Western Ukraine on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

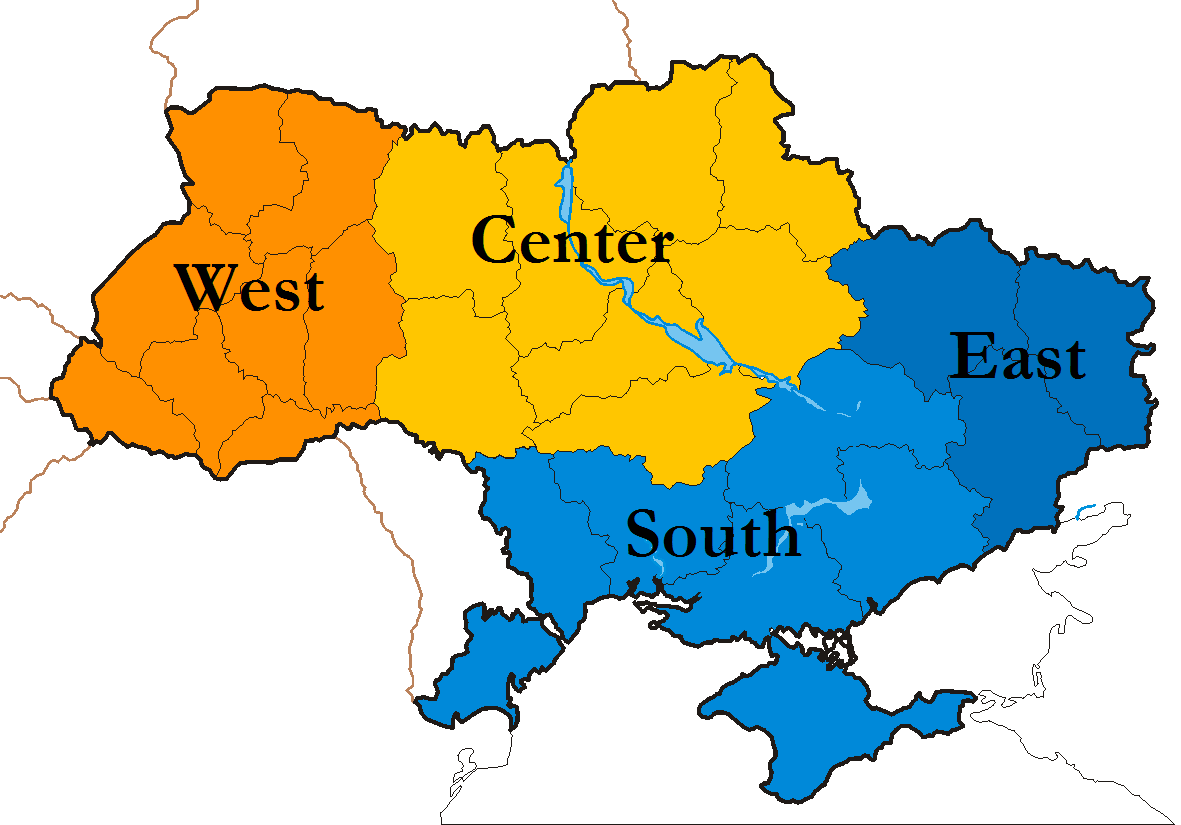

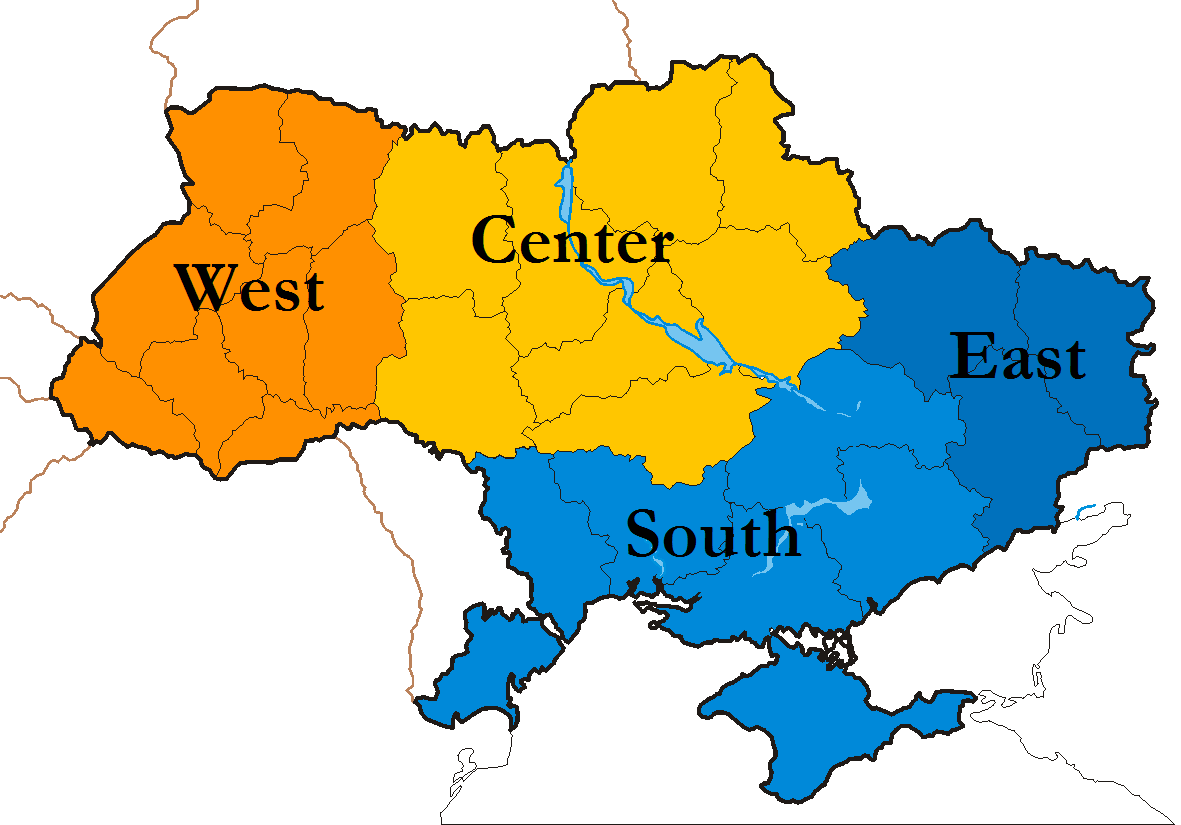

Western Ukraine or West Ukraine ( uk, Західна Україна, Zakhidna Ukraina or , ) is the territory of

Western Ukraine or West Ukraine ( uk, Західна Україна, Zakhidna Ukraina or , ) is the territory of

Carpathian

July 2011). Western Ukraine, takes its roots from the Kingdom of Galicia–Volhynia, a successor of

Following the 14th century

Following the 14th century

Sociological group "RATING", RATING (25 May 2012) and on Joseph StalinСтавлення населення України до постаті Йосипа Сталіна ''Attitude population Ukraine to the figure of Joseph Stalin''

Kyiv International Institute of Sociology (1 March 2013) and more "positive views" on Ukrainian nationalism. A higher percentage of voters in Western Ukraine supported Ukrainian independence in the 1991 Ukrainian independence referendum than in the rest of the country.Ukrainian Nationalism in the 1990s: A Minority Faith

by Andrew Wilson (historian), Andrew Wilson, Cambridge University Press, 1996, (page 128) In a poll conducted by Kyiv International Institute of Sociology in the first half of February 2014 0.7% of polled in West Ukraine believed "Ukraine and Russia must unite into a single state", nationwide this percentage was 12.5, this study didn't include polls in the Luhansk and Donetsk regions of Ukraine.

During Elections in Ukraine, elections voters of Western Oblasts of Ukraine, oblasts (provinces) vote mostly for parties (Our Ukraine–People's Self-Defense Bloc, Our Ukraine, Batkivshchyna) and presidential candidates (Viktor Yushchenko, Yulia Tymoshenko) with a pro-Western and state reform Party platform, platform.Communist and Post-Communist Parties in Europe

In a poll conducted by Kyiv International Institute of Sociology in the first half of February 2014 0.7% of polled in West Ukraine believed "Ukraine and Russia must unite into a single state", nationwide this percentage was 12.5, this study didn't include polls in the Luhansk and Donetsk regions of Ukraine.

During Elections in Ukraine, elections voters of Western Oblasts of Ukraine, oblasts (provinces) vote mostly for parties (Our Ukraine–People's Self-Defense Bloc, Our Ukraine, Batkivshchyna) and presidential candidates (Viktor Yushchenko, Yulia Tymoshenko) with a pro-Western and state reform Party platform, platform.Communist and Post-Communist Parties in Europe

by Uwe Backes and Patrick Moreau, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2008, (page 396)Ukraine right-wing politics: is the genie out of the bottle?

openDemocracy.net (3 January 2011)Eight Reasons Why Ukraine’s Party of Regions Will Win the 2012 Elections

by Taras Kuzio, The Jamestown Foundation (17 October 2012)

UKRAINE: Yushchenko needs Tymoshenko as ally again

by Taras Kuzio, Oxford Analytica (5 October 2007) Of the regions of Western Ukraine, Galicia tends to be the most pro-Western and pro-nationalist area. Volhynia's politics are similar, though not as nationalist or as pro-Western as Galicia's. Bukovina-Chernvisti's electoral politics are more mixed and tempered by the region's significant Romanian minority. Finally, Zakarpattia's electoral politics tend to be more competitive, similar to a Central Ukrainian oblast. This is due to the region's distinct historical and cultural identity as well as the significant Hungarian and Romanian minorities. The politics in the region dominated by such Ukrainian parties as Andriy Baloha's Team, Social Democratic Party of Ukraine (united), pro-Russian separatist movement Podkarpathian Rusyns led by the Russian Orthodox Church bishop Dimitry Sydor and pro-Hungarian Democratic Party.

According to a 2016 survey of religion in Ukraine held by the Razumkov Center, approximately 93% of the population of western Ukraine declared to be believers, while 0.9% declared to non-believers, and 0.2% declared to atheism, atheists.

Of the total population, 97.7% declared to be Christians (57.0% Eastern Orthodox, 30.9% members of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, 4.3% simply Christians, 3.9% members of various Protestantism, Protestant churches, and 1.6% Latin Rite Catholic Church, Catholics), by far more than in all other regions of Ukraine, while 0.2% were Jews. Non-believers and other believers not identifying with any of the listed major religious institutions constituted about 2.1% of the population.

According to a 2016 survey of religion in Ukraine held by the Razumkov Center, approximately 93% of the population of western Ukraine declared to be believers, while 0.9% declared to non-believers, and 0.2% declared to atheism, atheists.

Of the total population, 97.7% declared to be Christians (57.0% Eastern Orthodox, 30.9% members of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, 4.3% simply Christians, 3.9% members of various Protestantism, Protestant churches, and 1.6% Latin Rite Catholic Church, Catholics), by far more than in all other regions of Ukraine, while 0.2% were Jews. Non-believers and other believers not identifying with any of the listed major religious institutions constituted about 2.1% of the population.

Western Ukraine or West Ukraine ( uk, Західна Україна, Zakhidna Ukraina or , ) is the territory of

Western Ukraine or West Ukraine ( uk, Західна Україна, Zakhidna Ukraina or , ) is the territory of Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

linked to the former Kingdom of Galicia–Volhynia, which was part of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi- confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Poland and Lithuania ru ...

, the Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire (german: link=no, Kaiserthum Oesterreich, modern spelling , ) was a Central-Eastern European multinational great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the realms of the Habsburgs. During its existence ...

, Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

and the Second Polish Republic, and came fully under the control of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

(via the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic ( uk, Украї́нська Радя́нська Соціалісти́чна Респу́бліка, ; russian: Украи́нская Сове́тская Социалисти́ческая Респ ...

) only in 1939, following the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact was a non-aggression pact between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union that enabled those powers to partition Poland between them. The pact was signed in Moscow on 23 August 1939 by German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ri ...

. There is no universally accepted definition of the territory's boundaries (see the map, right), but the contemporary Ukrainian administrative regions or Oblasts

An oblast (; ; Cyrillic (in most languages, including Russian and Ukrainian): , Bulgarian: ) is a type of administrative division of Belarus, Bulgaria, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, and Ukraine, as well as the Soviet Union and the Kingdom o ...

of Chernivtsi, Ivano-Frankovsk, Lviv

Lviv ( uk, Львів) is the largest city in western Ukraine, and the seventh-largest in Ukraine, with a population of . It serves as the administrative centre of Lviv Oblast and Lviv Raion, and is one of the main cultural centres of Ukrain ...

, Ternopil

Ternópil ( uk, Тернопіль, Ternopil' ; pl, Tarnopol; yi, טאַרנאָפּל, Tarnopl, or ; he, טארנופול (טַרְנוֹפּוֹל), Tarnopol; german: Tarnopol) is a city in the west of Ukraine. Administratively, Ternopi ...

and Transcarpathia

Transcarpathia may refer to:

Place

* relative term, designating any region beyond the Carpathians (lat. ''trans-'' / beyond, over), depending on a point of observation

* Romanian Transcarpathia, designation for Romanian regions on the inner or ...

(which were part of the former Austro-Hungarian Empire) are nearly always included and the Lutsk

Lutsk ( uk, Луцьк, translit=Lutsk}, ; pl, Łuck ; yi, לוצק, Lutzk) is a city on the Styr River in northwestern Ukraine. It is the administrative center of the Volyn Oblast (province) and the administrative center of the surrounding Lu ...

and Rivne

Rivne (; uk, Рівне ),) also known as Rovno (Russian: Ровно; Polish: Równe; Yiddish: ראָוונע), is a city in western Ukraine. The city is the administrative center of Rivne Oblast (province), as well as the surrounding Rivne Raio ...

Oblasts (parts of the annexed from Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

during its Third Partition) are usually included. It is less common to include the Khmelnytski

Khmelnytskyi ( uk, Хмельни́цький, Khmelnytskyi, ), until 1954 Proskuriv ( uk, Проску́рів, links=no ), is a city in western Ukraine, the administrative center for Khmelnytskyi Oblast (region) and Khmelnytskyi Raion (dist ...

and, especially, the Vinnytsia

Vinnytsia ( ; uk, Вінниця, ; yi, װיניצע) is a city in west-central Ukraine, located on the banks of the Southern Bug.

It is the administrative center of Vinnytsia Oblast and the largest city in the historic region of Podillia. ...

and Zhytomyr

Zhytomyr ( uk, Жито́мир, translit=Zhytomyr ; russian: Жито́мир, Zhitomir ; pl, Żytomierz ; yi, זשיטאָמיר, Zhitomir; german: Schytomyr ) is a city in the north of the western half of Ukraine. It is the administrative ...

Oblasts in this category. It includes several historical regions such as Transcarpathia

Transcarpathia may refer to:

Place

* relative term, designating any region beyond the Carpathians (lat. ''trans-'' / beyond, over), depending on a point of observation

* Romanian Transcarpathia, designation for Romanian regions on the inner or ...

, Halychyna including Pokuttia

Pokuttia, also known as Pokuttya or Pokutia ( uk, Покуття, Pokuttya; pl, Pokucie; german: Pokutien; ro, Pocuția), is a historical area of East-Central Europe, situated between the Dniester and Cheremosh rivers and the Carpathian Moun ...

(eastern portion of Eastern Galicia

Eastern Galicia ( uk, Східна Галичина, Skhidna Galychyna, pl, Galicja Wschodnia, german: Ostgalizien) is a geographical region in Western Ukraine (present day oblasts of Lviv, Ivano-Frankivsk and Ternopil), having also essential h ...

), most of Volhynia

Volhynia (also spelled Volynia) ( ; uk, Воли́нь, Volyn' pl, Wołyń, russian: Волы́нь, Volýnʹ, ), is a historic region in Central and Eastern Europe, between south-eastern Poland, south-western Belarus, and western Ukraine. The ...

, northern Bukovina, and western Podolia

Podolia or Podilia ( uk, Поділля, Podillia, ; russian: Подолье, Podolye; ro, Podolia; pl, Podole; german: Podolien; be, Падолле, Padollie; lt, Podolė), is a historic region in Eastern Europe, located in the west-central ...

. Less often the Western Ukraine includes areas of eastern Volhynia, Podolia, and small portion of northern Bessarabia (eastern part of Chernivtsi Oblast

Chernivtsi Oblast ( uk, Черніве́цька о́бласть, Chernivetska oblast), also referred to as Chernivechchyna ( uk, Чернівеччина) is an oblast (province) in Western Ukraine, consisting of the northern parts of the regio ...

).

Western Ukraine is known for its exceptional natural and cultural heritage, several sites of which are on the List of World Heritage. Architecturally, it includes the fortress of Kamianets, the Old Town of Lviv, the former Residence of Bukovinian and Dalmatian Metropolitans, the Tserkvas, the Khotyn Fortress

The Khotyn Fortress ( uk, Хотинська фортеця, pl, twierdza w Chocimiu, tr, Hotin Kalesi, ro, Cetatea Hotinului) is a fortification complex located on the right bank of the Dniester River in Khotyn, Chernivtsi Oblast (province) ...

and the Pochayiv Lavra. Its landscapes and natural sites also represent a major tourist asset for the region, combining the mountain landscapes of the Ukrainian Carpathians

The Ukrainian Carpathians ( uk, Українські Карпати) are a section of the Eastern Carpathians, within the borders of modern Ukraine. They are located in the southwestern corner of Western Ukraine, within administrative territor ...

and those of the Podolian Upland

The Podolian Upland (Podolian Plateau) or Podillia Upland ( uk, подільська височина, ''podilska vysochyna'') is a highland area in southwestern Ukraine, on the left (northeast) bank of the Dniester River, with small portions in ...

. These include Mount Hoverla, the highest point in Ukraine, Optymistychna Cave

Optymistychna ( uk, Оптимістична: meaning "optimistic", also known as Peschtschera Optimistitscheskaya) is a gypsum cave located near the Ukrainian village of Korolivka, Chortkiv Raion, Ternopil Oblast. Approximately of passageways ...

, the largest in Europe with its 240 km, Bukovel

Bukovel is the largest ski resort in Eastern Europe situated in Ukraine, in Nadvirna Raion, Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast ( province) of western Ukraine. A part of it is in state property. The resort is located almost on the ridge-lines of the Carpat ...

Ski Resort, Synevyr National Park, Carpathian National Park or the Uzhanskyi National Nature Park protecting part of the primary forests included in the Carpathian Biosphere Reserve

Carpathian Biosphere Reserve ( uk, Карпатський біосферний заповідник) is a biosphere reserve that was established as a nature reserve in 1968 and became part of the World Network of Biosphere Reserves of UNESCO in 1 ...

(World Network of Biosphere Reserves

The UNESCO World Network of Biosphere Reserves (WNBR) covers internationally designated protected areas, known as biosphere reserves, which are meant to demonstrate a balanced relationship between people and nature (e.g. encourage sustainable de ...

of UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international cooperation in education, arts, sciences and culture. It ...

UNESCOCarpathian

July 2011). Western Ukraine, takes its roots from the Kingdom of Galicia–Volhynia, a successor of

Kievan Rus'

Kievan Rusʹ, also known as Kyivan Rusʹ ( orv, , Rusĭ, or , , ; Old Norse: ''Garðaríki''), was a state in Eastern and Northern Europe from the late 9th to the mid-13th century.John Channon & Robert Hudson, ''Penguin Historical Atlas of ...

formed in 1199 after the weakening of Kievan Rus' and attacks from the Golden Horde

The Golden Horde, self-designated as Ulug Ulus, 'Great State' in Turkic, was originally a Mongol and later Turkicized khanate established in the 13th century and originating as the northwestern sector of the Mongol Empire. With the fragme ...

. As of 1349, both Kievan Rus'

Kievan Rusʹ, also known as Kyivan Rusʹ ( orv, , Rusĭ, or , , ; Old Norse: ''Garðaríki''), was a state in Eastern and Northern Europe from the late 9th to the mid-13th century.John Channon & Robert Hudson, ''Penguin Historical Atlas of ...

and Kingdom of Galicia–Volhynia lost their independence and Ukrainian territories fell under the control of neighboring states. Firstly Ukraine was incorporated into the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi- confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Poland and Lithuania ru ...

, and later Ukraine was divided between the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (western and part of central Ukraine) and the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

(eastern and the remainder of central Ukraine). After the Partitions of Poland, western Ukrainian regions became part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, while central and eastern Ukrainian regions were still under Russian control. In 1918, after World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, Ukrainian territories that had been under Russian control proclaimed independence as the Ukrainian People's Republic

The Ukrainian People's Republic (UPR), or Ukrainian National Republic (UNR), was a country in Eastern Europe that existed between 1917 and 1920. It was declared following the February Revolution in Russia by the First Universal. In March 1 ...

, while western Ukrainian territories that had been part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire proclaimed their independence as the West Ukrainian People's Republic

The West Ukrainian People's Republic (WUPR) or West Ukrainian National Republic (WUNR), known for part of its existence as the Western Oblast of the Ukrainian People's Republic, was a short-lived polity that controlled most of Eastern Gali ...

. On January 22, 1919, both states signed the Unification Act but were divided again between Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

and the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

. Later, as a result of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact was a non-aggression pact between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union that enabled those powers to partition Poland between them. The pact was signed in Moscow on 23 August 1939 by German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ri ...

, the Soviet Union incorporated western Ukraine into the Ukrainian SSR. Not until the 1991 Declaration of Independence of Ukraine did Ukraine gain its independence; the Dissolution of the Soviet Union followed soon afterward. Nowadays, Russian cultural influence in the Ukrainian West is negligible. Indeed, Moscow only obtained control over the territory in the 20th century, namely, during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

when it was annexed to the Soviet Union following the partitioning of Poland and the Carpathian Ruthenia (today Zakarpattia) after World War II. Its historical background makes Western Ukraine uniquely different from the rest of the country, and contributes to its distinctive character today.

The city of Lviv

Lviv ( uk, Львів) is the largest city in western Ukraine, and the seventh-largest in Ukraine, with a population of . It serves as the administrative centre of Lviv Oblast and Lviv Raion, and is one of the main cultural centres of Ukrain ...

is the main cultural center of the region and was the historical capital of the Kingdom of Galicia–Volhynia. Other important cities are Buchach

Buchach ( uk, Бучач; pl, Buczacz; yi, בעטשאָטש, Betshotsh or (Bitshotsh); he, בוצ'אץ' ''Buch'ach''; german: Butschatsch; tr, Bucaş) is a city located on the Strypa River (a tributary of the Dniester) in Chortkiv Raion of T ...

, Chernivtsi, Drohobych

Drohobych ( uk, Дрого́бич, ; pl, Drohobycz; yi, דראָהאָביטש;) is a city of regional significance in Lviv Oblast, Ukraine. It is the administrative center of Drohobych Raion and hosts the administration of Drohobych urban h ...

, Halych

Halych ( uk, Га́лич ; ro, Halici; pl, Halicz; russian: Га́лич, Galich; german: Halytsch, ''Halitsch'' or ''Galitsch''; yi, העליטש) is a historic city on the Dniester River in western Ukraine. The city gave its name to the P ...

(hence, Halychyna), Ivano-Frankivsk, Khotyn

Khotyn ( uk, Хотин, ; ro, Hotin, ; see other names) is a city in Dnistrovskyi Raion, Chernivtsi Oblast of western Ukraine and is located south-west of Kamianets-Podilskyi. It hosts the administration of Khotyn urban hromada, one of t ...

, Lutsk

Lutsk ( uk, Луцьк, translit=Lutsk}, ; pl, Łuck ; yi, לוצק, Lutzk) is a city on the Styr River in northwestern Ukraine. It is the administrative center of the Volyn Oblast (province) and the administrative center of the surrounding Lu ...

, Mukachevo

Mukachevo ( uk, Мукачево, ; hu, Munkács; see name section) is a city in the valley of the Latorica river in Zakarpattia Oblast (province), in Western Ukraine. Serving as the administrative center of Mukachevo Raion (district), the city ...

, Rivne

Rivne (; uk, Рівне ),) also known as Rovno (Russian: Ровно; Polish: Równe; Yiddish: ראָוונע), is a city in western Ukraine. The city is the administrative center of Rivne Oblast (province), as well as the surrounding Rivne Raio ...

, Ternopil

Ternópil ( uk, Тернопіль, Ternopil' ; pl, Tarnopol; yi, טאַרנאָפּל, Tarnopl, or ; he, טארנופול (טַרְנוֹפּוֹל), Tarnopol; german: Tarnopol) is a city in the west of Ukraine. Administratively, Ternopi ...

and Uzhhorod

Uzhhorod ( uk, У́жгород, , ; ) is a city and municipality on the river Uzh in western Ukraine, at the border with Slovakia and near the border with Hungary. The city is approximately equidistant from the Baltic, the Adriatic and the ...

.

History

Following the 14th century

Following the 14th century Galicia–Volhynia Wars

The Galicia–Volhynia Wars were several wars fought in the years 1340–1392 over the succession in the Kingdom of Galicia–Volhynia, also known as Ruthenia. After Yuri II Boleslav was poisoned by local Ruthenian nobles in 1340, both the Grand ...

, most of the region was transferred to the Crown of Poland

The Crown of the Kingdom of Poland ( pl, Korona Królestwa Polskiego; Latin: ''Corona Regni Poloniae''), known also as the Polish Crown, is the common name for the historic Late Middle Ages territorial possessions of the King of Poland, includi ...

under Casimir the Great, who received the lands legally by a downward agreement in 1340 after his nephew's death, Bolesław-Jerzy II. The eastern Volhynia

Volhynia (also spelled Volynia) ( ; uk, Воли́нь, Volyn' pl, Wołyń, russian: Волы́нь, Volýnʹ, ), is a historic region in Central and Eastern Europe, between south-eastern Poland, south-western Belarus, and western Ukraine. The ...

and most of Podolia

Podolia or Podilia ( uk, Поділля, Podillia, ; russian: Подолье, Podolye; ro, Podolia; pl, Podole; german: Podolien; be, Падолле, Padollie; lt, Podolė), is a historic region in Eastern Europe, located in the west-central ...

was added to the territory of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania

The Grand Duchy of Lithuania was a European state that existed from the 13th century to 1795, when the territory was partitioned among the Russian Empire, the Kingdom of Prussia, and the Habsburg Empire of Austria. The state was founded by Lit ...

by Lubart.

The territory of Bukovina was part of Moldavia

Moldavia ( ro, Moldova, or , literally "The Country of Moldavia"; in Romanian Cyrillic alphabet, Romanian Cyrillic: or ; chu, Землѧ Молдавскаѧ; el, Ἡγεμονία τῆς Μολδαβίας) is a historical region and for ...

since its formation by voivode Dragoș, who was departed by the Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from the Middle Ages into the 20th century. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the coronation of the first king Stephen ...

, during the 14th century.

After the 18th century partitions of Poland (Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi- confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Poland and Lithuania ru ...

), the territory was split between the Habsburg monarchy and the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

. The modern south-western part of Western Ukraine became the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria

The Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria,, ; pl, Królestwo Galicji i Lodomerii, ; uk, Королівство Галичини та Володимирії, Korolivstvo Halychyny ta Volodymyrii; la, Rēgnum Galiciae et Lodomeriae also known as ...

, after 1804 crownland of the Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire (german: link=no, Kaiserthum Oesterreich, modern spelling , ) was a Central-Eastern European multinational great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the realms of the Habsburgs. During its existence ...

. Its northern flank with the cities of Lutsk

Lutsk ( uk, Луцьк, translit=Lutsk}, ; pl, Łuck ; yi, לוצק, Lutzk) is a city on the Styr River in northwestern Ukraine. It is the administrative center of the Volyn Oblast (province) and the administrative center of the surrounding Lu ...

and Rivne

Rivne (; uk, Рівне ),) also known as Rovno (Russian: Ровно; Polish: Równe; Yiddish: ראָוונע), is a city in western Ukraine. The city is the administrative center of Rivne Oblast (province), as well as the surrounding Rivne Raio ...

was acquired in 1795 by Imperial Russia following the third and final partition of Poland. Throughout its existence Russian Poland

Congress Poland, Congress Kingdom of Poland, or Russian Poland, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland, was a polity created in 1815 by the Congress of Vienna as a semi-autonomous Polish state, a successor to Napoleon's Duchy of Warsaw. It w ...

was marred with violence and intimidation, beginning with the 1794 massacres, imperial land-theft and the deportations of the November and January Uprisings. By contrast, the Austrian Partition

The Austrian Partition ( pl, zabór austriacki) comprise the former territories of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth acquired by the Habsburg monarchy during the Partitions of Poland in the late 18th century. The three partitions were conduct ...

with its Sejm of the Land in the cities of Lviv

Lviv ( uk, Львів) is the largest city in western Ukraine, and the seventh-largest in Ukraine, with a population of . It serves as the administrative centre of Lviv Oblast and Lviv Raion, and is one of the main cultural centres of Ukrain ...

and Stanyslaviv (Ivano-Frankivsk) was freer politically perhaps because it had a lot less to offer economically. Imperial Austria did not persecute Ukrainian organizations. In later years, Austria-Hungary de facto encouraged the existence of Ukrainian political organizations in order to counterbalance the influence of Polish culture in Galicia. The southern half of West Ukraine remained under Austrian administration until the collapse of the House of Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

at the end of World War One in 1918.

In 1775, following the Russo-Turkish Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca

The Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca ( tr, Küçük Kaynarca Antlaşması; russian: Кючук-Кайнарджийский мир), formerly often written Kuchuk-Kainarji, was a peace treaty signed on 21 July 1774, in Küçük Kaynarca (today Kayn ...

, Moldavia lost to the Habsburg monarchy its northwestern part, which became known as Bukovina, and remained under Austrian administration until 1918.

Interbellum and World War II

Following the defeat ofUkrainian People's Republic

The Ukrainian People's Republic (UPR), or Ukrainian National Republic (UNR), was a country in Eastern Europe that existed between 1917 and 1920. It was declared following the February Revolution in Russia by the First Universal. In March 1 ...

(1918) in the Soviet–Ukrainian War of 1921, Western Ukraine was partitioned by the Treaty of Riga

The Peace of Riga, also known as the Treaty of Riga ( pl, Traktat Ryski), was signed in Riga on 18 March 1921, among Poland, Soviet Russia (acting also on behalf of Soviet Belarus) and Soviet Ukraine. The treaty ended the Polish–Soviet War.

...

between Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, and the Soviet Russia acting on behalf of the Soviet Belarus and the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic ( uk, Украї́нська Радя́нська Соціалісти́чна Респу́бліка, ; russian: Украи́нская Сове́тская Социалисти́ческая Респ ...

with capital in Kharkiv

Kharkiv ( uk, wikt:Харків, Ха́рків, ), also known as Kharkov (russian: Харькoв, ), is the second-largest List of cities in Ukraine, city and List of hromadas of Ukraine, municipality in Ukraine.Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

gained control over the entire territory of the short-lived Ukrainian People's Republic east of the border with Poland.Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States: 1999Routledge

Routledge () is a British multinational publisher. It was founded in 1836 by George Routledge, and specialises in providing academic books, journals and online resources in the fields of the humanities, behavioural science, education, law ...

, 1999, (page 849) In the Interbellum

In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days), the end of the First World War to the beginning of the Second World War. The interwar period was relative ...

most of the territory of today's Western Ukraine belonged to the Second Polish Republic. Territories such as Bukovina and Carpatho-Ukraine

Carpatho-Ukraine or Carpathian Ukraine ( uk, Карпа́тська Украї́на, Karpats’ka Ukrayina, ) was an autonomous region within the Second Czechoslovak Republic, created in December 1938 by renaming Subcarpathian Rus' whose full ...

belonged to Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Moldova to the east, and ...

and Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

, respectively.

At the onset of Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa (german: link=no, Unternehmen Barbarossa; ) was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and many of its Axis allies, starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during the Second World War. The operation, code-named after ...

by Nazi Germany, the region became occupied by Nazi Germany in 1941. The southern half of West Ukraine was incorporated into the semi-colonial '' Distrikt Galizien'' (District of Galicia) created on August 1, 1941 (Document No. 1997-PS of July 17, 1941 by Adolf Hitler) with headquarters in Chełm Lubelski, bordering district of General Government to the west. Its northern part (Volhynia

Volhynia (also spelled Volynia) ( ; uk, Воли́нь, Volyn' pl, Wołyń, russian: Волы́нь, Volýnʹ, ), is a historic region in Central and Eastern Europe, between south-eastern Poland, south-western Belarus, and western Ukraine. The ...

) was assigned to the ''Reichskommissariat Ukraine

During World War II, (abbreviated as RKU) was the civilian occupation regime () of much of Nazi German-occupied Ukraine (which included adjacent areas of modern-day Belarus and pre-war Second Polish Republic). It was governed by the Reich Min ...

'' formed in September 1941. Notably, the District of Galicia was a separate administrative unit from the actual ''Reichskommissariat Ukraine'' with capital in Rivne

Rivne (; uk, Рівне ),) also known as Rovno (Russian: Ровно; Polish: Równe; Yiddish: ראָוונע), is a city in western Ukraine. The city is the administrative center of Rivne Oblast (province), as well as the surrounding Rivne Raio ...

. They were not connected with each other politically for Nazi Germans. The division was administrative and conditional, in his book "From Putyvl to the Carpathian" Sydir Kovpak

Sydir Artemovych Kovpak ( uk, Сидір Артемович Ковпак; russian: Си́дор Арте́мьевич Ковпа́к, ), (June 7, 1887December 11, 1967) was one of the partisan leaders of the Soviet partisans in Ukraine during t ...

never mentioned about any border-like divisions. Bukovina was controlled by the pro-Nazi Kingdom of Romania.

Post-War

After the defeat of Germany in World War II, in May 1945 the Soviet Union incorporated all territories of current Western Ukraine into the Ukrainian SSR. Between 1944 and 1946, apopulation exchange between Poland and Soviet Ukraine

The population exchange between Poland and Soviet Ukraine at the end of World War II was based on a treaty signed on 9 September 1944 by the Ukrainian SSR with the newly-formed Polish Committee of National Liberation (PKWN). The exchange stipulat ...

occurred in which all ethnic Poles and Jews who had Polish citizenship before September 17, 1939 (date of the Soviet Invasion of Poland) were transferred to post-war Poland and all ethnic Ukrainians to the Ukrainian SSR, in accordance with the resolutions of the Yalta and Tehran conferences and the plans about the new Poland–Ukraine border.

Recent history

During the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Russia attacked Ukrainian military facility near the city ofLviv

Lviv ( uk, Львів) is the largest city in western Ukraine, and the seventh-largest in Ukraine, with a population of . It serves as the administrative centre of Lviv Oblast and Lviv Raion, and is one of the main cultural centres of Ukrain ...

, in Western Ukraine with cruise missiles. Later in March Russia performed missile attacks on oil depots in Lviv

Lviv ( uk, Львів) is the largest city in western Ukraine, and the seventh-largest in Ukraine, with a population of . It serves as the administrative centre of Lviv Oblast and Lviv Raion, and is one of the main cultural centres of Ukrain ...

, Dubno

Dubno ( uk, Ду́бно) is a city and municipality located on the Ikva River in Rivne Oblast (province) of western Ukraine. It serves as the administrative center of Dubno Raion (district). The city is located on intersection of two major ...

and Lutsk

Lutsk ( uk, Луцьк, translit=Lutsk}, ; pl, Łuck ; yi, לוצק, Lutzk) is a city on the Styr River in northwestern Ukraine. It is the administrative center of the Volyn Oblast (province) and the administrative center of the surrounding Lu ...

.

Divisions

Western Ukraine includes such lands as Zakarpattia,Volyn

Volhynia (also spelled Volynia) ( ; uk, Воли́нь, Volyn' pl, Wołyń, russian: Волы́нь, Volýnʹ, ), is a historic region in Central and Eastern Europe, between south-eastern Poland, south-western Belarus, and western Ukraine. The ...

, Halychyna ( Prykarpattia, Pokuttia

Pokuttia, also known as Pokuttya or Pokutia ( uk, Покуття, Pokuttya; pl, Pokucie; german: Pokutien; ro, Pocuția), is a historical area of East-Central Europe, situated between the Dniester and Cheremosh rivers and the Carpathian Moun ...

), Bukovina, Polissia, and Podillia

Podolia or Podilia ( uk, Поділля, Podillia, ; russian: Подолье, Podolye; ro, Podolia; pl, Podole; german: Podolien; be, Падолле, Padollie; lt, Podolė), is a historic region in Eastern Europe, located in the west-central ...

. Note that sometimes Khmelnytsky region is considered a part of the central Ukraine as it is mostly lies within the western Podillya.

The history of Western Ukraine is closely associated with the history of the following lands:

* Easternmost Bukovina, historical region of Central Europe in official use since 1775, controlled by the Kingdom of Romania

The Kingdom of Romania ( ro, Regatul României) was a constitutional monarchy that existed in Romania from 13 March ( O.S.) / 25 March 1881 with the crowning of prince Karl of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen as King Carol I (thus beginning the Romanian ...

after World War I, and half of it ceded to the USSR in 1940 (reconfirmed by Paris Peace Treaties, 1947)

* Eastern Galicia

Eastern Galicia ( uk, Східна Галичина, Skhidna Galychyna, pl, Galicja Wschodnia, german: Ostgalizien) is a geographical region in Western Ukraine (present day oblasts of Lviv, Ivano-Frankivsk and Ternopil), having also essential h ...

( uk, Halychyna), once a small kingdom with Lodomeria (1914), province of the Austrian Empire until the dissolution of Austria-Hungary in 1918. See also: crownland of the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria

The Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria,, ; pl, Królestwo Galicji i Lodomerii, ; uk, Королівство Галичини та Володимирії, Korolivstvo Halychyny ta Volodymyrii; la, Rēgnum Galiciae et Lodomeriae also known as ...

* Red Ruthenia since medieval times in the area known today as Eastern Galicia.

* West Ukrainian People's Republic

The West Ukrainian People's Republic (WUPR) or West Ukrainian National Republic (WUNR), known for part of its existence as the Western Oblast of the Ukrainian People's Republic, was a short-lived polity that controlled most of Eastern Gali ...

declared in late 1918 until early 1919 and claiming half of Galicia with mostly Polish city dwellers (historical sense).

* Carpatho-Ukraine

Carpatho-Ukraine or Carpathian Ukraine ( uk, Карпа́тська Украї́на, Karpats’ka Ukrayina, ) was an autonomous region within the Second Czechoslovak Republic, created in December 1938 by renaming Subcarpathian Rus' whose full ...

region within Czechoslovakia (1939) under Hungarian control until the Nazi occupation of Hungary in 1944.

* General Government of Galicia and Bukovina captured from Austria-Hungary during World War I.

* Ținutul Suceava (Kingdom of Romania

The Kingdom of Romania ( ro, Regatul României) was a constitutional monarchy that existed in Romania from 13 March ( O.S.) / 25 March 1881 with the crowning of prince Karl of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen as King Carol I (thus beginning the Romanian ...

)

* Volhynia

Volhynia (also spelled Volynia) ( ; uk, Воли́нь, Volyn' pl, Wołyń, russian: Волы́нь, Volýnʹ, ), is a historic region in Central and Eastern Europe, between south-eastern Poland, south-western Belarus, and western Ukraine. The ...

, historic region straddling Poland, Ukraine, and Belarus to the north. The alternate name for the region today is Lodomeria after the city of Volodymyr. See also: Polish unofficial term Kresy (Borderlands, 1918–1939) that includes the West Belarus as well as Volhynia.

* Zakarpattia or Carpathian Ruthenia presently in the Zakarpattia Oblast of western Ukraine.

Administrative and historical divisions

Cultural characteristics

Differences with rest of Ukraine

Ukrainian language, Ukrainian is the dominant language in the region. Back in the schools of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, Ukrainian SSR learning Russian language, Russian was mandatory; currently, in modern Ukraine, in schools with Ukrainian as the language of instruction, classes in Russian and in other minority languages are offered.Serhy Yekelchyk ''Ukraine: Birth of a Modern Nation'', Oxford University Press (2007), In terms of religion, the majority of adherents share the Byzantine Rite of Christianity as in the rest of Ukraine, but due to the region escaping the 1920s and 1930s Persecution of Christians in the Soviet Union, Soviet persecution, a notably greater church adherence and belief in religion's role in society is present. Due to the complex History of Christianity in Ukraine, post-independence religious confrontation of several church groups and their adherents, the historical influence played a key role in shaping the present loyalty of Western Ukraine's faithful. In Galician provinces, the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church has the strongest following in the country, and the largest share of property and faithful. In the remaining regions: Volhynia, Bukovina and Transcarpathia the Eastern Orthodox Church, Orthodoxy is prevalent. Outside of Western Ukraine the greatest in terms of Church property, clergy, and according to some estimates, faithful, is the Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate). In the listed regions (and in particular among the Orthodox faithful in Galicia), this position is notably weaker, as the main rivals, the Ukrainian Orthodox Church – Kyiv Patriarchate and the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church, have a far greater influence. Within the lands of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, the largest Eastern Catholic Church, priests' children often became priests and married within their social group, establishing a Eastern Catholic clergy in Ukraine, tightly-knit hereditary caste. Noticeable cultural differences in the region (compared with the rest of Ukraine especially Southern Ukraine and Eastern Ukraine) are more "negative views" on the Russian language in Ukraine, Russian languageThe language question, the results of recent research in 2012Sociological group "RATING", RATING (25 May 2012) and on Joseph StalinСтавлення населення України до постаті Йосипа Сталіна ''Attitude population Ukraine to the figure of Joseph Stalin''

Kyiv International Institute of Sociology (1 March 2013) and more "positive views" on Ukrainian nationalism. A higher percentage of voters in Western Ukraine supported Ukrainian independence in the 1991 Ukrainian independence referendum than in the rest of the country.Ukrainian Nationalism in the 1990s: A Minority Faith

by Andrew Wilson (historian), Andrew Wilson, Cambridge University Press, 1996, (page 128)

In a poll conducted by Kyiv International Institute of Sociology in the first half of February 2014 0.7% of polled in West Ukraine believed "Ukraine and Russia must unite into a single state", nationwide this percentage was 12.5, this study didn't include polls in the Luhansk and Donetsk regions of Ukraine.

During Elections in Ukraine, elections voters of Western Oblasts of Ukraine, oblasts (provinces) vote mostly for parties (Our Ukraine–People's Self-Defense Bloc, Our Ukraine, Batkivshchyna) and presidential candidates (Viktor Yushchenko, Yulia Tymoshenko) with a pro-Western and state reform Party platform, platform.Communist and Post-Communist Parties in Europe

In a poll conducted by Kyiv International Institute of Sociology in the first half of February 2014 0.7% of polled in West Ukraine believed "Ukraine and Russia must unite into a single state", nationwide this percentage was 12.5, this study didn't include polls in the Luhansk and Donetsk regions of Ukraine.

During Elections in Ukraine, elections voters of Western Oblasts of Ukraine, oblasts (provinces) vote mostly for parties (Our Ukraine–People's Self-Defense Bloc, Our Ukraine, Batkivshchyna) and presidential candidates (Viktor Yushchenko, Yulia Tymoshenko) with a pro-Western and state reform Party platform, platform.Communist and Post-Communist Parties in Europeby Uwe Backes and Patrick Moreau, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2008, (page 396)Ukraine right-wing politics: is the genie out of the bottle?

openDemocracy.net (3 January 2011)

by Taras Kuzio, The Jamestown Foundation (17 October 2012)

UKRAINE: Yushchenko needs Tymoshenko as ally again

by Taras Kuzio, Oxford Analytica (5 October 2007)

Demographics

Religion

See also

* Dnieper Ukraine * Western Belorussia, Western Belarus * Wild FieldsNotes and references

External links

* * {{Authority control Geographic regions of Ukraine Carpathian Ruthenia