United States and state-sponsored terrorism on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The

Starting in 1961 the U.S. government, through the

Starting in 1961 the U.S. government, through the

"The Posada File: Part II."

National Security Archive. He was the head of

Luis Posada Carriles, a former CIA agent who has been designated by scholars and journalists as a terrorist, also came into contact with Castro during his student days, but fled Cuba after the 1959 revolution, and helped organize the failed

Luis Posada Carriles, a former CIA agent who has been designated by scholars and journalists as a terrorist, also came into contact with Castro during his student days, but fled Cuba after the 1959 revolution, and helped organize the failed

The first Colombian paramilitary groups were organized by the Colombian government following recommendations made by U.S. military counterinsurgency advisers who were sent to Colombia in the early 1960s during the

The first Colombian paramilitary groups were organized by the Colombian government following recommendations made by U.S. military counterinsurgency advisers who were sent to Colombia in the early 1960s during the

"III: The Intelligence Reorganization"

Paramilitary violence and terrorism there was principally targeted to peasants, unionists, indigenous people, human rights workers, teachers and left-wing political activists or their supporters.

"Appendix A: Colombian Armed Forces Directive No. 200-05/91"

"Conclusions and Recommendations"

As an example of increased violence and "dirty war" tactics, Human Rights Watch cited a partnership between the Colombian Navy and the MAS, in

p. 159

/ref>

, ''National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 243'',

p. 88

/ref> The Calí cartel provided $50 million for weapons, informants, and assassins, with in hope of wiping out their primary rivals in the cocaine business.Kirk, 2003: pp. 156–158 Both Colombian and U.S. government agencies (including the DEA, CIA and State Department) provided intelligence to Los Pepes. The

Pepes Project

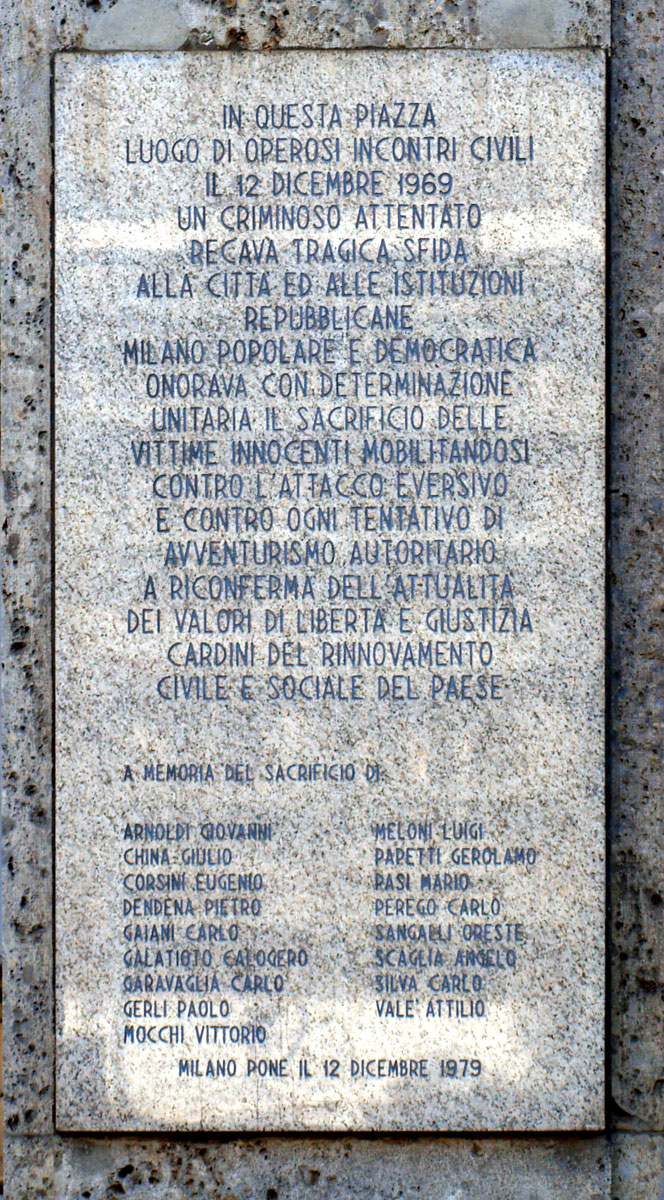

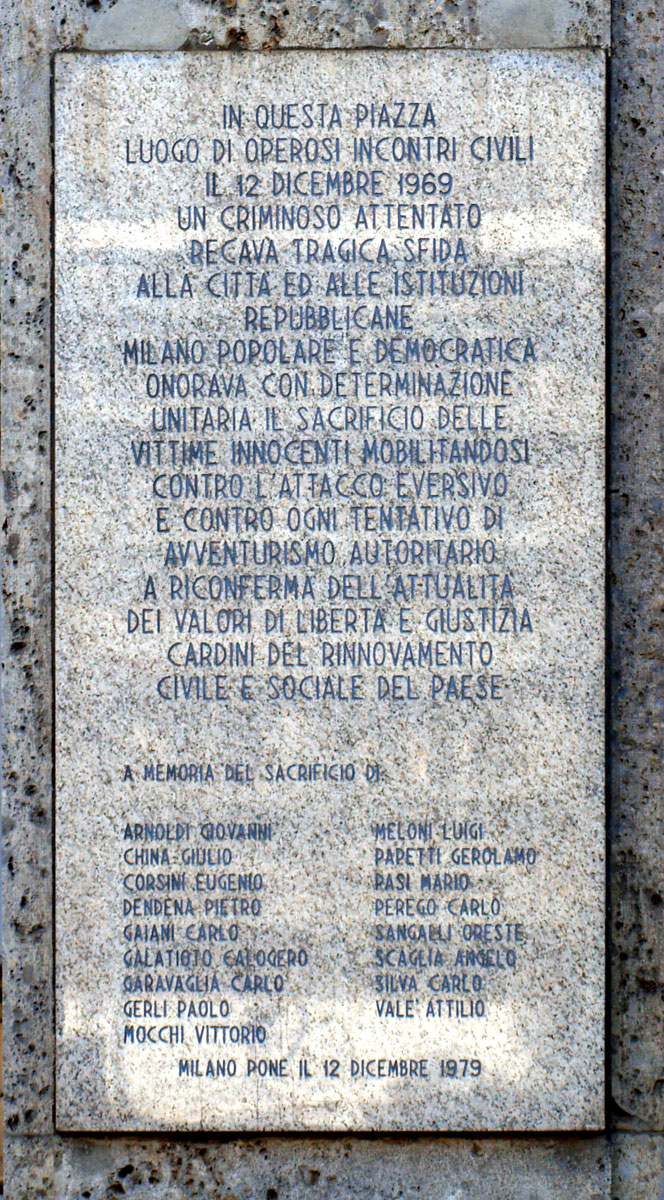

The Piazza Fontana Bombing was a terrorist attack that occurred on December 12, 1969 at 16:37, when a bomb exploded at the headquarters of

The Piazza Fontana Bombing was a terrorist attack that occurred on December 12, 1969 at 16:37, when a bomb exploded at the headquarters of

obituary by Philip Willan, in ''

In 1979, the

In 1979, the

In fiscal year 1984, the U.S. Congress approved $24 million in aid to the contras. However, the Reagan administration lost a lot of support for its Contra policy after CIA involvement in the mining of Nicaraguan ports became public knowledge, and a report of the

In fiscal year 1984, the U.S. Congress approved $24 million in aid to the contras. However, the Reagan administration lost a lot of support for its Contra policy after CIA involvement in the mining of Nicaraguan ports became public knowledge, and a report of the

In 1984, the Nicaraguan government filed a suit in the

In 1984, the Nicaraguan government filed a suit in the

, presentation of the Republican Policy Committee to the U.S. Senate, 31 March 1999.Terrorist Groups and Political Legitimacy

Council on Foreign Relations. UN resolution 1160 took a similar stance. At first, NATO had stressed that KLA was "the main initiator of the violence" and that it had "launched what appears to be a deliberate campaign of provocation".. The United States (and NATO) directly supported the KLA. The CIA funded, trained and supplied the KLA (as they had earlier trained and supplied the

Terrorist Groups and Political Legitimacy

16 March 2006, prepared by Michael Moran In the following years, however, an ethnic Albanian insurgency emerged in southern Serbia (1999–2001) and in Macedonia (2001). The EU condemned what it described as the "extremism" and use of "illegal terrorist actions" by the group active in southern Serbia. Since the war, many of the KLA leaders have been active in the political leadership of the

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

has at various times in recent history provided support to terrorist

Terrorism, in its broadest sense, is the use of criminal violence to provoke a state of terror or fear, mostly with the intention to achieve political or religious aims. The term is used in this regard primarily to refer to intentional violen ...

and paramilitary

A paramilitary is an organization whose structure, tactics, training, subculture, and (often) function are similar to those of a professional military, but is not part of a country's official or legitimate armed forces. Paramilitary units carr ...

organizations around the world. It has also provided assistance to numerous authoritarian regimes that have used state terrorism

State terrorism refers to acts of terrorism which a state conducts against another state or against its own citizens.Martin, 2006: p. 111.

Definition

There is neither an academic nor an international legal consensus regarding the proper def ...

as a tool of repression.

American support for non-state terrorists has been prominent in Latin America

Latin America or

* french: Amérique Latine, link=no

* ht, Amerik Latin, link=no

* pt, América Latina, link=no, name=a, sometimes referred to as LatAm is a large cultural region in the Americas where Romance languages — languages derived ...

and the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

. From 1981 to 1991, the United States provided weapons, training, and extensive financial and logistical support to the Contra

Contra may refer to:

Places

* Contra, Virginia

* Contra Costa Canal, an aqueduct in the U.S. state of California

* Contra Costa County, California

* Tenero-Contra, a municipality in the district of Locarno in the canton of Ticino in Switzerland ...

rebels in Nicaragua, who used terror tactics in their fight against the Nicaraguan government. At various points the United States also provided training, arms, and funds to terrorists among Cuban exiles

The Cuban exodus is the mass emigration of Cubans from the island of Cuba after the Cuban Revolution of 1959. Throughout the exodus millions of Cubans from diverse social positions within Cuban society became disillusioned with life in Cuba ...

, such as Orlando Bosch

Orlando Bosch Ávila (18 August 1926 – 27 April 2011) was a Cuban exile militant, who headed the Coordination of United Revolutionary Organizations (CORU), described by the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation as a terrorist or ...

and Luis Posada Carriles

Luis Clemente Posada Carriles (February 15, 1928 – May 23, 2018) was a Cuban exile militant and Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) agent. He was considered a terrorist by the United States' Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and the G ...

.

Various reasons have been given to justify this support. These include destabilizing political movements that might have aligned with the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

during the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

, including popular democratic and socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

movements. Such support has also formed a part of the war on drugs

The war on drugs is a global campaign, led by the United States federal government, of drug prohibition, military aid, and military intervention, with the aim of reducing the illegal drug trade in the United States.Cockburn and St. Clair, 1 ...

. Support was often geared toward ensuring a conducive environment for American corporate interests abroad, especially when these interests came under threat from democratic governments.

Cuban exiles

Starting in 1961 the U.S. government, through the

Starting in 1961 the U.S. government, through the military

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. It is typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with its members identifiable by their distinct ...

and the Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

, engaged in an extensive campaign of state-sponsored terrorism against civilian and military targets in Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribb ...

. The terrorist attacks killed a significant number of civilians. The U.S. armed, trained, funded and directed the terrorists, largely Cuban expatriates. Andrew Bacevich

Andrew J. Bacevich Jr. (, ; born July 5, 1947) is an American historian specializing in international relations, security studies, American foreign policy, and American diplomatic and military history. He is a Professor Emeritus of Internationa ...

, Professor of International Relations and History at Boston University, wrote of the campaign:

Among the most prominent of these terrorists were Orlando Bosch

Orlando Bosch Ávila (18 August 1926 – 27 April 2011) was a Cuban exile militant, who headed the Coordination of United Revolutionary Organizations (CORU), described by the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation as a terrorist or ...

and Luis Posada Carriles

Luis Clemente Posada Carriles (February 15, 1928 – May 23, 2018) was a Cuban exile militant and Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) agent. He was considered a terrorist by the United States' Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and the G ...

, who were implicated in the 1976 bombing of a Cuban plane. Bosch was also held to be responsible for 30 other terrorist acts, while Carriles was a former CIA agent convicted of numerous terrorist acts committed while he was linked to the agency. Other Cuban exiles involved in terrorist acts, Jose Dionisio Suarez and Virgilio Paz Romero, two other Cuban exiles who assassinated the Chilean diplomat Orlando Letelier

Marcos Orlando Letelier del Solar (13 April 1932 – 21 September 1976) was a Chilean economist, politician and diplomat during the presidency of Salvador Allende. A refugee from the Military government of Chile (1973–1990), military dictato ...

in Washington in 1976, were also released by the administration of George H.W. Bush.

Orlando Bosch

Bosch was a contemporary ofFidel Castro

Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz (; ; 13 August 1926 – 25 November 2016) was a Cuban revolutionary and politician who was the leader of Cuba from 1959 to 2008, serving as the prime minister of Cuba from 1959 to 1976 and president from 1976 to 20 ...

at the University of Havana

The University of Havana or (UH, ''Universidad de La Habana'') is a university located in the Vedado district of Havana, the capital of the Republic of Cuba. Founded on January 5, 1728, the university is the oldest in Cuba, and one of the firs ...

, where he was involved with the student cells that eventually became a part of the Cuban revolution. However, Bosch became disillusioned with Castro's regime, and participated in a failed rebellion in 1960. He became the leader of the Insurrectional Movement of Revolutionary Recovery (MIRR), and also joined efforts to assassinate Castro along with Luis Posada Carriles

Luis Clemente Posada Carriles (February 15, 1928 – May 23, 2018) was a Cuban exile militant and Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) agent. He was considered a terrorist by the United States' Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and the G ...

. The CIA later confirmed that they had received support from Bosch in 1962, but ceased contact with him after he requested financial support to mount airstrikes against Cuba in 1963.

Kornbluh, Peter (9 June 2005"The Posada File: Part II."

National Security Archive. He was the head of

Coordination of United Revolutionary Organizations

The Coordination of United Revolutionary Organizations ( es, Coordinación de Organizaciones Revolucionarias Unidas, CORU) was a militant group responsible for a number of terrorist activities directed at the Cuban government of Fidel Castro. It ...

, which the FBI has described as "an anti- Castro terrorist

Terrorism, in its broadest sense, is the use of criminal violence to provoke a state of terror or fear, mostly with the intention to achieve political or religious aims. The term is used in this regard primarily to refer to intentional violen ...

umbrella organization". Former U.S. Attorney General Dick Thornburgh

Richard Lewis Thornburgh (July 16, 1932 – December 31, 2020) was an American lawyer, author, and Republican politician who served as the 41st governor of Pennsylvania from 1979 to 1987, and then as the United States attorney general fr ...

called Bosch an "unrepentant terrorist".

In 1968, he was convicted of firing a bazooka

Bazooka () is the common name for a man-portable recoilless anti-tank rocket launcher weapon, widely deployed by the United States Army, especially during World War II. Also referred to as the "stovepipe", the innovative bazooka was among the ...

at a Polish cargo ship bound for Havana that had been docked in Miami. He was sentenced to 10 years in prison and released on parole

Parole (also known as provisional release or supervised release) is a form of early release of a prison inmate where the prisoner agrees to abide by certain behavioral conditions, including checking-in with their designated parole officers, or ...

in 1974. He immediately broke parole and traveled around Latin America. He was eventually arrested in Venezuela for planning to bomb the Cuban embassy there. The Venezuelan government offered to extradite him to the United States, but the offer was declined. He was released quickly and moved to Chile, and according to the US government, spent two years attempting postal bombings of Cuban embassies in four countries.

Bosch eventually ended up in the Dominican Republic

The Dominican Republic ( ; es, República Dominicana, ) is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean region. It occupies the eastern five-eighths of the island, which it shares with ...

, where he joined the effort to consolidate Cuban exile militants into the Coordination of United Revolutionary Organizations

The Coordination of United Revolutionary Organizations ( es, Coordinación de Organizaciones Revolucionarias Unidas, CORU) was a militant group responsible for a number of terrorist activities directed at the Cuban government of Fidel Castro. It ...

(CORU). The CORU's operations included the failed assassination of the Cuban ambassador to Argentina, and the bombing of the Mexican Embassy in Guatemala City. Along with Posada, he worked with the DINA

Dina ( ar, دينا, he, דִּינָה, also spelled Dinah, Dena, Deena) is a female given name.

Women

* Dina bint Abdul-Hamid (1929–2019), Queen consort of Jordan, first wife of King Hussein

* Princess Dina Mired of Jordan (born 1965), Princ ...

agent Michael Townley

Michael Vernon Townley (born December 5, 1942, in Waterloo, Iowa) is an American-born former agent of the Dirección de Inteligencia Nacional (DINA), the secret police of Chile during the regime of Augusto Pinochet. In 1978, Townley pled guilty t ...

to plan the assassination of Letelier, which was carried out in September 1976. Two other Cuban exiles involved in the assassination, Jose Dionisio Suarez and Virgilio Paz Romero, were later released by the administration of George H.W. Bush. Bosch was also implicated in the 1976 bombing of a Cuban plane flying to Havana from Venezuela in which all 73 civilians on board were killed, although Posada and he were acquitted after a lengthy trial. Documents released subsequently showed that the CIA had a source with advance knowledge of the bombing. The U.S. Justice Department recorded that Bosch was also responsible for 30 other attacks. He returned to Miami, where he was arrested for violating parole. The Justice department recommended that he be deported. However, Bush overturned this recommendation, and had him released from custody with the stipulation that he "renounce" violence.

Luis Posada Carriles

Luis Posada Carriles, a former CIA agent who has been designated by scholars and journalists as a terrorist, also came into contact with Castro during his student days, but fled Cuba after the 1959 revolution, and helped organize the failed

Luis Posada Carriles, a former CIA agent who has been designated by scholars and journalists as a terrorist, also came into contact with Castro during his student days, but fled Cuba after the 1959 revolution, and helped organize the failed Bay of Pigs invasion

The Bay of Pigs Invasion (, sometimes called ''Invasión de Playa Girón'' or ''Batalla de Playa Girón'' after the Playa Girón) was a failed military landing operation on the southwestern coast of Cuba in 1961 by Cuban exiles, covertly fin ...

. Following the invasion, Carriles was trained for a time at the Fort Benning

Fort Benning is a United States Army post near Columbus, Georgia, adjacent to the Alabama– Georgia border. Fort Benning supports more than 120,000 active-duty military, family members, reserve component soldiers, retirees and civilian employee ...

station of the U.S. Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cl ...

. He then relocated to Venezuela, where he came into contact with Orlando Bosch.Bardach, Ann Louise. Cuba Confidential: Love and Vengeance in Miami and Havana. p180-223. Along with Orlando Bosch and others, he founded the Coordination of United Revolutionary Organizations, which has been described as an umbrella of anti-Castro terrorist groups.

In 1976, Cubana Flight 455

Cubana may refer to:

* a woman born in Cuba

* Cubana de Aviación, an airline of Cuba

* Cubana, West Virginia

Cubana is an unincorporated community in Randolph County, West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian, Mid-Atl ...

was blown up in mid-air, killing all 73 people on board. Carriles was arrested for masterminding the operation, and later acquitted. He and several CIA-linked anti-Castro

The Cuban dissident movement is a political movement in Cuba whose aim is to replace the current government with a liberal democracy. According to Human Rights Watch, the Cuban government represses nearly all forms of political dissent.

Backgro ...

Cuban exile

A Cuban exile is a person who emigrated from Cuba in the Cuban exodus. Exiles have various differing experiences as emigrants depending on when they migrated during the exodus.

Demographics Social class

Cuban exiles would come from various ec ...

s and members of the Venezuela

Venezuela (; ), officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela ( es, link=no, República Bolivariana de Venezuela), is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many islands and islets in th ...

n intelligence agency DISIP

DISIP (General Sectoral Directorate of Intelligence and Prevention Services) was an intelligence and counter-intelligence agency inside and outside of Venezuela between 1969 and 2009 when SEBIN was created by former President Hugo Chavez. DISIP was ...

were implicated by the evidence. Political complications quickly arose when Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribb ...

accused the US government

The federal government of the United States (U.S. federal government or U.S. government) is the national government of the United States, a federal republic located primarily in North America, composed of 50 states, a city within a feder ...

of being an accomplice to the attack. CIA documents released in 2005 indicate that the agency "had concrete advance intelligence, as early as June 1976, on plans by Cuban exile terrorist groups to bomb a Cubana airliner." Carriles denies involvement but provides many details of the incident in his book ''Los caminos del guerrero'' (The Warrior's Paths).

After a series of arrests and escapes, Carriles returned to the CIA fold in 1985 by joining their support operations to the Contra

Contra may refer to:

Places

* Contra, Virginia

* Contra Costa Canal, an aqueduct in the U.S. state of California

* Contra Costa County, California

* Tenero-Contra, a municipality in the district of Locarno in the canton of Ticino in Switzerland ...

terrorists in Nicaragua, which were being run by Oliver North. His job included air dropping military supplies, for which he was paid a significant salary. He later admitted to playing a part in the Iran-Contra affair. In 1997, a series of terrorist bombings occurred in Cuba, and Carriles was implicated. The bombings were said to be targeted at the growing tourism there. Carriles admitted that the lone conviction in the case had been of a mercenary under his command, and also made a confession (later retracted) that he had planned the incident. Human Rights Watch

Human Rights Watch (HRW) is an international non-governmental organization, headquartered in New York City, that conducts research and advocacy on human rights. The group pressures governments, policy makers, companies, and individual human ...

stated that although Carriles might no longer receive active assistance, he benefited from the tolerant attitude of the U.S. government. In 2000, Carriles was arrested and convicted in Panama of attempting to assassinate Fidel Castro.

In 2005, Posada was held by U.S. authorities in Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

on a charge of illegal presence on national territory, but the charges were dismissed on May 8, 2007. On September 28, 2005 a U.S. immigration judge ruled that Posada could not be deported, finding that he faced the threat of torture in Venezuela. Likewise, the US government has refused to send Posada to Cuba, saying he might face torture. His release on bail on April 19, 2007 elicited angry reactions from the Cuban and Venezuelan governments. The U.S. Justice Department

The United States Department of Justice (DOJ), also known as the Justice Department, is a federal executive department of the United States government tasked with the enforcement of federal law and administration of justice in the United States ...

had urged the court to keep him in jail because he was "an admitted mastermind of terrorist plots and attacks", a flight

Flight or flying is the process by which an object moves through a space without contacting any planetary surface, either within an atmosphere (i.e. air flight or aviation) or through the vacuum of outer space (i.e. spaceflight). This can be a ...

risk and a danger to the community. On September 9, 2008 the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

The United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit (in case citations, 5th Cir.) is a federal court with appellate jurisdiction over the district courts in the following federal judicial districts:

* Eastern District of Louisiana

* ...

reversed the District Court's order dismissing the indictment and remanded the case to the District Court. On April 8, 2009 the United States Attorney

United States attorneys are officials of the U.S. Department of Justice who serve as the chief federal law enforcement officers in each of the 94 U.S. federal judicial districts. Each U.S. attorney serves as the United States' chief federal ...

filed a superseding indictment in the case. Carriles' trial ended on April 8, 2011 with a jury acquitting him on all charges. Peter Kornbluh described him as "one of the most dangerous terrorists in recent history" and the "godfather of Cuban exile violence."

Colombian paramilitary groups

The first Colombian paramilitary groups were organized by the Colombian government following recommendations made by U.S. military counterinsurgency advisers who were sent to Colombia in the early 1960s during the

The first Colombian paramilitary groups were organized by the Colombian government following recommendations made by U.S. military counterinsurgency advisers who were sent to Colombia in the early 1960s during the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

to combat leftist politicians, activists and guerrillas.

Paramilitary groups were responsible for most of the human rights violations in the latter half of the ongoing Colombian conflict

The Colombian conflict ( es, link=no, Conflicto armado interno de Colombia) began on May 27, 1964, and is a low-intensity asymmetric war between the government of Colombia, far-right paramilitary groups, crime syndicates, and far-left guerr ...

. According to several international human rights and governmental organizations, right-wing paramilitary groups were responsible for at least 70 to 80% of political murders in Colombia in a given year during the 80s and 90s.HRW, 1996"III: The Intelligence Reorganization"

Paramilitary violence and terrorism there was principally targeted to peasants, unionists, indigenous people, human rights workers, teachers and left-wing political activists or their supporters.

Plan Lazo

In October 1959, the United States sent a "Special Survey Team", composed ofcounterinsurgency

Counterinsurgency (COIN) is "the totality of actions aimed at defeating irregular forces". The Oxford English Dictionary defines counterinsurgency as any "military or political action taken against the activities of guerrillas or revolutionari ...

experts, to investigate Colombia's internal security situation, due to the increased prevalence of armed communist groups in rural Colombia which formed during and after ''La Violencia

''La Violencia'' (, The Violence) was a ten-year civil war in Colombia from 1948 to 1958, between the Colombian Conservative Party and the Colombian Liberal Party, fought mainly in the countryside.

''La Violencia'' is considered to have begu ...

''. Three years later, in February 1962, a Fort Bragg

Fort Bragg is a military installation of the United States Army in North Carolina, and is one of the largest military installations in the world by population, with around 54,000 military personnel. The military reservation is located within Cu ...

top-level U.S. Special Warfare team headed by Special Warfare Center commander General William P. Yarborough

Lieutenant General William Pelham Yarborough (May 12, 1912 – December 6, 2005) was a senior United States Army officer. Yarborough designed the U.S. Army's parachutist badge, paratrooper or 'jump' boots, and the airborne jump uniform. He is ...

, visited Colombia for a second survey.Livingstone, 2004: p. 155

In a secret supplement to his report to the Joint Chiefs of Staff

The Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) is the body of the most senior uniformed leaders within the United States Department of Defense, that advises the president of the United States, the secretary of defense, the Homeland Security Council and the ...

, Yarborough encouraged the creation and deployment of a paramilitary force to commit sabotage

Sabotage is a deliberate action aimed at weakening a polity, effort, or organization through subversion, obstruction, disruption, or destruction. One who engages in sabotage is a ''saboteur''. Saboteurs typically try to conceal their identitie ...

and terrorist acts against communists, stating:

The new counter-insurgency policy was instituted as Plan Lazo

"Marquetalia Republic" was an unofficial term used to refer to one of the enclaves in rural Colombia which communist peasant guerrillas held during the aftermath of "La Violencia" (approximately 1948 to 1958). Congressmen of the Colombian Conse ...

in 1962 and called for both military operations and civic action program

A civic action program also known as civic action project is a type of operation designed to assist an area by using the capabilities and resources of a military force or civilian organization to conduct long-term programs or short-term projects. ...

s in violent areas. Following Yarborough's recommendations, the Colombian military recruited civilians into paramilitary "civil defense" groups which worked alongside the military in its counter-insurgency campaign, as well as in civilian intelligence networks to gather information on guerrilla activity. Among other policy recommendations, the US team advised that "in order to shield the interests of both Colombian and US authorities against 'interventionist' charges, any special aid given for internal security was to be sterile and covert in nature."Stokes, 2005: pp. 71-72 It was not until the early part of the 1980s that the Colombian government attempted to move away from the counterinsurgency strategy represented by Plan Lazo and Yarborough's 1962 recommendations.Stokes, 2005: p. 74

Armed Forces Directive No. 200-05/91

In 1990, the United States formed a team that included representatives of the U.S. Embassy's Military Group,U.S. Southern Command

The United States Southern Command (USSOUTHCOM), located in Doral, Florida in Greater Miami, is one of the eleven unified combatant commands in the United States Department of Defense. It is responsible for providing contingency planning, o ...

, the DIA, and the CIA

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

in order to give advice on the reshaping of several of the Colombian military's local intelligence networks, ostensibly to aid the Colombian military in "counter-narcotics" efforts. Advice was also solicited from the British and Israeli military intelligence, but the U.S. proposals were ultimately selected by the Colombian military. The result of these meetings was ''Armed Forces Directive 200-05/91'', issued by the Colombian Defense Ministry

The Ministry of National Defence ( es, Ministerio de Defensa Nacional) is the national executive ministry of the Government of Colombia charged with coordinating and supervising all agencies and functions of the government relating directly to n ...

in May 1991. However, the order itself made no mention of drugs or counter-narcotics operations at all, and instead focused exclusively on creating covert intelligence networks to combat the insurgency.HRW, 1996"Appendix A: Colombian Armed Forces Directive No. 200-05/91"

Human Rights Watch

Human Rights Watch (HRW) is an international non-governmental organization, headquartered in New York City, that conducts research and advocacy on human rights. The group pressures governments, policy makers, companies, and individual human ...

concluded that these intelligence networks subsequently laid the groundwork for an illegal, covert partnership between the military and paramilitaries. Human Rights Watch argued that the restructuring process solidified links between members of the Colombian military and civilian members of paramilitary groups, by incorporating them into several of the local intelligence networks and by cooperating with their activities. In effect, HRW believed that this further consolidated a "secret network that relied on paramilitaries not only for intelligence, but to carry out murder". Human Rights Watch argued that this situation allowed the Colombian government and military to plausibly deny links to or responsibility for paramilitary human rights abuses. Human Rights Watch stated that the military intelligence networks created by the U.S. reorganization appeared to have dramatically increased violence, stating that the "recommendations were given despite the fact that some of the U.S. officials who collaborated with the team knew of the Colombian military's record of human rights abuses and its ongoing relations with paramilitaries".

Human Rights Watch stated that while "not all paramilitaries are intimate partners with the military", the existing partnership between paramilitaries and the Colombian military was "a sophisticated mechanism, in part supported by years of advice, training, weaponry, and official silence by the United States, that allows the Colombian military to fight a dirty war

The Dirty War ( es, Guerra sucia) is the name used by the military junta or civic-military dictatorship of Argentina ( es, dictadura cívico-militar de Argentina, links=no) for the period of state terrorism in Argentina from 1974 to 1983 a ...

and Colombian officialdom to deny it."HRW, 1996"Conclusions and Recommendations"

As an example of increased violence and "dirty war" tactics, Human Rights Watch cited a partnership between the Colombian Navy and the MAS, in

Barrancabermeja

Barrancabermeja is a city in Colombia, located on the shore of the Magdalena River, in the western part of the department of Santander. It is home to the largest oil refinery in the country, under direct management of ECOPETROL. Barrancabermeja ...

where: "In partnership with MAS, the navy intelligence network set up in Barrancabermeja adopted as its goal not only the elimination of anyone perceived as supporting the guerrillas, but also members of the political opposition, journalists, trade unionists, and human rights workers, particularly if they investigated or criticized their terror tactics."

Los Pepes

In 1992,Pablo Escobar

Pablo Emilio Escobar Gaviria (; ; 1 December 19492 December 1993) was a Colombian drug lord and narcoterrorist who was the founder and sole leader of the Medellín Cartel. Dubbed "the king of cocaine", Escobar is the wealthiest criminal i ...

escaped from his luxury prison, La Catedral

La Catedral was a personal prison overlooking the city of Medellín, in Colombia. The prison was built to specifications ordered by Medellín Cartel leader Pablo Escobar, under a 1991 agreement with the Colombian government in which Escobar w ...

. Shortly thereafter, the Calí drug cartel, dissidents within the Medellín cartel and the MAS worked together to create a new paramilitary organization known as ''Perseguidos por Pablo Escobar'' ("People Persecuted by Pablo Escobar", Los Pepes) with the purpose of tracking down and killing Pablo Escobar and his associates. The leader of the organization was Fidel Castaño.Livingstone, 2004p. 159

/ref>

, ''National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 243'',

National Security Archive

The National Security Archive is a 501(c)(3) non-governmental, non-profit research and archival institution located on the campus of the George Washington University in Washington, D.C. Founded in 1985 to check rising government secrecy. The N ...

, February 17, 2008

Scott, 2003p. 88

/ref> The Calí cartel provided $50 million for weapons, informants, and assassins, with in hope of wiping out their primary rivals in the cocaine business.Kirk, 2003: pp. 156–158 Both Colombian and U.S. government agencies (including the DEA, CIA and State Department) provided intelligence to Los Pepes. The

Institute for Policy Studies

The Institute for Policy Studies (IPS) is an American progressive think tank started in 1963 that is based in Washington, D.C. It was directed by John Cavanagh from 1998 to 2021. In 2021 Tope Folarin was announced as new Executive Director. ...

is searching for details of connections the CIA and DEA had to Los Pepes. They have launched a lawsuit under the Freedom of Information Act Freedom of Information Act may refer to the following legislations in different jurisdictions which mandate the national government to disclose certain data to the general public upon request:

* Freedom of Information Act 1982, the Australian act

* ...

against the CIA. That suit has resulted in the declassification of thousands of documents from the CIA as well as other U.S. agencies, including the Department of State, Drug Enforcement Administration, Defense Intelligence Agency and the U.S Coast Guard. These documents have been made public at the websitePepes Project

Years of Lead

The Years of Lead was a period of socio-political turmoil inItaly

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

that lasted from the late 1960s into the early 1980s. This period was marked by a wave of terrorism

Terrorism, in its broadest sense, is the use of criminal violence to provoke a state of terror or fear, mostly with the intention to achieve political or religious aims. The term is used in this regard primarily to refer to intentional violen ...

carried out by both right-wing and left-wing paramilitary groups. It was concluded that the former were supported by the United States as a strategy of tension

A strategy of tension ( it, strategia della tensione) is a policy wherein violent struggle is encouraged rather than suppressed. The purpose is to create a general feeling of insecurity in the population and make people seek security in a strong go ...

. (With links to juridical sentences and Parliamentary Report by the Italian Commission on Terrorism)

General , commander of the counter-intelligence section of the Italian military intelligence service from 1971 to 1975, stated that his men in the region of Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

discovered a right-wing terrorist cell that had been supplied with military explosives from Germany, and alleged that US intelligence services instigated and abetted right-wing terrorism

Right-wing terrorism, hard right terrorism, extreme right terrorism or far-right terrorism is terrorism that is motivated by a variety of different right-wing and far-right ideologies, most prominently, it is motivated by neo-Nazism, anti-com ...

in Italy during the 1970s.

According to the investigation of Italian judge Guido Salvini, the neo-fascist

Neo-fascism is a post-World War II far-right ideology that includes significant elements of fascism. Neo-fascism usually includes ultranationalism, racial supremacy, populism, authoritarianism, nativism, xenophobia, and anti-immigration ...

organizations involved in the strategy of tension, "''La Fenice'', ''Avanguardia nazionale

The National Vanguard ( it, Avanguardia Nazionale) is a name that has been used for at least two neo-fascist and neo-Nazi groups in Italy.

Original group

The original National Vanguard was an extra-parliamentary movement formed as a breakaway gr ...

'', '' Ordine nuovo''" were the "troops" of "clandestine armed forces", directed by components of the "state apparatus related to the CIA."

Any relationship of the CIA to the terrorist attacks perpetrated in Italy during the Years of Lead is the subject of debate. Switzerland and Belgium have had parliamentary inquiries into the matter.

Piazza Fontana bombing

The Piazza Fontana Bombing was a terrorist attack that occurred on December 12, 1969 at 16:37, when a bomb exploded at the headquarters of

The Piazza Fontana Bombing was a terrorist attack that occurred on December 12, 1969 at 16:37, when a bomb exploded at the headquarters of Banca Nazionale dell'Agricoltura

The Banca Nazionale dell'Agricoltura or BNA, was an Italian bank that existed from 1921 to 2000.

History

Banca Nazionale dell'Agricoltura was established in Milan in 1921 by Count (who after his death was succeeded by his nephew Giovanni Aulet ...

(National Agrarian Bank) in Piazza Fontana in Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city ...

, killing 17 people and wounding 88. The same afternoon, three more bombs were detonated in Rome and Milan, and another was found undetonated.

In 1998, Milan judge Guido Salvini indicted U.S. Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage o ...

officer David Carrett

The Piazza Fontana bombing ( it, Strage di Piazza Fontana) was a terrorist attack that occurred on 12 December 1969 when a bomb exploded at the headquarters of Banca Nazionale dell'Agricoltura (the National Agricultural Bank) in Piazza Fon ...

on charges of political and military espionage

Espionage, spying, or intelligence gathering is the act of obtaining secret or confidential information ( intelligence) from non-disclosed sources or divulging of the same without the permission of the holder of the information for a tang ...

for his alleged participation in the Piazza Fontana bombing et al. Salvini also opened up a case against Sergio Minetto, an Italian official of the U.S.-NATO intelligence network, and "collaboratore di giustizia" Carlo Digilio (Uncle Otto), who served as the CIA

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

coordinator in Northeastern Italy

Northeast Italy ( it, Italia nord-orientale or just ) is one of the five official statistical regions of Italy used by the Istituto Nazionale di Statistica, National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT), a Italian NUTS level 1 regions, first level ...

in the sixties and seventies. The newspaper ''la Repubblica

''la Repubblica'' (; the Republic) is an Italian daily general-interest newspaper. It was founded in 1976 in Rome by Gruppo Editoriale L'Espresso (now known as GEDI Gruppo Editoriale) and led by Eugenio Scalfari, Carlo Caracciolo and Arno ...

'' reported that Carlo Rocchi, CIA's man in Milan, was discovered in 1995 searching for information concerning Operation Gladio

Operation Gladio is the codename for clandestine " stay-behind" operations of armed resistance that were organized by the Western Union (WU), and subsequently by NATO and the CIA, in collaboration with several European intelligence agencies durin ...

.

A 2000 parliamentary report published by the center-left Olive Tree coalition

The Olive Tree ( it, L'Ulivo) was a denomination used for several successive centre-left political and electoral alliances of Italian political parties from 1995 to 2007.

The historical leader and ideologue of these coalitions was Romano Prodi ...

claimed that "U.S. intelligence agents were informed in advance about several right-wing terrorist bombings, including the December 1969 Piazza Fontana bombing in Milan and the Piazza della Loggia bombing

The Piazza della Loggia bombing was a bombing that took place on the morning of 28 May 1974, in Brescia, Italy during an anti-fascist protest. The terrorist attack killed eight people and wounded 102. The bomb was placed inside a rubbish bin at t ...

in Brescia five years later, but did nothing to alert the Italian authorities or to prevent the attacks from taking place." It also alleged that Pino Rauti (current leader of the MSI Fiamma-Tricolore party), a journalist and founder of the far-right Ordine Nuovo (New Order) subversive organization, received regular funding from a press officer at the U.S. embassy in Rome. "So even before the 'stabilising' plans that Atlantic circles had prepared for Italy became operational through the bombings, one of the leading members of the subversive right was literally in the pay of the American embassy in Rome", the report says.

Paolo Emilio Taviani

Paolo Emilio Taviani (6 November 1912 – 18 June 2001) was an Italian political leader, economist, and historian of the career of Christopher Columbus. He was a partisan leader in Liguria, a Gold Medal of the Resistance, then a member of the ...

, the Christian Democrat

Christian democracy (sometimes named Centrist democracy) is a political ideology that emerged in 19th-century Europe under the influence of Catholic social teaching and neo-Calvinism.

It was conceived as a combination of modern democratic ...

co-founder of Gladio

Operation Gladio is the codename for clandestine "stay-behind" operations of armed resistance that were organized by the Western Union (WU), and subsequently by NATO and the CIA, in collaboration with several European intelligence agencies during ...

(NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two N ...

's stay-behind

In a stay-behind operation, a country places secret operatives or organizations in its own territory, for use in case an enemy occupies that territory. If this occurs, the operatives would then form the basis of a resistance movement or act as sp ...

anti-Communist

Anti-communism is political and ideological opposition to communism. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in the Russian Empire, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, when the United States and the ...

organization in Italy), told investigators that the SID military intelligence service was about to send a senior officer from Rome to Milan to prevent the bombing, but decided to send a different officer from Padua in order to put the blame on left-wing anarchists. Taviani also alleged in an August 2000 interview to ''Il Secolo XIX

''Il Secolo XIX'' ( ) is an Italian newspaper published in Genoa, Italy, founded in March 1886, subsequently acquired by Ferdinando Maria Perrone in 1897 from Ansaldo. It is one of the first Italian newspapers to be printed in colour.

On 16 J ...

'' newspaper: "It seems to me certain, however, that agents of the CIA were among those who supplied the materials and who muddied the waters of the investigation."Paolo Emilio Tavianiobituary by Philip Willan, in ''

The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers '' The Observer'' and '' The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the ...

'', June 21, 2001

Guido Salvini said "The role of the Americans was ambiguous, halfway between knowing and not preventing and actually inducing people to commit atrocities."

According to Vincenzo Vinciguerra Vincenzo Vinciguerra (born 3 January 1949) is an Italian neo-fascist activist, a former member of the ''Avanguardia Nazionale'' ("National Vanguard") and '' Ordine Nuovo'' ("New Order"). He is currently serving a life-sentence for the murder of thr ...

, the terrorist attack was supposed to push then Interior Minister Mariano Rumor

Mariano Rumor (; 16 June 1915 – 22 January 1990) was an Italian politician and statesman. A member of the Christian Democracy (DC), he served as the 39th Prime Minister of Italy from December 1968 to August 1970 and again from July 1973 to No ...

to declare a state of emergency

A state of emergency is a situation in which a government is empowered to be able to put through policies that it would normally not be permitted to do, for the safety and protection of its citizens. A government can declare such a state du ...

.

Nicaraguan Contras

From 1979 to 1990, the United States provided financial, logistical and military support to the Contra rebels in Nicaragua, who used terrorist tactics in their war against the Nicaraguan governmentGrandin, p. 89 and carried out more than 1300 terrorist attacks. This support persisted despite widespread knowledge of the human rights violations committed by the Contras.Background

In 1979, the

In 1979, the Sandinista National Liberation Front

The Sandinista National Liberation Front ( es, Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional, FSLN) is a socialist political party in Nicaragua. Its members are called Sandinistas () in both English and Spanish. The party is named after Augusto ...

(FSLN) overthrew the dictatorial regime of Anastasio Somoza Debayle

Anastasio "Tachito" Somoza Debayle (; 5 December 1925 – 17 September 1980) was the President of Nicaragua from 1 May 1967 to 1 May 1972 and from 1 December 1974 to 17 July 1979. As head of the National Guard, he was ''de facto'' ruler of t ...

, and established a revolutionary government in Nicaragua. The Somoza dynasty had been receiving military and financial assistance from the United States since 1936. Following their seizure of power, the Sandinistas ruled the country first as part of a Junta of National Reconstruction

The Junta of National Reconstruction (''Junta de Gobierno de Reconstrucción Nacional'') was the provisional government of Nicaragua from the fall of the Somoza dictatorship in July 1979 until January 1985, with the election of Sandinista Nat ...

, and later as a democratic government following free and fair elections in 1984.

The Sandinistas did not attempt to create a communist society

In Marxist thought, a communist society or the communist system is the type of society and economic system postulated to emerge from technological advances in the productive forces, representing the ultimate goal of the political ideology of co ...

or communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, ...

economic system; instead, their policy advocated a social democracy and a mixed economy

A mixed economy is variously defined as an economic system blending elements of a market economy with elements of a planned economy, markets with state interventionism, or private enterprise with public enterprise. Common to all mixed economie ...

.LaFeber, p. 350LaFeber, p. 238Latin American Studies Association, p. 5Grandin, p. 112 The government sought the aid of Western Europe, who were opposed to the U.S. embargo against Nicaragua, to escape dependency on the Soviet Union. However, the U.S. administration viewed the leftist Sandinista government as undemocratic and totalitarian under the ties of the Soviet-Cuban model and tried to paint the Contras as freedom fighter

A resistance movement is an organized effort by some portion of the civil population of a country to withstand the legally established government or an occupying power and to disrupt civil order and stability. It may seek to achieve its objectives ...

s.

The Sandinista government headed by Daniel Ortega

José Daniel Ortega Saavedra (; born 11 November 1945) is a Nicaraguan revolutionary and politician serving as President of Nicaragua since 2007. Previously he was leader of Nicaragua from 1979 to 1990, first as coordinator of the Junta of Na ...

won decisively in the 1984 Nicaraguan elections. The U.S. government explicitly planned to back the Contras, various rebel groups collectively that were formed in response to the rise of the Sandinistas, as a means to damage the Nicaraguan economy and force the Sandinista government to divert its scarce resources toward the army and away from social and economic programs.Grandin, p. 116

Covert operations

The United States began to support Contra activities against the Sandinista government by December 1981, with the CIA at the forefront of operations.Hamilton & Inouye, "Report of the Congressional Committees Investigating the Iran-Contra Affair", p. 3 The CIA provided the Contras with planning and operational direction and assistance, weapons, food, and training, in what was described as the "most ambitious" covert operation in more than a decade.Hamilton & Inouye, "Report of the Congressional Committees Investigating the Iran-Contra Affair", p. 33 One of the purposes the CIA hoped to achieve by these operations was an aggressive and violent response from the Sandinista government which in turn could be used as a pretext for further military actions. The Contra campaign against the government included frequent and widespread acts of terror. The economic and social reforms enacted by the government enjoyed some popularity; as a result, the Contras attempted to disrupt these programs. This campaign included the destruction of health centers and hospitals that the Sandinista government had established, in order to disrupt their control over the populace. Schools were also destroyed, as the literacy campaign conducted by the government was an important part of its policy. The Contras also committed widespread kidnappings, murder, and rape. The kidnappings and murder were a product of the "low-intensity warfare" that the Reagan Doctrine prescribed as a way to disrupt social structures and gain control over the population. Also known as "unconventional warfare", advocated for and defined by the World Anti-Communist League's (WACL) retired U.S. Army Major General John Singlaub as, "low intensity actions, such as sabotage, terrorism, assassination and guerrilla warfare". In some cases, more indiscriminate killing and destruction also took place. The Contras also carried out a campaign of economic sabotage, and disrupted shipping by planting underwater mines in Nicaragua's Port of Corinto. The Reagan administration supported this by imposing a full trade embargo. In fiscal year 1984, the U.S. Congress approved $24 million in aid to the contras. However, the Reagan administration lost a lot of support for its Contra policy after CIA involvement in the mining of Nicaraguan ports became public knowledge, and a report of the

In fiscal year 1984, the U.S. Congress approved $24 million in aid to the contras. However, the Reagan administration lost a lot of support for its Contra policy after CIA involvement in the mining of Nicaraguan ports became public knowledge, and a report of the Bureau of Intelligence and Research

The Bureau of Intelligence and Research (INR) is an intelligence agency in the United States Department of State. Its central mission is to provide all-source intelligence and analysis in support of U.S. diplomacy and foreign policy. INR i ...

commissioned by the State Department

The United States Department of State (DOS), or State Department, is an executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the country's foreign policy and relations. Equivalent to the ministry of foreign affairs of other na ...

found that Reagan had exaggerated claims about Soviet interference in Nicaragua. Congress cut off all funds for the contras in 1985 with the third Boland Amendment.

As a result, the Reagan administration sought to provide funds from other sources. Between 1984 and 1986, $34 million was routed through third countries and $2.7 million through private sources.Hamilton & Inouye, "Report of the Congressional Committees Investigating the Iran-Contra Affair", p. 4 These funds were run through the National Security Council

A national security council (NSC) is usually an executive branch governmental body responsible for coordinating policy on national security issues and advising chief executives on matters related to national security. An NSC is often headed by a n ...

, by Lt. Col. Oliver North

Oliver Laurence North (born October 7, 1943) is an American political commentator, television host, military historian, author, and retired United States Marine Corps lieutenant colonel.

A veteran of the Vietnam War, North was a National Secu ...

, who created an organization called "The Enterprise" which served as the secret arm of the NSC staff and had its own airplanes, pilots, airfield, ship, and operatives. It also received assistance from other government agencies, especially from CIA personnel in Central America. These efforts culminated in the Iran-Contra Affair of 1986–1987, which facilitated funding for the Contras using the proceeds of arms sales to Iran. Money was also raised for the Contras through drug trafficking, which the United States was aware of. U.S. Senator John Kerry

John Forbes Kerry (born December 11, 1943) is an American attorney, politician and diplomat who currently serves as the first United States special presidential envoy for climate. A member of the Forbes family and the Democratic Party, he ...

's 1988 Committee on Foreign Relations

The United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations is a standing committee of the U.S. Senate charged with leading foreign-policy legislation and debate in the Senate. It is generally responsible for overseeing and funding foreign aid p ...

report on Contra drug links concluded that "senior U.S. policy makers were not immune to the idea that drug money was a perfect solution to the Contras' funding problems".

Propaganda

Throughout the Nicaraguan Civil War, the Reagan government conducted a campaign to shift public opinion to favor support for the Contras, and to change the vote in Congress to favor of that support.Hamilton & Inouye, p. 5 For this purpose, the National Security Council authorized the production and distribution of publications that looked favorably at the Contras, also known as "white propaganda

White propaganda is propaganda that does not hide its origin or nature. It is the most common type of propaganda and is distinguished from black propaganda which disguises its origin to discredit an opposing cause.

It typically uses standard pub ...

," written by paid consultants who did not disclose their connection to the administration. It also arranged for speeches and press conferences conveying the same message. The U.S. government continually discussed the Contras in highly favorable terms; Reagan called them the "moral equivalent of the founding fathers."

Another common theme the administration played on was the idea of returning Nicaragua to democracy, which analysts characterized as "curious," because Nicaragua had been a U.S.-supported dictatorship prior to the Sandinista revolution, and had never had a democratic government before the Sandinistas.Carothers, p. 97 There were also continued efforts to label the Sandinistas as undemocratic, although the 1984 Nicaraguan elections were generally declared fair by historians.LaFeber, p. 310

Commentators stated that this was all a part of an attempt to return Nicaragua to the state of its Central American neighbors; that is, where traditional social structures remained and American imperialist ideas were not threatened.Grandin, p. 88LaFeber, p. 15-19Carothers, p. 249 The investigation into the Iran-Contra affair led to the operation being called a massive exercise in psychological warfare.

The CIA wrote a manual for the Contras, entitled Psychological Operations in Guerrilla Warfare ('), which focused mainly on how "Armed Propaganda Teams" could build political support in Nicaragua for the Contra cause through deceit

Deception or falsehood is an act or statement that misleads, hides the truth, or promotes a belief, concept, or idea that is not true. It is often done for personal gain or advantage. Deception can involve dissimulation, propaganda and sleight o ...

, intimidation

Intimidation is to "make timid or make fearful"; or to induce fear. This includes intentional behaviors of forcing another person to experience general discomfort such as humiliation, embarrassment, inferiority, limited freedom, etc and the victi ...

, and violence

Violence is the use of physical force so as to injure, abuse, damage, or destroy. Other definitions are also used, such as the World Health Organization's definition of violence as "the intentional use of physical force or power, threatened ...

. The manual discussed assassination

Assassination is the murder of a prominent or important person, such as a head of state, head of government, politician, world leader, member of a royal family or CEO. The murder of a celebrity, activist, or artist, though they may not have ...

s. Footnote 105. The CIA claimed that the purpose of the manual was to "moderate" the extreme violence already being used by the Contras.

Leslie Cockburn

Leslie Cockburn ( ; born Leslie Corkill Redlich on September 2, 1952) is an American investigative journalist, and filmmaker. Her investigative television segments have aired on CBS, NBC, ''PBS Frontline'', and ''60 Minutes''. She has won an Emmy ...

writes that the CIA, and therefore indirectly the U.S. government and President Reagan, encouraged Contra terrorism by issuing the manual to the contras, violating Reagan's own Presidential Directive. Cockburn wrote that " e manual, ''Psychological Operations in Guerrilla Warfare'', clearly advocated a strategy of terror as the means to victory over the hearts and minds of Nicaraguans. Chapter headings such as 'Selective Use of Violence for propagandistic Effects' and 'Implicit and Explicit Terror' made that fact clear enough. ... The little booklet thus violated President Reagan's own Presidential Directive 12333, signed in December 1981, which prohibited any U.S. government employee—including the CIA—from having anything to do with assassinations."

International Court of Justice ruling

In 1984, the Nicaraguan government filed a suit in the

In 1984, the Nicaraguan government filed a suit in the International Court of Justice

The International Court of Justice (ICJ; french: Cour internationale de justice, links=no; ), sometimes known as the World Court, is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN). It settles disputes between states in accordan ...

(ICJ) against the United States. Nicaragua stated that the Contras were completely created and managed by the U.S. Although this claim was rejected, the court found overwhelming and undeniable evidence of a very close relationship between the Contras and the United States. The U.S. was found to have had a very large role in providing financial support, training, weapons, and other logistical support to the Contras over a lengthy period of time, and that this support was essential to the Contras.

In the same year, the ICJ ordered the United States to stop mining

Mining is the extraction of valuable minerals or other geological materials from the Earth, usually from an ore body, lode, vein, seam, reef, or placer deposit. The exploitation of these deposits for raw material is based on the econom ...

Nicaraguan harbors, and respect Nicaraguan sovereignty. A few months later, the court ruled that it did have jurisdiction

Jurisdiction (from Latin 'law' + 'declaration') is the legal term for the legal authority granted to a legal entity to enact justice. In federations like the United States, areas of jurisdiction apply to local, state, and federal levels.

J ...

in the case, contrary to what the U.S. had argued. The ICJ found that the U.S. had encouraged violations of international humanitarian law

International humanitarian law (IHL), also referred to as the laws of armed conflict, is the law that regulates the conduct of war ('' jus in bello''). It is a branch of international law that seeks to limit the effects of armed conflict by pr ...

by assisting paramilitary actions in Nicaragua. The court also criticized the production of a manual on psychological warfare by the U.S. and its dissemination of the Contras. The manual, amongst other things, provided advice on rationalizing the killing of civilians, and on targeted murder. The manual also included an explicit description of the use of "implicit terror."

Having initially argued that the ICJ lacked jurisdiction in the case, the United States withdrew from the proceedings in 1985. The court eventually ruled in favor of Nicaragua, and judged that the United States was required to pay reparations for its violation of International law. The U.S. used its veto on the United Nations Security Council

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN) and is charged with ensuring international peace and security, recommending the admission of new UN members to the General Assembly, ...

to block the enforcement of the ICJ judgement, and thereby prevented Nicaragua from obtaining any compensation. "Appraisals of the ICJ's Decision. Nicaragua vs United States (Merits)."

Kosovo Liberation Army

The FR Yugoslav authorities regarded the ethnic AlbanianKosovo Liberation Army

The Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA; , UÇK) was an ethnic Albanian separatist militia that sought the separation of Kosovo

Kosovo ( sq, Kosova or ; sr-Cyrl, Косово ), officially the Republic of Kosovo ( sq, Republika e Kosovës, ...

(KLA) as a terrorist

Terrorism, in its broadest sense, is the use of criminal violence to provoke a state of terror or fear, mostly with the intention to achieve political or religious aims. The term is used in this regard primarily to refer to intentional violen ...

group, using a web.archive.org copy of 2 April 2007 although many European governments did not. In February 1998, U.S. President Bill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton (né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. He previously served as governor of Arkansas from 1979 to 1981 and again ...

's special envoy to the Balkans, Robert Gelbard, condemned both the actions of the Yugoslav government and of the KLA, and described the KLA as "without any questions, a terrorist group".The Kosovo Liberation Army: Does Clinton Policy Support Group with Terror, Drug Ties? From 'Terrorists' to 'Partners', presentation of the Republican Policy Committee to the U.S. Senate, 31 March 1999.Terrorist Groups and Political Legitimacy

Council on Foreign Relations. UN resolution 1160 took a similar stance. At first, NATO had stressed that KLA was "the main initiator of the violence" and that it had "launched what appears to be a deliberate campaign of provocation".. The United States (and NATO) directly supported the KLA. The CIA funded, trained and supplied the KLA (as they had earlier trained and supplied the

Bosnian Army

The Armed Forces of Bosnia and Herzegovina ( sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Oružane snage Bosne i Hercegovine, OSBiH, Оружане снаге Босне и Херцеговине, ОСБИХ) is the official military force of Bosnia and Herz ...

). As disclosed to ''The Sunday Times

''The Sunday Times'' is a British newspaper whose circulation makes it the largest in Britain's quality press market category. It was founded in 1821 as ''The New Observer''. It is published by Times Newspapers Ltd, a subsidiary of News UK, whi ...

'' by CIA sources, "American intelligence agents have admitted they helped to train the Kosovo Liberation Army before NATO's bombing of Yugoslavia". In 1999, a retired colonel said that KLA forces had been trained in Albania by former US military working for MPRI.

James Bissett

James Byron Bissett is a Canadian former diplomat. He was High Commissioner to Trinidad and Tobago and later Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary to Yugoslavia, Albania, and Bulgaria.

Career

James Bissett joined the Canadian govern ...

, Canadian Ambassador to Yugoslavia, Bulgaria and Albania, wrote in 2001 that media reports indicated that "as early as 1998, the Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

assisted by the British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

Special Air Service

The Special Air Service (SAS) is a special forces unit of the British Army. It was founded as a regiment in 1941 by David Stirling and in 1950, it was reconstituted as a corps. The unit specialises in a number of roles including counter-te ...

were arming and training Kosovo Liberation Army members in Albania to foment armed rebellion in Kosovo. ... The hope was that with Kosovo in flames NATO could intervene ...". According to Tim Judah

Tim Judah (born 31 March 1962) is a British writer, reporter and political analyst for ''The Economist''. Judah has written several books on the geopolitics of the Balkans, mainly focusing on Serbia and Kosovo.

Early life

Tim Judah was born in ...

, KLA representatives had already met with American, British, and Swiss intelligence agencies in 1996, and possibly "several years earlier".

After the war, the KLA was transformed into the Kosovo Protection Corps, which worked alongside NATO forces patrolling the province.Council on Foreign Relations

The Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) is an American think tank specializing in U.S. foreign policy and international relations. Founded in 1921, it is a nonprofit organization that is independent and nonpartisan. CFR is based in New York Ci ...

Terrorist Groups and Political Legitimacy

16 March 2006, prepared by Michael Moran In the following years, however, an ethnic Albanian insurgency emerged in southern Serbia (1999–2001) and in Macedonia (2001). The EU condemned what it described as the "extremism" and use of "illegal terrorist actions" by the group active in southern Serbia. Since the war, many of the KLA leaders have been active in the political leadership of the

Republic of Kosovo

Kosovo ( sq, Kosova or ; sr-Cyrl, Косово ), officially the Republic of Kosovo ( sq, Republika e Kosovës, links=no; sr, Република Косово, Republika Kosovo, links=no), is a international recognition of Kosovo, partiall ...

.

Syrian Civil War

TheUnited States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

has provided extensive lethal and non-lethal aid to many Syrian militant groups fighting against the Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

n government, an ally of Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

, during the Syrian Civil War. The Syrian government has directly accused the United States of sponsoring terrorism in Syria. The United States government was also criticized by Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

for its silence following the beheading of a child by the Islamist group Nour al-Din al-Zenki, a group that is a recipient of US military aid and is accused of many war crimes by Amnesty International

Amnesty International (also referred to as Amnesty or AI) is an international non-governmental organization focused on human rights, with its headquarters in the United Kingdom. The organization says it has more than ten million members and s ...

.

Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan

Recep Tayyip Erdoğan (born 26 February 1954) is a Turkish politician serving as the 12th and current president of Turkey since 2014. He previously served as prime minister of Turkey from 2003 to 2014 and as mayor of Istanbul from 1994 to ...

has also accused the United States of supporting ISIS

Isis (; ''Ēse''; ; Meroitic: ''Wos'' 'a''or ''Wusa''; Phoenician: 𐤀𐤎, romanized: ʾs) was a major goddess in ancient Egyptian religion whose worship spread throughout the Greco-Roman world. Isis was first mentioned in the Old Kin ...

in Syria, claiming Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with a small portion on the Balkan Peninsula ...

has evidence of U.S. support for ISIS through pictures, photos, and videos, without further elaborating on said evidence or providing any.

An investigation by journalists Phil Sands and Suha Maayeh revealed that rebels supplied with weapons from the Military Operations Command in Amman

Amman (; ar, عَمَّان, ' ; Ammonite: 𐤓𐤁𐤕 𐤏𐤌𐤍 ''Rabat ʻAmān'') is the capital and largest city of Jordan, and the country's economic, political, and cultural center. With a population of 4,061,150 as of 2021, Amman is ...

sold a portion of them to local arms dealers, often to raise cash to pay additional fighters. Some MOC-supplied weapons were sold to Bedouin

The Bedouin, Beduin, or Bedu (; , singular ) are nomadic Arabs, Arab tribes who have historically inhabited the desert regions in the Arabian Peninsula, North Africa, the Levant, and Mesopotamia. The Bedouin originated in the Syrian Desert ...

traders referred to locally as "The Birds" in Lajat

The Lajat (/ ALA-LC: ''al-Lajāʾ''), also spelled ''Lejat'', ''Lajah'', ''el-Leja'' or ''Laja'', is the largest lava field in southern Syria, spanning some 900 square kilometers. Located about southeast of Damascus, the Lajat borders the Hau ...

, a volcanic plateau northeast of Daraa

Daraa ( ar, دَرْعَا, Darʿā, Levantine Arabic: , also Darʿā, Dara’a, Deraa, Dera'a, Dera, Derʿā and Edrei; means "''fortress''", compare Dura-Europos) is a city in southwestern Syria, located about north of the border with Jord ...

, Syria. According to rebel forces, the Bedouins would then trade the weapons to ISIL, who would place orders using the encrypted WhatsApp

WhatsApp (also called WhatsApp Messenger) is an internationally available freeware, cross-platform, centralized instant messaging (IM) and voice-over-IP (VoIP) service owned by American company Meta Platforms (formerly Facebook). It allows use ...

messaging service. Two rebel commanders and a United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

weapons monitoring organization maintain that MOC–supplied weapons have made their way to ISIL forces.

Another study conducted by private company

A privately held company (or simply a private company) is a company whose shares and related rights or obligations are not offered for public subscription or publicly negotiated in the respective listed markets, but rather the company's stock is ...

Conflict Armament Research Conflict Armament Research (CAR) is a UK-based investigative organization that tracks the supply of conventional weapons, ammunition, and related military materiel (such as IEDs) into conflict-affected areas. Established in 2011, CAR specialises in ...

at the behest of the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational union, supranational political union, political and economic union of Member state of the European Union, member states that are located primarily in Europe, Europe. The union has a total area of ...

and Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit