United States v. More on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''United States v. More'', 7 U.S. (3 Cranch) 159 (1805), was a

The

The

The D.C. justices of the peace were appointed by the President, in a number at his discretion, and confirmed by the Senate for five-year terms. A D.C. justice of the peace had jurisdiction over "all matters, civil and criminal, and in whatever relates to the conservation of the peace" within their county.District of Columbia Organic Act of 1801, § 11, 2 Stat. 103, 107. The District of Columbia was divided into two counties: Washington County, east of the

The D.C. justices of the peace were appointed by the President, in a number at his discretion, and confirmed by the Senate for five-year terms. A D.C. justice of the peace had jurisdiction over "all matters, civil and criminal, and in whatever relates to the conservation of the peace" within their county.District of Columbia Organic Act of 1801, § 11, 2 Stat. 103, 107. The District of Columbia was divided into two counties: Washington County, east of the

The availability of criminal appeals to the Supreme Court by means of writs of error from the circuit courts was perhaps an open question prior to ''More''. In

The availability of criminal appeals to the Supreme Court by means of writs of error from the circuit courts was perhaps an open question prior to ''More''. In

Benjamin More was one of two of D.C. justices of peace in

Benjamin More was one of two of D.C. justices of peace in

The D.C. circuit court judges hearing the

The D.C. circuit court judges hearing the

prospective

holding that it "cannot affect that justice of the peace during his continuance in office; whatever effect it may have upon those justices who have been appointed to office since the passing of the act." Contemporary media accounts reported that the circuit court had held that fee-elimination provision of the May 23, 1802 act unconstitutional, rather than interpreting it as prospective.O'Fallon, 1993, at 51 n.42. According to O'Fallon, this is evidence that Cranch's published opinion (as reported by himself) may have differed from his oral opinion.

On February 13,

On February 13,

On March 2, 1805, writing for a unanimous Court, Chief Justice

On March 2, 1805, writing for a unanimous Court, Chief Justice

United States Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

case in which the Court held that it had no jurisdiction to hear appeals from criminal cases in the circuit courts by writs of error

In law, an appeal is the process in which cases are reviewed by a higher authority, where parties request a formal change to an official decision. Appeals function both as a process for error correction as well as a process of clarifying and ...

. Relying on the Exceptions Clause

Article Three of the United States Constitution establishes the judicial branch of the U.S. federal government. Under Article Three, the judicial branch consists of the Supreme Court of the United States, as well as lower courts created by Congres ...

, ''More'' held that Congress's enumerated grants of appellate jurisdiction

A court of appeals, also called a court of appeal, appellate court, appeal court, court of second instance or second instance court, is any court of law that is empowered to hear an appeal of a trial court or other lower tribunal. In much of t ...

to the Court operated as an exercise of Congress's power to eliminate all other forms of appellate jurisdiction.

The second of forty-one criminal cases heard by the Marshall Court

The Marshall Court refers to the Supreme Court of the United States from 1801 to 1835, when John Marshall served as the fourth Chief Justice of the United States. Marshall served as Chief Justice until his death, at which point Roger Taney ...

, ''More'' ensured that the Court's criminal jurisprudence would be limited to writs of error from the state (and later, territorial) courts, original habeas petitions and writs of error from habeas petitions in the circuit courts, and certificates of division and mandamus

(; ) is a judicial remedy in the form of an order from a court to any government, subordinate court, corporation, or public authority, to do (or forbear from doing) some specific act which that body is obliged under law to do (or refrain from ...

from the circuit courts. Congress did not grant the Court jurisdiction to hear writs of error from the circuit courts in criminal cases until 1889, for capital crimes, and 1891, for other "infamous" crimes. The Judicial Code of 1911

The Judicial Code of 1911 () abolished the United States circuit courts and transferred their trial jurisdiction to the U.S. district courts.

In 1911, the United States Congress created a single code encompassing all statutes related to the judici ...

abolished the circuit courts, transferred the trial of crimes to the district courts, and extended the Court's appellate jurisdiction to all crimes.Brent D. Stratton, ''Criminal Law: The Attenuation Exception to the Exclusionary Rule: A Study in Attenuated Principle and Dissipated Logic'', 75 139, 139 n.1 (1984). But, these statutory grants were construed not to permit writs of error filed by the prosecution, as in ''More''.

''More'' arose from the same Federalist

The term ''federalist'' describes several political beliefs around the world. It may also refer to the concept of parties, whose members or supporters called themselves ''Federalists''.

History Europe federation

In Europe, proponents of de ...

/ Jeffersonian political dispute over the judiciary that gave rise to ''Marbury v. Madison

''Marbury v. Madison'', 5 U.S. (1 Cranch) 137 (1803), was a List of landmark court decisions in the United States, landmark Supreme Court of the United States, U.S. Supreme Court case that established the principle of Judicial review in the Uni ...

'' (1803) and ''Stuart v. Laird

''Stuart v. Laird'', 5 U.S. (1 Cranch) 299 (1803), was a case decided by United States Supreme Court notably a week after its famous decision in '' Marbury v. Madison''.

''Stuart'' dealt with a judgment of a circuit judge whose position had bee ...

'' (1803). Benjamin More, a justice of the peace

A justice of the peace (JP) is a judicial officer of a lower or ''puisne'' court, elected or appointed by means of a commission ( letters patent) to keep the peace. In past centuries the term commissioner of the peace was often used with the sa ...

in the District of Columbia

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

, argued that the repeal of statutory provisions authorizing compensation for his office violated the salary-protection guarantees for federal judges in Article Three of the United States Constitution

Article Three of the United States Constitution establishes the judicial branch of the U.S. federal government. Under Article Three, the judicial branch consists of the Supreme Court of the United States, as well as lower courts created by Congres ...

. Below, a divided panel of the United States Circuit Court of the District of Columbia

The United States Circuit Court of the District of Columbia (in case citations, C.C.D.C.) was a United States federal court which existed from 1801 to 1863. The court was created by the District of Columbia Organic Act of 1801.

History

The D.C. ci ...

had sided with More, interpreted the repeal act prospectively, and sustained his demurrer

A demurrer is a pleading in a lawsuit that objects to or challenges a pleading filed by an opposing party. The word ''demur'' means "to object"; a ''demurrer'' is the document that makes the objection. Lawyers informally define a demurrer as a de ...

to the criminal indictment for the common law crime

Common law offences are crimes under English criminal law, the related criminal law of some Commonwealth countries, and under some U.S. State laws. They are offences under the common law, developed entirely by the law courts, having no specific ...

of exacting illegal fees under color of office.

Background

United States presidential election, 1800

The

The Federalist Party

The Federalist Party was a Conservatism in the United States, conservative political party which was the first political party in the United States. As such, under Alexander Hamilton, it dominated the national government from 1789 to 1801.

De ...

and the Democratic-Republican Party

The Democratic-Republican Party, known at the time as the Republican Party and also referred to as the Jeffersonian Republican Party among other names, was an American political party founded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in the early ...

comprised the First Party System

The First Party System is a model of American politics used in history and political science to periodize the political party system that existed in the United States between roughly 1792 and 1824. It featured two national parties competing for ...

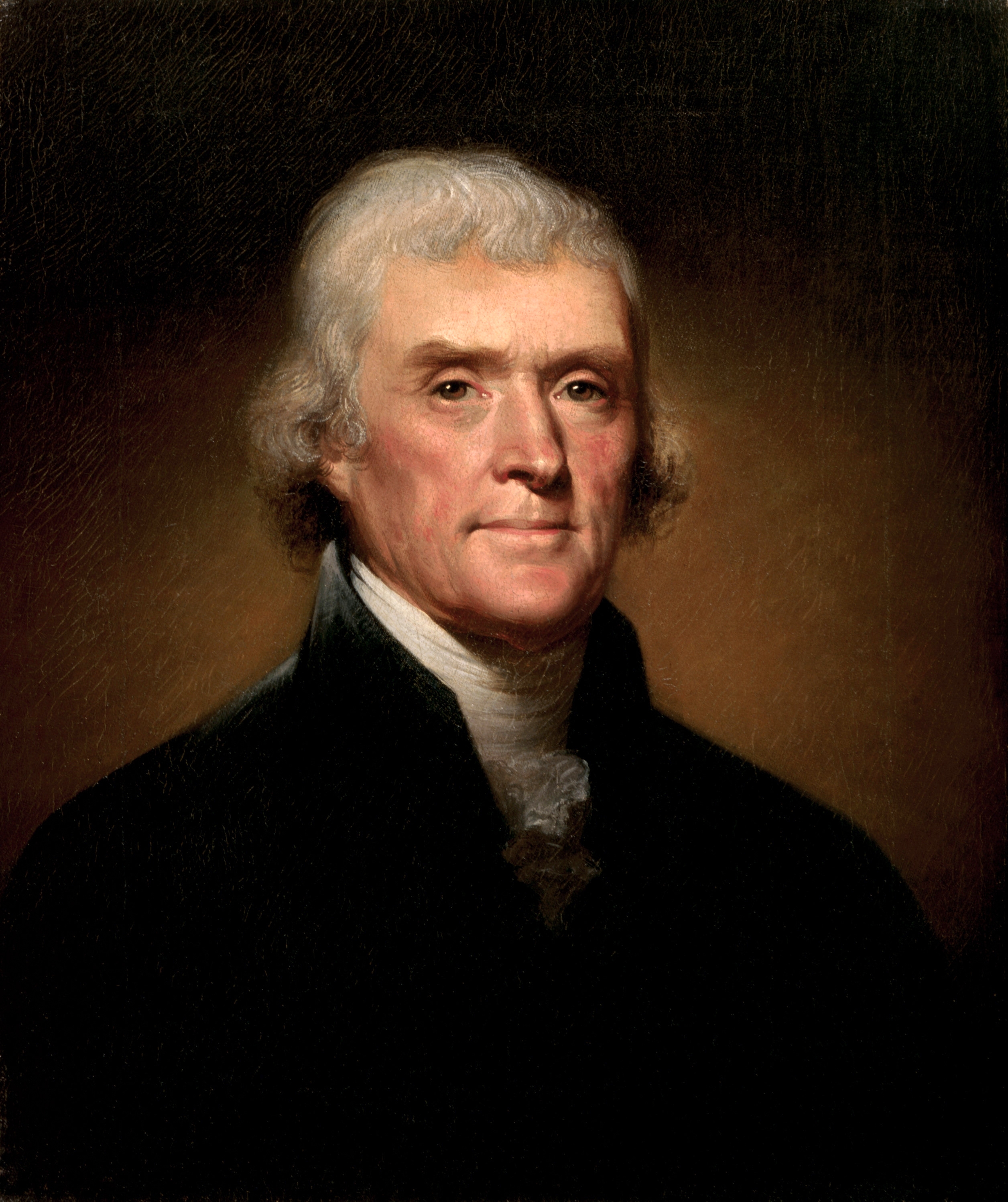

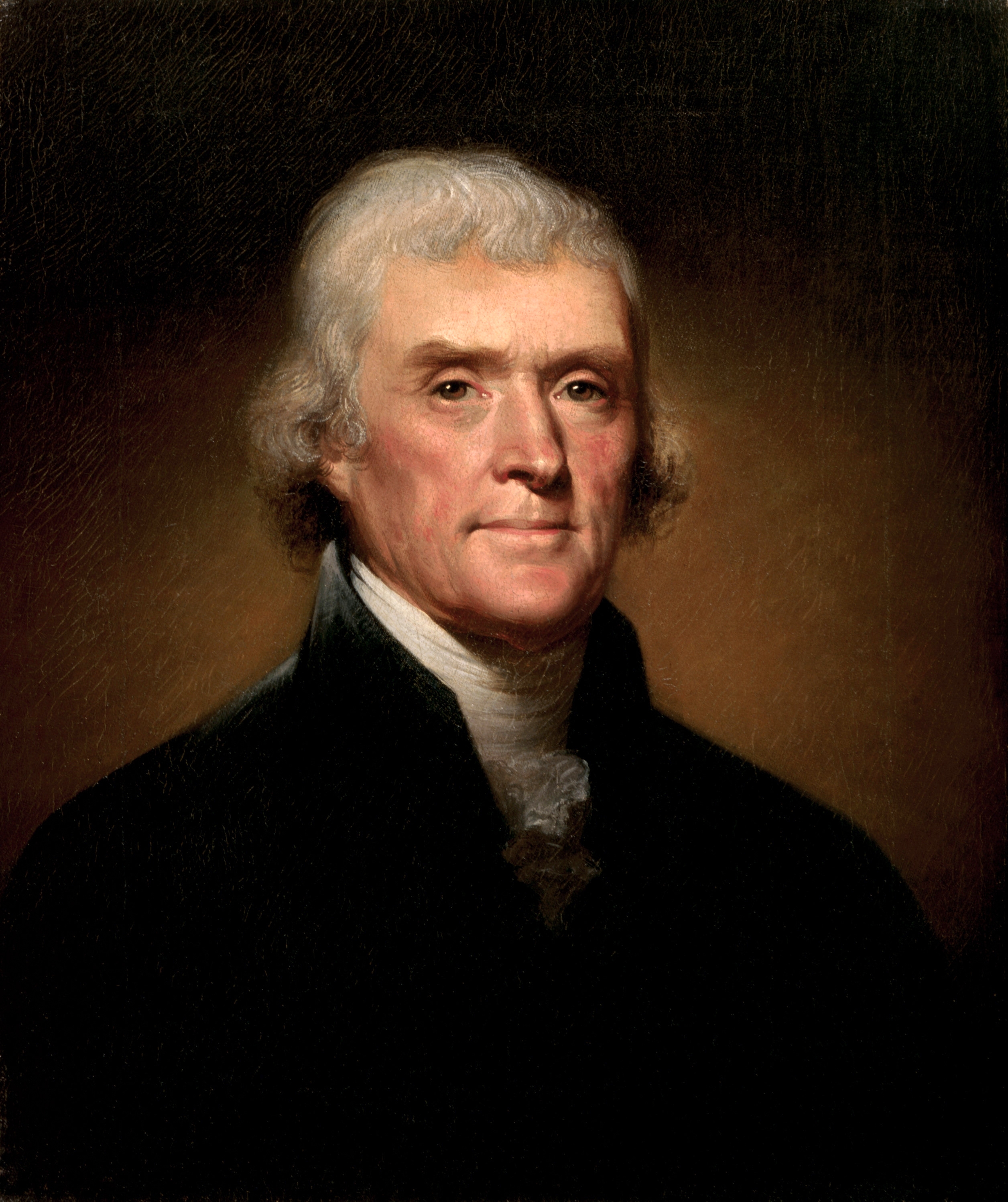

in the United States. Democratic-Republican Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

defeated Federalist John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Befor ...

in the 1800 presidential election. Jefferson's party also took control of Congress in the House

A house is a single-unit residential building. It may range in complexity from a rudimentary hut to a complex structure of wood, masonry, concrete or other material, outfitted with plumbing, electrical, and heating, ventilation, and air condi ...

and Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

elections. After the elections, the lame duck Federalist administration passed the Judiciary Act of 1801 (the "Midnight Judges Act

The Midnight Judges Act (also known as the Judiciary Act of 1801; , and officially An act to provide for the more convenient organization of the Courts of the United States) represented an effort to solve an issue in the U.S. Supreme Court during t ...

"), creating 16 new circuit judgeships to preside in the circuit courts (as opposed to the district judges and the Supreme Court justices riding circuit

In the United States, circuit riding was the practice of a judge, sometimes referred to as a circuit rider, traveling to a judicial district (referred to as a circuit) to preside over court cases there. A defining feature of American federal cour ...

).Murrin, Johnson, McPherson, et al Murrin, Johnson, McPherson, et al Along with the District of Columbia Organic Act of 1801

The District of Columbia Organic Act of 1801, officially An Act Concerning the District of Columbia (6th Congress, 2nd Sess., ch. 15, , February 27, 1801), is an organic act enacted by the United States Congress in accordance with Article 1, Sec ...

(the "Organic Act"), the statutes created many judicial vacancies, and Adams filled nearly all of these judgeships on his last day in office. Marshall, in his dual role as Adams' Secretary of State, failed to deliver some of these commissions before leaving office.

Companion cases

Immediately after his inauguration, Jefferson instructed his Secretary of State,James Madison

James Madison Jr. (March 16, 1751June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father. He served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for hi ...

, to stop delivery on all outstanding commissions., 1985, at 19. Further, an act of March 8, 1802 abolished the circuit court judgeships created by the Midnight Judges Act (15 of which had already been filled), restoring the system created under the 1789

Events

January–March

* January – Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès publishes the pamphlet ''What Is the Third Estate?'' ('), influential on the French Revolution.

* January 7 – The 1788-89 United States presidential election a ...

and 1793

The French Republic introduced the French Revolutionary Calendar starting with the year I.

Events

January–June

* January 7 – The Ebel riot occurs in Sweden.

* January 9 – Jean-Pierre Blanchard becomes the first to fl ...

acts. Federalists viewed this as unconstitutional and looked to the then-pending case of ''Marbury v. Madison

''Marbury v. Madison'', 5 U.S. (1 Cranch) 137 (1803), was a List of landmark court decisions in the United States, landmark Supreme Court of the United States, U.S. Supreme Court case that established the principle of Judicial review in the Uni ...

''—concerning a confirmed D.C. justice of the peace who had not received his commission—as a test case for the constitutionality of the repeal. The next session of the Supreme Court was in June, one month before the repeal would take effect. But, the Judiciary Act of 1802 The Judiciary Act of 1802 () was a Federal statute, enacted on April 29, 1802, to reorganize the federal court system. It restored some elements of the Judiciary Act of 1801, which had been adopted by the Federalist majority in the previous Congres ...

delayed the Court's next session until February 1803, and made other changes to the structure of the judicial system.

More broadly, Jefferson removed 146 of 316 (46%) incumbent, second-level, appointed federal officials, including 13 U.S. Attorneys

United States attorneys are officials of the U.S. Department of Justice who serve as the chief federal law enforcement officers in each of the 94 U.S. federal judicial districts. Each U.S. attorney serves as the United States' chief federal c ...

and 18 U.S. Marshals

The United States Marshals Service (USMS) is a federal law enforcement agency in the United States. The USMS is a bureau within the U.S. Department of Justice, operating under the direction of the Attorney General, but serves as the enforceme ...

., 1985, at 22. Jefferson also displaced two district judges—Ray Greene Ray Greene may refer to:

* Ray Greene (politician) (1765–1849), United States senator from Rhode Island

* Ray Greene (American football) (1938–2022), American football coach

* Ray Greene (lacrosse) (1923–1987), American lacrosse player

* Raym ...

and Jacob Read

Jacob Read (1752 – July 17, 1816) was an American lawyer and politician from Charleston, South Carolina. He represented South Carolina in both the Continental Congress (1783–1785) and the United States Senate (1795–1801).

Biography

Read ...

—citing technical flaws in their appointments. Further, District Judge John Pickering John Pickering may refer to:

* John Pickering (dramatist), author of the play ''Horestes'' first published in 1567

* John Pickering (MP) (1585–1628), MP for Northamptonshire (UK Parliament constituency), Northamptonshire, 1626

* John Pickering (s ...

was impeached and removed from office on a party-line vote

A party-line vote in a deliberative assembly (such as a constituent assembly, parliament, or legislature) is a vote in which a substantial majority of members of a political party vote the same way (usually in opposition to the other political ...

., 1985, at 23. The following day, the House impeached Justice Samuel Chase

Samuel Chase (April 17, 1741 – June 19, 1811) was a Founding Father of the United States, a signatory to the Continental Association and United States Declaration of Independence as a representative of Maryland, and an Associate Justice of th ...

, but six Democratic-Republicans crossed party lines in the Senate to prevent his conviction by a single vote.

In ''Marbury'', the Supreme Court held that Madison's failure to deliver the commission to Marbury was illegal, but did not grant Marbury a writ of mandamus

(; ) is a judicial remedy in the form of an order from a court to any government, subordinate court, corporation, or public authority, to do (or forbear from doing) some specific act which that body is obliged under law to do (or refrain from ...

on the ground that § 13 of the Judiciary Act of 1789 was unconstitutional

Constitutionality is said to be the condition of acting in accordance with an applicable constitution; "Webster On Line" the status of a law, a procedure, or an act's accordance with the laws or set forth in the applicable constitution. When l ...

insofar as it authorized the Court to issue such writs under its original jurisdiction

In common law legal systems original jurisdiction of a court is the power to hear a case for the first time, as opposed to appellate jurisdiction, when a higher court has the power to review a lower court's decision.

India

In India, the Sup ...

. ''Stuart v. Laird

''Stuart v. Laird'', 5 U.S. (1 Cranch) 299 (1803), was a case decided by United States Supreme Court notably a week after its famous decision in '' Marbury v. Madison''.

''Stuart'' dealt with a judgment of a circuit judge whose position had bee ...

''—involving a civil judgment rendered by a circuit court constituted under the Midnight Judges Act and enforced by a circuit court constituted under the Judiciary Act of 1802—challenged the constitutionality both of abolishing the circuit judgeships and of requiring the Supreme Court justices to ride circuit. In a brief opinion, the Court rejected both challenges.

District of Columbia Organic Act of 1801

Both theUnited States Circuit Court of the District of Columbia

The United States Circuit Court of the District of Columbia (in case citations, C.C.D.C.) was a United States federal court which existed from 1801 to 1863. The court was created by the District of Columbia Organic Act of 1801.

History

The D.C. ci ...

and the D.C. justices of the peace

A justice of the peace (JP) is a judicial officer of a lower or ''puisne'' court, elected or appointed by means of a commission ( letters patent) to keep the peace. In past centuries the term commissioner of the peace was often used with the sa ...

were created on February 27, 1801 by the District of Columbia Organic Act of 1801

The District of Columbia Organic Act of 1801, officially An Act Concerning the District of Columbia (6th Congress, 2nd Sess., ch. 15, , February 27, 1801), is an organic act enacted by the United States Congress in accordance with Article 1, Sec ...

. Unlike its better-known predecessor, the Midnight Judges Act

The Midnight Judges Act (also known as the Judiciary Act of 1801; , and officially An act to provide for the more convenient organization of the Courts of the United States) represented an effort to solve an issue in the U.S. Supreme Court during t ...

, the Organic Act survived repeal by the Jeffersonian Congress. John G. Roberts, Jr., ''What Makes the D.C. Circuit Different?: A Historical View'', 92 375, 378 (2006).

D.C. justices of the peace

The D.C. justices of the peace were appointed by the President, in a number at his discretion, and confirmed by the Senate for five-year terms. A D.C. justice of the peace had jurisdiction over "all matters, civil and criminal, and in whatever relates to the conservation of the peace" within their county.District of Columbia Organic Act of 1801, § 11, 2 Stat. 103, 107. The District of Columbia was divided into two counties: Washington County, east of the

The D.C. justices of the peace were appointed by the President, in a number at his discretion, and confirmed by the Senate for five-year terms. A D.C. justice of the peace had jurisdiction over "all matters, civil and criminal, and in whatever relates to the conservation of the peace" within their county.District of Columbia Organic Act of 1801, § 11, 2 Stat. 103, 107. The District of Columbia was divided into two counties: Washington County, east of the Potomac River

The Potomac River () drains the Mid-Atlantic United States, flowing from the Potomac Highlands into Chesapeake Bay. It is long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map. Retrieved Augus ...

, and Alexandria County

Arlington County is a County (United States), county in the Virginia, Commonwealth of Virginia. The county is situated in Northern Virginia on the southwestern bank of the Potomac River directly across from the Washington, D.C., District of Co ...

, west of the Potomac. Justices of the peace were authorized to "inflict whipping, imprisonment, and fine as high as 500 pounds of tobacco" and to hear civil cases with an amount in controversy

Amount in controversy (sometimes called jurisdictional amount) is a term used in civil procedure to denote the amount at stake in a lawsuit, in particular in connection with a requirement that persons seeking to bring a lawsuit in a particular cour ...

up to $20.''More'', 7 U.S. at 167 (oral argument). One year after ''More'', in ''Ex parte Burford'' (1806), the Marshall Court's first original habeas case, the Court granted a writ of habeas corpus

''Habeas corpus'' (; from Medieval Latin, ) is a recourse in law through which a person can report an unlawful detention or imprisonment to a court and request that the court order the custodian of the person, usually a prison official, t ...

to a prisoner subjected to preventive detention

Preventive detention is an imprisonment that is putatively justified for non-punitive purposes, most often to prevent (further) criminal acts.

Types of preventive detention

There is no universally agreed definition of preventive detention, and mu ...

by the D.C. justices of the peace.

As to compensation, the Organic Act provided that justices of the peace "shall be entitled to receive for their services the fees allowed for like services by the laws herein before adopted and continued, in the eastern part of said district." A March 3, 1801 amendment to the Organic Act provided that: " e magistrates, to be appointed for the said district, shall be and they are hereby constituted a board of commissioners within their respective counties, and shall possess and exercise the same powers, perform the same duties, receive the same fees and , as the levy courts or commissioners of county for the state of Maryland possess, perform and receive . . . ."

On March 4, 1801, President John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Befor ...

's last day in office, Adams nominated and the Senate confirmed 20 D.C. justices of the peace for Washington County and 19 for Alexandria County.O'Fallon, 1993, at 43 & n.4. On March 16, President Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

issued 15 commissions to justices of the peace in Washington County, including 13 nominated by Adams, and 15 in Alexandria County, including 11 nominated by Adams; the remainder were of his own choosing. (Jefferson's list, submitted to the Senate on January 6, 1802, erroneously contained the name of John Laird, a confirmed Adams appointed who had not received a commission from Jefferson, instead of More.) The plaintiffs in ''Marbury v. Madison

''Marbury v. Madison'', 5 U.S. (1 Cranch) 137 (1803), was a List of landmark court decisions in the United States, landmark Supreme Court of the United States, U.S. Supreme Court case that established the principle of Judicial review in the Uni ...

'' (1803)—William Marbury

William Marbury (November 7, 1762 – March 13, 1835) was a highly successful American businessman and one of the "Midnight Judges" appointed by United States President John Adams the day before he left office. He was the plaintiff in the landmar ...

, Dennis Ramsay, Robert Townsend Hooe, and William Harper—were among the confirmed Adams nominees not commissioned.

On May 3, 1802, Congress eliminated both the fees for justice of the peace services, except travel expenses, authorized by the Organic Act and fees associated with the justices of the peace's role on the board of commissioners. These two sources represented the entirety of their compensation.O'Fallon, 1993, at 52.

D.C. circuit court

The three-judgeUnited States Circuit Court of the District of Columbia

The United States Circuit Court of the District of Columbia (in case citations, C.C.D.C.) was a United States federal court which existed from 1801 to 1863. The court was created by the District of Columbia Organic Act of 1801.

History

The D.C. ci ...

was populated by its own judges, rather than by a mixture of district judges and circuit riding Supreme Court justices like the other circuit courts. The D.C. circuit court had jurisdiction over crimes committed within the district. With regard to appeals from the D.C. circuit court, the Organic Act provided:

: y final judgment, order or decree in said circuit court, wherein the matter in dispute, exclusive of costs, shall exceed the value of one hundred dollars, may be re-examined and reversed or affirmed in the supreme court of the United States, by writ of error or appeal, which shall be prosecuted in the same manner, under the same regulations, and the same proceedings shall be had therein, as is or shall be provided in the case of writs of error on judgments, or appeals upon orders or decrees, rendered in the circuit court of the United States.

The provision to which the Organic Act referred, that for writs of error from the circuit courts to the Supreme Court in the Judiciary Act of 1789

The Judiciary Act of 1789 (ch. 20, ) was a United States federal statute enacted on September 24, 1789, during the first session of the First United States Congress. It established the federal judiciary of the United States. Article III, Secti ...

, provided:

:And upon a like process s a writ of error from the district court to the circuit court may final judgments and decrees in civil actions, and suits in equity in a circuit court, brought there by original process, or removed there from courts of the several States, or removed there by appeal from a district court where the matter in dispute exceeds the sum or value of two thousand dollars, exclusive of costs, be re-examined and reversed or affirmed in the Supreme Court, the citation being in such case signed by a judge of such circuit court, or justice of the Supreme Court, and the adverse party having at least thirty days’ notice.Judiciary Act of 1789

The Judiciary Act of 1789 (ch. 20, ) was a United States federal statute enacted on September 24, 1789, during the first session of the First United States Congress. It established the federal judiciary of the United States. Article III, Secti ...

, § 22, 1 Stat. 73, 84.

Unlike the appellate provision of the Judiciary Act of 1789, the appellate provision of the act of February 27, 1801 was not explicitly limited to civil cases (except insofar as it incorporated the former by reference). Further, because the D.C. circuit court was not constituted within the framework of the Judiciary Act of 1802 The Judiciary Act of 1802 () was a Federal statute, enacted on April 29, 1802, to reorganize the federal court system. It restored some elements of the Judiciary Act of 1801, which had been adopted by the Federalist majority in the previous Congres ...

, appeals to the Supreme Court by way of certificates of division could not issue. After ''More'', the Marshall Court heard six appeals from the D.C. circuit court via original habeas.

Criminal appeals

The availability of criminal appeals to the Supreme Court by means of writs of error from the circuit courts was perhaps an open question prior to ''More''. In

The availability of criminal appeals to the Supreme Court by means of writs of error from the circuit courts was perhaps an open question prior to ''More''. In England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

, the writ of error was available as of right in misdemeanor

A misdemeanor (American English, spelled misdemeanour elsewhere) is any "lesser" criminal act in some common law legal systems. Misdemeanors are generally punished less severely than more serious felonies, but theoretically more so than adm ...

cases, but, in felony

A felony is traditionally considered a crime of high seriousness, whereas a misdemeanor is regarded as less serious. The term "felony" originated from English common law (from the French medieval word "félonie") to describe an offense that resu ...

cases, required the express consent of the prosecutor.

The legislative history of the Judiciary Act of 1789

The Judiciary Act of 1789 (ch. 20, ) was a United States federal statute enacted on September 24, 1789, during the first session of the First United States Congress. It established the federal judiciary of the United States. Article III, Secti ...

reveals little consideration of criminal appeals. Caleb Strong

Caleb Strong (January 9, 1745 – November 7, 1819) was an American lawyer, politician, and Founding Father who served as the sixth and tenth governor of Massachusetts between 1800 and 1807, and again from 1812 until 1816. He assisted in draft ...

, a Senator at the time of its drafting, described § 22 of that act as follows: "Writs of Error from the Circuit to the Supr. Court in all Causes not criminal of which the Circuit Court has original Cognizance and the Matter in Dispute does not exceed 2000 Dolrs." Senator (and future Supreme Court justice) William Paterson noticed the lack of provision for criminal appeals in preliminary notes and a draft outline of a speech he gave on June 23, 1789.Rossman, 1990, at 557. According to Rossman, Paterson may have viewed the inability of the government to appeal (to a court in the nation's capitol) as a "protection for ordinary citizens." The issue of criminal appeals was not mentioned in the House debates.

Shortly after the Judiciary Act of 1789 took effect, Attorney General Edmund Randolph

Edmund Jennings Randolph (August 10, 1753 September 12, 1813) was a Founding Father of the United States, attorney, and the 7th Governor of Virginia. As a delegate from Virginia, he attended the Constitutional Convention and helped to create ...

proposed, in a report to the House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entitles. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often c ...

, a criminal appeal similar to that in England: a writ of error as of right in non-capital cases, and no writs of error in capital cases.Rossman, 1990, at 557 n.184. Randolph's report was referred to the Committee of the Whole

A committee of the whole is a meeting of a legislative or deliberative assembly using procedural rules that are based on those of a committee, except that in this case the committee includes all members of the assembly. As with other (standing) c ...

, which took no action.

Prior to Marshall's tenure, the Supreme Court had heard only two criminal cases—both by prerogative writ

A prerogative writ is a historic term for a writ (official order) that directs the behavior of another arm of government, such as an agency, official, or other court. It was originally available only to the Crown under English law, and reflected ...

. First, in '' United States v. Hamilton'' (1795), the Court granted bail to a capital defendant—as it was authorized to do by § 33 of the Judiciary Act of 1789 and § 4 of the Judiciary Act of 1793 The Judiciary Act of 1793 (ch. 22 of the Acts of the 2nd United States Congress, 2nd Session, ) is a United States federal statute, enacted on March 2, 1793. It established a number of regulations related to court procedures.

The Judiciary Act of ...

. The greater portion of the decision was dedicated to the Court's refusal to order the case tried by a special circuit court, as was provided for by § 3 of the Judiciary Act of 1793. In '' Ex parte Bollman'' (1807), the Court explained that its jurisdiction in ''Hamilton'' could only have been exercised via original habeas under § 14 of the Judiciary Act of 1789. Second, in '' United States v. Lawrence'' (1795), the Court declined to issue a writ of mandamus

(; ) is a judicial remedy in the form of an order from a court to any government, subordinate court, corporation, or public authority, to do (or forbear from doing) some specific act which that body is obliged under law to do (or refrain from ...

to compel a district judge to order the arrest of a deserter of the French navy. In one criminal trial, ''United States v. Callender'' (C.C.D. Va. 1800), Justice Samuel Chase

Samuel Chase (April 17, 1741 – June 19, 1811) was a Founding Father of the United States, a signatory to the Continental Association and United States Declaration of Independence as a representative of Maryland, and an Associate Justice of th ...

(who expressed no dissent in ''More'') wrote:

: I am not right, it is an error in judgment, and you can state the proceedings on the record so as to show any error, and I shall be the first man to grant you the benefit a new trial by granting you a writ of error in the supreme court.

In '' United States v. Simms'' (1803), the Court heard a writ of error, brought by the United States, on the merits from a criminal case in the D.C. circuit court. ''Simms'' was the first such case, and after ''Simms'', the next criminal writ of error heard by the Court was ''More''.Rossman, 1990, at 523. U.S. Attorney for the District of Columbia

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

John T. Mason argued both ''Simms'' and ''More''.

Indictments

Benjamin More was one of two of D.C. justices of peace in

Benjamin More was one of two of D.C. justices of peace in Alexandria County

Arlington County is a County (United States), county in the Virginia, Commonwealth of Virginia. The county is situated in Northern Virginia on the southwestern bank of the Potomac River directly across from the Washington, D.C., District of Co ...

of Jefferson's own choosing, receiving an interim appointment.O'Fallon, 1993, at 43. Jefferson proceeded to nominate More for a full five-year term, and the Senate confirmed More on April 27, 1802.O'Fallon, 1993, at 48. According to O'Fallon, "More appears to have been a man of moderate Jeffersonian sentiments and attachments, who nonetheless joined in a Federalist defense of judicial independence."O'Fallon, 1993, at 45. He was "an unlikely character for the lead role in a Federalist attack on Jeffersonian principles." O'Fallon hypothesizes that More's case was intended as a test case

In software engineering, a test case is a specification of the inputs, execution conditions, testing procedure, and expected results that define a single test to be executed to achieve a particular software testing objective, such as to exercise ...

by all parties involved. "''More'' has all the markings of a trumped-up case, manufactured to present the Supreme Court with the issues of principle raised by the repeal, without the embarrassment of direct conflict with the Executive."

More was indicted by the Grand Inquest for the County of Washington, during its July term, for taking unlawful fees for his services as a justice of the peace.''More'', 7 U.S. at 172. The indictment charged More with having taken the fees on July 17 and 24. A capias

An arrest warrant is a warrant issued by a judge or magistrate on behalf of the state, which authorizes the arrest and detention of an individual, or the search and seizure of an individual's property.

Canada

Arrest warrants are issued by a ju ...

, returnable at the December 1802 term, was issued. The members of the Inquest included five other D.C. justices of the peace: Daniel Carrol, Daniel Reintzell, Joseph Sprigg Belt, Thomas Corcoran, and Anthony Reintzell.O'Fallon, 1993, at 48 n.28. Another member of the Inquest was Thomas Beall, a confirmed Adams appointee who had not received a commission from Jefferson.

More was indicted a second time at the December term for conduct on December 10, 1802.O'Fallon, 1993, at 49. More demured, and the case was continued until the July 1803 term. Only the latter indictment was mentioned in the United States Reports

The ''United States Reports'' () are the official record ( law reports) of the Supreme Court of the United States. They include rulings, orders, case tables (list of every case decided), in alphabetical order both by the name of the petitioner ...

.

More's demurrer

A demurrer is a pleading in a lawsuit that objects to or challenges a pleading filed by an opposing party. The word ''demur'' means "to object"; a ''demurrer'' is the document that makes the objection. Lawyers informally define a demurrer as a de ...

was opposed by U.S. Attorney Mason, a Jefferson appointee. Mason argued that the D.C. justices of the peace were Article I judges established pursuant to Congress's enumerated power

The enumerated powers (also called expressed powers, explicit powers or delegated powers) of the United States Congress are the powers granted to the federal government of the United States by the United States Constitution. Most of these powers ar ...

over the District of Columbia in Article One of the United States Constitution

Article One of the United States Constitution establishes the legislative branch of the Federal government of the United States, federal government, the United States Congress. Under Article One, Congress is a bicameral legislature consisting of ...

. Article One provides that Congress shall have power " exercise exclusive Legislation in all Cases whatsoever, over such District (not exceeding ten Miles square) as may, by Cession of particular States, and the Acceptance of Congress, become the Seat of the Government of the United States." Mason advanced a broad view that Congress's power over the District of Columbia was not limited any other constitutional provision. In support of his argument that the justices of the peace were not Article III judges

Federal tribunals in the United States are those tribunals established by the federal government of the United States for the purpose of resolving disputes involving or arising under federal laws, including questions about the constitutionality ...

, Mason argued that their jurisdiction was broader than that permitted by Article III.

According to O'Fallon, there were additional indicia—not cited by either party—that the justices of the peace were not Article III judges.O'Fallon, 1993, at 50–51. For example, the Organic Act authorized the President to appoint as many justices of the peace as he "shall from time to time think expedient." This was a broad delegation to the President of Congress's power " constitute Tribunals inferior to the supreme Court."

More was not indicted under any criminal statue passed by Congress. Rather, his was "an indictment at common law . . . for having, under colour of his office, exacted and taken an illegal fee."''More'', 7 U.S. at 160 n.* (C.C.D.C. 1803) (Kilty, C.J., dissenting). The Organic Act provided that the laws of Maryland and Virginia would continue in force in the portions of the district ceded from those states. Since More was a justice of the peace for Alexandria County, the common law of Virginia would have applied.

Dismissal

The D.C. circuit court judges hearing the

The D.C. circuit court judges hearing the demurrer

A demurrer is a pleading in a lawsuit that objects to or challenges a pleading filed by an opposing party. The word ''demur'' means "to object"; a ''demurrer'' is the document that makes the objection. Lawyers informally define a demurrer as a de ...

were Chief Judge William Kilty and assistant judges William Cranch

William Cranch (July 17, 1769 – September 1, 1855) was a United States federal judge, United States circuit judge and chief judge of the United States Circuit Court of the District of Columbia. A staunch Federalist Party, Federalist and nephe ...

and James Markham Marshall

James Markham Marshall (March 12, 1764 – April 26, 1848) was an American lawyer, Revolutionary War soldier and planter who briefly served as United States circuit judge of the United States Circuit Court of the District of Columbia .

Early l ...

(Chief Justice John Marshall's brother). Cranch and Marshall were Adams appointees; Kilty was a Jefferson appointee. Cranch, also the reporter of decisions for the Supreme Court, included the D.C. circuit court opinions in the margin of his report of the Supreme Court's decision in ''More''.

Majority

Cranch, joined by Marshall, sustained More's demurrer based on theCompensation Clause

Article Three of the United States Constitution establishes the judicial branch of the U.S. federal government. Under Article Three, the judicial branch consists of the Supreme Court of the United States, as well as lower courts created by Congr ...

of Article Three of the United States Constitution

Article Three of the United States Constitution establishes the judicial branch of the U.S. federal government. Under Article Three, the judicial branch consists of the Supreme Court of the United States, as well as lower courts created by Congres ...

.''More'', 7 U.S. at 160 n.* (C.C.D.C. 1803) (Cranch, J., joined by Marshall, J.). That clause provides: "The Judges, both of the supreme and inferior Courts . . . shall, at stated Times, receive for their Services a Compensation which shall not be diminished during their Continuance in Office." art. III, § 1 (emphasis added).

Cranch held that Congress's power over the federal district was limited by the remainder of the Constitution. In response to Mason's argument for unfettered power, Cranch replied: " is is a doctrine to which I can never assent. Can it be said, that congress may pass a bill of attainder

In English criminal law, attainder or attinctura was the metaphorical "stain" or "corruption of blood" which arose from being condemned for a serious capital crime (felony or treason). It entailed losing not only one's life, property and hereditar ...

for the district of Columbia? That congress may pass laws ex post facto in the district, or order soldiers to be quartered upon us in a time of peace, or make our ports free ports of entry, or lay duties upon our exports, or take away the right of trial by jury, in criminal prosecutions?"

Cranch held that More was an Article III judge

Federal tribunals in the United States are those tribunals established by the federal government of the United States for the purpose of resolving disputes involving or arising under federal laws, including questions about the constitutionality ...

sitting on a "Tribunal inferior to the supreme Court." In response to the argument that his jurisdiction exceeded Article Three, Cranch replied that: "The causes of which they have cognizance, are causes arising under the laws of the United States, and, therefore, the power of trying them, is part of the judicial power . . . ." In response to the argument that the fees would never have been paid at a "time Stated," Cranch replied that: " may, perhaps, be a compliance with the clause of the constitution, which requires that it shall be receivable at stated times, to say that it shall be paid when the service is rendered. And, we are rather to incline to this construction, than to suppose the command of the constitution to have been disobeyed." Further, Cranch dodged the question of whether a five-year term was consistent with the Good Behavior Clause

Article Three of the United States Constitution establishes the judicial branch of the U.S. federal government. Under Article Three, the judicial branch consists of the Supreme Court of the United States, as well as lower courts created by Congr ...

. "It is unnecessary in this cause to decide the question, whether, as such, he holds his office during good behaviour . . . ."

Cranch stopped short of declaring the statute unconstitutional. He merely interpreted it aprospective

holding that it "cannot affect that justice of the peace during his continuance in office; whatever effect it may have upon those justices who have been appointed to office since the passing of the act." Contemporary media accounts reported that the circuit court had held that fee-elimination provision of the May 23, 1802 act unconstitutional, rather than interpreting it as prospective.O'Fallon, 1993, at 51 n.42. According to O'Fallon, this is evidence that Cranch's published opinion (as reported by himself) may have differed from his oral opinion.

Dissent

Chief Judge Kilty's dissent noted the recent confirmation of the principle ofjudicial review

Judicial review is a process under which executive, legislative and administrative actions are subject to review by the judiciary. A court with authority for judicial review may invalidate laws, acts and governmental actions that are incompat ...

in ''Marbury v. Madison

''Marbury v. Madison'', 5 U.S. (1 Cranch) 137 (1803), was a List of landmark court decisions in the United States, landmark Supreme Court of the United States, U.S. Supreme Court case that established the principle of Judicial review in the Uni ...

''. "According to the course which has been pursued by the supreme court, it appears unnecessary to say any thing about the power of a court to examine into the constitutionality of a law . . . ." Instead, Kilty proceeded by "taking the power for granted." But, Kilty noted, " testing an act of the legislature by the constitution, nothing less than the positive provisions of the latter can be resorted to . . . ."

Kilty briefly argued that More was not an Article III judge

Federal tribunals in the United States are those tribunals established by the federal government of the United States for the purpose of resolving disputes involving or arising under federal laws, including questions about the constitutionality ...

and that the fees in question were not compensation received at "times Stated." But, the bulk of Kilty's dissent was devoted to the argument that Congress's power over the federal district was broad. He argued that "the district of Columbia, though belonging to the United States, and within their compass, is not, like a state, a component part, and that the provisions of the constitution, which are applicable particularly to the relative situation of the United States and the several states, are not applicable to this district." " en congress, in exercising exclusive legislation over this territory, enact laws to give or to take away the fees of the justices of the peace, such laws cannot be tested by a provision in the constitution, evidently applicable to the judicial power of the whole United States, and containing restrictions which cannot, in their nature, affect the situation of the justices, or the nature of the compensation."

Yet, Kilty did not fully accept Mason's argument that Congress's power over the district was unlimited. He argued that the word "exclusive" meant only "free from the power exercised by the several states" and that "the legislative power to be exercised by congress may still be subject to the general restraints contained in the constitution." He admitted that, even within the federal district, Congress was

:restrained from suspending the writ of habeas corpus, unless in the cases allowed; from passing (within and for the district) a bill of attainder, or ex post facto law; from laying therein a capitation tax; from granting therein any title of nobility; from making therein a law respecting the establishment of religion, or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; and from quartering soldiers therein, contrary to the third amendment.

Oral argument

Mason argued the appeal of the United States before the Supreme Court. Samuel Jones argued for More.Merits

Jones cited ''Marbury v. Madison

''Marbury v. Madison'', 5 U.S. (1 Cranch) 137 (1803), was a List of landmark court decisions in the United States, landmark Supreme Court of the United States, U.S. Supreme Court case that established the principle of Judicial review in the Uni ...

'' for the proposition that a D.C. justice of the peace does not serve merely at the pleasure of the president. According to O'Fallon, due to the President's power to remove most appointees from office, this could only have been a reference to the Good Behavior Clause

Article Three of the United States Constitution establishes the judicial branch of the U.S. federal government. Under Article Three, the judicial branch consists of the Supreme Court of the United States, as well as lower courts created by Congr ...

of Article Three.O'Fallon, 1993, at 51 n.40. That clause provides that "Judges, both of the supreme and inferior Courts, shall hold their Offices during good Behavior." Mason countered that ''Marbury'' only held that justices of the peace were entitled to hold their offices for five years of good behavior.

Mason again pressed his argument that Congress's power of the federal district was unlimited:

:The constitution does not apply to this case. The constitution is a compact between the people of the United States in their individual capacity, and the states in their political capacity. Unfortunately for the citizens of Columbia, they are not in either of these capacities. . . . Congress are under ''no controul'' in legislating for the district of Columbia. Their power, in this respect, is ''unlimited''.

Marson also argued that More was not an Article III judge

Federal tribunals in the United States are those tribunals established by the federal government of the United States for the purpose of resolving disputes involving or arising under federal laws, including questions about the constitutionality ...

because "the judicial power exercised in the district of Columbia, extends to other cases han those enumerated in Article III and, therefore, is not the judicial power of the United States."''More'', 7 U.S. at 168 (oral argument). "It is a power derived from the power given to congress to ''legislate'' exclusively in all cases whatsoever over the district."

Jurisdiction

On February 13,

On February 13, sua sponte

In law, ''sua sponte'' (Latin: "of his, her, its or their own accord") or ''suo motu'' ("on its own motion") describes an act of authority taken without formal prompting from another party. The term is usually applied to actions by a judge taken wi ...

, Chief Justice Marshall raised his doubts to the Court's jurisdiction to entertain criminal appeals.''More'', 7 U.S. at 169 (oral argument). Argument on this question commenced on February 22. Mason argued in favor of jurisdiction. No argument from More's counsel on this issue was reported, "although it was typical for the reporter to summarize the arguments on both sides."

Mason acknowledged that, under '' Clarke v. Bazadone'' (1803), the Supreme Court's appellate jurisdiction required an affirmative grant by Congress.''More'', 7 U.S. at 170 (oral argument). Mason argued that such a grant was found in § 14 of the Judiciary Act of 1789

The Judiciary Act of 1789 (ch. 20, ) was a United States federal statute enacted on September 24, 1789, during the first session of the First United States Congress. It established the federal judiciary of the United States. Article III, Secti ...

(known as the All Writs Act

The All Writs Act is a United States federal statute, codified at , which authorizes the United States federal courts to "issue all writs necessary or appropriate in aid of their respective jurisdictions and agreeable to the usages and principles ...

), which authorized the Supreme Court to "issue writs of ''scire facias

In English law, a writ of ''scire facias'' (Latin, meaning literally "make known") was a writ founded upon some judicial record directing the sheriff to make the record known to a specified party, and requiring the defendant to show cause why th ...

'', ''habeas corpus

''Habeas corpus'' (; from Medieval Latin, ) is a recourse in law through which a person can report an unlawful detention or imprisonment to a court and request that the court order the custodian of the person, usually a prison official, t ...

'', and all other writs, not specially provided for by statute, which may be necessary for the exercise of tsjurisdiction, and agreeable to the principles and usages of law." Mason's argument based on the All Writs Act was not necessarily limited to the D.C. circuit court. Said Mason:

:There is no reason why the writ of error should be confined to civil cases. A man's life, his liberty, and his good name, are as dear to him as his property; and inferior courts are as liable to err in one case as in the other. There is nothing in the nature of the cases which should make a difference; nor is it a novel doctrine that a writ of error should lie in a criminal case. They have been frequent in that country from which we have drawn almost all our forms of judicial proceedings.

Chief Justice Marshall replied that, if Congress had made no provision for appeals of any kind to the Supreme Court, "your argument would be irresistible." But, Marshall countered, under the Exceptions Clause

Article Three of the United States Constitution establishes the judicial branch of the U.S. federal government. Under Article Three, the judicial branch consists of the Supreme Court of the United States, as well as lower courts created by Congres ...

, when Congress "has said in what cases a writ of error or appeal shall lie, an exception of all other cases is implied."''More'', 7 U.S. at 171 (oral argument). The Exceptions Clause provides that " all ases other than those in which the Supreme Court has original jurisdiction the supreme Court shall have appellate Jurisdiction, both as to Law and Fact, with such Exceptions, and under such Regulations as the Congress shall make."

Mason replied, first, that the Exceptions Clause did not apply to the federal district, and second, that Organic Act differed from the Judiciary Act of 1789 by referring to "any final judgment, order, or decree," rather than explicitly limiting appeals to "civil cases." Mason suggested that the references to the amount in controversy

Amount in controversy (sometimes called jurisdictional amount) is a term used in civil procedure to denote the amount at stake in a lawsuit, in particular in connection with a requirement that persons seeking to bring a lawsuit in a particular cour ...

could refer to criminal fines as well as civil judgments. Finally, Mason pointed out that, just two years earlier, in '' United States v. Simms'' (1803), the Court had reached the merits in a criminal appeal from the same court.''More'', 7 U.S. at 172. Mason himself had argued ''Simms'', and Marshall himself had authored the opinion.

In response to the last point, Marshall replied that: "No question was made, in that case, as to the jurisdiction. It passed ''sub silentio'', and the court does not consider itself as bound by that case." Mason retorted: "But the traverser imms

The Institute for Marine Mammal Studies ("IMMS") is a research organization located in Gulfport, Mississippi and dedicated to education, conservation, and research on marine mammals in the wild and in captivity. It was founded in 1984 as a researc ...

had able counsel, who did not think proper to make the objection."

Opinion

On March 2, 1805, writing for a unanimous Court, Chief Justice

On March 2, 1805, writing for a unanimous Court, Chief Justice John Marshall

John Marshall (September 24, 1755July 6, 1835) was an American politician and lawyer who served as the fourth Chief Justice of the United States from 1801 until his death in 1835. He remains the longest-serving chief justice and fourth-longes ...

dismissed the writ of error for want of jurisdiction. Justice Johnson was absent from the opinion announcement.

Marshall held that the partial statutory grant of appellate jurisdiction to the Court operated as an exercise of Congress's power under the Exceptions Clause

Article Three of the United States Constitution establishes the judicial branch of the U.S. federal government. Under Article Three, the judicial branch consists of the Supreme Court of the United States, as well as lower courts created by Congres ...

to limit the jurisdiction of the Court in all other cases. Marshall noted that "it has never been supposed, that a decision of a circuit court could be reviewed, unless the matter in dispute should exceed the value of 2,000 dollars."''More'', 7 U.S. at 173. Thus, Marshall interpreted the $2000 amount in controversy

Amount in controversy (sometimes called jurisdictional amount) is a term used in civil procedure to denote the amount at stake in a lawsuit, in particular in connection with a requirement that persons seeking to bring a lawsuit in a particular cour ...

requirement of § 22 of the Judiciary Act of 1789

The Judiciary Act of 1789 (ch. 20, ) was a United States federal statute enacted on September 24, 1789, during the first session of the First United States Congress. It established the federal judiciary of the United States. Article III, Secti ...

as applying to the entire section, rather than only the last antecedent.

Marshall rejected the argument that the Organic Act authorized criminal appellate jurisdiction. He interpreted the grant, in light of its $100 amount in controversy requirement, as "confined to civil cases." "The words, 'matter in dispute,' seem appropriated to civil cases, where the subject in contest has a value beyond the sum mentioned in the act. But, in criminal cases, the question is the guilt or innocence of the accused. And although he may be fined upwards of 100 dollars, yet that is, in the eye of the law, a punishment for the offence committed, and not the particular object of the suit."

A final footnote refers to '' United States v. La Vengeance'' (1796), "where it seems to be admitted, that in criminal cases the judgment of the inferior court is final." ''La Vengeance'' was an admiralty libel case. There, at oral argument, Attorney General Charles Lee argued, in the alternative, that the case was a "criminal cause" and therefore "should never have been removed to the Circuit Court, the judgment of the District Court being final in criminal causes." The Court summarily rejected Lee's argument: "we are unanimously of opinion, that it is a civil cause: It is a process of the nature of a libel in rem

''In rem'' jurisdiction ("power about or against 'the thing) is a legal term describing the power a court may exercise over property (either real or personal) or a "status" against a person over whom the court does not have ''in personam'' jurisdi ...

; and does not, in any degree, touch the persons of the offender."

Aftermath

After ''More'', no writs of error issued from federal criminal trials in the circuit courts for 84 years. In 1889, Congress created a right of appeal by writ of error in capital cases. In 1891, theJudiciary Act of 1891

The Judiciary Act of 1891 ({{USStat, 26, 826), also known as the Evarts Act after its primary sponsor, Senator William M. Evarts, created the United States courts of appeals and reassigned the jurisdiction of most routine appeals from the United S ...

(the "Evarts Act") extended this right to other serious crimes. The Judicial Code of 1911

The Judicial Code of 1911 () abolished the United States circuit courts and transferred their trial jurisdiction to the U.S. district courts.

In 1911, the United States Congress created a single code encompassing all statutes related to the judici ...

abolished the circuit courts and placed original jurisdiction

In common law legal systems original jurisdiction of a court is the power to hear a case for the first time, as opposed to appellate jurisdiction, when a higher court has the power to review a lower court's decision.

India

In India, the Sup ...

for the trial of all federal crimes in the district courts. Appeal to the courts of appeals by writs of error was provided for all "final decisions," in civil and criminal cases alike. Appeals to the Supreme Court were permitted directly from the district courts by writ of error, from the courts of appeals on certified question In the law of the United States, a certified question is a formal request by one court from another court, usually but not always in another jurisdiction, for an opinion on a question of law.

These cases typically arise when the court before whic ...

s, and by petition for certiorari. Without reported discussion of the jurisdictional issue, the Court did hear writs of error from criminal cases removed to the circuit courts. (Recall that the Judiciary Act of 1789

The Judiciary Act of 1789 (ch. 20, ) was a United States federal statute enacted on September 24, 1789, during the first session of the First United States Congress. It established the federal judiciary of the United States. Article III, Secti ...

explicitly authorized appeals in removal cases.)

The Supreme Court had other, limited sources of appellate jurisdiction

A court of appeals, also called a court of appeal, appellate court, appeal court, court of second instance or second instance court, is any court of law that is empowered to hear an appeal of a trial court or other lower tribunal. In much of t ...

in criminal cases. The Court could hear criminal appeals from the state courts by writ of error, as authorized by the Judiciary Act of 1789. The Court could hear federal criminal appeals by certificate of division

A certificate of division was a source of appellate jurisdiction from the circuit courts to the Supreme Court of the United States from 1802 to 1911. Created by the Judiciary Act of 1802, the certification procedure was available only where the c ...

, as authorized by the Judiciary Act of 1802 The Judiciary Act of 1802 () was a Federal statute, enacted on April 29, 1802, to reorganize the federal court system. It restored some elements of the Judiciary Act of 1801, which had been adopted by the Federalist majority in the previous Congres ...

, original habeas petition, as authorized by the Judiciary Act of 1789, and mandamus

(; ) is a judicial remedy in the form of an order from a court to any government, subordinate court, corporation, or public authority, to do (or forbear from doing) some specific act which that body is obliged under law to do (or refrain from ...

, as authorized by the same act. Between 1867 and 1868, and after 1885, the Court had jurisdiction to hear writs of error from habeas petitions (a civil action) in the circuit courts. Beginning in 1850, the Court also entertained such appeals from the territorial courts. Attempts to utilize other prerogative writ

A prerogative writ is a historic term for a writ (official order) that directs the behavior of another arm of government, such as an agency, official, or other court. It was originally available only to the Crown under English law, and reflected ...

s as sources of jurisdiction were unsuccessful.

Analysis

''More'' had received far less scholarly attention than ''Marbury''.O'Fallon, 1993, at 44. "The timing and the ground of decision may explain why historians of the battle over repeal have ignored ''More''."James M. O'Fallon, Marbury, 44 219, 241 n.72 (1992). "In a doctrinal summary of constitutional law, More stands only for the proposition that an affirmative grant ofappellate jurisdiction

A court of appeals, also called a court of appeal, appellate court, appeal court, court of second instance or second instance court, is any court of law that is empowered to hear an appeal of a trial court or other lower tribunal. In much of t ...

by Congress carries with it an implicit negative of jurisdiction within the constitutional description but not mentioned in the grant."

According to O'Fallon, "''More'' may have been part of a Federalist strategy to get the Court to intervene in the political struggle over the judiciary." Given that Justice Samuel Chase

Samuel Chase (April 17, 1741 – June 19, 1811) was a Founding Father of the United States, a signatory to the Continental Association and United States Declaration of Independence as a representative of Maryland, and an Associate Justice of th ...

was acquitted by the Senate in his impeachment case on March 1, 1805, the day before the release of the ''More'' decision, " e can imagine John Marshall passing a sigh of relief as he handed down the judgment in ''More''." " e dismissal of ''More'' marked the end of Federalist efforts to obtain a Supreme Court ruling, directly or by implication, that the repeal of the 1801 Judiciary Act was unconstitutional. "''More'' is of a piece with ''Marbury'' and ''Stuart v. Laird

''Stuart v. Laird'', 5 U.S. (1 Cranch) 299 (1803), was a case decided by United States Supreme Court notably a week after its famous decision in '' Marbury v. Madison''.

''Stuart'' dealt with a judgment of a circuit judge whose position had bee ...

'' in its avoidance of an opportunity for an open clash with political critics of the courts. It further shares with ''Marbury'' the characteristic of declining an exercise of jurisdiction that the Court found to be unwarranted."O'Fallon, 1993, at 56. O'Fallon argues:

:Rather than seize the opportunity presented by ''More'', John Marshall ducked. . . . Without questioning the soundness or propriety of Marshall's decision, it is worth noting that the Court had previously entertained criminal appeals from the district without raising any such jurisdictional problem. One might reasonably wonder if the Court wanted to avoid a decision on the merits. By March of 1805, the repeal question had lost its political immediacy, and the impeachment strategy of the Jeffersonians had faltered. There was little to be gained in reopening the sores of the repeal battle. And Marshall may have felt that he had had his say on the critical matters of principle with his opinion in ''Marbury''.

Notes

References

*Dwight Henderson, (1985). *James M. O'Fallon, ''The Case of Benjamin More: A Lost Episode in the Struggle over Repeal of the 1801 Judiciary Act'', 11 43 (1993). * *David Rossman, ''"Were There No Review": The History of Review in American Criminal Courts'', 81 518 (1990).External links

* {{USArticleIII United States Constitution Article Three case law United States Supreme Court cases United States Supreme Court cases of the Marshall Court 1805 in United States case law Exceptions Clause case law Good Behavior Clause case law Legal history of the District of Columbia Criminal cases in the Marshall Court