USS Santee (1855) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

USS ''Santee'' was a wooden-hulled, three-masted sailing

Refitted at the

Refitted at the

In 1866, she became a gunnery ship and was used by midshipmen to master the art of naval gunnery. About the same time, the frigate began to be used as a

In 1866, she became a gunnery ship and was used by midshipmen to master the art of naval gunnery. About the same time, the frigate began to be used as a

Journal of the Officer of the Day, U.S.S. ''Santee'', 1864, MS 123

an

Journal of the Officer of the Day, U.S.S. ''Santee'', 1865-1866, MS 124

held by Special Collections & Archives, Nimitz Library at the United States Naval Academy {{DEFAULTSORT:Santee Ships of the Union Navy Ships built in Kittery, Maine Sailing frigates of the United States Navy Gunboats of the United States Navy American Civil War patrol vessels of the United States United States Naval Academy Training ships of the United States Navy 1855 ships Shipwrecks of the Maryland coast Ship fires Shipwrecks of the Massachusetts coast Maritime incidents in 1912 Maritime incidents in 1913

frigate

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied somewhat.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed and ...

of the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

. She was the first U.S. Navy ship to be so named and was one of its last sailing frigate

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied somewhat.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed and ...

s in service. She was acquired by the Union Navy

), (official)

, colors = Blue and gold

, colors_label = Colors

, march =

, mascot =

, equipment =

, equipment_label ...

at the start of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, outfitted with heavy guns and a crew of 480, and was assigned as a gunboat

A gunboat is a naval watercraft designed for the express purpose of carrying one or more guns to bombard coastal targets, as opposed to those military craft designed for naval warfare, or for ferrying troops or supplies.

History Pre-steam ...

in the Union blockade

The Union blockade in the American Civil War was a naval strategy by the United States to prevent the Confederacy from trading.

The blockade was proclaimed by President Abraham Lincoln in April 1861, and required the monitoring of of Atlantic ...

of the Confederate States

The Confederate States of America (CSA), commonly referred to as the Confederate States or the Confederacy was an unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United States that existed from February 8, 1861, to May 9, 1865. The Confeder ...

. She later became a training ship

A training ship is a ship used to train students as sailors. The term is mostly used to describe ships employed by navies to train future officers. Essentially there are two types: those used for training at sea and old hulks used to house classr ...

then a barracks ship

A barracks ship or barracks barge or berthing barge, or in civilian use accommodation vessel or accommodation ship, is a ship or a non-self-propelled barge containing a superstructure of a type suitable for use as a temporary barracks for sai ...

for the U.S. Naval Academy

The United States Naval Academy (US Naval Academy, USNA, or Navy) is a United States Service academies, federal service academy in Annapolis, Maryland. It was established on 10 October 1845 during the tenure of George Bancroft as Secretary of ...

.

Service history

Rated at 44 guns, she was laid down in 1820 by thePortsmouth Navy Yard

The Portsmouth Naval Shipyard, often called the Portsmouth Navy Yard, is a United States Navy shipyard in Kittery on the southern boundary of Maine near the city of Portsmouth, New Hampshire.

Founded in 1800, PNS is U.S. Navy's oldest continuou ...

, but due to a shortage of funds, she long remained uncompleted on the stocks. She was finally launched on 16 February 1855, but not commissioned until 9 June 1861, Captain Henry Eagle in command. ''Santee'' departed Portsmouth, New Hampshire

Portsmouth is a city in Rockingham County, New Hampshire, United States. At the 2020 census it had a population of 21,956. A historic seaport and popular summer tourist destination on the Piscataqua River bordering the state of Maine, Portsmou ...

on 20 June 1861, stopped at Hampton Roads, Virginia

Hampton Roads is the name of both a body of water in the United States that serves as a wide channel for the James, Nansemond and Elizabeth rivers between Old Point Comfort and Sewell's Point where the Chesapeake Bay flows into the Atlantic O ...

to load ammunition, and resumed her voyage to the Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico ( es, Golfo de México) is an oceanic basin, ocean basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, largely surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north and northwest by the Gulf Coast of ...

on 10 July. On 8 August, the frigate

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied somewhat.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed and ...

captured the schooner

A schooner () is a type of sailing vessel defined by its rig: fore-and-aft rigged on all of two or more masts and, in the case of a two-masted schooner, the foremast generally being shorter than the mainmast. A common variant, the topsail schoon ...

''C. P. Knapp'' in the gulf some 350 miles south of Pensacola

Pensacola () is the westernmost city in the Florida Panhandle, and the county seat and only incorporated city of Escambia County, Florida, United States. As of the 2020 United States census, the population was 54,312. Pensacola is the principal ci ...

and escorted the blockade runner

A blockade runner is a merchant vessel used for evading a naval blockade of a port or strait. It is usually light and fast, using stealth and speed rather than confronting the blockaders in order to break the blockade. Blockade runners usuall ...

to that port. On 27 October, ''Santee'' took her second prize, ''Delta'', off Galveston

Galveston ( ) is a coastal resort city and port off the Southeast Texas coast on Galveston Island and Pelican Island in the U.S. state of Texas. The community of , with a population of 47,743 in 2010, is the county seat of surrounding Galvesto ...

; the hermaphrodite brig

A brigantine is a two-masted sailing vessel with a fully square-rigged foremast and at least two sails on the main mast: a square topsail and a Gaff rig, gaff sail mainsail (behind the mast). The main mast is the second and taller of the two mas ...

had attempted to slip into Galveston with a cargo of salt from Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a popul ...

.

Shortly before midnight on 7 November, boats left the frigate and entered Galveston Bay

Galveston Bay ( ) is a bay in the western Gulf of Mexico along the upper coast of Texas. It is the seventh-largest estuary in the United States, and the largest of seven major estuaries along the Texas Gulf Coast. It is connected to the Gulf of ...

hoping to capture and burn the Confederate armed steamer, ''General Rusk''. However, in attempting to avoid detection, the boats ran aground. Since he had lost the advantage of surprise, the expedition's commander, Lt. James Edward Jouett

Rear Admiral James Edward Jouett (7 February 1826 – 30 September 1902), known as "Fighting Jim Jouett of the American Navy", was an officer in the United States Navy during the Mexican–American War and the American Civil War. His father was M ...

, cancelled his plans to attack ''General Rusk'' and turned his attention to the chartered Confederate lookout vessel, ''Royal Yacht''. After a desperate hand-to-hand fight, he captured ''Royal Yacht''s crew, set the armed schooner afire, and retired to ''Santee'' with about a dozen prisoners. During the action, one man from the frigate was killed and two of her officers and six of her men were wounded, one mortally. A young 15-year-old sailor named James Henry Carpenter was wounded in the thigh and mentioned in dispatches due to his actions. Carpenter would become ''Santee''s acting Master's mate

Master's mate is an obsolete rating which was used by the Royal Navy, United States Navy and merchant services in both countries for a senior petty officer who assisted the master. Master's mates evolved into the modern rank of Sub-Lieutenant in t ...

and would serve again on ''Santee'' when she served as a school ship for the United States Naval Academy

The United States Naval Academy (US Naval Academy, USNA, or Navy) is a federal service academy in Annapolis, Maryland. It was established on 10 October 1845 during the tenure of George Bancroft as Secretary of the Navy. The Naval Academy ...

.

(Note: Much of the history of James Henry Carpenter came from his second wife's pension files) Another of ''Santee''s sailors, George H. Bell, was awarded the Medal of Honor

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is the United States Armed Forces' highest military decoration and is awarded to recognize American soldiers, sailors, marines, airmen, guardians and coast guardsmen who have distinguished themselves by acts of valor. ...

for his part in the action.

On 30 December, after a five or six-mile chase on boats from ''Santee,'' they captured 14-ton Confederate schooner, ''Garonne''. Captain Eagle stripped the prize for use as a lighter

A lighter is a portable device which creates a flame, and can be used to ignite a variety of items, such as cigarettes, gas lighter, fireworks, candles or campfires. It consists of a metal or plastic container filled with a flammable liquid or c ...

. In January 1862, when the Union naval force in the Gulf of Mexico was divided into two squadrons, ''Santee'' was assigned to Flag Officer David Farragut

David Glasgow Farragut (; also spelled Glascoe; July 5, 1801 – August 14, 1870) was a flag officer of the United States Navy during the American Civil War. He was the first rear admiral, vice admiral, and admiral in the United States Navy. Fa ...

's new West Gulf Blockading Squadron

The Union blockade in the American Civil War was a naval strategy by the United States to prevent the Confederate States of America, Confederacy from trading.

The blockade was proclaimed by President Abraham Lincoln in April 1861, and required ...

. Under the new organization, ''Santee'' continued to blockade the Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish language, Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2 ...

coast, primarily off Galveston, until summer. Then, because scurvy

Scurvy is a disease resulting from a lack of vitamin C (ascorbic acid). Early symptoms of deficiency include weakness, feeling tired and sore arms and legs. Without treatment, decreased red blood cells, gum disease, changes to hair, and bleeding ...

had weakened the frigate's crew and the enlistments of many of her sailors had expired, the ship sailed north. She reached Boston, Massachusetts on 22 August and was decommissioned on 4 September.

Refitted at the

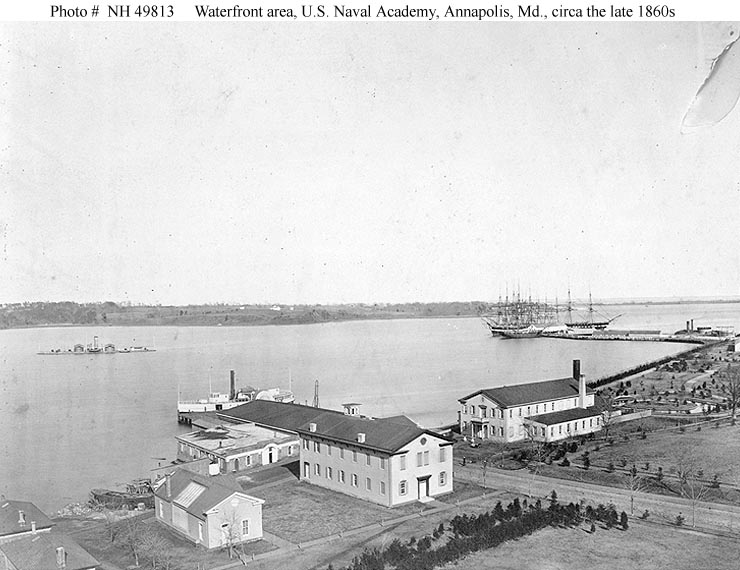

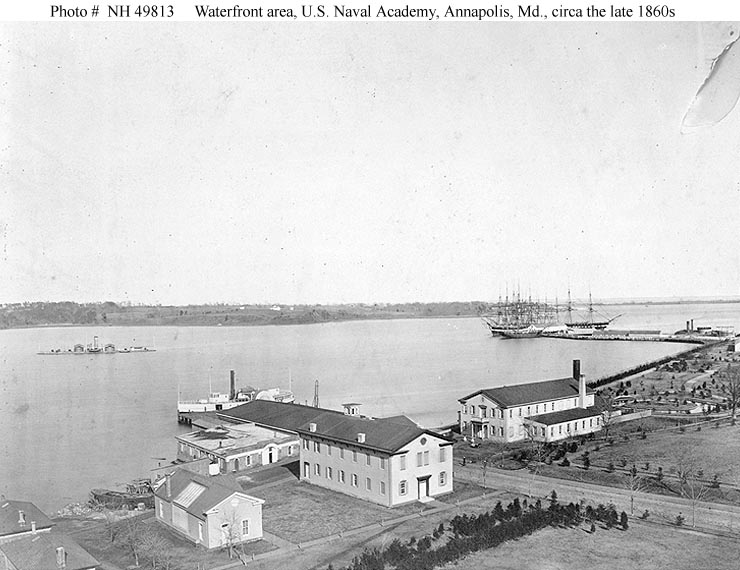

Refitted at the Boston Navy Yard

The Boston Navy Yard, originally called the Charlestown Navy Yard and later Boston Naval Shipyard, was one of the oldest shipbuilding facilities in the United States Navy. It was established in 1801 as part of the recent establishment of t ...

, the ship was recommissioned there exactly a month later and sailed for Newport, Rhode Island

Newport is an American seaside city on Aquidneck Island in Newport County, Rhode Island. It is located in Narragansett Bay, approximately southeast of Providence, Rhode Island, Providence, south of Fall River, Massachusetts, south of Boston, ...

, to serve as a school ship

A training ship is a ship used to train students as sailors. The term is mostly used to describe ships employed by navies to train future officers. Essentially there are two types: those used for training at sea and old hulks used to house classr ...

at the Naval Academy, which had been moved there from Annapolis, Maryland

Annapolis ( ) is the capital city of the U.S. state of Maryland and the county seat of, and only incorporated city in, Anne Arundel County. Situated on the Chesapeake Bay at the mouth of the Severn River, south of Baltimore and about east o ...

, for security during the Civil War. At Newport, midshipmen

A midshipman is an officer of the lowest rank, in the Royal Navy, United States Navy, and many Commonwealth navies. Commonwealth countries which use the rank include Canada (Naval Cadet), Australia, Bangladesh, Namibia, New Zealand, South Afr ...

lived, studied, and attended classes in frigates ''Santee'' and as they prepared for positions of leadership in the Union Navy. After the close of the Civil War, the Naval Academy returned to Annapolis, Maryland, and ''Santee'', carrying midshipmen, sailed for that port and moored near Fort Severn

Fort Severn, in present-day Annapolis, Maryland, was built in 1808 on the same site as an earlier American Revolutionary War fort of 1776. Although intended to guard Annapolis harbor from British attack during the War of 1812, it never saw ac ...

on 2 August 1865. There, she continued her duty as school ship which she had performed at Newport.

Post-war career

In 1866, she became a gunnery ship and was used by midshipmen to master the art of naval gunnery. About the same time, the frigate began to be used as a

In 1866, she became a gunnery ship and was used by midshipmen to master the art of naval gunnery. About the same time, the frigate began to be used as a barracks ship

A barracks ship or barracks barge or berthing barge, or in civilian use accommodation vessel or accommodation ship, is a ship or a non-self-propelled barge containing a superstructure of a type suitable for use as a temporary barracks for sai ...

for midshipmen being punished and for new fourthclassmen receiving their first taste of Navy life.

Before dawn on 2 April 1912, after a half a century of duty as an educator, ''Santee'' sank at her mooring. Efforts to refloat the frigate proved unsuccessful. She was sold to Henry A. Hitner's Sons Company Henry A. Hitner's Sons Company owned an iron works in Philadelphia.

The company was established by Henry Adam Hitner and incorporated on 28 December 1906. It purchased many retired United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the mar ...

, of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

, on 2 August 1912, the anniversary of her arrival at Annapolis. After six months of effort, she was finally raised; and, on 8 May 1913, ''Santee'' departed the Severn River under tow and proceeded to Boston, where she was burned for the copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu (from la, cuprum) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkis ...

and brass

Brass is an alloy of copper (Cu) and zinc (Zn), in proportions which can be varied to achieve different mechanical, electrical, and chemical properties. It is a substitutional alloy: atoms of the two constituents may replace each other with ...

in her hull.

See also

*List of sailing frigates of the United States Navy

This is a list of sailing frigates of the United States Navy. Frigates were the backbone of the early Navy, although the list shows that many suffered unfortunate fates.

The sailing frigates of the United States built from 1797 on were unique i ...

References

External links

*Journal of the Officer of the Day, U.S.S. ''Santee'', 1864, MS 123

an

Journal of the Officer of the Day, U.S.S. ''Santee'', 1865-1866, MS 124

held by Special Collections & Archives, Nimitz Library at the United States Naval Academy {{DEFAULTSORT:Santee Ships of the Union Navy Ships built in Kittery, Maine Sailing frigates of the United States Navy Gunboats of the United States Navy American Civil War patrol vessels of the United States United States Naval Academy Training ships of the United States Navy 1855 ships Shipwrecks of the Maryland coast Ship fires Shipwrecks of the Massachusetts coast Maritime incidents in 1912 Maritime incidents in 1913