Wedding of Nora Robinson and Alexander Kirkman Finlay on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The wedding of Nora Augusta Maud Robinson with Alexander Kirkman Finlay, of Glenormiston, was solemnised in

The wedding of Nora Augusta Maud Robinson with Alexander Kirkman Finlay, of Glenormiston, was solemnised in

The first carriages to arrive at the church brought Lady Robinson, Mrs. St. John, Captain St. John, A.D.C., and H. S. Lyttleton, private secretary. The following carriage contained the bridegroom and Captain Standish (chief-commissioner of police in Victoria) as

The first carriages to arrive at the church brought Lady Robinson, Mrs. St. John, Captain St. John, A.D.C., and H. S. Lyttleton, private secretary. The following carriage contained the bridegroom and Captain Standish (chief-commissioner of police in Victoria) as

The wedding breakfast took place at

The wedding breakfast took place at

The wedding party consisted of the bride and bride groom, the bridesmaids—Miss Nereda Robinson and Miss Neva St. John—the governor, the Lady Robinson, Captain St. John, A.D.C., Mrs St. John, and H. Littleton, private secretary; Sir

The wedding party consisted of the bride and bride groom, the bridesmaids—Miss Nereda Robinson and Miss Neva St. John—the governor, the Lady Robinson, Captain St. John, A.D.C., Mrs St. John, and H. Littleton, private secretary; Sir

Alexander Kirkman Finlay was the second son of Alexander Struthers Finlay of Castle Toward, Argyllshire and Mrs Finlay in

Alexander Kirkman Finlay was the second son of Alexander Struthers Finlay of Castle Toward, Argyllshire and Mrs Finlay in

The groom returned to Castle Toward, his family home in Scotland, where he died on 29 July 1883 from "phthisis" (now known as

The groom returned to Castle Toward, his family home in Scotland, where he died on 29 July 1883 from "phthisis" (now known as

The wedding of Nora Augusta Maud Robinson with Alexander Kirkman Finlay, of Glenormiston, was solemnised in

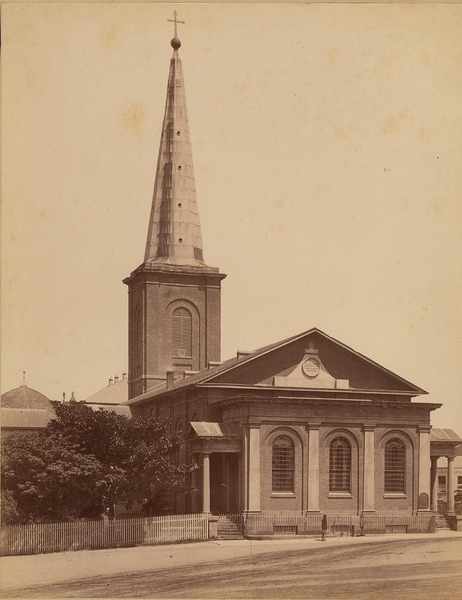

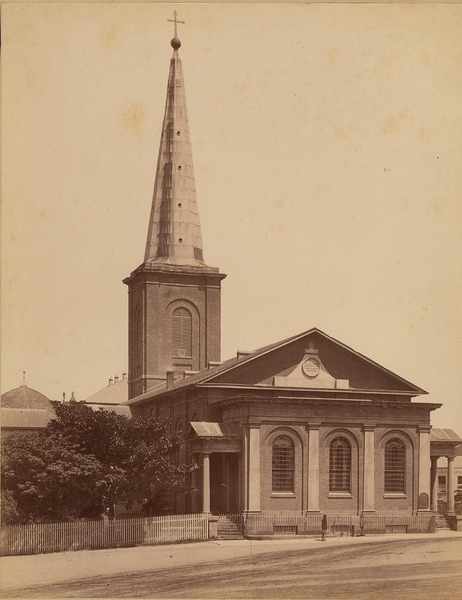

The wedding of Nora Augusta Maud Robinson with Alexander Kirkman Finlay, of Glenormiston, was solemnised in St James' Church, Sydney

St James' Church, commonly known as St James', King Street, is an Australian heritage-listed Anglican parish church located at 173 King Street, in the Sydney central business district in New South Wales. Consecrated in February 1824 and named ...

, on Wednesday, 7 August 1878 by the Rev. Canon Allwood, assisted by Rev. Hough. The bride was the second daughter of the governor of New South Wales

The governor of New South Wales is the viceregal representative of the Australian monarch, King Charles III, in the state of New South Wales. In an analogous way to the governor-general of Australia at the national level, the governors of the ...

, Sir Hercules Robinson, GCMG

The Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George is a British order of chivalry founded on 28 April 1818 by George IV, Prince of Wales, while he was acting as prince regent for his father, King George III.

It is named in honour ...

, and his wife. The groom, owner of Glenormiston, a large station in Victoria

Victoria most commonly refers to:

* Victoria (Australia), a state of the Commonwealth of Australia

* Victoria, British Columbia, provincial capital of British Columbia, Canada

* Victoria (mythology), Roman goddess of Victory

* Victoria, Seychelle ...

, was the second son of Alexander Struthers Finlay

Alexander Struthers Finlay (20 July 1807 – 9 June 1886) was a Scottish Liberal Party politician who served as the Member of Parliament (MP) for Argyllshire 1857–68.

He was a Deputy Lieutenant for Argyllshire and Buteshire and a magistrate ...

, of Castle Toward, Argyleshire, Scotland.

As this was only the second vice-regal

A viceroy () is an official who reigns over a polity in the name of and as the representative of the monarch of the territory. The term derives from the Latin prefix ''vice-'', meaning "in the place of" and the French word ''roy'', meaning "k ...

wedding to take place in the colony, it generated enormous public interest. The crowd, estimated at between 8,000 and 10,000, thronged the streets outside the church and a large body of police had trouble preserving order. The wedding was attended by the most important members of Sydney society at the time - leaders, administrators, officials, legislators, naval officers, lawyers and aristocrats, many of whom had Scottish connections. There was extensive coverage in the press around the country, including in ''The Sydney Morning Herald

''The Sydney Morning Herald'' (''SMH'') is a daily compact newspaper published in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, and owned by Nine. Founded in 1831 as the ''Sydney Herald'', the ''Herald'' is the oldest continuously published newspaper ...

'', ''The Queanbeyan Age

''The Queanbeyan Age'' is a weekly newspaper based in Queanbeyan, New South Wales, Australia. It has had a number of title changes throughout its publication history. First published on 15 September 1860 by John Gale and his brother, Peter F ...

'', the ''South Australian Register

''The Register'', originally the ''South Australian Gazette and Colonial Register'', and later ''South Australian Register,'' was South Australia's first newspaper. It was first published in London in June 1836, moved to Adelaide in 1837, and f ...

'', the ''Australian Town and Country Journal

Australian(s) may refer to:

Australia

* Australia, a country

* Australians, citizens of the Commonwealth of Australia

** European Australians

** Anglo-Celtic Australians, Australians descended principally from British colonists

** Aboriginal Aus ...

'', ''The Argus'', ''The Wagga Wagga Daily Advertiser'' and the ''Riverine Herald

''The Riverine Herald'' is a tri-weekly newspaper based in Echuca in Victoria's Goulburn Valley, servicing the Echuca-Moama area. The paper is owned by McPherson Media Group.

Origins

The newspaper was founded at Echuca on 1 July 1863, with its ...

''.

Wedding service

The first carriages to arrive at the church brought Lady Robinson, Mrs. St. John, Captain St. John, A.D.C., and H. S. Lyttleton, private secretary. The following carriage contained the bridegroom and Captain Standish (chief-commissioner of police in Victoria) as

The first carriages to arrive at the church brought Lady Robinson, Mrs. St. John, Captain St. John, A.D.C., and H. S. Lyttleton, private secretary. The following carriage contained the bridegroom and Captain Standish (chief-commissioner of police in Victoria) as best man

A groomsman or usher is one of the male attendants to the groom in a wedding ceremony and performs the first speech at the wedding. Usually, the groom selects close friends and relatives to serve as groomsmen, and it is considered an honor to be ...

. The carriage containing the bride, her father, (the governor) and the bridesmaids (Miss Nereda Robinson and Miss Neva St. John) came immediately afterwards. The people cheered the arrival of each carriage.

The service was performed by Canon Allwood, who was assisted by Rev. Hough. Inside St James', the church was decorated with plants and flowers, which had come from the Botanic Gardens

A botanical garden or botanic gardenThe terms ''botanic'' and ''botanical'' and ''garden'' or ''gardens'' are used more-or-less interchangeably, although the word ''botanic'' is generally reserved for the earlier, more traditional gardens, an ...

, including "palms, tree ferns, crotons, dracoenas, dieffenbachia

''Dieffenbachia'' , commonly known as dumb cane or leopard lily, is a genus of tropical flowering plants in the family Araceae. It is native to the New World Tropics from Mexico and the West Indies south to Argentina. Some species are widely cul ...

, and pandanas, and immediately in front was a number of richest orchids and ferns. Among the former were vandas, graccelebium, and a Graeceum sesquapedale and superpetam, which will at once be recognised by florists as among the richest we have here ..."

The Robinson-Finlay bridal party arrived at the church shortly before 1 o'clock. The bridegroom was accompanied by his best man, Captain Standish, Chief Commissioner of Police in Victoria, and the bride entered the church leaning on the arm of her father, the governor of New South Wales. The service was accompanied by music provided by a choir and the organ and the bridal couple departing to the music of a wedding march

Music is often played at wedding celebrations, including during the ceremony and at festivities before or after the event. The music can be performed live by instrumentalists or vocalists or may use pre-recorded songs, depending on the format o ...

. The bells of the nearby St Mary's Cathedral were rung (St James' had no bells at the time).

Wedding breakfast and honeymoon

The wedding breakfast took place at

The wedding breakfast took place at Government House

Government House is the name of many of the official residences of governors-general, governors and lieutenant-governors in the Commonwealth and the remaining colonies of the British Empire. The name is also used in some other countries.

Gover ...

where the toast to the bride and groom was given by Sir Alfred Stephen, followed by other toasts.

The carriage containing the couple left Government House at about four o'clock, the travelling costume of the bride being a princess dress of dark-brown silk trimmed with blue, with bonnet and parasol of the same material." They spent their honeymoon

A honeymoon is a vacation taken by newlyweds immediately after their wedding, to celebrate their marriage. Today, honeymoons are often celebrated in destinations considered exotic or romantic. In a similar context, it may also refer to the phase ...

at Eurimbla, Botany

Botany, also called , plant biology or phytology, is the science of plant life and a branch of biology. A botanist, plant scientist or phytologist is a scientist who specialises in this field. The term "botany" comes from the Ancient Greek w ...

, at a house lent to them.

Wedding party

The wedding party consisted of the bride and bride groom, the bridesmaids—Miss Nereda Robinson and Miss Neva St. John—the governor, the Lady Robinson, Captain St. John, A.D.C., Mrs St. John, and H. Littleton, private secretary; Sir

The wedding party consisted of the bride and bride groom, the bridesmaids—Miss Nereda Robinson and Miss Neva St. John—the governor, the Lady Robinson, Captain St. John, A.D.C., Mrs St. John, and H. Littleton, private secretary; Sir John Hay

John Milton Hay (October 8, 1838July 1, 1905) was an American statesman and official whose career in government stretched over almost half a century. Beginning as a private secretary and assistant to Abraham Lincoln, Hay's highest office was Un ...

and Lady Hay, Sir George W. Allen and Lady Allen, Sir Alfred

Alfred may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

*''Alfred J. Kwak'', Dutch-German-Japanese anime television series

* ''Alfred'' (Arne opera), a 1740 masque by Thomas Arne

* ''Alfred'' (Dvořák), an 1870 opera by Antonín Dvořák

*"Alfred (Interlu ...

and Lady Stephen, Sir George and Lady Innes, Sir William and Lady Manning, Commodore Hoskins, R.N., and several officers of HMS ''Wolverine''. Commodore Hoskins had married Dorothea Ann Eliza Robinson, daughter of Sir George Stamp Robinson, 7th Baronet (1797–1873). Miss Deas-Thompson was still a parishioner of St James' in 1900.

Attire

The bride wore a train of the rich old Englishbrocatelle

Brocatelle is a silk-rich fabric with heavy brocade designs. The material is characterized by satin effects standing out in relief in the warp against a flat ground. It is produced with jacquard weave by using silk, rayon, cotton, or many sy ...

over white ottoman silk

Silk is a natural protein fiber, some forms of which can be woven into textiles. The protein fiber of silk is composed mainly of fibroin and is produced by certain insect larvae to form cocoons. The best-known silk is obtained from the coc ...

, trimmed with flounces of Brussels lace

Brussels lace is a type of pillow lace that originated in and around Brussels."Brussels." ''The Oxford English Dictionary''. 2nd ed. 1989. The term "Brussels lace" has been broadly used for any lace from Brussels; however, strictly interpreted, ...

and crepe-leece. Her head dress comprised a very long soft tulle

Tulle (; ) is a commune in central France. It is the third-largest town in the former region of Limousin and is the capital of the department of Corrèze, in the region of Nouvelle-Aquitaine. Tulle is also the episcopal see of the Roman Catho ...

veil, and a wreath composed of orange blossoms, intermixed with flowers in compliment to the Scottish bridegroom: heather and myrtle.

Public reaction

There was intense public interest in the event, the second vice-regal wedding in the history of the colony. Its predecessor was the marriage of SirEdward Deas Thomson

Sir Edward Deas Thomson (1 June 1800 – 16 July 1879) was a Scotsman who became an administrator and politician in Australia, and was chancellor of the University of Sydney.

Background and early career

Thomson was born at Edinburgh, Scotland ...

, C.B., K.C.M.G.

The Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George is a British order of chivalry founded on 28 April 1818 by George IV, Prince of Wales, while he was acting as prince regent for his father, King George III.

It is named in honou ...

, with the daughter of Governor Sir Richard Bourke

General Sir Richard Bourke, KCB (4 May 1777 – 12 August 1855), was an Irish-born British Army officer who served as Governor of New South Wales from 1831 to 1837. As a lifelong Whig (Liberal), he encouraged the emancipation of convicts and ...

. The press reported that eight to ten thousand onlookers "...thronged King street from Macquarie Street to Elizabeth Street, and gave a large body of police great trouble to preserve order ... the crushing and screaming were almost continuous".

''King-street from Elizabeth-street to Macquarie-street, was thronged, and it became exceedingly difficult for the police, who were present in considerable force under Mr. sub-inspector Anderson, to preserve anything like order. Not only was the street thronged, but the balconies and the windows of the houses opposite the church were filled with sight-seers, the stone wall and railings enclosing the church were thick with people, and even the roof of the Supreme Court gave footing or a precarious support to adventurous individuals who were determined to see all that could be seen of the viceregal wedding. The crushing towards the church gates was enough to endanger life and limb. The persistent efforts made by the crowd to get within the railed enclosure caused the churchwardens to lock the gates, and to refuse, for some time, admittance to anybody, and even the guests specially invited to witness the marriage ceremony were subjected to much inconvenience and delay before they could reach the church doors. This, however, was almost unavoidable, for the crowd and the crushing were such that the severest measures were necessary to prevent the church being rushed by the people.''

Ancestry and family

Bride

Nora Robinson was born inSt Kitts

Saint Kitts, officially the Saint Christopher Island, is an island in the West Indies. The west side of the island borders the Caribbean Sea, and the eastern coast faces the Atlantic Ocean. Saint Kitts and the neighbouring island of Nevis cons ...

in the West Indies in 1858 during the period that her father was governor of the island (from 1855 to 1859).

The bride's father, Sir Hercules Robinson, was the governor of New South Wales. Her paternal grandfather was Admiral Hercules Robinson, R.N. The bride's uncle, William Robinson, was three times governor of Western Australia

The governor of Western Australia is the representative in Western Australia of the monarch of Australia, currently King Charles III. As with the other governors of the Australian states, the governor of Western Australia performs constitutional ...

and at the time of Nora's wedding, was governor of the Straits Settlements

The Straits Settlements were a group of British territories located in Southeast Asia. Headquartered in Singapore for more than a century, it was originally established in 1826 as part of the territories controlled by the British East India Comp ...

.

The bride's mother, Lady Robinson, née Nea Arthur Ada Rose D'Amour, was the fifth daughter of the ninth Viscount Valentia.

Groom

Alexander Kirkman Finlay was the second son of Alexander Struthers Finlay of Castle Toward, Argyllshire and Mrs Finlay in

Alexander Kirkman Finlay was the second son of Alexander Struthers Finlay of Castle Toward, Argyllshire and Mrs Finlay in Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popul ...

, Lanarkshire, born about 1845 and had a brother, Colin Campbell, his elder by one year. His father had represented Argyllshire

Argyll (; archaically Argyle, in modern Gaelic, ), sometimes called Argyllshire, is a historic county and registration county of western Scotland.

Argyll is of ancient origin, and corresponds to most of the part of the ancient kingdom of ...

in Parliament and his grandfather, Kirkman was also a parliamentarian as well as rector

Rector (Latin for the member of a vessel's crew who steers) may refer to:

Style or title

*Rector (ecclesiastical), a cleric who functions as an administrative leader in some Christian denominations

*Rector (academia), a senior official in an edu ...

of the University of Glasgow

, image = UofG Coat of Arms.png

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Coat of arms

Flag

, latin_name = Universitas Glasguensis

, motto = la, Via, Veritas, Vita

, ...

in 1817. The elder K. Finlay had acquired the large estate of Auchwhillan, and built Castle Toward on the shores of the Clyde near Dunoon

Dunoon (; gd, Dùn Omhain) is the main town on the Cowal peninsula in the south of Argyll and Bute, Scotland. It is located on the western shore of the upper Firth of Clyde, to the south of the Holy Loch and to the north of Innellan. As well ...

in 1820, to the plans of the architect David Hamilton. He was a pioneer in large-scale afforestation, a cotton trader, chairman of the chamber of commerce who formed the Glasgow East India Association to promote a national campaign for free trade. He was also chairman of the Clyde Navigation Trust and chairman of the Glasgow Gaelic Society and of the Glasgow Highland Society, which encouraged emigration. Alexander arrived in Australia about 1869 after finishing his education at Harrow School

(The Faithful Dispensation of the Gifts of God)

, established = (Royal Charter)

, closed =

, type = Public schoolIndependent schoolBoarding school

, religion = Church of E ...

and the University of Cambridge

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

.

Glenormiston

Finlay's property, ''Glenormiston'' nearNoorat

Noorat is a small township in southwestern Victoria, Australia. Noorat is located approximately 211 km west of Melbourne. The township is located at the base of Mount Noorat, a dormant volcano, which is considered to have Australia's larges ...

in Victoria, was funded by three wealthy Scots who sent out Highland farmer Niel Black in 1840 to set up its first station near Terang

Terang is a town in the Western District of Victoria, Australia. The town is in the Shire of Corangamite and on the Princes Highway south west of the state's capital, Melbourne. At the , Terang had a population of 1,824. At the 2001 census, ...

, western Victoria." Black was the son of a Scots farmer who sailed for Australia from Scotland in 1839. He was managing partner of Niel Black and Company, a subsidiary of Gladstone, Serjeantson and Company of Liverpool. The partnership had been formed between him and William Steuart of Glenormiston, Peebleshire, T.S. Gladstone of Gladstone, Serjeantson and Company, Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a popul ...

and the groom's father, A.S. Finlay of Toward Castle, Argyllshire. The company began with a financial backing of £6,000 which was soon increased to £10,000. "In 1840 Niel Black’s men were nearly all Highlanders brought out under the bounty immigration scheme." Melbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a met ...

and Adelaide

Adelaide ( ) is the capital city of South Australia, the state's largest city and the fifth-most populous city in Australia. "Adelaide" may refer to either Greater Adelaide (including the Adelaide Hills) or the Adelaide city centre. The dem ...

had been linked by telegraph for since December 1857 and graziers like Niel Black found the service "indispensable" for making arrangements about the herds. In 1867, the Duke of Edinburgh (the first member of the Royal family to visit Australia), had arrived in the district in late November after visiting Melbourne and sailing to Geelong in his ship the ''Galatea''. He was met by Niel Black and his two sons in full Highland

Highlands or uplands are areas of high elevation such as a mountainous region, elevated mountainous plateau or high hills. Generally speaking, upland (or uplands) refers to ranges of hills, typically from up to while highland (or highlands) is ...

regalia and they escorted him to Glenormiston where a kangaroo shoot had been organised. The Duke had his Highland piper

Piper may refer to:

People

* Piper (given name)

* Piper (surname)

Arts and entertainment Fictional characters Comics

* Piper (Morlock), in the Marvel Universe

* Piper (Mutate), in the Marvel Universe

Television

* Piper Chapman, lea ...

"pipe him into dinner".

Author Anthony Trollope

Anthony Trollope (; 24 April 1815 – 6 December 1882) was an English novelist and civil servant of the Victorian era. Among his best-known works is a series of novels collectively known as the '' Chronicles of Barsetshire'', which revolves ar ...

, who travelled extensively in Australia in the 1870s and wrote about each State, said that rich landowners of Victoria erect European country houses "with the addition of a wide verandah". Glenormiston was one of the homesteads where life at the time continued "not only pleasantly, but ... with grace." Trollope's observation was that at this time, life in the Western District must have been like "English country life in the eighteenth century" when the roads were bad, there was great plenty but not luxury, the men were fond of sport, the women stayed at home and looking after the house was done by the mistress and her daughters or the master and his sons rather than by domestics or servants as in England at the time. Trollope commented that "horses are cheap and servants are dear in Victoria."

Guests

Many dignitaries and colonial leaders - important members of Sydney society at the time - including administrators, officials, naval officers, lawyers and aristocrats, attended the ceremony. Among them were: "Hon. SirAlfred Stephen

Sir Alfred Stephen (20 August 180215 October 1894) was an Australian judge and Chief Justice of New South Wales.

Early life

Stephen was born at St Christopher in the West Indies. His father, John Stephen (1771–1833), was related to James S ...

, C.B., K C.M.G., M.L.C., Lieutenant Governor, and Lady Stephen; Commodore Hoskins, C.B., A.D.C., and several other naval officers; Colonel Roberts, N.S.W.A.; the Hon. Sir John Hay

John Milton Hay (October 8, 1838July 1, 1905) was an American statesman and official whose career in government stretched over almost half a century. Beginning as a private secretary and assistant to Abraham Lincoln, Hay's highest office was Un ...

, K,C.M.G., President of the Legislative Council, and Lady Hay; the Hon., Sir George Wigram Allen

Sir George Wigram Allen (16 May 1824 – 23 July 1885) was an Australian politician and philanthropist. He was Speaker in the New South Wales Legislative Assembly 1875–1883. Allen was held in high esteem. As speaker he showed dignity, courte ...

, Speaker of the Legislative Assembly, and Lady Allen; His Honor Sir William Manning and Lady Manning; the Hon. Professor Smith C.M.G., M.L.C., and Mrs. Smith; the Hon. R. Molyneaux; the Hon. Sir George Innes M.L.C., and Lady Innes; Mr. Edward Hill, and Mr. Edward Lee."

Gifts

The wedding presents, detailed in the press along with the names of their givers, were valuable and numerous. The bride's father gave her "a massivegold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au (from la, aurum) and atomic number 79. This makes it one of the higher atomic number elements that occur naturally. It is a bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile met ...

bracelet

A bracelet is an article of jewellery that is worn around the wrist. Bracelets may serve different uses, such as being worn as an ornament. When worn as ornaments, bracelets may have a wikt:supportive, supportive function to hold other items of ...

" and her mother "a large gold necklace

A necklace is an article of jewellery that is worn around the neck. Necklaces may have been one of the earliest types of adornment worn by humans. They often serve Ceremony, ceremonial, Religion, religious, magic (illusion), magical, or Funerary ...

and locket

A locket is a pendant that opens to reveal a space used for storing a photograph or other small item such as a lock of hair. Lockets are usually given to loved ones on holidays such as Valentine's Day and occasions such as christenings, wedding ...

". The best man (Captain Standish) gave solitaire large diamond

Diamond is a Allotropes of carbon, solid form of the element carbon with its atoms arranged in a crystal structure called diamond cubic. Another solid form of carbon known as graphite is the Chemical stability, chemically stable form of car ...

earring

An earring is a piece of jewelry attached to the ear via a piercing in the earlobe or another external part of the ear (except in the case of clip earrings, which clip onto the lobe). Earrings have been worn by people in different civilizations an ...

s. Other gifts of jewellery included a gold bracelet and pendant, set with amethyst

Amethyst is a violet variety of quartz. The name comes from the Koine Greek αμέθυστος ''amethystos'' from α- ''a-'', "not" and μεθύσκω (Ancient Greek) / μεθώ (Modern Greek), "intoxicate", a reference to the belief that t ...

, diamonds and pearl

A pearl is a hard, glistening object produced within the soft tissue (specifically the mantle) of a living shelled mollusk or another animal, such as fossil conulariids. Just like the shell of a mollusk, a pearl is composed of calcium carb ...

s (from the Hon. Sir George Wigram and Lady Allen); a gold locket

A locket is a pendant that opens to reveal a space used for storing a photograph or other small item such as a lock of hair. Lockets are usually given to loved ones on holidays such as Valentine's Day and occasions such as christenings, wedding ...

with diamond, centre of shamrock

A shamrock is a young sprig, used as a symbol of Ireland. Saint Patrick, Ireland's patron saint, is said to have used it as a metaphor for the Christian Holy Trinity. The name ''shamrock'' comes from Irish (), which is the diminutive of ...

s (from Mr. and Mrs. William Gilchrist); a sapphire

Sapphire is a precious gemstone, a variety of the mineral corundum, consisting of aluminium oxide () with trace amounts of elements such as iron, titanium, chromium, vanadium, or magnesium. The name sapphire is derived via the Latin "sapphir ...

and diamond ring (from Mrs. Salamon); a diamond bracelet (from the Hon. John Campbell); a gold bracelet set with diamond, sapphire, ruby

A ruby is a pinkish red to blood-red colored gemstone, a variety of the mineral corundum ( aluminium oxide). Ruby is one of the most popular traditional jewelry gems and is very durable. Other varieties of gem-quality corundum are called sa ...

, and emerald

Emerald is a gemstone and a variety of the mineral beryl (Be3Al2(SiO3)6) colored green by trace amounts of chromium or sometimes vanadium.Hurlbut, Cornelius S. Jr. and Kammerling, Robert C. (1991) ''Gemology'', John Wiley & Sons, New York, p ...

(from the Hon. Sir John Hay and Lady Hay).

The list reveals much about the relationship of the giver to the bridal couple, their social standing and what items were regarded as appropriate, beautiful or useful at the time. For example, the children of some guests, such as Master Robinson and Miss Allwood, gave gifts appropriate to their age. Master Robinson - Hercules Arthur Temple (1866-1933) - Nora's brother, gave a silver pencil case

A pencil case or pencil box is a container used to store pencils. A pencil case can also contain a variety of other stationery such as sharpeners, pens, glue sticks, erasers, scissors, rulers and calculators.

Pencil cases can be made from a v ...

. Miss Allwood's gift was a set of doilies

A doily (also doiley, doilie, doyly, doyley) is an ornamental mat, typically made of paper or fabric, and variously used for protecting surfaces or binding flowers, in food service presentation, or as a head covering or clothing ornamentatio ...

, painted from subjects in Alice's Adventures in Wonderland

''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' (commonly ''Alice in Wonderland'') is an 1865 English novel by Lewis Carroll. It details the story of a young girl named Alice (Alice's Adventures in Wonderland), Alice who falls through a rabbit hole into a ...

. The butler

A butler is a person who works in a house serving and is a domestic worker in a large household. In great houses, the household is sometimes divided into departments with the butler in charge of the dining room, wine cellar, and pantry. Some a ...

at the bride's home (Government House), gave "a handsome butter dish

A butter dish is defined as "a usually round or rectangular dish often with a drainer and a cover for holding butter at table". Before refrigerators existed, a covered dish made of crystal, silver, or china housed the butter. The first butter dish ...

".

Practical gifts included work-baskets, a travelling bag, a biscuit-box, a thimble

A thimble is a small pitted cup worn on the finger that protects it from being pricked or poked by a needle while sewing. The Old English word , the ancestor of thimble, is derived from Old English , the ancestor of the English word ''thumb''.

...

, an egg-boiler and a photograph-book. Some gifts give a glimpse of items necessary at the time but which are no longer needed or are now less valuable and more disposable. For example, "carved ivory" hair brushes have been replaced by plastic ones; visiting card

A visiting card, also known as a calling card, is a small card used for social purposes. Before the 18th century, visitors making social calls left handwritten notes at the home of friends who were not at home. By the 1760s, the upper classes in ...

s, inkstand

An inkstand is a stand or tray used to house writing instruments, with a tightly-capped inkwell and a sand shaker for rapid drying. A penwiper would often be included, and from the mid-nineteenth century, a compartment for steel nibs, which replace ...

s and riding whips are no longer in regular use.

Some of the gifts and references were consciously Australian. For example, the gift from the Marquis and the Marchioness of Normanby, (the Marquis was at the time governor of New Zealand

The governor-general of New Zealand ( mi, te kāwana tianara o Aotearoa) is the viceregal representative of the monarch of New Zealand, currently King Charles III. As the King is concurrently the monarch of 14 other Commonwealth realms and l ...

) of a writing set was made from silver and blackwood, probably the Australian timber ''Acacia melanoxylon

''Acacia melanoxylon'', commonly known as the Australian blackwood, is an ''Acacia'' species native in South eastern Australia. The species is also known as Blackwood, hickory, mudgerabah, Tasmanian blackwood, or blackwood acacia. The tree belon ...

''. The gift from Mrs Bladen Neill of a silk dresspiece was noted as "the product of Australian silkworms

The domestic silk moth (''Bombyx mori''), is an insect from the moth family Bombycidae. It is the closest relative of ''Bombyx mandarina'', the wild silk moth. The silkworm is the larva or caterpillar of a silk moth. It is an economically imp ...

".

Subsequent events

The groom returned to Castle Toward, his family home in Scotland, where he died on 29 July 1883 from "phthisis" (now known as

The groom returned to Castle Toward, his family home in Scotland, where he died on 29 July 1883 from "phthisis" (now known as tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in ...

), five years after his marriage."1883 Register of deaths in the Parish of Dunoon, County of Argyle, p.25 He would have been about 38 years old. His will, showing a personal estate of £493 14s. 9d. was proved by his older brother, Colin Campbell Finlay, who was present at Alexander's death and one of his Executor

An executor is someone who is responsible for executing, or following through on, an assigned task or duty. The feminine form, executrix, may sometimes be used.

Overview

An executor is a legal term referring to a person named by the maker of a ...

s.

Four years later, on 8 September 1887, Nora Finlay married Charles Richard Durant (born about 1854) of the Parish of St James, Piccadilly

Piccadilly () is a road in the City of Westminster, London, to the south of Mayfair, between Hyde Park Corner in the west and Piccadilly Circus in the east. It is part of the A4 road that connects central London to Hammersmith, Earl's Court, ...

, at the Parish Church of Eaton Square

Eaton Square is a rectangular, residential garden square in London's Belgravia district. It is the largest square in London. It is one of the three squares built by the landowning Grosvenor family when they developed the main part of Belgravia ...

, London. Her son, Noel Fairfax Durant was born in 1889, while their recorded address was 13 Egerton Gardens

Egerton Gardens is a street and communal garden, regionally termed a garden square, in South Kensington, London SW3.

Location

The street runs roughly south-west to north-east, off Brompton Road. Egerton Crescent, runs roughly off it, and Ege ...

, London. She died in London on 31 December 1938, leaving an estate of £124,344 7s. 2d. At the time she was a widow living at 22 Emperors-gate, Kensington

Kensington is a district in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea in the West End of London, West of Central London.

The district's commercial heart is Kensington High Street, running on an east–west axis. The north-east is taken up b ...

.

References

;Notes ;Bibliography * * *{{cite book , last = Trollope , first = Anthony, title = Australia and New Zealand. Division III, Victoria , publisher = George Robertson , location = Sydney , year = 1873 Marriage, unions and partnerships in Australia Events in Sydney 1878 in Australia 1870s in Sydney August 1878 events