William S. Bruce on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

William Speirs Bruce (1 August 1867 – 28 October 1921) was a British naturalist, polar scientist and

The

The

''Windward'' arrived at Cape Flora on 25 July where Bruce found that Jackson's expedition party had been joined by Fridtjof Nansen and his companion

''Windward'' arrived at Cape Flora on 25 July where Bruce found that Jackson's expedition party had been joined by Fridtjof Nansen and his companion

On his return from Franz Josef Land in 1897, Bruce worked in Edinburgh as an assistant to his former mentor John Arthur Thomson, and resumed his duties at the Ben Nevis observatory. In March 1898 he received an offer to join Major Andrew Coats on a hunting voyage to the Arctic waters around Novaya Zemlya and Spitsbergen, in the private yacht ''Blencathra''. This offer had originally been made to Mill, who was unable to obtain leave from the Royal Geographical Society, and once again suggested Bruce as a replacement. Andrew Coats was a member of the prosperous Coats family of thread manufacturers, who had founded the

On his return from Franz Josef Land in 1897, Bruce worked in Edinburgh as an assistant to his former mentor John Arthur Thomson, and resumed his duties at the Ben Nevis observatory. In March 1898 he received an offer to join Major Andrew Coats on a hunting voyage to the Arctic waters around Novaya Zemlya and Spitsbergen, in the private yacht ''Blencathra''. This offer had originally been made to Mill, who was unable to obtain leave from the Royal Geographical Society, and once again suggested Bruce as a replacement. Andrew Coats was a member of the prosperous Coats family of thread manufacturers, who had founded the

With financial support from the Coats family, Bruce had acquired a

With financial support from the Coats family, Bruce had acquired a

During his Spitsbergen visits with Prince Albert in 1898 and 1899, Bruce had detected the presence of coal,

During his Spitsbergen visits with Prince Albert in 1898 and 1899, Bruce had detected the presence of coal,

The early years of the 21st century have seen a reassessment of Bruce's work. Contributory factors have been the SNAE centenary, and Scotland's renewed sense of national identity. A 2003 expedition, in a modern research ship "Scotia", used information collected by Bruce as a basis for examining climate change in South Georgia. This expedition predicted "dramatic conclusions" relating to global warming from its research, and saw this contribution as a "fitting tribute to Britain's forgotten polar hero, William Speirs Bruce".

An hour-long BBC television documentary on Bruce presented by

The early years of the 21st century have seen a reassessment of Bruce's work. Contributory factors have been the SNAE centenary, and Scotland's renewed sense of national identity. A 2003 expedition, in a modern research ship "Scotia", used information collected by Bruce as a basis for examining climate change in South Georgia. This expedition predicted "dramatic conclusions" relating to global warming from its research, and saw this contribution as a "fitting tribute to Britain's forgotten polar hero, William Speirs Bruce".

An hour-long BBC television documentary on Bruce presented by BBC, The Last Explorers, Episode 2 of 4, William Speirs Bruce

/ref> A new biographer, Peter Speak (2003), claims that the SNAE was "by far the most cost-effective and carefully planned scientific expedition of the Heroic Age". The same author considers reasons why Bruce's efforts to capitalise on this success met with failure, and suggests a combination of his shy, solitary, uncharismatic nature and his "fervent" Scottish nationalism. Bruce seemingly lacked public relations skills and the ability to promote his work, after the fashion of Scott and Shackleton; a lifelong friend described him as being "as prickly as the Scottish thistle itself". On occasion he behaved tactlessly, as with Jackson over the question of the specimens brought back from

William Speirs Bruce Collection at the University of Edinburgh

Retrieved 2017-09-11 {{DEFAULTSORT:Bruce, William 19th-century biologists 19th-century explorers 19th-century Scottish people 1867 births 1921 deaths Academics of Heriot-Watt University Alumni of the University of Edinburgh Explorers of Antarctica Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh People educated at University College School People educated at Watts Naval School People from Kensington Scottish marine biologists Scottish nationalists Scottish naturalists Scottish oceanographers Scottish people of Welsh descent Scottish polar explorers

oceanographer

Oceanography (), also known as oceanology and ocean science, is the scientific study of the oceans. It is an Earth science, which covers a wide range of topics, including ecosystem dynamics; ocean currents, waves, and geophysical fluid dynamic ...

who organized and led the Scottish National Antarctic Expedition

The Scottish National Antarctic Expedition (SNAE), 1902–1904, was organised and led by William Speirs Bruce, a natural scientist and former medical student from the University of Edinburgh. Although overshadowed in terms of prestige by Rob ...

(SNAE, 1902–04) to the South Orkney Islands and the Weddell Sea

The Weddell Sea is part of the Southern Ocean and contains the Weddell Gyre. Its land boundaries are defined by the bay formed from the coasts of Coats Land and the Antarctic Peninsula. The easternmost point is Cape Norvegia at Princess Martha ...

. Among other achievements, the expedition established the first permanent weather station

A weather station is a facility, either on land or sea, with instruments and equipment for measuring atmospheric conditions to provide information for weather forecasts and to study the weather and climate. The measurements taken include tempera ...

in Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean, it contains the geographic South Pole. Antarctica is the fifth-largest cont ...

. Bruce later founded the Scottish Oceanographical Laboratory

The Scottish Oceanographical Laboratory was founded in Nicolson Street, Edinburgh in 1906, by William Speirs Bruce, who had travelled widely in the Antarctic and Arctic regions and had led the Scottish National Antarctic Expedition (SNAE) 1902&nda ...

in Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian on the southern shore of t ...

, but his plans for a transcontinental Antarctic march via the South Pole

The South Pole, also known as the Geographic South Pole, Terrestrial South Pole or 90th Parallel South, is one of the two points where Earth's axis of rotation intersects its surface. It is the southernmost point on Earth and lies antipod ...

were abandoned because of lack of public and financial support.

In 1892 Bruce gave up his medical studies at the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in post-nominals) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted a royal charter by King James VI in 15 ...

and joined the Dundee Whaling Expedition

The Dundee Whaling Expedition (1892–1893) was a commercial voyage from Scotland to Antarctica.

Whaling in the Arctic was in decline from overfishing. The merchants of Dundee decided to equip a fleet to sail all the way to the Weddell Sea in ...

to Antarctica as a scientific assistant. This was followed by Arctic voyages to Novaya Zemlya, Spitsbergen and Franz Josef Land

Franz Josef Land, Frantz Iosef Land, Franz Joseph Land or Francis Joseph's Land ( rus, Земля́ Фра́нца-Ио́сифа, r=Zemlya Frantsa-Iosifa, no, Fridtjof Nansen Land) is a Russian archipelago in the Arctic Ocean. It is inhabited on ...

. In 1899 Bruce, by then Britain's most experienced polar scientist, applied for a post on Robert Falcon Scott

Captain Robert Falcon Scott, , (6 June 1868 – c. 29 March 1912) was a British Royal Navy officer and explorer who led two expeditions to the Antarctic regions: the ''Discovery'' expedition of 1901–1904 and the ill-fated ''Terra Nov ...

's Discovery Expedition

The ''Discovery'' Expedition of 1901–1904, known officially as the British National Antarctic Expedition, was the first official British exploration of the Antarctic regions since the voyage of James Clark Ross sixty years earlier (1839–18 ...

, but delays over this appointment and clashes with Royal Geographical Society (RGS) president Sir Clements Markham

Sir Clements Robert Markham (20 July 1830 – 30 January 1916) was an English geographer, explorer and writer. He was secretary of the Royal Geographical Society (RGS) between 1863 and 1888, and later served as the Society's president for ...

led him instead to organise his own expedition, and earned him the permanent enmity of the geographical establishment in London. Although Bruce received various awards for his polar work, including an honorary doctorate

An honorary degree is an academic degree for which a university (or other degree-awarding institution) has waived all of the usual requirements. It is also known by the Latin phrases ''honoris causa'' ("for the sake of the honour") or ''ad hon ...

from the University of Aberdeen

, mottoeng = The fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom

, established =

, type = Public research universityAncient university

, endowment = £58.4 million (2021)

, budget ...

, neither he nor any of his SNAE colleagues were recommended by the RGS for the prestigious Polar Medal

The Polar Medal is a medal awarded by the Sovereign of the United Kingdom to individuals who have outstanding achievements in the field of polar research, and particularly for those who have worked over extended periods in harsh climates. It ...

.

Between 1907 and 1920 Bruce made many journeys to the Arctic

The Arctic ( or ) is a polar region located at the northernmost part of Earth. The Arctic consists of the Arctic Ocean, adjacent seas, and parts of Canada (Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut), Danish Realm (Greenland), Finland, Iceland, N ...

regions, both for scientific and for commercial purposes. His failure to mount any major exploration ventures after the SNAE is usually attributed to his lack of public relations skills, powerful enemies, and his Scottish nationalism. By 1919 his health was failing, and he experienced several spells in hospital before his death in 1921, after which he was almost totally forgotten. In recent years, following the centenary of the Scottish Expedition, efforts have been made to give fuller recognition to his role in the history of scientific polar exploration.

Early life

Home and school

William Speirs Bruce was born at 43 Kensington Gardens Square in London, the fourth child of Samuel Noble Bruce, a Scottish physician, and hisWelsh

Welsh may refer to:

Related to Wales

* Welsh, referring or related to Wales

* Welsh language, a Brittonic Celtic language spoken in Wales

* Welsh people

People

* Welsh (surname)

* Sometimes used as a synonym for the ancient Britons (Celtic peop ...

wife Mary, née Lloyd. His middle name came from another branch of the family; its unusual spelling, as distinct from the more common "Spiers", tended to cause problems for reporters, reviewers and biographers. William passed his early childhood in the family's London home at 18 Royal Crescent, Holland Park, under the tutelage of his grandfather, the Revd William Bruce. There were regular visits to nearby Kensington Gardens, and sometimes to the Natural History Museum

A natural history museum or museum of natural history is a scientific institution with natural history collections that include current and historical records of animals, plants, fungi, ecosystems, geology, paleontology, climatology, and more. ...

; according to Samuel Bruce these outings first ignited young William's interest in life and nature.

In 1879, at the age of 12, William was sent to a progressive boarding school, Norfolk County School (later Watts Naval School

Watts Naval School was originally the Norfolk County School, a boarding school set up to serve the educational needs of the 'sons of farmers and artisans'. The school was later operated by Dr Barnardo's until closure in 1953.

History Norfolk C ...

) in the village of North Elmham

North Elmham is a village and civil parish in the English county of Norfolk.

It covers an area of and had a population of 1,428 in 624 households at the 2001 census, including Gateley and increasing slightly to 1,433 at the 2011 Census. For ...

, Norfolk. He remained there until 1885, and then spent two further years at University College School

("Slowly but surely")

, established =

, closed =

, type = Public schoolIndependent day school

, religion =

, president =

, head_label = Headmaster

, head = Mark Beard

, r_head_label =

, r_he ...

, Hampstead, preparing for the matriculation examination

A matriculation examination or matriculation exam is a university entrance examination, which is typically held towards the end of secondary school. After passing the examination, a student receives a school leaving certificate recognising academi ...

that would admit him to the medical school at University College London

, mottoeng = Let all come who by merit deserve the most reward

, established =

, type = Public research university

, endowment = £143 million (2020)

, budget = ...

(UCL). He succeeded at his third attempt, and was ready to start his medical studies in the autumn of 1887.

Edinburgh

During mid-1887, Bruce travelled north toEdinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian on the southern shore of t ...

to attend a pair of vacation courses in natural sciences. The six-week courses, at the recently established Scottish Marine Station at Granton on the Firth of Forth, were under the direction of Patrick Geddes

Sir Patrick Geddes (2 October 1854 – 17 April 1932) was a British biologist, sociologist, Comtean positivist, geographer, philanthropist and pioneering town planner. He is known for his innovative thinking in the fields of urban planning ...

and John Arthur Thomson, and included sections on botany

Botany, also called , plant biology or phytology, is the science of plant life and a branch of biology. A botanist, plant scientist or phytologist is a scientist who specialises in this field. The term "botany" comes from the Ancient Greek w ...

and practical zoology

Zoology ()The pronunciation of zoology as is usually regarded as nonstandard, though it is not uncommon. is the branch of biology that studies the animal kingdom, including the structure, embryology, evolution, classification, habits, and ...

. The experience of Granton, and the contact with some of the foremost contemporary natural scientists, convinced Bruce to stay in Scotland. He abandoned his place at UCL, and enrolled instead in the medical school at the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in post-nominals) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted a royal charter by King James VI in 15 ...

. This enabled him to maintain contact with mentors such as Geddes and Thomson, and also gave him the opportunity to work during his free time in the Edinburgh laboratories where specimens brought back from the Challenger expedition

The ''Challenger'' expedition of 1872–1876 was a scientific program that made many discoveries to lay the foundation of oceanography. The expedition was named after the naval vessel that undertook the trip, .

The expedition, initiated by Wi ...

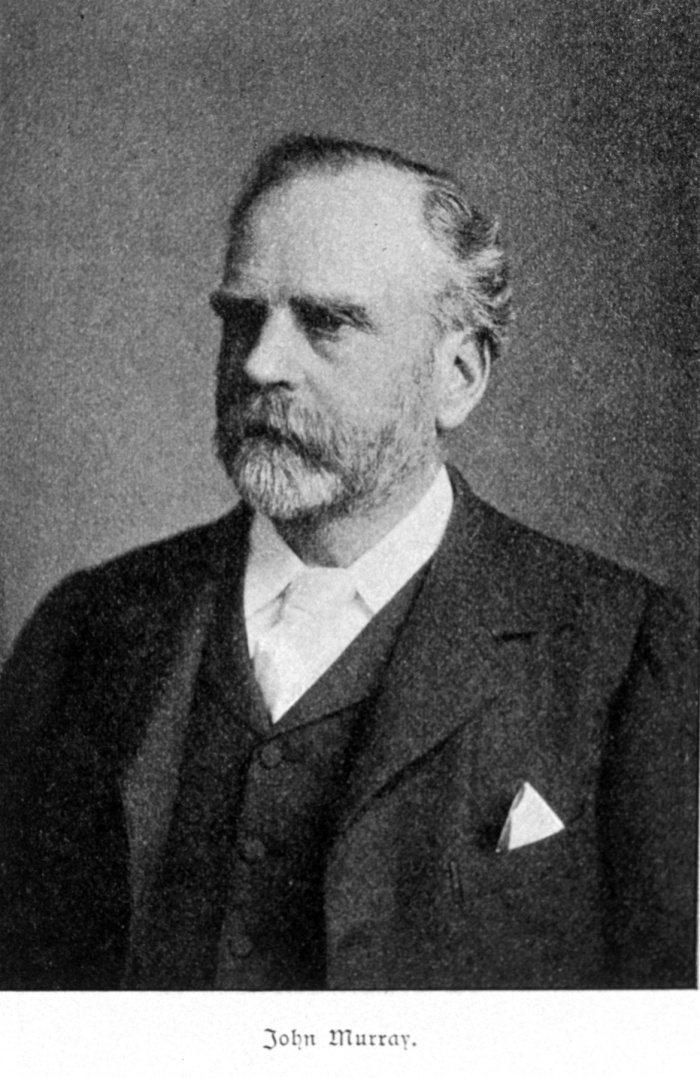

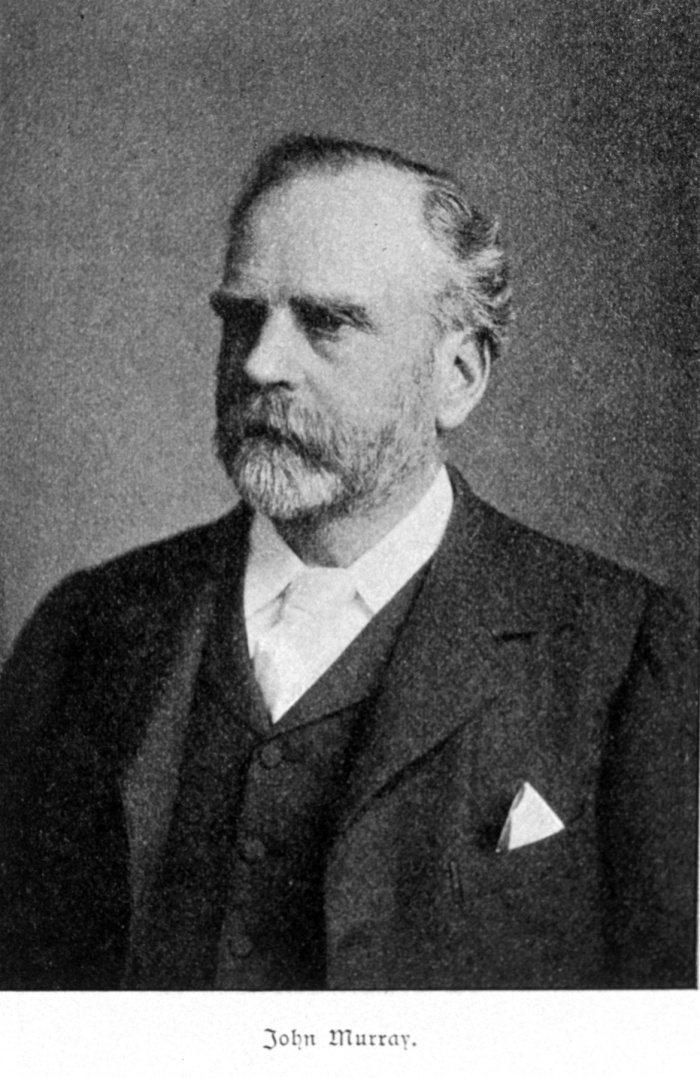

were being examined and classified. Here he worked under Dr John Murray and his assistant John Young Buchanan, and gained a deeper understanding of oceanography and invaluable experience in the principles of scientific investigation.

First voyages

Dundee Whaling Expedition

Dundee Whaling Expedition

The Dundee Whaling Expedition (1892–1893) was a commercial voyage from Scotland to Antarctica.

Whaling in the Arctic was in decline from overfishing. The merchants of Dundee decided to equip a fleet to sail all the way to the Weddell Sea in ...

, 1892–93, was an attempt to investigate the commercial possibilities of whaling in Antarctic waters by locating a source of right whales in the region. Scientific observations and oceanographic research would also be carried out in the four whaling ships: ''Balaena'', ''Active'', ''Diana'' and ''Polar Star''. Bruce was recommended to the expedition by Hugh Robert Mill, an acquaintance from Granton who was now librarian to the Royal Geographical Society in London. Although it would finally curtail his medical studies, Bruce did not hesitate; with William Gordon Burn Murdoch

William Gordon Burn Murdoch (22 January 1862 – 19 July 1939) was a Scottish painter, travel writer and explorer. Murdoch travelled widely including India and both the Arctic and the Antarctic. He is said to be the first person to have played t ...

as an assistant he took up his duties on ''Balaena'' under Capt. Alexander Fairweather. The four ships sailed from Dundee on 6 September 1892.

The relatively short expedition—Bruce was back in Scotland in May 1893—failed in its main purpose, and gave only limited opportunities for scientific work. No right whales were found, and to cut the expedition's losses a mass slaughter of seals was ordered, to secure skins, oil and blubber. Bruce found this distasteful, especially as he was expected to share in the killing. The scientific output from the voyage was, in Bruce's words "a miserable show". In a letter to the Royal Geographical Society he wrote: "The general bearing of the master (Captain Fairweather) was far from being favourable to scientific work".Letter to "Secretaries of the Royal Geographical Society", quoted in . Bruce was denied access to charts, so was unable to establish the accurate location of phenomena. He was required to work "in the boats" when he should have been making meteorological and other observations, and no facilities were allowed him for the preparation of specimens, many of which were lost through careless handling by the crew. Nevertheless, his letter to the RGS ends: "I have to thank the Society for assisting me in what has been, despite all drawbacks, an instructive and delightful experience." In a further letter to Mill he outlined his wishes to go South again, adding: "the taste I have had has made me ravenous".

Within months he was making proposals for a scientific expedition to South Georgia, but the RGS would not support his plans. In early 1896 he considered collaboration with the Norwegians Henryk Bull

Henrik Johan Bull (13 October 18441 June 1930) was a Norwegian businessman and whaler. Henry Bull was one of the pioneers in the exploration of Antarctica.

Biography

Henrik Johan Bull was born at Stokke in Vestfold County, Norway. He attended sc ...

and Carsten Borchgrevink

Carsten Egeberg Borchgrevink (1 December 186421 April 1934) was an Anglo-Norwegian polar explorer and a pioneer of Antarctic travel. He inspired Sir Robert Falcon Scott, Sir Ernest Shackleton, Roald Amundsen, and others associated with the Hero ...

in an attempt to reach the South Magnetic Pole. This, too, failed to materialise.

Jackson–Harmsworth Expedition

From September 1895 to June 1896 Bruce worked at theBen Nevis

Ben Nevis ( ; gd, Beinn Nibheis ) is the highest mountain in Scotland, the United Kingdom and the British Isles. The summit is above sea level and is the highest land in any direction for . Ben Nevis stands at the western end of the Grampian ...

summit meteorological station, where he gained further experience in scientific procedures and with meteorological instruments. In June 1896, again on the recommendation of Mill, he left this post to join the Jackson–Harmsworth Expedition, then in its third year in the Arctic on Franz Josef Land

Franz Josef Land, Frantz Iosef Land, Franz Joseph Land or Francis Joseph's Land ( rus, Земля́ Фра́нца-Ио́сифа, r=Zemlya Frantsa-Iosifa, no, Fridtjof Nansen Land) is a Russian archipelago in the Arctic Ocean. It is inhabited on ...

. This expedition, led by Frederick George Jackson

Frederick George Jackson (6 March 1860 – 13 March 1938) was an English Arctic explorer remembered for his expedition to Franz Josef Land, when he located the missing Norwegian explorer Fridtjof Nansen.

Biography

Early life

Jackson wa ...

and financed by newspaper magnate Alfred Harmsworth

Alfred Charles William Harmsworth, 1st Viscount Northcliffe (15 July 1865 – 14 August 1922), was a British newspaper and publishing magnate. As owner of the ''Daily Mail'' and the ''Daily Mirror'', he was an early developer of popular journal ...

, had left London in 1894. It was engaged in a detailed survey of the Franz Josef archipelago

An archipelago ( ), sometimes called an island group or island chain, is a chain, cluster, or collection of islands, or sometimes a sea containing a small number of scattered islands.

Examples of archipelagos include: the Indonesian Arc ...

, which had been discovered, though not properly mapped, during an Austrian expedition 20 years earlier. Jackson's party was based at Cape Flora

Northbrook Island (russian: остров Нортбрук) is an island located in the southern edge of the Franz Josef Archipelago, Russia. Its highest point is 344 m above sea level.

Northbrook Island is one of the most accessible locations i ...

on Northbrook Island

Northbrook Island (russian: остров Нортбрук) is an island located in the southern edge of the Franz Josef Archipelago, Russia. Its highest point is 344 m above sea level.

Northbrook Island is one of the most accessible locations i ...

, the southernmost island of the archipelago. It was supplied through regular visits from its expedition ship ''Windward'', on which Bruce sailed from London on 9 June 1896.

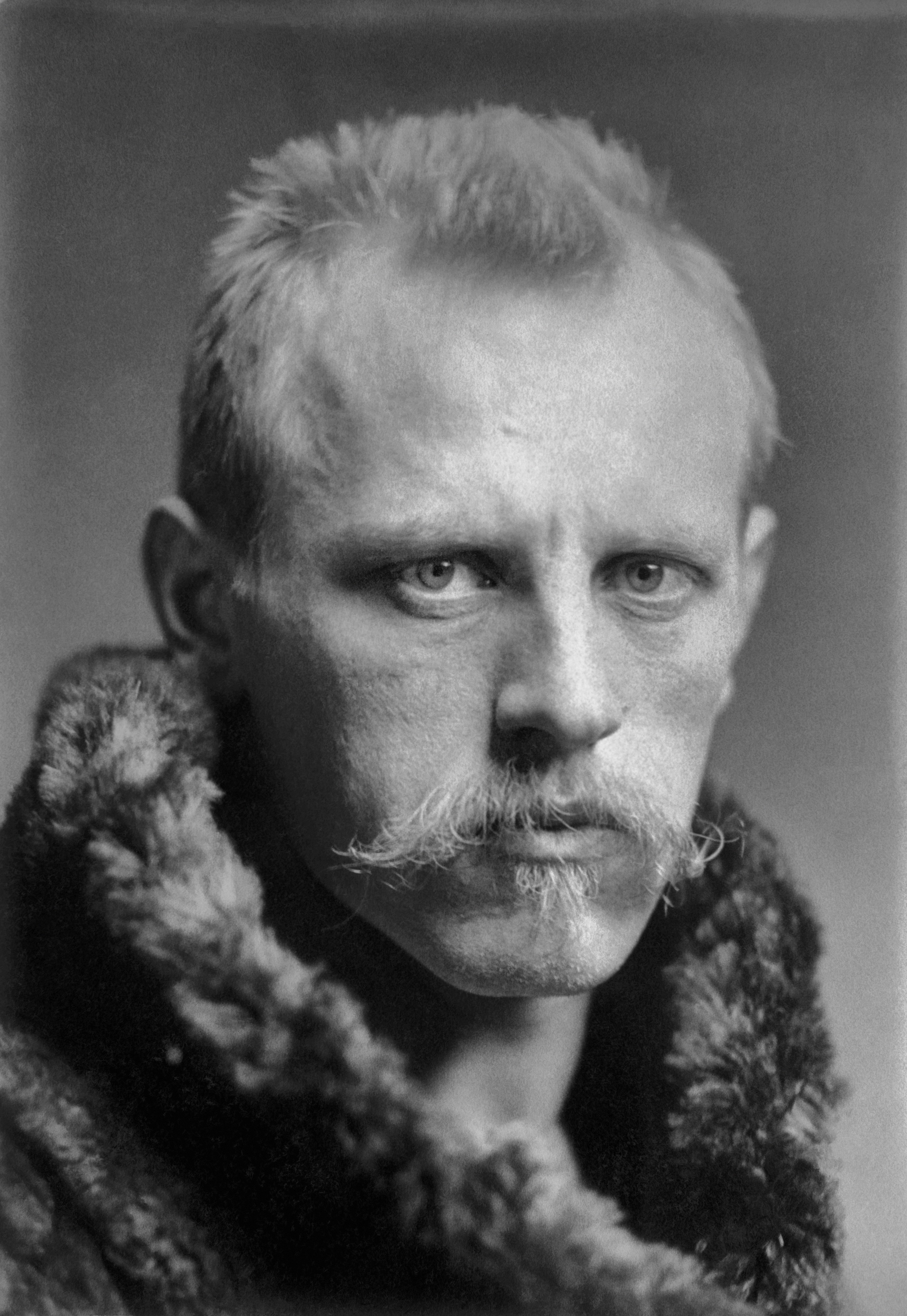

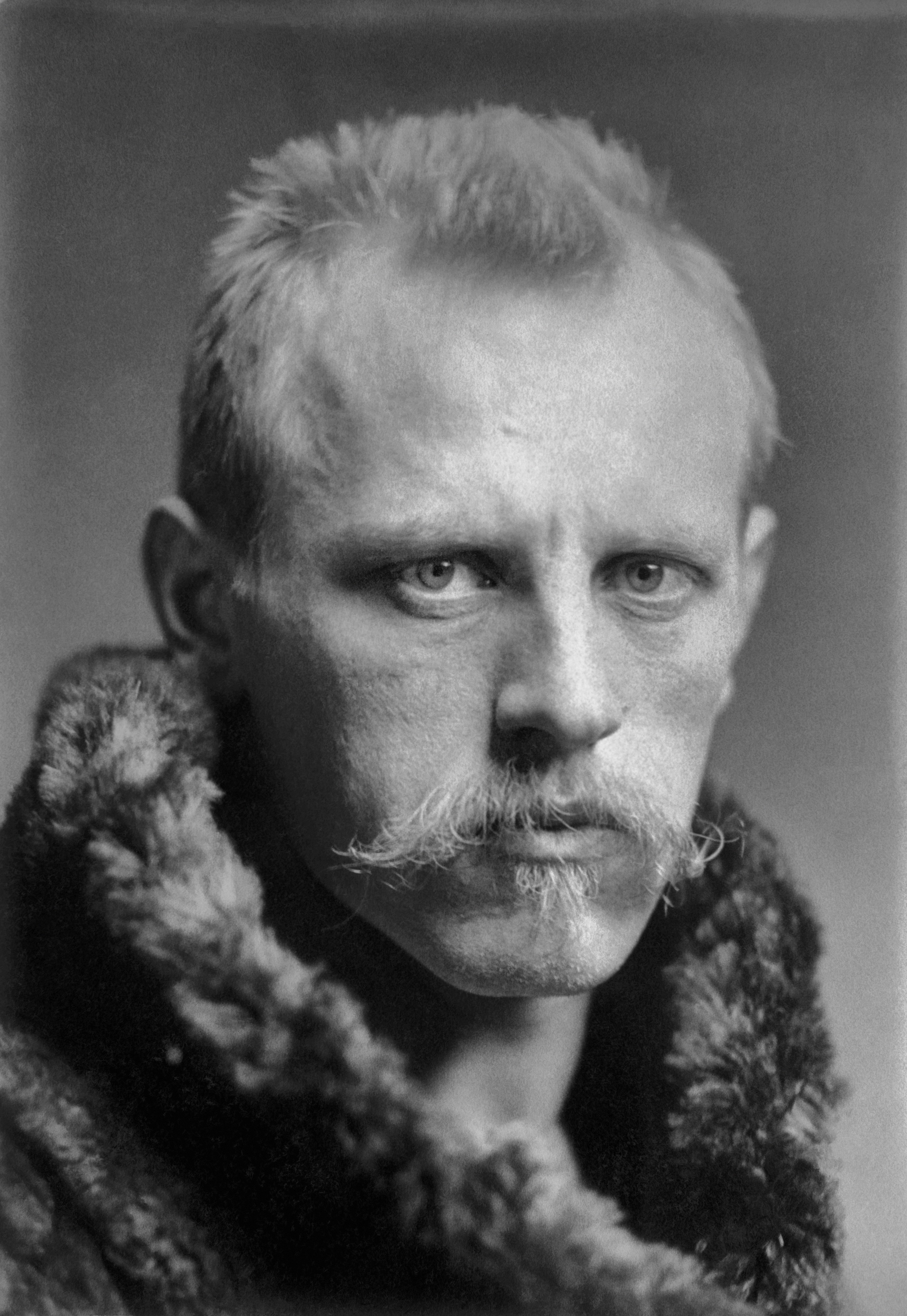

''Windward'' arrived at Cape Flora on 25 July where Bruce found that Jackson's expedition party had been joined by Fridtjof Nansen and his companion

''Windward'' arrived at Cape Flora on 25 July where Bruce found that Jackson's expedition party had been joined by Fridtjof Nansen and his companion Hjalmar Johansen

Fredrik Hjalmar Johansen (15 May 1867 – 3 January 1913) was a Norwegian polar explorer. He participated on the first and third '' Fram'' expeditions. He shipped out with the Fridtjof Nansen expedition in 1893–1896, and accompanied Nansen ...

. The two Norwegians had been living on the ice for more than a year since leaving their ship '' Fram'' for a dash to the North Pole, and it was pure chance that had brought them to the one inhabited spot among thousands of square miles of Arctic wastes. Bruce mentions meeting Nansen in a letter to Mill, and his acquaintance with the celebrated Norwegian would be a future source of much advice and encouragement.

During his year at Cape Flora Bruce collected around 700 zoological specimens, in often very disagreeable conditions. According to Jackson: "It is no pleasant job to dabble in icy-cold water, with the thermometer some degrees below zero, or to plod in the summer through snow, slush and mud many miles in search of animal life, as I have known Mr Bruce frequently to do". Jackson named Cape Bruce

Cape Bruce forms the northern tip of a small island lying at the eastern side of Oom Bay, separated from the mainland rocks just west of Taylor Glacier in Mac. Robertson Land, Antarctica.

Historic site

A landing was made at the cape on 18 Februar ...

after him, on the northern edge of Northbrook Island, at 80°55′N. Jackson was less pleased with Bruce's proprietorial attitude to his personal specimens, which he refused to entrust to the British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

with the expedition's other finds. This "tendency towards scientific conceit", and lack of tact in interpersonal dealings, were early demonstrations of character flaws that in later life would be held against him.

Arctic voyages

On his return from Franz Josef Land in 1897, Bruce worked in Edinburgh as an assistant to his former mentor John Arthur Thomson, and resumed his duties at the Ben Nevis observatory. In March 1898 he received an offer to join Major Andrew Coats on a hunting voyage to the Arctic waters around Novaya Zemlya and Spitsbergen, in the private yacht ''Blencathra''. This offer had originally been made to Mill, who was unable to obtain leave from the Royal Geographical Society, and once again suggested Bruce as a replacement. Andrew Coats was a member of the prosperous Coats family of thread manufacturers, who had founded the

On his return from Franz Josef Land in 1897, Bruce worked in Edinburgh as an assistant to his former mentor John Arthur Thomson, and resumed his duties at the Ben Nevis observatory. In March 1898 he received an offer to join Major Andrew Coats on a hunting voyage to the Arctic waters around Novaya Zemlya and Spitsbergen, in the private yacht ''Blencathra''. This offer had originally been made to Mill, who was unable to obtain leave from the Royal Geographical Society, and once again suggested Bruce as a replacement. Andrew Coats was a member of the prosperous Coats family of thread manufacturers, who had founded the Coats Observatory

Coats Observatory is Scotland's oldest public observatory. It is currently closed for refurbishment as part of a 4-year long £42m transformation of the observatory and museum buildings. Located in Oakshaw Street West, Paisley, Renfrewshire, the ...

at Paisley. Bruce joined ''Blencathra'' at Tromsø

Tromsø (, , ; se, Romsa ; fkv, Tromssa; sv, Tromsö) is a municipality in Troms og Finnmark county, Norway. The administrative centre of the municipality is the city of Tromsø.

Tromsø lies in Northern Norway. The municipality is the ...

, Norway in May 1898, for a cruise which explored the Barents Sea

The Barents Sea ( , also ; no, Barentshavet, ; russian: Баренцево море, Barentsevo More) is a marginal sea of the Arctic Ocean, located off the northern coasts of Norway and Russia and divided between Norwegian and Russian territo ...

, the dual islands of Novaya Zemlya, and the island of Kolguyev

Kolguyev Island (russian: о́стров Колгу́ев) is an island in Nenets Autonomous Okrug of Russia, located in the south-eastern Barents Sea (west of the Pechora Sea) to the north-east of the Kanin Peninsula.

Origin of the name

There ...

, before a retreat to Vardø

( fi, Vuoreija, fkv, Vuorea, se, Várggát) is a municipality in Troms og Finnmark county in the extreme northeastern part of Norway. Vardø is the easternmost town in Norway, more to the east than Saint Petersburg or Istanbul. The administr ...

in north-eastern Norway to re-provision for the voyage to Spitsbergen. In a letter to Mill, Bruce reported: "This is a pure yachting cruise and life is luxurious". But his scientific work was unabated: "I have been taking 4-hourly observations in meteorology and temperature of the sea surface ..have tested salinity with Buchanan's hydrometer; my tow-nets ..have been going almost constantly".

''Blencathra'' sailed for Spitsbergen, but was stopped by ice, so she returned to Tromsø. Here she encountered the research ship ''Princesse Alice'', purpose-built for Prince Albert I of Monaco

Albert I (Albert Honoré Charles Grimaldi; 13 November 1848 – 26 June 1922) was Prince of Monaco from 10 September 1889 until his death. He devoted much of his life to oceanography, exploration and science. Alongside his expeditions, Albert ...

, a leading oceanographer. Bruce was delighted when the Prince invited him to join ''Princesse Alice'' on a hydrographic survey around Spitsbergen. The ship sailed up the west coast of the main island of the Spitsbergen group, and visited Adventfjorden and Smeerenburg

Smeerenburg was a whaling settlement on Amsterdam Island in northwest Svalbard. It was founded by the Danish and Dutch in 1619 as one of Europe's northernmost outposts. With the local bowhead whale population soon decimated and whaling deve ...

in the north. During the latter stages of the voyage Bruce was placed in charge of the voyage's scientific observations.

The following year Bruce was invited to join Prince Albert on another oceanographic cruise to Spitsbergen. At Red Bay, latitude 80°N, Bruce ascended the highest peak in the area, which the prince named "Ben Nevis" in his honour. When ''Princesse Alice'' ran aground on a submerged rock and appeared stranded, Prince Albert instructed Bruce to begin preparations for a winter camp, in the belief that it might be impossible for the ship to escape. Fortunately she floated free, and was able to return to Tromsø for repairs.

Marriage and family life

It is uncertain how Bruce was employed after his return from Spitsbergen in late 1899. In his whole life he rarely had settled salaried work, and usually relied on patronage or on influential acquaintances to find him temporary posts. Early in 1901 he evidently felt sufficiently confident of his prospects to get married. His bride was Jessie Mackenzie, who had worked as a nurse in Samuel Bruce's London surgery. Bruce's marriage took place in the United Free Church of Scotland, in Chapelhill within the Parish of Nigg on 20 January 1901, being attended and witnessed by their parents. Perhaps, due to Bruce's secretive nature presenting limited details even among his circle of close friends and colleagues, little information about the wedding has been recorded by his biographers. In 1907 the Bruces settled in a house at South Morton Street in Joppa near the coastal Edinburgh suburb ofPortobello

Portobello, Porto Bello, Porto Belo, Portabello, or Portabella may refer to:

Places Brazil

* Porto Belo

Ireland

* Portobello, Dublin

* Cathal Brugha Barracks, Dublin formerly ''Portobello Barracks''

New Zealand

* Portobello, New Zealand, on Ot ...

, in the first of a series of addresses in that area. They named their house "Antarctica". A son, Eillium Alastair, was born in April 1902, and a daughter, Sheila Mackenzie, was born seven years later. During these years Bruce founded the Scottish Ski Club and became its first president. He was also a co-founder of Edinburgh Zoo

Edinburgh Zoo, formerly the Scottish National Zoological Park, is an non-profit zoological park in the Corstorphine area of Edinburgh, Scotland.

The land lies on the south facing slopes of Corstorphine Hill, from which it provides extensive v ...

.

Bruce's chosen life as an explorer, his unreliable sources of income and his frequent extended absences, all placed severe strains on the marriage, and the couple became estranged around 1916. They continued to live in the same house until Bruce's death. Eillium became a Merchant Navy officer, eventually captaining a Fisheries Research Ship which, by chance, bore the name ''Scotia''.

Scottish National Antarctic Expedition

Dispute with Markham

On 15 March 1899 Bruce wrote toSir Clements Markham

Sir Clements Robert Markham (20 July 1830 – 30 January 1916) was an English geographer, explorer and writer. He was secretary of the Royal Geographical Society (RGS) between 1863 and 1888, and later served as the Society's president for ...

at the RGS, offering himself for the scientific staff of the National Antarctic Expedition, then in its early planning stages. Markham's reply was a non-committal one-line acknowledgement, after which Bruce heard nothing for a year. He was then told, indirectly, to apply for a scientific assistant's post.

On 21 March 1900 Bruce reminded Markham that he had applied a year earlier, and went on to reveal that he "was not without hopes of being able to raise sufficient capital whereby I could take out a second British ship". He followed this up a few days later, and reported that the funding for a second ship was now assured, making his first explicit references to a "Scottish Expedition". This alarmed Markham, who replied with some anger: "Such a course will be most prejudicial to the Expedition ..A second ship is not in the least required ..I do not know why this mischievous rivalry should have been started".

Bruce replied by return, denying rivalry, and asserting: "If my friends are prepared to give me money to carry out my plans I do not see why I should not accept it ..there are several who maintain that a second ship is highly desirable". Unappeased, Markham wrote back: "As I was doing my best to get you appointed (to the National Antarctic Expedition) I had a right to think you would not take such a step ..without at least consulting me". He continued: "You will cripple the National Expedition ..in order to get up a scheme for yourself".

Bruce replied formally, saying that the funds he had raised in Scotland would not have been forthcoming for any other project. There was no further correspondence between the two, beyond a short conciliatory note from Markham, in February 1901, which read "I can now see things from your point of view, and wish you success"—a sentiment apparently not reflected in Markham's subsequent attitude towards the Scottish expedition.

Voyage of the ''Scotia''

With financial support from the Coats family, Bruce had acquired a

With financial support from the Coats family, Bruce had acquired a Norwegian

Norwegian, Norwayan, or Norsk may refer to:

*Something of, from, or related to Norway, a country in northwestern Europe

* Norwegians, both a nation and an ethnic group native to Norway

* Demographics of Norway

*The Norwegian language, including ...

whaler

A whaler or whaling ship is a specialized vessel, designed or adapted for whaling: the catching or processing of whales.

Terminology

The term ''whaler'' is mostly historic. A handful of nations continue with industrial whaling, and one, Japa ...

, , which he transformed into a fully equipped Antarctic research ship, renamed ''Scotia''. He then appointed an all-Scottish crew and scientific team. ''Scotia'' left Troon

Troon is a town in South Ayrshire, situated on the west coast of Ayrshire in Scotland, about north of Ayr and northwest of Glasgow Prestwick Airport.

Troon has a port with freight services and a yacht marina. Up until January 2016, P&O ope ...

on 2 November 1902, and headed south towards Antarctica, where Bruce intended to set up winter quarters in the Weddell Sea quadrant, "as near to the South Pole as is practicable". On 22 February the ship reached 70°25′S, but could proceed no further because of heavy ice. She retreated to Laurie Island

Laurie Island is the second largest of the South Orkney Islands. The island is claimed by both Argentina as part of Argentine Antarctica, and the United Kingdom as part of the British Antarctic Territory. However, under the Antarctic Treaty ...

in the South Orkneys

The South Orkney Islands are a group of islands in the Southern Ocean, about north-east of the tip of the Antarctic Peninsulameteorological station

A weather station is a facility, either on land or sea, with instruments and equipment for measuring atmospheric conditions to provide information for weather forecasts and to study the weather and climate. The measurements taken include tempera ...

, Omond House (named after Robert Traill Omond), was established as part of a full programme of scientific work.

In November 1903 ''Scotia'' retreated to Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires ( or ; ), officially the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires ( es, link=no, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires), is the capital and primate city of Argentina. The city is located on the western shore of the Río de la Plata, on South ...

for repair and reprovisioning. While in Argentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the second-largest country in South America after Brazil, th ...

, Bruce negotiated an agreement with the government whereby Omond House became a permanent weather station, under Argentinian control. Renamed Orcadas Base )

, subdivision_type4 = Location

, subdivision_name4 = Laurie Island

, established_title1 = Established

, established_date1 = 1903

, established_title2 = Founded

, established_date2 =

, elevation_m ...

, the site has been continuously in operation since then, and provides the longest historical meteorological series of Antarctica. In January 1904 ''Scotia'' sailed south again, to explore the Weddell Sea. On 6 March, new land was sighted, part of the sea's eastern boundary; Bruce named this Coats Land

Coats Land is a region in Antarctica which lies westward of Queen Maud Land and forms the eastern shore of the Weddell Sea, extending in a general northeast–southwest direction between 20°00′W and 36°00′W. The northeast part was discove ...

after the expedition's chief backers. On 14 March, at 74°01′S and in danger of becoming icebound, Scotia turned north. The long voyage back to Scotland, via Cape Town

Cape Town ( af, Kaapstad; , xh, iKapa) is one of South Africa's three capital cities, serving as the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. It is the legislative capital of the country, the oldest city in the country, and the second largest ...

, was completed on 21 July 1904.

This expedition assembled a large collection of animal, marine and plant specimens, and carried out extensive hydrographic, magnetic and meteorological observations. One hundred years later it was recognised that the expedition's work had "laid the foundation of modern climate change studies", and that its experimental work had showed this part of the globe to be crucially important to the world's climate. According to the oceanographer Tony Rice, it fulfilled a more comprehensive programme than any other Antarctic expedition of its day. At the time its reception in Britain was relatively muted; although its work was highly praised within sections of the scientific community, Bruce struggled to raise the funding to publish his scientific results, and blamed Markham for the lack of national recognition.

Post-expedition years

Scottish Oceanographical Laboratory

Bruce's collection of specimens, gathered from more than a decade of Arctic and Antarctic travel, required a permanent home. Bruce himself needed a base from which the detailed scientific reports of the ''Scotia'' voyage could be prepared for publication. He obtained premises in Nicolson Street, Edinburgh, in which he established a laboratory and museum, naming it theScottish Oceanographical Laboratory

The Scottish Oceanographical Laboratory was founded in Nicolson Street, Edinburgh in 1906, by William Speirs Bruce, who had travelled widely in the Antarctic and Arctic regions and had led the Scottish National Antarctic Expedition (SNAE) 1902&nda ...

, with the ultimate ambition that it should become the Scottish National Oceanographic Institute. It was officially opened by Prince Albert of Monaco in 1906.

Within these premises Bruce housed his meteorological and oceanographic equipment, in preparation for future expeditions. He also met there with fellow-explorers, including Nansen, Shackleton, and Roald Amundsen

Roald Engelbregt Gravning Amundsen (, ; ; 16 July 1872 – ) was a Norwegian explorer of polar regions. He was a key figure of the period known as the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration.

Born in Borge, Østfold, Norway, Amundsen beg ...

. His main task was masterminding the preparation of the SNAE scientific reports. These, at considerable cost and much delay, were published between 1907 and 1920, except for one volume—Bruce's own log—that remained unpublished until 1992, after its rediscovery. Bruce maintained a wide correspondence with experts, including Sir Joseph Hooker, who had travelled to the Antarctic with James Clark Ross

Sir James Clark Ross (15 April 1800 – 3 April 1862) was a British Royal Navy officer and polar explorer known for his explorations of the Arctic, participating in two expeditions led by his uncle John Ross, and four led by William Edwa ...

in 1839–43, and to whom Bruce dedicated his short book ''Polar Exploration''.

In 1914 discussions began toward finding more permanent homes, both for Bruce's collection and, following the death that year of oceanographer Sir John Murray, for the specimens and library of the Challenger expedition. Bruce proposed that a new centre should be created as a memorial to Murray. There was unanimous agreement to proceed, but the project was curtailed by the outbreak of war, and not revived. The Scottish Oceanographical Laboratory continued until 1919, when Bruce, in poor health, was forced to close it, dispersing its contents to the Royal Scottish Museum

The National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh, Scotland, was formed in 2006 with the merger of the new Museum of Scotland, with collections relating to Scottish antiquities, culture and history, and the adjacent Royal Scottish Museum (opened in ...

, the Royal Scottish Geographical Society

The Royal Scottish Geographical Society (RSGS) is an educational charity based in Perth, Scotland founded in 1884. The purpose of the society is to advance the subject of geography worldwide, inspire people to learn more about the world around ...

(RSGS), and the University of Edinburgh.

Further Antarctic plans

On 17 March 1910 Bruce presented proposals to the Royal Scottish Geographical Society (RSGS) for a new Scottish Antarctic expedition. His plan envisaged a party wintering in or near Coats Land, while the ship took another group to theRoss Sea

The Ross Sea is a deep bay of the Southern Ocean in Antarctica, between Victoria Land and Marie Byrd Land and within the Ross Embayment, and is the southernmost sea on Earth. It derives its name from the British explorer James Clark Ross who ...

, on the opposite side of the continent. During the second season the Coats Land party would cross the continent on foot, via the South Pole

The South Pole, also known as the Geographic South Pole, Terrestrial South Pole or 90th Parallel South, is one of the two points where Earth's axis of rotation intersects its surface. It is the southernmost point on Earth and lies antipod ...

, while the Ross Sea party pushed south to meet them and assist them home. The expedition would also carry out extensive oceanographical and other scientific work. Bruce estimated that the total cost would be about £50,000 ( value about £).

The RSGS supported these proposals, as did the Royal Society of Edinburgh, the University of Edinburgh, and other Scottish organisations, but the timing was wrong; the Royal Geographical Society in London was fully occupied with Robert Scott's Terra Nova Expedition

The ''Terra Nova'' Expedition, officially the British Antarctic Expedition, was an expedition to Antarctica which took place between 1910 and 1913. Led by Captain Robert Falcon Scott, the expedition had various scientific and geographical objec ...

, and showed no interest in Bruce's plans. No rich private benefactors came forward, and persistent and intensive lobbying of the government for financial backing failed. Bruce suspected that his efforts were, as usual, being undermined by the aged but still influential Markham. Finally accepting that his venture would not take place, he gave generous support and advice to Ernest Shackleton, who in 1913 announced plans, similar to Bruce's, for his Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition

The Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition of 1914–1917 is considered to be the last major expedition of the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration. Conceived by Sir Ernest Shackleton, the expedition was an attempt to make the first land crossing ...

. Shackleton not only received £10,000 from the government, but raised large sums from private sources, including £24,000 from Scottish industrialist Sir James Caird of Dundee.

Shackleton's expedition was an epic adventure, but failed completely in its main endeavour of a transcontinental crossing. Bruce was not consulted by the Shackleton relief committee about that expedition's rescue, when the need arose in 1916. "Myself, I suppose," he wrote, "because of being north of the Tweed, they think dead".

Scottish Spitsbergen syndicate

During his Spitsbergen visits with Prince Albert in 1898 and 1899, Bruce had detected the presence of coal,

During his Spitsbergen visits with Prince Albert in 1898 and 1899, Bruce had detected the presence of coal, gypsum

Gypsum is a soft sulfate mineral composed of calcium sulfate dihydrate, with the chemical formula . It is widely mined and is used as a fertilizer and as the main constituent in many forms of plaster, blackboard or sidewalk chalk, and drywal ...

and possibly oil. In the summers of 1906 and 1907 he again accompanied the Prince to the archipelago, with the primary purpose of surveying and mapping Prince Charles Foreland

Prins Karls Forland or Forlandet, occasionally anglicized as Prince Charles Foreland, is an island off the west coast of Oscar II Land on Spitsbergen in the Arctic archipelago of Svalbard, Norway. The entire island and the surrounding sea area ...

, an island unvisited during the earlier voyages. Here Bruce found further deposits of coal, and indications of iron. On the basis of these finds, Bruce set up a mineral prospecting company, the Scottish Spitsbergen Syndicate, in July 1909.

At that time, in international law Spitsbergen was regarded as ''terra nullius

''Terra nullius'' (, plural ''terrae nullius'') is a Latin expression meaning " nobody's land".

It was a principle sometimes used in international law to justify claims that territory may be acquired by a state's occupation of it.

:

:

...

''—rights to mine and extract could be established simply by registering a claim. Bruce's syndicate registered claims on Prince Charles Foreland and on the islands of Barentsøya

Barentsøya, sometimes anglicized as Barents Island, is an island in the Svalbard archipelago of Norway, lying between Edgeøya and Spitsbergen. Barents Island has no permanent human inhabitants. Named for the Dutch explorer Willem Barents (who ...

and Edgeøya

Edgeøya (), occasionally anglicised as Edge Island, is a Norwegian island located in southeast of the Svalbard archipelago; with an area of , it is the third-largest island in this archipelago. An Arctic island, it forms part of the Søraust-S ...

, among other areas. A sum of £4,000 (out of a target of £6,000) was subscribed to finance the costs of a detailed prospecting expedition in 1909, in a chartered vessel with a full scientific team. The results were "disappointing", and the voyage absorbed almost all of the syndicate's funds.

Bruce paid two further visits to Spitsbergen, in 1912 and 1914, but the outbreak of war prevented further immediate developments. Early in 1919 the old syndicate was replaced by a larger and better-financed company. Bruce had now fixed his main hopes on the discovery of oil, but scientific expeditions in 1919 and 1920 failed to provide evidence of its presence; substantial new deposits of coal and iron ore were discovered. Thereafter Bruce was too ill to continue with his involvement. The new company had expended most of its capital on these prospecting ventures, and although it continued to exist, under various ownerships, until 1952, there is no record of profitable extraction. Its assets and claims were finally acquired by a rival concern.

Later life

Polar Medals withheld

During his lifetime Bruce received many awards: theGold Medal of the Royal Scottish Geographical Society

The Scottish Geographical Medal is the highest accolade of the Royal Scottish Geographical Society

The Royal Scottish Geographical Society (RSGS) is an educational charity based in Perth, Scotland founded in 1884. The purpose of the society i ...

in 1904; the Patron's Medal of the Royal Geographical Society in 1910; the Neill prize and Medal of the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1913, and the Livingstone Medal of the American Geographical Society

The American Geographical Society (AGS) is an organization of professional geographers, founded in 1851 in New York City. Most fellows of the society are Americans, but among them have always been a significant number of fellows from around the ...

in 1920. He also received an honorary LLD degree from the University of Aberdeen

, mottoeng = The fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom

, established =

, type = Public research universityAncient university

, endowment = £58.4 million (2021)

, budget ...

. The honour that eluded him was the Polar Medal, awarded by the Sovereign on the recommendation of the Royal Geographical Society. The Medal was awarded to the members of every other British or Commonwealth Antarctic expedition during the early 20th century, but the SNAE was the exception; the medal was withheld.

Bruce, and those close to him, blamed Markham for this omission. The matter was raised, repeatedly, with anyone thought to have influence. Robert Rudmose Brown, chronicler of the ''Scotia'' voyage and later Bruce's first biographer, wrote in a 1913 letter to the President of the Royal Scottish Geographical Society that this neglect was "a slight to Scotland and to Scottish endeavour". Bruce wrote in March 1915 to the President of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, who agreed in his reply that "Markham had much to answer for". After Markham's death in 1916 Bruce sent a long letter to his Member of Parliament, Charles Price, detailing Sir Clements's malice towards him and the Scottish expedition, ending with a heartfelt cry on behalf of his old comrades: "Robertson is dying without his well won white ribbon! The Mate is dead!! The Chief Engineer is dead!!! Everyone as good men as have ever served on any Polar Expedition, yet they did not receive the white ribbon." No action followed this plea.

No award had been made nearly a century later, when the matter was raised in the Scottish Parliament. On 4 November 2002 MSP Michael Russell tabled a motion relating to the SNAE centenary, which concluded: "The Polar Medal Advisory Committee should recommend the posthumous award of the Polar Medal to Dr William Speirs Bruce, in recognition of his status as one of the key figures in early 20th century polar scientific exploration".

Last years

After the outbreak of war in 1914, Bruce's prospecting ventures were on hold. He offered his services to theAdmiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

*Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Traf ...

, but failed to obtain an appointment. In 1915 he accepted a post as director and manager of a whaling company based in the Seychelles

Seychelles (, ; ), officially the Republic of Seychelles (french: link=no, République des Seychelles; Creole: ''La Repiblik Sesel''), is an archipelagic state consisting of 115 islands in the Indian Ocean. Its capital and largest city, ...

, and spent four months there, but the venture failed. On his return to Britain he finally secured a minor post at the Admiralty.

Bruce continued to lobby for recognition, highlighting the distinctions between the treatment of SNAE and that of English expeditions. When the war finished he attempted to revive his various interests, but his health was failing, forcing him to close his laboratory. On the 1920 voyage to Spitsbergen he travelled in an advisory role, unable to participate in the detailed work. On return, he was confined in the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary

The Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh, or RIE, often (but incorrectly) known as the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary, or ERI, was established in 1729 and is the oldest voluntary hospital in Scotland. The new buildings of 1879 were claimed to be the largest v ...

and later in the Liberton Hospital

Liberton Hospital is a facility for geriatric medicine on Lasswade Road in Edinburgh, Scotland. It is managed by NHS Lothian.

History

The hospital, which was designed by John Dick Peddie and George Washington Browne opened in 1906. It operated in ...

, Edinburgh, where he died on 28 October 1921. In accordance with his wishes he was cremated, and the ashes taken to South Georgia to be scattered on the southern sea. Despite his irregular income and general lack of funds, his estate realised £7,000 ( value about £).

Assessment

After Bruce's death his long-time friend and colleague Robert Rudmose Brown wrote, in a letter to Bruce's father: "His name is imperishably enrolled among the world's great explorers, and the martyrs to unselfish scientific devotion." Rudmose Brown's biography was published in 1923, and in the same year a joint committee of Edinburgh's learned societies instituted the Bruce Memorial Prize, an award for young polar scientists. Thereafter his name continued to be respected in scientific circles, but Bruce and his achievements were forgotten by the general public. Occasional mentions of him, in polar histories and biographies of major figures such as Scott and Shackleton, tended to be dismissive and inaccurate. The early years of the 21st century have seen a reassessment of Bruce's work. Contributory factors have been the SNAE centenary, and Scotland's renewed sense of national identity. A 2003 expedition, in a modern research ship "Scotia", used information collected by Bruce as a basis for examining climate change in South Georgia. This expedition predicted "dramatic conclusions" relating to global warming from its research, and saw this contribution as a "fitting tribute to Britain's forgotten polar hero, William Speirs Bruce".

An hour-long BBC television documentary on Bruce presented by

The early years of the 21st century have seen a reassessment of Bruce's work. Contributory factors have been the SNAE centenary, and Scotland's renewed sense of national identity. A 2003 expedition, in a modern research ship "Scotia", used information collected by Bruce as a basis for examining climate change in South Georgia. This expedition predicted "dramatic conclusions" relating to global warming from its research, and saw this contribution as a "fitting tribute to Britain's forgotten polar hero, William Speirs Bruce".

An hour-long BBC television documentary on Bruce presented by Neil Oliver

Neil Oliver (born 21 February 1967) is a British television presenter, archaeologist, historian and author. He has presented several documentary series on archaeology and history, including ''A History of Scotland'', ''Vikings'', and ''Coast'' ...

in 2011 contrasted his meticulous science with his rivals' aim of enhancing imperial prestige./ref> A new biographer, Peter Speak (2003), claims that the SNAE was "by far the most cost-effective and carefully planned scientific expedition of the Heroic Age". The same author considers reasons why Bruce's efforts to capitalise on this success met with failure, and suggests a combination of his shy, solitary, uncharismatic nature and his "fervent" Scottish nationalism. Bruce seemingly lacked public relations skills and the ability to promote his work, after the fashion of Scott and Shackleton; a lifelong friend described him as being "as prickly as the Scottish thistle itself". On occasion he behaved tactlessly, as with Jackson over the question of the specimens brought back from

Franz Josef Land

Franz Josef Land, Frantz Iosef Land, Franz Joseph Land or Francis Joseph's Land ( rus, Земля́ Фра́нца-Ио́сифа, r=Zemlya Frantsa-Iosifa, no, Fridtjof Nansen Land) is a Russian archipelago in the Arctic Ocean. It is inhabited on ...

, and on another occasion with the Royal Geographical Society, over the question of a minor expense claim.

As to his nationalism, he wished to see Scotland on an equal footing with other nations. His national pride was intense; in a Preparatory Note to ''The Voyage of the Scotia'' he wrote: "While 'Science' was the talisman of the Expedition, 'Scotland' was emblazoned on its flag". This insistence on emphasising the Scottish character of his enterprises could be irksome to those who did not share his passion. He retained the respect and devotion of those whom he led, and of those who had known him longest. John Arthur Thomson, who had known Bruce since Granton, wrote of him when reviewing Rudmose Brown's 1923 biography

A biography, or simply bio, is a detailed description of a person's life. It involves more than just the basic facts like education, work, relationships, and death; it portrays a person's experience of these life events. Unlike a profile or ...

: "We never heard him once grumble about himself, though he was neither to hold or bend when he thought some injustice was being done to, or slight cast on, his men, on his colleagues, on his laboratory, on his Scotland. Then one got glimpses of the volcano which his gentle spirit usually kept sleeping."

See also

*List of recipients of the W. S. Bruce Medal

This is a list of recipients of the W. S. Bruce Medal.

Established in 1923, the medal is awarded quinquennially for notable contributions to "Zoology, Botany, Geology, Meteorology, Oceanography or Geography, where new knowledge has been gained th ...

Notes and references

CitationsSources

* * * * * * * * * Online sources * * * * *External links

* *William Speirs Bruce Collection at the University of Edinburgh

Retrieved 2017-09-11 {{DEFAULTSORT:Bruce, William 19th-century biologists 19th-century explorers 19th-century Scottish people 1867 births 1921 deaths Academics of Heriot-Watt University Alumni of the University of Edinburgh Explorers of Antarctica Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh People educated at University College School People educated at Watts Naval School People from Kensington Scottish marine biologists Scottish nationalists Scottish naturalists Scottish oceanographers Scottish people of Welsh descent Scottish polar explorers