Władysław Reymont on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

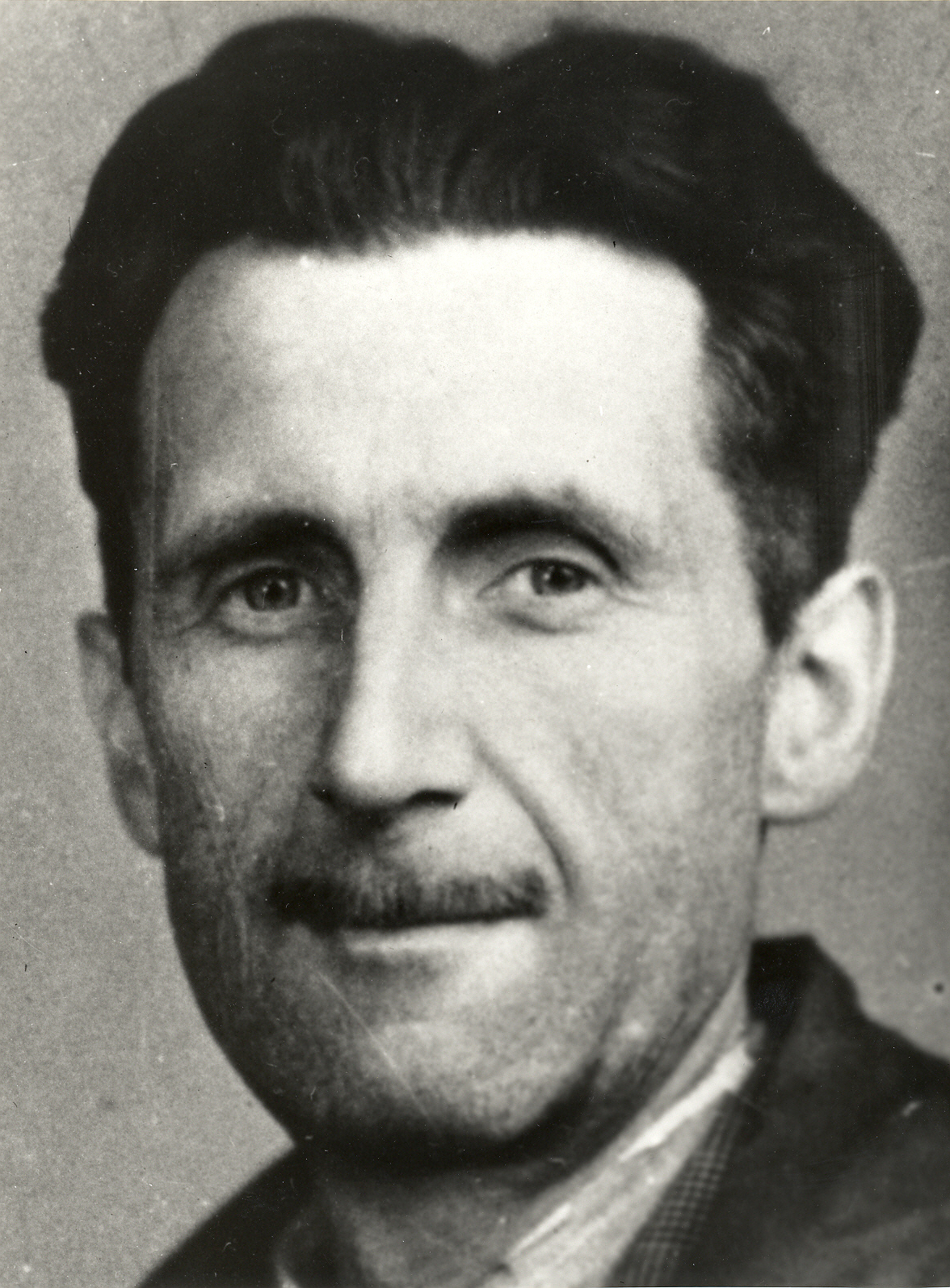

Władysław Stanisław Reymont (, born Rejment; 7 May 1867 – 5 December 1925) was a Polish novelist and the 1924 laureate of the Nobel Prize in Literature. His best-known work is the award-winning four-volume novel '' Chłopi'' (''The Peasants'').

Born into an impoverished

When his ''Korespondencje'' (''Correspondence'') from Rogów,

When his ''Korespondencje'' (''Correspondence'') from Rogów,

In November 1924 he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature over rivals

In November 1924 he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature over rivals

Critics admit a number of similarities between Reymont and the Naturalists. They stress that this was not a "borrowed" Naturalism but rather a record of life as experienced by the writer. Moreover, Reymont never formulated an aesthetic of his writing. In that, he resembled other Polish autodidacts such as

Critics admit a number of similarities between Reymont and the Naturalists. They stress that this was not a "borrowed" Naturalism but rather a record of life as experienced by the writer. Moreover, Reymont never formulated an aesthetic of his writing. In that, he resembled other Polish autodidacts such as

Reymont's last book, ''Bunt'' (''Revolt''), serialized in 1922 and published in book form in 1924, describes a revolt by animals which take over their farm in order to introduce "equality". The revolt quickly degenerates into abuse and bloody terror.

The story was a metaphor for the

Reymont's last book, ''Bunt'' (''Revolt''), serialized in 1922 and published in book form in 1924, describes a revolt by animals which take over their farm in order to introduce "equality". The revolt quickly degenerates into abuse and bloody terror.

The story was a metaphor for the

Reymont pages at University of Buffalo's Polish Info Center

Władysław Stanislaw Reymont

at Culture.pl *

List of Works

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Reymont, Wladyslaw 1867 births 1925 deaths 19th-century Polish novelists 20th-century Polish novelists Polish male novelists Nobel laureates in Literature Polish cooperative organizers Polish Nobel laureates People from Radomsko Burials at Powązki Cemetery 19th-century male writers Recipients of the Order of Polonia Restituta

noble

A noble is a member of the nobility.

Noble may also refer to:

Places Antarctica

* Noble Glacier, King George Island

* Noble Nunatak, Marie Byrd Land

* Noble Peak, Wiencke Island

* Noble Rocks, Graham Land

Australia

* Noble Island, Gr ...

family, Reymont was educated to become a master tailor

A tailor is a person who makes or alters clothing, particularly in men's clothing. The Oxford English Dictionary dates the term to the thirteenth century.

History

Although clothing construction goes back to prehistory, there is evidence of ...

, but instead worked as a gateman at a railway station and then as an actor in a troupe. His intensive travels and voyages encouraged him to publish short stories

A short story is a piece of prose fiction that typically can be read in one sitting and focuses on a self-contained incident or series of linked incidents, with the intent of evoking a single effect or mood. The short story is one of the oldest t ...

, with notions of literary realism

Literary realism is a literary genre, part of the broader realism in arts, that attempts to represent subject-matter truthfully, avoiding speculative fiction and supernatural elements. It originated with the realist art movement that began with ...

. Reymont's first successful and widely praised novel was '' The Promised Land'' from 1899, which brought attention to the bewildering social inequalities, poverty, conflictive multiculturalism and labour exploitation in the industrial city of Łódź

Łódź, also rendered in English as Lodz, is a city in central Poland and a former industrial centre. It is the capital of Łódź Voivodeship, and is located approximately south-west of Warsaw. The city's coat of arms is an example of cant ...

(Lodz). The aim of the novel was to extensively emphasize the consequences of extreme industrialization and how it affects society

A society is a group of individuals involved in persistent social interaction, or a large social group sharing the same spatial or social territory, typically subject to the same political authority and dominant cultural expectations. Soci ...

as a whole. In 1900, Reymont was severely injured in a railway accident, which halted his writing career until 1904 when he published the first part of ''Chłopi''.

Władysław Reymont was popular in communist Poland

The Polish People's Republic ( pl, Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa, PRL) was a country in Central Europe that existed from 1947 to 1989 as the predecessor of the modern Republic of Poland. With a population of approximately 37.9 million nea ...

due to his style of writing and the symbolism

Symbolism or symbolist may refer to:

Arts

* Symbolism (arts), a 19th-century movement rejecting Realism

** Symbolist movement in Romania, symbolist literature and visual arts in Romania during the late 19th and early 20th centuries

** Russian sym ...

he used, including socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

concepts, romantic portrayal of the agrarian countryside and toned criticism of capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, price system, priva ...

, all present in literary realism. His work is widely attributed to the Young Poland

Young Poland ( pl, Młoda Polska) was a modernist period in Polish visual arts, literature and music, covering roughly the years between 1890 and 1918. It was a result of strong aesthetic opposition to the earlier ideas of Positivism. Young Pol ...

movement, which featured decadence

The word decadence, which at first meant simply "decline" in an abstract sense, is now most often used to refer to a perceived decay in standards, morals, dignity, religious faith, honor, discipline, or skill at governing among the members ...

and literary impressionism.

Surname

Reymont's baptism certificate gives his birth name as Stanisław Władysław Rejment. The change of surname from "Rejment" to "Reymont" was made by the author himself during his publishing debut, as it was supposed to protect him, in the Russian sector of partitioned Poland, from any potential trouble for having already published inAustrian Galicia

The Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria,, ; pl, Królestwo Galicji i Lodomerii, ; uk, Королівство Галичини та Володимирії, Korolivstvo Halychyny ta Volodymyrii; la, Rēgnum Galiciae et Lodomeriae also known as ...

a work not allowed under the Tsar's censorship. Kazimierz Wyka, an enthusiast of Reymont's work, believes that the alteration could also have been intended to remove any association with the word ''rejmentować'', which in some local Polish dialects means "to swear".

Life

Reymont was born in the village of Kobiele Wielkie, nearRadomsko

Radomsko is a city in southern Poland with 44,700 inhabitants (2021). It is situated on the Radomka river in the Łódź Voivodeship (since 1999), having previously been in Piotrków Voivodeship, Piotrków Trybunalski Voivodeship (1975–1998). ...

, as one of the nine children of Józef Rejment, an organist. His mother, Antonina Kupczyńska, had a talent for story-telling. She descended from the impoverished Polish nobility from the Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland until 1596 ...

region. Reymont spent his childhood in Tuszyn

Tuszyn is a small town in Łódź East County, Łódź Voivodeship, central Poland, with 7,237 inhabitants (2020).

Climate

Tuszyn has a humid continental climate (''Cfb'' in the Köppen climate classification

The Köppen climate classificat ...

, near Łódź

Łódź, also rendered in English as Lodz, is a city in central Poland and a former industrial centre. It is the capital of Łódź Voivodeship, and is located approximately south-west of Warsaw. The city's coat of arms is an example of cant ...

, to which his father had moved to work at a wealthier church parish. Reymont was defiantly stubborn; after a few years of education in the local school, he was sent by his father to Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is officia ...

into the care of his eldest sister and her husband to teach him his vocation. In 1885, after passing his examinations and presenting "a tail-coat, well-made", he was given the title of journeyman tailor, his only formal certificate of education.

To his family's annoyance, Reymont did not work a single day as a tailor. Instead, he first ran away to work in a travelling provincial theatre and then returned in the summer to Warsaw for the "garden theatres". Without a penny to his name, he then returned to Tuszyn after a year, and, thanks to his father's connections, he took up employment as a gateman at a railway crossing near Koluszki

Koluszki is a town, and a major railway junction, in central Poland, in Łódź Voivodeship, about 20 km east of Łódź with a population of 12,776 (2020). The junction in Koluszki serves trains that go from Warsaw to Łódź, Wrocław, Cz ...

for 16 rubles a month. He ran away twice more: in 1888 to Paris and London as a medium with a German spiritualist and then again to join a theatre troupe. After his lack of success (he was not a talented actor), he returned home again. Reymont also stayed for a time in Krosnowa near Lipce and for a time considered joining the Pauline Order

The Order of Saint Paul the First Hermit ( lat, Ordo Fratrum Sancti Pauli Primi Eremitæ; abbreviated OSPPE), commonly called the Pauline Fathers, is a monastic order of the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as th ...

in Częstochowa. He also lived in Kołaczkowo, where he bought a mansion.

Work

When his ''Korespondencje'' (''Correspondence'') from Rogów,

When his ''Korespondencje'' (''Correspondence'') from Rogów, Koluszki

Koluszki is a town, and a major railway junction, in central Poland, in Łódź Voivodeship, about 20 km east of Łódź with a population of 12,776 (2020). The junction in Koluszki serves trains that go from Warsaw to Łódź, Wrocław, Cz ...

and Skierniewice

Skierniewice is a city in central Poland with 47,031 inhabitants (2021), situated in the Łódź Voivodeship (since 1999), previously capital of Skierniewice Voivodeship (1975–1998). It is the capital of Skierniewice County. The town is situat ...

was accepted for publication by ''Głos'' (''The Voice'') in Warsaw in 1892, he returned to Warsaw, with several unpublished short stories and just a few rubles. Reymont visited the editorial offices of newspapers and magazines, and eventually met other writers who became interested in his talent including Świętochowski. In 1894 he went on an eleven-day pilgrimage to Częstochowa and turned his experience there into a report entitled "Pielgrzymka do Jasnej Góry" (Pilgrimage to the Luminous Mount) published in 1895, and considered his classic example of travel writing.

Rejmont sent his short stories to different magazines and, encouraged by good reviews, decided to write novels: ''Komediantka'' (''The Deceiver'') (1895) and ''Fermenty'' (''Ferments'') (1896). No longer poor, he would soon satisfy his passion for travel, visiting Berlin, London, Paris, and Italy. Then, he spent a few months in Łódź collecting material for a new novel ordered by the ''Kurier Codzienny'' (''The Daily Courier'') from Warsaw. The earnings from this book '' Ziemia Obiecana'' (''The Promised Land'') (1899) enabled him to go on his next trip to France where he socialized with other exiled Poles ( Jan Lorentowicz, Żeromski, Przybyszewski and Lucjan Rydel

Lucjan Rydel, also known as Lucjan Antoni Feliks Rydel (17 May 1870 in Kraków – 8 April 1918 in Bronowice Małe), was a Polish playwright and poet from the Young Poland movement.

Life

Rydel was the son of Lucjan Rydel, a surgeon, ophthalmolo ...

).

His earnings did not allow for this kind of life of travel. However, in 1900 he was awarded 40,000 rubles in compensation from the Warsaw-Vienna Railway after an accident in which Reymont was severely injured. During the treatment he was looked after by Aurelia Szacnajder Szabłowska, whom he married in 1902, having first paid for the annulment of her earlier marriage. Thanks to her discipline, he marginally restrained his travel-mania, but never gave up either his stays in France (where he partly wrote ''Chłopi'' between 1901 and 1908) or in Zakopane

Zakopane ( Podhale Goral: ''Zokopane'') is a town in the extreme south of Poland, in the southern part of the Podhale region at the foot of the Tatra Mountains. From 1975 to 1998, it was part of Nowy Sącz Voivodeship; since 1999, it has been ...

. Rejmont also journeyed to the United States in 1919 at the (Polish) government's expense. Despite his ambitions to become a landowner, which led to an unsuccessful attempt to manage an estate he bought in 1912 near Sieradz

Sieradz ( la, Siradia, yi, שעראַדז, שערעדז, שעריץ, german: 1941-45 Schieratz) is a city on the Warta river in central Poland with 40,891 inhabitants (2021). It is the seat of the Sieradz County, situated in the Łódź Voivode ...

, the life of the land proved not to be for him. He would later buy a mansion in Kołaczkowo near Poznań

Poznań () is a city on the River Warta in west-central Poland, within the Greater Poland region. The city is an important cultural and business centre, and one of Poland's most populous regions with many regional customs such as Saint Joh ...

in 1920, but still spent his winters in Warsaw or France.

Nobel Prize

In November 1924 he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature over rivals

In November 1924 he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature over rivals Thomas Mann

Paul Thomas Mann ( , ; ; 6 June 1875 – 12 August 1955) was a German novelist, short story writer, social critic, philanthropist, essayist, and the 1929 Nobel Prize in Literature laureate. His highly symbolic and ironic epic novels and novell ...

, George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw (26 July 1856 – 2 November 1950), known at his insistence simply as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from ...

and Thomas Hardy, after he had been nominated by Anders Österling

Anders Österling (13 April 1884 – 13 December 1981) was a Swedish poet, critic and translator. In 1919 he was elected as a member of the Swedish Academy when he was 35 years old and served the Academy for 62 years, longer than any other memb ...

, member of the Swedish Academy. Public opinion in Poland supported this recognition for Stefan Żeromski

Stefan Żeromski ( ; 14 October 1864 – 20 November 1925) was a Polish novelist and dramatist belonging to the Young Poland movement at the turn of the 20th century. He was called the "conscience of Polish literature".

He also wrote under ...

, but the prize went to the author of ''Chłopi''. Żeromski was reportedly refused for his allegedly anti-German sentiments. However, Reymont could not take part in the award ceremony in Sweden due to a heart condition. The award and the check for 116,718 Swedish kronor were sent to Reymont in France, where he was being treated.

In 1925, somewhat recovered, he went to a farmers' meeting in Wierzchosławice near Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland until 1596 ...

, where Wincenty Witos welcomed him as a member of the Polish People's Party

The Polish People's Party ( pl, Polskie Stronnictwo Ludowe, PSL) is an agrarian political party in Poland. It is currently led by Władysław Kosiniak-Kamysz.

Its history traces back to 1895, when it held the name People's Party, although i ...

"Piast" and praised his writing skills. Soon afterward, Reymont's health deteriorated. He died in Warsaw in December 1925 and was buried in the Powązki Cemetery

Powązki Cemetery (; pl, Cmentarz Powązkowski), also known as Stare Powązki ( en, Old Powązki), is a historic necropolis located in Wola district, in the western part of Warsaw, Poland. It is the most famous cemetery in the city and one of t ...

. The urn holding his heart was laid in a pillar of the Holy Cross Church in Warsaw.

Reymont's literary output includes about 30 extensive volumes of prose. There are works of reportage: ''Pielgrzymka do Jasnej Góry'' (''Pilgrimage to Jasna Góra'') (1894), ''Z ziemi chełmskiej'' (''From the Chełm Lands'') (1910 – about the persecutions of the Uniates), ''Z konstytucyjnych dni'' (''From the Days of the Constitution'') (about the revolution of 1905). Also, there are some sketches from the collection ''Za frontem'' (''Beyond the Front'') (1919) and numerous short stories on life in the theatre and the village or on the railway: "Śmierć" ("Death") (1893), "Suka" ("Bitch") (1894), "Przy robocie" ("At Work") and "W porębie" ("In the Clearing") (1895), "Tomek Baran" (1897), "Sprawiedliwie" ("Justly") (1899) and a sketch for a novel ''Marzyciel'' (''Dreamer'') (1908). There are also novels: ''Komediantka'', ''Fermenty'', ''Ziemia obiecana'', ''Chłopi'', ''Wampir'' (''The Vampire'') (1911), which were sceptically received by the critics, and a trilogy written in the years 1911–1917: ''Rok 1794'' (''1794'') (''Ostatni Sejm Rzeczypospolitej'', ''Nil desperandum'' and ''Insurekcja'') (''The Last Parliament of the Commonwealth'', ''Nil desperandum'' and ''Insurrection'').

Major books

Critics admit a number of similarities between Reymont and the Naturalists. They stress that this was not a "borrowed" Naturalism but rather a record of life as experienced by the writer. Moreover, Reymont never formulated an aesthetic of his writing. In that, he resembled other Polish autodidacts such as

Critics admit a number of similarities between Reymont and the Naturalists. They stress that this was not a "borrowed" Naturalism but rather a record of life as experienced by the writer. Moreover, Reymont never formulated an aesthetic of his writing. In that, he resembled other Polish autodidacts such as Mikołaj Rej

Mikołaj Rej or Mikołaj Rey of Nagłowice (4 February 1505 – between 8 September/5 October 1569) was a Polish poet and prose writer of the emerging Renaissance in Poland as it succeeded the Middle Ages, as well as a politician and musician. ...

and Aleksander Fredro

Aleksander Fredro (20 June 1793 – 15 July 1876) was a Polish poet, playwright and author active during Polish Romanticism in the period of partitions by neighboring empires. His works including plays written in the octosyllabic verse (''Zemst ...

. With little higher education and inability to read another language, Reymont realized that it was his knowledge of grounded reality, not literary theory, that was his strong suit.

His novel ''Komediantka'' paints the drama of a rebellious girl from the provinces who joins a traveling theatre troupe and finds, instead of escape from the mendacity of her native surroundings, a nest of intrigue and sham. In ''Fermenty'', a sequel to ''Komediantka'', the heroine, rescued after a suicide attempt, returns to her family and accepts the burden of existence. Aware that dreams and ideas do not come true, she marries a ''nouveau riche

''Nouveau riche'' (; ) is a term used, usually in a derogatory way, to describe those whose wealth has been acquired within their own generation, rather than by familial inheritance. The equivalent English term is the "new rich" or "new money" ( ...

'' who is in love with her.

'' Ziemia Obiecana'' (''The Promised Land''), possibly Reymont's best-known novel, is a social panorama of the city of Łódź

Łódź, also rendered in English as Lodz, is a city in central Poland and a former industrial centre. It is the capital of Łódź Voivodeship, and is located approximately south-west of Warsaw. The city's coat of arms is an example of cant ...

during the industrial revolution, full of dramatic detail, presented as an arena of the struggle for survival. In the novel, the city destroys those who accept the rules of the "rat race", as well as those who do not. The moral gangrene equally affects the three main characters, a German, a Jew, and a Pole. This dark vision of cynicism, illustrating the bestial qualities of men and the law of the jungle, where ethics, noble ideas and holy feelings turn against those who believe in them, are, as the author intended, at the same time a denunciation of industrialisation and urbanisation.

'' Ziemia Obiecana'' has been translated into at least 15 languages and two film adaptations—one in 1927, directed by A. Węgierski and A. Hertz, the other, in 1975, directed by Andrzej Wajda

Andrzej Witold Wajda (; 6 March 1926 – 9 October 2016) was a Polish film and theatre director. Recipient of an Honorary Oscar, the Palme d'Or, as well as Honorary Golden Lion and Honorary Golden Bear Awards, he was a prominent member of the ...

.

In ''Chłopi'', Reymont created a more complete and suggestive picture of country life than any other Polish writer. The novel impresses the reader with its authenticity of the material reality, customs, behaviour and spiritual culture of the people. It is authentic and written in the local dialect. Reymont uses dialect in dialogues and in narration, creating a kind of a universal language of Polish peasants. Thanks to this, he presents the colourful reality of the "spoken" culture of the people better than any other author. He set the action in Lipce, a real village which he came to know during his work on the railway near Skierniewice, and restricted the time of events to ten months in the unspecified "now" of the 19th century. It is not history that determines the rhythm of country life, but the "unspecified time" of eternal returns. The composition of the novel astonishes the reader with its strict simplicity and functionality.

The titles of the volumes signal a tetralogy in one vegetational cycle, which regulates the eternal and repeatable rhythm of village life. Parallel to that rhythm is a calendar of religion and customs, also repeatable. In such boundaries Reymont placed a colourful country community with sharply drawn individual portraits. The repertoire of human experience and the richness of spiritual life, which can be compared with the repertoire of Biblical books and Greek myths, has no doctrinal ideas or didactic exemplifications. The author does not believe in doctrines, but rather in his knowledge of life, the mentality of the people described, and his sense of reality. It is easy to point to moments of Naturalism (e.g., some erotic elements) or to illustrative motives characteristic of Symbolism

Symbolism or symbolist may refer to:

Arts

* Symbolism (arts), a 19th-century movement rejecting Realism

** Symbolist movement in Romania, symbolist literature and visual arts in Romania during the late 19th and early 20th centuries

** Russian sym ...

. It is equally easy to prove the Realistic values of the novel. None of the "isms" however, would be enough to describe it. The novel was filmed twice (directed by E. Modzelewski in 1922 and by J. Rybkowski in 1973) and has been translated into at least 27 languages.

''Revolt''

Reymont's last book, ''Bunt'' (''Revolt''), serialized in 1922 and published in book form in 1924, describes a revolt by animals which take over their farm in order to introduce "equality". The revolt quickly degenerates into abuse and bloody terror.

The story was a metaphor for the

Reymont's last book, ''Bunt'' (''Revolt''), serialized in 1922 and published in book form in 1924, describes a revolt by animals which take over their farm in order to introduce "equality". The revolt quickly degenerates into abuse and bloody terror.

The story was a metaphor for the Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

Revolution of 1917

The Russian Revolution was a period of political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and adopt a socialist form of government ...

and was banned from 1945 to 1989 in communist Poland, along with George Orwell's similar novella, ''Animal Farm

''Animal Farm'' is a beast fable, in the form of satirical allegorical novella, by George Orwell, first published in England on 17 August 1945. It tells the story of a group of farm animals who rebel against their human farmer, hoping to c ...

'' (published in Britain in 1945). Reymont's novel was reprinted in Poland in 2004.

Works

* ''Pielgrzymka do Jasnej Góry'' (''A Pilgrimage to Jasna Góra'', 1895) * ' (''The Deceiver'', 1896) * ''Fermenty'' (''Ferments'', 1897) * '' Ziemia obiecana'' (''The Promised Land'', 1898) * ''Lili : żałosna idylla (Lily: A Pathetic Idyll 1899)'' * ''Sprawiedliwie (Justly, 1899)'' * ''Na Krawędzi: Opowiadania (On the Edge: Stories, 1907)'' * '' Chłopi'' (''The Peasants'', 1904–1909), Nobel Prize for Literature, 1924 * ''Marzyciel'' (''The Dreamer'', 1910), * '' Rok 1794'' (1794, 1914–1919) ** Part I: ''Ostatni Sejm Rzeczypospolitej'' (''The LastSejm

The Sejm (English: , Polish: ), officially known as the Sejm of the Republic of Poland ( Polish: ''Sejm Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej''), is the lower house of the bicameral parliament of Poland.

The Sejm has been the highest governing body of ...

of the Republic'')

** Part II: ''Nil desperandum! '' (''Never Despair!'')

** Part III: ''Insurekcja'' (''The Uprising''), about the Kościuszko Uprising

* '' Wampir – powieść grozy'' (''The Vampire'', 1911)

* ''Przysiega'' (''Oaths'', 1917)

* '' Bunt'' (''The Revolt'', 1924)

English translations

* ''The Comédienne (Komediantka)'' translated by Edmund Obecny (1920) * '' The Peasants (Chłopi)'' translated by Michael Henry Dziewicki (1924–1925); translated by Anna Zaranko (2022) * '' The Promised Land (Ziemia obiecana)'' translated by Michael Henry Dziewicki (1927) * ''Polish Folklore Stories'' (1944) * ''Burek The Dog That Followed the Lord Jesus and Other Stories'' (1944) * '' A Pilgrimage to Jasna Góra'' (''Pielgrzymka do Jasnej Góry'') translated by Filip Mazurczak (2020)See also

*Fable

Fable is a literary genre: a succinct fictional story, in prose or verse (poetry), verse, that features animals, legendary creatures, plants, inanimate objects, or forces of nature that are Anthropomorphism, anthropomorphized, and that illustrat ...

*Young Poland

Young Poland ( pl, Młoda Polska) was a modernist period in Polish visual arts, literature and music, covering roughly the years between 1890 and 1918. It was a result of strong aesthetic opposition to the earlier ideas of Positivism. Young Pol ...

*List of Polish writers

Notable Polish novelists, poets, playwrights, historians and philosophers, listed in chronological order by year of birth:

* (''ca.''1465–after 1529) Biernat of Lublin

* (1482–1537) Andrzej Krzycki

* (1503–1572) Andrzej Frycz Modrzewski

...

*List of Polish Nobel laureates

This is a list of Nobel laureates who are Poles (ethnic) or Polish (citizenship). The Nobel Prize is a set of annual international awards bestowed on "those who conferred the greatest benefit on humankind", first instituted in 1901. Since 1903, t ...

References

External links

*Reymont pages at University of Buffalo's Polish Info Center

Władysław Stanislaw Reymont

at Culture.pl *

List of Works

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Reymont, Wladyslaw 1867 births 1925 deaths 19th-century Polish novelists 20th-century Polish novelists Polish male novelists Nobel laureates in Literature Polish cooperative organizers Polish Nobel laureates People from Radomsko Burials at Powązki Cemetery 19th-century male writers Recipients of the Order of Polonia Restituta