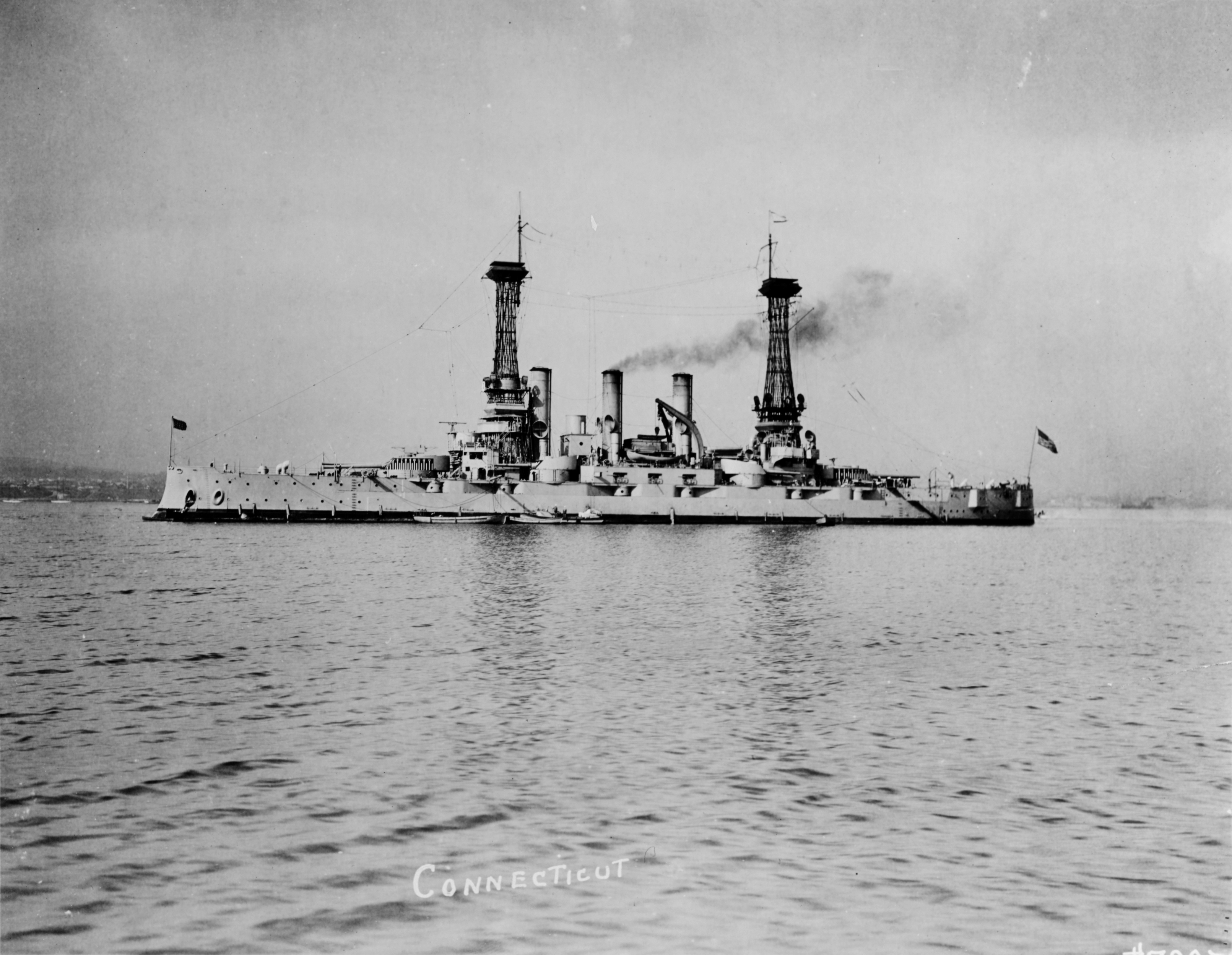

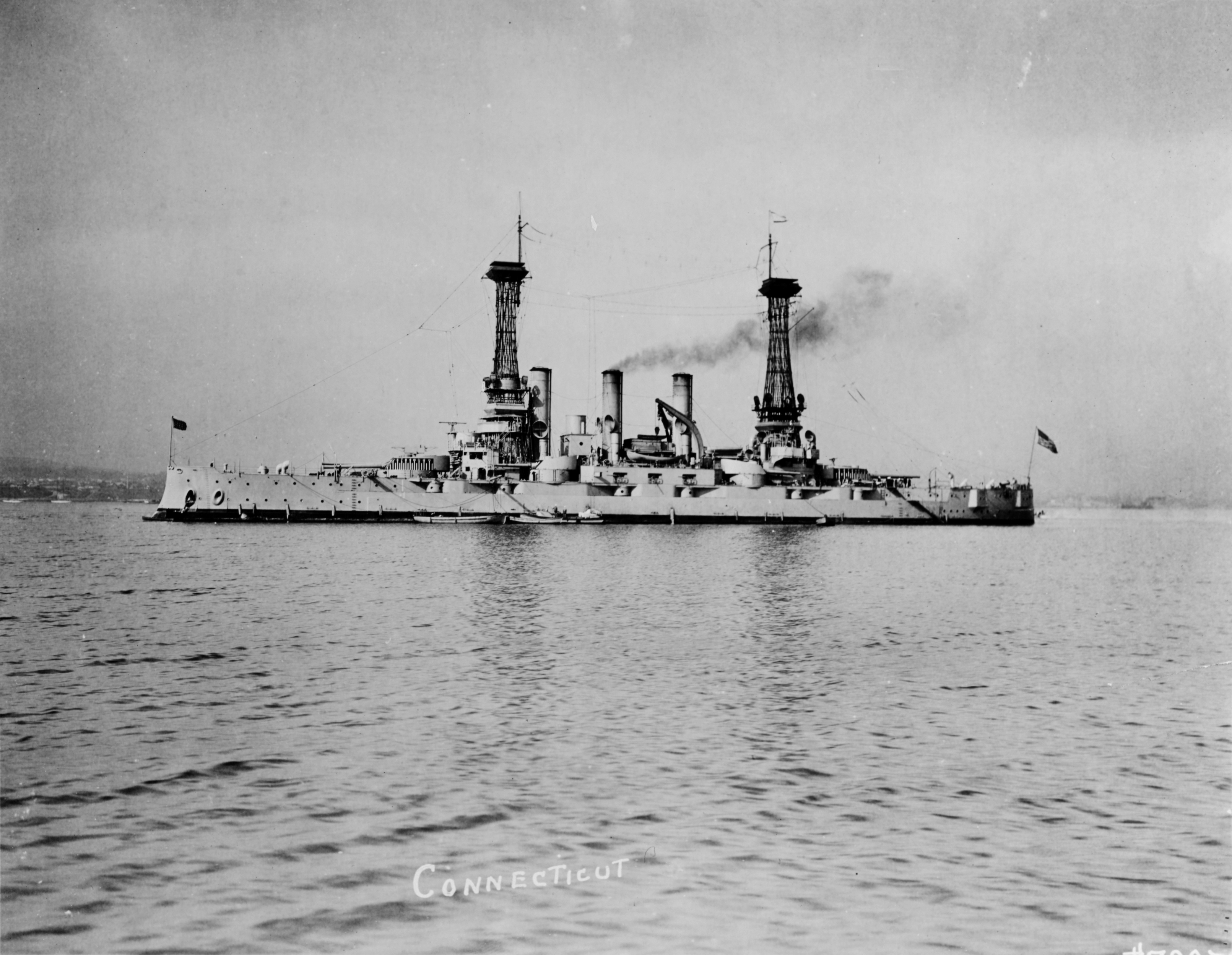

USS Connecticut (BB-18) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

USS ''Connecticut'' (BB-18), the fourth

''Connecticut'' was

''Connecticut'' was

''Connecticut'' was ordered on 1 July 1902.Friedman (1985), p. 46 On 15 October 1902, she was awarded to the

''Connecticut'' was ordered on 1 July 1902.Friedman (1985), p. 46 On 15 October 1902, she was awarded to the  On 21 March, the Navy announced that Swift would be court-martialed for "through negligence, causing a vessel to run upon a rock" and "neglect of duty in regard to the above". Along with the officer of the deck at the time of the accident,

On 21 March, the Navy announced that Swift would be court-martialed for "through negligence, causing a vessel to run upon a rock" and "neglect of duty in regard to the above". Along with the officer of the deck at the time of the accident,

The cruise of the Great White Fleet was conceived as a way to demonstrate American military power, particularly to Japan. Tensions had begun to rise between the United States and Japan after the latter's victory in the

The cruise of the Great White Fleet was conceived as a way to demonstrate American military power, particularly to Japan. Tensions had begun to rise between the United States and Japan after the latter's victory in the  Arriving in Mexico, on 20 March, the fleet underwent three weeks of target practice. Rear Admiral Evans was relieved of command during this time, as he was completely bedridden and in constant pain, on 30 March, ''Connecticut'' set sail north at full speed. She was met two days later by the schooner , which took the admiral to a hospital. ''Connecticut'' traveled back south to rejoin the fleet, and Rear Admiral Charles M. Thomas took Evans's place on ''Connecticut'' as the commander of the fleet, which continued its journey north, bound for

Arriving in Mexico, on 20 March, the fleet underwent three weeks of target practice. Rear Admiral Evans was relieved of command during this time, as he was completely bedridden and in constant pain, on 30 March, ''Connecticut'' set sail north at full speed. She was met two days later by the schooner , which took the admiral to a hospital. ''Connecticut'' traveled back south to rejoin the fleet, and Rear Admiral Charles M. Thomas took Evans's place on ''Connecticut'' as the commander of the fleet, which continued its journey north, bound for  After stopping at

After stopping at

Following her return from the world cruise, ''Connecticut'' continued to serve as flagship of the Atlantic Fleet, interrupted only by a March 1909 overhaul at the New York Navy Yard. After rejoining the fleet, she cruised the East Coast from her base at Norfolk, Virginia. For the rest of 1909, the battleship conducted training and participated in ceremonial observances, such as the

Following her return from the world cruise, ''Connecticut'' continued to serve as flagship of the Atlantic Fleet, interrupted only by a March 1909 overhaul at the New York Navy Yard. After rejoining the fleet, she cruised the East Coast from her base at Norfolk, Virginia. For the rest of 1909, the battleship conducted training and participated in ceremonial observances, such as the  On 22 June 1912, ''Connecticut'' departed Mexican waters for Philadelphia, where she was dry docked for three months of repairs. Upon their completion, ''Connecticut'' conducted gunnery practice off the Virginia Capes. On 23 October, ''Connecticut'' became the flagship of the Fourth Battleship Division. After the division passed in review before Secretary of the Navy

On 22 June 1912, ''Connecticut'' departed Mexican waters for Philadelphia, where she was dry docked for three months of repairs. Upon their completion, ''Connecticut'' conducted gunnery practice off the Virginia Capes. On 23 October, ''Connecticut'' became the flagship of the Fourth Battleship Division. After the division passed in review before Secretary of the Navy

At the close of the war, ''Connecticut'' was assigned to the

At the close of the war, ''Connecticut'' was assigned to the

United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

ship to be named after the state of Connecticut

Connecticut () is the southernmost state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. Its capita ...

, was the lead ship

The lead ship, name ship, or class leader is the first of a series or class of ships all constructed according to the same general design. The term is applicable to naval ships and large civilian vessels.

Large ships are very complex and may ...

of her class of six pre-dreadnought battleship

Pre-dreadnought battleships were sea-going battleships built between the mid- to late- 1880s and 1905, before the launch of in 1906. The pre-dreadnought ships replaced the ironclad battleships of the 1870s and 1880s. Built from steel, protec ...

s. Her keel

The keel is the bottom-most longitudinal structural element on a vessel. On some sailboats, it may have a hydrodynamic and counterbalancing purpose, as well. As the laying down of the keel is the initial step in the construction of a ship, in Br ...

was laid on 10 March 1903; launched on 29 September 1904, ''Connecticut'' was commissioned on 29 September 1906, as the most advanced ship in the US Navy.

''Connecticut'' served as the flagship for the Jamestown Exposition

The Jamestown Exposition was one of the many world's fairs and expositions that were popular in the United States in the early part of the 20th century. Commemorating the 300th anniversary of the founding of Jamestown in the Virginia Colony, it w ...

in mid-1907, which commemorated the 300th anniversary of the founding of the Jamestown colony. She later sailed with the Great White Fleet on a circumnavigation of the Earth to showcase the US Navy's growing fleet of blue-water-capable ships. After completing her service with the Great White Fleet, ''Connecticut'' participated in several flag-waving exercises intended to protect American citizens abroad until she was pressed into service as a troop transport at the end of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

to expedite the return of American Expeditionary Forces

The American Expeditionary Forces (A. E. F.) was a formation of the United States Army on the Western Front of World War I. The A. E. F. was established on July 5, 1917, in France under the command of General John J. Pershing. It fought along ...

from France.

For the remainder of her career, ''Connecticut'' sailed to various places in both the Atlantic and Pacific while training newer recruits to the Navy. However, the provisions of the 1922 Washington Naval Treaty

The Washington Naval Treaty, also known as the Five-Power Treaty, was a treaty signed during 1922 among the major Allies of World War I, which agreed to prevent an arms race by limiting naval construction. It was negotiated at the Washington Nav ...

stipulated that many of the older battleships, ''Connecticut'' among them, would have to be disposed of, so she was decommissioned on 1 March 1923, and sold for scrap on 1 November 1923.

Design

''Connecticut'' was

''Connecticut'' was long overall

__NOTOC__

Length overall (LOA, o/a, o.a. or oa) is the maximum length of a vessel's hull measured parallel to the waterline. This length is important while docking the ship. It is the most commonly used way of expressing the size of a ship, an ...

and had a beam

Beam may refer to:

Streams of particles or energy

*Light beam, or beam of light, a directional projection of light energy

**Laser beam

*Particle beam, a stream of charged or neutral particles

**Charged particle beam, a spatially localized grou ...

of and a draft

Draft, The Draft, or Draught may refer to:

Watercraft dimensions

* Draft (hull), the distance from waterline to keel of a vessel

* Draft (sail), degree of curvature in a sail

* Air draft, distance from waterline to the highest point on a vesse ...

of . She displaced as designed and up to at full load

The displacement or displacement tonnage of a ship is its weight. As the term indicates, it is measured indirectly, using Archimedes' principle, by first calculating the volume of water displaced by the ship, then converting that value into wei ...

. The ship was powered by two-shaft triple-expansion steam engine

A compound steam engine unit is a type of steam engine where steam is expanded in two or more stages.

A typical arrangement for a compound engine is that the steam is first expanded in a high-pressure ''(HP)'' cylinder, then having given up ...

s rated at , with steam provided by twelve coal-fired Babcock & Wilcox boiler

A high pressure watertube boiler (also spelled water-tube and water tube) is a type of boiler in which water circulates in tubes heated externally by the fire. Fuel is burned inside the furnace, creating hot gas which boils water in the steam-gene ...

s ducted into three funnels. The propulsion system generated a top speed of . As built, she was fitted with heavy military masts, but these were quickly replaced by lattice mast

Lattice masts, or cage masts, or basket masts, are a type of observation mast common on United States Navy major warships in the early 20th century. They are a type of hyperboloid structure, whose weight-saving design was invented by the Russian ...

s in 1909. She had a crew of 827 officers and men, though this increased to 881 and later to 896.Gardiner, p. 144

The ship was armed with a main battery

A main battery is the primary weapon or group of weapons around which a warship is designed. As such, a main battery was historically a gun or group of guns, as in the broadsides of cannon on a ship of the line. Later, this came to be turreted ...

of four 12 inch /45 Mark 5 guns in two twin gun turret

A gun turret (or simply turret) is a mounting platform from which weapons can be fired that affords protection, visibility and ability to turn and aim. A modern gun turret is generally a rotatable weapon mount that houses the crew or mechani ...

s on the centerline

Center line, centre line or centerline may refer to:

Sports

* Center line, marked in red on an ice hockey rink

* Centre line (football), a set of positions on an Australian rules football field

* Centerline, a line that separates the service cou ...

, one forward and aft. The secondary battery

A rechargeable battery, storage battery, or secondary cell (formally a type of energy accumulator), is a type of electrical battery which can be charged, discharged into a load, and recharged many times, as opposed to a disposable or pri ...

consisted of eight /45 guns and twelve /45 guns. The 8-inch guns were mounted in four twin turrets amidships

This glossary of nautical terms is an alphabetical listing of terms and expressions connected with ships, shipping, seamanship and navigation on water (mostly though not necessarily on the sea). Some remain current, while many date from the 17th ...

and the 7-inch guns were placed in casemates

A casemate is a fortified gun emplacement or armored structure from which guns are fired, in a fortification, warship, or armoured fighting vehicle.Webster's New Collegiate Dictionary

When referring to antiquity, the term "casemate wall" mea ...

in the hull. For close-range defense against torpedo boat

A torpedo boat is a relatively small and fast naval ship designed to carry torpedoes into battle. The first designs were steam-powered craft dedicated to ramming enemy ships with explosive spar torpedoes. Later evolutions launched variants of ...

s, she carried twenty /50 guns mounted in casemates along the side of the hull and twelve 3-pounder guns. She also carried four 1-pounder guns. As was standard for capital ship

The capital ships of a navy are its most important warships; they are generally the larger ships when compared to other warships in their respective fleet. A capital ship is generally a leading or a primary ship in a naval fleet.

Strategic im ...

s of the period, ''Connecticut'' carried four 21 inch (533 mm) torpedo tube

A torpedo tube is a cylindrical device for launching torpedoes.

There are two main types of torpedo tube: underwater tubes fitted to submarines and some surface ships, and deck-mounted units (also referred to as torpedo launchers) installed aboa ...

s, submerged in her hull on the broadside

Broadside or broadsides may refer to:

Naval

* Broadside (naval), terminology for the side of a ship, the battery of cannon on one side of a warship, or their near simultaneous fire on naval warfare

Printing and literature

* Broadside (comic ...

.

''Connecticut''s main armored belt

Belt armor is a layer of heavy metal vehicle armor, armor plated onto or within the outer hulls of warships, typically on battleships, battlecruisers and cruisers, and aircraft carriers.

The belt armor is designed to prevent projectiles from p ...

was thick over the magazines

A magazine is a periodical publication, generally published on a regular schedule (often weekly or monthly), containing a variety of content. They are generally financed by advertising, purchase price, prepaid subscriptions, or by a combination ...

and the propulsion machinery spaces and elsewhere. The main battery gun turrets had thick faces, and the supporting barbette

Barbettes are several types of gun emplacement in terrestrial fortifications or on naval ships.

In recent naval usage, a barbette is a protective circular armour support for a heavy gun turret. This evolved from earlier forms of gun protectio ...

s had the of armor plating. The secondary turrets had of frontal armor. The conning tower had thick sides.

Service history

Construction

''Connecticut'' was ordered on 1 July 1902.Friedman (1985), p. 46 On 15 October 1902, she was awarded to the

''Connecticut'' was ordered on 1 July 1902.Friedman (1985), p. 46 On 15 October 1902, she was awarded to the New York Naval Shipyard

The Brooklyn Navy Yard (originally known as the New York Navy Yard) is a shipyard and industrial complex located in northwest Brooklyn in New York City, New York (state), New York. The Navy Yard is located on the East River in Wallabout Bay, a ...

. She was laid down

Laying the keel or laying down is the formal recognition of the start of a ship's construction. It is often marked with a ceremony attended by dignitaries from the shipbuilding company and the ultimate owners of the ship.

Keel laying is one o ...

on 10 March 1903,Albertson (2007), p. 35Friedman (1985), p. 419 and launched on 29 September 1904. She was sponsored by Miss Alice B. Welles, granddaughter of Gideon Welles

Gideon Welles (July 1, 1802 – February 11, 1878), nicknamed "Father Neptune", was the United States Secretary of the Navy from 1861 to 1869, a cabinet post he was awarded after supporting Abraham Lincoln in the 1860 election. Although opposed ...

, Secretary of the Navy during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

. A crowd of over 30,000 people attended the launch, as did many of the Navy's ships. The battleships , , , , , , , and were at the ceremony, along with the protected cruiser

Protected cruisers, a type of naval cruiser of the late-19th century, gained their description because an armoured deck offered protection for vital machine-spaces from fragments caused by shells exploding above them. Protected cruisers re ...

s and and the auxiliary cruiser .

Three attempts to sabotage the ship were discovered in 1904. On 31 March, rivets on the keel plates were found bored through. On 14 September, a bolt was found driven into the launching way, where it protruded some . Shortly after ''Connecticut'' was launched on 29 September, a diameter

In geometry, a diameter of a circle is any straight line segment that passes through the center of the circle and whose endpoints lie on the circle. It can also be defined as the longest chord of the circle. Both definitions are also valid fo ...

hole was discovered drilled through a steel keel

The keel is the bottom-most longitudinal structural element on a vessel. On some sailboats, it may have a hydrodynamic and counterbalancing purpose, as well. As the laying down of the keel is the initial step in the construction of a ship, in Br ...

plate.It was estimated that drilling the hole would have taken 20 minutes. See: The ship's watertight compartment

A compartment is a portion of the space within a ship defined vertically between decks and horizontally between bulkheads. It is analogous to a room within a building, and may provide watertight subdivision of the ship's hull important in retaini ...

s and pumps prevented her from sinking, and all damage was repaired. The incidents prompted the Navy to post armed guards at the shipyard, and an overnight watch was kept by a Navy tug manned by Marines

Marines, or naval infantry, are typically a military force trained to operate in littoral zones in support of naval operations. Historically, tasks undertaken by marines have included helping maintain discipline and order aboard the ship (refle ...

who had orders to shoot to kill any unauthorized person attempting to approach the ship.

As ''Connecticut'' was only 55% complete when she was launched, missing most of her upper works, protection, machinery and armament, it was two years before ''Connecticut'' was commissioned on 29 September 1906. Captain William Swift was the first captain of the new battleship. ''Connecticut'' sailed out of New York for the first time on 15 December 1906, becoming the first ship in the US Navy to ever go to sea without a sea trial

A sea trial is the testing phase of a watercraft (including boats, ships, and submarines). It is also referred to as a " shakedown cruise" by many naval personnel. It is usually the last phase of construction and takes place on open water, and ...

. She first journeyed south to the Virginia Capes

The Virginia Capes are the two capes, Cape Charles to the north and Cape Henry to the south, that define the entrance to Chesapeake Bay on the eastern coast of North America.

In 1610, a supply ship learned of the famine at Jamestown when it ...

, where she conducted a variety of training exercises; this was followed by a shakedown cruise and battle practice off Cuba and Puerto Rico.Albertson (2007), p. 36 During the cruise, she participated in a search for the missing steamer ''Ponce''.''Ponce'' was eventually found and towed back to port by a German freighter; the seven passengers were taken off by the Quebec liner ''Bermudian''. See:

On 13 January 1907, ''Connecticut'' ran onto a reef

A reef is a ridge or shoal of rock, coral or similar relatively stable material, lying beneath the surface of a natural body of water. Many reefs result from natural, abiotic processes— deposition of sand, wave erosion planing down rock o ...

while entering the harbor at Culebra Island. The Navy did not release any information about the grounding until press dispatches from San Juan, carrying news of the incident reached the mainland on 23 January. Even then, Navy authorities in San Juan claimed to be ignorant of the situation, and, that same day, the Navy Department itself said that they only knew that Captain Swift thought she had touched bottom and that an examination of the ship's bottom by divers had revealed no damage. The Navy amended this the next day, releasing a statement that ''Connecticut'' had been only slightly damaged and had returned to her shakedown cruise. However, damage to the ship was much more serious than the Navy admitted; in contrast to an official statement saying that ''Connecticut'' had only "touched" the rocks, she actually had run full upon the reef when traversing "a course well marked with buoys" in "broad daylight" and did enough damage to probably require a dry docking. This apparent attempt at a cover-up was enough for the United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washing ...

to consider an official inquiry into the matter.

On 21 March, the Navy announced that Swift would be court-martialed for "through negligence, causing a vessel to run upon a rock" and "neglect of duty in regard to the above". Along with the officer of the deck at the time of the accident,

On 21 March, the Navy announced that Swift would be court-martialed for "through negligence, causing a vessel to run upon a rock" and "neglect of duty in regard to the above". Along with the officer of the deck at the time of the accident, Lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often ...

Harry E. Yarnell, Swift faced a court martial of seven rear admirals, a captain, and a lieutenant. He was sentenced to one year's suspension from duty, later reduced to nine months; after about six months, the sentence was remitted on 24 October. However, he was not assigned command of another ship.

''Connecticut'' steamed back to Hampton Roads after this, arriving on 16 April; when she arrived, Rear Admiral Robley D. Evans, commander of the Atlantic Fleet, transferred his flag from ''Maine'' to ''Connecticut'', making her the flagship of the fleet. President Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

opened the Jamestown Exposition

The Jamestown Exposition was one of the many world's fairs and expositions that were popular in the United States in the early part of the 20th century. Commemorating the 300th anniversary of the founding of Jamestown in the Virginia Colony, it w ...

on 25 April, and ''Connecticut'' was named as the official host of the vessels that were visiting from other countries. Sailors and marines from the ship took part in various events ashore, and foreign dignitaries, along with the governors of Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

and Rhode Island

Rhode Island (, like ''road'') is a state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is the smallest U.S. state by area and the seventh-least populous, with slightly fewer than 1.1 million residents as of 2020, but it ...

, were hosted aboard the ship on 29 April. Evans closed the Exposition on 4 May, on the quarterdeck of ''Connecticut''. On 10 June, ''Connecticut'' joined in the Presidential Fleet Review; she left three days later for an overhaul in the New York Naval Yard

The Brooklyn Navy Yard (originally known as the New York Navy Yard) is a shipyard and industrial complex located in northwest Brooklyn in New York City, New York. The Navy Yard is located on the East River in Wallabout Bay, a semicircular bend ...

. After the overhaul, ''Connecticut'' conducted maneuvers off Hampton Roads, and target practice off Cape Cod. She was ordered back to the New York Naval Yard, once again on 6 September, for a refit that would make her suitable for use as flagship of the Great White Fleet.Albertson (2007), p. 38

Flagship of the Great White Fleet

The cruise of the Great White Fleet was conceived as a way to demonstrate American military power, particularly to Japan. Tensions had begun to rise between the United States and Japan after the latter's victory in the

The cruise of the Great White Fleet was conceived as a way to demonstrate American military power, particularly to Japan. Tensions had begun to rise between the United States and Japan after the latter's victory in the Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War ( ja, 日露戦争, Nichiro sensō, Japanese-Russian War; russian: Ру́сско-япóнская войнá, Rússko-yapónskaya voyná) was fought between the Empire of Japan and the Russian Empire during 1904 and 1 ...

in 1905, particularly over racist opposition to Japanese immigration to the United States. The press in both countries began to call for war, and Roosevelt hoped to use the demonstration of naval might to deter Japanese aggression. ''Connecticut'' left the New York Naval Yard, on 5 December 1907, and arrived the next day in Hampton Roads, where the Great White Fleet would assemble with her as their flagship. After an eight-day period known as "Navy Farewell Week" during which festivities were held for the departing sailors, and all 16 battleships took on full loads of coal, stores, and ammunition, the ships were ready to depart. The battleship captains paid their respects to President Theodore Roosevelt on the presidential yacht , and all the ships weighed anchor and departed at 1000. They passed in review before the President, and then began traveling south.

After steaming past Cape Hatteras

Cape Hatteras is a cape located at a pronounced bend in Hatteras Island, one of the barrier islands of North Carolina.

Long stretches of beach, sand dunes, marshes, and maritime forests create a unique environment where wind and waves shap ...

, the fleet headed for the Caribbean. They approached Puerto Rico, on 20 December, caught sight of Venezuela

Venezuela (; ), officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela ( es, link=no, República Bolivariana de Venezuela), is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many islands and islets in th ...

on 22 December, and later dropped anchor in Port of Spain, the capital of Trinidad

Trinidad is the larger and more populous of the two major islands of Trinidad and Tobago. The island lies off the northeastern coast of Venezuela and sits on the continental shelf of South America. It is often referred to as the southernmos ...

, making the first port visit of the Great White Fleet. With the torpedo boat flotilla that had left Hampton Roads, two weeks previously, and five colliers to fill the coal bunkers of the fleet, Port of Spain had a total of 32 US Navy ships in the harbor, making it " esemblea US Navy base".Albertson (2007), p. 42

After spending Christmas in Trinidad, the ships departed for Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro ( , , ; literally 'River of January'), or simply Rio, is the capital of the state of the same name, Brazil's third-most populous state, and the second-most populous city in Brazil, after São Paulo. Listed by the GaWC as a ...

, on 29 December. A ceremonial Brazilian escort of three cruisers met the task force outside Rio, and "thousands of wildly cheering Brazilians lined the shore"; 10 days of ceremonies, games, and festivities followed, and the stopover was so successful that the visit was the cause of a major boost in US–Brazilian relations.Albertson (2007), p. 43 The fleet left Rio on 22 January 1908, still heading south, this time bound for the coaling stop of Punta Arenas, Chile

Punta Arenas (; historically Sandy Point in English) is the capital city of Chile's southernmost region, Magallanes and Antarctica Chilena. The city was officially renamed as Magallanes in 1927, but in 1938 it was changed back to "Punta Aren ...

.

Four cruisers from Argentina, ''San Martin'', ''Buenos Ayres'', ''9 De Julio'', and ''Pueyrredon'', all under the command of Admiral Hipolito Oliva, sailed to salute the American ships on their way to Chile. The fleet arrived at Punta Arenas, on 1 February, and spent five days in the town of 14,000. Heading north, they followed the coastline of Chile, passing in review of Chilean President Pedro Montt on 14 February, outside Valparaíso

Valparaíso (; ) is a major city, seaport, naval base, and educational centre in the commune of Valparaíso, Chile. "Greater Valparaíso" is the second largest metropolitan area in the country. Valparaíso is located about northwest of Santiago ...

, and they were escorted to Callao, in Peru, by the cruiser ''Coronel Bolognesi'' on 19 and 20 February. Peru's president, José Pardo, came aboard ''Connecticut'' during this time, as Rear Admiral Evans was quite ill and could not go ashore. After taking on coal, the ships steamed for Mexico, on 29 February, passing in review of the cruiser ''Almirante Grau'', which had Pardo embarked, before leaving.Albertson (2007), p. 46

Arriving in Mexico, on 20 March, the fleet underwent three weeks of target practice. Rear Admiral Evans was relieved of command during this time, as he was completely bedridden and in constant pain, on 30 March, ''Connecticut'' set sail north at full speed. She was met two days later by the schooner , which took the admiral to a hospital. ''Connecticut'' traveled back south to rejoin the fleet, and Rear Admiral Charles M. Thomas took Evans's place on ''Connecticut'' as the commander of the fleet, which continued its journey north, bound for

Arriving in Mexico, on 20 March, the fleet underwent three weeks of target practice. Rear Admiral Evans was relieved of command during this time, as he was completely bedridden and in constant pain, on 30 March, ''Connecticut'' set sail north at full speed. She was met two days later by the schooner , which took the admiral to a hospital. ''Connecticut'' traveled back south to rejoin the fleet, and Rear Admiral Charles M. Thomas took Evans's place on ''Connecticut'' as the commander of the fleet, which continued its journey north, bound for California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the m ...

.Albertson (2007), p. 47

On 5 May, Evans returned to ''Connecticut'' in time for the fleet's sailing through the Golden Gate

The Golden Gate is a strait on the west coast of North America that connects San Francisco Bay to the Pacific Ocean. It is defined by the headlands of the San Francisco Peninsula and the Marin Peninsula, and, since 1937, has been spanned by t ...

on 6 May, although he was still in pain.Albertson (2007), p. 48 Over one million people watched the 42-ship fleet sail into the bay.The Great White Fleet was joined by various Pacific Fleet warships and a torpedo boat flotilla for their entrance into the harbor, making the conglomerate of ships the "most powerful concentration of naval might yet gathered in the Western Hemisphere". See: Albertson (2007), p. 47. After a grand parade through San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish for " Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the fourth most populous in California and 17th ...

, a review of the fleet by Secretary of the Navy Victor H. Metcalf

Victor Howard Metcalf (October 10, 1853 – February 20, 1936) was an American politician; he served in President Theodore Roosevelt's cabinet as Secretary of Commerce and Labor, and then as Secretary of the Navy.

Biography

Born in Utica, New ...

, a gala reception, and a farewell address from Evans (who was retiring due to his illness and his age), the fleet left San Francisco, for Seattle

Seattle ( ) is a seaport city on the West Coast of the United States. It is the seat of King County, Washington. With a 2020 population of 737,015, it is the largest city in both the state of Washington and the Pacific Northwest regio ...

, with Rear Admiral Charles Stillman Sperry

Rear Admiral Charles Stillman Sperry (September 3, 1847February 1, 1911) was an officer in the United States Navy.

Born in Brooklyn, New York, Sperry graduated from the Naval Academy in 1866. In November 1898, he became commanding officer of a ...

as commander. The ships all underwent refits before the next leg of the voyage. The fleet left the West Coast again on 7 July, bound for Hawaii, which it reached on 16 July.

Leaving Hawaii, on 22 July, the ships next stopped at Auckland

Auckland (pronounced ) ( mi, Tāmaki Makaurau) is a large metropolitan city in the North Island of New Zealand. The most populous urban area in the country and the fifth largest city in Oceania, Auckland has an urban population of about ...

, Sydney, and Melbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a met ...

. High seas and winds hampered the ships for part of the voyage to New Zealand, but they arrived on 9 August; festivities, parades, balls, and games were staples of the visits to each city. The highlight of the austral visit was a parade of 12,000 US Navy, Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

, and Commonwealth naval and military personnel in front of 250,000 people.

After stopping at

After stopping at Manila

Manila ( , ; fil, Maynila, ), officially the City of Manila ( fil, Lungsod ng Maynila, ), is the capital of the Philippines, and its second-most populous city. It is highly urbanized and, as of 2019, was the world's most densely populate ...

, in the Philippines, the fleet set course for Yokohama

is the second-largest city in Japan by population and the most populous municipality of Japan. It is the capital city and the most populous city in Kanagawa Prefecture, with a 2020 population of 3.8 million. It lies on Tokyo Bay, south of T ...

, Japan. They encountered a typhoon on the way on 12 October, but no ships were lost; the fleet was only delayed 24 hours. After three Japanese men-of-war

The man-of-war (also man-o'-war, or simply man) was a Royal Navy expression for a powerful warship or frigate from the 16th to the 19th century. Although the term never acquired a specific meaning, it was usually reserved for a ship armed w ...

and six merchantmen escorted the Americans in, festivities began. The celebrations culminated in the Uraga, where Commodore

Commodore may refer to:

Ranks

* Commodore (rank), a naval rank

** Commodore (Royal Navy), in the United Kingdom

** Commodore (United States)

** Commodore (Canada)

** Commodore (Finland)

** Commodore (Germany) or ''Kommodore''

* Air commodore ...

Matthew C. Perry

Matthew Calbraith Perry (April 10, 1794 – March 4, 1858) was a commodore of the United States Navy who commanded ships in several wars, including the War of 1812 and the Mexican–American War (1846–1848). He played a leading role in the o ...

had anchored a little more than 50 years prior. The ships then departed on 25 October. After three weeks of exercises in the Philippines' Subic Bay

Subic Bay is a bay on the west coast of the island of Luzon in the Philippines, about northwest of Manila Bay. An extension of the South China Sea, its shores were formerly the site of a major United States Navy facility, U.S. Naval Base Sub ...

, the ships sailed south on 1 December, for Singapore

Singapore (), officially the Republic of Singapore, is a sovereign island country and city-state in maritime Southeast Asia. It lies about one degree of latitude () north of the equator, off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, bor ...

; they did not stop there, however, passing outside the city on 6 December. Continuing on, they stopped at Colombo

Colombo ( ; si, කොළඹ, translit=Koḷam̆ba, ; ta, கொழும்பு, translit=Koḻumpu, ) is the executive and judicial capital and largest city of Sri Lanka by population. According to the Brookings Institution, Colombo m ...

, for coal from 12 to 20 December, before sailing on for the Suez Canal. It took three days for all 16 battleships to traverse the canal, even though it was closed to all other traffic. They then headed for a coaling stop at Port Said, Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Medit ...

, after which the fleet split up into individual divisions to call on different ports in the Mediterranean. The First Division, of which ''Connecticut'' was a part, originally planned to visit Italy, before moving on to Villefranche, but ''Connecticut'' and ''Illinois'' were quickly dispatched to southern Italy, on a humanitarian mission when news of an earthquake reached the fleet. Seamen from the ships helped clear debris and unload supplies from the US Navy refrigerated supply ship ; Admiral Sperry received the personal thanks of King Victor Emmanuel III

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen, which title is also given to the consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contemporary indigenous peoples, the tit ...

for their assistance.

After port calls were concluded, the ships headed for Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

, where they found a conglomerate of warships from many different nations awaiting them "with decks manned and horns blaring": the battleships and with the cruiser and the Second Cruiser Squadron represented Great Britain's Royal Navy, battleships and with cruisers , and represented the Imperial Russian Navy

The Imperial Russian Navy () operated as the navy of the Russian Tsardom and later the Russian Empire from 1696 to 1917. Formally established in 1696, it lasted until dissolved in the wake of the February Revolution of 1917. It developed from ...

, and various gunboats represented France and the Netherlands. After coaling for five days, the ships got under way and left for home on 6 February 1909.

After weathering a few storms, the ships met nine of their fellow US Navy ships five days out of Hampton Roads: four battleships (''Maine'', , , and —the latter being the only sister of ''Connecticut'' to not make the cruise), two armored cruisers, and three scout cruisers. ''Connecticut'' then led all of these warships around Tail-of-the-Horseshoe Lightship on 22 February to pass in review of President Roosevelt, who was then on the presidential yacht anchored off Old Point Comfort

Old Point Comfort is a point of land located in the independent city of Hampton, Virginia. Previously known as Point Comfort, it lies at the extreme tip of the Virginia Peninsula at the mouth of Hampton Roads in the United States. It was renamed ...

, ending a trip. Roosevelt boarded the ship after she anchored and gave a short speech, saying, "You've done the trick. Other nations may do as you have done, but they'll follow you."

Pre-World War I

Following her return from the world cruise, ''Connecticut'' continued to serve as flagship of the Atlantic Fleet, interrupted only by a March 1909 overhaul at the New York Navy Yard. After rejoining the fleet, she cruised the East Coast from her base at Norfolk, Virginia. For the rest of 1909, the battleship conducted training and participated in ceremonial observances, such as the

Following her return from the world cruise, ''Connecticut'' continued to serve as flagship of the Atlantic Fleet, interrupted only by a March 1909 overhaul at the New York Navy Yard. After rejoining the fleet, she cruised the East Coast from her base at Norfolk, Virginia. For the rest of 1909, the battleship conducted training and participated in ceremonial observances, such as the Hudson–Fulton Celebration

The Hudson–Fulton Celebration from September 25 to October 9, 1909 in New York and New Jersey was an elaborate commemoration of the 300th anniversary of Henry Hudson’s discovery of the Hudson River and the 100th anniversary of Robert Fulton's ...

. In early January 1910, ''Connecticut'' left for Cuban waters and stayed there until late March when she returned to New York for a refit.Albertson (2007), p. 67 After several months conducting maneuvers and battle practice off the New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the Can ...

coast, she left for Europe on 2 November to go on a midshipman training cruise. She arrived in Portland

Portland most commonly refers to:

* Portland, Oregon, the largest city in the state of Oregon, in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States

* Portland, Maine, the largest city in the state of Maine, in the New England region of the northeas ...

, England on 15 November and was present during the 1 December birthday celebration of Queen Alexandra

Alexandra of Denmark (Alexandra Caroline Marie Charlotte Louise Julia; 1 December 1844 – 20 November 1925) was List of British royal consorts, Queen of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Empress of India, from 22 January 1901 t ...

, the queen mother

A queen mother is a former queen, often a queen dowager, who is the mother of the monarch, reigning monarch. The term has been used in English since the early 1560s. It arises in hereditary monarchy, hereditary monarchies in Europe and is also u ...

. ''Connecticut'' next visited Cherbourg, France, where she welcomed visitors from the town and also hosted commander-in-chief of the French Navy

The French Navy (french: Marine nationale, lit=National Navy), informally , is the maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the five military service branches of France. It is among the largest and most powerful naval forces in t ...

''Vice-Amiral'' Laurent Marin-Darbel, and a delegation of his officers. While there, a boat crew from ''Connecticut'' engaged a crew from the French battleship in a rowing race; ''Connecticut''s crew won by twelve lengths. ''Connecticut'' departed French waters for Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, on 30 December,Albertson (2007), p. 68 and stayed there until 17 March, when she departed for Hampton Roads.

''Connecticut'' was the leader of the ships that passed in review during the Presidential Fleet Review in New York, on 2 November; she then remained in New York, until 12 January 1912, when she returned to Guantánamo Bay. During a March overhaul at the Philadelphia Naval Yard

The Philadelphia Naval Shipyard was an important naval shipyard of the United States for almost two centuries.

Philadelphia's original navy yard, begun in 1776 on Front Street and Federal Street in what is now the Pennsport section of the ci ...

, the battleship relinquished her role as flagship to the armored cruiser . After the overhaul's completion, ''Connecticut''s activities through the end of 1912 included practicing with torpedoes in Fort Pond Bay

Fort Pond Bay is a bay off Long Island Sound at Montauk, New York that was site of the first port on the end of Long Island. The bay has a long naval and civilian history.

History

New-York Province and the American Revolution

Fort Pond Bay wa ...

, conducting fleet maneuvers, and battle practice off Block Island and the Virginia Capes.Albertson (2007), p. 69 Stopping in New York, ''Connecticut'' conducted training exercises in Guantánamo Bay from 13 February to 20 March; during this time (on the 28th), she once again became the Atlantic Fleet flagship for a brief and final time when she served in the interim as Rear Admiral Charles J. Badger transferred his flag from to . After taking on stores in Philadelphia, ''Connecticut'' sailed for Mexico and arrived on 22 April; she was to patrol the waters near Tampico

Tampico is a city and port in the southeastern part of the state of Tamaulipas, Mexico. It is located on the north bank of the Pánuco River, about inland from the Gulf of Mexico, and directly north of the state of Veracruz. Tampico is the fifth ...

and Vera Cruz, protecting American citizens and interests during disturbances there and in Haiti.Albertson (2007), p. 70

On 22 June 1912, ''Connecticut'' departed Mexican waters for Philadelphia, where she was dry docked for three months of repairs. Upon their completion, ''Connecticut'' conducted gunnery practice off the Virginia Capes. On 23 October, ''Connecticut'' became the flagship of the Fourth Battleship Division. After the division passed in review before Secretary of the Navy

On 22 June 1912, ''Connecticut'' departed Mexican waters for Philadelphia, where she was dry docked for three months of repairs. Upon their completion, ''Connecticut'' conducted gunnery practice off the Virginia Capes. On 23 October, ''Connecticut'' became the flagship of the Fourth Battleship Division. After the division passed in review before Secretary of the Navy George von Lengerke Meyer

George von Lengerke Meyer (June 24, 1858 – March 9, 1918) was a Massachusetts businessman and politician who served in the Massachusetts House of Representatives, as United States ambassador to Italy and Russia, as United States Postmaster Gener ...

on the 25th, ''Connecticut'' left for Genoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Italian region of Liguria and the sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of the 2011 Italian census, the Province of ...

, Italy, where she remained until 30 November. The battleship departed Italy for Vera Cruz and arrived on 23 December.Albertson (2007), p. 71 She took refugees from Mexico to Galveston and carried officers of the Army and representative from the Red Cross

The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement is a humanitarian movement with approximately 97 million volunteers, members and staff worldwide. It was founded to protect human life and health, to ensure respect for all human beings, and ...

back in the opposite direction.

On 29 May 1914, while still in Mexico, ''Connecticut'' relinquished the duty of flagship to , but remained in Mexico, until 2 July, when she left for Havana

Havana (; Spanish: ''La Habana'' ) is the capital and largest city of Cuba. The heart of the La Habana Province, Havana is the country's main port and commercial center.

. Arriving there on 8 July, ''Connecticut'' embarked Madison R. Smith, the US minister to Haiti, and took him to Port-au-Prince, arriving five days later. ''Connecticut'' remained in Haiti for a month, then left for Philadelphia on 8 August and arrived there on 14 August.

''Connecticut'' then went to Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and ...

and the Virginia Capes, for battle practice, after which she went into the Philadelphia Naval Yard for an overhaul. After more than 15 weeks, ''Connecticut'' emerged on 15 January 1915, and steamed south to Cuba, where she conducted training exercises. During maneuvers there in March 1915, a chain wrapped around her starboard propeller, breaking the shaft and forcing her return to Philadelphia, for repairs. She remained there until 31 July, when she embarked 433 men from the Second Regiment, First Brigade, of the United States Marine Corps for transport to Port-au-Prince, where they were put ashore on 5 August, as part of the US occupation of Haiti. ''Connecticut'' delivered supplies to amphibious troops in Cap-Haïtien

Cap-Haïtien (; ht, Kap Ayisyen; "Haitian Cape"), typically spelled Cape Haitien in English and often locally referred to as or , is a commune of about 190,000 people on the north coast of Haiti and capital of the department of Nord. Previousl ...

, on 5 September and remained near Haiti, for the next few months, supporting landing parties ashore, including detachments of Marines and sailors from ''Connecticut'' under the command of Major Smedley Butler

Major general (United States), Major General Smedley Darlington Butler (July 30, 1881June 21, 1940), nicknamed the "Maverick Marine", was a senior United States Marine Corps Officer (armed forces), officer who fought in the Philippine–American ...

. After departing Haiti, ''Connecticut'' arrived in Philadelphia, on 15 December, and was placed into the Atlantic Reserve Fleet

The United States Navy maintains a number of its ships as part of a reserve fleet, often called the "Mothball Fleet". While the details of the maintenance activity have changed several times, the basics are constant: keep the ships afloat and s ...

.Albertson (2007), p. 72

World War I

As part of the US response to Germany'sunrestricted submarine warfare

Unrestricted submarine warfare is a type of naval warfare in which submarines sink merchant ships such as freighters and tankers without warning, as opposed to attacks per prize rules (also known as "cruiser rules") that call for warships to s ...

, ''Connecticut'' was recommissioned on 3 October 1916. Two days later, Admiral Herbert O. Dunn made her the flagship of the Fifth Battleship Division, transferring his flag from ''Minnesota''.Albertson (2007), p. 73 ''Connecticut'' operated along the East Coast and in the Caribbean until the United States entered World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

on 6 April 1917. For the duration of the war, ''Connecticut'' was based in York River, Virginia. More than 1,000 trainees—midshipmen and gun crews for merchant ships—took part in exercises on her while she sailed in Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The Bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula (including the parts: the Eastern Shore of Maryland / ...

, and off the Virginia Capes.

Inter-war period

At the close of the war, ''Connecticut'' was assigned to the

At the close of the war, ''Connecticut'' was assigned to the Cruiser and Transport Force The Cruiser and Transport Service was a unit of the United States Navy's Atlantic Fleet during World War I that was responsible for transporting American men and materiel to France.

Composition

On 1 July 1918, the Cruiser and Transport Force was ...

for transport duty, and from 6 January – 22 June 1919, she made four voyages to return troops from France.Gleaves (1921), pp. 250–51Albertson (2007), p. 73–74 On 6 January, she left Hampton Roads, for Brest, France

Brest (; ) is a port city in the Finistère department, Brittany. Located in a sheltered bay not far from the western tip of the peninsula, and the western extremity of metropolitan France, Brest is an important harbour and the second French m ...

, where she embarked 1,000 troops. After bringing them to New York, arriving on 2 February, ''Connecticut'' traveled back to Brest, and picked up the 53rd Pioneer Regiment, a company of Marines, and a company of military police

Military police (MP) are law enforcement agencies connected with, or part of, the military of a state. In wartime operations, the military police may support the main fighting force with force protection, convoy security, screening, rear rec ...

, 1,240 troops in all. These men were delivered to Hampton Roads, on 24 March. After two months, ''Connecticut'' made another run overseas: following a short period of liberty in Paris, for her crew, she embarked 891 men variously from the 502nd Army Engineers, a medical detachment, and the Red Cross. They were dropped off in Newport News

Newport News () is an independent city in the U.S. state of Virginia. At the 2020 census, the population was 186,247. Located in the Hampton Roads region, it is the 5th most populous city in Virginia and 140th most populous city in the Uni ...

, on 22 June.Albertson (2007), p. 74 On 23 June 1919, after having returned over 4,800 men, ''Connecticut'' was reassigned as flagship of the Second Battleship Squadron of the Atlantic Fleet, under the command of Vice Admiral Hilary P. Jones

Hilary Pollard Jones, Jr. (14 November 1863 – 1 January 1938) was an officer in the United States Navy during the Spanish–American War and World War I. During the early 1920s, he served as Commander in Chief, United States Fleet.

Early life ...

.

While based in Philadelphia, for the next 11 months, ''Connecticut'' trained midshipmen. On 2 May 1920, 200 midshipmen boarded the ship for a training cruise. In company with the other battleships of her squadron, ''Connecticut'' sailed to the Caribbean, and through the Panama Canal, in order to visit four ports-of-call: Honolulu, Seattle, San Francisco, and San Pedro Bay (Los Angeles and Long Beach

Long Beach is a city in Los Angeles County, California. It is the 42nd-most populous city in the United States, with a population of 466,742 as of 2020. A charter city, Long Beach is the seventh-most populous city in California.

Incorporate ...

). After visiting all four, the squadron made their way back through the canal and headed for home. However, the port engine of ''Connecticut'' gave out three days after transiting the canal, requiring ''New Hampshire'' to tow the battleship into Guantánamo Bay. The pair arrived on 28 August. The midshipmen were debarked there,Albertson (2007), p. 75 and Vice Admiral Jones transferred his flag from ''Connecticut'' to his new flagship, . The Navy repair ship was dispatched from New York on 1 September to tow ''Connecticut'' to Philadelphia; they arrived at the Navy Yard there on 11 September.

On 21 March 1921, ''Connecticut'' again became the flagship of the Second Battleship Squadron when Rear Admiral Charles Frederick Hughes

Charles Frederick Hughes (14 October 1866 – 28 May 1934) was an admiral in the United States Navy who served as Chief of Naval Operations from 1927 to 1930.

Early life

Born in Bath, Maine, Hughes was appointed to the United States Naval A ...

took command. The ships of the squadron departed Philadelphia, on 7 April, to perform maneuvers and training exercises off Cuba, though they returned to take part in the Presidential Review in Hampton Roads, on 28 April. After participating in Naval Academy

A naval academy provides education for prospective naval officers.

See also

* Military academy

A military academy or service academy is an educational institution which prepares candidates for service in the officer corps. It normally pro ...

celebrations on Memorial Day

Memorial Day (originally known as Decoration Day) is a federal holiday in the United States for mourning the U.S. military personnel who have fought and died while serving in the United States armed forces. It is observed on the last Monda ...

, ''Connecticut'' and her squadmates departed on a midshipman cruise which took them to Europe. On 28 June, ''Connecticut'' hosted a Norwegian delegation that included King

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen, which title is also given to the consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contemporary indigenous peoples, the tit ...

Haakon VII

Haakon VII (; born Prince Carl of Denmark; 3 August 187221 September 1957) was the King of Norway from November 1905 until his death in September 1957.

Originally a Danish prince, he was born in Copenhagen as the son of the future Frederick ...

, Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister i ...

Otto Blehr

Otto Albert Blehr (17 February 1847 – 13 July 1927) was a Norwegian attorney and newspaper editor. He served as a politician representing the Liberal Party. He was the 8th prime minister of Norway from 1902 to 1903 during the Union between Swede ...

, the Minister of Defence, and the First Sea Lord of the Royal Norwegian Navy

The Royal Norwegian Navy ( no, Sjøforsvaret, , Sea defence) is the branch of the Norwegian Armed Forces responsible for naval operations of Norway. , the Royal Norwegian Navy consists of approximately 3,700 personnel (9,450 in mobilized state, ...

. After arriving in Portugal, on 21 July, the battleship hosted the Civil Governor of the Province of Lisbon and the Commander-in-Chief of the Portuguese Navy

The Portuguese Navy ( pt, Marinha Portuguesa, also known as ''Marinha de Guerra Portuguesa'' or as ''Armada Portuguesa'') is the naval branch of the Portuguese Armed Forces which, in cooperation and integrated with the other branches of the Port ...

. Six days later, ''Connecticut'' hosted the Portuguese president, António José de Almeida

António José de Almeida, GCTE, GCA, GCC, GCSE (; 27 July 1866 – 31 October 1929), was a Portuguese politician who served as the sixth president of Portugal from 1919 to 1923.

Early career

Born in Penacova to José António de Almeida ...

. The battleship squadron departed for Guantánamo Bay, on 29 July, and, after arrival there, remained for gunnery practice and exercises. ''Connecticut'', leaving the rest of the squadron, departed for Annapolis, and disembarked her midshipmen on 30 August, then proceeded to Philadelphia.Albertson (2007), p. 76

''Connecticut'' departed Philadelphia, for California, on 4 October, for duty with the Pacific Fleet. After touching at San Diego, on 27 October, she arrived on 28 October, at San Pedro, where Rear Admiral H.O. Stickney designated her the flagship of Pacific Fleet Training. For the next few months, ''Connecticut'' cruised along the West Coast, taking part in exercises and commemorations. Under the terms of the Washington Naval Treaty

The Washington Naval Treaty, also known as the Five-Power Treaty, was a treaty signed during 1922 among the major Allies of World War I, which agreed to prevent an arms race by limiting naval construction. It was negotiated at the Washington Nav ...

, which set tonnage limits for its signatory nations, the Navy designated ''Connecticut'' for scrapping

Scrap consists of recyclable materials, usually metals, left over from product manufacturing and consumption, such as parts of vehicles, building supplies, and surplus materials. Unlike waste, scrap has monetary value, especially recovered me ...

. Getting under way for her final voyage on 11 December, she made a five-day journey to the Puget Sound Navy Yard

Puget Sound Naval Shipyard, officially Puget Sound Naval Shipyard and Intermediate Maintenance Facility (PSNS & IMF), is a United States Navy shipyard covering 179 acres (0.7 km2) on Puget Sound at Bremerton, Washington in uninterrupted u ...

, where she was decommissioned on 1 March 1923. On 1 November 1923, the ex-''Connecticut'' was sold for scrap to Walter W. Johnson, of San Francisco, for $42,750.Albertson (2007), p. 77 In June 1924, the tug set a record for the largest tow by a single tug in history when she towed ''Connecticut'' from Seattle to Oakland, California, for scrapping.

Notes

References

Bibliography

* * * * *External links

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Connecticut (BB-18) Connecticut-class battleships Ships built in Brooklyn 1904 ships World War I battleships of the United States Military in Connecticut