Władysław Gomułka on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Władysław Gomułka (; 6 February 1905 – 1 September 1982) was a

Gomułka was a deputy prime minister in the Provisional Government of the Republic of Poland (''Rząd Tymczasowy Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej''), from January to June 1945, and in the

Gomułka was a deputy prime minister in the Provisional Government of the Republic of Poland (''Rząd Tymczasowy Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej''), from January to June 1945, and in the

at

In June 1956, violent worker protests broke out in

In June 1956, violent worker protests broke out in

In December 1970, economic difficulties led to price rises and subsequent

In December 1970, economic difficulties led to price rises and subsequent

Order of the Builders of People's Poland

**

Order of the Builders of People's Poland

** Grand Cross of the

Grand Cross of the  Order of the Cross of Grunwald (1st class)

**

Order of the Cross of Grunwald (1st class)

** Partisan Cross

**

Partisan Cross

** Medal "For Warsaw 1939-1945"

**

Medal "For Warsaw 1939-1945"

** Medal Rodła

*Other countries:

**

Medal Rodła

*Other countries:

** Grand Cross of the

Grand Cross of the  Knight Grand Cross with Collar of the

Knight Grand Cross with Collar of the

Polish communist

Communism in Poland can trace its origins to the late 19th century: the Marxist First Proletariat party was founded in 1882. Rosa Luxemburg (1871–1919) of the Social Democracy of the Kingdom of Poland and Lithuania (''Socjaldemokracja Króles ...

politician. He was the ''de facto

''De facto'' ( ; , "in fact") describes practices that exist in reality, whether or not they are officially recognized by laws or other formal norms. It is commonly used to refer to what happens in practice, in contrast with '' de jure'' ("by l ...

'' leader of post-war Poland from 1947 until 1948. Following the Polish October

Polish October (), also known as October 1956, Polish thaw, or Gomułka's thaw, marked a change in the politics of Poland in the second half of 1956. Some social scientists term it the Polish October Revolution, which was less dramatic than the ...

he became leader again from 1956 to 1970. Gomułka was initially very popular for his reforms; his seeking a "Polish way to socialism

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes th ...

"; and giving rise to the period known as "Polish thaw

Polish October (), also known as October 1956, Polish thaw, or Gomułka's thaw, marked a change in the politics of Poland in the second half of 1956. Some social scientists term it the Polish October Revolution, which was less dramatic than the ...

". During the 1960s, however, he became more rigid and authoritarian—afraid of destabilizing the system, he was not inclined to introduce or permit changes. In the 1960s he supported the persecution of the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwide . It is am ...

, intellectuals and the anti-communist opposition.

In 1967 to 1968, Gomułka allowed outbursts of anti-Zionist and antisemitic political campaign, pursued primarily by others in the Party, but utilized by Gomułka to retain power by shifting the attention from the stagnating economy. Many of the remaining Polish Jews

The history of the Jews in Poland dates back at least 1,000 years. For centuries, Poland was home to the largest and most significant Ashkenazi Jewish community in the world. Poland was a principal center of Jewish culture, because of the l ...

left the country. At that time he was also responsible for persecuting protesting students and toughening censorship of the media. Gomułka supported Poland's participation in the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia

The Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia refers to the events of 20–21 August 1968, when the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic was jointly invaded by four Warsaw Pact countries: the Soviet Union, the Polish People's Republic, the People's Rep ...

in August 1968.

In the treaty with West Germany, signed in December 1970 at the end of Gomułka's period in office, West Germany recognized the post-World War II borders, which established a foundation for future peace, stability and cooperation in Central Europe

Central Europe is an area of Europe between Western Europe and Eastern Europe, based on a common historical, social and cultural identity. The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) between Catholicism and Protestantism significantly shaped the a ...

. In the same month, economic difficulties led to price rises and subsequent bloody clashes with shipyard

A shipyard, also called a dockyard or boatyard, is a place where ships are built and repaired. These can be yachts, military vessels, cruise liners or other cargo or passenger ships. Dockyards are sometimes more associated with maintenance ...

workers on the Baltic coast

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from 10 ...

, in which several dozen workers were fatally shot. The tragic events forced Gomułka's resignation and retirement. In a generational replacement of the ruling elite, Edward Gierek

Edward Gierek (; 6 January 1913 – 29 July 2001) was a Polish Communist politician and ''de facto'' leader of Poland between 1970 and 1980. Gierek replaced Władysław Gomułka as First Secretary of the ruling Polish United Workers' Party (P ...

took over the Party leadership and tensions eased.

Childhood and education

Władysław Gomułka was born on 6 February 1905 in Białobrzegi Franciszkańskie village on the outskirts ofKrosno

Krosno (in full ''The Royal Free City of Krosno'', pl, Królewskie Wolne Miasto Krosno) is a historical town and county in the Subcarpathian Voivodeship, in southeastern Poland. The estimated population of the town is 47,140 inhabitants as of 2 ...

, into a worker's family living in the Austrian Partition

The Austrian Partition ( pl, zabór austriacki) comprise the former territories of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth acquired by the Habsburg monarchy during the Partitions of Poland in the late 18th century. The three partitions were conduct ...

(the Galicia

Galicia may refer to:

Geographic regions

* Galicia (Spain), a region and autonomous community of northwestern Spain

** Gallaecia, a Roman province

** The post-Roman Kingdom of the Suebi, also called the Kingdom of Gallaecia

** The medieval King ...

region). His parents had met and married in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

, where each had immigrated to in search of work in the late 19th century, but returned to occupied Poland in the early 20th century because Władysław's father Jan was unable to find gainful employment in America. Jan Gomułka then worked as a laborer in the Subcarpathian oil industry. Władysław's older sister Józefa, born in the US, returned there upon turning eighteen to join her extended family, most of whom had emigrated, and to preserve her US citizenship. Władysław and his two other siblings experienced a childhood of the proverbial Galician poverty: they lived in a dilapidated hut and ate mostly potatoes. Władysław received only rudimentary education before being employed in the oil industry of the region.

Gomułka attended schools in Krosno for six or seven years, until the age of thirteen when he had to start an apprenticeship in a metalworks shop. Throughout his life Gomułka was an avid reader and accomplished a great deal of self-education, but remained a subject of jokes because of his lack of formal education and demeanor. In 1922, Gomułka passed his apprenticeship exams and began working at a local refinery.

Early revolutionary activities

Involvement with labor unions and first imprisonment

The re-established Polish state of Gomułka's teen years was a scene of growing political polarization and radicalization. The young worker developed connections with the radicalLeft

Left may refer to:

Music

* ''Left'' (Hope of the States album), 2006

* ''Left'' (Monkey House album), 2016

* "Left", a song by Nickelback from the album '' Curb'', 1996

Direction

* Left (direction), the relative direction opposite of right

* ...

, joining the ''Siła'' (Power) youth organization in 1922 and the Independent Peasant Party in 1925. Gomułka was known for his activism in the metal workers and, from 1922, chemical industry unions. He was involved in union-organized strikes and in 1924, during a protest gathering in Krosno, participated in a polemical debate with Herman Lieberman. He published radical texts in leftist newspapers. In May 1926 the young Gomułka was for the first time arrested but soon released because of worker demands. The incident was the subject of a parliamentary intervention by the Peasant Party. In October 1926, Gomułka became a secretary of the managing council in the Chemical Industry Workers Union for the Drohobych

Drohobych ( uk, Дрого́бич, ; pl, Drohobycz; yi, דראָהאָביטש;) is a city of regional significance in Lviv Oblast, Ukraine. It is the administrative center of Drohobych Raion and hosts the administration of Drohobych urban h ...

District and remained involved with that communist-dominated union until 1930. He around this time learned on his own basic Ukrainian

Ukrainian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Ukraine

* Something relating to Ukrainians, an East Slavic people from Eastern Europe

* Something relating to demographics of Ukraine in terms of demography and population of Ukraine

* So ...

.

In late 1926, while in Drohobych, Gomułka became a member of the illegal-but-functioning Communist Party of Poland

The interwar Communist Party of Poland ( pl, Komunistyczna Partia Polski, KPP) was a communist party active in Poland during the Second Polish Republic. It resulted from a December 1918 merger of the Social Democracy of the Kingdom of Poland a ...

(''Komunistyczna Partia Polski'', KPP) and was arrested for political agitation. Technically, at this time he was a member of the Communist Party of Western Ukraine Communist Party of Western Ukraine (; uk, Комуністична партія Західної України) was a political party in eastern interwar Poland. Until 1923 it was known as the Communist Party of Eastern Galicia (Komunistyczna Par ...

, which was an autonomous branch of the Communist Party of Poland. He was interested primarily in social issues, including the trade and labor movement, and concentrated on practical activities. In mid-1927, Gomułka was brought to Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is officiall ...

, where he remained active until drafted for military service at the end of the year. After several months, the military released him because of a health problem with his right leg. Gomułka returned to communist party work, organizing strike actions and speaking at gatherings of workers at all major industrial centers of Poland. During this period he was arrested several times and lived under police supervision.

Gomułka was an activist in the leftist labor unions from 1926 and in the Central Trade Department of the KPP Central Committee

Central committee is the common designation of a standing administrative body of communist parties, analogous to a board of directors, of both ruling and nonruling parties of former and existing socialist states. In such party organizations, the ...

from 1931. In the summer of 1930, Gomułka illegally embarked on his first foreign trip with the intention of participating in the Red International of Labor Unions

The Red International of Labor Unions (russian: Красный интернационал профсоюзов, translit=Krasnyi internatsional profsoyuzov, RILU), commonly known as the Profintern, was an international body established by the Comm ...

Fifth Congress held in Moscow from 15 to 30 July. Traveling from Upper Silesia

Upper Silesia ( pl, Górny Śląsk; szl, Gůrny Ślůnsk, Gōrny Ślōnsk; cs, Horní Slezsko; german: Oberschlesien; Silesian German: ; la, Silesia Superior) is the southeastern part of the historical and geographical region of Silesia, locate ...

to Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitu ...

, he had to wait there for the issuance of Soviet documents and arrived in Moscow too late to participate in the deliberations of the Congress. He stayed in Moscow for a couple of weeks and then went to Leningrad

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

, from where he took a ship to Hamburg

Hamburg (, ; nds, label=Hamburg German, Low Saxon, Hamborg ), officially the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg (german: Freie und Hansestadt Hamburg; nds, label=Low Saxon, Friee un Hansestadt Hamborg),. is the List of cities in Germany by popul ...

, stayed in Berlin again and through Silesia returned to Poland.

In August 1932, he was arrested by the Sanation

Sanation ( pl, Sanacja, ) was a Polish political movement that was created in the interwar period, prior to Józef Piłsudski's May 1926 ''Coup d'État'', and came to power in the wake of that coup. In 1928 its political activists would go on ...

police while participating in a conference of textile

Textile is an Hyponymy and hypernymy, umbrella term that includes various Fiber, fiber-based materials, including fibers, yarns, Staple (textiles)#Filament fiber, filaments, Thread (yarn), threads, different #Fabric, fabric types, etc. At f ...

worker delegates in Łódź

Łódź, also rendered in English as Lodz, is a city in central Poland and a former industrial centre. It is the capital of Łódź Voivodeship, and is located approximately south-west of Warsaw. The city's coat of arms is an example of ca ...

. When he later tried to escape, Gomułka sustained a gunshot wound in the left thigh which ultimately left him with permanent walking impairment.

Journey to the Soviet Union and second imprisonment

Despite being sentenced to a four-year prison term on 1 June 1933, he was temporarily released for surgery on his injured leg in March 1934. Following his release, Gomułka requested that the KPP send him to the Soviet Union for medical treatment and further political training. He arrived in the Soviet Union in June and went to theCrimea

Crimea, crh, Къырым, Qırım, grc, Κιμμερία / Ταυρική, translit=Kimmería / Taurikḗ ( ) is a peninsula in Ukraine, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, that has been occupied by Russia since 2014. It has a p ...

for several weeks, where he underwent therapeutic baths. Gomułka then spent more than a year in Moscow, where he attended the Lenin School under the name Stefan Kowalski. The ideology-oriented classes were arranged separately for a small group of Polish students (one of them was Roman Romkowski

Roman Romkowski born Nasiek (Natan) Grinszpan-Kikiel, Tadeusz Piotrowski ''Poland's holocaust''. Page 60McFarland, 1998. . 437 pages. (February 16, 1907 – July 12, 1965) was a Polish communist official trained by Comintern in Moscow. After the ...

(Natan Grünspan rinszpanKikiel), who would later persecute Gomułka in Stalinist Poland) and included a military training course conducted by Karol Świerczewski

Karol Wacław Świerczewski (; callsign ''Walter''; 10 February 1897 – 28 March 1947) was a Polish and Soviet Red Army general and statesman. He was a Bolshevik Party member during the Russian Civil War and a Soviet officer in the wars foug ...

. In a written opinion issued by the school Gomułka was characterized in highly positive terms, but his extended stay in the Soviet Union caused him to become disillusioned with the realities of Stalinist communism and highly critical of the agrarian collectivization

Collective farming and communal farming are various types of, "agricultural production in which multiple farmers run their holdings as a joint enterprise". There are two broad types of communal farms: agricultural cooperatives, in which member- ...

practice. In November 1935 he illegally returned to Poland.

Gomułka resumed his communist and labor conspiratorial activities and kept advancing within the KPP organization until, as the secretary of the Party's Silesian branch, he was arrested in Chorzów

Chorzów ( ; ; german: link=no, Königshütte ; szl, Chorzōw) is a city in the Silesia region of southern Poland, near Katowice. Chorzów is one of the central cities of the Upper Silesian Metropolitan Union – a metropolis with a population ...

in April 1936. He was then tried by the District Court in Katowice

Katowice ( , , ; szl, Katowicy; german: Kattowitz, yi, קאַטעוויץ, Kattevitz) is the capital city of the Silesian Voivodeship in southern Poland and the central city of the Upper Silesian metropolitan area. It is the 11th most popu ...

and sentenced to seven years in prison where he remained jailed until the beginning of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

. Ironically, this internment most likely saved Gomułka's life, because the majority of the KPP leadership would be murdered in the Soviet Union in the late 1930s, caught up in the Great Purge

The Great Purge or the Great Terror (russian: Большой террор), also known as the Year of '37 (russian: 37-й год, translit=Tridtsat sedmoi god, label=none) and the Yezhovshchina ('period of Yezhov'), was Soviet General Secreta ...

under Joseph Stalin's orders.

Gomułka's experiences turned him into an extremely suspicious and distrustful person and contributed to his lifelong conviction that Sanation

Sanation ( pl, Sanacja, ) was a Polish political movement that was created in the interwar period, prior to Józef Piłsudski's May 1926 ''Coup d'État'', and came to power in the wake of that coup. In 1928 its political activists would go on ...

Poland was a fascist

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy and the ...

state, even if Polish prisons were the safest place for Polish Communists. He differentiated this belief from his positive feelings toward the country and its people, especially members of the working class

The working class (or labouring class) comprises those engaged in manual-labour occupations or industrial work, who are remunerated via waged or salaried contracts. Working-class occupations (see also " Designation of workers by collar colou ...

.

World War II

Invasion of Poland

The outbreak of the war with Nazi Germany freed Gomułka from his prison confinement. On 7 September 1939, he arrived in Warsaw, where he stayed for a few weeks, working in the besieged capital on the construction of defensive fortifications. From there, like many other Polish communists, Gomułka fled to eastern Poland which was invaded by the Soviet Union on 17 September 1939. InBiałystok

Białystok is the largest city in northeastern Poland and the capital of the Podlaskie Voivodeship. It is the tenth-largest city in Poland, second in terms of population density, and thirteenth in area.

Białystok is located in the Białystok U ...

he ran a home for former political prisoners arriving from other parts of Poland. To be reunited with his luckily found wife, at the end of 1939 Gomułka moved to Soviet-controlled Lviv

Lviv ( uk, Львів) is the largest city in Western Ukraine, western Ukraine, and the List of cities in Ukraine, seventh-largest in Ukraine, with a population of . It serves as the administrative centre of Lviv Oblast and Lviv Raion, and is o ...

.

Like other members of the dissolved Communist Party of Poland, Gomułka sought a membership in the Soviet All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks)

"Hymn of the Bolshevik Party"

, headquarters = 4 Staraya Square, Moscow

, general_secretary = Vladimir Lenin (first)Mikhail Gorbachev (last)

, founded =

, banned =

, founder = Vladimir Lenin

, newspaper ...

. The Soviet authorities allowed such membership transfers only from March 1941 and in April of that year Gomułka received his party card in Kiev

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the seventh-most populous city in Europe.

Ky ...

.

The circumstances of the Polish communists' lives changed dramatically after 1941 German attack on the Soviet positions in eastern Poland. Reduced to penury in now German-occupied Lviv, the Gomułkas managed to join Władysław's family in Krosno

Krosno (in full ''The Royal Free City of Krosno'', pl, Królewskie Wolne Miasto Krosno) is a historical town and county in the Subcarpathian Voivodeship, in southeastern Poland. The estimated population of the town is 47,140 inhabitants as of 2 ...

by the end of 1941. However, a momentous development soon took place in the sphere of communist political activity: in January 1942, Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet Union, Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as Ge ...

reestablished in Warsaw a Polish communist party under the name of the Polish Workers' Party

The Polish Workers' Party ( pl, Polska Partia Robotnicza, PPR) was a communist party in Poland from 1942 to 1948. It was founded as a reconstitution of the Communist Party of Poland (KPP) and merged with the Polish Socialist Party (PPS) in 194 ...

(PPR).

In 1942, Gomułka participated in the reformation of a Polish communist party (the KPP was destroyed in Stalin's purges

The Great Purge or the Great Terror (russian: Большой террор), also known as the Year of '37 (russian: 37-й год, translit=Tridtsat sedmoi god, label=none) and the Yezhovshchina ('period of Yezhov'), was Soviet General Secret ...

in the late 1930s) under the name Polish Workers' Party

The Polish Workers' Party ( pl, Polska Partia Robotnicza, PPR) was a communist party in Poland from 1942 to 1948. It was founded as a reconstitution of the Communist Party of Poland (KPP) and merged with the Polish Socialist Party (PPS) in 194 ...

(''Polska Partia Robotnicza'', PPR). Gomułka became involved in the creation of party structures in the Subcarpathian region and began using his wartime conspiratorial pseudonym "Wiesław". In July 1942, Paweł Finder

Paweł Finder (; born as ''Pinkus Finder''; pseudonyms: ''Paul Finder'', ''Paul Reynot''; 19 September 1904 – 26 July 1944) was a Polish Communist leader and First Secretary of the Polish Workers' Party (PPR) from 1943 to 1944.Dia–pozytywPa ...

brought Gomułka to occupied Warsaw. In August, the secretary of the PPR's regional Warsaw Committee was arrested by the Gestapo

The (), abbreviated Gestapo (; ), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of Prussia into one orga ...

and "Wiesław" was entrusted with his job. In September Gomułka became a member of the PPR's Temporary Central Committee.

In late 1942 and early 1943, the PPR experienced a severe crisis because of the murder of its first secretary Marceli Nowotko. Gomułka participated in the party investigation directed against another member of the leadership, Bolesław Mołojec, that resulted in Mołojec's execution. Together with Paweł Finder, who was made First Secretary of the party, and Franciszek Jóźwiak, Gomułka (under the pseudonym "Wiesław") was included in the Party's new inner leadership, established in January 1943. The Central Committee was enlarged in the following months to include Bolesław Bierut

Bolesław Bierut (; 18 April 1892 – 12 March 1956) was a Polish communist activist and politician, leader of the Polish People's Republic from 1947 until 1956. He was President of the State National Council from 1944 to 1947, President of Po ...

, among others.

In February 1943, Gomułka led the communist side in a series of important meetings in Warsaw between the PPR and the Government Delegation of the London-based Polish government-in-exile

The Polish government-in-exile, officially known as the Government of the Republic of Poland in exile ( pl, Rząd Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej na uchodźstwie), was the government in exile of Poland formed in the aftermath of the Invasion of Pola ...

and the Home Army

The Home Army ( pl, Armia Krajowa, abbreviated AK; ) was the dominant resistance movement in German-occupied Poland during World War II. The Home Army was formed in February 1942 from the earlier Związek Walki Zbrojnej (Armed Resistance) es ...

. The talks produced no results because of the divergent interests of the parties involved and a mutual lack of confidence. The Delegation officially discontinued the negotiations on April 28, three days after the Soviet government broke diplomatic relations with the Polish government. He became the Party's main ideologist. He wrote the "What do we fight for?" (''O co walczymy?'') publication dated 1 March 1943, and the much more comprehensive declaration that emerged under the same title in November. "Wiesław" supervised the Party's main editorial and publishing undertaking.

Gomułka made efforts, largely unsuccessful, to secure for the PPR cooperation of other political forces in occupied Poland. Bierut, meanwhile, was indifferent to any such attempts and counted simply on compulsion provided by a future presence of the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian language, Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist R ...

in Poland. The different strategies resulted in a sharp conflict between the two communist politicians.

State National Council, Polish Committee of National Liberation

In the fall of 1943, the PPR leadership began discussing the creation of a Polish quasi-parliamentary, communist-led body, to be named the State National Council (''Krajowa Rada Narodowa'', KRN). After theBattle of Kursk

The Battle of Kursk was a major World War II Eastern Front engagement between the forces of Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union near Kursk in the southwestern USSR during late summer 1943; it ultimately became the largest tank battle in history ...

the expectation was of a Soviet victory and liberation of Poland and the PPR wanted to be ready to assume power. Gomułka came up with the idea of a national council and imposed his point of view on the rest of the leadership. The PPR intended to obtain consent from the Comintern

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a Soviet-controlled international organization founded in 1919 that advocated world communism. The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress to "struggle by ...

leader and their Soviet contact Georgi Dimitrov

Georgi Dimitrov Mihaylov (; bg, Гео̀рги Димитро̀в Миха̀йлов), also known as Georgiy Mihaylovich Dimitrov (russian: Гео́ргий Миха́йлович Дими́тров; 18 June 1882 – 2 July 1949), was a Bulgarian ...

. However, in November the Gestapo

The (), abbreviated Gestapo (; ), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of Prussia into one orga ...

arrested Finder and Małgorzata Fornalska, who possessed the secret codes for communication with Moscow and the Soviet response remained unknown. In the absence of Finder, on 23 November Gomułka was elected general secretary (chief) of the PPR and Bierut joined the three-person inner leadership.

The founding meeting of the State National Council took place in the late evening of 31 December 1943. The new body's chairman Bierut was becoming Gomułka's main rival. In mid-January 1944 Dimitrov was finally informed of the KRN's existence, which surprised both him and the Polish communist leaders in Moscow, increasingly led by Jakub Berman

Jakub Berman (23 December 1901 – 10 April 1984) was a Polish communist politician. Was born in Jewish family, son of Iser and Guta. An activist during the Second Polish Republic, in post-war communist Poland he was a member of the Politburo of ...

, who had other, competing ideas concerning the establishment of a Polish communist ruling party and government.

Gomułka felt that the Polish communists in occupied Poland had a better understanding of Polish realities than their brethren in Moscow and that the State National Council should determine the shape of the future executive government of Poland. Nevertheless, to gain Soviet approval and to clear any misunderstandings a KRN delegation left Warsaw in mid-March heading for Moscow, where it arrived two months later. By that time Stalin concluded that the existence of the KRN was a positive development and the Poles arriving from Warsaw were received and greeted by him and other Soviet dignitaries. The Union of Polish Patriots

Union of Polish Patriots (''Society of Polish Patriots'', pl, Związek Patriotów Polskich, ZPP, russian: Союз Польских Патриотов, СПП) was a political body created by Polish communists in the Soviet Union in 1943. The ...

and the Central Bureau of Polish Communists in Moscow were now under pressure to recognize the primacy of the PPR, the KRN and Władysław Gomułka, which they ultimately did only in mid-July.

On 20 July, the Soviet forces under Marshal Konstantin Rokossovsky

Konstantin Konstantinovich (Xaverevich) Rokossovsky ( Russian: Константин Константинович Рокоссовский; pl, Konstanty Rokossowski; 21 December 1896 – 3 August 1968) was a Soviet and Polish officer who bec ...

forced their way across the Bug River

uk, Західний Буг be, Захо́дні Буг

, name_etymology =

, image = Wyszkow_Bug.jpg

, image_size = 250

, image_caption = Bug River in the vicinity of Wyszków, Poland

, map = Vi ...

and on that same day the combined meeting of Polish communists from the Moscow and Warsaw factions finalized the arrangements regarding the establishment (on 21 July) of the Polish Committee of National Liberation

The Polish Committee of National Liberation (Polish: ''Polski Komitet Wyzwolenia Narodowego'', ''PKWN''), also known as the Lublin Committee, was an executive governing authority established by the Soviet-backed communists in Poland at the la ...

(PKWN), a temporary government headed by Edward Osóbka-Morawski

Edward Bolesław Osóbka-Morawski (5 October 1909 – 9 January 1997) was a Polish activist and politician in the Polish Socialist Party (PPS) before World War II, and after the Soviet takeover of Poland, Chairman of the Communist-dominated inte ...

, a socialist allied with the communists. Gomułka and other PPR leaders left Warsaw and headed for the Soviet-controlled territory, arriving in Lublin

Lublin is the ninth-largest city in Poland and the second-largest city of historical Lesser Poland. It is the capital and the center of Lublin Voivodeship with a population of 336,339 (December 2021). Lublin is the largest Polish city east of ...

on 1 August, the day the Warsaw Uprising

The Warsaw Uprising ( pl, powstanie warszawskie; german: Warschauer Aufstand) was a major World War II operation by the Polish underground resistance to liberate Warsaw from German occupation. It occurred in the summer of 1944, and it was led ...

erupted in the Polish capital.

Post-war political career

Role in communist takeover of Poland

Gomułka was a deputy prime minister in the Provisional Government of the Republic of Poland (''Rząd Tymczasowy Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej''), from January to June 1945, and in the

Gomułka was a deputy prime minister in the Provisional Government of the Republic of Poland (''Rząd Tymczasowy Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej''), from January to June 1945, and in the Provisional Government of National Unity

The Provisional Government of National Unity ( pl, Tymczasowy Rząd Jedności Narodowej - TRJN) was a puppet government formed by the decree of the State National Council () on 28 June 1945 as a result of reshuffling the Soviet-backed Provisio ...

(''Tymczasowy Rząd Jedności Narodowej''), from 1945 to 1947. As a minister of Recovered Territories

The Recovered Territories or Regained Lands ( pl, Ziemie Odzyskane), also known as Western Borderlands ( pl, Kresy Zachodnie), and previously as Western and Northern Territories ( pl, Ziemie Zachodnie i Północne), Postulated Territories ( pl, Z ...

(1945–48), he exerted great influence over the rebuilding, integration and economic progress of Poland within its new borders, by supervising the settlement, development and administration of the lands acquired from Germany. Using his position in the PPR and government, Gomułka led the leftist

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in so ...

social transformations in Poland and participated in the crushing of the resistance to communist rule during the post-war years. He also helped the communists in winning the '' Trzy razy tak'' ("Three Times Yes") referendum of 1946. A year later, he played a key role in the 1947 parliamentary elections, which were fraudulently arranged to give the communists and their allies an overwhelming victory. After the elections, all remaining legal opposition in Poland was effectively destroyed, and Gomułka was now the most powerful man in Poland. In June 1948, because of the impending unification of the PPR and PPS, Gomułka delivered a talk on the subject of the history of the Polish worker movement.

In a memo written to Stalin in 1948, Gomułka argued that "some of the Jewish comrades don't feel any link to the Polish nation or to the Polish working class … or they maintain a stance which might be described as ‘national nihilism’".Applebaum, Anne. ''Iron Curtain: The Crushing of Eastern Europe 1944–56.'' London: Penguin, 2013, p. 156 As a result, he considered it "absolutely necessary not only to stop any further growth in the percentage of Jews in the state as well as the party apparatus, but also to slowly lower that percentage, especially at the highest levels of the apparatus". Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev s ...

, who was intimately involved in Polish affairs in the 1940s, according to Khrushchev′s memoirs, believed that Gomułka had a valid point in opposing the personnel policies pursued by Roman Zambrowski

Roman Zambrowski (born Rubin Nassbaum; 15 July 1909 – 19 August 1977) was a Polish communist politician.

Career

Zambrowski was born into a Jewish family in Warsaw. He was a member of the Communist Party of Poland (1928–1938) and of the Cen ...

, Jakub Berman

Jakub Berman (23 December 1901 – 10 April 1984) was a Polish communist politician. Was born in Jewish family, son of Iser and Guta. An activist during the Second Polish Republic, in post-war communist Poland he was a member of the Politburo of ...

, and Hilary Minc

Hilary Minc (24 August 1905, Kazimierz Dolny – 26 November 1974, Warsaw) was a Polish economist and communist politician prominent in Stalinist Poland.

Minc was born into a middle class Jewish family; his parents were Oskar Minc and Stefa ...

, all of them of Jewish descent and brought to Poland from the Soviet Union. Nikita Sergeevich Khrushchev; Edward Crankshaw; Strobe Talbott

Nelson Strobridge Talbott III (born April 25, 1946) is an American foreign policy analyst focused on Russia. He was associated with '' Time'' magazine, and a diplomat who served as the Deputy Secretary of State from 1994 to 2001. He was presiden ...

; Jerrold L Schecter. Khrushchev remembers (volume 2): the last testament. London: Deutsch, 1974, pp. 222–224. Nevertheless, Khrushchev attributed Gomułka′s subsequent downfall to his rivals having succeeded in portraying Gomułka as being pro- Yugoslav; the charges were not made public but were brought to Stalin′s attention and became crucial in his decision-making on whose side he would support — in view of the Soviet–Yugoslavia rift that occurred in 1948.

Temporary withdrawal from politics

In the late 1940s, Poland's communist government was split by a rivalry between Gomułka and PresidentBolesław Bierut

Bolesław Bierut (; 18 April 1892 – 12 March 1956) was a Polish communist activist and politician, leader of the Polish People's Republic from 1947 until 1956. He was President of the State National Council from 1944 to 1947, President of Po ...

. Gomułka led a home national group while Bierut headed a group reared by Stalin in the Soviet Union. The struggle ultimately led to Gomułka's removal from power in 1948. While Bierut advocated a policy of complete subservience to Moscow, Gomułka wanted to adapt the Communist blueprint to Polish circumstances. Among other things, he opposed forced collectivization and was skeptical of the Cominform

The Information Bureau of the Communist and Workers' Parties (), commonly known as Cominform (), was a co-ordination body of Marxist-Leninist communist parties in Europe during the early Cold War that was formed in part as a replacement of the ...

. The Bierut faction had Stalin's ear, and on Stalin's orders, Gomułka was sacked as party leader for "rightist-nationalist deviation," replaced by Bierut. In December, soon after the PPR and Polish Socialist Party

The Polish Socialist Party ( pl, Polska Partia Socjalistyczna, PPS) is a socialist political party in Poland.

It was one of the most important parties in Poland from its inception in 1892 until its merger with the communist Polish Workers' ...

merged to form Polish United Workers' Party

The Polish United Workers' Party ( pl, Polska Zjednoczona Partia Robotnicza; ), commonly abbreviated to PZPR, was the communist party which ruled the Polish People's Republic as a one-party state from 1948 to 1989. The PZPR had led two other lega ...

(PZPR) (which was essentially the PPR under a new name), Gomułka was dropped from the merged party's Politburo. He was stripped of his remaining government posts in January 1949 and expelled from the party altogether in November. For the next eight years, he performed no official functions and was subjected to persecution, including almost four years of imprisonment from 1951 to 1954.Władysław Gomułkaat

Encyclopedia Britannica

An encyclopedia ( American English) or encyclopædia (British English) is a reference work or compendium providing summaries of knowledge either general or special to a particular field or discipline. Encyclopedias are divided into articl ...

Bierut died in March 1956, during a period of de-Stalinization

De-Stalinization (russian: десталинизация, translit=destalinizatsiya) comprised a series of political reforms in the Soviet Union after the death of long-time leader Joseph Stalin in 1953, and the thaw brought about by ascension ...

in Poland which gradually developed after Stalin's death. Edward Ochab

Edward Ochab (; 16 August 1906 – 1 May 1989) was a Polish communist politician and top leader of Poland between March and October 1956.

As a member of the Communist Party of Poland from 1929, he was repeatedly imprisoned for his activities u ...

became the new first secretary of the Party. Soon afterward, Gomułka was partially rehabilitated when Ochab conceded that Gomułka should not have been jailed, while reiterating the charges of "rightist-nationalist deviation" against him.

Rise to power

In June 1956, violent worker protests broke out in

In June 1956, violent worker protests broke out in Poznań

Poznań () is a city on the River Warta in west-central Poland, within the Greater Poland region. The city is an important cultural and business centre, and one of Poland's most populous regions with many regional customs such as Saint Joh ...

. The worker riots were harshly suppressed and dozens of workers were killed. However, the Party leadership, which now included many reform-minded officials, recognized to some degree the validity of the protest participants' demands and took steps to placate the workers.

The reformers in the Party wanted a political rehabilitation

Political rehabilitation is the process by which a disgraced member of a political party or a government is restored to public respectability and thus political acceptability. The term is usually applied to leaders or other prominent individuals ...

of Gomułka and his return to the Party leadership. Gomułka insisted that he be given real power to implement further reforms. He wanted a replacement of some of the Party leaders, including the pro-Soviet Minister of Defense Konstantin Rokossovsky

Konstantin Konstantinovich (Xaverevich) Rokossovsky ( Russian: Константин Константинович Рокоссовский; pl, Konstanty Rokossowski; 21 December 1896 – 3 August 1968) was a Soviet and Polish officer who bec ...

.

The Soviet leadership viewed events in Poland with alarm. Simultaneously with Soviet troop movements deep into Poland, a high-level Soviet delegation flew to Warsaw. It was led by Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev s ...

and included Anastas Mikoyan

Anastas Ivanovich Mikoyan (; russian: Анаста́с Ива́нович Микоя́н; hy, Անաստաս Հովհաննեսի Միկոյան; 25 November 1895 – 21 October 1978) was an Armenian Communist revolutionary, Old Bolshevik an ...

, Nikolai Bulganin

Nikolai Alexandrovich Bulganin (russian: Никола́й Алекса́ндрович Булга́нин; – 24 February 1975) was a Soviet politician who served as Minister of Defense (1953–1955) and Premier of the Soviet Union (1955–19 ...

, Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Mikhaylovich Molotov. ; (;. 9 March Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O._S._25_February.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O. S. 25 February">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dat ...

, Lazar Kaganovich

Lazar Moiseyevich Kaganovich, also Kahanovich (russian: Ла́зарь Моисе́евич Кагано́вич, Lázar' Moiséyevich Kaganóvich; – 25 July 1991), was a Soviet politician and administrator, and one of the main associates of ...

, Ivan Konev

Ivan Stepanovich Konev ( rus, link=no, Ива́н Степа́нович Ко́нев, p=ɪˈvan sʲtʲɪˈpanəvʲɪtɕ ˈkonʲɪf; – 21 May 1973) was a Soviet general and Marshal of the Soviet Union who led Red Army forces on the ...

and others. Ochab and Gomułka made it clear that Polish forces would resist if Soviet troops advanced, but reassured the Soviets that the reforms were internal matters and that Poland had no intention of abandoning the communist bloc or its treaties with the Soviet Union. The Soviets yielded.

Following the wishes of the majority of the Politburo

A politburo () or political bureau is the executive committee for communist parties. It is present in most former and existing communist states.

Names

The term "politburo" in English comes from the Russian ''Politbyuro'' (), itself a contracti ...

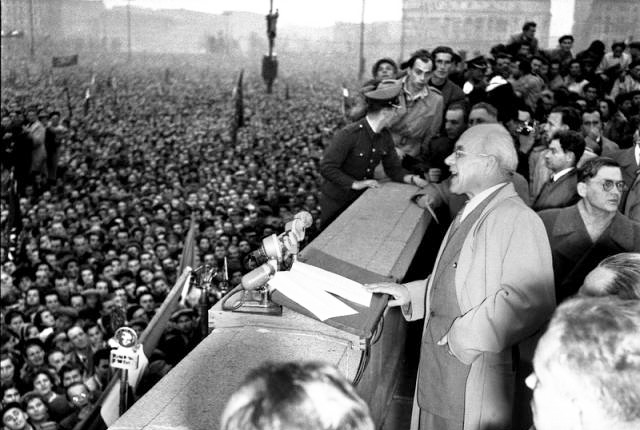

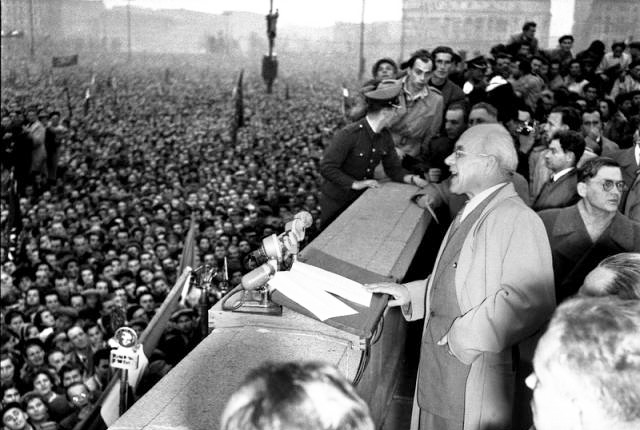

members, First Secretary Ochab conceded and on 20 October the Central Committee

Central committee is the common designation of a standing administrative body of communist parties, analogous to a board of directors, of both ruling and nonruling parties of former and existing socialist states. In such party organizations, the ...

brought Gomułka and several associates into the Politburo, removed others, and elected Gomułka as the first secretary of the Party. Gomułka, the former prisoner of the Stalinists, enjoyed wide popular support across the country, expressed by the participants of a massive street demonstration in Warsaw on 24 October. Seeing that Gomułka was popular with the Polish people, and given his insistence that he wanted to maintain the alliance with the Soviet Union and the presence of the Red Army in Poland

The Northern Group of Forces (; ) was the military formation of the Soviet Army stationed in Poland from the end of Second World War in 1945 until 1993 when they were withdrawn in the aftermath of the fall of the Soviet Union. Although officially ...

, Khrushchev decided that Gomułka was a leader that Moscow could live with.

Leadership of the Polish People's Republic

Relations with other Eastern Bloc countries

A major factor that influenced Gomułka was the Oder-Neisse line issue. West Germany refused to recognize the Oder-Neisse line and Gomułka realized the fundamental instability of Poland's unilaterally imposed western border.Granville, Johanna "Reactions to the Events of 1956: New Findings from the Budapest and Warsaw Archives" pages 261-290 from ''Journal of Contemporary History'', Volume 38, Issue #2, April 2003 pp. 284–85. He felt threatened by the revanchist statements put out by the Adenauer government and believed that the alliance with the Soviet Union was the only thing stopping the threat of a future German invasion.Granville, Johanna "From the Archives of Warsaw and Budapest: A Comparison of the Events of 1956" pp. 521–63 from ''East European Politics and Societies'', Volume 16, Issue #2, April 2002 pp. 540–41 The new Party leader told the 8th Plenum of the PZPR on 19 October 1956 that: "Poland needs friendship with the Soviet Union more than the Soviet Union needs friendship with Poland... Without the Soviet Union we cannot maintain our borders with the West".Granville, Johanna "From the Archives of Warsaw and Budapest: A Comparison of the Events of 1956" pp. 521–63 from ''East European Politics and Societies'', Volume 16, Issue #2, April 2002 p. 541 The treaty with West Germany was negotiated and signed in December 1970. The German side recognized the post-World War II borders, which established a foundation for future peace, stability and cooperation inCentral Europe

Central Europe is an area of Europe between Western Europe and Eastern Europe, based on a common historical, social and cultural identity. The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) between Catholicism and Protestantism significantly shaped the a ...

.

During the events of the Prague Spring

The Prague Spring ( cs, Pražské jaro, sk, Pražská jar) was a period of political liberalization and mass protest in

the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic. It began on 5 January 1968, when reformist Alexander Dubček was elected First ...

, Gomułka was one of the key leaders of the Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Pact (WP) or Treaty of Warsaw, formally the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance, was a collective defense treaty signed in Warsaw, Poland, between the Soviet Union and seven other Eastern Bloc socialist republi ...

and supported Poland's participation in the invasion of Czechoslovakia in August 1968.

Domestic policies

In 1967–68 Gomułka allowed outbursts of "anti-Zionist" political propaganda, which developed initially as a result of the Soviet bloc's frustration with the outcome of the Arab-IsraeliSix-Day War

The Six-Day War (, ; ar, النكسة, , or ) or June War, also known as the 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab states (primarily Egypt, Syria, and Jordan) from 5 to 10 ...

. It turned out to be a thinly veiled antisemitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Ant ...

campaign and purge of the army, pursued primarily by others in the Party, but utilized by Gomułka to keep himself in power by shifting the attention of the populace from the stagnating economy and mismanagement. The result was the emigration of the majority of the remaining Polish citizens of Jewish origin

The history of the Jews in Poland dates back at least 1,000 years. For centuries, Poland was home to the largest and most significant Ashkenazi Jewish community in the world. Poland was a principal center of Jewish culture, because of the lo ...

. At that time he was also responsible for persecuting protesting students and toughening censorship of the media.

Resignation and retirement

In December 1970, economic difficulties led to price rises and subsequent

In December 1970, economic difficulties led to price rises and subsequent protests

A protest (also called a demonstration, remonstration or remonstrance) is a public expression of objection, disapproval or dissent towards an idea or action, typically a political one.

Protests can be thought of as acts of coopera ...

. Gomułka along with his right-hand man Zenon Kliszko

Zenon Kliszko (Łódź, December 8, 1908 – September 4, 1989, Warsaw), was a politician in the Polish People's Republic, considered the man of Polish United Workers' Party (PZPR) leader Władysław Gomułka.

Kliszko graduated from Warsaw Univ ...

ordered the regular Army under General

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". O ...

Bolesław Chocha, to shoot striking workers with automatic weapons

An automatic firearm is an auto-loading firearm that continuously chambers and fires rounds when the trigger mechanism is actuated. The action of an automatic firearm is capable of harvesting the excess energy released from a previous dischar ...

in Gdańsk

Gdańsk ( , also ; ; csb, Gduńsk;Stefan Ramułt, ''Słownik języka pomorskiego, czyli kaszubskiego'', Kraków 1893, Gdańsk 2003, ISBN 83-87408-64-6. , Johann Georg Theodor Grässe, ''Orbis latinus oder Verzeichniss der lateinischen Benen ...

and Gdynia

Gdynia ( ; ; german: Gdingen (currently), (1939–1945); csb, Gdiniô, , , ) is a city in northern Poland and a seaport on the Baltic Sea coast. With a population of 243,918, it is the 12th-largest city in Poland and the second-largest in th ...

. Over 41 shipyard workers of the Baltic coast were killed in the ensuing police-state violence, while well over a thousand people were wounded. The events forced Gomułka's resignation and retirement. In a generational replacement of the ruling elite, Edward Gierek

Edward Gierek (; 6 January 1913 – 29 July 2001) was a Polish Communist politician and ''de facto'' leader of Poland between 1970 and 1980. Gierek replaced Władysław Gomułka as First Secretary of the ruling Polish United Workers' Party (P ...

took over the Party leadership and tensions eased.

Gomułka's negative image in communist propaganda after his removal was gradually modified and some of his constructive contributions were recognized. He is seen as an honest and austere believer in the socialist system

A socialist state, socialist republic, or socialist country, sometimes referred to as a workers' state or workers' republic, is a sovereign state constitutionally dedicated to the establishment of socialism. The term ''communist state'' is ofte ...

, who, unable to resolve Poland's formidable difficulties and satisfy mutually contradictory demands, grew more rigid and despotic later in his career. A heavy smoker, he died in 1982 at the age of 77 of lung cancer. Gomułka's memoirs were not published until 1994, long after his death, and five years after the collapse of the communist regime which he served and led.

The American journalist John Gunther

John Gunther (August 30, 1901 – May 29, 1970) was an American journalist and writer.

His success came primarily by a series of popular sociopolitical works, known as the "Inside" books (1936–1972), including the best-selling ''Insid ...

described Gomułka in 1961 as being "professorial in manner, aloof, and angular, with a peculiar spry pepperiness".

Gomułka was buried at Powązki Military Cemetery

Powązki Military Cemetery (; pl, Cmentarz Wojskowy na Powązkach) is an old military cemetery located in the Żoliborz district, western part of Warsaw, Poland. The cemetery is often confused with the older Powązki Cemetery, known colloquial ...

in Warsaw.

Decorations and awards

*: **Order of Polonia Restituta

The Order of Polonia Restituta ( pl, Order Odrodzenia Polski, en, Order of Restored Poland) is a Polish state order established 4 February 1921. It is conferred on both military and civilians as well as on foreigners for outstanding achievemen ...

**Legion of Honour

The National Order of the Legion of Honour (french: Ordre national de la Légion d'honneur), formerly the Royal Order of the Legion of Honour ('), is the highest French order of merit, both military and civil. Established in 1802 by Napoleo ...

(France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

)

**Order of Merit of the Italian Republic

The Order of Merit of the Italian Republic ( it, Ordine al Merito della Repubblica Italiana) is the senior Italian order of merit. It was established in 1951 by the second President of the Italian Republic, Luigi Einaudi.

The highest-rankin ...

(Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

)

**

Order of Lenin

The Order of Lenin (russian: Орден Ленина, Orden Lenina, ), named after the leader of the Russian October Revolution, was established by the Central Executive Committee on April 6, 1930. The order was the highest civilian decoration ...

(Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

)

**

Jubilee Medal "In Commemoration of the 100th Anniversary of the Birth of Vladimir Ilyich Lenin"

The Jubilee Medal "In Commemoration of the 100th Anniversary of the Birth of Vladimir Ilyich Lenin" (russian: link=no, Юбилейная медаль В ознаменование 100-летия со дня рождения Владимира И ...

(Soviet Union)

See also

* History of Poland (1945–89)References

External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Gomulka, Wladyslaw 1905 births 1982 deaths People from Krosno People from the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria Communist Party of Poland politicians Communist Party of the Soviet Union members Polish Workers' Party politicians Members of the Politburo of the Polish United Workers' Party Members of the State National Council Members of the Polish Sejm 1947–1952 Members of the Polish Sejm 1957–1961 Members of the Polish Sejm 1961–1965 Members of the Polish Sejm 1965–1969 Members of the Polish Sejm 1969–1972 Polish atheists Communist rulers Collaborators with the Soviet Union Antisemitism in Poland Anti-intellectualism Anti-Catholicism in Poland International Lenin School alumni Recipients of the Order of the Cross of Grunwald, 1st class Recipients of the Order of the Builders of People's Poland Grand Crosses of the Order of Polonia Restituta Recipients of the Order of Polonia Restituta (1944–1989) Recipients of the Order of the Banner of Work Grand Officiers of the Légion d'honneur Knights Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic Recipients of the Order of Lenin People of the Cold War