Union Movement on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

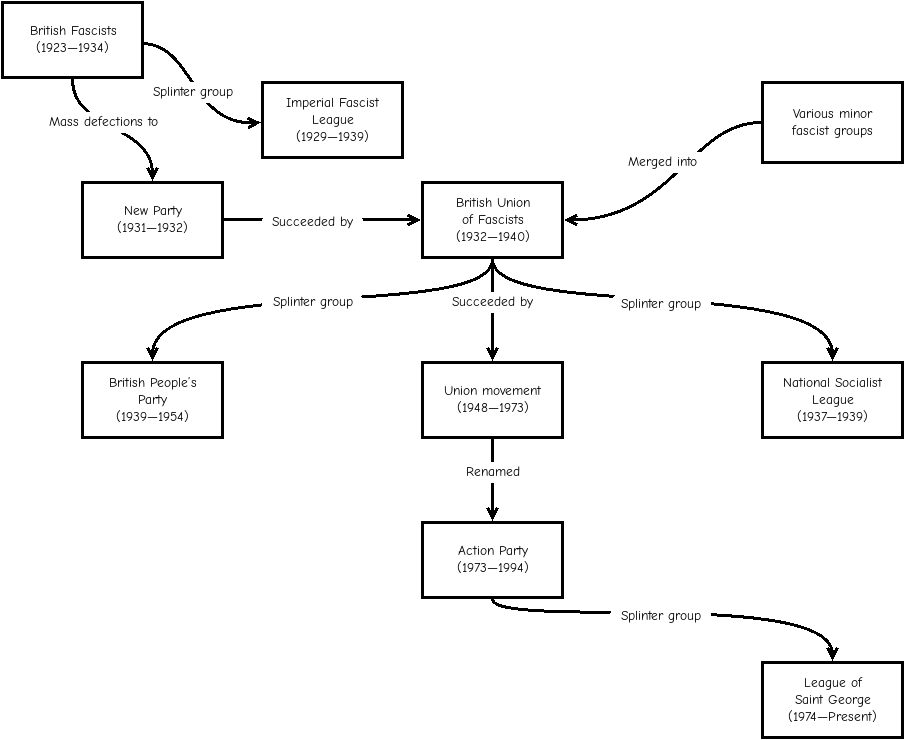

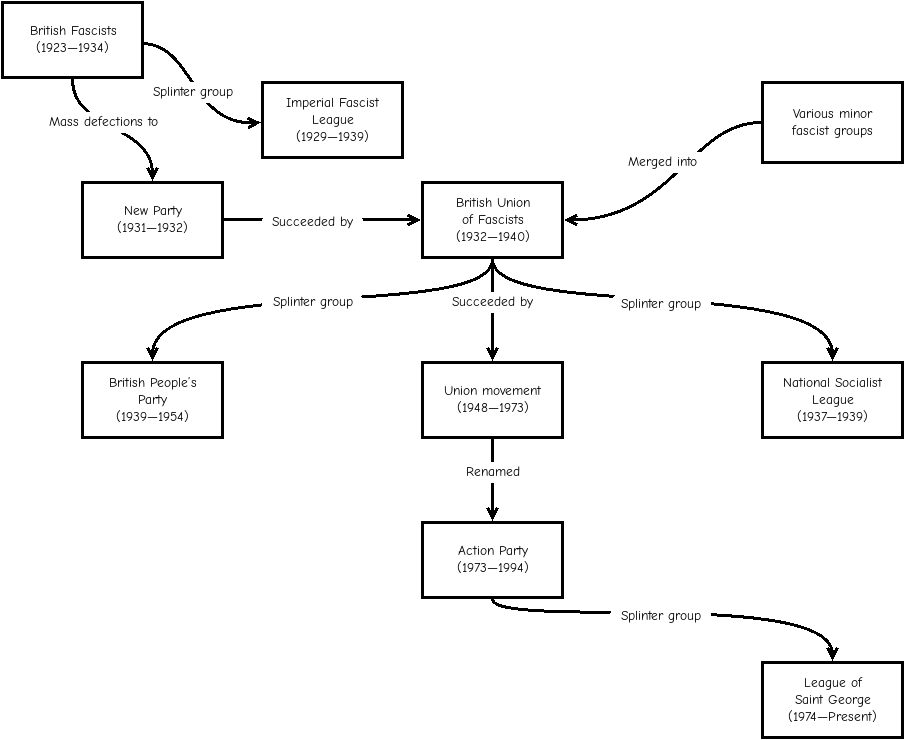

The Union Movement (UM) was a

After the release of interned fascists at the end of the

After the release of interned fascists at the end of the

Union Movement on OswaldMosley.com

* ttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RRS4NR_BZ1w British Pathe film footage of Union Movement marches and rallies in London and Manchester {{Authority control Defunct political parties in the United Kingdom Oswald Mosley Political parties established in 1948 Political parties disestablished in 1973 Neo-fascist parties Fascist parties in the United Kingdom Eurofederalism Far-right political parties in the United Kingdom

far-right

Far-right politics, also referred to as the extreme right or right-wing extremism, are political beliefs and actions further to the right of the left–right political spectrum than the standard political right, particularly in terms of being ...

political party

A political party is an organization that coordinates candidates to compete in a particular country's elections. It is common for the members of a party to hold similar ideas about politics, and parties may promote specific ideological or p ...

founded in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

by Oswald Mosley. Before the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

, Mosley's British Union of Fascists

The British Union of Fascists (BUF) was a British fascist political party formed in 1932 by Oswald Mosley. Mosley changed its name to the British Union of Fascists and National Socialists in 1936 and, in 1937, to the British Union. In 1939, f ...

(BUF) had wanted to concentrate trade within the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

, but the Union Movement attempted to stress the importance of developing a European nationalism, rather than a narrower country-based nationalism

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a in-group and out-group, group of peo ...

. That has caused the UM to be characterised as an attempt by Mosley to start again in his political life by embracing more democratic and international policies than those with which he had previously been associated. The UM has been described as ''post-fascist'' by former members such as Robert Edwards, the founder of the pro-Mosley ''European Action'', a British pressure group.

Mosley's postwar activity

Having been the leader of the BUF in the 1930s, Mosley was expected to return to lead the far right. However, he remained out of the immediate postwar political arena, instead turned to writing and published his first work, ''My Answer'' (1946) in which he argued that he had been a patriot who had been unjustly punished by his internment underDefence Regulation 18B

Defence Regulation 18B, often referred to as simply 18B, was one of the Defence Regulations used by the British Government during and before the Second World War. The complete name for the rule was Regulation 18B of the Defence (General) Regula ...

. In it and his 1947 sequel, ''The Alternative'', Mosley began to argue for a much-closer integration between the nations of Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

, the beginning of his ' Europe a Nation' campaign, which sought a strong united Europe as a counterbalance to the growing power of the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

and the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

.

Europe a Nation

Mosley perceived a linear growth withinBritish history

The British Isles have witnessed intermittent periods of competition and cooperation between the people that occupy the various parts of Great Britain, the Isle of Man, Ireland, the Bailiwick of Guernsey, the Bailiwick of Jersey and ...

and saw Europe a Nation as the culmination of that destiny. Therefore, he argued it to be "part of an organic process of British history" since Britain had united into one nation and that it was Britain's national destiny to unite the whole continent.

He further envisaged a three-tiered system of government, headed by an elected European government, to organise defence and the corporatist

Corporatism is a collectivist political ideology which advocates the organization of society by corporate groups, such as agricultural, labour, military, business, scientific, or guild associations, on the basis of their common interests. The ...

economy. The continuation of national governments and a collection of local governments were still seen as necessary for the sake of independent identities.

Mosley's ideas were not new since concepts of a Nation Europa

''Nation Europa'' (also called ''Nation und Europa'') was a far-right monthly magazine, published in Germany. It was founded in 1951 and was based in Coburg until its closure in 2009. It is also the name of the publishing house that developed th ...

and Eurafrika

Eurafrica (a portmanteau of "Europe" and "Africa"), refers to the originally German idea of strategic partnership between Africa and Europe. In the decades before World War II, German supporters of European integration advocated a merger of Af ...

(the same idea but with parts of north Africa included as natural sectors of Europe's traditional sphere of influence, an idea that Mosley himself felt had some merit) were already growing in Germany's postwar underground. Also, Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in ...

's Italian Social Republic

The Italian Social Republic ( it, Repubblica Sociale Italiana, ; RSI), known as the National Republican State of Italy ( it, Stato Nazionale Repubblicano d'Italia, SNRI) prior to December 1943 but more popularly known as the Republic of Salò ...

had returned to fascism's roots with an attempt at a corporatist economic system during its brief existence. Nonetheless, Mosley was the first to express the ideas in English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ...

, and it came as no surprise when he returned to proper political activism in 1948. Those plans were to form the basis for the policy programme of the Union Movement.

Formation of party

After the release of interned fascists at the end of the

After the release of interned fascists at the end of the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

, a number of far-right groups were formed. They were often virulently anti-Semitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

and tried to capitalise on the violent events taking place in Mandatory Palestine

Mandatory Palestine ( ar, فلسطين الانتدابية '; he, פָּלֶשְׂתִּינָה (א״י) ', where "E.Y." indicates ''’Eretz Yiśrā’ēl'', the Land of Israel) was a geopolitical entity established between 1920 and 1948 ...

. Large meetings were organised in Jewish areas of East London

East or Orient is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from west and is the direction from which the Sun rises on the Earth.

Etymology

As in other languages, the word is formed from the ...

and elsewhere, which were often violently broken up by antifascist groups such as the 43 Group

The 43 Group was an English anti-fascist group set up by Jewish ex-servicemen after the Second World War. They did this when, upon returning to London, they encountered British fascist organisations such as Jeffrey Hamm's British League of Ex ...

. Fifty-one separate groups were united under Mosley's leadership in the Union Movement (UM), launched at a meeting in Farringdon Hall, London, in 1948. The four main groups were Jeffrey Hamm

Edward Jeffrey Hamm (15 September 1915 – 4 May 1992) was a leading British fascist and supporter of Oswald Mosley. Although a minor figure in Mosley's prewar British Union of Fascists, Hamm became a leading figure after the Second World War and ...

's British League of Ex-Servicemen and Women

The British League of Ex-Servicemen and Women (BLESMAW) was a British ex-service organisation that became associated with far-right politics both during and after the Second World War.

Origins

The group had its origins in 1937, when James Taylor s ...

, Anthony Gannon's Imperial Defence League, Victor Burgess's Union of British Freedom and Horace Gowing and Tommy Moran

Thomas P. Moran was a leading member of the British Union of Fascists and a close associate of Oswald Mosley. Initially a miner, Moran later became a qualified engineer. He joined the Royal Air Force at 17 and later served in the Royal Naval Reserv ...

's Sons of St George, all of which were led by ex-BUF men. Another early member was Francis Parker Yockey, an American who had come to England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

to seek Mosley's help to publish his written work. Yockey briefly headed up the UM's European Contact Section, although he left after a dispute with Mosley.

The Union Movement was also known for its attempts to recruit Irish people

The Irish ( ga, Muintir na hÉireann or ''Na hÉireannaigh'') are an ethnic group and nation native to the island of Ireland, who share a common history and culture. There have been humans in Ireland for about 33,000 years, and it has bee ...

living in Britain, and Mosley wrote a pamphlet in 1948, ''Ireland's Right to Unite when entering European Union''. There were also links between the UM and the Irish nationalist and pro-fascist party Ailtirí na hAiséirghe

Ailtirí na hAiséirghe (, meaning "Architects of the Resurrection") was a minor fascist political party in Ireland, founded by Gearóid Ó Cuinneagáin in March 1942.

(''Architects of the Resurrection''), and Mosley wrote articles for its newspaper '' Aiséirghe''.

Mosley remained a critic of liberal democracy

Liberal democracy is the combination of a liberal political ideology that operates under an indirect democratic form of government. It is characterized by elections between multiple distinct political parties, a separation of powers into ...

, and the UM instead extolled a strong executive that people could endorse or reject through regular referendums, with an independent judiciary Judicial independence is the concept that the judiciary should be independent from the other branches of government. That is, courts should not be subject to improper influence from the other branches of government or from private or partisan inter ...

in place to appoint replacements in the event of a rejection. In 1948 the party marched 1,500 supporters through Camden and went on to contest the following year's local elections in London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

. However, outside Shoreditch

Shoreditch is a district in the East End of London in England, and forms the southern part of the London Borough of Hackney. Neighbouring parts of Tower Hamlets are also perceived as part of the area.

In the 16th century, Shoreditch was an imp ...

and Bethnal Green

Bethnal Green is an area in the East End of London northeast of Charing Cross. The area emerged from the small settlement which developed around the Green, much of which survives today as Bethnal Green Gardens, beside Cambridge Heath Road. By ...

, where they polled 15.7% and 7.7% respectively in the wards contested, the UM performed very poorly and secured no representation. The Union Movement then declined as a political party, and attendance at meetings dwindled until it was negligible.''Archive Hour'', BBC Radio 4, first broadcast 19 April 2008. Disillusioned by the stern opposition that the UM faced and his style of street politics being exposed as somewhat passé, in 1951 Mosley went into self-imposed exile in Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel, the Irish Sea, and St George's Channel. Ireland is the s ...

.

The member F.B. Price-Heywood was elected as a councillor in Grasmere, Lake District

The Lake District, also known as the Lakes or Lakeland, is a mountainous region in North West England. A popular holiday destination, it is famous for its lakes, forests, and mountains (or '' fells''), and its associations with William Wordswor ...

, Cumbria

Cumbria ( ) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in North West England, bordering Scotland. The county and Cumbria County Council, its local government, came into existence in 1974 after the passage of the Local Government Act 1972. ...

, during the 1953 local elections, but it was a rare success for the party, and the UM gained no parliamentary seats.

The Union Movement published several weekly newspapers and monthly magazines including ''Union'', ''Action

Action may refer to:

* Action (narrative), a literary mode

* Action fiction, a type of genre fiction

* Action game, a genre of video game

Film

* Action film, a genre of film

* ''Action'' (1921 film), a film by John Ford

* ''Action'' (1980 fil ...

'' (also the title of the prewar weekly newspaper of the New Party and the British Union of Fascists

The British Union of Fascists (BUF) was a British fascist political party formed in 1932 by Oswald Mosley. Mosley changed its name to the British Union of Fascists and National Socialists in 1936 and, in 1937, to the British Union. In 1939, f ...

), ''Attack'', ''Alternative'', ''East London Blackshirt'', ''The European'' and ''National European''.

Racial tensions and rise of party

After theBritish Nationality Act 1948

The British Nationality Act 1948 was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom on British nationality law which defined British nationality by creating the status of "Citizen of the United Kingdom and Colonies" (CUKC) as the sole national ci ...

, there was a great increase in immigration, particularly from the Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. Historically, it has been synonymous with "republic". The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the ...

and the colonies. In the early 1950s, immigration was estimated at 8,000–10,000 per year, but it had grown to 35,000 per year by 1957. Perceptions of the new migrant workers were frequently stereotypical, but the Conservative Party

The Conservative Party is a name used by many political parties around the world. These political parties are generally right-wing though their exact ideologies can range from center-right to far-right.

Political parties called The Conservative P ...

, despite the private opinions of some of its members, was loath to make a political issue out of it for fear of being seen as gutter politicians. Disturbances occurred in 1958 in Notting Hill

Notting Hill is a district of West London, England, in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Notting Hill is known for being a cosmopolitan and multicultural neighbourhood, hosting the annual Notting Hill Carnival and Portobello Road Ma ...

after a Mosley rally and in Nottingham

Nottingham ( , locally ) is a city and unitary authority area in Nottinghamshire, East Midlands, England. It is located north-west of London, south-east of Sheffield and north-east of Birmingham. Nottingham has links to the legend of Robi ...

with clashes between racial groups, a new phenomenon in Britain.

The new uncertainties revitalised the UM, and Mosley re-emerged to stand as a candidate in the 1959 general election in Kensington North, which included Notting Hill, his first parliamentary election since 1931. Mosley made immigration his campaign issue and combined calls for assisted repatriation

Repatriation is the process of returning a thing or a person to its country of origin or citizenship. The term may refer to non-human entities, such as converting a foreign currency into the currency of one's own country, as well as to the pro ...

with stories regarding criminality

In ordinary language, a crime is an unlawful act punishable by a state or other authority. The term ''crime'' does not, in modern criminal law, have any simple and universally accepted definition,Farmer, Lindsay: "Crime, definitions of", in Ca ...

and sexual deviance of black people, a common theme of the time. The 8.1% share of the vote that he secured was a personal humiliation for a man who still hoped that he would be called to serve someday as the British prime minister

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister advises the sovereign on the exercise of much of the royal prerogative, chairs the Cabinet and selects its ministers. As moder ...

. However, the UM was as a whole buoyed by the immigration question, which it saw as the next big issue in British politics.

In April 1965, Mosley attempted to prove that he and the UM were not racist by forming an "Associate Movement" for ethnic minorities who agreed with his policies, including the financially-assisted repatriation of immigrants to their homelands of origin. The group was led by an Indian solicitor and an African airline pilot but was short-lived.

Final days

Along with his domestic politics, Mosley continued to work towards his goal of Europe a Nation and in 1962 attended a conference inVenice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

at which he helped to form a National Party of Europe, along with Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

's Reichspartei, the Mouvement d'Action Civique, and Jeune Europe of Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to ...

and the Italian Social Movement

The Italian Social Movement ( it, Movimento Sociale Italiano, MSI) was a neo-fascist political party in Italy. A far-right party, it presented itself until the 1990s as the defender of Italian fascism's legacy, and later moved towards national ...

(MSI). Adopting the slogan "Progress - Solidarity - Unity", the movement aimed to work closely for a closer unity of European states, but in the end, little came of it as only the MSI enjoyed any success domestically. The group replaced the earlier European Social Movement in which Mosley had also been involved. The Union Movement itself did not play an active role in Europe, although it helped to set in motion co-operation between like-minded groups across Europe, which continued with the European National Front

European National Front (ENF) was a coordinating structure of European ultranationalist

Ultranationalism or extreme nationalism is an extreme form of nationalism in which a country asserts or maintains detrimental hegemony, supremacy, or ot ...

.

Mosley stood again in the 1966 election, this time in the Shoreditch and Finsbury constituency. However, gaining only 4.6% of the vote, Mosley effectively departed the scene thereafter, although he remained the official UM leader until 1973. The increasingly marginalised UM carried on into the 1970s and still advocated Europe A Nation but had no real influence and failed to capture support for its policies.

A brief revival seemed possible after the UM became the Action Party in 1973, the name under which it fought six seats at the Greater London Council election. Under the leadership of Jeffrey Hamm

Edward Jeffrey Hamm (15 September 1915 – 4 May 1992) was a leading British fascist and supporter of Oswald Mosley. Although a minor figure in Mosley's prewar British Union of Fascists, Hamm became a leading figure after the Second World War and ...

, the party hoped for something of a revival although it was damaged severely in 1974 when a leading member, Keith Thompson, and his followers split to form the League of Saint George, a non-party movement that they claimed was the true continuation of Mosley's ideas. With a sizeable chunk of its membership long since lost to the National Front, the Action Party gave up electoral politics and in 1978 became the Action Society, which acted as a publishing house rather than a political party.Boothroyd, D. ''The History of British Political Parties'' Politico's Publishing: 2001, p. 3 The group continued until Hamm's death in 1994, when the funding of Mosley's widow, Diana Mitford

Diana, Lady Mosley (''née'' Freeman-Mitford; 17 June 191011 August 2003) was one of the Mitford sisters. In 1929 she married Bryan Walter Guinness, heir to the barony of Moyne, with whom she was part of the Bright Young Things social group o ...

, was withdrawn. The Action Society was then wound up – this represented the final end of the Union Movement.

Election results

House of Commons

In popular culture

The 1980s ITV television series ''Shine on Harvey Moon

''Shine on, Harvey Moon'' is a British television series made by Witzend Productions and Central Television for ITV from 8 January 1982 to 23 August 1985 and briefly revived in 1995 by Meridian Broadcasting.

This generally light-hearted serie ...

'' features members of Mosley's Union Movement. It was created by the writers Laurence Marks and Maurice Gran who would later produce the Channel 4

Channel 4 is a British free-to-air public broadcast television network operated by the state-owned Channel Four Television Corporation. It began its transmission on 2 November 1982 and was established to provide a fourth television service ...

mini-series '' Mosley'' broadcast in 1998.

See also

Well-known members

* John Bean * Victor Burgess *Jeffrey Hamm

Edward Jeffrey Hamm (15 September 1915 – 4 May 1992) was a leading British fascist and supporter of Oswald Mosley. Although a minor figure in Mosley's prewar British Union of Fascists, Hamm became a leading figure after the Second World War and ...

* Neil Francis Hawkins

* Diana Mitford

Diana, Lady Mosley (''née'' Freeman-Mitford; 17 June 191011 August 2003) was one of the Mitford sisters. In 1929 she married Bryan Walter Guinness, heir to the barony of Moyne, with whom she was part of the Bright Young Things social group o ...

* Tommy Moran

Thomas P. Moran was a leading member of the British Union of Fascists and a close associate of Oswald Mosley. Initially a miner, Moran later became a qualified engineer. He joined the Royal Air Force at 17 and later served in the Royal Naval Reserv ...

* Max Mosley

Max Rufus Mosley (13 April 1940 – 23 May 2021) was a British racing driver, lawyer, and president of the Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile (FIA), a non-profit association which represents the interests of motoring organisations and ...

* Oswald Mosley

* Robert Row

* Keith Thompson

* Alexander Raven Thomson

Alexander Raven Thomson (3 December 1899 – 30 October 1955), usually referred to as Raven, was a Scottish politician and philosopher. He joined the British Union of Fascists in 1933 and remained a follower of Oswald Mosley for the rest of his ...

* John G. Wood

Related groups and concepts

*British Union of Fascists

The British Union of Fascists (BUF) was a British fascist political party formed in 1932 by Oswald Mosley. Mosley changed its name to the British Union of Fascists and National Socialists in 1936 and, in 1937, to the British Union. In 1939, f ...

* Europe a Nation

* League of Saint George

* History of British fascism since 1945

* Friends of Oswald Mosley

References

Bibliography

* Eatwell, R. (2003) ''Fascism: A History'', Pimlico * Mosley, Oswald (1970) ''My Life'', Nelson Press * Mosley, Oswald (1958) ''Europe: Faith and Plan'', Euphorion Books * Skidelsky, Robert (1975) ''Oswald Mosley'',Macmillan

MacMillan, Macmillan, McMillen or McMillan may refer to:

People

* McMillan (surname)

* Clan MacMillan, a Highland Scottish clan

* Harold Macmillan, British statesman and politician

* James MacMillan, Scottish composer

* William Duncan MacMillan ...

* Thurlow, R. (1998) ''Fascism in Britain'', I.B. Tauris

* Macklin, Graham (2007) ''Very Deeply Dyed in Black: Sir Oswald Mosley and the Resurrection of British Fascism after 1945'', I.B. Tauris

External links

Union Movement on OswaldMosley.com

* ttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RRS4NR_BZ1w British Pathe film footage of Union Movement marches and rallies in London and Manchester {{Authority control Defunct political parties in the United Kingdom Oswald Mosley Political parties established in 1948 Political parties disestablished in 1973 Neo-fascist parties Fascist parties in the United Kingdom Eurofederalism Far-right political parties in the United Kingdom