William Fessenden on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

William Pitt Fessenden (October 16, 1806September 8, 1869) was an

Fessenden's strong anti-slavery principles caused his election to the U.S. Senate in 1854, with the support of Whigs and Anti-Slavery Democrats.

Upon taking office, he immediately began speaking against the

Fessenden's strong anti-slavery principles caused his election to the U.S. Senate in 1854, with the support of Whigs and Anti-Slavery Democrats.

Upon taking office, he immediately began speaking against the

Fessenden began his service as Secretary of the Treasury on July 5, 1864. The financial situation becoming favorable on the raising of another large loan, in accordance with his expressed intention, he resigned the secretaryship, leaving on March 3, 1865, to return to the Senate, to which he had now for the third time been elected, and where he would serve for the rest of his life.

From 1865 to 1867, he headed the Joint Committee on Reconstruction, which was responsible for overseeing the readmission of states from the former Confederacy into the Union. He wrote its report, which vindicated the power of Congress over the rebellious states, showed their relations to the government under the constitution and the law of nations, and recommended the constitutional safeguards made necessary by the rebellion. At this point, Fessenden was the acknowledged leader in the Senate among Republicans and was considered a moderate rather than Radical Republican. Radical leader

Fessenden began his service as Secretary of the Treasury on July 5, 1864. The financial situation becoming favorable on the raising of another large loan, in accordance with his expressed intention, he resigned the secretaryship, leaving on March 3, 1865, to return to the Senate, to which he had now for the third time been elected, and where he would serve for the rest of his life.

From 1865 to 1867, he headed the Joint Committee on Reconstruction, which was responsible for overseeing the readmission of states from the former Confederacy into the Union. He wrote its report, which vindicated the power of Congress over the rebellious states, showed their relations to the government under the constitution and the law of nations, and recommended the constitutional safeguards made necessary by the rebellion. At this point, Fessenden was the acknowledged leader in the Senate among Republicans and was considered a moderate rather than Radical Republican. Radical leader  During President Andrew Johnson's

During President Andrew Johnson's

Civil War Senator: William Pitt Fessenden and the Fight to Save the American Republic

' (Louisiana State University Press; 2011) 344 pages; a standard scholarly biography * Fessenden, Francis. ''Life and Public Services of William Pitt Fessenden: United States Senator from Maine 1854-1864; Secretary of the Treasury 1864-1865; United States Senator from Maine 1865-1869'' (1907

online

* Jellison, Charles.

Fessenden of Maine, Civil War Senator

' (1962), a standard scholarly biography * Landis, Michael Todd. "'A Champion Had Come': William Pitt Fessenden and the Republican Party, 1854–60," ''American Nineteenth Century History,'' Sept 2008, Vol. 9 Issue 3, pp. 269–285 * Richardson, Heather Cox. ''The Greatest Nation of the Earth: Republican Economic Policies during the Civil War'' (1997)

Guide to Research Collections

' where his papers are located.

Biography at Lincoln's White House

, - , - , - , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Fessenden, William P. 1806 births 1869 deaths 19th-century American politicians 19th-century American Episcopalians Republican Party members of the Maine House of Representatives United States Secretaries of the Treasury People of Maine in the American Civil War Union (American Civil War) political leaders Bowdoin College alumni Fessenden family Politicians from Portland, Maine People from Boscawen, New Hampshire Maine Oppositionists Republican Party United States senators from Maine Lincoln administration cabinet members Whig Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Maine Radical Republicans Moderate Republicans (Reconstruction era)

American politician

The politics of the United States function within a framework of a constitutional federal republic and presidential system, with three distinct branches that share powers. These are: the U.S. Congress which forms the legislative branch, a bi ...

from the U.S. state of Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and ...

. Fessenden was a Whig (later a Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

) and member of the Fessenden political family. He served in the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

and Senate before becoming Secretary of the Treasury

The United States secretary of the treasury is the head of the United States Department of the Treasury, and is the chief financial officer of the federal government of the United States. The secretary of the treasury serves as the principal a ...

under President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

. Fessenden then re-entered the Senate, where he died in office in 1869.

A lawyer, he was a leading antislavery Whig in Maine; in Congress, he fought the Slave Power, plantation owners who controlled Southern states. He built an antislavery coalition in the state legislature that elected him to the U.S. Senate; it became Maine's Republican organization. In the Senate, Fessenden played a central role in the debates on Kansas, denouncing the expansion of slavery. He led Radical Republicans

The Radical Republicans (later also known as "Stalwarts") were a faction within the Republican Party, originating from the party's founding in 1854, some 6 years before the Civil War, until the Compromise of 1877, which effectively ended Recons ...

in attacking Democrats Stephen Douglas

Stephen Arnold Douglas (April 23, 1813 – June 3, 1861) was an American politician and lawyer from Illinois. A senator, he was one of two nominees of the badly split Democratic Party for president in the 1860 presidential election, which wa ...

, Franklin Pierce, and James Buchanan. Fessenden's speeches were read widely, influencing Republicans such as Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

and building support for Lincoln's 1860 Republican presidential nomination. During the war, Senator Fessenden helped shape the Union's taxation and financial policies. He abandoned his earlier radicalism, joining pro-Lincoln Moderate Republicans against the RadicalsFoner, Eric (1988). ''Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877'', pp. 239–41. New York: Harper & Row. and becoming Lincoln's Treasury Secretary.

After the war, Fessenden was back in the Senate, as chair of the Joint Committee on Reconstruction, which established terms for resuming congressional representation for the southern states, and which drafted the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. Later, during the 1868 impeachment trial of President Andrew Johnson, Fessenden provided critical support that prevented the Senate conviction of President Johnson, who had been impeached by the House. He was the first Republican senator to ring out "...''not guilty''" followed by six other Republican senators, ultimately resulting in the acquittal of President Johnson. Fessenden's vote against convicting Johnson were motivated by his support for free trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. It can also be understood as the free market idea applied to international trade. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold econ ...

and fears of a Benjamin Wade

Benjamin Franklin "Bluff" Wade (October 27, 1800March 2, 1878) was an American lawyer and politician who served as a United States Senator for Ohio from 1851 to 1869. He is known for his leading role among the Radical Republicans.

presidency.''Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution'', p. 336.

He is the only person to have three streets in Portland named for him: William, Pitt and Fessenden streets in the city's Oakdale neighborhood.

Youth and early career

Fessenden was born inBoscawen, New Hampshire

Boscawen is a town in Merrimack County, New Hampshire, United States. The population was 3,998 at the 2020 census.

History

The native Pennacook people called the area ''Contoocook'', meaning "place of the river near pines". In March 1697, Hannah ...

on October 16, 1806. His father was attorney and legislator Samuel Fessenden

Samuel Fessenden (July 16, 1784 – March 13, 1869) was an American attorney, abolitionist, and politician. He served in both houses of the Massachusetts state legislature before Maine became a separate state. He was elected as major general i ...

. His mother was Ruth Greene. The parents were unmarried. William was separated from his mother at his birth, and he raised by his paternal grandmother for seven years.

He graduated from Bowdoin College in 1823 and then studied law. He was a founding member of the Maine Temperance Society in 1827. That year he was admitted to the bar, and practiced with his father, who was also a prominent anti-slavery activist. He practiced law first in Bridgton, Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and ...

, a year in Bangor, and afterward in Portland

Portland most commonly refers to:

* Portland, Oregon, the largest city in the state of Oregon, in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States

* Portland, Maine, the largest city in the state of Maine, in the New England region of the northeas ...

.

He was a member of the Maine House of Representatives in 1832 and was its leading debater. He refused nominations to Congress in 1831 and in 1838, and served in the Maine legislature again in 1840, becoming chairman of the house committee to revise the statutes of the state.

He was elected for one term in the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

as a Whig in 1840. During this term, he moved to repeal the rule that excluded anti-slavery petitions and spoke upon the loan and bankrupt bills, and the army. At the end of his term in Congress, he turned his attention wholly to his law business until he was again in the Maine legislature in 1845–46. He acquired a national reputation as a lawyer and an anti-slavery Whig, and in 1849 prosecuted before the United States Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

an appeal from an adverse decision of Judge Joseph Story

Joseph Story (September 18, 1779 – September 10, 1845) was an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, serving from 1812 to 1845. He is most remembered for his opinions in ''Martin v. Hunter's Lessee'' and '' United States ...

, and gained a reversal by an argument which Daniel Webster

Daniel Webster (January 18, 1782 – October 24, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented New Hampshire and Massachusetts in the U.S. Congress and served as the U.S. Secretary of State under Presidents William Henry Harrison ...

pronounced the best he had heard in twenty years. He was again in the Maine legislature in 1853 and 1854.

Service in U.S. Senate and Cabinet

Fessenden's strong anti-slavery principles caused his election to the U.S. Senate in 1854, with the support of Whigs and Anti-Slavery Democrats.

Upon taking office, he immediately began speaking against the

Fessenden's strong anti-slavery principles caused his election to the U.S. Senate in 1854, with the support of Whigs and Anti-Slavery Democrats.

Upon taking office, he immediately began speaking against the Kansas–Nebraska Act

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 () was a territorial organic act that created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska. It was drafted by Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas, passed by the 33rd United States Congress, and signed into law by ...

. His speech on the Clayton–Bulwer Treaty

The Clayton–Bulwer Treaty was a treaty signed in 1850 between the United States and the United Kingdom. The treaty was negotiated by John M. Clayton and Sir Henry Bulwer, amidst growing tensions between the two nations over Central America, a ...

, in 1856, received the highest praise, and in 1858 his speech on the Lecompton Constitution

The Lecompton Constitution (1859) was the second of four proposed constitutions for the state of Kansas. Named for the city of Lecompton where it was drafted, it was strongly pro-slavery. It never went into effect.

History Purpose

The Lecompton C ...

of Kansas, and his criticisms of the opinion of the supreme court in the Dred Scott case

''Dred Scott v. Sandford'', 60 U.S. (19 How.) 393 (1857), was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court that held the U.S. Constitution did not extend American citizenship to people of black African descent, enslaved or free; t ...

, were considered the ablest discussion of those topics. He participated in the organization of the Republican Party, being re-elected to the Senate from that group in 1860, this time without the formality of a nomination.

In 1861, he was a member of the Peace Congress

A peace congress, in international relations, has at times been defined in a way that would distinguish it from a peace conference (usually defined as a diplomatic meeting to decide on a peace treaty), as an ambitious forum to carry out dispute ...

, but when hostilities started he insisted that the war should be prosecuted vigorously. By the secession of the Southern senators, the Republicans acquired control of the senate and placed Fessenden at the head of the finance committee. During the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

, he was the most conspicuous senator in sustaining the national credit. He opposed the Legal Tender Act

Legal tender is a form of money that courts of law are required to recognize as satisfactory payment for any monetary debt. Each jurisdiction determines what is legal tender, but essentially it is anything which when offered ("tendered") in pa ...

as unnecessary and unjust. As chairman of the finance committee, Fessenden prepared and carried through the senate all measures relating to revenue, taxation, and appropriations, and, as declared by Charles Sumner

Charles Sumner (January 6, 1811March 11, 1874) was an American statesman and United States Senator from Massachusetts. As an academic lawyer and a powerful orator, Sumner was the leader of the anti-slavery forces in the state and a leader of th ...

, was "in the financial field all that our best generals were in arms."

President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

appointed Fessenden United States Secretary of the Treasury

The United States secretary of the treasury is the head of the United States Department of the Treasury, and is the chief financial officer of the federal government of the United States. The secretary of the treasury serves as the principal a ...

upon Salmon P. Chase

Salmon Portland Chase (January 13, 1808May 7, 1873) was an American politician and jurist who served as the sixth chief justice of the United States. He also served as the 23rd governor of Ohio, represented Ohio in the United States Senate, a ...

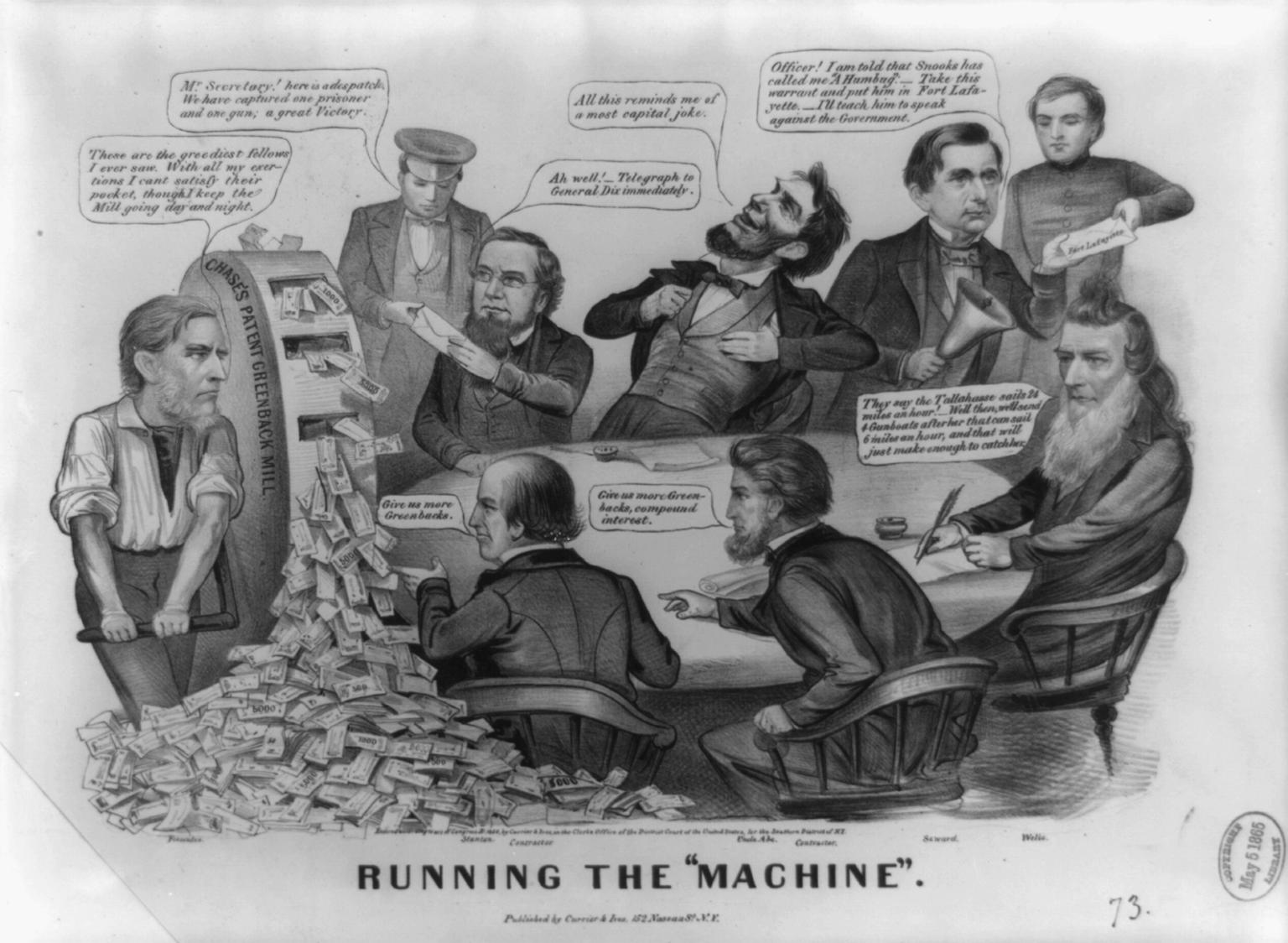

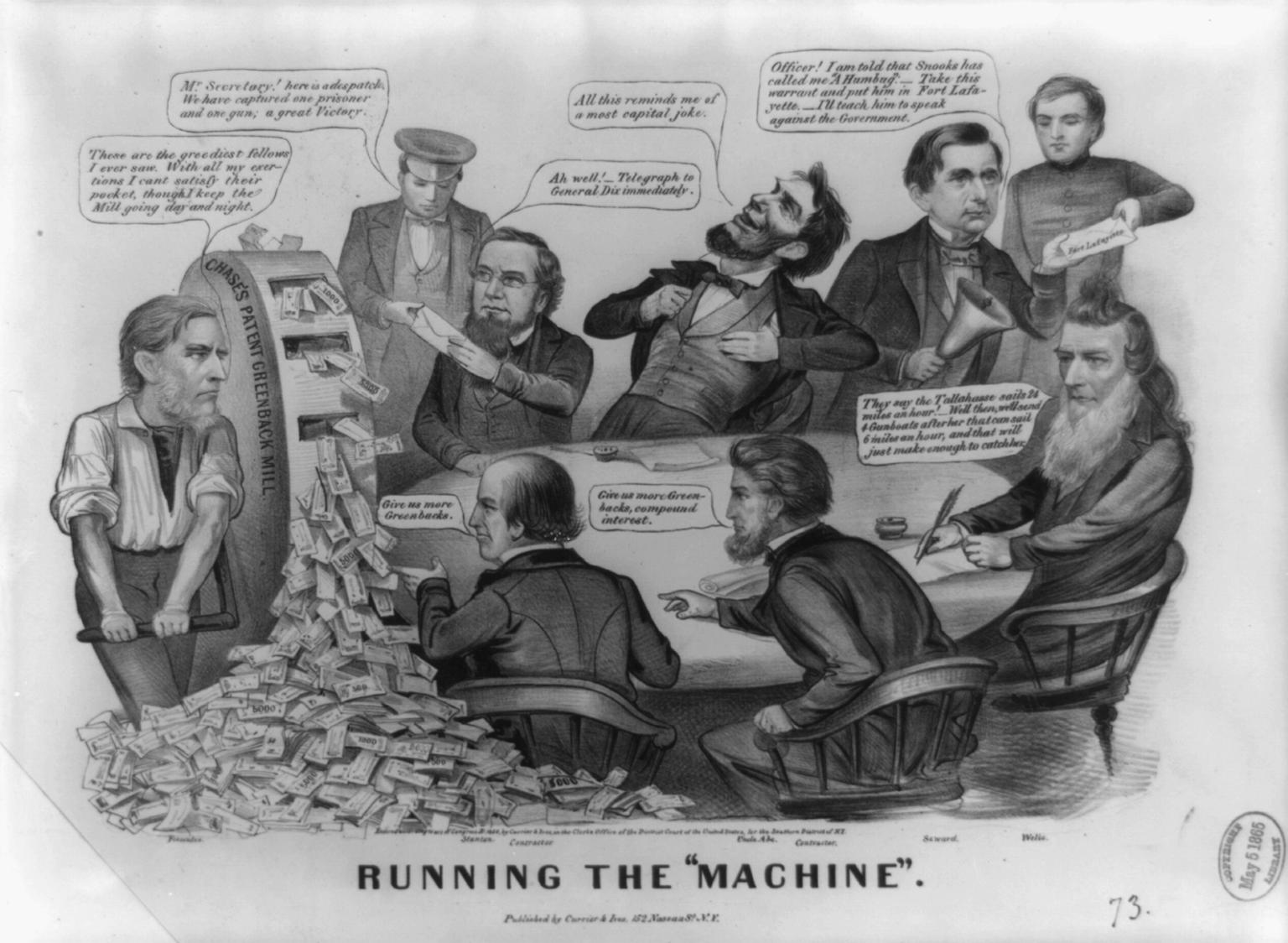

's resignation. It was described as the darkest hour of national finances in the United States. Chase had just withdrawn a loan from the market for want of acceptable bids, and the capacity of the country to lend seemed exhausted. The currency had been enormously inflated: the paper dollar was worth only 34 cents; gold was at $280/ounce. Fessenden at first refused the office, but at last, accepted in obedience to the universal public pressure. When his acceptance became known, gold fell to $225/ounce. He declared that no more currency should be issued, and, making an appeal to the people, he prepared and put upon the market the seven-thirty loan, which proved a triumphant success, and raised $400,000,000. This loan was in the form of bonds bearing interest at the rate of 7.30%, which were issued in denominations as low as $50 so that people of moderate means could take them. He also framed and recommended the measures, adopted by congress, which permitted the subsequent consolidation and funding of the government loans into the 4% and 4.5% bonds.

Fessenden began his service as Secretary of the Treasury on July 5, 1864. The financial situation becoming favorable on the raising of another large loan, in accordance with his expressed intention, he resigned the secretaryship, leaving on March 3, 1865, to return to the Senate, to which he had now for the third time been elected, and where he would serve for the rest of his life.

From 1865 to 1867, he headed the Joint Committee on Reconstruction, which was responsible for overseeing the readmission of states from the former Confederacy into the Union. He wrote its report, which vindicated the power of Congress over the rebellious states, showed their relations to the government under the constitution and the law of nations, and recommended the constitutional safeguards made necessary by the rebellion. At this point, Fessenden was the acknowledged leader in the Senate among Republicans and was considered a moderate rather than Radical Republican. Radical leader

Fessenden began his service as Secretary of the Treasury on July 5, 1864. The financial situation becoming favorable on the raising of another large loan, in accordance with his expressed intention, he resigned the secretaryship, leaving on March 3, 1865, to return to the Senate, to which he had now for the third time been elected, and where he would serve for the rest of his life.

From 1865 to 1867, he headed the Joint Committee on Reconstruction, which was responsible for overseeing the readmission of states from the former Confederacy into the Union. He wrote its report, which vindicated the power of Congress over the rebellious states, showed their relations to the government under the constitution and the law of nations, and recommended the constitutional safeguards made necessary by the rebellion. At this point, Fessenden was the acknowledged leader in the Senate among Republicans and was considered a moderate rather than Radical Republican. Radical leader Charles Sumner

Charles Sumner (January 6, 1811March 11, 1874) was an American statesman and United States Senator from Massachusetts. As an academic lawyer and a powerful orator, Sumner was the leader of the anti-slavery forces in the state and a leader of th ...

, deemed "too ultra," was snubbed entirely from the committee.

During President Andrew Johnson's

During President Andrew Johnson's impeachment trial

An impeachment trial is a trial that functions as a component of an impeachment. Several governments utilize impeachment trials as a part of their processes for impeachment, but differ as to when in the impeachment process trials take place and how ...

in 1868, Fessenden broke party ranks, along with six other Republican senators, and voted for acquittal. These seven Republican senators were disturbed by how the proceedings had been manipulated in order to give a one-sided presentation of the evidence. He, Joseph S. Fowler, James W. Grimes, John B. Henderson

John Brooks Henderson (November 16, 1826April 12, 1913) was a United States senator from Missouri and a co-author of the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. For his role in the investigation of the Whiskey Ring, he was cons ...

, Lyman Trumbull

Lyman Trumbull (October 12, 1813 – June 25, 1896) was a lawyer, judge, and United States Senator from Illinois and the co-author of the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

Born in Colchester, Connecticut, Trumbull esta ...

, Peter G. Van Winkle, and Edmund G. Ross defied their party and public opinion and voted against conviction. They were joined by three other Republican senators ( James Dixon, James Rood Doolittle

James Rood Doolittle (January 3, 1815July 27, 1897) was an American politician who served as a U.S. Senator from Wisconsin from March 4, 1857, to March 4, 1869. He was a strong supporter of President Abraham Lincoln's administration during the ...

, Daniel Sheldon Norton

Daniel Sheldon Norton (April 12, 1829July 13, 1870) was an American lawyer and politician who served in the Minnesota State Senate and as a U.S. Senator from Minnesota.

Life and career

Norton was born in Mount Vernon, Ohio to Daniel Sheldon and ...

) and all nine Democrats in voting against conviction. As a result, a 35–19 vote in favor of removing the President from office failed by a single vote of reaching a 2/3 majority. After the trial, Congressman Benjamin Butler

Benjamin Franklin Butler (November 5, 1818 – January 11, 1893) was an American major general of the Union Army, politician, lawyer, and businessman from Massachusetts. Born in New Hampshire and raised in Lowell, Massachusetts, Butler is ...

of Massachusetts conducted hearings on the widespread reports that Republican senators had been bribed to vote for Johnson's acquittal. In Butler's hearings, and in subsequent inquiries, there was increasing evidence that some acquittal votes were acquired by promises of patronage jobs and cash cards. This included Kansas

Kansas () is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its capital is Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to th ...

senator Edmund G. Ross, who was actively embroiled in patronage corruption.

He served as chairman of the Finance Committee during the 37th through 39th Congress

The 39th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from March 4, 1865 ...

es (from 1861 to 1867), which led to his Cabinet appointment. He also served as a chairman of the Committee on Public Buildings and Grounds during the 40th Congress

The 40th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from March 4, 1867, ...

, the Appropriations Committee during the 41st Congress and the U.S. Senate Committee on the Library, also during the 41st Congress. In 1867, he was one of two senators (the other was Senator Justin S. Morrill of Vermont) who voted against the purchase of Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U.S. ...

from Russia. His last speech in the Senate was upon the bill to strengthen the public credit. He advocated the payment of the principal of the public debt in gold and opposed the notion that it might lawfully be paid in depreciated greenbacks.

In 1867, Radical Republican senator Charles Sumner introduced legislation that would expand Reconstruction efforts that included the provision of homesteads to freedmen. Fessenden lamented in opposition: "That is more than we do for white men," to which Sumner retorted: "''White men have never been in slavery.''"

During the 1868 United States presidential election, Fessenden joined the other six pro-Johnson Republican senators in campaigning for Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

, who the race against Democratic nominee Horatio Seymour

Horatio Seymour (May 31, 1810February 12, 1886) was an American politician. He served as Governor of New York from 1853 to 1854 and from 1863 to 1864. He was the Democratic Party nominee for president in the 1868 United States presidential elec ...

.

For several years, he was a regent of the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums and education and research centers, the largest such complex in the world, created by the U.S. government "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge". Founded ...

. He received the degree of LL.D.

Legum Doctor (Latin: “teacher of the laws”) (LL.D.) or, in English, Doctor of Laws, is a doctorate-level academic degree in law or an honorary degree, depending on the jurisdiction. The double “L” in the abbreviation refers to the early ...

from Bowdoin in 1858, and from Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of high ...

in 1864.

Fessenden died on September 8, 1869, while serving in the U.S. Senate. He was interred at the Evergreen Cemetery in Portland, Maine. On December 14, 1869, George Henry Williams

George Henry Williams (March 26, 1823April 4, 1910) was an American judge and politician. He served as chief justice of the Oregon Supreme Court, was the 32nd Attorney General of the United States, and was elected Oregon's U.S. senator, and serv ...

addressed the U.S. Senate to deliver a tribute to his friend and fellow Senator.Williams, George H. (1895). Occasional Addresses. Portland, Oregon: F.W. Baltes and Company. pp. 21–28.

Personal life

Two of his brothers, Samuel Clement Fessenden andThomas Amory Deblois Fessenden

Thomas Amory Deblois Fessenden (January 23, 1826 – September 28, 1868) was an American politician. He was a U.S. Representative from Maine.

__NOTOC__

Biography

Born in Portland, Maine, he attended North Yarmouth Academy and Dartmouth College ...

, were also Congressmen.

Fessenden married Ellen M. Deering in 1832, and she died in 1857. They had three sons who served in the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

: Samuel Fessenden, who was killed at the Second Battle of Bull Run, the Brigadier-General James Deering Fessenden, and the Major-General Francis Fessenden

Francis Fessenden (March 18, 1839 – January 2, 1906) was an American lawyer, politician, and soldier from the state of Maine who served as a general in the Union Army during the American Civil War.Eicher, p. 234. He was a member of the powe ...

, the latter of whom wrote a two-volume biography of his father, ''The Life and Services of William Pitt Fessenden,'' which was published in 1907. A fourth son, William Howard Fessenden

William is a male given name of Germanic origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norman conquest of Eng ...

, stayed in Maine to take care of the law practice his father had established. Their fifth child was Mary Elizabeth Deering Fessenden who died in childhood.

Actress Beverly Garland

Beverly Lucy Garland (née Fessenden; October 17, 1926 – December 5, 2008) was an American actress. Her work in feature films primarily consisted of small parts in a few major productions or leads in low-budget action or science-fiction movie ...

is his great-great-granddaughter who dropped her real name Fessenden and went by her married name Garland.

In popular culture

*In the 2012 film ''Lincoln

Lincoln most commonly refers to:

* Abraham Lincoln (1809–1865), the sixteenth president of the United States

* Lincoln, England, cathedral city and county town of Lincolnshire, England

* Lincoln, Nebraska, the capital of Nebraska, U.S.

* Lincol ...

'', Fessenden is played by actor Walt Smith.

See also

*Economic history of the United States Civil War The economic history of the American Civil War concerns the financing of the Union (American Civil War), Union and Confederate States of America, Confederate war efforts from 1861 to 1865, and the economic impact of the war.

The Union economy grew ...

* List of United States Congress members who died in office (1790–1899)

* Liberal Republican Party

Notes

Further reading

* , the source for much of this article. * Bordewich, Fergus M. ''How Republican Reformers Fought the Civil War, Defied Lincoln, Ended Slavery, and Remade America'' (2020) * Cook, Robert J. "Stiffening Abe: William Pitt Fessenden and the Role of the Broker Politician in the Civil War Congress." ''American Nineteenth Century History'' 8.2 (2007): 145-167. * Cook, Robert J. "'The Grave of All My Comforts': William Pitt Fessenden as Secretary of the Treasury, 1864–65." ''Civil War History'' 41.3 (1995): 208–226. * Cook, Robert J.Civil War Senator: William Pitt Fessenden and the Fight to Save the American Republic

' (Louisiana State University Press; 2011) 344 pages; a standard scholarly biography * Fessenden, Francis. ''Life and Public Services of William Pitt Fessenden: United States Senator from Maine 1854-1864; Secretary of the Treasury 1864-1865; United States Senator from Maine 1865-1869'' (1907

online

* Jellison, Charles.

Fessenden of Maine, Civil War Senator

' (1962), a standard scholarly biography * Landis, Michael Todd. "'A Champion Had Come': William Pitt Fessenden and the Republican Party, 1854–60," ''American Nineteenth Century History,'' Sept 2008, Vol. 9 Issue 3, pp. 269–285 * Richardson, Heather Cox. ''The Greatest Nation of the Earth: Republican Economic Policies during the Civil War'' (1997)

External links

* *External links

IncludesGuide to Research Collections

' where his papers are located.

Biography at Lincoln's White House

, - , - , - , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Fessenden, William P. 1806 births 1869 deaths 19th-century American politicians 19th-century American Episcopalians Republican Party members of the Maine House of Representatives United States Secretaries of the Treasury People of Maine in the American Civil War Union (American Civil War) political leaders Bowdoin College alumni Fessenden family Politicians from Portland, Maine People from Boscawen, New Hampshire Maine Oppositionists Republican Party United States senators from Maine Lincoln administration cabinet members Whig Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Maine Radical Republicans Moderate Republicans (Reconstruction era)