Vladimir Purishkevich on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Vladimir Mitrofanovich Purishkevich ( rus, Влади́мир Митрофа́нович Пуришке́вич, p=pʊrʲɪˈʂkʲevʲɪt͡ɕ; , Kishinev – 1 February 1920,

Vladimir Mitrofanovich Purishkevich ( rus, Влади́мир Митрофа́нович Пуришке́вич, p=pʊrʲɪˈʂkʲevʲɪt͡ɕ; , Kishinev – 1 February 1920,

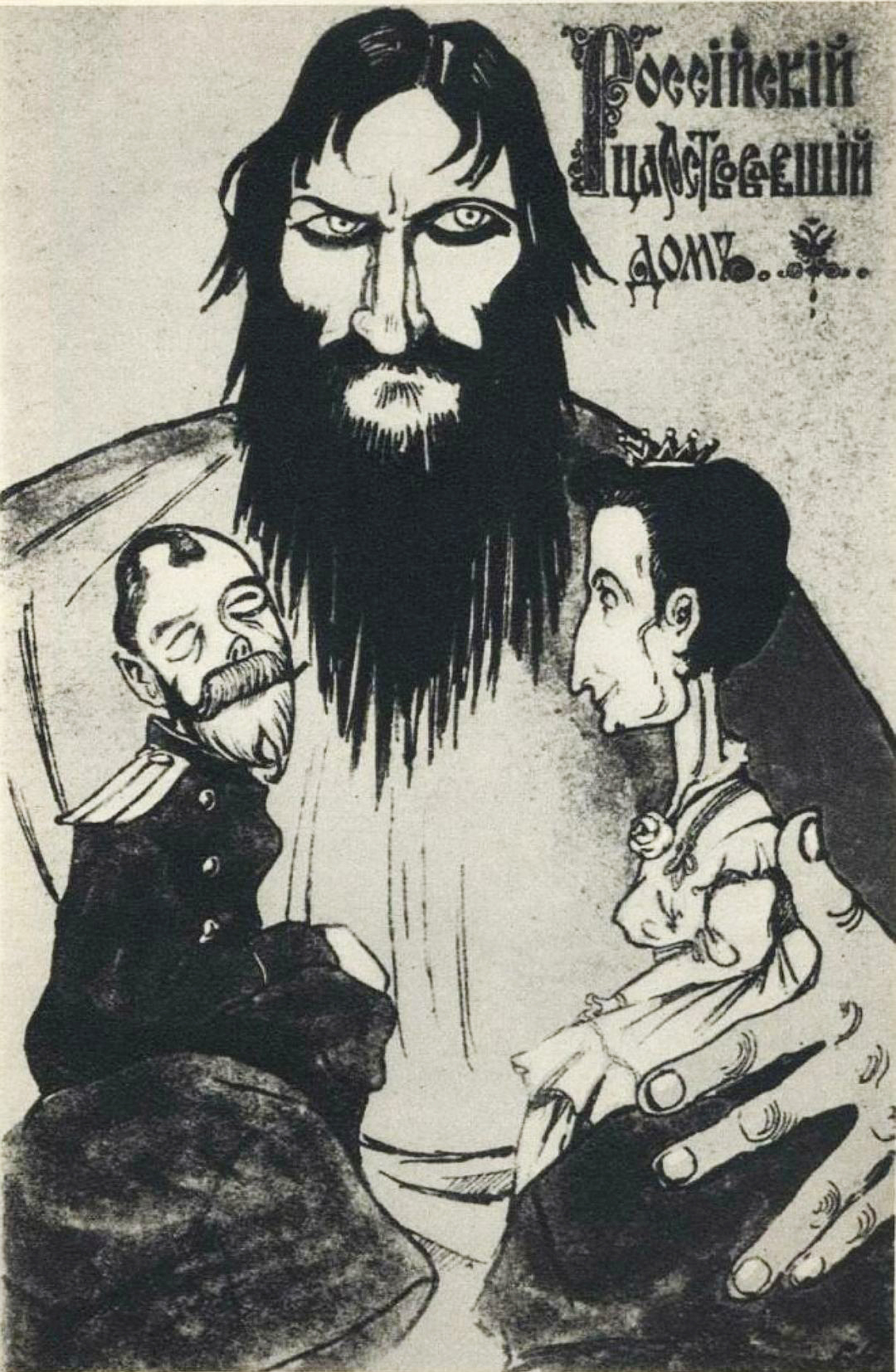

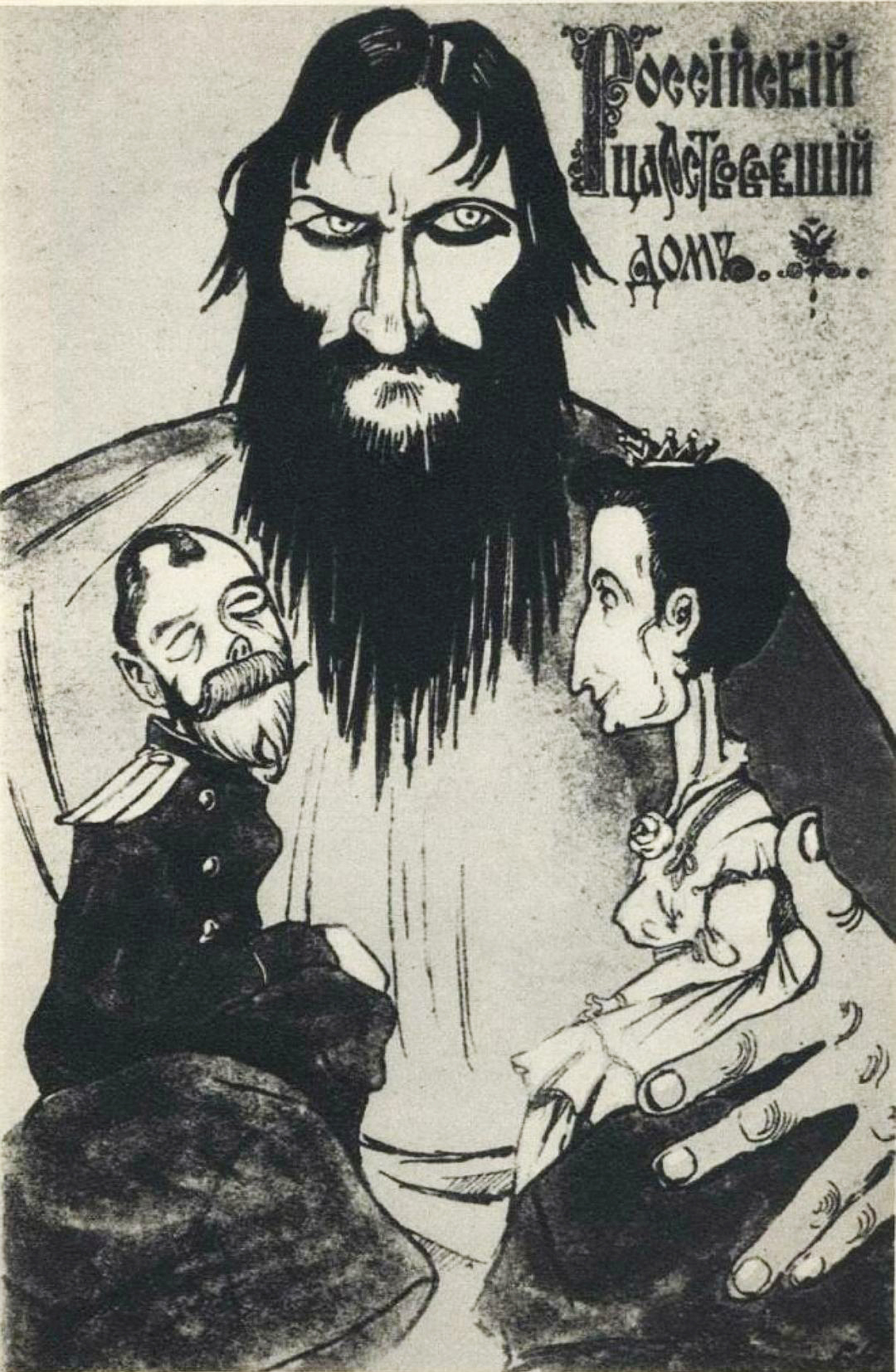

Purishkevich stated that Rasputin's influence over the Tsarina had made him a threat to the empire: "an obscure

Purishkevich stated that Rasputin's influence over the Tsarina had made him a threat to the empire: "an obscure

They had planned to burn Rasputin's possessions. Sukhotin put on Rasputin's fur coat, rubber boots, and gloves. He left with Dmitri and Dr. Lazovert in Purishkevich's car, which suggests that Rasputin had left the palace alive. Because Purishkevich's wife refused to burn the fur coat and the boots in her small fireplace in the ambulance train, the conspirators went back to the palace with the larger items.

Yusupov and Dmitri were placed under house arrest in the Sergei Palace. The Tsarina had refused to meet them but said that they could explain to her what had happened in a letter. Purishkevich assisted them and left the city to the Romanian front at ten in the evening. Because of his popularity, Purishkevich was neither punished nor banned.

They had planned to burn Rasputin's possessions. Sukhotin put on Rasputin's fur coat, rubber boots, and gloves. He left with Dmitri and Dr. Lazovert in Purishkevich's car, which suggests that Rasputin had left the palace alive. Because Purishkevich's wife refused to burn the fur coat and the boots in her small fireplace in the ambulance train, the conspirators went back to the palace with the larger items.

Yusupov and Dmitri were placed under house arrest in the Sergei Palace. The Tsarina had refused to meet them but said that they could explain to her what had happened in a letter. Purishkevich assisted them and left the city to the Romanian front at ten in the evening. Because of his popularity, Purishkevich was neither punished nor banned.

During the

During the

After his release, he moved to

After his release, he moved to

Vladimir Mitrofanovich Purishkevich ( rus, Влади́мир Митрофа́нович Пуришке́вич, p=pʊrʲɪˈʂkʲevʲɪt͡ɕ; , Kishinev – 1 February 1920,

Vladimir Mitrofanovich Purishkevich ( rus, Влади́мир Митрофа́нович Пуришке́вич, p=pʊrʲɪˈʂkʲevʲɪt͡ɕ; , Kishinev – 1 February 1920, Novorossiysk

Novorossiysk ( rus, Новоросси́йск, p=nəvərɐˈsʲijsk; ady, ЦIэмэз, translit=Chəməz, p=t͡sʼɜmɜz) is a city in Krasnodar Krai, Russia. It is one of the largest ports on the Black Sea. It is one of the few cities hono ...

, Russia) was a far-right

Far-right politics, also referred to as the extreme right or right-wing extremism, are political beliefs and actions further to the right of the left–right political spectrum than the standard political right, particularly in terms of being ...

politician in Imperial Russia

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the List of Russian monarchs, Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended th ...

, noted for his monarchist

Monarchism is the advocacy of the system of monarchy or monarchical rule. A monarchist is an individual who supports this form of government independently of any specific monarch, whereas one who supports a particular monarch is a royalist. ...

, ultra-nationalist

Ultranationalism or extreme nationalism is an extreme form of nationalism in which a country asserts or maintains detrimental hegemony, supremacy, or other forms of control over other nations (usually through violent coercion) to pursue its sp ...

, antisemitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

and anticommunist

Anti-communism is political and ideological opposition to communism. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in the Russian Empire, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, when the United States and the ...

views. Because of his restless behaviour, he was regarded as a loose cannon. At the end of 1916, he participated in the killing of Grigori Rasputin

Grigori Yefimovich Rasputin (; rus, links=no, Григорий Ефимович Распутин ; – ) was a Russian mystic and self-proclaimed holy man who befriended the family of Nicholas II, the last Emperor of Russia, thus g ...

.

Early career

Born as the son of a poor nobleman inBessarabia

Bessarabia (; Gagauz: ''Besarabiya''; Romanian: ''Basarabia''; Ukrainian: ''Бессара́бія'') is a historical region in Eastern Europe, bounded by the Dniester river on the east and the Prut river on the west. About two thirds of Be ...

, now Moldova

Moldova ( , ; ), officially the Republic of Moldova ( ro, Republica Moldova), is a Landlocked country, landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by Romania to the west and Ukraine to the north, east, and south. The List of states ...

, Purishkevich graduated from Novorossiysk

Novorossiysk ( rus, Новоросси́йск, p=nəvərɐˈsʲijsk; ady, ЦIэмэз, translit=Chəməz, p=t͡sʼɜmɜz) is a city in Krasnodar Krai, Russia. It is one of the largest ports on the Black Sea. It is one of the few cities hono ...

University with a degree in classical philology

Classics or classical studies is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, classics traditionally refers to the study of Classical Greek and Roman literature and their related original languages, Ancient Greek and Latin. Classics ...

. Around 1900, he moved to Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

. He became a member of the Russian Assembly

The Russian Assembly (russian: link=no, Русское собрание) was a Russian loyalist, right-wing, monarchist political group (party). It was founded in Saint Petersburg in October−November 1900, and dismissed in 1917. It was led by Pr ...

group and was appointed under Vyacheslav von Plehve

Vyacheslav Konstantinovich von Plehve ( rus, Вячесла́в (Wenzel (Славик)) из Плевны Константи́нович фон Пле́ве, p=vʲɪtɕɪˈslaf fɐn ˈplʲevʲɪ; – ) served as a director of Imperial Russ ...

.

During the Russian Revolution of 1905

The Russian Revolution of 1905,. also known as the First Russian Revolution,. occurred on 22 January 1905, and was a wave of mass political and social unrest that spread through vast areas of the Russian Empire. The mass unrest was directed again ...

, he helped organise the Black Hundreds

The Black Hundred (russian: Чёрная сотня, translit=Chornaya sotnya), also known as the black-hundredists (russian: черносотенцы; chernosotentsy), was a reactionary, monarchist and ultra-nationalist movement in Russia in t ...

as a militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

to aid the police in the fight against left-wing

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in soci ...

extremists

Extremism is "the quality or state of being extreme" or "the advocacy of extreme measures or views". The term is primarily used in a political or religious sense to refer to an ideology that is considered (by the speaker or by some implied shar ...

and to restore order. After the October Manifesto

The October Manifesto (russian: Октябрьский манифест, Манифест 17 октября), officially "The Manifesto on the Improvement of the State Order" (), is a document that served as a precursor to the Russian Empire's fi ...

, he was one of the founders of the Union of the Russian People

The Union of the Russian People (URP) (russian: Союз русского народа, translit=Soyuz russkogo naroda; СРН/SRN) is a loyalist far-right nationalist political party, the most important among Black-Hundredist monarchist politi ...

and its deputy chairman. Following a disagreement with Alexander Dubrovin

Alexander Ivanovich Dubrovin (russian: Алекса́ндр Ива́нович Дубро́вин) (1855, Kungur – unknown) was a Russian Empire right wing politician, a leader of the Union of the Russian People (URP).

Biography

A trained do ...

on the influence of the State Duma, he founded his own organisation, the Union of the Archangel Michael, in 1908.

The popular Purishkevich, described by Vladimir Kokovtsov

Count Vladimir Nikolayevich Kokovtsov (russian: Влади́мир Никола́евич Коко́вцов; – 29 January 1943) was a Russian politician who served as the Prime Minister of Russia from 1911 to 1914, during the reign of Emper ...

as a charming, unstable man who could not stay a single minute in one place, was elected as a deputy of the second, third and fourth Imperial Duma

The State Duma, also known as the Imperial Duma, was the lower house of the Governing Senate in the Russian Empire, while the upper house was the State Council. It held its meetings in the Taurida Palace in St. Petersburg. It convened four times ...

s for the Bessarabian and Kursk

Kursk ( rus, Курск, p=ˈkursk) is a city and the administrative center of Kursk Oblast, Russia, located at the confluence of the Kur, Tuskar, and Seym rivers. The area around Kursk was the site of a turning point in the Soviet–German stru ...

province. He gained fame for his flamboyant speeches and scandalous behaviour such as speaking on the 1st of May

Events Pre-1600

* 305 – Diocletian and Maximian retire from the office of Roman emperor.

* 880 – The Nea Ekklesia is inaugurated in Constantinople, setting the model for all later cross-in-square Orthodox churches.

* 1169 &ndas ...

with a red carnation

''Dianthus caryophyllus'' (), commonly known as the carnation or clove pink, is a species of ''Dianthus''. It is likely native to the Mediterranean region but its exact range is unknown due to extensive cultivation for the last 2,000 years.Med ...

in his fly

Flies are insects of the Order (biology), order Diptera, the name being derived from the Ancient Greek, Greek δι- ''di-'' "two", and πτερόν ''pteron'' "wing". Insects of this order use only a single pair of wings to fly, the hindwing ...

. He was a hardline supporter of sacerdotal Sacerdotalism (from Latin ''sacerdos'', priest, literally one who presents sacred offerings, ''sacer'', sacred, and ''dare'', to give) is the belief in some Christian churches that priests are meant to be mediators between God and humankind. The und ...

autocracy

Autocracy is a system of government in which absolute power over a state is concentrated in the hands of one person, whose decisions are subject neither to external legal restraints nor to regularized mechanisms of popular control (except perh ...

, and of Russification

Russification (russian: русификация, rusifikatsiya), or Russianization, is a form of cultural assimilation in which non-Russians, whether involuntarily or voluntarily, give up their culture and language in favor of the Russian cultur ...

to create unity. Purishkevich's hostility to the Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

was caused by his perception of them to be the "vanguard of the revolutionary movement". He wanted them to be deported to Kolyma

Kolyma (russian: Колыма́, ) is a region located in the Russian Far East. It is bounded to the north by the East Siberian Sea and the Arctic Ocean, and by the Sea of Okhotsk to the south. The region gets its name from the Kolyma River an ...

. He believed that the " Kadets, socialists, the intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a status class composed of the university-educated people of a society who engage in the complex mental labours by which they critique, shape, and lead in the politics, policies, and culture of their society; as such, the in ...

, the press and councils of university professors" were all under the control of Jews.

During the war, Purishkevich became critical of the performance of the government and the role of Alexandra

Alexandra () is the feminine form of the given name Alexander (, ). Etymologically, the name is a compound of the Greek verb (; meaning 'to defend') and (; GEN , ; meaning 'man'). Thus it may be roughly translated as "defender of man" or "prot ...

and Rasputin but not of the Tsar.

Criticism of Rasputin

On 3 November 1916, Purishkevich went toMogilev

Mogilev (russian: Могилёв, Mogilyov, ; yi, מאָלעוו, Molev, ) or Mahilyow ( be, Магілёў, Mahilioŭ, ) is a city in eastern Belarus, on the Dnieper River, about from the border with Russia's Smolensk Oblast and from the bor ...

and talked with Tsar Nicolas II on Rasputin. On 19 November, Purishkevich gave a speech in the Duma and coined the phrase "ministerial leapfrog" to describe the seemingly continuous government reshuffles.

He compared Rasputin with the False Dmitri. The monarchy was becoming discredited:

Purishkevich stated that Rasputin's influence over the Tsarina had made him a threat to the empire: "an obscure

Purishkevich stated that Rasputin's influence over the Tsarina had made him a threat to the empire: "an obscure moujik

The term ''serf'', in the sense of an unfree peasant of tsarist Russia, is the usual English-language translation of () which meant an unfree person who, unlike a slave, historically could be sold only with the land to which they were "attach ...

shall govern Russia no longer!" "While Rasputin is alive, we cannot win".

Killing of Rasputin

PrinceFelix Yusupov

Prince Felix Felixovich Yusupov, Count Sumarokov-Elston (russian: Князь Фе́ликс Фе́ликсович Юсу́пов, Граф Сумаро́ков-Эльстон, Knyaz' Féliks Féliksovich Yusúpov, Graf Sumarókov-El'ston; – ...

was impressed by the speech. He visited Purishkevich, who quickly agreed to participate in the killing of Rasputin. Also, Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich joined the conspiracy. Purishkevich talked to Samuel Hoare, the head of the British Secret Intelligence Service in Petrograd

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

.

A wealthy person, Purishkevich organised a medical aid that went up and down to the Eastern Front to deliver wounded soldiers to the hospitals in Tsarskoye Selo

Tsarskoye Selo ( rus, Ца́рское Село́, p=ˈtsarskəɪ sʲɪˈlo, a=Ru_Tsarskoye_Selo.ogg, "Tsar's Village") was the town containing a former residence of the Russian imperial family and visiting nobility, located south from the cen ...

.

On the evening of 16 December 1916, the conspirators gathered in the Moika Palace

The Palace of the Yusupovs on the Moika (russian: Дворец Юсуповых на Мойке), known as the Moika Palace or Yusupov Palace, is a former residence of the Russian noble House of Yusupov in St. Petersburg, Russia, now a museum. ...

and eventually killed Rasputin.

A curious policeman on duty on the other side of the Moika

The Moyka (russian: Мо́йка /MOY-ka/, also latinised as Moika) is a secondary, in comparison with the Neva River in Saint Petersburg that encircles the central portion of the city, effectively making it an island or a group of islands ...

had heard the shots, rang at the door, and was sent away. Half an hour later, another policeman arrived, and Purishkevich invited him into the palace. Purishkevich told him that he had shot Rasputin and asked him to keep it quiet for the sake of the Tsar.

They had planned to burn Rasputin's possessions. Sukhotin put on Rasputin's fur coat, rubber boots, and gloves. He left with Dmitri and Dr. Lazovert in Purishkevich's car, which suggests that Rasputin had left the palace alive. Because Purishkevich's wife refused to burn the fur coat and the boots in her small fireplace in the ambulance train, the conspirators went back to the palace with the larger items.

Yusupov and Dmitri were placed under house arrest in the Sergei Palace. The Tsarina had refused to meet them but said that they could explain to her what had happened in a letter. Purishkevich assisted them and left the city to the Romanian front at ten in the evening. Because of his popularity, Purishkevich was neither punished nor banned.

They had planned to burn Rasputin's possessions. Sukhotin put on Rasputin's fur coat, rubber boots, and gloves. He left with Dmitri and Dr. Lazovert in Purishkevich's car, which suggests that Rasputin had left the palace alive. Because Purishkevich's wife refused to burn the fur coat and the boots in her small fireplace in the ambulance train, the conspirators went back to the palace with the larger items.

Yusupov and Dmitri were placed under house arrest in the Sergei Palace. The Tsarina had refused to meet them but said that they could explain to her what had happened in a letter. Purishkevich assisted them and left the city to the Romanian front at ten in the evening. Because of his popularity, Purishkevich was neither punished nor banned.

Revolutionary Russia

February Revolution

The February Revolution ( rus, Февра́льская револю́ция, r=Fevral'skaya revolyutsiya, p=fʲɪvˈralʲskəjə rʲɪvɐˈlʲutsɨjə), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and somet ...

in 1917, many right-wingers were arrested but Purishkevich was tolerated by the government and so was "virtually the only former national Black Hundred leader to maintain an active political life in Russia after the Tsar's downfall". However, the revolution meant that Purishkevich initially had to moderate his politics. He called for the abolition of the Soviets

Soviet people ( rus, сове́тский наро́д, r=sovyétsky naród), or citizens of the USSR ( rus, гра́ждане СССР, grázhdanye SSSR), was an umbrella demonym for the population of the Soviet Union.

Nationality policy in th ...

, who were, in turn, calling for the abolition of the Duma.

In August 1917, he wanted a military dictatorship; he was arrested over the Kornilov Affair but was released. Following the failure of the putsch, he collaborated with Fyodor Viktorovich Vinberg

Fyodor Viktorovich Vinberg (russian: Фёдор Викторович Винберг; – 14 February 1927) was a right-wing Russian military officer, publisher and journalist.

Early life

Born in Kiev in the family of a general with German ba ...

in forming an underground monarchist organisation. During the October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key moment ...

, he organized the "Committee for the Motherland's Salvation". He was joined by a number of officers, military cadets, and others.

At the time, Purishkevich was living in the Hotel Russia at Moika

The Moyka (russian: Мо́йка /MOY-ka/, also latinised as Moika) is a secondary, in comparison with the Neva River in Saint Petersburg that encircles the central portion of the city, effectively making it an island or a group of islands ...

60. He had a false passport under the surname "Yevreinov". On 18 November 1917, Purishkevich was arrested by the Red Guards

Red Guards () were a mass student-led paramilitary social movement mobilized and guided by Chairman Mao Zedong in 1966 through 1967, during the first phase of the Cultural Revolution, which he had instituted.Teiwes According to a Red Guard lead ...

for his participation in a counterrevolutionary conspiracy after the discovery of a letter sent by him to General Aleksei Maksimovich Kaledin in which he urged the Cossack leader to come and restore order in Petrograd

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

.Andrew Kalpaschnikoff, A Prisoner of Trotsky's, 1920 He became the first person to be tried in the Smolny Institute

The Smolny Institute (russian: Смольный институт, ''Smol'niy institut'') is a Palladian edifice in Saint Petersburg that has played a major part in the history of Russia.

History

The building was commissioned from Giacomo Quar ...

by the first Revolutionary Tribunal. He was condemned to eleven months of 'public work' and four years of imprisonment with obligatory community service and won the admiration of his fellow prisoners in the Fortress of St Peter and St Paul by his courageous bearing.Irene Zohrab, "The Liberals among the forces of the Revolution: from the unpublished papers of Harold W. Williams". New Zealand Slavonic Journal, 20, (1986), 63-64. He was given an amnesty on May 1 after the mediation of Felix Dzerzhinsky

Felix Edmundovich Dzerzhinsky ( pl, Feliks Dzierżyński ; russian: Фе́ликс Эдму́ндович Дзержи́нский; – 20 July 1926), nicknamed "Iron Felix", was a Bolshevik revolutionary and official, born into Poland, Polish n ...

and Nikolay Krestinsky

Nikolay Nikolayevich Krestinsky (russian: Никола́й Никола́евич Крести́нский; 13 October 1883 – 15 March 1938) was a Russian Bolshevik revolutionary and Soviet politician who served as the Responsible Sec ...

, as he refrained from any political activity. In jail, he had written a poem describing the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (also known as the Treaty of Brest in Russia) was a separate peace, separate peace treaty signed on 3 March 1918 between Russian SFSR, Russia and the Central Powers (German Empire, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Kingdom of ...

as 'The Trotsky Peace'.

White Russia

After his release, he moved to

After his release, he moved to White Army

The White Army (russian: Белая армия, Belaya armiya) or White Guard (russian: Бѣлая гвардія/Белая гвардия, Belaya gvardiya, label=none), also referred to as the Whites or White Guardsmen (russian: Бѣлогв� ...

controlled Southern Russia

Southern Russia or the South of Russia (russian: Юг России, ''Yug Rossii'') is a colloquial term for the southernmost geographic portion of European Russia generally covering the Southern Federal District and the North Caucasian Federal ...

. There, during the Russian Civil War

, date = October Revolution, 7 November 1917 – Yakut revolt, 16 June 1923{{Efn, The main phase ended on 25 October 1922. Revolt against the Bolsheviks continued Basmachi movement, in Central Asia and Tungus Republic, the Far East th ...

he published the monarchist journal ''Blagovest'' and returned openly to his traditional political stance of support for the monarchy, a unified Russia, and opposition to the Jews. In some of the towns occupied by the Volunteer Army, he gave lectures in which he denounced the British policy towards Russia. In 1918, he formed a new political party, the People's State Party, and called for an "open fight against Jewry"; the party collapsed after his death.

Vladimir Purishkevich died from typhus

Typhus, also known as typhus fever, is a group of infectious diseases that include epidemic typhus, scrub typhus, and murine typhus. Common symptoms include fever, headache, and a rash. Typically these begin one to two weeks after exposure.

...

that raged Novorossiysk

Novorossiysk ( rus, Новоросси́йск, p=nəvərɐˈsʲijsk; ady, ЦIэмэз, translit=Chəməz, p=t͡sʼɜmɜz) is a city in Krasnodar Krai, Russia. It is one of the largest ports on the Black Sea. It is one of the few cities hono ...

in 1920, just before the final evacuation of Denikin

Anton Ivanovich Denikin (russian: Анто́н Ива́нович Дени́кин, link= ; 16 December Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S._4_December.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New St ...

's Army.

Reputation

In 1925, Soviet writer Liubosh would describe Purishkevich as the 'first'fascist

Fascism is a far-right, Authoritarianism, authoritarian, ultranationalism, ultra-nationalist political Political ideology, ideology and Political movement, movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and pol ...

. He was subsequently referred to as a "leader of early Russian fascism" by Semyon Reznik Semyon Efimovich Reznik (Russian: Семён Ефимович Резник) (born 13 June 1938, in Moscow) is a Russian writer, journalist, man of letters and historian, noted in particular for his study of the blood libel and the resurgence of Neo ...

, who also claimed that Purishkevich participated in numerous pogrom

A pogrom () is a violent riot incited with the aim of massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe 19th- and 20th-century attacks on Jews in the Russia ...

s and was a significant proponent of the blood libel against Jews

Blood libel or ritual murder libel (also blood accusation) is an antisemitic canardTurvey, Brent E. ''Criminal Profiling: An Introduction to Behavioral Evidence Analysis'', Academic Press, 2008, p. 3. "Blood libel: An accusation of ritual mur ...

.

References

Sources

* Vladimir Pourichkevitch (1924) ''Comment j'ai tué Raspoutine. Pages de Journal''. J. Povolozky & Cie. Paris. Translated and published as ''The murder of Rasputin'' (1985) Ardis. * 1870 births 1920 deaths Politicians from Chișinău People from Kishinyovsky Uyezd Members of the Union of the Russian People Members of the Russian Assembly Members of the 2nd State Duma of the Russian Empire Members of the 3rd State Duma of the Russian Empire Members of the 4th State Duma of the Russian Empire Blood libel Russian conspiracy theorists Russian anti-communists Antisemitism in Russia Russian murderers Kishinev pogrom Russian people of Polish descent{{cite web , url=https://glasul.info/2017/06/02/cautarea-lui-vladimir-purischevici-partea-1-sutele-negre-ante-primul-razboi-mondial/ , title=În căutarea lui Vladimir Purișchevici Partea 1: Sutele Negre (Ante-Primul Război Mondial) , date=2 June 2017 Russian people of Moldovan descent