Victoria Falls Conference (1975) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Victoria Falls Conference took place on 26 August 1975 aboard a

The Victoria Falls Conference took place on 26 August 1975 aboard a

After the Wind of Change of the early 1960s, the British government under

After the Wind of Change of the early 1960s, the British government under

The conference started on the morning of 26 August as planned. The six Rhodesian delegates took their places first, then around 40 nationalists entered and crowded around Muzorewa on the opposite side of the cramped railway carriage. Vorster and Kaunda arrived and sat on the Rhodesian side, where there was more space, and each spoke in turn, giving their blessing to the negotiations. Muzorewa then opened the proceedings at Smith's invitation. Speaking assertively, the bishop gave three concessions which would have to be given by the Rhodesian side for talks to begin: first,

The conference started on the morning of 26 August as planned. The six Rhodesian delegates took their places first, then around 40 nationalists entered and crowded around Muzorewa on the opposite side of the cramped railway carriage. Vorster and Kaunda arrived and sat on the Rhodesian side, where there was more space, and each spoke in turn, giving their blessing to the negotiations. Muzorewa then opened the proceedings at Smith's invitation. Speaking assertively, the bishop gave three concessions which would have to be given by the Rhodesian side for talks to begin: first,

After the failure of the talks across the Falls, even the facade of a united front amongst the nationalists was broken on 11 September, when Muzorewa expelled Nkomo and four of his deputies from the council after they suggested a new leadership election be held. ZAPU contacted Salisbury soon after, stating that they wished to enter talks directly with the government. Smith "opted for the unthinkable", in the words of Eliakim Sibanda, reasoning that for all of their differences, Nkomo was still, as Sibanda writes, "a seasoned and pragmatic politician", who commanded a not insignificant force of guerrillas. The ZAPU leader was popular, too, not only locally but also regionally and internationally. If he could be brought into an internal government, and ZIPRA onto the side of the security forces, Smith thought, ZANU would find it difficult to justify continuing the guerrilla war, and even if they did so, they would be less likely to win.

Dr Elliot Gabellah, Muzorewa's deputy in the UANC, told Smith that Nkomo was "the most balanced and experienced" of the nationalist leaders, and that most Ndebele now favoured open negotiation. He said that most Ndebele would support a deal between the government and Nkomo, and that Muzorewa probably would as well. Meetings between Nkomo and Smith were duly arranged, and the first took place in secret in October 1975. After a few clandestine sessions passed without major problems, the two leaders agreed to have formal talks in the capital in December 1975.

Nkomo was wary of being labelled a " sell-out" by his ZANU rivals, particularly Mugabe, so to prevent this from happening he first consulted Kaunda, Machel and Nyerere, the presidents of the Frontline States. Each of the presidents gave his approval to ZAPU's participation in direct talks, and with their blessing Nkomo and Smith signed a declaration of intent to negotiate on 1 December 1975. Constitutional negotiations between the government and ZAPU began in Salisbury ten days later. The ZAPU delegation proposed an immediate switch to black majority rule, a government elected on a "strictly non-racial" basis, and reluctantly offered some sweeteners for the Rhodesian white population, "which we detested", Nkomo says, including some reserved seats for whites in parliament., quoted in The talks dragged on for months afterwards, with little progress being made, though Smith notes the "congenial atmosphere, with both sides ready to crack a joke". Nkomo's account of the meetings is less favourable, stressing Smith's perceived intransigence: "We went to great lengths to offer conditions that the Rhodesian régime might find acceptable, but Smith would not budge."

After the failure of the talks across the Falls, even the facade of a united front amongst the nationalists was broken on 11 September, when Muzorewa expelled Nkomo and four of his deputies from the council after they suggested a new leadership election be held. ZAPU contacted Salisbury soon after, stating that they wished to enter talks directly with the government. Smith "opted for the unthinkable", in the words of Eliakim Sibanda, reasoning that for all of their differences, Nkomo was still, as Sibanda writes, "a seasoned and pragmatic politician", who commanded a not insignificant force of guerrillas. The ZAPU leader was popular, too, not only locally but also regionally and internationally. If he could be brought into an internal government, and ZIPRA onto the side of the security forces, Smith thought, ZANU would find it difficult to justify continuing the guerrilla war, and even if they did so, they would be less likely to win.

Dr Elliot Gabellah, Muzorewa's deputy in the UANC, told Smith that Nkomo was "the most balanced and experienced" of the nationalist leaders, and that most Ndebele now favoured open negotiation. He said that most Ndebele would support a deal between the government and Nkomo, and that Muzorewa probably would as well. Meetings between Nkomo and Smith were duly arranged, and the first took place in secret in October 1975. After a few clandestine sessions passed without major problems, the two leaders agreed to have formal talks in the capital in December 1975.

Nkomo was wary of being labelled a " sell-out" by his ZANU rivals, particularly Mugabe, so to prevent this from happening he first consulted Kaunda, Machel and Nyerere, the presidents of the Frontline States. Each of the presidents gave his approval to ZAPU's participation in direct talks, and with their blessing Nkomo and Smith signed a declaration of intent to negotiate on 1 December 1975. Constitutional negotiations between the government and ZAPU began in Salisbury ten days later. The ZAPU delegation proposed an immediate switch to black majority rule, a government elected on a "strictly non-racial" basis, and reluctantly offered some sweeteners for the Rhodesian white population, "which we detested", Nkomo says, including some reserved seats for whites in parliament., quoted in The talks dragged on for months afterwards, with little progress being made, though Smith notes the "congenial atmosphere, with both sides ready to crack a joke". Nkomo's account of the meetings is less favourable, stressing Smith's perceived intransigence: "We went to great lengths to offer conditions that the Rhodesian régime might find acceptable, but Smith would not budge."

The Victoria Falls Conference took place on 26 August 1975 aboard a

The Victoria Falls Conference took place on 26 August 1975 aboard a South African Railways

Transnet Freight Rail is a South African rail transport company, formerly known as Spoornet. It was part of the South African Railways and Harbours Administration, a state-controlled organisation that employed hundreds of thousands of people ...

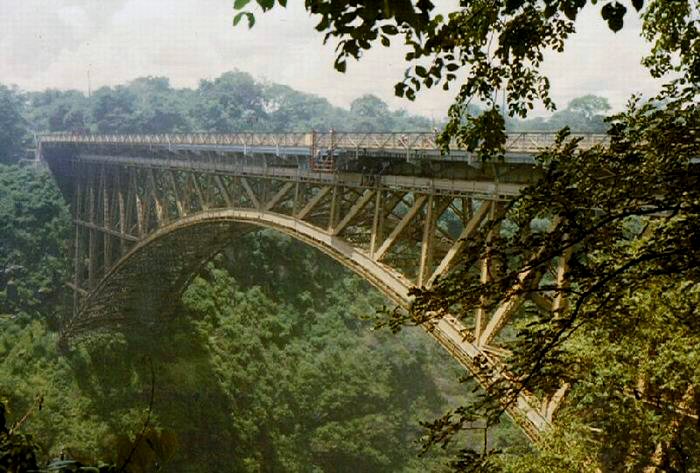

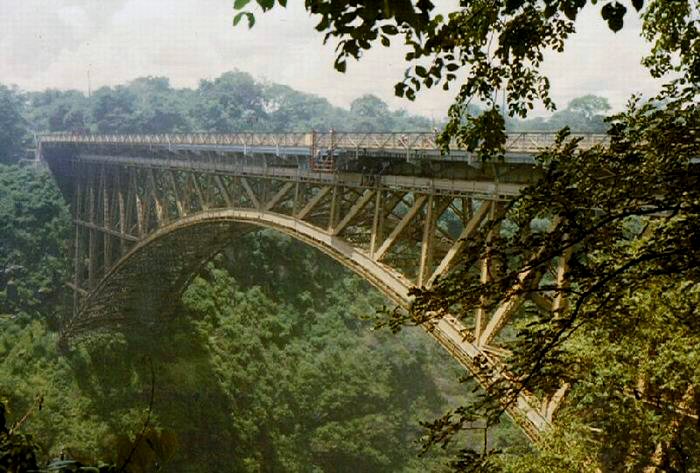

train halfway across the Victoria Falls Bridge

The Victoria Falls Bridge crosses the Zambezi River just below the Victoria Falls and is built over the Second Gorge of the falls. As the river forms the border between Zimbabwe and Zambia, the bridge links the two countries and has border post ...

on the border between the unrecognised state of Rhodesia

Rhodesia (, ), officially from 1970 the Republic of Rhodesia, was an unrecognised state in Southern Africa from 1965 to 1979, equivalent in territory to modern Zimbabwe. Rhodesia was the ''de facto'' successor state to the British colony of So ...

(today Zimbabwe) and Zambia. It was the culmination of the "détente" policy introduced and championed by B. J. Vorster

Balthazar Johannes "B. J." Vorster (; also known as John Vorster; 13 December 1915 – 10 September 1983) was a South African apartheid politician who served as the prime minister of South Africa from 1966 to 1978 and the fourth state presiden ...

, the Prime Minister of South Africa, which was then under apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

and was attempting to improve its relations with the Frontline States

The Frontline States (FLS) were a loose coalition of African countries from the 1960s to the early 1990s committed to ending ''apartheid'' and white minority rule in South Africa and Rhodesia. The FLS included Angola, Botswana, Lesotho, Mozambique, ...

to Rhodesia's north, west and east by helping to produce a settlement in Rhodesia. The participants in the conference were a delegation led by the Rhodesian Prime Minister Ian Smith

Ian Douglas Smith (8 April 1919 – 20 November 2007) was a Rhodesian politician, farmer, and fighter pilot who served as Prime Minister of Rhodesia (known as Southern Rhodesia until October 1964 and now known as Zimbabwe) from 1964 to 1 ...

on behalf of his government, and a nationalist delegation attending under the banner of Abel Muzorewa

Abel Tendekayi Muzorewa (14 April 1925 – 8 April 2010), also commonly referred to as Bishop Muzorewa, was a Zimbabwean bishop and politician who served as the first and only Prime Minister of Zimbabwe Rhodesia from the Internal Settlement to ...

's African National Council

The United African National Council (UANC) is a political party in Zimbabwe. It was briefly the ruling party during 1979–1980, when its leader Abel Muzorewa was Prime Minister.

History

The party was founded by Muzorewa in 1971.< ...

(UANC), which for this conference also incorporated delegates from the Zimbabwe African National Union

The Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) was a militant organisation that fought against white minority rule in Rhodesia, formed as a split from the Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU). ZANU split in 1975 into wings loyal to Robert Mugab ...

(ZANU), the Zimbabwe African People's Union

The Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU) is a Zimbabwean political party. It is a militant organization and political party that campaigned for majority rule in Rhodesia, from its founding in 1961 until 1980. In 1987, it merged with the Zim ...

(ZAPU) and the Front for the Liberation of Zimbabwe The Front for the Liberation of Zimbabwe (FROLIZI) was an African nationalist organisation established in opposition to the white minority government of Rhodesia. It was announced in Lusaka, Zambia in October 1971 as a merger of the two principal Af ...

(FROLIZI). Vorster and the Zambian President Kenneth Kaunda

Kenneth David Kaunda (28 April 1924 – 17 June 2021), also known as KK, was a Zambian politician who served as the first President of Zambia from 1964 to 1991. He was at the forefront of the struggle for independence from British rule. Diss ...

acted as mediators in the conference, which was held on the border in an attempt to provide a venue both sides would accept as neutral.

The conference failed to produce a settlement, breaking up on the same day it began with each side blaming the other for its unsuccessful outcome. Smith believed the nationalists were being unreasonable by requesting preconditions for talks—which they had previously agreed not to do—and asking for diplomatic immunity for their leaders and fighters. The nationalists contended that Smith was being deliberately intransigent and that they did not believe he was sincere in seeking an agreement if he was so adamant about not giving diplomatic immunity. Direct talks between the government and the Zimbabwe African People's Union followed in December 1975, but these also failed to produce any significant progress. The Victoria Falls Conference, the détente initiative and the associated ceasefire, though unsuccessful, did affect the course of the Rhodesian Bush War

The Rhodesian Bush War, also called the Second as well as the Zimbabwe War of Liberation, was a civil conflict from July 1964 to December 1979 in the List of states with limited recognition, unrecognised country of Rhodesia (later Zimbabwe-Rh ...

, as they gave the nationalist guerrillas significant time to regroup and reorganise themselves following the decisive security force counter-campaign of 1973–74. A further conference would follow in the Geneva Conference in 1976 .

Background

Harold Wilson

James Harold Wilson, Baron Wilson of Rievaulx, (11 March 1916 – 24 May 1995) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from October 1964 to June 1970, and again from March 1974 to April 1976. He ...

and the predominantly white minority government of the self-governing colony

In the British Empire, a self-governing colony was a colony with an elected government in which elected rulers were able to make most decisions without referring to the colonial power with nominal control of the colony. This was in contrast t ...

of Rhodesia

Rhodesia (, ), officially from 1970 the Republic of Rhodesia, was an unrecognised state in Southern Africa from 1965 to 1979, equivalent in territory to modern Zimbabwe. Rhodesia was the ''de facto'' successor state to the British colony of So ...

, led by the Prime Minister Ian Smith

Ian Douglas Smith (8 April 1919 – 20 November 2007) was a Rhodesian politician, farmer, and fighter pilot who served as Prime Minister of Rhodesia (known as Southern Rhodesia until October 1964 and now known as Zimbabwe) from 1964 to 1 ...

, were unable to agree terms for the latter's full independence. Rhodesia unilaterally declared independence on 11 November 1965. This was deemed illegal by Britain and the United Nations (UN), each of which imposed economic sanctions on Rhodesia.

The two most prominent black nationalist parties in Rhodesia were the Zimbabwe African National Union

The Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) was a militant organisation that fought against white minority rule in Rhodesia, formed as a split from the Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU). ZANU split in 1975 into wings loyal to Robert Mugab ...

(ZANU)—a predominantly Shona

Shona often refers to:

* Shona people, a Southern African people

* Shona language, a Bantu language spoken by Shona people today

Shona may also refer to:

* ''Shona'' (album), 1994 album by New Zealand singer Shona Laing

* Shona (given name)

* S ...

movement, influenced by Chinese Maoism

Maoism, officially called Mao Zedong Thought by the Chinese Communist Party, is a variety of Marxism–Leninism that Mao Zedong developed to realise a socialist revolution in the agricultural, pre-industrial society of the Republic of Ch ...

—and the Zimbabwe African People's Union

The Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU) is a Zimbabwean political party. It is a militant organization and political party that campaigned for majority rule in Rhodesia, from its founding in 1961 until 1980. In 1987, it merged with the Zim ...

(ZAPU), which was Marxist–Leninist, and mostly Ndebele

Ndebele may refer to:

*Southern Ndebele people, located in South Africa

*Northern Ndebele people, located in Zimbabwe and Botswana

Languages

* Southern Ndebele language, the language of the South Ndebele

* Northern Ndebele language, the language ...

. ZANU and its military wing, the Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army

Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army (ZANLA) was the military wing of the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU), a militant African nationalist organisation that participated in the Rhodesian Bush War against white minority rule of Rhode ...

(ZANLA), received considerable backing in training, materiel and finances from the People's Republic of China and its allies, while the Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Pact (WP) or Treaty of Warsaw, formally the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance, was a collective defense treaty signed in Warsaw, Poland, between the Soviet Union and seven other Eastern Bloc socialist republi ...

and associated nations, prominently Cuba, gave similar support to ZAPU and its Zimbabwe People's Revolutionary Army

Zimbabwe People's Revolutionary Army (ZIPRA) was the military wing of the Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU), a Marxist–Leninist political party in Rhodesia. It participated in the Rhodesian Bush War against white minority rule of Rhod ...

(ZIPRA).; ZAPU and ZIPRA were headed by Joshua Nkomo

Joshua Mqabuko Nyongolo Nkomo (19 June 1917 – 1 July 1999) was a Zimbabwean revolutionary and Matabeleland politician who served as Vice-President of Zimbabwe from 1990 until his death in 1999. He founded and led the Zimbabwe African People's ...

throughout their existence, while the Reverend Ndabaningi Sithole

Ndabaningi Sithole (21 July 1920 – 12 December 2000) founded the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU), a militant organisation that opposed the government of Rhodesia, in July 1963.Veenhoven, Willem Adriaan, Ewing, and Winifred Crum. ''Cas ...

founded and initially led ZANU. The two rival nationalist movements began what they called their "Second ''Chimurenga

''Chimurenga'' is a word in the Shona language. The Ndebele equivalent, though not as widely used since the majority of Zimbabweans are Shona speaking, is ''Umvukela'', meaning "revolutionary struggle" or uprising. In specific historical terms ...

''" against the Rhodesian government and security forces

Security forces are statutory organizations with internal security mandates. In the legal context of several nations, the term has variously denoted police and military units working in concert, or the role of military and paramilitary forces (su ...

, and, while based outside the country, sent groups of guerrillas into Rhodesia at regular intervals. Most of these early incursions, which had little success, were perpetrated by ZIPRA.

Wilson and Smith held abortive talks aboard HMS ''Tiger'' in 1966 and HMS ''Fearless'' two years later. A constitution was agreed upon by the Rhodesian and British governments in November 1971, but when the British gauged Rhodesian public opinion in early 1972 they abandoned the deal on the grounds that they perceived most blacks to be against it. The Rhodesian Bush War

The Rhodesian Bush War, also called the Second as well as the Zimbabwe War of Liberation, was a civil conflict from July 1964 to December 1979 in the List of states with limited recognition, unrecognised country of Rhodesia (later Zimbabwe-Rh ...

suddenly re-erupted after two years of relative inactivity on 21 December 1972 when ZANLA attacked Altena Farm near Centenary

{{other uses, Centennial (disambiguation), Centenary (disambiguation)

A centennial, or centenary in British English, is a 100th anniversary or otherwise relates to a century, a period of 100 years.

Notable events

Notable centennial events at a ...

in the country's north-east. The security forces mounted a strong counter-campaign and by the end of 1974 had reduced the number of guerrillas active within the country to under 300. In the period October–November 1974, the Rhodesians killed more nationalist fighters than in the previous two years combined.

Mozambican independence and the South African "détente" initiative

The effect of the security forces' decisive counter-campaign was undone by two drastic changes to the geopolitical situation in 1974 and 1975, each relating to one of the Rhodesian government's two main backers, Portugal and South Africa. InLisbon

Lisbon (; pt, Lisboa ) is the capital and largest city of Portugal, with an estimated population of 544,851 within its administrative limits in an area of 100.05 km2. Lisbon's urban area extends beyond the city's administrative limits w ...

, a military coup

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. It is typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with its members identifiable by their distinct ...

on 25 April 1974 replaced the right-wing '' Estado Novo'' administration with a leftist government opposed to the unpopular Colonial War

Colonial war (in some contexts referred to as small war) is a blanket term relating to the various conflicts that arose as the result of overseas territories being settled by foreign powers creating a colony. The term especially refers to wars ...

in Angola

, national_anthem = "Angola Avante"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capital = Luanda

, religion =

, religion_year = 2020

, religion_ref =

, coordinat ...

, Mozambique and Portugal's other African territories. Following this coup, which became known as the Carnation Revolution

The Carnation Revolution ( pt, Revolução dos Cravos), also known as the 25 April ( pt, 25 de Abril, links=no), was a military coup by left-leaning military officers that overthrew the authoritarian Estado Novo regime on 25 April 1974 in Lisbo ...

, Portuguese leadership was hurriedly withdrawn from Lisbon's overseas territories, each of which was earmarked for an immediate handover to communist guerrillas. Brief, frenzied negotiations with FRELIMO

FRELIMO (; from the Portuguese , ) is a democratic socialist political party in Mozambique. It is the dominant party in Mozambique and has won a majority of the seats in the Assembly of the Republic in every election since the country's firs ...

in Mozambique preceded the country's independence on 25 June 1975; FRELIMO took power without contesting an election, while Samora Machel

Samora Moisés Machel (29 September 1933 – 19 October 1986) was a Mozambican military commander and political leader. A socialist in the tradition of Marxism–Leninism, he served as the first President of Mozambique from the country's ...

assumed the presidency. Now that Mozambique was under a friendly government, ZANLA could freely base themselves there with the full support of Machel and FRELIMO, with whom an alliance had already existed since the late 1960s. The Rhodesian Security Forces, on the other hand, now had a further of border to defend and had to rely on South Africa alone for imports.

The second event was more surprising for the Rhodesians. In late 1974, the government of Rhodesia's main ally and backer, South Africa, adopted a doctrine of "détente" with the Frontline States

The Frontline States (FLS) were a loose coalition of African countries from the 1960s to the early 1990s committed to ending ''apartheid'' and white minority rule in South Africa and Rhodesia. The FLS included Angola, Botswana, Lesotho, Mozambique, ...

. In an attempt to resolve the situation in Rhodesia, the South African Prime Minister B. J. Vorster

Balthazar Johannes "B. J." Vorster (; also known as John Vorster; 13 December 1915 – 10 September 1983) was a South African apartheid politician who served as the prime minister of South Africa from 1966 to 1978 and the fourth state presiden ...

negotiated a deal: the Zambian President Kenneth Kaunda

Kenneth David Kaunda (28 April 1924 – 17 June 2021), also known as KK, was a Zambian politician who served as the first President of Zambia from 1964 to 1991. He was at the forefront of the struggle for independence from British rule. Diss ...

would prevent guerrilla infiltrations into Rhodesia from his country, and in return the Rhodesian Prime Minister Ian Smith

Ian Douglas Smith (8 April 1919 – 20 November 2007) was a Rhodesian politician, farmer, and fighter pilot who served as Prime Minister of Rhodesia (known as Southern Rhodesia until October 1964 and now known as Zimbabwe) from 1964 to 1 ...

would agree to a ceasefire

A ceasefire (also known as a truce or armistice), also spelled cease fire (the antonym of 'open fire'), is a temporary stoppage of a war in which each side agrees with the other to suspend aggressive actions. Ceasefires may be between state ac ...

and "release all political detainees"—the leaders of ZANU and ZAPU—who would then attend a conference in Rhodesia, united under a single banner and led by Bishop Abel Muzorewa

Abel Tendekayi Muzorewa (14 April 1925 – 8 April 2010), also commonly referred to as Bishop Muzorewa, was a Zimbabwean bishop and politician who served as the first and only Prime Minister of Zimbabwe Rhodesia from the Internal Settlement to ...

and his African National Council

The United African National Council (UANC) is a political party in Zimbabwe. It was briefly the ruling party during 1979–1980, when its leader Abel Muzorewa was Prime Minister.

History

The party was founded by Muzorewa in 1971.< ...

(UANC). Vorster hoped that if this were successful the Frontline States would enter full diplomatic relations with South Africa and allow it to retain apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

. Under pressure from Pretoria

Pretoria () is South Africa's administrative capital, serving as the seat of the executive branch of government, and as the host to all foreign embassies to South Africa.

Pretoria straddles the Apies River and extends eastward into the foothi ...

to accept the terms, the Rhodesians agreed on 11 December 1974 and followed the terms of the ceasefire; Rhodesian military actions were temporarily halted and troops were ordered to allow retreating guerrillas to leave unhindered. Vorster withdrew some 2,000 members of the South African Police

The South African Police (SAP) was the national police force and law enforcement agency in South Africa from 1913 to 1994; it was the ''de facto'' police force in the territory of South West Africa (Namibia) from 1939 to 1981. After South Af ...

(SAP) from forward bases in Rhodesia, and by August 1975 had pulled the SAP out of Rhodesia completely.

The nationalists, on the other hand, ignored the agreed terms and used the sudden cessation of security force activity as an opportunity to regroup and re-establish themselves both inside and outside the country. Guerrilla operations continued: an average of six incidents a day were reported inside Rhodesia over the following months. Far from being seen as a gesture of potential reconciliation, the ceasefire and release of the nationalist leaders gave the message to the rural population that the security forces had been defeated, and that the guerrillas were in the process of emulating FRELIMO's victory in Mozambique. ZANU and ZANLA were unable to totally capitalise on the situation, however, because of internal conflict which had started earlier in 1974. Some ordinary ZANU cadres perceived the ZANU High Command members in Lusaka

Lusaka (; ) is the capital and largest city of Zambia. It is one of the fastest-developing cities in southern Africa. Lusaka is in the southern part of the central plateau at an elevation of about . , the city's population was about 3.3 millio ...

, the Zambian capital, to be following a luxurious lifestyle, contrary to the party's Maoist principles. This culminated in the Nhari rebellion

The Nhari Rebellion occurred in November 1974, amidst the Rhodesian Bush War, when members of the Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army (ZANLA) in Chifombo, Zambia (near the border with Mozambique) rebelled against the leadership of the politi ...

of November 1974, in which mutinous guerrillas were forcibly put down by the ZANU defence chief, Josiah Tongogara

Josiah Magama Tongogara (4 February 1938 – 26 December 1979) was a commander of the ZANLA guerrilla army in Rhodesia. He was the brother of current Zimbabwe President Emmerson Mnangagwa's second wife, Jayne. He attended the Lancaster House co ...

. The ZANU and ZAPU leaders imprisoned in Rhodesia were released in December 1974 as part of the "détente" deal. Robert Mugabe

Robert Gabriel Mugabe (; ; 21 February 1924 – 6 September 2019) was a Zimbabwean revolutionary and politician who served as Prime Minister of Zimbabwe from 1980 to 1987 and then as President from 1987 to 2017. He served as Leader of the ...

had been elected ZANU president while they were incarcerated, though this was disputed by its founding leader, the Reverend Ndabaningi Sithole

Ndabaningi Sithole (21 July 1920 – 12 December 2000) founded the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU), a militant organisation that opposed the government of Rhodesia, in July 1963.Veenhoven, Willem Adriaan, Ewing, and Winifred Crum. ''Cas ...

, who continued to be recognised as such by the Frontline States. On his release, Mugabe moved into Mozambique to consolidate his supremacy within ZANU and ZANLA, while Sithole prepared to take part in talks with the Rhodesian government as part of the UANC delegation. Sithole retained the ZANU leadership in the eyes of the Frontline States until late 1975.

The Victoria Falls Conference

According to the terms agreed in December 1974, the talks between the Rhodesian government and the UANC were to take place within Rhodesia, but in the event the black nationalist leaders were loath to attend a conference on ground they perceived as not neutral. The Rhodesians, however, were keen to adhere to the accord and meet at a Rhodesian venue. In an effort to placate both sides, Kaunda and Vorster relaxed the terms so that the two sides would instead meet aboard a train provided by the South African government, placed halfway across theVictoria Falls Bridge

The Victoria Falls Bridge crosses the Zambezi River just below the Victoria Falls and is built over the Second Gorge of the falls. As the river forms the border between Zimbabwe and Zambia, the bridge links the two countries and has border post ...

, on the Rhodesian–Zambian border. The Rhodesian delegates could therefore take their seats in Rhodesia and the nationalists, on the opposite side of the carriage, would be able to attend without leaving Zambia. As part of the détente policy, Kaunda and Vorster would act as mediators in the conference, which was set for 26 August 1975.

The UANC delegation was led, as expected, by Muzorewa and included Sithole representing ZANU, Nkomo for ZAPU and James Chikerema

James Robert Dambaza Chikerema (2 April 1925 – 22 March 2006) served as the President of the Front for the Liberation of Zimbabwe.Nyangoni, Wellington Winter. ''Africa in the United Nations System.'' Page 141. He changed his views on militant s ...

, the former ZAPU vice-president, for a third militant party, the Front for the Liberation of Zimbabwe The Front for the Liberation of Zimbabwe (FROLIZI) was an African nationalist organisation established in opposition to the white minority government of Rhodesia. It was announced in Lusaka, Zambia in October 1971 as a merger of the two principal Af ...

. According to Rhodesian intelligence, the various nationalist factions had not patched up their differences, were not prepared to accept Muzorewa as their leader and, to this end, were hoping that the conference failed to produce an agreement. The Rhodesians relayed these concerns to Pretoria, which told them firmly that the UANC would surely not risk losing the support of Kaunda and the Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere

Julius Kambarage Nyerere (; 13 April 1922 – 14 October 1999) was a Tanzanian anti-colonial activist, politician, and political theorist. He governed Tanganyika as prime minister from 1961 to 1962 and then as president from 1962 to 1964, af ...

by deliberately sabotaging the peace process. When the Rhodesians persisted in their complaints, citing evidence of nationalist infighting in Lusaka, the South Africans were terser still, eventually wiring Salisbury

Salisbury ( ) is a cathedral city in Wiltshire, England with a population of 41,820, at the confluence of the rivers Avon, Nadder and Bourne. The city is approximately from Southampton and from Bath.

Salisbury is in the southeast of ...

: "If you don't like what we are offering, you always have the alternative of going it alone!"

The conference started on the morning of 26 August as planned. The six Rhodesian delegates took their places first, then around 40 nationalists entered and crowded around Muzorewa on the opposite side of the cramped railway carriage. Vorster and Kaunda arrived and sat on the Rhodesian side, where there was more space, and each spoke in turn, giving their blessing to the negotiations. Muzorewa then opened the proceedings at Smith's invitation. Speaking assertively, the bishop gave three concessions which would have to be given by the Rhodesian side for talks to begin: first,

The conference started on the morning of 26 August as planned. The six Rhodesian delegates took their places first, then around 40 nationalists entered and crowded around Muzorewa on the opposite side of the cramped railway carriage. Vorster and Kaunda arrived and sat on the Rhodesian side, where there was more space, and each spoke in turn, giving their blessing to the negotiations. Muzorewa then opened the proceedings at Smith's invitation. Speaking assertively, the bishop gave three concessions which would have to be given by the Rhodesian side for talks to begin: first, one man, one vote

"One man, one vote", or "one person, one vote", expresses the principle that individuals should have equal representation in voting. This slogan is used by advocates of political equality to refer to such electoral reforms as universal suffrage, ...

was established by Muzorewa to be "a basic necessity"; second, an amnesty would have to be given for all guerrilla fighters, including those convicted of murder by the High Court in Salisbury; and finally, all of the nationalists would have to be given permission to return to Rhodesia as soon as possible to begin political campaigning. Smith replied calmly that Kaunda, Nyerere and Vorster had all assured him that the UANC had agreed not to demand preconditions for talks, and that Kaunda and Vorster had in fact confirmed this to him that same morning; his delegation was therefore surprised by Muzorewa's confrontational opening speech.

Smith says that his reply "provoked a flood of rhetoric"; the nationalists evaded his words and, one by one, gave passionate speeches about being "a suppressed people ... denied freedom in their own country" who only wanted to "return home and live normal, peaceful lives". Smith sat back and waited for them to finish, then responded that there was nothing stopping them from going home at any time and living peacefully if they so wished, and that they were in this situation by their own hand. They themselves, he said, had refused the Anglo-Rhodesian accord agreed four years previously, which he said had offered Rhodesian blacks "preferential franchise facilities", and they themselves had chosen to use "unconstitutional means and terrorism in order to overthrow the legal government of our country." The UANC delegates countered by railing against Smith even more strongly than before, repeating their previous arguments and rejecting the right of Britain to negotiate on their behalf. This argument went on for nine and a half hours before the conference broke up, Smith refusing outright to grant diplomatic immunity to the UANC's "terrorist leaders who bear responsibility for ... murders and other atrocities". Muzorewa said that he doubted Smith's sincerity in seeking a resolution if he was unwilling to grant such a "very small thing" as immunity to the nationalist leaders. The conference broke up without any agreement or progress having been made.

Aftermath: direct talks between the government and ZAPU in Salisbury

After the failure of the talks across the Falls, even the facade of a united front amongst the nationalists was broken on 11 September, when Muzorewa expelled Nkomo and four of his deputies from the council after they suggested a new leadership election be held. ZAPU contacted Salisbury soon after, stating that they wished to enter talks directly with the government. Smith "opted for the unthinkable", in the words of Eliakim Sibanda, reasoning that for all of their differences, Nkomo was still, as Sibanda writes, "a seasoned and pragmatic politician", who commanded a not insignificant force of guerrillas. The ZAPU leader was popular, too, not only locally but also regionally and internationally. If he could be brought into an internal government, and ZIPRA onto the side of the security forces, Smith thought, ZANU would find it difficult to justify continuing the guerrilla war, and even if they did so, they would be less likely to win.

Dr Elliot Gabellah, Muzorewa's deputy in the UANC, told Smith that Nkomo was "the most balanced and experienced" of the nationalist leaders, and that most Ndebele now favoured open negotiation. He said that most Ndebele would support a deal between the government and Nkomo, and that Muzorewa probably would as well. Meetings between Nkomo and Smith were duly arranged, and the first took place in secret in October 1975. After a few clandestine sessions passed without major problems, the two leaders agreed to have formal talks in the capital in December 1975.

Nkomo was wary of being labelled a " sell-out" by his ZANU rivals, particularly Mugabe, so to prevent this from happening he first consulted Kaunda, Machel and Nyerere, the presidents of the Frontline States. Each of the presidents gave his approval to ZAPU's participation in direct talks, and with their blessing Nkomo and Smith signed a declaration of intent to negotiate on 1 December 1975. Constitutional negotiations between the government and ZAPU began in Salisbury ten days later. The ZAPU delegation proposed an immediate switch to black majority rule, a government elected on a "strictly non-racial" basis, and reluctantly offered some sweeteners for the Rhodesian white population, "which we detested", Nkomo says, including some reserved seats for whites in parliament., quoted in The talks dragged on for months afterwards, with little progress being made, though Smith notes the "congenial atmosphere, with both sides ready to crack a joke". Nkomo's account of the meetings is less favourable, stressing Smith's perceived intransigence: "We went to great lengths to offer conditions that the Rhodesian régime might find acceptable, but Smith would not budge."

After the failure of the talks across the Falls, even the facade of a united front amongst the nationalists was broken on 11 September, when Muzorewa expelled Nkomo and four of his deputies from the council after they suggested a new leadership election be held. ZAPU contacted Salisbury soon after, stating that they wished to enter talks directly with the government. Smith "opted for the unthinkable", in the words of Eliakim Sibanda, reasoning that for all of their differences, Nkomo was still, as Sibanda writes, "a seasoned and pragmatic politician", who commanded a not insignificant force of guerrillas. The ZAPU leader was popular, too, not only locally but also regionally and internationally. If he could be brought into an internal government, and ZIPRA onto the side of the security forces, Smith thought, ZANU would find it difficult to justify continuing the guerrilla war, and even if they did so, they would be less likely to win.

Dr Elliot Gabellah, Muzorewa's deputy in the UANC, told Smith that Nkomo was "the most balanced and experienced" of the nationalist leaders, and that most Ndebele now favoured open negotiation. He said that most Ndebele would support a deal between the government and Nkomo, and that Muzorewa probably would as well. Meetings between Nkomo and Smith were duly arranged, and the first took place in secret in October 1975. After a few clandestine sessions passed without major problems, the two leaders agreed to have formal talks in the capital in December 1975.

Nkomo was wary of being labelled a " sell-out" by his ZANU rivals, particularly Mugabe, so to prevent this from happening he first consulted Kaunda, Machel and Nyerere, the presidents of the Frontline States. Each of the presidents gave his approval to ZAPU's participation in direct talks, and with their blessing Nkomo and Smith signed a declaration of intent to negotiate on 1 December 1975. Constitutional negotiations between the government and ZAPU began in Salisbury ten days later. The ZAPU delegation proposed an immediate switch to black majority rule, a government elected on a "strictly non-racial" basis, and reluctantly offered some sweeteners for the Rhodesian white population, "which we detested", Nkomo says, including some reserved seats for whites in parliament., quoted in The talks dragged on for months afterwards, with little progress being made, though Smith notes the "congenial atmosphere, with both sides ready to crack a joke". Nkomo's account of the meetings is less favourable, stressing Smith's perceived intransigence: "We went to great lengths to offer conditions that the Rhodesian régime might find acceptable, but Smith would not budge."

Notes

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * {{Good article 1975 conferences 1975 in international relations 1975 in Rhodesia 20th-century diplomatic conferences Diplomatic conferences in Zambia Diplomatic conferences in Rhodesia Foreign relations of Rhodesia History of Rhodesia Rhodesian Bush War Rhodesia–Zambia relations August 1975 events in Africa