William B. Cushing on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

William Barker Cushing (4 November 184217 December 1874) was an officer in the

On the night of 27–28 October 1864, Cushing and his men began working their way upriver. A small cutter accompanied them, its crew having the task of preventing interference by the Confederate sentries stationed on a

On the night of 27–28 October 1864, Cushing and his men began working their way upriver. A small cutter accompanied them, its crew having the task of preventing interference by the Confederate sentries stationed on a  The explosion threw everyone aboard the steam launch into the water. Recovering quickly, Cushing stripped off his uniform and swam to shore, where he hid until daylight. That afternoon, having avoided detection by Confederate search parties, he stole a small skiff and quietly paddled down-river to rejoin the

The explosion threw everyone aboard the steam launch into the water. Recovering quickly, Cushing stripped off his uniform and swam to shore, where he hid until daylight. That afternoon, having avoided detection by Confederate search parties, he stole a small skiff and quietly paddled down-river to rejoin the

On 31 January 1872, he was promoted to the rank of commander, becoming the youngest up to that time to attain that rank in the Navy. Two weeks later he was detached to await orders. Weeks of waiting turned into months, but no word came. He had given up hope of another sea command, when early in June 1873, Cushing had an offer to take command of . He took command of his new ship on 11 July 1873.Schneller 2004, pp. 98–101.

He commanded ''Wyoming'' with his typical flair for being where the action was, performing daring and courageous acts. ''Wyoming''s boilers broke down twice, and in April she was ordered to Norfolk for extensive repairs. On 24 April, Cushing was detached and put on a waiting list for reassignment. He believed that he would be given ''Wyoming'' again when she was ready for duty, but in truth, his ill-health would not permit him to command another vessel.

Cushing returned to Fredonia to see his new daughter, Katherine Abell, who had been born on 11 October 1873. His wife was shocked to see the condition of her husband. His health was in apparent decline. Kate remarked to William's mother that he looked to be a man of sixty instead of his thirty-one years. Cushing had begun having severe attacks of pain in his hip as early as just after the sinking of the ''Albemarle.''

None of the doctors he saw were able to make a diagnosis. The term "

On 31 January 1872, he was promoted to the rank of commander, becoming the youngest up to that time to attain that rank in the Navy. Two weeks later he was detached to await orders. Weeks of waiting turned into months, but no word came. He had given up hope of another sea command, when early in June 1873, Cushing had an offer to take command of . He took command of his new ship on 11 July 1873.Schneller 2004, pp. 98–101.

He commanded ''Wyoming'' with his typical flair for being where the action was, performing daring and courageous acts. ''Wyoming''s boilers broke down twice, and in April she was ordered to Norfolk for extensive repairs. On 24 April, Cushing was detached and put on a waiting list for reassignment. He believed that he would be given ''Wyoming'' again when she was ready for duty, but in truth, his ill-health would not permit him to command another vessel.

Cushing returned to Fredonia to see his new daughter, Katherine Abell, who had been born on 11 October 1873. His wife was shocked to see the condition of her husband. His health was in apparent decline. Kate remarked to William's mother that he looked to be a man of sixty instead of his thirty-one years. Cushing had begun having severe attacks of pain in his hip as early as just after the sinking of the ''Albemarle.''

None of the doctors he saw were able to make a diagnosis. The term "

Cushing's grave is marked by a large, monumental casket made of marble, on which in relief, are Cushing's hat, sword, and coat. On one side of the stone the word "Albemarle" is cut and on the other side, "Fort Fisher".

Five ships in the U.S. Navy have been named after him. The most recent one, the , was decommissioned in September 2005.

Cushing has a portrait of him in full dress uniform hanging in Memorial Hall at the

Cushing's grave is marked by a large, monumental casket made of marble, on which in relief, are Cushing's hat, sword, and coat. On one side of the stone the word "Albemarle" is cut and on the other side, "Fort Fisher".

Five ships in the U.S. Navy have been named after him. The most recent one, the , was decommissioned in September 2005.

Cushing has a portrait of him in full dress uniform hanging in Memorial Hall at the

United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

, best known for sinking the during a daring nighttime raid on 27 October 1864, for which he received the Thanks of Congress The Thanks of Congress is a series of formal resolutions passed by the United States Congress originally to extend the government's formal thanks for significant victories or impressive actions by American military commanders and their troops. Altho ...

. Cushing was the younger brother of Medal of Honor

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is the United States Armed Forces' highest military decoration and is awarded to recognize American soldiers, sailors, marines, airmen, guardians and coast guardsmen who have distinguished themselves by acts of valor. ...

recipient Alonzo Cushing

Alonzo Hereford Cushing (January 19, 1841 – July 3, 1863) was an artillery officer in the Union Army during the American Civil War. He was killed in action during the Battle of Gettysburg while defending the Union position on Cemetery Ridge again ...

. As a result, the Cushing family is the only family in American history to have a member buried at more than one of the United States Service Academies

The United States service academies, also known as the United States military academies, are United States federal academies, federal academies for the undergraduate education and training of commissioned officers for the United States Armed Fo ...

.

Biography

Early life

Cushing was born inDelafield, Wisconsin

Delafield is a city in Waukesha County, Wisconsin, along the Bark River. The population was 7,085 at the 2010 census.

The city of Delafield is a separate municipality from the Town of Delafield, both of which are situated in township 7 North ...

, and was the youngest of four brothers and had two sisters. After the death of his father when he was still a young child, the family relocated to Fredonia, New York

Fredonia is a village in Chautauqua County, New York, United States. The population was 9,871 as of the 2020 census. Fredonia is in the town of Pomfret south of Lake Erie. The village is the home of the State University of New York at Fredonia ( ...

. He was expelled from the United States Naval Academy

The United States Naval Academy (US Naval Academy, USNA, or Navy) is a federal service academy in Annapolis, Maryland. It was established on 10 October 1845 during the tenure of George Bancroft as Secretary of the Navy. The Naval Academy ...

, just before graduation, for pranks and poor scholarship. At the outbreak of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, however, he pleaded his case to United States Secretary of the Navy

The secretary of the Navy (or SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the United States Department of the Navy, Department of the Navy, a military department (component organization) within the United States D ...

Gideon Welles

Gideon Welles (July 1, 1802 – February 11, 1878), nicknamed "Father Neptune", was the United States Secretary of the Navy from 1861 to 1869, a cabinet post he was awarded after supporting Abraham Lincoln in the 1860 election. Although opposed ...

himself, was reinstated and went on to acquire a distinguished record, frequently volunteering for the most hazardous missions. "His heroism, good luck and coolness under fire were legendary."

Civil War

Cushing saw action during theBattle of Hampton Roads

The Battle of Hampton Roads, also referred to as the Battle of the ''Monitor'' and ''Virginia'' (rebuilt and renamed from the USS ''Merrimack'') or the Battle of Ironclads, was a naval battle during the American Civil War.

It was fought over t ...

and at Fort Fisher

Fort Fisher was a Confederate fort during the American Civil War. It protected the vital trading routes of the port at Wilmington, North Carolina, from 1861 until its capture by the Union in 1865. The fort was located on one of Cape Fear River' ...

, among many others. He was promoted to lieutenant in 1862, and to commander in 1872. Two of his brothers died in uniform, Alonzo H. Cushing in the Battle of Gettysburg

The Battle of Gettysburg () was fought July 1–3, 1863, in and around the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, by Union and Confederate forces during the American Civil War. In the battle, Union Major General George Meade's Army of the Po ...

, for which he was awarded the Medal of Honor, and Howard B. Cushing

Howard Bass Cushing (August 22, 1838–May 5, 1871) was an American soldier during the American Civil War and the Indian Wars, who was killed by the Apache during a campaign in Arizona Territory.(Kenneth A. Randall, Only the Echoes - The Life ...

, while fighting the Chiricahua Apache

Chiricahua ( ) is a band of Apache Native Americans.

Based in the Southern Plains and Southwestern United States, the Chiricahua (Tsokanende ) are related to other Apache groups: Ndendahe (Mogollon, Carrizaleño), Tchihende (Mimbreño), Sehende ...

s in 1871. His eldest brother, Milton, served in the Navy as a paymaster

A paymaster is someone appointed by a group of buyers, sellers, investors or lenders to receive, hold, and dispense funds, commissions, fees, salaries (remuneration) or other trade, loan, or sales proceeds within the private sector or public secto ...

.

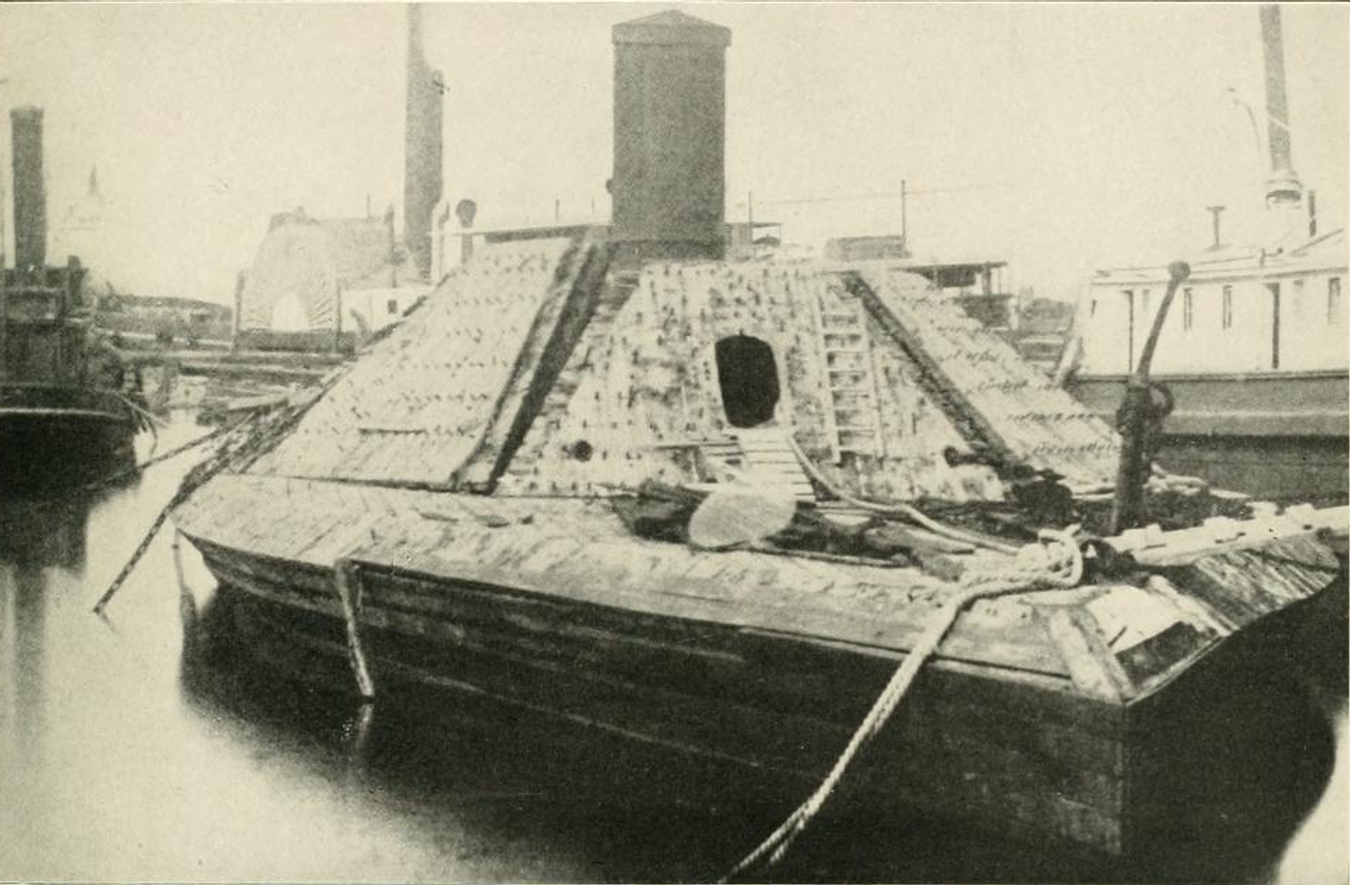

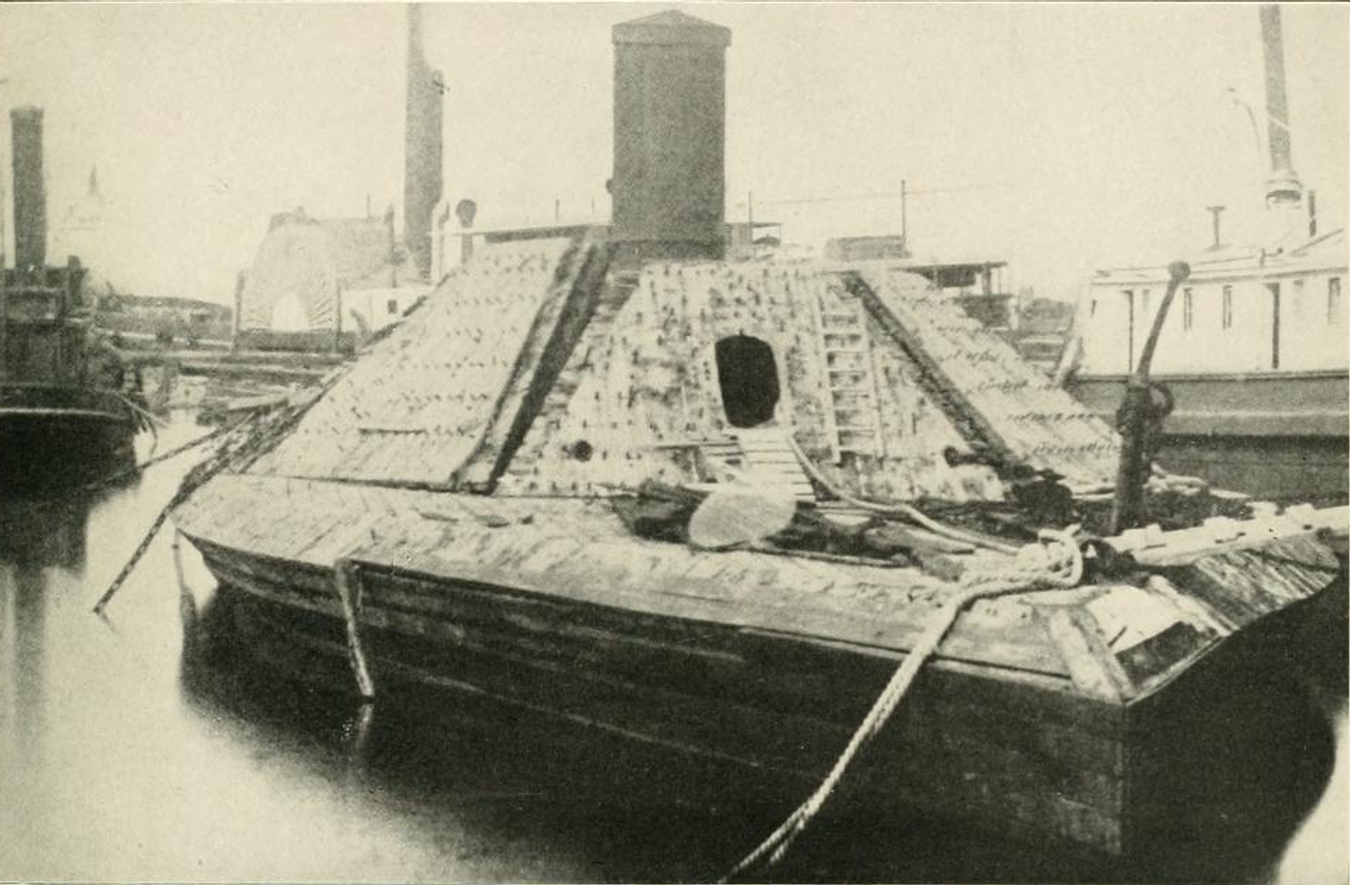

It was Cushing's daring plan and its successful execution against the Confederacy's ironclad ram that defined his military career. The powerful ironclad dominated the Roanoke River

The Roanoke River ( ) runs long through southern Virginia and northeastern North Carolina in the United States. A major river of the southeastern United States, it drains a largely rural area of the coastal plain from the eastern edge of the App ...

and the approaches to Plymouth

Plymouth () is a port city and unitary authority in South West England. It is located on the south coast of Devon, approximately south-west of Exeter and south-west of London. It is bordered by Cornwall to the west and south-west.

Plymouth ...

through the summer of 1864. By autumn, the U.S. government decided that the situation should be studied to determine if something could be done. The U.S. Navy considered various ways to destroy ''Albemarle'', including two daring plans submitted by Lieutenant Cushing. They finally approved one of his plans and authorized him to locate two small steam launches that might be fitted with spar torpedo

A spar torpedo is a weapon consisting of a bomb placed at the end of a long pole, or spar, and attached to a boat. The weapon is used by running the end of the spar into the enemy ship. Spar torpedoes were often equipped with a barbed spear at ...

es.

Cushing discovered two picket boats under construction in New York and acquired them for his mission. On each he mounted a 12-pound Dahlgren howitzer and a spar projecting into the water from its bow. One of the boats was lost at sea during the voyage from New York to Norfolk, Virginia

Norfolk ( ) is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. Incorporated in 1705, it had a population of 238,005 at the 2020 census, making it the third-most populous city in Virginia after neighboring Virginia Be ...

, but the other arrived safely with its crew of seven officers and men at the mouth of the Roanoke. There, the steam launch's spar was fitted with a lanyard-detonated torpedo.

On the night of 27–28 October 1864, Cushing and his men began working their way upriver. A small cutter accompanied them, its crew having the task of preventing interference by the Confederate sentries stationed on a

On the night of 27–28 October 1864, Cushing and his men began working their way upriver. A small cutter accompanied them, its crew having the task of preventing interference by the Confederate sentries stationed on a schooner

A schooner () is a type of sailing vessel defined by its rig: fore-and-aft rigged on all of two or more masts and, in the case of a two-masted schooner, the foremast generally being shorter than the mainmast. A common variant, the topsail schoon ...

anchored to the wreck of . When both boats, under the cover of darkness, slipped past the schooner undetected, Cushing decided to use all 22 of his men and the element of surprise to capture ''Albemarle''.

As they approached the Confederate

Confederacy or confederate may refer to:

States or communities

* Confederate state or confederation, a union of sovereign groups or communities

* Confederate States of America, a confederation of secessionist American states that existed between 1 ...

docks, their luck turned and even though under the cover of darkness they were spotted by a guard dog. They came under heavy sentry fire from both the shore and aboard ''Albemarle''. As they closed with ''Albemarle'', they quickly discovered she was defended against approach by floating log booms. The logs, however, had been in the water for many months and were covered with heavy slime. The steam launch rode up and then over them without difficulty. When her spar was fully against the ironclad's hull, Cushing stood up in the bow and detonated the torpedo's explosive charge.Stempel 2011, p. 204.

The explosion threw everyone aboard the steam launch into the water. Recovering quickly, Cushing stripped off his uniform and swam to shore, where he hid until daylight. That afternoon, having avoided detection by Confederate search parties, he stole a small skiff and quietly paddled down-river to rejoin the

The explosion threw everyone aboard the steam launch into the water. Recovering quickly, Cushing stripped off his uniform and swam to shore, where he hid until daylight. That afternoon, having avoided detection by Confederate search parties, he stole a small skiff and quietly paddled down-river to rejoin the Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

forces at the river's mouth. Of the other men in Cushing's boat, William Houghtman escaped, John Woodman and Richard Higgins were drowned, and 11 were captured.

Cushing's daring commando raid blew a hole in ''Albemarle''s hull at the waterline "big enough to drive a wagon in." She sank immediately in the six feet of water below her keel, settling into the heavy bottom mud, leaving the upper armored casemate mostly dry and the ironclad's large Stainless Banner battle ensign flying from its flag staff, where it was eventually captured as a Union prize.

Postbellum

After the Civil War, Cushing served in both thePacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

and Asiatic Squadron

The Asiatic Squadron was a squadron of United States Navy warships stationed in East Asia during the latter half of the 19th century. It was created in 1868 when the East India Squadron was disbanded. Vessels of the squadron were primarily invo ...

s; he was the executive officer of the and commanded the . He also served as ordnance officer in the Boston Navy Yard

The Boston Navy Yard, originally called the Charlestown Navy Yard and later Boston Naval Shipyard, was one of the oldest shipbuilding facilities in the United States Navy. It was established in 1801 as part of the recent establishment of t ...

.

Before taking command of USS ''Maumee,'' while he was on leave at home in Fredonia, Cushing met his sister's friend, Katherine Louise Forbes. 'Kate', as she was known, would sit and listen for hours to William's stories of adventure. Cushing asked her to marry him on 1 July 1867. Unfortunately, he received orders and was gone before a ceremony could take place. On 22 February 1870, Cushing and Forbes married. Their first daughter, Marie Louise, was born on 1 December 1871.

On 31 January 1872, he was promoted to the rank of commander, becoming the youngest up to that time to attain that rank in the Navy. Two weeks later he was detached to await orders. Weeks of waiting turned into months, but no word came. He had given up hope of another sea command, when early in June 1873, Cushing had an offer to take command of . He took command of his new ship on 11 July 1873.Schneller 2004, pp. 98–101.

He commanded ''Wyoming'' with his typical flair for being where the action was, performing daring and courageous acts. ''Wyoming''s boilers broke down twice, and in April she was ordered to Norfolk for extensive repairs. On 24 April, Cushing was detached and put on a waiting list for reassignment. He believed that he would be given ''Wyoming'' again when she was ready for duty, but in truth, his ill-health would not permit him to command another vessel.

Cushing returned to Fredonia to see his new daughter, Katherine Abell, who had been born on 11 October 1873. His wife was shocked to see the condition of her husband. His health was in apparent decline. Kate remarked to William's mother that he looked to be a man of sixty instead of his thirty-one years. Cushing had begun having severe attacks of pain in his hip as early as just after the sinking of the ''Albemarle.''

None of the doctors he saw were able to make a diagnosis. The term "

On 31 January 1872, he was promoted to the rank of commander, becoming the youngest up to that time to attain that rank in the Navy. Two weeks later he was detached to await orders. Weeks of waiting turned into months, but no word came. He had given up hope of another sea command, when early in June 1873, Cushing had an offer to take command of . He took command of his new ship on 11 July 1873.Schneller 2004, pp. 98–101.

He commanded ''Wyoming'' with his typical flair for being where the action was, performing daring and courageous acts. ''Wyoming''s boilers broke down twice, and in April she was ordered to Norfolk for extensive repairs. On 24 April, Cushing was detached and put on a waiting list for reassignment. He believed that he would be given ''Wyoming'' again when she was ready for duty, but in truth, his ill-health would not permit him to command another vessel.

Cushing returned to Fredonia to see his new daughter, Katherine Abell, who had been born on 11 October 1873. His wife was shocked to see the condition of her husband. His health was in apparent decline. Kate remarked to William's mother that he looked to be a man of sixty instead of his thirty-one years. Cushing had begun having severe attacks of pain in his hip as early as just after the sinking of the ''Albemarle.''

None of the doctors he saw were able to make a diagnosis. The term "sciatica

Sciatica is pain going down the leg from the lower back. This pain may go down the back, outside, or front of the leg. Onset is often sudden following activities like heavy lifting, though gradual onset may also occur. The pain is often described ...

" was used in those days without regard to cause for any inflammation of the sciatic nerve, or any pain in the region of the hip. Cushing may have had a ruptured intervertebral disc

An intervertebral disc (or intervertebral fibrocartilage) lies between adjacent vertebrae in the vertebral column. Each disc forms a fibrocartilaginous joint (a symphysis), to allow slight movement of the vertebrae, to act as a ligament to hold t ...

. He had suffered enough shocks to dislocate half a dozen vertebrae, and with the passage of time they came to bear more and more heavily upon the nerve. On the other hand, he may have been suffering from tuberculosis of the hip bone, or cancer of the prostate gland. There was nothing to be done and Cushing continued to suffer.

He was given the post of executive officer of the Washington Navy Yard

The Washington Navy Yard (WNY) is the former shipyard and ordnance plant of the United States Navy in Southeast Washington, D.C. It is the oldest shore establishment of the U.S. Navy.

The Yard currently serves as a ceremonial and administrativ ...

. He spent the summer of 1874 pretending to be happy with his inactive role. He played with his children and enjoyed their company. On 25 August, he was made senior aide at the yard; in the fall he amused himself by taking an active interest in the upcoming congressional elections.

On Thanksgiving

Thanksgiving is a national holiday celebrated on various dates in the United States, Canada, Grenada, Saint Lucia, Liberia, and unofficially in countries like Brazil and Philippines. It is also observed in the Netherlander town of Leiden and ...

Day, William, Kate and his mother went to church in the morning. That night, the pain in Cushing's back was worse than it had ever been and he could not sleep. The following Monday he dragged himself to the Navy Yard. Kate sent Lieutenant Hutchins, once of the ''Wyoming'' crew and now Cushing's aide, to bring his superior home. She feared that he wouldn't last the day. True to his nature, Cushing stayed at the yard until after nightfall, and went right to bed when he got home. He would not rise again. The pain was constant and terrible. He was given injections of morphine

Morphine is a strong opiate that is found naturally in opium, a dark brown resin in poppies (''Papaver somniferum''). It is mainly used as a analgesic, pain medication, and is also commonly used recreational drug, recreationally, or to make ...

, but that only dulled the pain a little.

On 8 December, it became impossible to care for Cushing at home, and he was removed to St. Elizabeths Hospital. His family visited him often, but he seldom recognized them. Cushing died on 17 December 1874, in the presence of his wife and mother. He was buried on 8 January 1875, at Bluff Point, at the United States Naval Academy Cemetery

The United States Naval Academy Cemetery and Columbarium is a cemetery at the United States Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland.

History

In 1868 the Naval Academy purchased a 67-acre piece of land called Strawberry Hill as part of their effort ...

in Annapolis

Annapolis ( ) is the capital city of the U.S. state of Maryland and the county seat of, and only incorporated city in, Anne Arundel County. Situated on the Chesapeake Bay at the mouth of the Severn River, south of Baltimore and about east o ...

.

Legacy

Cushing's grave is marked by a large, monumental casket made of marble, on which in relief, are Cushing's hat, sword, and coat. On one side of the stone the word "Albemarle" is cut and on the other side, "Fort Fisher".

Five ships in the U.S. Navy have been named after him. The most recent one, the , was decommissioned in September 2005.

Cushing has a portrait of him in full dress uniform hanging in Memorial Hall at the

Cushing's grave is marked by a large, monumental casket made of marble, on which in relief, are Cushing's hat, sword, and coat. On one side of the stone the word "Albemarle" is cut and on the other side, "Fort Fisher".

Five ships in the U.S. Navy have been named after him. The most recent one, the , was decommissioned in September 2005.

Cushing has a portrait of him in full dress uniform hanging in Memorial Hall at the United States Naval Academy

The United States Naval Academy (US Naval Academy, USNA, or Navy) is a federal service academy in Annapolis, Maryland. It was established on 10 October 1845 during the tenure of George Bancroft as Secretary of the Navy. The Naval Academy ...

at Annapolis. Nearly all of the other portraits in the hall are of admirals. A monument that honors Alonzo, William, and Howard Cushing is located at Cushing Memorial Park in Delafield, Wisconsin

Delafield is a city in Waukesha County, Wisconsin, along the Bark River. The population was 7,085 at the 2010 census.

The city of Delafield is a separate municipality from the Town of Delafield, both of which are situated in township 7 North ...

.

See also

*Notes

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * *External links

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Cushing, William B. 1842 births 1874 deaths People from Fredonia, New York People from Delafield, Wisconsin United States Naval Academy alumni Union Navy officers United States Navy officers People of New York (state) in the American Civil War People of Wisconsin in the American Civil War Burials at the United States Naval Academy Cemetery Military personnel from Wisconsin