William Clarke (priest) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

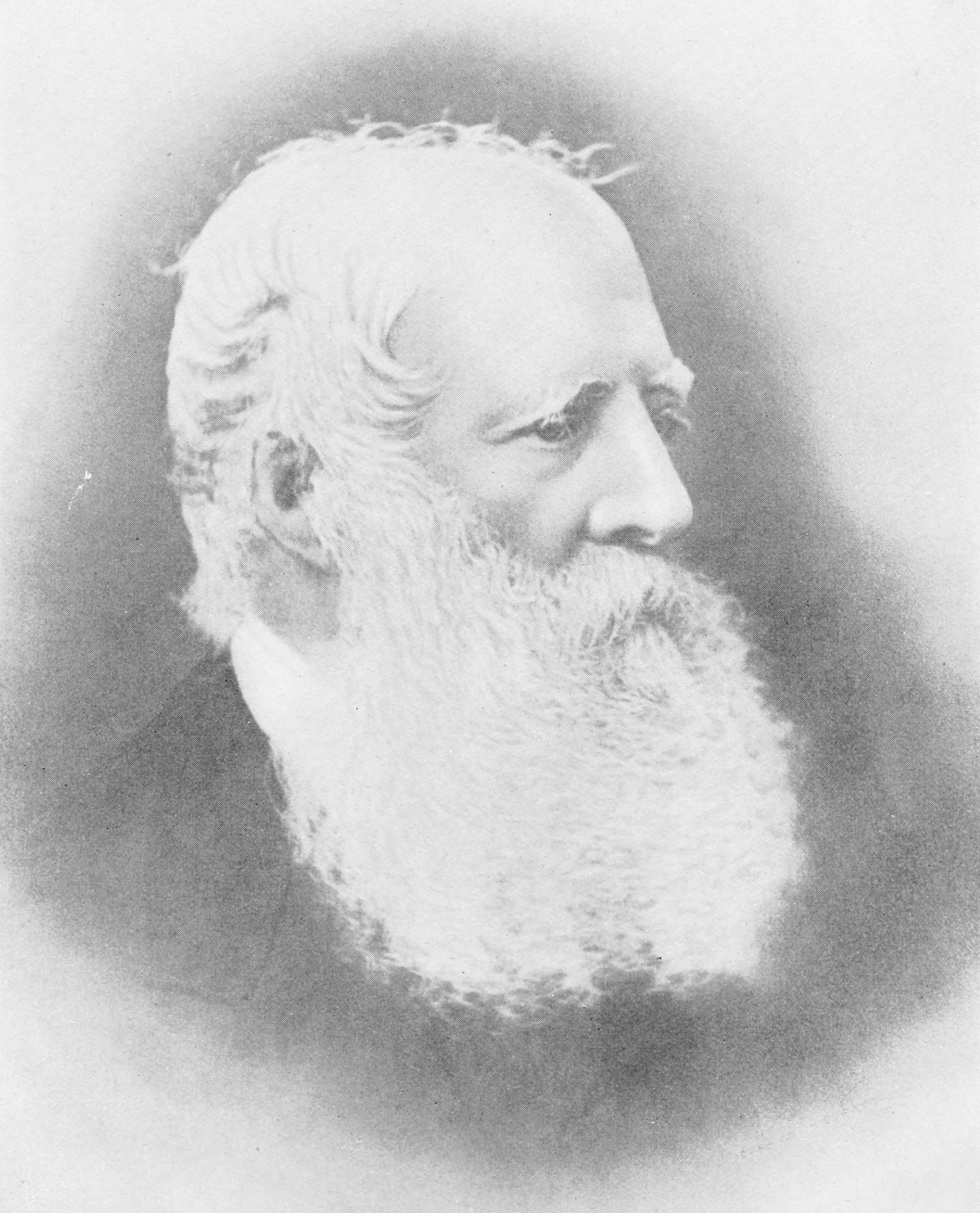

William Branwhite Clarke, FRS (2 June 179816 June 1878) was an English geologist and clergyman, active in Australia.

Clarke was a trustee of the

Clarke was a trustee of the

Clarke, William Branwhite (1798–1878)

, '' Australian Dictionary of Biography'', Volume 3, MUP, 1969, pp 420–422. *

Early life and England

Clarke was born atEast Bergholt

East Bergholt is a village in the Babergh District of Suffolk, England, just north of the Essex border.

The nearest town and railway station is Manningtree, Essex. East Bergholt is north of Colchester and south of Ipswich. Schools include Ea ...

, in Suffolk, the eldest child of William Clarke, schoolmaster, and his wife Sarah, ''née'' Branwhite. He was partly educated at his father's house, under the Rev. R. G. S. Brown, B.D., and partly at Dedham Grammar School. In October 1817 he went to Cambridge and entered into residence at Jesus College. In 1819 he entered a poem for the Chancellor's Gold Medal

The Chancellor's Gold Medal is a prestigious annual award at Cambridge University for poetry, paralleling Oxford University's Newdigate Prize. It was first presented by Prince William Frederick, Duke of Gloucester and Edinburgh during his time as ...

; this was awarded to Macaulay, but Clarke's poem ''Pompeii'', published in the same year, was judged second. He took his BA degree in 1821, and obtained his MA degree in 1824. In 1821 he was appointed curate of Ramsholt in Suffolk, and he acted in his clerical capacity in other places until 1839. He was also master of the Free School of East Bergholt for about 18 months in 1830–1. Having become interested in geology through the teachings of Adam Sedgwick, he used his opportunities and gathered many interesting facts on the geology of East Anglia which were embodied in a paper ''On the Geological Structure and Phenomena of Suffolk'' (Trans. Geol. Soc. 1837). He also communicated a series of papers on the geology of S.E. to the Magazine of Nat. Hist. (1837–1838).

Career in Australia

In 1839, after a severe illness, Clarke left England forNew South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

, mainly with the object of benefiting by the sea voyage. He had been commissioned by some of his English colleagues to ascertain the extent and character of the carboniferous formation in New South Wales (Clarke's letter to Sydney Morning Herald, 18 February 1852). He remained, however, in that country, and came to be regarded as the Father of Australian Geology.

Clarke was headmaster of The King's School, Parramatta

Parramatta () is a suburb and major Central business district, commercial centre in Greater Western Sydney, located in the state of New South Wales, Australia. It is located approximately west of the Sydney central business district on the ban ...

, in May 1839 until the end of 1840. Until 1870 he ministered to parishes from Parramatta to the Hawkesbury River

The Hawkesbury River, or Hawkesbury-Nepean River, is a river located northwest of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. The Hawkesbury River and its associated main tributary, the Nepean River, almost encircle the metropolitan region of Sydney.

...

, then of Campbelltown, and finally of Willoughby. He zealously devoted attention to the geology of the country, with results that have been of paramount importance. In 1841 he found specimens of gold, but he was not the first European who had obtained it in situ in the country. (This honour goes correctly to Government Surveyor James McBrien who found flakes at Locksley NSW in February 1823). Clarke described finding it both in the detrital deposits and in the quartz reefs west of the Blue Mountains, the same area where McBrien had found it, and he declared his belief in its abundance. Mr R Lowe, Lieutenant William Lawson, an unnamed convict (who was flogged for the discovery), Dr Johann Lhotsky, and "Count" Paul Strzelecki had also found gold in Australia before Clarke. It appears they mostly had found alluvial flakes, whereas Clarke had found it embedded in quartz rocks. Early in 1844 he showed the governor of New South Wales, Sir George Gipps

Sir George Gipps (23 December 1790 – 28 February 1847) was the Governor of the British colony of New South Wales for eight years, between 1838 and 1846. His governorship oversaw a tumultuous period where the rights to land were bitterly conte ...

, some specimens of gold he had found. Sir George asked him where he had got it, and when Clarke told him said "Put it away or we shall have our throats cut". Clarke, in his evidence before the select committee on his claims, which sat in 1861, stated that he knew of the existence of the gold in 1841. Clarke, however, agreed with Gipps that it may not be wise to announce the presence of gold in the colony. Clarke continued his clerical duties, but was occasionally lent to the government to carry out geological investigations. In 1849 he made the first discovery of tin

Tin is a chemical element with the symbol Sn (from la, stannum) and atomic number 50. Tin is a silvery-coloured metal.

Tin is soft enough to be cut with little force and a bar of tin can be bent by hand with little effort. When bent, t ...

in Australia and in 1859 he made known the occurrence of diamonds. He discovered secondary (Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 145 to 66 million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era, as well as the longest. At around 79 million years, it is the longest geological period of ...

) fossils in Queensland in 1860, he was also the first to indicate the presence of Silurian rocks, and to determine the age of the coal-bearing rocks in New South Wales. In 1869 he announced the discovery of remains of ''Dinornis

The giant moa (''Dinornis'') is an extinct genus of birds belonging to the moa family. As with other moa, it was a member of the order Dinornithiformes. It was endemic to New Zealand. Two species of ''Dinornis'' are considered valid, the North ...

'' in Queensland

)

, nickname = Sunshine State

, image_map = Queensland in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Queensland in Australia

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, establishe ...

. He finished the preparation of the fourth edition of his ''Remarks on the Sedimentary Formations of New South Wales'' on his eightieth birthday, and died a fortnight later on 16 June 1878. He was buried in the St Thomas cemetery, the graveyard of the North Shore church he was rector of for many years; and his widow and some descendants and relatives are close by.

Legacy

Clarke was a trustee of the

Clarke was a trustee of the Australian Museum

The Australian Museum is a heritage-listed museum at 1 William Street, Sydney central business district, New South Wales, Australia. It is the oldest museum in Australia,Design 5, 2016, p.1 and the fifth oldest natural history museum in the ...

at Sydney, and an active member of the Royal Society of New South Wales of which he was vice-president 1866–1878; the Clarke Medal

The Clarke Medal is awarded by the Royal Society of New South Wales, the oldest learned society in Australia and the Southern Hemisphere, for distinguished work in the Natural sciences.

The medal is named in honour of the Reverend William Branw ...

awarded by the Society is named in his honour. In 1860 he published ''Researches in the Southern Gold Fields of New South Wales''. He was elected Fellow of the Royal Society

Fellowship of the Royal Society (FRS, ForMemRS and HonFRS) is an award granted by the judges of the Royal Society of London to individuals who have made a "substantial contribution to the improvement of natural knowledge, including mathemat ...

in 1876, and in the following year was awarded the Murchison Medal

The Murchison Medal is an academic award established by Roderick Murchison, who died in 1871. First awarded in 1873, it is normally given to people who have made a significant contribution to geology by means of a substantial body of research and ...

by the Geological Society of London

The Geological Society of London, known commonly as the Geological Society, is a learned society based in the United Kingdom. It is the oldest national geological society in the world and the largest in Europe with more than 12,000 Fellows.

Fe ...

. His contributions to Australian scientific journals were numerous. He died near Sydney. His name is commemorated in the William Clarke College

William Clarke College is an independent, P-12, co-educational Anglican College located in Kellyville in Sydney's north west (Hills District), Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a sovereign country co ...

school at Kellyville, NSW and the WB Clarke Geoscience Centre at Londonderry, NSW operated by the Geological Survey of New South Wales.

His works in geology included the field of palaeontology and his collections and receipt of fossil material formed the foundation of research on Australia's extinct flora and fauna. Clarke did not describe the specimens he avidly collected throughout his life, these were instead forwarded to societies in England for their scientific examination. The results of his contemporaries studies and descriptions of Australian palaeontology and geology were incorporated into his own publications, and he remained current with advances in these fields despite his remote location.

See also

* Australian gold rushes *William Clarke College

William Clarke College is an independent, P-12, co-educational Anglican College located in Kellyville in Sydney's north west (Hills District), Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a sovereign country co ...

References

General references

* * *Ann Mozley,Clarke, William Branwhite (1798–1878)

, '' Australian Dictionary of Biography'', Volume 3, MUP, 1969, pp 420–422. *

External links

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Clarke, William Branwhite 1798 births 1878 deaths People from East Bergholt Alumni of Jesus College, Cambridge 19th-century English Anglican priests English geologists Australian Anglican priests Australian geologists Fellows of the Royal Society Australian people of English descent 19th-century Australian scientists