion, or core formation, or of the material from which Earth formed. This dating is based on evidence from radiometric age-dating of ...

. Given his youthful work on the figure of the Earth and his interest in heat conduction, it is no surprise that he chose to investigate the Earth's cooling and to make historical inferences of the Earth's age from his calculations. Thomson was a creationist

Creationism is the religious belief that nature, and aspects such as the universe, Earth, life, and humans, originated with supernatural acts of divine creation. Gunn 2004, p. 9, "The ''Concise Oxford Dictionary'' says that creationism is 'th ...

in a broad sense, but he was not a ' flood geologist' (a view that had lost mainstream scientific support by the 1840s). He contended that the laws of thermodynamics

The laws of thermodynamics are a set of scientific laws which define a group of physical quantities, such as temperature, energy, and entropy, that characterize thermodynamic systems in thermodynamic equilibrium. The laws also use various paramet ...

operated from the birth of the universe and envisaged a dynamic process that saw the organisation and evolution of the Solar System

The Solar System Capitalization of the name varies. The International Astronomical Union, the authoritative body regarding astronomical nomenclature, specifies capitalizing the names of all individual astronomical objects but uses mixed "Solar ...

and other structures, followed by a gradual "heat death". He developed the view that the Earth had once been too hot to support life and contrasted this view with that of uniformitarianism

Uniformitarianism, also known as the Doctrine of Uniformity or the Uniformitarian Principle, is the assumption that the same natural laws and processes that operate in our present-day scientific observations have always operated in the universe in ...

, that conditions had remained constant since the indefinite past. He contended that "This earth, certainly a moderate number of millions of years ago, was a red-hot globe … ."

After the publication of Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended ...

's ''On the Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life''),The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by Me ...

'' in 1859, Thomson saw evidence of the relatively short habitable age of the Earth as tending to contradict Darwin's gradualist explanation of slow natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the heritable traits characteristic of a population over generations. Cha ...

bringing about biological diversity

Biodiversity or biological diversity is the variety and variability of life on Earth. Biodiversity is a measure of variation at the genetic ('' genetic variability''), species ('' species diversity''), and ecosystem ('' ecosystem diversity'') ...

. Thomson's own views favoured a version of theistic evolution

Theistic evolution (also known as theistic evolutionism or God-guided evolution) is a theological view that God creates through laws of nature. Its religious teachings are fully compatible with the findings of modern science, including biologica ...

sped up by divine guidance. His calculations showed that the Sun could not have possibly existed long enough to allow the slow incremental development by evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

– unless it was heated by an energy source beyond the knowledge of Victorian era

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the period of Queen Victoria's reign, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. The era followed the Georgian period and preceded the Edwa ...

science. He was soon drawn into public disagreement with geologists and with Darwin's supporters John Tyndall

John Tyndall FRS (; 2 August 1820 – 4 December 1893) was a prominent 19th-century Irish physicist. His scientific fame arose in the 1850s from his study of diamagnetism. Later he made discoveries in the realms of infrared radiation and the ...

and T. H. Huxley. In his response to Huxley's address to the Geological Society of London (1868) he presented his address "Of Geological Dynamics" (1869) which, among his other writings, challenged the geologists' assertion that the earth must be vastly old, perhaps billions of years in age.Kelvin did pay off gentleman's bet with Strutt on the importance of radioactivity in the Earth. The Kelvin period does exist in the evolution of stars. They shine from gravitational energy for a while (correctly calculated by Kelvin) before fusion and the main sequence begins. Fusion was not understood until well after Kelvin's time.

Thomson's initial 1864 estimate of the Earth's age was from 20 to 400 million years old. These wide limits were due to his uncertainty about the melting temperature of rock, to which he equated the Earth's interior temperature, as well as the uncertainty in thermal conductivities and specific heats of rocks. Over the years he refined his arguments and reduced the upper bound by a factor of ten, and in 1897 Thomson, now Lord Kelvin, ultimately settled on an estimate that the Earth was 20–40 million years old. In a letter published in Scientific American Supplement 1895 Kelvin criticized geologists' estimates of the age of rocks and the age of the earth, including the views published by Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended ...

, as "vaguely vast age".

His exploration of this estimate can be found in his 1897 address to the Victoria Institute

The Victoria Institute, or Philosophical Society of Great Britain, was founded in 1865, as a response to the publication of ''On the Origin of Species'' and ''Essays and Reviews''. Its stated objective was to defend "the great truths revealed in ...

, given at the request of the Institute's president George Stokes, as recorded in that Institute's journal '' Transactions''. Although his former assistant John Perry published a paper in 1895 challenging Kelvin's assumption of low thermal conductivity

The thermal conductivity of a material is a measure of its ability to conduct heat. It is commonly denoted by k, \lambda, or \kappa.

Heat transfer occurs at a lower rate in materials of low thermal conductivity than in materials of high thermal ...

inside the Earth, and thus showing a much greater age, this had little immediate impact. The discovery in 1903 that radioactive decay

Radioactive decay (also known as nuclear decay, radioactivity, radioactive disintegration, or nuclear disintegration) is the process by which an unstable atomic nucleus loses energy by radiation. A material containing unstable nuclei is consid ...

releases heat led to Kelvin's estimate being challenged, and Ernest Rutherford

Ernest Rutherford, 1st Baron Rutherford of Nelson, (30 August 1871 – 19 October 1937) was a New Zealand physicist who came to be known as the father of nuclear physics.

''Encyclopædia Britannica'' considers him to be the greatest ...

famously made the argument in a 1904 lecture attended by Kelvin that this provided the unknown energy source Kelvin had suggested, but the estimate was not overturned until the development in 1907 of radiometric dating

Radiometric dating, radioactive dating or radioisotope dating is a technique which is used to date materials such as rocks or carbon, in which trace radioactive impurities were selectively incorporated when they were formed. The method compares ...

of rocks.

The discovery of radioactivity largely invalidated Kelvin's estimate of the age of the Earth. Although he eventually paid off a gentleman's bet with Strutt on the importance of radioactivity in the Earth's geology, he never publicly acknowledged this because he thought he had a much stronger argument restricting the age of the Sun to no more than 20 million years. Without sunlight, there could be no explanation for the sediment record on the Earth's surface. At the time, the only known source for solar energy was gravitational collapse

Gravitational collapse is the contraction of an astronomical object due to the influence of its own gravity, which tends to draw matter inward toward the center of gravity. Gravitational collapse is a fundamental mechanism for structure formatio ...

. It was only when thermonuclear fusion

Thermonuclear fusion is the process of atomic nuclei combining or “fusing” using high temperatures to drive them close enough together for this to become possible. There are two forms of thermonuclear fusion: ''uncontrolled'', in which the re ...

was recognised in the 1930s that Kelvin's age paradox was truly resolved. However, modern cosmology recognizes the Kelvin period in the early life of a star, during which it shines from gravitational energy (correctly calculated by Kelvin) before fusion and the main sequence begins.

Later life and death

In the winter of 1860–1861 Kelvin slipped on the ice whilecurling

Curling is a sport in which players slide stones on a sheet of ice toward a target area which is segmented into four concentric circles. It is related to bowls, boules, and shuffleboard. Two teams, each with four players, take turns slidi ...