Ukawsaw Gronniosaw on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Ukawsaw Gronniosaw (c. 1705 – 28 September 1775), ''The Chester Chronicle, or Commercial Intelligencer'', Monday 2 October 1775. also known as James Albert, was an enslaved African man who is considered the first published African in Britain. Gronniosaw is known for his 1772 narrative autobiography ''A Narrative of the Most Remarkable Particulars in the Life of James Albert Ukawsaw Gronniosaw, an African Prince, as Related by Himself'', which was the first

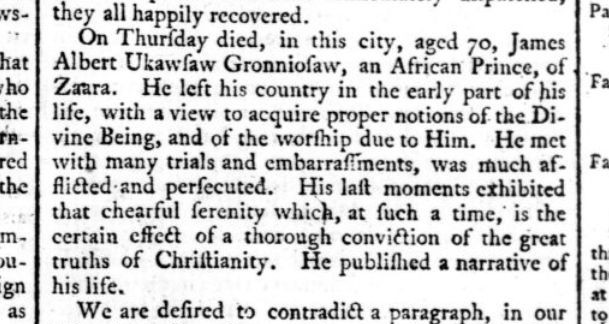

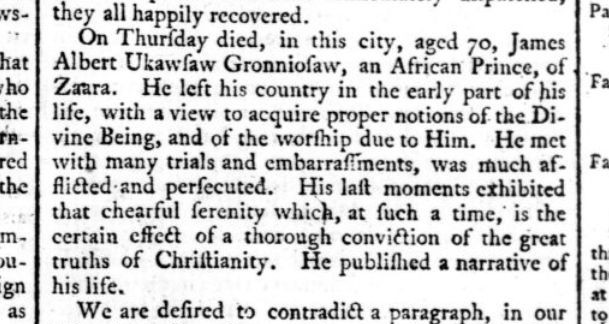

Gronniosaw's ''Narrative'' concludes with its author still living in Kidderminster, having "appear dto be turn'd sixty"; for a long time, nothing was known of his later life. However, at some point during the late twentieth century, an obituary for Gronniosaw was discovered in the '' Chester Chronicle''. The article, from 2 October 1775, reads:

Gronniosaw's ''Narrative'' concludes with its author still living in Kidderminster, having "appear dto be turn'd sixty"; for a long time, nothing was known of his later life. However, at some point during the late twentieth century, an obituary for Gronniosaw was discovered in the '' Chester Chronicle''. The article, from 2 October 1775, reads:

''A Narrative of the Most Remarkable Particulars in the Life of James Albert Ukawsaw Gronniosaw, an African Prince, as Related by Himself''

Bath: Printed by W. Gye, 1770. {{DEFAULTSORT:Gronniosaw, Ukawsaw 1710 births 1775 deaths 18th-century American slaves 18th-century Nigerian people Barbadian slaves Black British former slaves Black British history Black British writers British autobiographers Converts to Protestantism from pagan religions American freedmen Nigerian autobiographers Nigerian emigrants to the United States Nigerian expatriates in the United Kingdom People who wrote slave narratives

slave narrative

The slave narrative is a type of literary genre involving the (written) autobiographical accounts of enslaved Africans, particularly in the Americas. Over six thousand such narratives are estimated to exist; about 150 narratives were published as s ...

published in England. His autobiography recounted his early life in present-day Nigeria

Nigeria ( ), , ig, Naìjíríyà, yo, Nàìjíríà, pcm, Naijá , ff, Naajeeriya, kcg, Naijeriya officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf o ...

, his enslavement, and his eventual emancipation.

Life

Gronniosaw was born in Bornu (now north-easternNigeria

Nigeria ( ), , ig, Naìjíríyà, yo, Nàìjíríà, pcm, Naijá , ff, Naajeeriya, kcg, Naijeriya officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf o ...

) in 1705. He said that he was doted on as the grandson of the king of Zaara. At the age of 15, he was taken by a Gold Coast

Gold Coast may refer to:

Places Africa

* Gold Coast (region), in West Africa, which was made up of the following colonies, before being established as the independent nation of Ghana:

** Portuguese Gold Coast (Portuguese, 1482–1642)

** Dutch G ...

ivory merchant and sold to a Dutch captain for two yards of check cloth. He was bought by an American in Barbados

Barbados is an island country in the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies, in the Caribbean region of the Americas, and the most easterly of the Caribbean Islands. It occupies an area of and has a population of about 287,000 (2019 estimate) ...

, who took him to New York and resold him for £50 to "Mr. Freelandhouse, a very gracious, good Minister." Freelandhouse is presumed to be the Dutch Reformed Church

The Dutch Reformed Church (, abbreviated NHK) was the largest Christian denomination in the Netherlands from the onset of the Protestant Reformation in the 16th century until 1930. It was the original denomination of the Dutch Royal Family and ...

minister, Theodorus Jacobus Frelinghuysen

Theodorus Jacobus Frelinghuysen ( – ) was a Dutch-American Dutch Reformed minister, theologian and the progenitor of the Frelinghuysen family in the United States of America. Frelinghuysen is most remembered for his religious contribution ...

, based in New Jersey.

There Gronniosaw was taught to read and was brought up as a Christian. Gronniosaw said in his autobiography that he wanted to return to his family in Africa, but Frelinghuysen denied this request and told him to focus on the Christian faith. During his time with Frelinghuysen, Gronniosaw attempted suicide, distressed by his perceived failings as a Christian. When the minister died, he freed Gronniosaw in his will. The young man worked for the minister's widow, and subsequently their orphans, but all died within four years.

Planning to go to England, where he expected to meet other pious people like the Frelinghuysens, Gronniosaw travelled to the Caribbean, where he enlisted as a cook with a privateer

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

, and later as a soldier in the 28th Regiment of Foot

The 28th (North Gloucestershire) Regiment of Foot was a line infantry regiment of the British Army, raised in 1694. Under the Childers Reforms it amalgamated with the 61st (South Gloucestershire) Regiment of Foot to form the Gloucestershire Re ...

to earn money for the journey. He served in Martinique

Martinique ( , ; gcf, label=Martinican Creole, Matinik or ; Kalinago: or ) is an island and an overseas department/region and single territorial collectivity of France. An integral part of the French Republic, Martinique is located in ...

and Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

, before obtaining his discharge and sailing to England.

At first he settled in Portsmouth, but, when his landlady swindled him out of most of his savings, was forced to seek his fortune in London. There he married a young English widow, Betty, a weaver. She already had a child and bore him at least two more. She lost her job because of the financial depression and industrial unrest, and moved to Colchester. There they were saved from starvation by Osgood Hanbury (a Quaker lawyer and grandfather of the abolitionist Thomas Fowell Buxton), who employed Gronniosaw in building work. Moving to Norwich

Norwich () is a cathedral city and district of Norfolk, England, of which it is the county town. Norwich is by the River Wensum, about north-east of London, north of Ipswich and east of Peterborough. As the seat of the See of Norwich, with ...

, Gronniosaw and his family again fell on hard times, as the building trades were largely seasonal. Once again, they were saved by the kindness of a Quaker, Henry Gurney (coincidentally, the grandfather of Fowell Buxton's wife, Hannah Gurney) who paid their rent arrears. A daughter died and was refused burial by the local clergy on the grounds that she was not baptised. One minister at last offered to allow her to be buried in the churchyard, but he would not read the burial service.

After pawning all their possessions, the family moved to Kidderminster

Kidderminster is a large market and historic minster town and civil parish in Worcestershire, England, south-west of Birmingham and north of Worcester. Located north of the River Stour and east of the River Severn, in the 2011 census, it ha ...

, where Betty supported them by working again as a weaver. On Christmas Day 1771, Gronniosaw had their remaining children, Mary Albert (aged six), Edward Albert (aged four), and newborn Samuel Albert, baptised in the Old Independent Meeting House in Kidderminster by Benjamin Fawcett

Benjamin Fawcett (December 1808, in Bridlington, East Riding of Yorkshire – January 1893) was an English nineteenth century woodblock colour printer.

Life

The son of a ship's master, Fawcett was apprenticed at age 14 for seven years to Wil ...

, a Dissenting minister and associate of Selina Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon

Selina Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon (24 August 1707 – 17 June 1791) was an English religious leader who played a prominent part in the religious revival of the 18th century and the Methodist movement in England and Wales. She founded an ...

and a major figure in Calvinistic Methodism

The Presbyterian Church of Wales ( cy, Eglwys Bresbyteraidd Cymru), also known as Calvinistic Methodist Church (), is a denomination of Protestant Christianity in Wales.

History

The church was born out of the Welsh Methodist revival and the ...

. At around the same time, Gronniosaw received a letter and a charitable donation from Hastings herself. On 3 January 1772, he responded by thanking her for her 'favour', which arrived 'at a time of great necessity', and explained that he had just returned from 'Mrs Marlowe's' in nearby Leominster

Leominster ( ) is a market town in Herefordshire, England, at the confluence of the River Lugg and its tributary the River Kenwater. The town is north of Hereford and south of Ludlow in Shropshire. With a population of 11,700, Leominster i ...

, 'were I was shewed kindness to from my Christian friends'. On 25 June 1774, Gronniosaw's fifth child, James Albert junior was baptised, again by Fawcett.

Shortly after his arrival in Kidderminster, Gronniosaw began work on his life story, with the help of an amanuensis from Leominster, possibly the 'Mrs Marlowe' he had mentioned in his letter to Hastings. Gronniosaw's ''Narrative'' has been studied by scholars as a groundbreaking work by an African in English. It is the first known slave narrative

The slave narrative is a type of literary genre involving the (written) autobiographical accounts of enslaved Africans, particularly in the Americas. Over six thousand such narratives are estimated to exist; about 150 narratives were published as s ...

published in England and received wide attention, with multiple printings and editions at the time.

Gronniosaw's ''Narrative'' concludes with its author still living in Kidderminster, having "appear dto be turn'd sixty"; for a long time, nothing was known of his later life. However, at some point during the late twentieth century, an obituary for Gronniosaw was discovered in the '' Chester Chronicle''. The article, from 2 October 1775, reads:

Gronniosaw's ''Narrative'' concludes with its author still living in Kidderminster, having "appear dto be turn'd sixty"; for a long time, nothing was known of his later life. However, at some point during the late twentieth century, an obituary for Gronniosaw was discovered in the '' Chester Chronicle''. The article, from 2 October 1775, reads:On ThursdayThe burial register for the Church of England parish church of St Oswald, Chester - a church which occupied the south transept of8 September Events Pre-1600 * 617 – Battle of Huoyi: Li Yuan defeats a Sui dynasty army, opening the path to his capture of the imperial capital Chang'an and the eventual establishment of the Tang dynasty. *1100 – Election of Antipope Theodo ...died, in this city, aged 70, James Albert Ukawsaw Gronniosaw, an African Prince, of Zaara. He left his country in the early part of his life, with a view to acquire proper notions of the Divine Being, and of the worship due to Him. He met with many trials and embarrassments, was much afflicted and persecuted. His last moments exhibited that chearful 'sic''serenity which, at such a time, is the certain effect of a thorough conviction of the great truths of Christianity. He published a narrative of his life.

Chester Cathedral

Chester Cathedral is a Church of England cathedral and the mother church of the Diocese of Chester. It is located in the city of Chester, Cheshire, England. The cathedral, formerly the abbey church of a Benedictine monastery dedicated to Saint ...

from 1448 to 1881 - includes an entry from 28 September 1775 for "James Albert (a Blackm n", giving his age as 70. "James Albert (a Blackm)"; Chester St Oswald Burial Record, 28 September 1775. Gronniosaw's grave has not been identified.

The autobiography

Gronniosaw's autobiography was produced inKidderminster

Kidderminster is a large market and historic minster town and civil parish in Worcestershire, England, south-west of Birmingham and north of Worcester. Located north of the River Stour and east of the River Severn, in the 2011 census, it ha ...

in 1772. It is entitled ''A Narrative of the Most remarkable Particulars in the Life of James Albert Ukawsaw Gronniosaw, an African Prince, As related by himself.'' The title page explains that it was "committed to paper by the elegant pen of a young LADY of the town of LEOMINSTER." It is the first slave narrative by an African in the English language

English is a West Germanic language of the Indo-European language family, with its earliest forms spoken by the inhabitants of early medieval England. It is named after the Angles, one of the ancient Germanic peoples that migrated to the ...

, a genre related to the literature of enslaved persons who later gained freedom. Published in Bath, Somerset, in December 1772, it gives a vivid account of Gronniosaw's life, from his leaving home to his enslavement in Africa by a native king, through a period of being enslaved, to his struggles with poverty as a free man in Colchester

Colchester ( ) is a city in Essex, in the East of England. It had a population of 122,000 in 2011. The demonym is Colcestrian.

Colchester occupies the site of Camulodunum, the first major city in Roman Britain and its first capital. Colch ...

and Kidderminster. He was attracted to this last town because it was at one time the home of Richard Baxter

Richard Baxter (12 November 1615 – 8 December 1691) was an English Puritan church leader, poet, hymnodist, theologian, and controversialist. Dean Stanley called him "the chief of English Protestant Schoolmen". After some false starts, he ...

, a 17th-century Nonconformist minister whom Gronniosaw had learned to admire.

The preface was written by the Reverend Walter Shirley, cousin to Selina Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon, who was a patron of the Calvinist wing of Methodism

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a group of historically related denominations of Protestant Christianity whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's br ...

. He interprets Gronniosaw's experience of enslavement and his being transported from Bornu to New York as an example of Calvinist predestination and election.

Scholar Henry Louis Gates Jr.

Henry Louis "Skip" Gates Jr. (born September 16, 1950) is an American literary critic, professor, historian, and filmmaker, who serves as the Alphonse Fletcher University Professor and Director of the Hutchins Center for African and African A ...

has noted that Gronniosaw's narrative was different from later slave narratives, which generally criticised slavery as an institution. In his account, Gronniosaw referred to his "white-skinned sister," said that he had been willing to leave Africa because his family believed in many deities instead of one almighty God (which he learned more about under Christianity), and suggested that he became happier as he assimilated to white English society, through clothing but mostly via language. In addition, he described another black servant at his master's house as a "devil." Gates has concluded that the narrative does not have an anti-slavery view, as was ubiquitous in subsequent slave narratives.Henry Louis Gates, Jr

Henry Louis "Skip" Gates Jr. (born September 16, 1950) is an American literary critic, professor, historian, and filmmaker, who serves as the Alphonse Fletcher University Professor and Director of the Hutchins Center for African and African Amer ...

, ''The Signifying Monkey

''The Signifying Monkey: A Theory of Afro-American Literary Criticism'' is a work of literary criticism and theory by the American scholar Henry Louis Gates Jr. first published in 1988. The book traces the folkloric origins of the African-Americ ...

'', Oxford University Press

Oxford University Press (OUP) is the university press of the University of Oxford. It is the largest university press in the world, and its printing history dates back to the 1480s. Having been officially granted the legal right to print books ...

, 1988, pp. 133–40.

Until the recent discovery of the 1775 obituary and a manuscript

A manuscript (abbreviated MS for singular and MSS for plural) was, traditionally, any document written by hand – or, once practical typewriters became available, typewritten – as opposed to mechanically printed or reproduced in ...

letter written by Gronniosaw to Hastings, the ''Narrative'' was the only significant source of information for his life.

See also

*Black British elite

The Black elite is any elite, either political or economic in nature, that is made up of people who identify as of Black African descent. In the Western World, it is typically distinct from other national elites, such as the United Kingdom's ari ...

, the class Gronniosaw belonged to.

References

Notes

Additional sources

*Echero, Michael. "Theologizing 'Underneath the Tree': an African topos in Ukawsaw Gronniosaw, William Blake, and William Cole". ''Research in African Literatures''. 23.4 (Winter 1992). 51–58. *Harris, Jennifer. "Seeing the Light: Re-Reading James Albert Ukawsaw Gronniosaw". ''English Language Notes'' 42.4, 2005: 43–57.External links

* * *''A Narrative of the Most Remarkable Particulars in the Life of James Albert Ukawsaw Gronniosaw, an African Prince, as Related by Himself''

Bath: Printed by W. Gye, 1770. {{DEFAULTSORT:Gronniosaw, Ukawsaw 1710 births 1775 deaths 18th-century American slaves 18th-century Nigerian people Barbadian slaves Black British former slaves Black British history Black British writers British autobiographers Converts to Protestantism from pagan religions American freedmen Nigerian autobiographers Nigerian emigrants to the United States Nigerian expatriates in the United Kingdom People who wrote slave narratives