Wiley Rutledge on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Wiley Blount Rutledge Jr. (July 20, 1894 – September 10, 1949) was an American jurist who served as an

Rutledge had no desire to be nominated to the Supreme Court, but his friends nonetheless wrote to Roosevelt and Biddle on his behalf. He wrote to Biddle disclaiming all interest in the position, and he admonished his friends with the words: "For God's sake, don't do anything about stirring up the matter! I am uncomfortable enough as it is." Still, Rutledge's supporters, most notably the well-regarded journalist

Rutledge had no desire to be nominated to the Supreme Court, but his friends nonetheless wrote to Roosevelt and Biddle on his behalf. He wrote to Biddle disclaiming all interest in the position, and he admonished his friends with the words: "For God's sake, don't do anything about stirring up the matter! I am uncomfortable enough as it is." Still, Rutledge's supporters, most notably the well-regarded journalist

Rutledge served as an

Rutledge served as an

In 80 percent of the criminal cases heard by the Supreme Court during his tenure, Rutledge voted in favor of the defendant—substantially more often than the Court as a whole, which did so in only 52 percent of criminal cases. He supported an expansive definition of due process and construed ambiguous statutes in favor of defendants, particularly in cases involving

In 80 percent of the criminal cases heard by the Supreme Court during his tenure, Rutledge voted in favor of the defendant—substantially more often than the Court as a whole, which did so in only 52 percent of criminal cases. He supported an expansive definition of due process and construed ambiguous statutes in favor of defendants, particularly in cases involving

In an act characterized by Urofsky as "the worst violation of civil liberties in American history", the Roosevelt administration ordered in 1942 that approximately 110,000 men, women, and children of Japanese ancestry—including about 70,000 native-born American citizens—be detained on the basis that they posed a threat to the war effort. The Supreme Court, with the agreement of Rutledge, conferred its imprimatur on this decision in the cases of ''

In an act characterized by Urofsky as "the worst violation of civil liberties in American history", the Roosevelt administration ordered in 1942 that approximately 110,000 men, women, and children of Japanese ancestry—including about 70,000 native-born American citizens—be detained on the basis that they posed a threat to the war effort. The Supreme Court, with the agreement of Rutledge, conferred its imprimatur on this decision in the cases of ''

Rutledge and his wife Annabel had three children: a son, Neal, and two daughters, Mary Lou and Jean Ann. Raised a Southern Baptist, Rutledge later became a

Rutledge and his wife Annabel had three children: a son, Neal, and two daughters, Mary Lou and Jean Ann. Raised a Southern Baptist, Rutledge later became a

associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States

An associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States is any member of the Supreme Court of the United States other than the chief justice of the United States. The number of associate justices is eight, as set by the Judiciary Act of 18 ...

from 1943 to 1949. The ninth and final justice appointed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

, he is known for his impassioned defenses of civil liberties

Civil liberties are guarantees and freedoms that governments commit not to abridge, either by constitution, legislation, or judicial interpretation, without due process. Though the scope of the term differs between countries, civil liberties may ...

. Rutledge favored broad interpretations of the First Amendment

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and rec ...

, the Due Process Clause

In United States constitutional law, a Due Process Clause is found in both the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution, which prohibits arbitrary deprivation of "life, liberty, or property" by the government except as ...

, and the Equal Protection Clause

The Equal Protection Clause is part of the first section of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. The clause, which took effect in 1868, provides "''nor shall any State ... deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal ...

, and he argued that the Bill of Rights applied in its totality to the states. He participated in several noteworthy cases involving the intersection of individual freedoms and the government's wartime powers. Rutledge served on the Court until his death at the age of fifty-five. Legal scholars have generally thought highly of the justice, although the brevity of his tenure has minimized his impact on history.

Born in Cloverport, Kentucky

Cloverport is a home rule-class city in Breckinridge County, Kentucky, United States, on the banks of the Ohio River. The population was 1,152 at the 2010 census.

History

The town was once known as Joesville after its founder, Joe Huston. Est ...

, Rutledge attended several colleges and universities, graduating with a Bachelor of Laws

Bachelor of Laws ( la, Legum Baccalaureus; LL.B.) is an undergraduate law degree in the United Kingdom and most common law jurisdictions. Bachelor of Laws is also the name of the law degree awarded by universities in the People's Republic of Chi ...

degree in 1922. He briefly practiced law in Boulder

In geology, a boulder (or rarely bowlder) is a rock fragment with size greater than in diameter. Smaller pieces are called cobbles and pebbles. While a boulder may be small enough to move or roll manually, others are extremely massive.

In c ...

, Colorado, before accepting a position on the faculty of the University of Colorado Law School

The University of Colorado Law School is one of the professional graduate schools within the University of Colorado System. It is a public law school, with more than 500 students attending and working toward a Juris Doctor or Master of Studies in ...

. Rutledge also taught law at the Washington University School of Law

Washington University in St. Louis School of Law (WashULaw) is the law school of Washington University in St. Louis, a private university in St. Louis, Missouri. WashULaw has consistently ranked among the top law schools in the country; it is ...

in St. Louis

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, which e ...

, Missouri, of which he became the dean

Dean may refer to:

People

* Dean (given name)

* Dean (surname), a surname of Anglo-Saxon English origin

* Dean (South Korean singer), a stage name for singer Kwon Hyuk

* Dean Delannoit, a Belgian singer most known by the mononym Dean

Titles

* ...

; he later served as dean of the University of Iowa College of Law

The University of Iowa College of Law is the law school of the University of Iowa, located in Iowa City, Iowa. It was founded in 1865. Iowa is ranked the 28th-best law school in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or U ...

. As an academic, he vocally opposed Supreme Court decisions striking down parts of the New Deal

The New Deal was a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1939. Major federal programs agencies included the Civilian Cons ...

and argued in favor of President Roosevelt's unsuccessful attempt to expand the Court. Rutledge's support of Roosevelt's policies brought him to the President's attention: he was considered as a potential Supreme Court nominee and was appointed to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia

The United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit (in case citations, D.C. Cir.) is one of the thirteen United States Courts of Appeals. It has the smallest geographical jurisdiction of any of the U.S. federal appellate cou ...

, where he developed a record as a supporter of individual liberties and the New Deal. When Justice James F. Byrnes

James Francis Byrnes ( ; May 2, 1882 – April 9, 1972) was an American judge and politician from South Carolina. A member of the Democratic Party, he served in U.S. Congress and on the U.S. Supreme Court, as well as in the executive branch, mos ...

resigned from the Supreme Court, Roosevelt nominated Rutledge to take his place. The Senate overwhelmingly confirmed Rutledge by voice vote

In parliamentary procedure, a voice vote (from the Latin ''viva voce'', meaning "live voice") or acclamation is a voting method in deliberative assemblies (such as legislatures) in which a group vote is taken on a topic or motion by responding vo ...

, and he took the oath of office on February 15, 1943.

Rutledge's jurisprudence placed a strong emphasis on the protection of civil liberties. In ''Everson v. Board of Education

''Everson v. Board of Education'', 330 U.S. 1 (1947), was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court that applied the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment to state law. Prior to this decision, the clause, which states, "Congress ...

'' (1947), he authored an influential dissent in support of the separation of church and state

The separation of church and state is a philosophical and jurisprudential concept for defining political distance in the relationship between religious organizations and the state. Conceptually, the term refers to the creation of a secular sta ...

. He sided with Jehovah's Witnesses

Jehovah's Witnesses is a millenarian restorationist Christian denomination with nontrinitarian beliefs distinct from mainstream Christianity. The group reports a worldwide membership of approximately 8.7 million adherents involved in ...

seeking to invoke the First Amendment in cases such as ''West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette

''West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette'', 319 U.S. 624 (1943), is a landmark decision by the United States Supreme Court holding that the Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment protects students from being forced to salute the Ame ...

'' (1943) and ''Murdock v. Pennsylvania

''Murdock v. Pennsylvania'', 319 U.S. 105 (1943), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that an ordinance requiring door-to-door salespersons ("solicitors") to purchase a license was an unconstitutional tax on religious e ...

'' (1943); his majority opinion in ''Thomas v. Collins

Thomas may refer to:

People

* List of people with given name Thomas

* Thomas (name)

* Thomas (surname)

* Saint Thomas (disambiguation)

* Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, and Doctor of the Church

* Thomas the Ap ...

'' (1945) endorsed a broad interpretation of the Free Speech Clause. In a famed dissent in the wartime case of '' In re Yamashita'' (1946), Rutledge voted to void the war crimes conviction of the Japanese general Tomoyuki Yamashita

was a Japanese officer and convicted war criminal, who was a general in the Imperial Japanese Army during World War II. Yamashita led Japanese forces during the invasion of Malaya and Battle of Singapore, with his accomplishment of conquering ...

, condemning in ringing terms a trial that, in his view, violated the basic principles of justice and fairness enshrined in the Constitution. By contrast, he joined the majority in two cases—''Hirabayashi v. United States

''Hirabayashi v. United States'', 320 U.S. 81 (1943), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States, United States Supreme Court held that the application of curfews against members of a minority group were constitutional when the nati ...

'' (1943) and ''Korematsu v. United States

''Korematsu v. United States'', 323 U.S. 214 (1944), was a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of the United States to uphold the exclusion of Japanese Americans from the West Coast Military Area during World War II. The decision has been wid ...

'' (1944)—that upheld the Roosevelt administration's decision to intern tens of thousands of Japanese Americans during World War II. In other cases, Rutledge fervently supported broad due process

Due process of law is application by state of all legal rules and principles pertaining to the case so all legal rights that are owed to the person are respected. Due process balances the power of law of the land and protects the individual pers ...

rights in criminal cases, and he opposed discrimination against women, racial minorities, and the poor.

Rutledge was among the most liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

justices ever to serve on the Supreme Court. He favored a flexible and pragmatic approach to the law that prioritized the rights of individuals. On the Court, his views aligned most often with those of Justice Frank Murphy

William Francis Murphy (April 13, 1890July 19, 1949) was an American politician, lawyer and jurist from Michigan. He was a Democrat who was named to the Supreme Court of the United States in 1940 after a political career that included serving ...

. Rutledge died in 1949, having suffered a massive stroke, after six years' service on the Supreme Court. President Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Franklin ...

appointed the considerably more conservative Sherman Minton

Sherman "Shay" Minton (October 20, 1890 – April 9, 1965) was an American politician and jurist who served as a U.S. senator from Indiana and later became an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States; he was a member of the ...

to replace him. Although Rutledge frequently found himself in dissent during his lifetime, many of his views received greater acceptance during the era of the Warren Court

The Warren Court was the period in the history of the Supreme Court of the United States during which Earl Warren served as Chief Justice. Warren replaced the deceased Fred M. Vinson as Chief Justice in 1953, and Warren remained in office until ...

.

Early life and education

Wiley Blount Rutledge Jr. was born just outside ofCloverport, Kentucky

Cloverport is a home rule-class city in Breckinridge County, Kentucky, United States, on the banks of the Ohio River. The population was 1,152 at the 2010 census.

History

The town was once known as Joesville after its founder, Joe Huston. Est ...

, on July 20, 1894, to Mary Lou ( Wigginton) and Wiley Blount Rutledge. Wiley Sr., a native of western Tennessee, was a fundamentalist

Fundamentalism is a tendency among certain groups and individuals that is characterized by the application of a strict literal interpretation to scriptures, dogmas, or ideologies, along with a strong belief in the importance of distinguishing ...

Baptist clergyman who believed firmly in the literal inerrancy of the Bible. He attended seminary in Louisville, Kentucky

Louisville ( , , ) is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky and the 28th most-populous city in the United States. Louisville is the historical seat and, since 2003, the nominal seat of Jefferson County, on the Indiana border ...

, and then moved with his wife to pastor a church in Cloverport. After Wiley Jr.'s birth, his mother contracted tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in ...

; the family left Kentucky in search of a healthier climate. They moved first to Texas and Louisiana and then to Asheville, North Carolina

Asheville ( ) is a city in, and the county seat of, Buncombe County, North Carolina. Located at the confluence of the French Broad and Swannanoa rivers, it is the largest city in Western North Carolina, and the state's 11th-most populous cit ...

, where the elder Rutledge took up a pastorate. After his wife's death in 1903, Wiley Sr. relocated his family throughout Tennessee and Kentucky, where he held temporary pastorates before eventually accepting a permanent post in Maryville, Tennessee

Maryville is a city in and the county seat of Blount County, Tennessee, and is a suburb of Knoxville. Its population was 31,907 at the 2020 census.

It is included in the Knoxville Metropolitan Area and a short distance from popular tourist desti ...

.

In 1910, the sixteen-year-old Wiley Jr. enrolled at Maryville College

Maryville College is a private liberal arts college in Maryville, Tennessee. It was founded in 1819 by Presbyterian minister Isaac L. Anderson for the purpose of furthering education and enlightenment into the West. The college is one of the ...

. He studied Latin and Greek, successfully maintaining high grades throughout. One of his Greek instructors was Annabel Person, whom he later married. At Maryville, Rutledge participated vigorously in debate; he argued in support of Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

and against the progressivism of Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

. He also played football

Football is a family of team sports that involve, to varying degrees, kicking a ball to score a goal. Unqualified, the word ''football'' normally means the form of football that is the most popular where the word is used. Sports commonly c ...

, developed a reputation as a practical jokester, and began a romantic relationship with Person, who was five years his senior. For reasons that are not altogether clear, Rutledge—who had planned to study law upon his graduation and whose lowest grades were in the sciences—left Maryville, enrolled at the University of Wisconsin–Madison

A university () is an educational institution, institution of higher education, higher (or Tertiary education, tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several Discipline (academia), academic disciplines. Universities ty ...

, and decided to study chemistry. Lonely and struggling in his classwork, Rutledge had a difficult time in Wisconsin, and he later characterized it as being one of the "hardest" and most "painful" periods of his life. He graduated in 1914 with an A. B. degree.

Realizing that his talents did not lie in chemistry, Rutledge resumed his original plan to study law. Since he was unable to afford the University of Wisconsin's law school, he moved to Bloomington, Indiana

Bloomington is a city in and the county seat of Monroe County, Indiana, Monroe County in the central region of the U.S. state of Indiana. It is the List of municipalities in Indiana, seventh-largest city in Indiana and the fourth-largest outside ...

, where he taught high school and enrolled part-time at the Indiana University Law School. The difficulty of simultaneously working and studying put a serious strain on his health, and by 1915 he had developed a life-threatening case of tuberculosis. The ailing Rutledge removed himself to a sanatorium

A sanatorium (from Latin '' sānāre'' 'to heal, make healthy'), also sanitarium or sanitorium, are antiquated names for specialised hospitals, for the treatment of specific diseases, related ailments and convalescence. Sanatoriums are often ...

and gradually began to recover from his disease; while there, he married Person. Upon recovering, he moved with his wife to Albuquerque, New Mexico

Albuquerque ( ; ), ; kee, Arawageeki; tow, Vakêêke; zun, Alo:ke:k'ya; apj, Gołgéeki'yé. abbreviated ABQ, is the most populous city in the U.S. state of New Mexico. Its nicknames, The Duke City and Burque, both reference its founding in ...

, where he took a position teaching high school business classes. In 1920, Rutledge enrolled at the University of Colorado Law School

The University of Colorado Law School is one of the professional graduate schools within the University of Colorado System. It is a public law school, with more than 500 students attending and working toward a Juris Doctor or Master of Studies in ...

in Boulder

In geology, a boulder (or rarely bowlder) is a rock fragment with size greater than in diameter. Smaller pieces are called cobbles and pebbles. While a boulder may be small enough to move or roll manually, others are extremely massive.

In c ...

; he continued teaching high school as he again pursued the study of law. One of his professors was Herbert S. Hadley

Herbert Spencer Hadley (February 20, 1872 – December 1, 1927) was an American lawyer and a Republican Party politician from St. Louis, Missouri. Born in Olathe, Kansas, he was Missouri Attorney General from 1905 to 1909 and in 1908 was elec ...

, the former governor of Missouri. Rutledge later stated that he "owe more professionally to Governor Hadley than to any other person"; Hadley's support for Roscoe Pound

Nathan Roscoe Pound (October 27, 1870 – June 30, 1964) was an American legal scholar and educator. He served as Dean of the University of Nebraska College of Law from 1903 to 1911 and Dean of Harvard Law School from 1916 to 1936. He was a membe ...

's progressive theory of sociological jurisprudence

The sociology of law (legal sociology, or law and society) is often described as a sub-discipline of sociology or an interdisciplinary approach within legal studies. Some see sociology of law as belonging "necessarily" to the field of sociology, ...

influenced Rutledge's view of the law. Rutledge graduated with a Bachelor of Laws

Bachelor of Laws ( la, Legum Baccalaureus; LL.B.) is an undergraduate law degree in the United Kingdom and most common law jurisdictions. Bachelor of Laws is also the name of the law degree awarded by universities in the People's Republic of Chi ...

degree in 1922.

Career

Rutledge passed thebar examination

A bar examination is an examination administered by the bar association of a jurisdiction that a lawyer must pass in order to be admitted to the bar of that jurisdiction.

Australia

Administering bar exams is the responsibility of the bar associa ...

in June 1922 and took a job with the law firm of Goss, Kimbrough, and Hutchison in Boulder. In 1924, he accepted the position of associate professor of law at his alma mater, the University of Colorado. He taught a wide variety of classes, and his colleagues commented that he was experiencing "very considerable success". In 1926, Hadley—who had recently become chancellor of Washington University in St. Louis

Washington University in St. Louis (WashU or WUSTL) is a private research university with its main campus in St. Louis County, and Clayton, Missouri. Founded in 1853, the university is named after George Washington. Washington University is r ...

—offered Rutledge a full professorship at his university's law school; Rutledge accepted the offer and moved to St. Louis

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, which e ...

with his family that year. He spent nine years there, continuing to teach classes pertaining to many aspects of the law. From 1930 to 1935, Rutledge served as dean

Dean may refer to:

People

* Dean (given name)

* Dean (surname), a surname of Anglo-Saxon English origin

* Dean (South Korean singer), a stage name for singer Kwon Hyuk

* Dean Delannoit, a Belgian singer most known by the mononym Dean

Titles

* ...

of the law school; he then spent four years as dean of the University of Iowa College of Law

The University of Iowa College of Law is the law school of the University of Iowa, located in Iowa City, Iowa. It was founded in 1865. Iowa is ranked the 28th-best law school in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or U ...

.

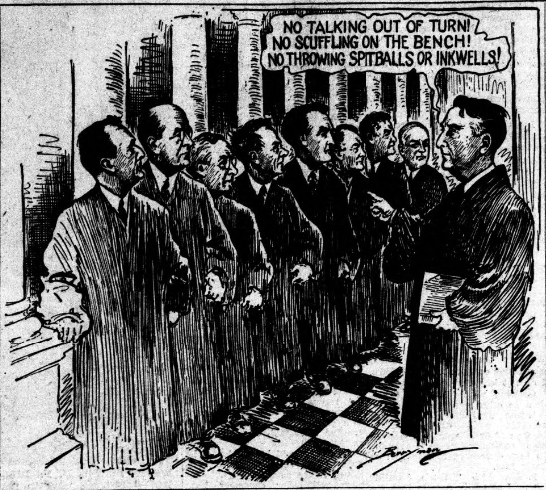

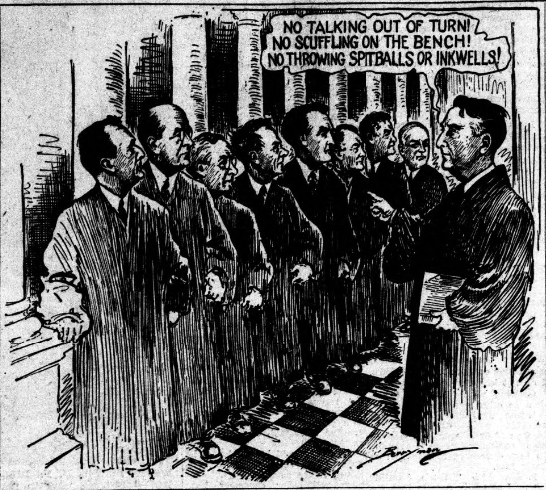

During his time in academia, Rutledge did not function primarily as a scholar: for instance, he only published two articles in law review

A law review or law journal is a scholarly journal or publication that focuses on legal issues. A law review is a type of legal periodical. Law reviews are a source of research, imbedded with analyzed and referenced legal topics; they also pro ...

s. Yet his students and colleagues thought highly of him as a teacher, and the legal scholar William Wiecek noted that he was recalled as "dedicated and demanding" by those whom he taught. Rutledge frequently weighed in on questions of public importance, supporting academic freedom and free speech at Washington University and opposing the Supreme Court's approach to child labor laws. His tenure as dean overlapped with the New Deal

The New Deal was a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1939. Major federal programs agencies included the Civilian Cons ...

-period clash between President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

and a Supreme Court whose decisions thwarted his agenda. Rutledge came down firmly on Roosevelt's side: he denounced the Court's rulings striking down portions of the New Deal and voiced support for the President's unsuccessful "court-packing plan", which attempted to make the Court more amenable to Roosevelt's agenda by increasing the number of justices. In Rutledge's view, the justices of his era had "imposed their own political philosophy" rather than the law in their decisions; as such, he felt that expanding the Court was a regrettable but necessary way for Congress to bring it back into line. Roosevelt's proposal was extremely unpopular in the Midwest, and Rutledge's support for it was loudly denounced: his position even led some members of the Iowa legislature

The Iowa General Assembly is the legislative branch of the state government of Iowa. Like the federal United States Congress, the General Assembly is a bicameral body, composed of the upper house Iowa Senate and the lower Iowa House of Repres ...

to threaten to freeze faculty salaries. Still, Roosevelt noticed Rutledge's outspoken support for him, and it garnered the dean prominence on the national stage. In the words of Rutledge himself, " e Court bill gave me my chance".

Court of Appeals (1939–1943)

Having attracted the attention of Roosevelt, Rutledge was seriously considered as a potential Supreme Court nominee when a vacancy arose in 1939. Although the President ultimately appointedFelix Frankfurter

Felix Frankfurter (November 15, 1882 – February 22, 1965) was an Austrian-American jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1939 until 1962, during which period he was a noted advocate of judicia ...

to that seat, he decided that it would be politically advantageous to appoint someone from west of the Mississippi—such as Rutledge—to fill the next opening. Roosevelt selected William O. Douglas

William Orville Douglas (October 16, 1898January 19, 1980) was an American jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, who was known for his strong progressive and civil libertarian views, and is often c ...

, who had lived in the states of Minnesota and Washington, instead of Rutledge when that vacancy arose, but he simultaneously offered Rutledge a seat on the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia

The United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit (in case citations, D.C. Cir.) is one of the thirteen United States Courts of Appeals. It has the smallest geographical jurisdiction of any of the U.S. federal appellate cou ...

—one of the nation's most influential appellate courts—which he accepted. Rutledge appeared before a Senate subcommittee; its members promptly endorsed the nomination. The full Senate speedily confirmed him by voice vote

In parliamentary procedure, a voice vote (from the Latin ''viva voce'', meaning "live voice") or acclamation is a voting method in deliberative assemblies (such as legislatures) in which a group vote is taken on a topic or motion by responding vo ...

on April 4, 1939, and he took the oath of office on May 2.

At the time, the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia heard a unique variety of matters: appeals from the federal district court in Washington, petitions to review the decisions of administrative agencies, and cases (similar to those decided by state supreme courts) arising from the District's local court system. As a judge of that court, therefore, Rutledge had the opportunity to write opinions on a wide variety of topics. In Wiecek's words, his 118 opinions "reflected his sympathetic views toward organized labor, the New Deal, and noneconomic individual rights". In ''Busey v. District of Columbia'', for instance, he dissented when the majority upheld several Jehovah's Witnesses

Jehovah's Witnesses is a millenarian restorationist Christian denomination with nontrinitarian beliefs distinct from mainstream Christianity. The group reports a worldwide membership of approximately 8.7 million adherents involved in ...

' convictions for distributing religious literature without securing a license and paying a tax. Writing that " xed speech is not free speech", Rutledge argued that the government could not charge those who wished to communicate on the streets. His opinion for the court in ''Wood v. United States'' reversed a conviction for robbery that had been secured after the defendant pleaded guilty at a preliminary hearing without having been informed of his right against self-incrimination

The right to silence is a legal principle which guarantees any individual the right to refuse to answer questions from law enforcement officers or court officials. It is a legal right recognized, explicitly or by convention, in many of the worl ...

. Rutledge wrote that the preliminary hearing was not supposed to be "a trap for luring the unwary into confession or admission which is fatal or prejudicial"; he held that a plea was not voluntary

Voluntary may refer to:

* Voluntary (music)

* Voluntary or volunteer, person participating via volunteering/volunteerism

* Voluntary muscle contraction

See also

* Voluntary action

* Voluntariness, in law and philosophy

* Voluntaryism

Volunt ...

if the defendant was not aware of his constitutional rights. Rutledge's jurisprudence emphasized the spirit of the law over the letter of the law; he rejected the use of technicalities to penalize individuals or to circumvent a law's underlying purpose. During his time on the Court of Appeals, he never rendered a single decision adverse to organized labor, and his rulings tended to be favorable toward administrative agencies and the New Deal more generally.

Supreme Court nomination

In October 1942, JusticeJames F. Byrnes

James Francis Byrnes ( ; May 2, 1882 – April 9, 1972) was an American judge and politician from South Carolina. A member of the Democratic Party, he served in U.S. Congress and on the U.S. Supreme Court, as well as in the executive branch, mos ...

resigned from the Supreme Court, creating the ninth and final vacancy of Roosevelt's presidency. As a result of Roosevelt's many previous appointments to the Court, there was "no obvious successor, no obvious political debt to be paid", according to the scholar Henry J. Abraham

Henry Julian Abraham (August 25, 1921 – February 26, 2020) was a German-born American scholar on the judiciary and constitutional law. He was James Hart Professor of Government Emeritus at the University of Virginia. He was the author of 13 ...

. Some prominent figures, including Justices Felix Frankfurter and Harlan F. Stone

Harlan Fiske Stone (October 11, 1872 – April 22, 1946) was an American attorney and jurist who served as an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1925 to 1941 and then as the 12th chief justice of the United States from 1941 un ...

, encouraged Roosevelt to appoint the distinguished jurist Learned Hand

Billings Learned Hand ( ; January 27, 1872 – August 18, 1961) was an American jurist, lawyer, and judicial philosopher. He served as a federal trial judge on the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York from 1909 to 1924 a ...

. However, the President was uncomfortable appointing the seventy-one-year-old Hand due to his age, as Roosevelt feared the appearance of hypocrisy due to the fact that he had cited the advanced age of Supreme Court justices to justify his plan to expand the Court Francis Biddle

Francis Beverley Biddle (May 9, 1886 – October 4, 1968) was an American lawyer and judge who was the United States Attorney General during World War II. He also served as the primary American judge during the postwar Nuremberg Trials as well a ...

, the attorney general, who disclaimed any interest in serving on the court himself, was asked by Roosevelt to search for a suitable nominee. A number of candidates were considered, including federal judge John J. Parker

John Johnston Parker (November 20, 1885 – March 17, 1958) was an American politician and United States circuit judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit. He was an unsuccessful nominee for associate justice of the Unite ...

, Solicitor General Charles Fahy

Charles Fahy (August 27, 1892 – September 17, 1979) was an American lawyer and judge who served as the 26th Solicitor General of the United States and later served as a United States circuit judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Di ...

, U.S. Senator Alben W. Barkley

Alben William Barkley (; November 24, 1877 – April 30, 1956) was an American lawyer and politician from Kentucky who served in both houses of Congress and as the 35th vice president of the United States from 1949 to 1953 under Presiden ...

, and Dean Acheson

Dean Gooderham Acheson (pronounced ; April 11, 1893October 12, 1971) was an American statesman and lawyer. As the 51st U.S. Secretary of State, he set the foreign policy of the Harry S. Truman administration from 1949 to 1953. He was also Truman ...

. But the journalist Drew Pearson soon named another possibility, whom he identified as "the candidate of Chief Justice Stone" in his columns and radio broadcasts: Wiley Rutledge.

Rutledge had no desire to be nominated to the Supreme Court, but his friends nonetheless wrote to Roosevelt and Biddle on his behalf. He wrote to Biddle disclaiming all interest in the position, and he admonished his friends with the words: "For God's sake, don't do anything about stirring up the matter! I am uncomfortable enough as it is." Still, Rutledge's supporters, most notably the well-regarded journalist

Rutledge had no desire to be nominated to the Supreme Court, but his friends nonetheless wrote to Roosevelt and Biddle on his behalf. He wrote to Biddle disclaiming all interest in the position, and he admonished his friends with the words: "For God's sake, don't do anything about stirring up the matter! I am uncomfortable enough as it is." Still, Rutledge's supporters, most notably the well-regarded journalist Irving Brant

Irving Newton Brant (January 17, 1885 September 18, 1976) was an American biographer, journalist, and historian. Early life

Brant was born on January 17, 1885, in Walker, Iowa, the son of David Brant, the editor of the local newspaper, and Ruth ...

, continued to lobby the White House to nominate him, and he stated in private that he would not decline the nomination if Roosevelt offered it to him. Biddle directed his assistant Herbert Wechsler

Herbert Wechsler (December 4, 1913 – April 26, 2004) was an American legal scholar and former director of the American Law Institute (ALI). He is most widely known for his constitutional law scholarship and for the creation of the Model Penal ...

to review Rutledge's record; Wechsler's report convinced Biddle that Rutledge's judicial opinions were "a bit pedestrian" but nonetheless "sound". Biddle, joined by Roosevelt loyalists such as Douglas, Senator George W. Norris

George William Norris (July 11, 1861September 2, 1944) was an American politician from the state of Nebraska in the Midwestern United States. He served five terms in the United States House of Representatives as a Republican, from 1903 until 1913 ...

, and Justice Frank Murphy

William Francis Murphy (April 13, 1890July 19, 1949) was an American politician, lawyer and jurist from Michigan. He was a Democrat who was named to the Supreme Court of the United States in 1940 after a political career that included serving ...

, thus recommended to the President that Rutledge be appointed. After meeting with Rutledge at the White House and being convinced by Biddle that the judge's judicial philosophy was fully aligned with his own, Roosevelt agreed. According to the scholar Fred L. Israel, Roosevelt found Rutledge to be "a liberal New Dealer who combined the President's respect for the academic community with four years of service on a leading federal appellate court". Additionally, the fact that Rutledge was a Westerner weighed in his favor. The President told his nominee: "Wiley, we had a number of candidates for the Court who were highly qualified, but they didn't have geography—you have that".

Roosevelt formally nominated Rutledge, who was then forty-eight years old, to the Supreme Court on January 11, 1943. The Senate Judiciary Committee

The United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary, informally the Senate Judiciary Committee, is a standing committee of 22 U.S. senators whose role is to oversee the Department of Justice (DOJ), consider executive and judicial nominations, a ...

voted on February 1 to approve Rutledge's nomination; the vote was 11–0, with four abstentions. Those four senators—North Dakota's William Langer

William "Wild Bill" Langer (September 30, 1886November 8, 1959) was a prominent American lawyer and politician from North Dakota, where he was an infamous character, bouncing back from a scandal that forced him out of the governor's office and ...

, West Virginia's Chapman Revercomb

William Chapman Revercomb (July 20, 1895 – October 6, 1979) was an American politician and lawyer. A Republican, he served two separate terms in the United States Senate representing the state of West Virginia.

Life and career

Revercomb was ...

, Montana's Burton K. Wheeler

Burton Kendall Wheeler (February 27, 1882January 6, 1975) was an attorney and an American politician of the Democratic Party in Montana, which he represented as a United States senator from 1923 until 1947.

Born in Massachusetts, Wheeler began ...

, and Michigan's Homer S. Ferguson

Homer Samuel Ferguson (February 25, 1889December 17, 1982) was an American attorney, professor, judge, United States senator from Michigan, Ambassador to the Philippines, and later a judge on the United States Court of Military Appeals.

Educa ...

—abstained due to uneasiness about Rutledge's support for Roosevelt's court-expansion plan. Ferguson later spoke with Rutledge and indicated that his concerns had been resolved, but Wheeler, who had strongly opposed Roosevelt's efforts to enlarge the Court, said that he would vote against the nomination when it came before the full Senate. The only senator to speak on the Senate floor in opposition to Rutledge was Langer, who characterized Rutledge as "a man who, so far as I can ascertain, never practiced law inside a courtroom or, so far as I know, seldom even visited one until he came to take a seat on the United States Circuit Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia" and commented that " e Court is not without a professor or two already." The Senate overwhelmingly confirmed Rutledge by a voice vote on February 8, and he took the oath of office on February 15.

Supreme Court (1943–1949)

Rutledge served as an

Rutledge served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court

An associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States is any member of the Supreme Court of the United States other than the chief justice of the United States. The number of associate justices is eight, as set by the Judiciary Act of ...

from 1943 until his death in 1949. He penned a total of sixty-five majority opinion

In law, a majority opinion is a judicial opinion agreed to by more than half of the members of a court. A majority opinion sets forth the decision of the court and an explanation of the rationale behind the court's decision.

Not all cases have ...

s, forty-five concurrences, and sixty-one dissents. The deeply fractured Court to which he was appointed consisted of a conservative bloc, consisting of Justices Frankfurter, Robert H. Jackson

Robert Houghwout Jackson (February 13, 1892 – October 9, 1954) was an American lawyer, jurist, and politician who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the Unit ...

, Stanley Forman Reed

Stanley Forman Reed (December 31, 1884 – April 2, 1980) was an American lawyer and jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1938 to 1957. He also served as U.S. Solicitor General from 1935 to 1938.

Born in Mas ...

, and Owen Roberts

Owen Josephus Roberts (May 2, 1875 – May 17, 1955) was an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court from 1930 to 1945. He also led two Roberts Commissions, the first of which investigated the attack on Pearl Harbor, and the seco ...

, and a liberal bloc, consisting of Justices Hugo Black

Hugo Lafayette Black (February 27, 1886 – September 25, 1971) was an American lawyer, politician, and jurist who served as a U.S. Senator from Alabama from 1927 to 1937 and as an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1937 to 1971. A ...

, Murphy, Douglas, Rutledge, and sometimes Stone. On a Court plagued by internecine squabbles, Rutledge was, according to the legal historian Lucas A. Powe Jr., "the sole member both personally liked and intellectually respected by every other member". He found it challenging to write opinions, and his writing style has been criticized as unnecessarily prolix and difficult to read. Rutledge frequently and strenuously dissented: the scholar Alfred O. Canon wrote that he was "in many respects... the chief dissenter of the Roosevelt Court".

Rutledge was one of the most liberal justices in the history of the Court. His approach to the law strongly emphasized the preservation of civil liberties, motivated by a fervent belief that the freedoms of individuals should be protected. Rutledge voted more often than any of his colleagues in favor of individuals who brought suit against the government, and he forcefully advocated for equal protection, access to the courts, due process, and the rights protected by the First Amendment.According to the legal scholar Lester E. Mosher, Rutledge "may be classed as a 'natural law realist' who combined the humanitarianism of Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

with the pragmatism of John Dewey

John Dewey (; October 20, 1859 – June 1, 1952) was an American philosopher, psychologist, and educational reformer whose ideas have been influential in education and social reform. He was one of the most prominent American scholars in the f ...

—he employed the tenets of pragmatism as a juristic tool or technique in applying 'natural law

Natural law ( la, ius naturale, ''lex naturalis'') is a system of law based on a close observation of human nature, and based on values intrinsic to human nature that can be deduced and applied independently of positive law (the express enacte ...

' concepts". His views particularly overlapped with those of Murphy, with whom he agreed in nearly seventy-five percent of the Court's non-unanimous cases. The Supreme Court at large did not often embrace Rutledge's views during his lifetime, but during the era of the Warren Court

The Warren Court was the period in the history of the Supreme Court of the United States during which Earl Warren served as Chief Justice. Warren replaced the deceased Fred M. Vinson as Chief Justice in 1953, and Warren remained in office until ...

they gained considerable acceptance.

First Amendment

Rutledge's appointment had an immediate effect on a Court that was decidedly split on questions involving the freedoms protected by theFirst Amendment

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and rec ...

. For instance, in '' Jones v. City of Opelika'', a 1942 case decided before Rutledge's ascension to the Court, a 5–4 majority had upheld the convictions of Jehovah's Witnesses for selling religious literature without obtaining a license and paying a tax. Rutledge's arrival the subsequent year gave that case's erstwhile dissenters a majority; in ''Murdock v. Pennsylvania

''Murdock v. Pennsylvania'', 319 U.S. 105 (1943), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that an ordinance requiring door-to-door salespersons ("solicitors") to purchase a license was an unconstitutional tax on religious e ...

'', they overruled ''Jones'' and struck down the tax as unconstitutional. Rutledge also joined the majority in another precedent-altering case involving Jehovah's Witnesses and the First Amendment: ''West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette

''West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette'', 319 U.S. 624 (1943), is a landmark decision by the United States Supreme Court holding that the Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment protects students from being forced to salute the Ame ...

''. In that landmark decision, the Court reversed its previous holding in ''Minersville School District v. Gobitis

''Minersville School District v. Gobitis'', 310 U.S. 586 (1940), was a decision by the Supreme Court of the United States involving the religious rights of public school students under the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. The Cou ...

'', ruling instead that the First Amendment forbade public schools from requiring students to recite the Pledge of Allegiance

The Pledge of Allegiance of the United States is a patriotic recited verse that promises allegiance to the flag of the United States and the republic of the United States of America. The first version, with a text different from the one used ...

. Writing for a 6–3 majority that included Rutledge, Justice Jackson wrote that: " there is any fixed star in our constitutional constellation, it is that no official, high or petty, can prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion or force citizens to confess by word or act their faith therein". According to the jurist and scholar John M. Ferren

John Maxwell Ferren (born July 21, 1937) is a Senior Federal tribunals in the United States#Article I tribunals, associate judge of the District of Columbia Court of Appeals. He served as an associate judge on the court from 1977 to 1997, left to ...

, Rutledge, by his vote in ''Barnette'', "established himself early as a concerned protector of religious freedom".

Among Rutledge's most influential free-speech opinions was in the 1945 case of ''Thomas v. Collins

Thomas may refer to:

People

* List of people with given name Thomas

* Thomas (name)

* Thomas (surname)

* Saint Thomas (disambiguation)

* Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, and Doctor of the Church

* Thomas the Ap ...

''. Writing for a 5–4 majority, he ruled unconstitutional a Texas statute that required union organizer

A union organizer (or union organiser in Commonwealth spelling) is a specific type of trade union member (often elected) or an appointed union official. A majority of unions appoint rather than elect their organizers.

In some unions, the orga ...

s to register and obtain a license before they could solicit individuals to join labor unions. The case arose when R. J. Thomas

Roland Jay Thomas (June 9, 1900 – April 18, 1967), also known as R. J. Thomas, was a left-wing leader of the American automobile workers union in the 1930s and 1940s. He grew up in eastern Ohio and attended the College of Wooster for t ...

, an official of the Congress of Industrial Organizations

The Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) was a federation of unions that organized workers in industrial unions in the United States and Canada from 1935 to 1955. Originally created in 1935 as a committee within the American Federation of ...

, gave a pro-union address in Texas without having registered; he argued that the law was an unconstitutional prior restraint

Prior restraint (also referred to as prior censorship or pre-publication censorship) is censorship imposed, usually by a government or institution, on expression, that prohibits particular instances of expression. It is in contrast to censorship ...

on his First Amendment rights. Rutledge rejected Texas's arguments that the law was subject only to rational-basis review because labor organizing was akin to the sort of ordinary business activity that states could freely regulate. Writing that "the indispensable democratic freedoms secured by the First Amendment" had a "preferred place" that could be abridged only in light of a "clear and present danger", he held that the law imposed an unjustified burden on Thomas's constitutional rights. In dissent, Justice Roberts argued that it was not constitutionally problematic to impose a neutral licensing requirement on organizers of public meetings. According to Ferren, Rutledge's "celebrated and controversial" opinion in ''Thomas'' exemplifies both the Court's pervasive 5–4 division on First Amendment issues throughout the 1940s and Rutledge's "nearly absolutist" interpretation of the Free Speech Clause.

In the case of ''Everson v. Board of Education

''Everson v. Board of Education'', 330 U.S. 1 (1947), was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court that applied the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment to state law. Prior to this decision, the clause, which states, "Congress ...

'', Rutledge rendered a noteworthy dissent in defense of the separation of church and state

The separation of church and state is a philosophical and jurisprudential concept for defining political distance in the relationship between religious organizations and the state. Conceptually, the term refers to the creation of a secular sta ...

. ''Everson'' was among the first decisions to interpret the Establishment Clause

In United States law, the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment to the United States Constitution, together with that Amendment's Free Exercise Clause, form the constitutional right of freedom of religion. The relevant constitutional text ...

of the First Amendment, which forbids the enactment of laws "respecting an establishment of religion". Writing for the majority, Justice Black concluded that the Fourteenth Amendment incorporated the Establishment Clause, meaning that it applied to the states as well as to the federal government. Quoting Thomas Jefferson, he argued that "the clause against establishment of religion by law was intended to erect 'a wall of separation between Church and State. But despite what Wiecek called a "fusillade of sweeping dicta

In general usage, a dictum ( in Latin; plural dicta) is an authoritative or dogmatic statement. In some contexts, such as legal writing and church cantata librettos, ''dictum'' can have a specific meaning.

Legal writing

In United States legal term ...

", Black nonetheless held for a 5–4 majority that the specific law at issue—a New Jersey statute that permitted parents to be reimbursed for the costs of sending their children to private religious schools by bus—did not violate the Establishment Clause. In dissent, Rutledge favored an even stricter understanding of the Establishment Clause than Black, maintaining that its purpose "was to create a complete and permanent separation of the spheres of religious activity and civil authority by comprehensively forbidding every form of public aid or support for religion". On that basis, he argued that the New Jersey law was unconstitutional because it provided indirect financial support for religious education. Although Rutledge's position in ''Everson'' was not vindicated by the Court's later Establishment Clause jurisprudence, Ferren argued that his dissent "remains as powerful a statement as any Supreme Court justice has written" in support of church–state separation.

In other cases, Rutledge evinced a near-uniform tendency to embrace defenses rooted in the First Amendment: in ''Terminiello v. City of Chicago

''Terminiello v. City of Chicago'', 337 U.S. 1 (1949), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that a " breach of peace" ordinance of the City of Chicago that banned speech that "stirs the public to anger, invites disput ...

'', he sided with a priest whose rhetorical attacks on Jews and the Roosevelt administration had provoked a riot; in ''United Public Workers v. Mitchell

''United Public Workers v. Mitchell'', 330 U.S. 75 (1947), is a 4-to-3 ruling by the United States Supreme Court which held that the Hatch Act of 1939, as amended in 1940, does not violate the First, Fifth, Ninth, or Tenth amendments to U.S. Co ...

'' and ''Oklahoma v. United States Civil Service Commission

''Oklahoma v. United States Civil Service Commission'', 330 U.S. 127 (1947), is a 5-to-2 ruling by the United States Supreme Court which held that the Hatch Act of 1939 did not violate the Tenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

Backgro ...

'', he dissented when the Court upheld the Hatch Act

The Hatch Act of 1939, An Act to Prevent Pernicious Political Activities, is a United States federal law. Its main provision prohibits civil service employees in the executive branch of the federal government, except the president and vice pre ...

's restrictions on civil servants' political activity; in ''Marsh v. Alabama

''Marsh v. Alabama'', 326 U.S. 501 (1946), was a case decided by the US Supreme Court, which ruled that a state trespassing statute could not be used to prevent the distribution of religious materials on a town's sidewalk even though the sidewalk ...

'', he joined the majority in holding a company town

A company town is a place where practically all stores and housing are owned by the one company that is also the main employer. Company towns are often planned with a suite of amenities such as stores, houses of worship, schools, markets and re ...

's restrictions on the distribution of religious literature unconstitutional. In only a single case—''Prince v. Massachusetts

''Prince v. Massachusetts'', 321 U.S. 158 (1944), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that the government has broad authority to regulate the actions and treatment of children. Parental authority is not absolute and ca ...

''—did he vote to reject an attempt to invoke the First Amendment. ''Prince'' involved a Jehovah's Witness who had been convicted of violating a Massachusetts child labor law by bringing her nine-year-old niece to distribute religious literature with her. Writing for a 5–4 majority, Rutledge held that Massachusetts's interest in protecting children's welfare outweighed the child's First Amendment rights; he argued that "parents may be free to become martyrs themselves. But it does not follow hat

A hat is a head covering which is worn for various reasons, including protection against weather conditions, ceremonial reasons such as university graduation, religious reasons, safety, or as a fashion accessory. Hats which incorporate mecha ...

they are free... to make martyrs of their children." His usual ally Murphy disagreed, arguing in dissent that the state had not demonstrated "the existence of any grave or immediate danger to any interest which it may lawfully protect". Rutledge's decision to reject the First Amendment argument presented in ''Prince'' may have stemmed more from his longstanding opposition to child labor than from his views on religious freedom.

Criminal procedure

In 80 percent of the criminal cases heard by the Supreme Court during his tenure, Rutledge voted in favor of the defendant—substantially more often than the Court as a whole, which did so in only 52 percent of criminal cases. He supported an expansive definition of due process and construed ambiguous statutes in favor of defendants, particularly in cases involving

In 80 percent of the criminal cases heard by the Supreme Court during his tenure, Rutledge voted in favor of the defendant—substantially more often than the Court as a whole, which did so in only 52 percent of criminal cases. He supported an expansive definition of due process and construed ambiguous statutes in favor of defendants, particularly in cases involving capital punishment

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

. In ''Louisiana ex rel. Francis v. Resweber __NOTOC__

''Louisiana ex rel. Francis v. Resweber'', 329 U.S. 459 (1947), is a case in which the U.S. Supreme Court was asked whether imposing capital punishment (the electric chair) a second time, after it failed in an attempt to execute Willie ...

'', Rutledge dissented from the Court's 5–4 holding that Louisiana could again endeavor to execute a prisoner after the electric chair

An electric chair is a device used to execute an individual by electrocution. When used, the condemned person is strapped to a specially built wooden chair and electrocuted through electrodes fastened on the head and leg. This execution method, ...

malfunctioned during the previous attempt. He joined the opinion of Justice Harold H. Burton

Harold Hitz Burton (June 22, 1888 – October 28, 1964) was an American politician and lawyer. He served as the 45th mayor of Cleveland, Ohio, as a U.S. Senator from Ohio, and as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United Stat ...

, who maintained that "death by installments" was a form of cruel and unusual punishment that violated the Due Process Clause. In the case of ''In re Oliver

''In re Oliver'', 333 U.S. 257 (1948), was a decision by the United States Supreme Court involving the application of the right of due process in state court proceedings. The Sixth Amendment in the Bill of Rights states that criminal prosecuti ...

'', Rutledge agreed with the majority that a conviction for contempt of court

Contempt of court, often referred to simply as "contempt", is the crime of being disobedient to or disrespectful toward a court of law and its officers in the form of behavior that opposes or defies the authority, justice, and dignity of the cour ...

was unlawful because a single judge, sitting as a one-man grand jury, had held proceedings in secret and given the defendant no opportunity to defend himself. Concurring separately, he argued for a broader definition of due process, decrying the Court's willingness to permit "selective departure from the "scheme of ordered personal liberty established by the Bill of Rights" in other cases. Rutledge's dissent in '' Ahrens v. Clark'' demonstrated what Ferren characterized as his "continued impatience... with procedural rules barring access to the federal courts". The Court in ''Ahrens'' ruled 6–3 that German nationals seeking writs of habeas corpus

''Habeas corpus'' (; from Medieval Latin, ) is a recourse in law through which a person can report an unlawful detention or imprisonment to a court and request that the court order the custodian of the person, usually a prison official, t ...

to stop their deportations could not lawfully sue in federal court in the District of Columbia. Aided by his law clerk John Paul Stevens

John Paul Stevens (April 20, 1920 – July 16, 2019) was an American lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1975 to 2010. At the time of his retirement, he was the second-oldes ...

, Rutledge dissented, concluding that the court in the District of Columbia had jurisdiction

Jurisdiction (from Latin 'law' + 'declaration') is the legal term for the legal authority granted to a legal entity to enact justice. In federations like the United States, areas of jurisdiction apply to local, state, and federal levels.

Jur ...

because the person having custody over the prisoners—the Attorney General

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general or attorney-general (sometimes abbreviated AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. The plural is attorneys general.

In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have exec ...

—was located there. He argued against what he viewed as "a jurisdictional limitation so destructive of the writ's availability and adaptability to all the varying conditions and devices by which liberty may be unlawfully restrained". Stevens later served on the Supreme Court himself; in his majority opinion in ''Rasul v. Bush

''Rasul v. Bush'', 542 U.S. 466 (2004), was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court in which the Court held that foreign nationals held in the Guantanamo Bay detention camp could petition federal courts for writs of ''habeas corpus ...

'', he cited Rutledge's ''Ahrens'' dissent to conclude that federal courts had jurisdiction over suits brought by detainees at Guantanamo Bay.

Rutledge maintained that the provisions of the Bill of Rights protected all criminal defendants, regardless of whether they were being tried in state or federal court. He dissented in ''Adamson v. California

''Adamson v. California'', 332 U.S. 46 (1947), was a United States Supreme Court case regarding the incorporation of the Fifth Amendment of the Bill of Rights. Its decision is part of a long line of cases that eventually led to the Selective I ...

'', in which the Court, by a vote of 5–4, held that the Fifth Amendment's protection against forced self-incrimination

In criminal law, self-incrimination is the act of exposing oneself generally, by making a statement, "to an accusation or charge of crime; to involve oneself or another ersonin a criminal prosecution or the danger thereof". (Self-incrimination ...

did not apply to the states. Joining a dissent written by Murphy, he agreed with Justice Black's position that the Due Process Clause incorporated the entirety of the Bill of Rights, but he went further than Black to suggest that it also conferred additional due process protections not found elsewhere in the Constitution. In another incorporation dispute, ''Wolf v. Colorado

''Wolf v. Colorado'', 338 U.S. 25 (1949), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court held 6—3 that, while the Fourth Amendment was applicable to the states, the exclusionary rule was not a necessary ingredient of the Fourth Amend ...

'', Rutledge dissented when the Court ruled 6–3 that the exclusionary rule

In the United States, the exclusionary rule is a legal rule, based on constitutional law, that prevents evidence collected or analyzed in violation of the defendant's constitutional rights from being used in a court of law. This may be consider ...

—the prohibition against using illegally seized evidence in court—did not apply to the states. He joined a dissent by Murphy and penned a separate opinion of his own, in which he argued that, without the exclusionary rule, the Fourth Amendment prohibition of unlawful searches and seizures "was a dead letter". Rutledge's dissent was eventually vindicated: in its 1961 decision in ''Mapp v. Ohio

''Mapp v. Ohio'', 367 U.S. 643 (1961), was a landmark decision of the Supreme Court of the United States, U.S. Supreme Court in which the Court ruled that the exclusionary rule, which prevents prosecutors from using Evidence (law), evidence in co ...

'', the Court expressly overruled ''Wolf''.

Wartime cases

''In re Yamashita''

In the 1946 case of '' In re Yamashita'', Rutledge rendered an opinion that was later characterized by Ferren as "one of the Court's truly great, and influential, dissents". The case involved the Japanese generalTomoyuki Yamashita

was a Japanese officer and convicted war criminal, who was a general in the Imperial Japanese Army during World War II. Yamashita led Japanese forces during the invasion of Malaya and Battle of Singapore, with his accomplishment of conquering ...

, who commanded soldiers of the Imperial Japanese Army

The was the official ground-based armed force of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945. It was controlled by the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff Office and the Ministry of the Army, both of which were nominally subordinate to the Emperor o ...

in the Philippines during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. At the end of the war, troops under Yamashita's command killed tens of thousands of Filipinos, many of whom were civilians. On the basis that he was responsible for the actions of his troops, Yamashita was charged with war crimes and tried before a military commission. At trial, the prosecution could not demonstrate either that Yamashita was aware of the atrocities committed by his troops or that he had any control over their actions; witnesses testified that they were responsible for the killings and that Yamashita had no knowledge of them. The commission, which consisted of five American generals, nonetheless found him guilty and sentenced him to death by hanging. Yamashita petitioned the Supreme Court for a writ of habeas corpus, arguing that the conviction was unlawful due to a bevy of procedural irregularities, including the admission of hearsay

Hearsay evidence, in a legal forum, is testimony from an under-oath witness who is reciting an out-of-court statement, the content of which is being offered to prove the truth of the matter asserted. In most courts, hearsay evidence is inadmis ...

and fabricated evidence, restrictions on the defense's ability to cross-examine

In law, cross-examination is the interrogation of a witness called by one's opponent. It is preceded by direct examination (in Ireland, the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, South Africa, India and Pakistan known as examination-in-chief) and ...

witnesses, a lack of time for the defense to prepare its case, and a dearth of proof that Yamashita (as opposed to his troops) was guilty. Although the justices desired to stay out of questions of military justice, Rutledge and Murphy, who were gravely worried by what they viewed as serious procedural problems, convinced their colleagues to grant review and hear arguments in the case.

On February 4, 1946, the Court ruled by a 6–2 vote against Yamashita, upholding the result of the trial. Writing for the majority, Chief Justice Stone stated that the Court could consider only whether the military commission was validly formed, not whether Yamashita was innocent or guilty. Since the United States had not yet signed a peace treaty with Japan, he maintained that the Articles of War

The Articles of War are a set of regulations drawn up to govern the conduct of a country's military and naval forces. The first known usage of the phrase is in Robert Monro's 1637 work ''His expedition with the worthy Scot's regiment called Mac-k ...

permitted military trials to be conducted without complying with the Constitution's due process requirements. Arguing that military tribunals "are not courts whose rulings and judgments are made subject to review by this Court", he declined to address the other issues presented by the case. The two dissenters—Murphy and Rutledge—each filed separate opinions; according to Yamashita's lawyer, they read them "in tones so bitter and in language so sharp that it was readily apparent to all listeners that even more acrimonious expression must have marked the debate behind the scenes". In a dissent that scholars have characterized as "eloquent", "moving", and "magisterial", Rutledge decried the trial as an egregious violation of the ideals of justice and fairness protected by the Constitution. He denounced the majority opinion as an abdication of the Court's responsibility to apply the rule of law

The rule of law is the political philosophy that all citizens and institutions within a country, state, or community are accountable to the same laws, including lawmakers and leaders. The rule of law is defined in the ''Encyclopedia Britannica ...

to all, even to the military. Rutledge wrote:

Rutledge wrote privately that he felt the case would "outrank ''Dred Scott

Dred Scott (c. 1799 – September 17, 1858) was an Slavery in the United States, enslaved African Americans, African American man who, along with his wife, Harriet Robinson Scott, Harriet, unsuccessfully sued for freedom for themselves and thei ...

'' in the annals of the Court". In his dissent, he rejected the majority's holding that the Fifth Amendment was inapplicable, writing that: " t heretofore has it been held that any human being is beyond its universally protecting spread in the guaranty of a fair trial in the most fundamental sense. That door is dangerous to open. I will have no part in opening it. For once it is ajar, even for enemy belligerents, it can be pushed back wider for others, perhaps ultimately for all." Rebutting Stone's contentions point by point, Rutledge concluded that the charges against Yamashita were defective, that the evidence against him was inadequate and unlawfully admitted, and that the trial had violated the Articles of War, the 1929 Geneva Convention, and the Fifth Amendment's Due Process Clause. In closing, he quoted the words of Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine (born Thomas Pain; – In the contemporary record as noted by Conway, Paine's birth date is given as January 29, 1736–37. Common practice was to use a dash or a slash to separate the old-style year from the new-style year. In th ...

: "He that would make his own liberty secure must guard even his enemy from oppression; for if he violates this duty he establishes a precedent that will reach to himself." Although Rutledge's dissent did not prevent Yamashita from being hanged, the legal historian Melvin I. Urofsky

Melvin I. Urofsky is an American historian, and professor emeritus at Virginia Commonwealth University.

He received his B.A. from Columbia University in 1961 and doctorate in 1968. He also received his JD from the University of Virginia.

He teache ...

has written that its "influence, however, cannot be gainsaid ... The Court has not been involved with any war crimes trials in several decades, but aside from the jurisdictional issue it is clear that the ideas expressed by Wiley Rutledge—in terms of both due process and command accountability—have triumphed."

Japanese internment

In an act characterized by Urofsky as "the worst violation of civil liberties in American history", the Roosevelt administration ordered in 1942 that approximately 110,000 men, women, and children of Japanese ancestry—including about 70,000 native-born American citizens—be detained on the basis that they posed a threat to the war effort. The Supreme Court, with the agreement of Rutledge, conferred its imprimatur on this decision in the cases of ''

In an act characterized by Urofsky as "the worst violation of civil liberties in American history", the Roosevelt administration ordered in 1942 that approximately 110,000 men, women, and children of Japanese ancestry—including about 70,000 native-born American citizens—be detained on the basis that they posed a threat to the war effort. The Supreme Court, with the agreement of Rutledge, conferred its imprimatur on this decision in the cases of ''Hirabayashi v. United States

''Hirabayashi v. United States'', 320 U.S. 81 (1943), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States, United States Supreme Court held that the application of curfews against members of a minority group were constitutional when the nati ...

'' and ''Korematsu v. United States

''Korematsu v. United States'', 323 U.S. 214 (1944), was a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of the United States to uphold the exclusion of Japanese Americans from the West Coast Military Area during World War II. The decision has been wid ...

''. The first of these cases arose when Gordon Hirabayashi

was an American sociologist, best known for his principled resistance to the Japanese American internment during World War II, and the court case which bears his name, ''Hirabayashi v. United States''.

Early life

Hirabayashi was born in Seattl ...

, a college student born in the United States, was arrested, convicted, and jailed for refusing to comply with the order to report for relocation. Before the Supreme Court, he argued that the order unlawfully discriminated against Japanese Americans on the basis of race. The Court unanimously rejected his plea: in an opinion by Chief Justice Stone, it refused to question the military's assertion that the relocation program was critical to national security. Rutledge wrote privately that he had experienced "more anguish over this case" than almost any other, but he eventually voted to sustain Hirabayashi's conviction. In a brief concurrence, he disagreed with Stone's argument that courts had no authority whatsoever to review wartime actions of the military but joined the remainder of the majority opinion.

When the ''Korematsu'' case arrived at the Court the subsequent year, it had become clear to many that the internment program was unjustifiable: not a single Japanese American had been charged with treason or espionage, and the American military had largely neutralized the threat that Japan posed. Yet by a 6–3 vote, the Court rejected Fred Korematsu

was an American civil rights activist who resisted the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. Shortly after the Imperial Japanese Navy launched its attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Or ...

's challenge to the orders, again choosing to defer to the military and to Congress. Writing for the majority, Justice Black authored what Wiecek called "an almost schizophrenic opinion, unpersuasive in its arguments and ambiguous in its ultimate impact". Justices Roberts, Jackson, and Murphy dissented: Roberts decried the "clear violation of Constitutional rights" implicit in punishing an American citizen "for not submitting to imprisonment in a concentration camp, based on his ancestry, and solely because of his ancestry, without evidence or inquiry concerning his loyalty and good disposition toward the United States", while Murphy characterized the orders as a "fall ... into the ugly abyss of racism". Rutledge joined Black's opinion immediately and unreservedly, silently taking part in what Ferren called "one of the saddest episodes in the Court's history".

The legal scholar Lester E. Mosher wrote that Rutledge's vote in ''Korematsu'' "represents the only deviation in his record as a champion of civil rights". Addressing the question of why the justice chose to depart from his customary support for equality and civil liberties in ''Yamashita'', the law professor Craig Green observes that Rutledge had great faith in the Roosevelt administration and was hesitant to question its assertions that the internment orders were vital to national security. Green also argues that the modern condemnation of the Court's decision benefits substantially from hindsight: after the attack on Pearl Harbor