/ref> However, the Jewish population remained strong in Galilee, Golan, Bet Shean Valley, and the eastern, southern, and western edges of Judea.David Goodblatt, 'The political and social history of the Jewish community in the Land of Israel,' in William David Davies, Louis Finkelstein, Steven T. Katz (eds.

''The Cambridge History of Judaism: Volume 4, The Late Roman-Rabbinic Period''

Cambridge University Press, 2006 pp.404-430, p.406. Roman casualties were also considered heavy – XXII ''Deiotariana'' was disbanded, perhaps after serious losses in this conflict.L. J. F. Keppie (2000) ''Legions and veterans: Roman army papers 1971-2000'' Franz Steiner Verlag, pp 228–229 In a possibly punitive act, the province of Judaea was renamed Syria Palaestina.H.H. Ben-Sasson, ''A History of the Jewish People'', Harvard University Press, 1976, , page 334: "In an effort to wipe out all memory of the bond between the Jews and the land, Hadrian changed the name of the province from Judaea to Syria-Palestina, a name that became common in non-Jewish literature."Ariel Lewin. ''The archaeology of Ancient Judea and Palestine''. Getty Publications, 2005 p. 33. "It seems clear that by choosing a seemingly neutral name - one juxtaposing that of a neighboring province with the revived name of an ancient geographical entity (Palestine), already known from the writings of Herodotus - Hadrian was intending to suppress any connection between the Jewish people and that land." ''The Bar Kokhba War Reconsidered''

by Peter Schäfer, The Bar Kokhba revolt greatly influenced the course of Jewish history and the philosophy of the Jewish religion. Despite easing the persecution of Jews following Hadrian's death in 138 CE, the Romans barred Jews from Jerusalem, except for attendance in

Background

After the''Ancient Rome a Military and Political History''

Cambridge University Press 2007 p.230 The claim is often considered suspect.

Timeline of events

First phase

Eruption of the revolt

Jewish leaders carefully planned the second revolt to avoid the numerous mistakes that had plagued the firstStalemate and reinforcements

Given the continuing inability of Legio X and Legio VI to subdue the rebels, additional reinforcements were dispatched from neighbouring provinces. Gaius Quinctius Certus Poblicius Marcellus, Gaius Poblicius Marcellus, the Legate of Roman Syria, arrived commanding Legio III Gallica, while Titus Haterius Nepos (consul), Titus Haterius Nepos, the governor of Roman Arabia, brought Legio III Cyrenaica. Later on it is proposed by some historians that Legio XXII Deiotariana was sent from Arabia Petraea, but was Demise of Legio XXII Deiotariana, ambushed and massacred on its way to Aelia Capitolina (Jerusalem), and possibly disbanded as a result. Legio II Traiana Fortis, previously stationed in Egypt, may have also arrived in Judea in this stage. By that time the number of Roman troops in Judea stood at nearly 80,000—a number still inferior to rebel forces, who were also more familiar with the terrain and occupied strong fortifications. Many Jews from the diaspora made their way to Judea to join Bar Kokhba's forces from the beginning of the rebellion, with the Talmud recorded tradition that hard tests were imposed on recruits due to the inflated number of volunteers. Some documents seem to indicate that many of those who enlisted in Bar Kokhba's forces could only speak Greek, and it is unclear whether these were Jews or non-Jews. According to Rabbinic sources some 400,000 men were at the disposal of Bar Kokhba at the peak of the rebellion.Second phase

From guerilla warfare to open engagement

The outbreak and initial success of the rebellion took the Romans by surprise. The rebels incorporated combined tactics to fight the Roman Army. According to some historians, Bar Kokhba's army mostly practiced guerrilla warfare, inflicting heavy casualties. This view is largely supported by Cassius Dio, who wrote that the revolt began with covert attacks in line with preparation of hideout systems, though after taking over the fortresses Bar Kokhba turned to direct engagement due to his superiority in numbers.Rebel Judean statehood

Simon Bar Kokhba took the title ''Nasi (Hebrew title), Nasi Israel'' and ruled over an entity named ''Israel'' that was virtually independent for over two and a half years. The Jewish sage Rabbi Akiva, who was the spiritual leader of the revolt, identified Simon Bar Kosiba as the Jewish messiah, and gave him the surname "Bar Kokhba" meaning "Son of a Star" in the Aramaic language, from the Star Prophecy verse from Book of Numbers, Numbers : "There shall come a star out of Jacob". The name Bar Kokhba (disambiguation), Bar Kokhba does not appear in the Talmud but in ecclesiastical sources. The era of the Salvation#Judaism, redemption of Israel was announced, contracts were signed and a large quantity of Bar Kochba Revolt coinage, Bar Kokhba Revolt coinage was struck over foreign coins.

Simon Bar Kokhba took the title ''Nasi (Hebrew title), Nasi Israel'' and ruled over an entity named ''Israel'' that was virtually independent for over two and a half years. The Jewish sage Rabbi Akiva, who was the spiritual leader of the revolt, identified Simon Bar Kosiba as the Jewish messiah, and gave him the surname "Bar Kokhba" meaning "Son of a Star" in the Aramaic language, from the Star Prophecy verse from Book of Numbers, Numbers : "There shall come a star out of Jacob". The name Bar Kokhba (disambiguation), Bar Kokhba does not appear in the Talmud but in ecclesiastical sources. The era of the Salvation#Judaism, redemption of Israel was announced, contracts were signed and a large quantity of Bar Kochba Revolt coinage, Bar Kokhba Revolt coinage was struck over foreign coins.

From open warfare to rebel defensive tactics

With the slowly advancing Roman army cutting supply lines, the rebels engaged in long-term defense. The defense system of Judean towns and villages was based mainly on hideout caves, which were created in large numbers in almost every population center. Many houses utilized underground hideouts, where Judean rebels hoped to withstand Roman superiority by the narrowness of the passages and even ambushes from underground. The cave systems were often interconnected and used not only as hideouts for the rebels but also for storage and refuge for their families. Hideout systems were employed in the Judean hills, the Judean desert, northern Negev, and to some degree also in Galilee, Samaria and Jordan Valley. As of July 2015, some 350 hideout systems have been mapped within the ruins of 140 Jewish villages.Third phase

Julius Severus' campaign

Following a series of setbacks, Hadrian called his generalBattle of Tel Shalem (theory)

According to some views one of the crucial battles of the war took place near Tel Shalem in the Beit She'an valley, near what is now identified as the legionary camp of Legio VI Ferrata. This theory was proposed by Werner Eck in 1999, as part of his general maximalist work which did put the Bar Kokhba revolt as a very prominent event on the course of the Roman Empire's history. Next to the camp, archaeologists unearthed the remnants of a triumphal arch, which featured a dedication to Emperor Hadrian, which most likely refers to the defeat of Bar Kokhba's army. Additional finds at Tel Shalem, including a bust of Emperor Hadrian, specifically link the site to the period. The theory for a major decisive battle in Tel Shalem implies a significant extension of the area of the rebellion, with Werner Eck suggesting the war encompassed also northern Valleys together with Galilee.Judean highlands and desert

Simon bar Kokhba declared Herodium as his secondary headquarters. Its commander was Yeshua ben Galgula, likely Bar Kokhba's second or third line of command. Archaeological evidence for the revolt was found all over the site, from the outside buildings to the water system under the mountain. Inside the water system, supporting walls built by the rebels were discovered, and another system of caves was found. Inside one of the caves, burned wood was found which was dated to the time of the revolt. The fortress was besieged by the Romans in late 134 and was taken by the end of the year or early in 135.

Simon bar Kokhba declared Herodium as his secondary headquarters. Its commander was Yeshua ben Galgula, likely Bar Kokhba's second or third line of command. Archaeological evidence for the revolt was found all over the site, from the outside buildings to the water system under the mountain. Inside the water system, supporting walls built by the rebels were discovered, and another system of caves was found. Inside one of the caves, burned wood was found which was dated to the time of the revolt. The fortress was besieged by the Romans in late 134 and was taken by the end of the year or early in 135.

Fourth phase

The last phase of the revolt is characterized by Bar Kokhba's loss of territorial control, with the exception of the surroundings of the Betar fortress, where he made his last stand against the Romans. The Roman Army had meanwhile turned to eradicate smaller fortresses and hideout systems of captured villages, turning the conquest into a Battle of annihilation, campaign of annihilation.Siege of Betar

After losing many of their strongholds, Bar Kokhba and the remnants of his army withdrew to the fortress of Betar (fortress), Betar, which subsequently came under siege in the summer of 135. Legio V Macedonica and Legio XI Claudia are said to have taken part in the siege. According to Jewish tradition, the fortress was breached and destroyed on the fast of Tisha B'av, the ninth day of the lunar month Av, a day of mourning for the destruction of the First and the Second Jewish Temple. Rabbinical literature ascribes the defeat to Bar Kokhba killing his maternal uncle, Rabbi Eleazar of Modi'im, Elazar Hamudaʻi, after suspecting him of collaborating with the enemy, thereby forfeiting Divine protection. The horrendous scene after the city's capture could be best described as a massacre. The Jerusalem Talmud relates that the number of dead in Betar was enormous, that the Romans "went on killing until their horses were submerged in blood to their nostrils."

After losing many of their strongholds, Bar Kokhba and the remnants of his army withdrew to the fortress of Betar (fortress), Betar, which subsequently came under siege in the summer of 135. Legio V Macedonica and Legio XI Claudia are said to have taken part in the siege. According to Jewish tradition, the fortress was breached and destroyed on the fast of Tisha B'av, the ninth day of the lunar month Av, a day of mourning for the destruction of the First and the Second Jewish Temple. Rabbinical literature ascribes the defeat to Bar Kokhba killing his maternal uncle, Rabbi Eleazar of Modi'im, Elazar Hamudaʻi, after suspecting him of collaborating with the enemy, thereby forfeiting Divine protection. The horrendous scene after the city's capture could be best described as a massacre. The Jerusalem Talmud relates that the number of dead in Betar was enormous, that the Romans "went on killing until their horses were submerged in blood to their nostrils."

Final accords

According to a rabbinic midrash, the Romans executed eight leading members of the Sanhedrin (The list of Ten Martyrs include two earlier rabbis): Rabbi Akiva; Rabbi Hanania ben Teradion; the interpreter of the Sanhedrin, Rabbi Huspith; Rabbi Eliezer ben Shamua; Rabbi Hanina ben Hakinai; Rabbi Jeshbab the Scribe; Rabbi Yehuda ben Dama; and Rabbi Yehuda ben Baba. The precise date of Akiva's execution is disputed, some suggesting to date it to the beginning of the revolt based on the midrash, while others link it to final phases. The rabbinic account describes agonizing tortures: Akiva was Flaying, flayed with iron combs, Rabbi Ishmael had the skin of his head pulled off slowly, and Rabbi Hanania was burned at a stake, with wet wool held by a Torah scroll wrapped around his body to prolong his death. Bar Kokhba's fate is not certain, with two alternative traditions in the Babylonian Talmud ascribing the death of Bar Kokhba either to a snakebite or other natural causes during the Roman siege or possibly killed on the orders of the Sanhedrin, as a List of Jewish messiah claimants, false messiah. According to Lamentations Rabbah, the head of Bar Kokhba was presented to Emperor Hadrian after the Siege of Betar. Following the Fall of Betar, the Roman forces went on a rampage of systematic killing, eliminating all remaining Jewish villages in the region and seeking out the refugees. Legio III Cyrenaica was the main force to execute this last phase of the campaign. Historians disagree on the duration of the Roman campaign following the fall of Betar. While some claim further resistance was broken quickly, others argue that pockets of Jewish rebels continued to hide with their families into the winter months of late 135 and possibly even spring 136. By early 136 however, it is clear that the revolt was defeated.Aftermath

Jewish casualties and the destruction of Judean countryside

Modern historians view the Bar Kokhba Revolt as having decisive historic importance. They note that, unlike in the aftermath of the''The Targum of Judges,''

BRILL 1995 p.434. The Sages endeavoured to halt Jewish Jewish diaspora, dispersal, and even banned emigration from Palestine, branding those who settled outside its borders as idolaters.

Roman losses

Cassius Dio wrote that "Many Romans, moreover, perished in this war. Therefore, Hadrian, in writing to the Senate, did not employ the opening phrase commonly affected by the emperors: 'If you and your children are in health, it is well; I and the army are in health.'"Cassius Dio, ''Roman History'' Some argue that the exceptional number of preserved Roman veteran diplomas from the late 150s and 160 CE indicate an unprecedented conscription across the Roman Empire to replenish heavy losses within military legions and auxiliary units between 133 and 135, corresponding to the revolt. As noted above, XXII ''Deiotariana'' may have been disbanded after serious losses.livius.org account(Legio XXII Deiotariana) In addition, some historians argue that Legio IX Hispana's disbandment in the mid-2nd century could have been a result of this war. Previously it had generally been accepted that the Ninth disappeared around 108 CE, possibly suffering its demise in Britain, according to Theodor Mommsen, Mommsen; but archaeological findings in 2015 from Nijmegen, dated to 121 CE, contained the known inscriptions of two senior officers who were deputy commanders of the Ninth in 120 CE, and lived on for several decades to lead distinguished public careers. It was concluded that the Legion was disbanded between 120 and 197 CE—either as a result of fighting the Bar Kokhba revolt, or in Cappadocia (Roman province), Cappadocia (161), or at the Danube (162). Legio X Fretensis sustained heavy casualties during the revolt.

Other casualties

The revolt was led by the Judean Pharisees, with other Jewish and non-Jewish factions also playing a role. Jewish communities of Galilee who sent militants to the revolt in Judea were largely spared total destruction, though they did suffer persecutions and massive executions. Samaria partially supported the revolt, with evidence accumulating that notable numbers of Samaritans, Samaritan youths participated in Bar Kokhba's campaigns; though Roman wrath was directed at Samaritans, their cities were also largely spared from the total destruction unleashed on Judea. Eusebius of Caesarea wrote thatPunitive measures against Jews

After the suppression of the revolt, Hadrian promulgated a series of religious edicts aimed at uprooting the Jewish nationalism in Judea. He prohibited Torah law and the Hebrew calendar, and executed Judaic scholars. The sacred scrolls of Judaism were ceremonially burned at the large Temple complex for Jupiter which he built on theLater relations between the Jews and the Roman Empire

Relations between the Jews in the region and the Roman Empire continued to be complicated. Constantine the Great and Judaism, Constantine I allowed Jews to mourn their defeat and humiliation once a year on"Julian and the Jews 361–363 CE"

(Fordham University, The Jesuit University of New York) an

Julian's support of Judaism caused Jews to call him "Julian the Hellenes (religion), Hellene". Julian's fatal wound in the Persian campaign put an end to Jewish aspirations, and Julian's successors embraced Christianity through the entirety of Byzantine Empire, Byzantine rule of Jerusalem, preventing any Jewish claims. In 438 CE, when the Empress Licinia Eudoxia, Eudocia removed the ban on Jews' praying at the Temple Mount, Temple site, the heads of the Community in Galilee issued a call "to the great and mighty people of the Jews" which began: "Know that the end of the exile of our people has come!" However the Christian population of the city saw this as a threat to their primacy, and a riot erupted which chased Jews from the city. During the 5th and the 6th centuries, a series of Samaritan revolts broke out across the Palaestina Prima province. Especially violent were the third and the fourth revolts, which resulted in near annihilation of the Samaritan community. It is likely that the Samaritan revolts#556 Samaritan revolt, Samaritan revolt of 556 was joined by the Jewish community, which had also suffered brutal suppression of their religion under Emperor Justinian. In the belief of restoration to come, in the early 7th century the Jews made an Jewish revolt against Heraclius, alliance with the Sassanid Empire, Persians, joining the Persian invasion of Palaestina Prima in 614 to overwhelm the Byzantine Empire, Byzantine garrison, and gaining autonomous rule over Jerusalem. However, their autonomy was brief: the Nehemiah ben Hushiel, Jewish leader was shortly assassinated during a Christian revolt and, though Jerusalem was reconquered by Persians and Jews within 3 weeks, it fell into anarchy. With the subsequent withdrawal of Persian forces, Jews surrendered to the Byzantines in 625 CE or 628 CE. Byzantine control of the region was finally lost to Muslim Arab armies in 637 CE, when Umar ibn al-Khattab completed the conquest of Akko.

Legacy

In Rabbinic Judaism

The disastrous end of the revolt occasioned major changes in Jewish religious thought.In Zionism and modern Israel

In the post-rabbinical era, the Bar Kokhba Revolt became a symbol of valiant national resistance. The Zionist youth movement Betar took its name from Bar Kokhba's traditional last stronghold, and David Ben-Gurion, Israel's first prime minister, took his Hebrew last name from one of Bar Kokhba's generals. A popular children's song, included in the curriculum of Israeli kindergartens, has the refrain "Bar Kokhba was a Hero/He fought for Liberty," and its words describe Bar Kokhba as being captured and thrown into a lion's den, but managing to escape riding on the lion's back.The military and militarism in Israeli society

' by Edna Lomsky-Feder, Eyal Ben-Ari]." Retrieved on September 3, 2010

Geographic extent of the revolt

Over the years, two schools formed in the analysis of the Revolt. One of them is ''maximalists'', who claim that the revolt spread through the entire Judea Province and beyond it into neighboring provinces. The second one is that of the ''minimalists'', who restrict the revolt to the area of the Judaean hills and immediate environs.M. Menahem. ''WHAT DOES TEL SHALEM HAVE TO DO WITH THE BAR KOKHBA REVOLT?''. U-ty of Haifa / U-ty of Denver. SCRIPTA JUDAICA CRACOVIENSIA. Vol. 11 (2013) pp. 79–96.Judea proper

It is generally accepted that the Bar Kokhba revolt encompassed all of Judea, namely the villages of the Judean hills, the Judean desert, and northern parts of the Negev desert. It is not known whether the revolt spread outside of Judea.Jerusalem

Until 1951, Bar Kokhba Revolt coinage was the sole archaeological evidence for dating the revolt. These coins include references to "Year One of the redemption of Israel", "Year Two of the freedom of Israel", and "For the freedom of Jerusalem". Despite the reference to Jerusalem, as of early 2000s, archaeological finds, and the lack of revolt coinage found in Jerusalem, supported the view that the revolt did not capture Jerusalem.: "Returning to the Bar Kokhba revolt, we should note that up until the discovery of the first Bar Kokhba documents in Wadi Murabba'at in 1951, Bar Kokhba coins were the sole archaeological evidence available for dating the revolt. Based on coins overstock by the Bar Kokhba administration, scholars dated the beginning of the Bar Kokhba regime to the conquest of Jerusalem by the rebels. The coins in question bear the following inscriptions: "Year One of the redemption of Israel", "Year Two of the freedom of Israel", and "For the freedom of Jerusalem". Up until 1948 some scholars argued that the "Freedom of Jerusalem" coins predated the others, based upon their assumption that the dating of the Bar Kokhba regime began with the rebel capture Jerusalem." L. Mildenberg's study of the dies of the Bar Kokhba definitely established that the "Freedom of Jerusalem" coins were struck later than the ones inscribed "Year Two of the freedom of Israel". He dated them to the third year of the revolt.' Thus, the view that the dating of the Bar Kokhba regime began with the conquest of Jerusalem is untenable. lndeed, archeological finds from the past quarter-century, and the absence of Bar Kokhba coins in Jerusalem in particular, support the view that the rebels failed to take Jerusalem at all." In 2020, the fourth Bar Kokhba minted coin and the first inscribed with the word "Jerusalem" was found in Jerusalem Old City excavations. Despite this discovery, the Israel Antiques Authority still maintained the opinion that Jerusalem was not taken by the rebels, due to the fact that of thousands of Bar Kokhba coins had been found outside Jerusalem, but only four within the city (out of more than 22,000 found within the city). The Israel Antiques Authority's archaeologists Moran Hagbi and Dr. Joe Uziel speculated that "It is possible that a Roman soldier from the Tenth Legion found the coin during one of the battles across the country and brought it to their camp in Jerusalem as a souvenir."Galilee

Among those findings are the rebel hideout systems in the Galilee, which greatly resemble the Bar Kokhba hideouts in Judea, and though are less numerous, are nevertheless important. The fact that Galilee retained its Jewish character after the end of the revolt has been taken as an indication by some that either the revolt was never joined by Galilee or that the rebellion was crushed relatively early there compared to Judea.Northern valleys

Several historians, notably W. Eck of the U-ty of Cologne, theorized that the Tel Shalem arch depicted a major battle between Roman armies and Bar Kokhba's rebels in Bet Shean valley, thus extending the battle areas some 50 km northwards from Judea. The 2013 discovery of the Legio, military camp of Legio VI Ferrata near Tel Megiddo, and ongoing excavations there may shed light to extension of the rebellion to the northern valleys. However, Eck's theory on battle in Tel Shalem is rejected by M. Mor, who considers the location implausible given Galilee's minimal (if any) participation in the Revolt and distance from the main conflict flareup in Judea proper.Samaria

A 2015 archaeological survey in Samaria identified some 40 hideout cave systems from the period, some containing Bar Kokhba's minted coins, suggesting that the war raged in Samaria at high intensity. he, התגלית שהוכיחה: מרד בר כוכבא חל גם בשומרון}NRG. 15 July 2015.

Transjordan

Bowersock suggested of linking the Nabataeans, Nabateans to the revolt, claiming "a greater spread of hostilities than had formerly been thought... the extension of the Jewish revolt into northern Transjordan (region), Transjordan and an additional reason to consider the spread of local support among Safaitic tribes and even at Jerash, Gerasa."Sources

The revolt is mostly still shrouded in mystery, and only one brief historical account of the rebellion survives.Hanan Eshe'The Bar Kochba revolt, 132-135,'

in William David Davies, Louis Finkelstein, Steven T. Katz (eds.) ''The Cambridge History of Judaism: Volume 4, The Late Roman-Rabbinic Period,'' pp.105-127, p.105.

Dio Cassius

The best recognized source for the revolt isEusebius of Caesarea

The Christian author Eusebius of Caesarea wrote a brief account of the revolt within the Church History (Eusebius) compilation, notably mentioning Bar Chochebas (which means “star” according to Eusebius) as the leader of the Jewish rebels and their last stand at Beththera (i.e. Betar (fortress), Betar). Though Eusebius lived one and a half centuries after the revolt and wrote the brief account from the Christian theological perspective, his account provides important details on the revolt and its aftermath in Judea. Eusebius does also describe what had remained of Jewish population of Judea at his time—naming seven Jewish communities in Roman Palaestina (former Judaea).Jerusalem Talmud

The Jerusalem Talmud contains descriptions of the results of the rebellion, including the Roman executions of Judean leaders and religious persecution. The material however is lacking context and detail, though does contain reference to the Roman Governor Rufus (as Tinusrufus) and names the Jewish leader as Ben Kuziba.Primary sources

The discovery of the Cave of Letters in the Dead Sea area, dubbed as "Bar Kokhba archive", which contained letters actually written by Bar Kokhba and his followers, has added much new primary source data, indicating among other things that either a pronounced part of the Jewish population spoke only Greek or there was a foreign contingent among Bar Kokhba's forces, accounted for by the fact that his military correspondence was, in part, conducted in Greek. Close to the Cave of Letters is the Cave of Horror, where the remains of Jewish refugees from the rebellion were discovered along with fragments of letters and writings. Several more brief sources have been uncovered in the area over the past century, including references to the revolt from Nabatea and Roman Syria. Roman inscriptions in Tel Shalem, Betar fortress, Jerusalem and other locations also contribute to the current historical understanding of the Bar Kokhba War.Archaeology

Destroyed Jewish villages and fortresses

Several archaeological surveys have been performed during the 20th and 21st centuries in ruins of Jewish villages across Judea and Samaria, as well in the Roman-dominated cities on the Israeli coastal plain.

Several archaeological surveys have been performed during the 20th and 21st centuries in ruins of Jewish villages across Judea and Samaria, as well in the Roman-dominated cities on the Israeli coastal plain.

Herodium fortress

Herodium was excavated by archaeologist Ehud Netzer in the 1980s, publishing results in 1985. According to findings, during the later Bar-Kokhba revolt, complex tunnels were dug, connecting the earlier cisterns with one another. These led from the Herodium fortress to hidden openings, which allowed surprise attacks on Roman units besieging the hill. As opposed to the narrow and restricted tunnel complexes from the Judean plain, the Herodium tunnels were broad, with high ceilings, allowing for rapid movement of armed soldiers.

Herodium was excavated by archaeologist Ehud Netzer in the 1980s, publishing results in 1985. According to findings, during the later Bar-Kokhba revolt, complex tunnels were dug, connecting the earlier cisterns with one another. These led from the Herodium fortress to hidden openings, which allowed surprise attacks on Roman units besieging the hill. As opposed to the narrow and restricted tunnel complexes from the Judean plain, the Herodium tunnels were broad, with high ceilings, allowing for rapid movement of armed soldiers.

Betar fortress

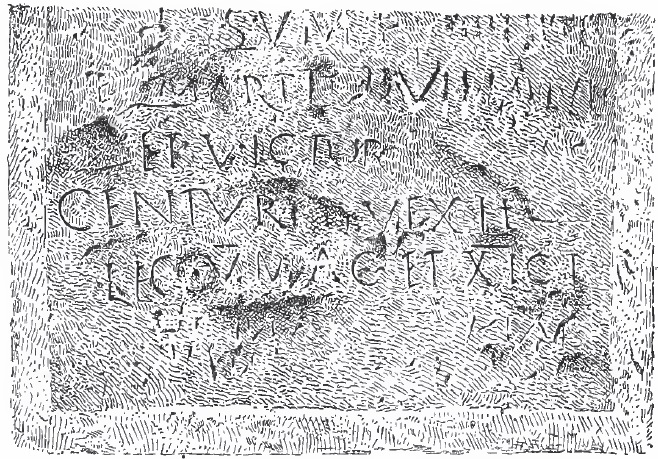

The ruins of Betar, the last fortress of Bar Kokhba, destroyed by Hadrian's legions in 135 CE, is located in the vicinity of the towns of Battir and Beitar Illit. A stone inscription bearing Latin characters and discovered near Betar shows that the Legio V Macedonica, Fifth Macedonian Legion and the Legio XI Claudia, Eleventh Claudian Legion took part in the siege.C. Clermont-Ganneau, ''Archaeological Researches in Palestine during the Years 1873-74'', London 1899, pp. 263-270.Hideout systems

Cave of Letters

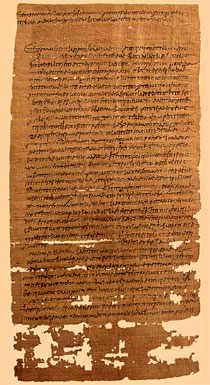

The Cave of Letters was surveyed in explorations conducted in 1960–1961, when letters and fragments of papyri were found dating back to the period of the Bar Kokhba revolt. Some of these were personal letters between Bar Kokhba and his subordinates, and one notable bundle of papyri, known as the Babata or Babatha cache, revealed the life and trials of a woman, Babata, who lived during this period.

The Cave of Letters was surveyed in explorations conducted in 1960–1961, when letters and fragments of papyri were found dating back to the period of the Bar Kokhba revolt. Some of these were personal letters between Bar Kokhba and his subordinates, and one notable bundle of papyri, known as the Babata or Babatha cache, revealed the life and trials of a woman, Babata, who lived during this period.

Cave of Horror

Cave of Horror is the name given to Cave 8 in the Judaean Desert of Israel, where the remains of Jewish refugees from the Bar Kokhba revolt were found. The nickname "Cave of Horror" was given after the skeletons of 40 men, women and children were discovered. Three potsherds with the names of three of the deceased were also found alongside the skeletons in the cave.Roman legionary camps

A number of locations have been identified with Roman Legionary camps in the time of the Bar Kokhba War, including in Tel Shalem, Jerusalem, Lajjun and more.Jerusalem inscription dedicated to Hadrian (129/30 CE)

In 2014, one half of a Latin inscription was discovered in Jerusalem during excavations near the Damascus Gate.Jerusalem Post. 21 October 201WATCH: 2,000-YEAR-OLD INSCRIPTION DEDICATED TO ROMAN EMPEROR UNVEILED IN JERUSALEM

/ref> It was identified as the right half of a complete inscription, the other part of which was discovered nearby in the late 19th century and is currently on display in the courtyard of Jerusalem's Studium Biblicum Franciscanum Museum. The complete inscription was translated as follows: :: To the Imperator Caesar Traianus Hadrianus Augustus, son of the deified Traianus Parthicus, grandson of the deified Nerva, high priest, invested with tribunician power for the 14th time, consul for the third time, father of the country (dedicated by) the 10th legion Fretensis Antoniniana. The inscription was dedicated by Legio X Fretensis to the emperor Hadrian in the year 129/130 CE. The inscription is considered to greatly strengthen the claim that indeed the emperor visited Jerusalem that year, supporting the traditional claim that Hadrian's visit was among the main causes of the Bar Kokhba Revolt, and not the other way around.

Tel Shalem triumphal arc and Hadrian's statue

The location was identified as a Roman military post during the 20th century, with archaeological excavation performed in the late 20th century following an accidental discovery of Hadrian's bronze statue in the vicinity of the site in 1975. Remains of a large Roman military camp and fragments of a triumphal arc dedicated to Emperor Hadrian were consequently discovered at the site.See also

* List of conflicts in the Near East * Sicaricon (Jewish law)References

Bibliography

* * * * * Yohannan Aharoni & Michael Avi-Yonah, ''The MacMillan Bible Atlas'', Revised Edition, pp. 164–65 (1968 & 1977 by Carta Ltd.) * ''The Documents from the Bar Kokhba Period in the Cave of Letters (Judean Desert studies)''. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1963–2002. ** Vol. 2, "Greek Papyri", edited by Naphtali Lewis; "Aramaic and Nabatean Signatures and Subscriptions", edited by Yigael Yadin and Jonas C. Greenfield. (). ** Vol. 3, "Hebrew, Aramaic and Nabatean–Aramaic Papyri", edited Yigael Yadin, Jonas C. Greenfield, Ada Yardeni, BaruchA. Levine (). * W. Eck, 'The Bar Kokhba Revolt: the Roman point of view' in the ''Journal of Roman Studies'' 89 (1999) 76ff. * Peter Schäfer (editor), ''Bar Kokhba reconsidered'', Tübingen: Mohr: 2003 * Aharon Oppenheimer, 'The Ban of Circumcision as a Cause of the Revolt: A Reconsideration', in ''Bar Kokhba reconsidered'', Peter Schäfer (editor), Tübingen: Mohr: 2003 * Faulkner, Neil. ''Apocalypse: The Great Jewish Revolt Against Rome''. Stroud, Gloucestershire, UK: Tempus Publishing, 2004 (hardcover, ). * Goodman, Martin. ''The Ruling Class of Judaea: The Origins of the Jewish Revolt against Rome, A.D. 66–70''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987 (hardcover, ); 1993 (paperback, ). * Richard Marks: ''The Image of Bar Kokhba in Traditional Jewish Literature: False Messiah and National Hero'': University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press: 1994: * * David Ussishkin: "Archaeological Soundings at Betar, Bar-Kochba's Last Stronghold", in: ''Tel Aviv. Journal of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University'' 20 (1993) 66ff. * Yadin, Yigael. ''Bar-Kokhba: The Rediscovery of the Legendary Hero of the Second Jewish Revolt Against Rome''. New York: Random House, 1971 (hardcover, ); London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1971 (hardcover, ). * Mildenberg, Leo. ''The Coinage of the Bar Kokhba War''. Switzerland: Schweizerische Numismatische Gesellschaft, Zurich, 1984 (hardcover, ).External links

Wars between the Jews and Romans: Simon ben Kosiba (130-136 CE)

with English translations of sources.

Archaeologists find tunnels from Jewish revolt against Romans

by the Associated Press. ''Haaretz'' March 13, 2006

Bar Kokba and Bar Kokba War

''Jewish Encyclopedia''

Sam Aronow - The Bar Kochba Revolt , 132 - 136

{{Authority control Bar Kokhba revolt, 132 133 134 135 136 130s in the Roman Empire 130s conflicts 2nd-century rebellions Genocide of indigenous peoples Jewish nationalism Jewish rebellions Jewish refugees Jews and Judaism in the Roman Empire Judea (Roman province) Religion-based wars Genocides in Asia