The 1896 United States presidential election was the 28th quadrennial

presidential election

A presidential election is the election of any head of state whose official title is President.

Elections by country

Albania

The president of Albania is elected by the Assembly of Albania who are elected by the Albanian public.

Chile

The p ...

, held on Tuesday, November 3, 1896. Former

Governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until his assassination in 1901. As a politician he led a realignment that made his Republican Party largely dominant in t ...

, the

Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

candidate, defeated former

Representative William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator and politician. Beginning in 1896, he emerged as a dominant force in the History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, running ...

, the

Democratic candidate. The 1896 campaign, which took place during an economic depression known as the

Panic of 1893

The Panic of 1893 was an economic depression in the United States that began in 1893 and ended in 1897. It deeply affected every sector of the economy, and produced political upheaval that led to the political realignment of 1896 and the pres ...

, was a

political realignment

A political realignment, often called a critical election, critical realignment, or realigning election, in the academic fields of political science and political history, is a set of sharp changes in party ideology, issues, party leaders, regional ...

that ended the old

Third Party System

In the terminology of historians and political scientists, the Third Party System was a period in the history of political parties in the United States from the 1850s until the 1890s, which featured profound developments in issues of American n ...

and began the

Fourth Party System

The Fourth Party System is the term used in political science and history for the period in American political history from about 1896 to 1932 that was dominated by the Republican Party, except the 1912 split in which Democrats captured the White ...

.

Incumbent Democratic President

Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

did not seek election to a second consecutive term (which would have been his third overall), leaving the Democratic nomination open. Bryan, an attorney and former Congressman, galvanized support with his

Cross of Gold speech

The Cross of Gold speech was delivered by William Jennings Bryan, a former United States Representative from Nebraska, at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago on July 9, 1896. In his address, Bryan supported " free silver" (i.e. bim ...

, which called for a reform of the monetary system and attacked business leaders as the cause of ongoing economic depression. The

1896 Democratic National Convention

The 1896 Democratic National Convention, held at the Chicago Coliseum from July 7 to July 11, was the scene of William Jennings Bryan's nomination as the Democratic presidential candidate for the 1896 U.S. presidential election.

At age 36, B ...

repudiated the Cleveland administration and nominated Bryan on the fifth presidential ballot. Bryan then won the nomination of the

Populist Party, which had won several states in

1892

Events

January–March

* January 1 – Ellis Island begins accommodating immigrants to the United States.

* February 1 - The historic Enterprise Bar and Grill was established in Rico, Colorado.

* February 27 – Rudolf Diesel applies fo ...

and shared many of Bryan's policies. In opposition to Bryan, some conservative

Bourbon Democrat

Bourbon Democrat was a term used in the United States in the later 19th century (1872–1904) to refer to members of the Democratic Party who were ideologically aligned with fiscal conservatism or classical liberalism, especially those who su ...

s formed the

National Democratic Party and nominated Senator

John M. Palmer. McKinley prevailed by a wide margin on the first ballot of the

1896 Republican National Convention

The 1896 Republican National Convention was held in a temporary structure south of the St. Louis City Hall in Saint Louis, Missouri, from June 16 to June 18, 1896.

Former Governor William McKinley of Ohio was nominated for president on the firs ...

.

Since the onset of the Panic of 1893, the nation had been mired in a deep economic depression, marked by low prices, low profits, high unemployment, and violent strikes. Economic issues, especially

tariff

A tariff is a tax imposed by the government of a country or by a supranational union on imports or exports of goods. Besides being a source of revenue for the government, import duties can also be a form of regulation of foreign trade and p ...

policy and the question of whether the

gold standard

A gold standard is a monetary system in which the standard economic unit of account is based on a fixed quantity of gold. The gold standard was the basis for the international monetary system from the 1870s to the early 1920s, and from th ...

should be preserved for the

money supply

In macroeconomics, the money supply (or money stock) refers to the total volume of currency held by the public at a particular point in time. There are several ways to define "money", but standard measures usually include currency in circu ...

, were central issues. McKinley forged a conservative coalition in which businessmen, professionals, prosperous farmers, and skilled factory workers turned off by Bryan's

agrarian policies were heavily represented. McKinley was strongest in cities and in the

Northeast

The points of the compass are a set of horizontal, radially arrayed compass directions (or azimuths) used in navigation and cartography. A compass rose is primarily composed of four cardinal directions—north, east, south, and west—each sep ...

,

Upper Midwest

The Upper Midwest is a region in the northern portion of the U.S. Census Bureau's Midwestern United States. It is largely a sub-region of the Midwest. Although the exact boundaries are not uniformly agreed-upon, the region is defined as referring ...

, and

Pacific Coast

Pacific coast may be used to reference any coastline that borders the Pacific Ocean.

Geography Americas

Countries on the western side of the Americas have a Pacific coast as their western or southwestern border, except for Panama, where the Pac ...

. Republican campaign manager

Mark Hanna

Marcus Alonzo Hanna (September 24, 1837 – February 15, 1904) was an American businessman and Republican politician who served as a United States Senator from Ohio as well as chairman of the Republican National Committee. A friend and p ...

pioneered many modern campaign techniques, facilitated by a $3.5 million budget. Bryan presented his campaign as a crusade of the working man against the rich, who impoverished America by limiting the money supply. Silver, he said, was in ample supply and if coined into money would restore prosperity while undermining the illicit power of the money trust. Bryan was strongest in the

South

South is one of the cardinal directions or compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both east and west.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Proto-Germanic ''*sunþa ...

, rural

Midwest

The Midwestern United States, also referred to as the Midwest or the American Midwest, is one of four Census Bureau Region, census regions of the United States Census Bureau (also known as "Region 2"). It occupies the northern central part of ...

, and

Rocky Mountain states

The Mountain states (also known as the Mountain West or the Interior West) form one of the nine geographic divisions of the United States that are officially recognized by the United States Census Bureau. It is a subregion of the Western U ...

. Bryan's moralistic rhetoric and crusade for inflation (to be generated by the institution of

bimetallism

Bimetallism, also known as the bimetallic standard, is a monetary standard in which the value of the monetary unit is defined as equivalent to certain quantities of two metals, typically gold and silver, creating a fixed rate of exchange betw ...

) alienated conservatives.

Bryan campaigned vigorously throughout the

swing states

In American politics, the term swing state (also known as battleground state or purple state) refers to any state that could reasonably be won by either the Democratic or Republican candidate in a statewide election, most often referring to pres ...

of the Midwest, while McKinley conducted a

"front porch" campaign. At the end of an intensely heated contest, McKinley won a majority of the popular and

electoral vote. Bryan won 46.7% of the popular vote, while Palmer won just under 1% of the vote. Turnout was very high, passing 90% of the eligible voters in many places. The Democratic Party's repudiation of its Bourbon faction largely gave Bryan and his supporters control of the Democratic Party until the 1920s, and set the stage for Republican domination of the Fourth Party System.

Nominations

Republican Party nomination

Other candidates

At their

convention in

St. Louis, Missouri, held between June 16 and 18, 1896, the Republicans nominated

William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until his assassination in 1901. As a politician he led a realignment that made his Republican Party largely dominant in t ...

for president and

New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delawa ...

's

Garret Hobart

Garret Augustus Hobart (June 3, 1844 – November 21, 1899) was the 24th Vice President of the United States, serving from 1897 until his death in 1899. He was the sixth American vice president to die in office. Prior to serving as vice pre ...

for vice-president. McKinley had just vacated the office of

Governor of Ohio

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

. Both candidates were easily nominated on first ballots.

McKinley's campaign manager, a wealthy and talented Ohio businessman named

Mark Hanna

Marcus Alonzo Hanna (September 24, 1837 – February 15, 1904) was an American businessman and Republican politician who served as a United States Senator from Ohio as well as chairman of the Republican National Committee. A friend and p ...

, visited the leaders of large corporations and major, influential banks after the Republican Convention to raise funds for the campaign. Given that many businessmen and bankers were terrified of Bryan's populist rhetoric and demand for the end of the

gold standard

A gold standard is a monetary system in which the standard economic unit of account is based on a fixed quantity of gold. The gold standard was the basis for the international monetary system from the 1870s to the early 1920s, and from th ...

, Hanna had few problems in raising record amounts of money. As a result, Hanna raised a staggering $3.5 million for the campaign and outspent the Democrats by an estimated 5-to-1 margin. Major McKinley was the last veteran of the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

to be nominated for president by either major party.

Democratic Party nomination

Other candidates

One month after McKinley's nomination, supporters of silver-backed currency took control of the Democratic convention held in Chicago on July 7–11. Most of the Southern and Western delegates were committed to implementing the "free silver" ideas of the Populist Party. The convention repudiated President Cleveland's gold standard policies and then repudiated Cleveland himself. This, however, left the convention wide open: there was no obvious successor to Cleveland. A two-thirds vote was required for the nomination and the silverites had it in spite of the extreme regional polarization of the delegates. In a test vote on an anti-silver measure, the Eastern states (from Maryland to Maine), with 28% of the delegates, voted 96% in favor. The other delegates voted 91% against, so the silverites could count on a majority of 67% of the delegates.

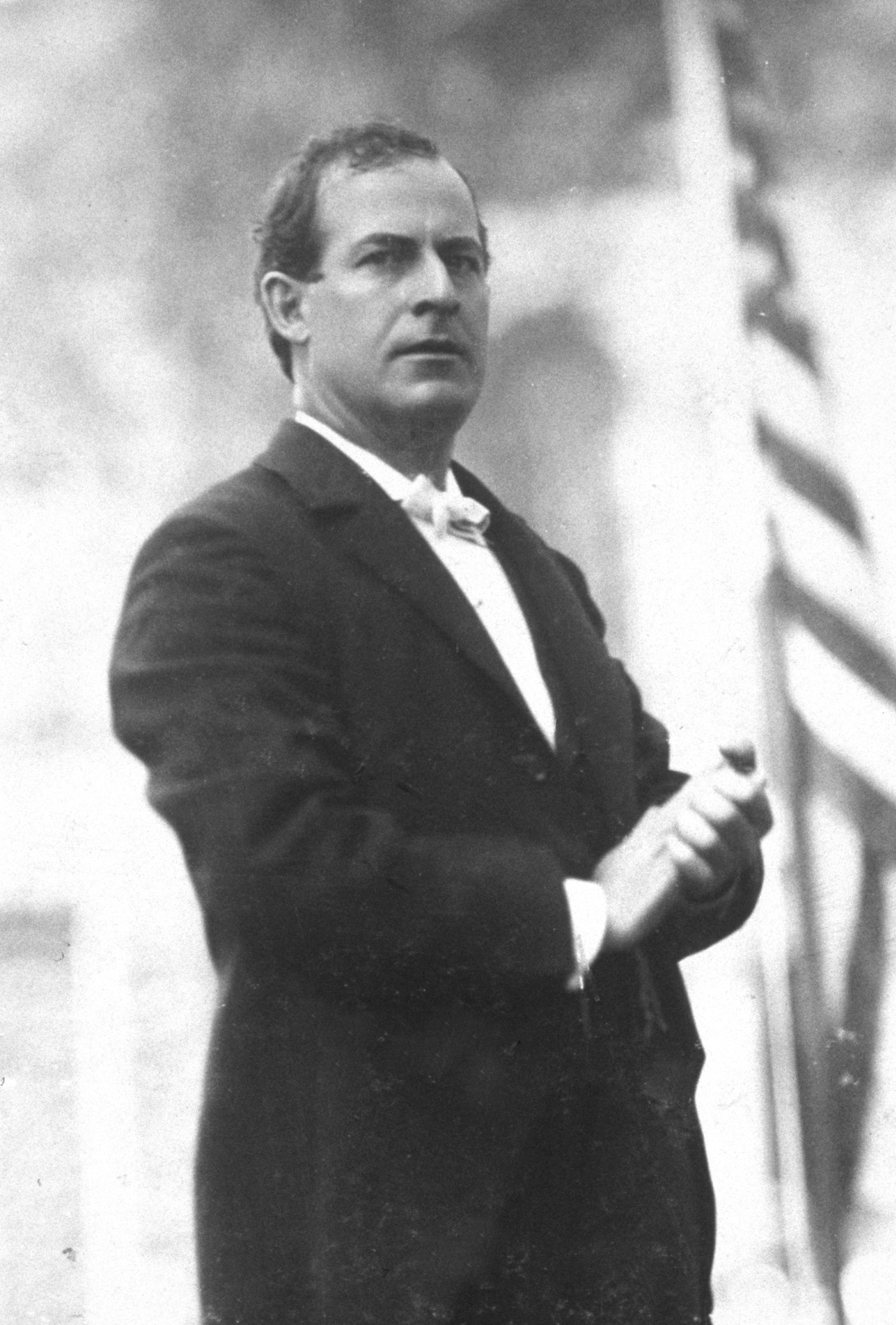

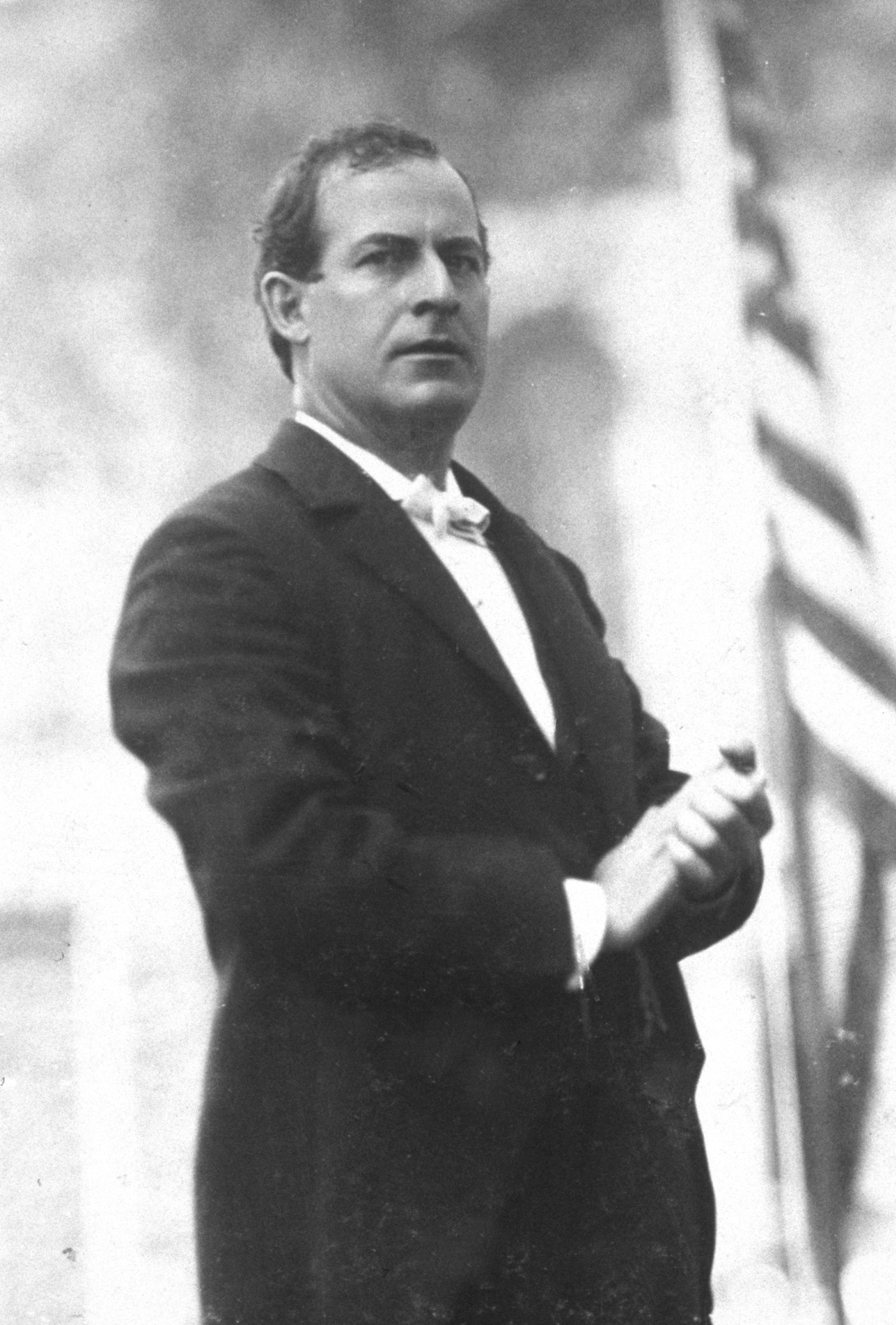

An attorney, former congressman, and unsuccessful Senate candidate named

William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator and politician. Beginning in 1896, he emerged as a dominant force in the History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, running ...

filled the void. A superb orator, Bryan hailed from Nebraska and spoke for the farmers who were suffering from the

economic depression

An economic depression is a period of carried long-term economical downturn that is result of lowered economic activity in one major or more national economies. Economic depression maybe related to one specific country were there is some economic ...

following the

Panic of 1893

The Panic of 1893 was an economic depression in the United States that began in 1893 and ended in 1897. It deeply affected every sector of the economy, and produced political upheaval that led to the political realignment of 1896 and the pres ...

. At the convention, Bryan delivered what has been considered one of the greatest political speeches in American history, the

"Cross of Gold" Speech. Bryan presented a passionate defense of farmers and factory workers struggling to survive the economic depression, and he attacked big-city business owners and leaders as the cause of much of their suffering. He called for reform of the monetary system, an end to the gold standard, and government relief efforts for farmers and others hurt by the economic depression. Bryan's speech was so dramatic that after he had finished many delegates carried him on their shoulders around the convention hall.

The following day, eight names were placed in nomination:

Richard "Silver Dick" Bland, William J. Bryan,

Claude Matthews

Claude Matthews (December 14, 1845 – August 28, 1898) was an American politician who served as the 23rd governor of the U.S. state of Indiana from 1893 to 1897. A farmer, he was nominated to prevent the loss of voters to the Populist Party ...

,

Horace Boies,

Joseph Blackburn,

John R. McLean,

Robert E. Pattison

Robert Emory Pattison (December 8, 1850August 1, 1904) was an American attorney and politician serving as the 19th Governor of Pennsylvania from 1883 to 1887 and 1891 to 1895. Pattison was the only Democratic Governor of Pennsylvania between ...

, and

Sylvester Pennoyer

Sylvester Pennoyer (July 6, 1831May 30, 1902) was an American educator, attorney, and politician in Oregon. He was born in Groton, New York, attended Harvard Law School, and moved to Oregon at age 25. A Democrat, he served two terms as the eigh ...

. Despite a strong initial showing by Bland, who led on the first three ballots, Bryan's electrifying speech helped him gain the momentum required to win the nomination, which he did on the fifth ballot after most of the other candidates withdrew in his favor.

Following Bland's defeat, his supporters attempted to nominate him as Bryan's running-mate; however, Bland was more interested in winning back his former seat in the House of Representatives, and so withdrew his name from consideration despite leading the early rounds of voting.

Arthur Sewall

Arthur Sewall (November 25, 1835 – September 5, 1900) was an American shipbuilder from Maine, best known as the Democratic nominee for Vice President of the United States in 1896, running mate to William Jennings Bryan. From 1888 to 1896 he ser ...

, a wealthy shipbuilder from Maine, was eventually chosen as the vice-presidential nominee. It was felt that Sewall's wealth might encourage him to help pay some campaign expenses. At just 36 years of age, Bryan was only a year older than the minimum age required by the Constitution to be president. Bryan remains the youngest person ever nominated by a major party for president.

Third parties and independents

Prohibition Party nomination

=Other candidates

=

The

Prohibition Party

The Prohibition Party (PRO) is a political party in the United States known for its historic opposition to the sale or consumption of alcoholic beverages and as an integral part of the temperance movement. It is the oldest existing third party ...

found itself going into the convention divided into two factions, each unwilling to give ground or compromise with the other. The "Broad-Gauge" wing, led by

Charles Bentley and former Kansas Governor

John St. John, demanded the inclusion of planks endorsing the free coinage of silver at 16:1 and of women's suffrage, the former refusing to accept the nomination if such amendments to the party platform were not approved. The "Narrow-Gauge" wing, which was led by Professor Samuel Dickie of Michigan and rallied around the candidacy of

Joshua Levering

Joshua Levering (September 12, 1845 - October 6, 1935) was a prominent Baptist and a candidate for president of the United States in 1896. He was president of the trustees of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Kentucky, p ...

, demanded that the party platform remain exclusively one dedicated to the prohibition of alcohol. It wasn't long into the convention when conflict between the two sides broke out over the nomination of a permanent chairman, with a number of presented candidates for the position withdrawing before Oliver Stewart of Illinois, a "Broad-Gauger", was nominated. A minority report made by St. John that supported the free coinage of silver, government control of railroads and telegraphs, an income tax and referendums was prevented from being tabled giving "Broad-Gaugers" confidence, but a number of those who voted in favor of the report were actually fence-sitters, undecided on how to vote, or were against gagging the report. After the report was brought forward by a majority of 188, "Narrow-Gaugers" campaigned among wavering delegates of the Northeast and Midwest in an effort to convince them of the electoral consequences that would come should the minority report be adopted, that Party gains in States like New York would reverse overnight in the face of free coinage and populism. When St. John's report was brought up to a formal vote the margins had largely reversed, with it being rejected 492 to 310. With the silver delegates still in shock and St. John attempting to move for a reconsideration, a move was made by Illinois "Narrow-Gaugers" to offer as a substitute to both the minority and majority reports a single plank platform centered around Prohibition. A rising vote was taken in lieu of a roll call, with the "Narrow-Gauge" Platform winning the vote and being adopted.

In an attempt to mollify

suffragists

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise, is the right to vote in public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in English, the right to v ...

who were incensed at the lack of a plank endorsing women's suffrage, the plank itself was adopted through a resolution by the convention by a near unanimous vote. By the time it came to the Party's nomination for president, many of the "Broad-Gaugers" were already openly considering bolting and running their own candidate as it became increasingly apparent that the "Narrow-Gaugers" had brought a majority of the convention under their influence, formal action was deferred until after the nomination for president was made. With Charles Bentley refusing to be nominating under the single-plank platform an attempt was made to nominate the recently retired Governor of the

Arizona Territory

The Territory of Arizona (also known as Arizona Territory) was a territory of the United States that existed from February 24, 1863, until February 14, 1912, when the remaining extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the state o ...

,

Louis Hughes, but as it became apparent that the "Narrow-Gauger" Joshua Levering was set to receive the support of most of the convention delegates, they opted to withdraw Hughes's name. Once Levering's nomination was confirmed without any visible opposition, around 200 of those who were suffragists, silverites or populists bolted the convention, led by Charles Bentley and John St. John, and would join with the National Reform "Party" to create the National Party. Afterwards the convention nominated with unanimity

Hale Johnson

Hale Johnson (August 21, 1847 – November 4, 1902) was an American attorney and politician who served as the Prohibition Party's vice presidential nominee in 1896 and ran for its presidential nomination in 1900.

Life

Hale Johnson was born on A ...

of Illinois for the Vice Presidency.

National Party nomination

Initially known as the "National Reform Party", the convention itself started only a day before the Prohibition National Convention, also being held in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Though initially only a gathering of eight or so delegates, it was hoped that any bolters from the Prohibition Party might find their way there and would support the nomination of Representative

Joseph C. Sibley for president. A sizable bolt did indeed occur upon the nomination of Joshua Levering by the Prohibition Party to the Presidency, with

Charles E. Bentley and former Kansas governor

John St. John leading a walkout of "Broad-Gaugers" from their convention, St. John himself exclaiming that the regular convention had been "...bought up by Wall Street." The two groups would reorganize as the "National Party" and swiftly nominated Charles Bentley for the presidency, with

James Southgate, the State Chairman for the North Carolina Prohibition Party, as his running mate. The delegates approved the minority report that had been rejected at the Prohibitionist Convention calling for free coinage and greenbacks, government control of railroads and telegraphs, direct election of senators and the president, and an income tax among others.

Socialist Labor Party nomination

The

Socialist Labor Convention was held in

New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

on July 9, 1896. The convention nominated

Charles Matchett

Charles Horatio Matchett (May 15, 1843 – October 24, 1919) was an American socialist politician. He is best remembered as the first candidate of the Socialist Labor Party of America for Vice President of the United States in the election of 1 ...

of New York and

Matthew Maguire of New Jersey. Its platform favored reduction in hours of labor; possession by the federal government of mines, railroads, canals, telegraphs, and telephones; possession by municipalities of water-works, gas-works, and electric plants; the issue of money by the federal government alone; the employment of the unemployed by the public authorities; abolition of the veto power; abolition of the United States Senate; women's suffrage; and uniform criminal law throughout the Union.

Peoples' Party nomination

=Other candidates

=

Of the several third parties active in 1896, by far the most prominent was the

People's Party. Formed in 1892, the Populists represented the philosophy of

agrarianism

Agrarianism is a political and social philosophy that has promoted subsistence agriculture, smallholdings, and egalitarianism, with agrarian political parties normally supporting the rights and sustainability of small farmers and poor peasants ag ...

(derived from

Jeffersonian democracy

Jeffersonian democracy, named after its advocate Thomas Jefferson, was one of two dominant political outlooks and movements in the United States from the 1790s to the 1820s. The Jeffersonians were deeply committed to American republicanism, whic ...

), which held that farming was a superior way of life that was being exploited by bankers and middlemen. The Populists attracted cotton farmers in the South and wheat farmers in the West, but significantly few farmers in the Northeast and rural Midwest. In the presidential election of 1892, Populist candidate

James B. Weaver

James Baird Weaver (June 12, 1833 – February 6, 1912) was a member of the United States House of Representatives and two-time candidate for President of the United States. Born in Ohio, he moved to Iowa as a boy when his family claimed ...

carried four states, and in 1894, the Populists scored victories in congressional and state legislature races in a number of Southern and Western states. In the Southern states, including Alabama, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Texas, the wins were obtained by

electoral fusion

Electoral fusion is an arrangement where two or more political parties on a ballot list the same candidate, pooling the votes for that candidate. It is distinct from the process of electoral alliances in that the political parties remain separa ...

with the Republicans against the dominant Bourbon Democrats, whereas in the rest of the country, fusion, if practiced, was typically undertaken with the Democrats, as in the state of Washington. By 1896, some Populists believed that they could replace the Democrats as the main opposition party to the Republicans. However, the Democrats' nomination of Bryan, who supported many Populist goals and ideas, placed the party in a dilemma. Torn between choosing their own presidential candidate or supporting Bryan, the party leadership decided that nominating their own candidate would simply divide the forces of reform and hand the election to the more conservative Republicans. At their national convention in 1896, the Populists chose Bryan as their presidential nominee. However, to demonstrate that they were still independent from the Democrats, the Populists also chose former Georgia Representative

Thomas E. Watson

Thomas Edward Watson (September 5, 1856 – September 26, 1922) was an American politician, attorney, newspaper editor and writer from Georgia. In the 1890s Watson championed poor farmers as a leader of the Populist Party, articulating an a ...

as their vice-presidential candidate instead of Arthur Sewall. Bryan eagerly accepted the Populist nomination, but was vague as to whether, if elected, he would choose Watson as his vice-president instead of Sewall. With this election, the Populists began to be absorbed into the Democratic Party; within a few elections the party would disappear completely. The 1896 election was particularly detrimental to the Populist Party in the South; the party divided itself between members who favored cooperation with the Democrats to achieve reform at the national level and members who favored cooperation with the Republicans to achieve reform at a state level.

Bryan's Democratic and Populist supporters organized joint "fusion" tickets in several states with pledged electors drawn from both parties. The ''New York Times'' counted seventy-one Populist and six Silver Republican electoral candidates pledged to Bryan. In ten states where the fusion ticket was successful, twenty-seven electors voted for Bryan for president and Watson for vice president. (The remainder of Bryan's 176 electors, including the Populist and Silver Republican electors from Colorado and Idaho, voted for Sewall.)

Silver Party nomination

The Silver Party was organized in 1892. Near the beginning of that year, U.S. senators from silver-producing states (Colorado, Idaho, Nevada, and Montana) began objecting to President

Benjamin Harrison's economic policies and advocated the free coinage of silver. Senator

Henry Teller

Henry Moore Teller (May 23, 1830February 23, 1914) was an American politician from Colorado, serving as a US senator between 1876–1882 and 1885–1909, also serving as Secretary of the Interior between 1882 and 1885. He strongly opposed the Da ...

notified the Senate that if the two major parties did not back down on their financial policies, the four western states would back a third party. The Portland Morning Oregonian reported on June 27, 1892, that a Silver Party was being organized along those lines.

Nevada silverites called a state convention to be held on June 5, 1892, just days following the close of the Democratic National Convention. The convention noted that neither the Republicans or Democrats addressed the silver concerns of western states and officially organized the "Silver Party of Nevada." Proceeding by itself, the Silver Party swept the state in 1892;

James Weaver, the

People's Party nominee for president running on the Silver ticket, won 66.8% of the vote.

Francis Newlands

Francis Griffith Newlands (August 28, 1846December 24, 1917) was a United States representative and Senator from Nevada and a member of the Democratic Party.

A supporter of westward expansion, he helped pass the Newlands Reclamation Act of 1 ...

was elected to the U.S. House with 72.5% of the vote. The Silverites took control of the legislature, assuring the election of

William Stewart to the U.S. Senate.

The success of the Nevada silverites spurred their brethren in Colorado to action; the Colorado Silver Party never materialized, however.

In the 1894 midterm elections, the Silver Party remained a Nevada party. It swept all statewide offices, formerly held by Republicans.

John Edward Jones was elected Governor with 50% of the vote; Newlands was re-elected with 44%.

Following the Democratic Party debacle in 1894, James Weaver began agitating for the creation of a nationwide Silver Party. He altered the People's Party platform from 1892 and eliminated planks he felt would be divisive for a larger party and began to lobby silver men around the nation. The first major statement by the national Silver Party was an address delivered to the American Bimetallic League, printed in the Emporia Daily Gazette on March 6, 1895. Letterhead for the nascent party promoted U.S. Representative

Joseph Sibley of Pennsylvania for president, noting that his endorsement by the Prohibitionists would secure that party's support.

Silver leaders met in Washington DC on January 22 to discuss holding a national convention. They decided to wait until after the conventions of the two major parties in case one of them agreed to the 16:1 coinage demands. Just a few days later, however, party regulars convinced the leaders to change course. On January 29, the leaders issued a call for a national convention to be held in St. Louis on July 22. J.J. Mott, the Silver Party National Chairman, went to great lengths to organize state parties, but his efforts did not produce dramatic results. The Silver State convention in Ohio was attended by just 20 people, even though the president of the Bimetallic League, A.J. Warner, lived there.

Although most Silverites had been pushing the nomination of Senator Teller, the situation changed with the Democratic nomination of William Jennings Bryan. Congressman Newlands was in Chicago as the official Silver Party visitor, and he announced on July 10 that the Silver Party should endorse the Democratic ticket. Chairman Mott, who was in St. Louis making final arrangements for the Silver National Convention, told a reporter five days later "All the Silver Party wants is silver, and the Democratic platform will give us that." I.B. Stevens, a member of the executive committee, told a reporter that the Silver Party "will bring to the support of

ryan

Ryan may refer to:

People and fictional characters

*Ryan (given name), a given name (including a list of people with the name)

* Ryan (surname), a surname (including a list of people with the name)

Places Australia

* Division of Ryan, an elect ...

hundreds of thousands who do not wish to vote a Democratic ticket."

On July 25, both Bryan and

Arthur Sewall

Arthur Sewall (November 25, 1835 – September 5, 1900) was an American shipbuilder from Maine, best known as the Democratic nominee for Vice President of the United States in 1896, running mate to William Jennings Bryan. From 1888 to 1896 he ser ...

would be nominated by acclamation.

National Democratic Party nomination

= Other candidates

=

The pro-gold Democrats reacted to Bryan's nomination with a mixture of anger, desperation, and confusion. A number of pro-gold Bourbon Democrats urged a "bolt" and the formation of a third party. In response, a hastily arranged assembly on July 24 organized the

National Democratic Party. A follow-up meeting in August scheduled a nominating convention for September in

Indianapolis

Indianapolis (), colloquially known as Indy, is the state capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Indiana and the seat of Marion County. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the consolidated population of Indianapolis and Marion ...

and issued an appeal to fellow Democrats. In this document, the National Democratic Party portrayed itself as the legitimate heir to Presidents

Jefferson,

Jackson

Jackson may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Jackson (name), including a list of people and fictional characters with the surname or given name

Places

Australia

* Jackson, Queensland, a town in the Maranoa Region

* Jackson North, Qu ...

, and Cleveland.

Delegates from forty-one states gathered at the National Democratic Party's national nominating convention in Indianapolis on September 2. Some delegates planned to nominate Cleveland, but they relented after a telegram arrived stating that he would not accept. Senator

William Freeman Vilas

William Freeman Vilas (July 9, 1840August 27, 1908) was an American lawyer, politician, and United States Senator. In the U.S. Senate, he represented the state of Wisconsin for one term, from 1891 to 1897. As a prominent Bourbon Democrat, he ...

from Wisconsin, the main drafter of the National Democratic Party's platform, was a favorite of the delegates. However, Vilas refused to run as the party's sacrificial lamb. The choice instead was

John M. Palmer, a 79-year-old former senator from Illinois.

Simon Bolivar Buckner

Simon Bolivar Buckner ( ; April 1, 1823 – January 8, 1914) was an American soldier, Confederate combatant, and politician. He fought in the United States Army in the Mexican–American War. He later fought in the Confederate States Army ...

, a 73-year-old former governor of Kentucky, was nominated by acclamation for vice-president. The ticket, symbolic of post-Civil War reconciliation, featured the oldest combined age of the candidates in American history.

Despite their advanced ages, Palmer and Buckner embarked on a busy speaking tour, including visits to most major cities in the East. This won them considerable respect from the party faithful, although some found it hard to take the geriatric campaigning seriously. "You would laugh yourself sick could you see old Palmer," wrote lawyer

Kenesaw Mountain Landis

Kenesaw Mountain Landis (; November 20, 1866 – November 25, 1944) was an American jurist who served as a United States federal judge from 1905 to 1922 and the first Commissioner of Baseball from 1920 until his death. He is remembered for his ...

. "He has actually gotten it into his head he is running for office." The Palmer ticket was considered to be a vehicle to elect McKinley for some Gold Democrats, such as

William Collins Whitney

William Collins Whitney (July 5, 1841February 2, 1904) was an American political leader and financier and a prominent descendant of the John Whitney family. He served as Secretary of the Navy in the first administration of President Grover Cl ...

and

Abram Hewitt

Abram Stevens Hewitt (July 31, 1822January 18, 1903) was an American politician, educator, ironmaking industrialist, and lawyer who was mayor of New York City for two years from 1887–1888. He also twice served as a U.S. Congressman from a ...

, the treasurer of the National Democratic Party, and they received quiet financial support from Mark Hanna. Palmer himself said at a campaign stop that if "this vast crowd casts its vote for William McKinley next Tuesday, I shall charge them with no sin." There was even some cooperation with the Republican Party, especially in finances. The Republicans hoped that Palmer could draw enough Democratic votes from Bryan to tip marginal Midwestern and border states into McKinley's column. In a private letter, Hewitt underscored the "entire harmony of action" between both parties in standing against Bryan.

However, the National Democratic Party was not merely an adjunct to the McKinley campaign. An important goal was to nurture a loyal remnant for future victory. Repeatedly they depicted Bryan's prospective defeat, and a credible showing for Palmer, as paving the way for ultimate recapture of the Democratic Party, and this did indeed happen in 1904.

Campaign strategies

While the Republican Party entered 1896 assuming that the Democrats were in shambles and victory would be easy, especially after the unprecedented Republican landslide in the congressional elections of 1894, the nationwide emotional response to the Bryan candidacy changed everything. By summer, it appeared that Bryan was ahead in the South and West and probably also in the Midwest. An entirely new strategy was called for by the McKinley campaign. It was designed to educate voters in the money issues, to demonstrate silverite fallacies, and to portray Bryan himself as a dangerous crusader. McKinley would be portrayed as the safe and sound champion of jobs and sound money, with his high tariff proposals guaranteed to return prosperity for everyone. The McKinley campaign would be national and centralized, using the Republican National Committee as the tool of the candidate, instead of the state parties' tool. Furthermore, the McKinley campaign stressed his pluralistic commitment to prosperity for all groups (including minorities).

Financing

The McKinley campaign invented a new form of campaign financing that has dominated American politics ever since. Instead of asking office holders to return a cut of their pay, Hanna went to financiers and industrialists and made a business proposition. He explained that Bryan would win if nothing happened, and that the McKinley team had a winning counterattack that would be very expensive. He then would ask them how much it was worth to the business not to have Bryan as president. He suggested an amount and was happy to take a check. Hanna had moved beyond partisanship and campaign rhetoric to a businessman's thinking about how to achieve a desired result. He raised $3.5 million. Hanna brought in banker

Charles G. Dawes

Charles Gates Dawes (August 27, 1865 – April 23, 1951) was an American banker, general, diplomat, composer, and Republican politician who was the 30th vice president of the United States from 1925 to 1929 under Calvin Coolidge. He was a co-rec ...

to run his Chicago office and spend about $2 million in the critical region.

Meanwhile, traditional funders of the Democratic Party (mostly financiers from the Northeast) rejected Bryan, although he did manage to raise about $500,000. Some of it came from businessmen with interests in silver mining.

The financial disparity grew larger and larger as the Republicans funded more and more rallies, speeches, and torchlight parades, as well as hundreds of millions of pamphlets attacking Bryan and praising McKinley. Lacking a systematic fund-raising system, Bryan was unable to tap his potential supporters, and he had to rely on passing the hat at rallies. National Chairman Jones pleaded, "No matter in how small sums, no matter by what humble contributions, let the friends of liberty and national honor contribute all they can."

Republican attacks on Bryan

Increasingly, the Republicans personalized their attacks on Bryan as a dangerous religious fanatic. The counter-crusading rhetoric focused on Bryan as a reckless revolutionary whose policies would destroy the economic system. Illinois Governor

John Peter Altgeld

John Peter Altgeld (December 30, 1847 – March 12, 1902) was an American politician and the 20th Governor of Illinois, serving from 1893 until 1897. He was the first Democrat to govern that state since the 1850s. A leading figure of the Pro ...

was running for re-election after having pardoned several of the anarchists convicted in the

Haymarket affair

The Haymarket affair, also known as the Haymarket massacre, the Haymarket riot, the Haymarket Square riot, or the Haymarket Incident, was the aftermath of a bombing that took place at a labor demonstration on May 4, 1886, at Haymarket Square i ...

. Republican posters and speeches linked Altgeld and Bryan as two dangerous anarchists. The Republican Party tried any number of tactics to ridicule Bryan's economic policies. In one case they printed fake dollar bills which had Bryan's face and read "IN GOD WE TRUST ... FOR THE OTHER 53 CENTS", illustrating their claim that a dollar bill would be worth only 47 cents if it was backed by silver instead of gold.

Ethnic responses

The Democratic Party in Eastern and Midwestern cities had a strong German Catholic base that was alienated by free silver and inflationist panaceas. They showed little enthusiasm for Bryan, although many were worried that a Republican victory would bring prohibition into play. The Irish Catholics disliked Bryan's revivalistic rhetoric and worried about prohibition as well. However their leaders decided to stick with Bryan, since the departure of so many Bourbon businessmen from the party left the Irish increasingly in control.

Labor unions and skilled workers

The Bryan campaign appealed first of all to farmers. It told urban workers that their return to prosperity was possible only if the farmers prospered first. Bryan made the point bluntly in the "Cross of Gold" speech, delivered in Chicago just 25 years after that city had indeed burned down: "Burn down your cities and leave our farms, and your cities will spring up again; but destroy our farms, and the grass will grow in the streets of every city in the country." Juxtaposing "our farms" and "your cities" did not go over well in cities; they voted 59% for McKinley. Among the industrial cities, Bryan carried only two (

Troy, New York

Troy is a City (New York), city in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York and the county seat of Rensselaer County, New York, Rensselaer County. The city is located on the western edge of Rensselaer County and on the eastern bank of the Huds ...

, and

Fort Wayne, Indiana

Fort Wayne is a city in and the county seat of Allen County, Indiana, United States. Located in northeastern Indiana, the city is west of the Ohio border and south of the Michigan border. The city's population was 263,886 as of the 2020 Censu ...

).

The main labor unions were reluctant to endorse Bryan because their members feared inflation. Railroad workers especially worried that Bryan's silver programs would bankrupt the railroads, which were in a shaky financial condition in the depression and whose bonds were payable in gold. Factory workers saw no advantage in inflation to help miners and farmers, because their urban cost of living would shoot up and they would be hurt. The McKinley campaign gave special attention to skilled workers, especially in the Midwest and adjacent states. Secret polls show that large majorities of railroad and factory workers voted for McKinley.

The fall campaign

Throughout the campaign the South and Mountain states appeared certain to vote for Bryan, whereas the East was certain for McKinley. In play were the Midwest and the Border States.

The Republican Party amassed an unprecedented war chest at all levels: national, state and local. Outspent and shut out of the party's traditional newspapers, Bryan decided his best chance to win the election was to conduct a vigorous national speaking tour by train. His fiery crusading rhetoric to huge audiences would make his campaign a newsworthy story that the hostile press would have to cover, and he could speak to the voters directly instead of through editorials. He was the first presidential candidate since Stephen Douglas in 1860 to canvass directly, and the first ever to criss-cross the nation and meet voters in person.

The novelty of seeing a visiting presidential candidate, combined with Bryan's spellbinding oratory and the passion of his believers, generated huge crowds. Silverites welcomed their hero with all-day celebrations of parades, band music, picnic meals, endless speeches, and undying demonstrations of support. Bryan focused his efforts on the Midwest, which everyone agreed would be the decisive battleground in the election. In just 100 days, Bryan gave over 500 speeches to several million people. His record was 36 speeches in one day in St. Louis. Relying on just a few hours of sleep a night, he traveled 18,000 miles by rail to address five million people, often in a hoarse voice; he would explain that he left his real voice at the previous stops where it was still rallying the people.

In contrast to Bryan's dramatic efforts, McKinley conducted a "front porch" campaign from his home in

Canton, Ohio

Canton () is a city in and the county seat of Stark County, Ohio. It is located approximately south of Cleveland and south of Akron in Northeast Ohio. The city lies on the edge of Ohio's extensive Amish country, particularly in Holmes an ...

.

Instead of having McKinley travel to see the voters, Mark Hanna brought 500,000 voters by train to McKinley's home. Once there, McKinley would greet the men from his porch. His well-organized staff prepared both the remarks of the visiting delegations and the candidate's responses, focusing the comments on the assigned topic of the day. The remarks were issued to the newsmen and telegraphed nationwide to appear in the next day's papers. Bryan, with practically no staff, gave much the same talk over and over again. McKinley labeled Bryan's proposed social and economic reforms as a serious threat to the national economy. With the depression following the Panic of 1893 coming to an end, support for McKinley's more conservative economic policies increased, while Bryan's more radical policies began to lose support among Midwestern farmers and factory workers.

To ensure victory, Hanna paid large numbers of Republican orators (including

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

) to travel around the nation denouncing Bryan as a dangerous radical. There were also reports that some potentially Democratic voters were intimidated into voting for McKinley. For example, some factory owners posted signs the day before the election announcing that, if Bryan won the election, the factory would be closed and the workers would lose their jobs.

Bryan's midsummer surge in the Midwest played out as the intense Republican counter-crusade proved effective. Bryan spent most of October in the Midwest, making 160 of his final 250 speeches there. Morgan noted, "full organization, Republican party harmony, a campaign of education with the printed and spoken word would more than counteract" Bryan's speechmaking.

Several of Bryan's advisors recommended additional campaigning in the Upper South States of Kentucky, West Virginia, Maryland and Delaware. Another plan called for a coastal tour from Washington State to Southern California. Bryan however, opted to concentrate in the Mid-West and to launch a unity tour into the heavily Republican Northeast. Bryan saw no chance of winning in New England, but felt that he needed to make a truly national appeal. On election day the results from the Pacific Coast and Upper South would be the closest of the election.

Results

McKinley secured a solid victory in the

electoral college by carrying the core of the East and Northeast, while Bryan did well among the farmers of the South, West, and rural Midwest. The large German-American voting bloc supported McKinley, who gained large majorities among the middle class, skilled factory workers, railroad workers, and large-scale farmers.

The national popular vote was rather close, as McKinley defeated Bryan by 602,500 votes, receiving 51% to Bryan's 46.7%: a shift of 53,000 votes in California, Kentucky, Ohio and Oregon would have won Bryan the election despite McKinley winning the majority of the popular vote, but due to the joint Democratic-Populist ticket, this also would have left Hobart and Sewell short of the 224 electoral votes required to win the vice-presidency, forcing a contingent election for vice-president in the

Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

.

The National Democrats did not carry any states, but they did divide the Democratic vote in some states and helped the Republicans flip Kentucky; Gold Democrats made much of the fact that Palmer's small vote in Kentucky was higher than McKinley's very narrow margin in that state. This was the first time a Republican presidential candidate had ever carried Kentucky, but they did not do so again until

Calvin Coolidge

Calvin Coolidge (born John Calvin Coolidge Jr.; ; July 4, 1872January 5, 1933) was the 30th president of the United States from 1923 to 1929. Born in Vermont, Coolidge was a Republican lawyer from New England who climbed up the ladder of Ma ...

in 1924. From this, they concluded that Palmer had siphoned off needed Democratic votes and hence thrown the state to McKinley. However, McKinley would have won the overall election even if he had lost Kentucky to Bryan.

Mayor

Tom L. Johnson

Tom Loftin Johnson (July 18, 1854 – April 10, 1911) was an American industrialist, Georgist politician, and important figure of the Progressive Era and a pioneer in urban political and social reform. He was a U.S. Representative from 1891 to ...

of

Cleveland, Ohio

Cleveland ( ), officially the City of Cleveland, is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County. Located in the northeastern part of the state, it is situated along the southern shore of Lake Erie, across the U.S ...

, summed up the campaign as the "first great protest of the American people against monopoly – the first great struggle of the masses in our country against the privileged classes."

According to a 2017

National Bureau of Economic Research

The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) is an American private nonprofit research organization "committed to undertaking and disseminating unbiased economic research among public policymakers, business professionals, and the academic c ...

paper, "Bryan did well where mortgage interest rates were high, railroad penetration was low, and crop prices had declined by most over the previous decade. Using our estimates, we show that further declines in crop prices or increases in interest rates would have been enough to tip the Electoral College in Bryan's favor. But to change the outcome, the additional fall in crop prices would have had to be large."

A 2022 study found that campaign visits by Bryan increased his vote share by one percentage point on average.

General results

McKinley received a little more than seven million votes, Bryan a little less than six and a half million, about 800,000 in excess of the Democratic vote in

1892

Events

January–March

* January 1 – Ellis Island begins accommodating immigrants to the United States.

* February 1 - The historic Enterprise Bar and Grill was established in Rico, Colorado.

* February 27 – Rudolf Diesel applies fo ...

. It was larger than the Democratic Party was to poll in

1900

As of March 1 ( O.S. February 17), when the Julian calendar acknowledged a leap day and the Gregorian calendar did not, the Julian calendar fell one day further behind, bringing the difference to 13 days until February 28 ( O.S. February 15), 2 ...

,

1904

Events

January

* January 7 – The distress signal ''CQD'' is established, only to be replaced 2 years later by ''SOS''.

* January 8 – The Blackstone Library is dedicated, marking the beginning of the Chicago Public Library syst ...

, or

1912

Events January

* January 1 – The Republic of China is established.

* January 5 – The Prague Conference (6th All-Russian Conference of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party) opens.

* January 6

** German geophysicist Alfred ...

. It was somewhat less, however, than the combined vote for the Democratic and Populist nominees had been in 1892. In contrast, McKinley received nearly 2,000,000 more votes than had been cast for

Benjamin Harrison

Benjamin Harrison (August 20, 1833March 13, 1901) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 23rd president of the United States from 1889 to 1893. He was a member of the Harrison family of Virginia–a grandson of the ninth pr ...

, the Republican nominee, in 1892. The Republican vote was to be but slightly increased during the next decade.

Realignment of 1896

The 1896 presidential election is often seen as a

realigning election

A political realignment, often called a critical election, critical realignment, or realigning election, in the academic fields of political science and political history, is a set of sharp changes in party ideology, issues, party leaders, regiona ...

, in which McKinley's view of a stronger central government building American industry through protective tariffs and a dollar based on gold triumphed. The new

Fourth Party System

The Fourth Party System is the term used in political science and history for the period in American political history from about 1896 to 1932 that was dominated by the Republican Party, except the 1912 split in which Democrats captured the White ...

then displaced the near-deadlock in the

Third Party System

In the terminology of historians and political scientists, the Third Party System was a period in the history of political parties in the United States from the 1850s until the 1890s, which featured profound developments in issues of American n ...

since the Civil War. The Republicans now usually dominated in the major states and nationwide down to

the 1932 election, another realigning election with the ascent of

Franklin Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

and the

Fifth Party System

The Fifth Party System is the era of American national politics that began with the New Deal in 1932 under President Franklin D. Roosevelt. This era of Democratic Party-dominance emerged from the realignment of the voting blocs and interest gro ...

. Phillips argues that McKinley was the only Republican who could have defeated Bryan—he concludes that Eastern candidates would have done badly against the Illinois-born Bryan in the crucial Midwest. Although Bryan was popular among rural voters, "McKinley appealed to a very different industrialized, urbanized America."

Geography of results

One-half of the total vote of the nation was polled in eight states carried by McKinley (New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin). In these states, Bryan not only ran far behind the Republican candidate, but also polled considerably less than half of his total vote.

[''The Presidential Vote, 1896–1932'', Edgar E. Robinson, p. 4]

Bryan only won in twelve of the eighty-two cites in the United States with populations above 45,000 with seven of those being in the

Solid South

The Solid South or Southern bloc was the electoral voting bloc of the states of the Southern United States for issues that were regarded as particularly important to the interests of Democrats in those states. The Southern bloc existed especial ...

. In the states that Bryan won seven of the seventeen cities voted McKinley while in the states that voted for McKinley only three of the sixty-five cities voted for Bryan. Bryan lost in every county in New England and only won one county in

New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

, with Bryan even losing in traditionally Democratic

New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

.

In only one other section, in the six states of

New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

, was the Republican lead great; the Republican vote (614,972) was more than twice the Democratic vote (242,938), and every county was carried by the Republicans.

The

West North Central section gave a slight lead to McKinley, as did the

Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the contine ...

section. Nevertheless, within these sections, the states of Missouri, South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas, and Washington were carried by Bryan.

In the

South Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the "Old World" of Africa, Europe a ...

section and in the

East South Central section, the Democratic lead was pronounced, and in the

West South Central section and in the

Mountain

A mountain is an elevated portion of the Earth's crust, generally with steep sides that show significant exposed bedrock. Although definitions vary, a mountain may differ from a plateau in having a limited summit area, and is usually higher ...

section, the vote for Bryan was overwhelming. In these four sections, comprising 21 states, McKinley carried only 322 counties and four states – Delaware, Maryland, West Virginia, and Kentucky.

A striking feature of this examination of the state returns is found in the overwhelming lead for one or the other party in 22 of the 45 states. It was true of the McKinley vote in every New England state and in New York, Pennsylvania, and Illinois. It was also true of the Bryan vote in eight states of the lower South and five states of the Mountain West. Sectionalism was thus marked in this first election of the

Fourth Party System

The Fourth Party System is the term used in political science and history for the period in American political history from about 1896 to 1932 that was dominated by the Republican Party, except the 1912 split in which Democrats captured the White ...

.

Records

This was the last election in which the Democrats won South Dakota until 1932, the last in which the Democrats won Utah and Washington until 1916, and the last in which the Democrats won Kansas and Wyoming until 1912. It was also the last time that South Dakota and Washington voted against the Republicans until they voted for the Progressive Party in 1912. This also constitutes the only election since their statehoods when a Republican won the presidency without winning Kansas, South Dakota, Utah, or Wyoming. Today these are solidly Republican states and have not backed a Democratic nominee since

Lyndon Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

's 1964 landslide over

Barry Goldwater

Barry Morris Goldwater (January 2, 1909 – May 29, 1998) was an American politician and United States Air Force officer who was a five-term U.S. Senator from Arizona (1953–1965, 1969–1987) and the Republican Party nominee for president ...

.

Southern votes

In the South, there were numerous Republican counties, notably in Texas, Tennessee, North Carolina, Kentucky, northern Alabama and Virginia, representing a mix of white

Southern Unionist

In the United States, Southern Unionists were white Southerners living in the Confederate States of America opposed to secession. Many fought for the Union during the Civil War. These people are also referred to as Southern Loyalists, Union Lo ...

counties along with majority black counties in areas where black disenfranchisement was not yet complete (such as North Carolina, where a Republican-Populist fusion ticket had captured the General Assembly in 1894). Even in Georgia, a state in the

Deep South

The Deep South or the Lower South is a cultural and geographic subregion in the Southern United States. The term was first used to describe the states most dependent on plantations and slavery prior to the American Civil War. Following the wa ...

, there were counties returning Republican majorities.

(a) ''Includes 912,241 votes as the People's nominee''

(b) ''Sewall was Bryan's Democratic running mate.''

(c) ''Watson was Bryan's People's running mate.''

Source (Popular Vote):

Source (Electoral Vote):

Geography of results

Image:1896 United States presidential election results map by county.svg, Results by county, shaded according to winning candidate's percentage of the vote

Cartographic gallery

Image:PresidentialCounty1896Colorbrewer.gif, Map of presidential election results by county

Image:RepublicanPresidentialCounty1896Colorbrewer.gif, Map of Republican presidential election results by county

Image:DemocraticPresidentialCounty1896Colorbrewer.gif, Map of Democratic presidential election results by county

Image:OtherPresidentialCounty1896Colorbrewer.gif, Map of "other" presidential election results by county

Image:CartogramPresidentialCounty1896Colorbrewer.gif, Cartogram

A cartogram (also called a value-area map or an anamorphic map, the latter common among German-speakers) is a thematic map of a set of features (countries, provinces, etc.), in which their geographic size is altered to be directly proportiona ...

of presidential election results by county

Image:CartogramRepublicanPresidentialCounty1896Colorbrewer.gif, Cartogram of Republican presidential election results by county

Image:CartogramDemocraticPresidentialCounty1896Colorbrewer.gif, Cartogram of Democratic presidential election results by county

Image:CartogramOtherPresidentialCounty1896Colorbrewer.gif, Cartogram of "other" presidential election results by county

Results by state

Close states

Margin of victory less than 1% (26 electoral votes; 20 won by Republicans; 6 by Democrats):

#

Kentucky, 0.06% (277 votes)

#

South Dakota, 0.22% (183 votes)

#

California, 0.64% (1,922 votes)

Margin of victory less than 5% (55 electoral votes; 42 won by Republicans; 13 by Democrats):

#

Oregon, 2.09% (2,040 votes)

#

Indiana, 2.85% (18,181 votes)

#

Kansas, 3.69% (12,330 votes)

#

Wyoming, 3.74% (789 votes)

#

Ohio, 4.78% (48,494 votes) (tipping point state)

Margin of victory between 5% and 10% (66 electoral votes; 6 won by Republicans; 60 by Democrats):

#

Nebraska, 5.35% (11,943 votes)

#

West Virginia, 5.40% (10,899 votes)

#

Tennessee, 5.76% (18,485 votes)

#

North Carolina, 5.82% (19,286 votes)

#

Virginia, 6.56% (19,329 votes)

#

Missouri, 8.71% (58,727 votes)

Statistics

Counties with Highest Percent of Vote (Republican)

#

Zapata County, Texas

Zapata County is a county located in the U.S. state of Texas. As of the 2020 census, its population was 13,889. Its county seat is Zapata. The county is named for Colonel José Antonio de Zapata, a rancher in the area who rebelled against Me ...

94.34%

#

Leslie County, Kentucky 91.39%

#

Addison County, Vermont

Addison County is a county located in the U.S. state of Vermont. As of the 2020 census, the population was 37,363. Its shire town ( county seat) is the town of Middlebury.

History

Iroquois settled in the county before Europeans arrived in ...

89.17%

#

Unicoi County, Tennessee

Unicoi County () is a county located in the U.S. state of Tennessee. As of the 2010 census, the population was 18,313. Its county seat is Erwin. ''Unicoi'' is a Cherokee word meaning "white," "hazy," "fog-like," or "fog draped," and refers to ...

89.04%

#

Keweenaw County, Michigan

Keweenaw County (, ; , ) is a county in the Upper Peninsula of the U.S. state of Michigan, the state's northernmost county. As of the 2020 United States Census, the population was 2,046, making it Michigan's least populous county. It is also the ...

88.96%

Counties with Highest Percent of Vote (Democratic)

#

West Carroll Parish, Louisiana

West Carroll Parish (french: link=no, Paroisse de Carroll Ouest) is a parish located in the northeastern part of the U.S. state of Louisiana. As of the 2020 census, the population was 9,751. The parish seat is Oak Grove. The parish was fo ...

99.84%

#

Leflore County, Mississippi

Leflore County is a county located in the U.S. state of Mississippi. As of the 2010 census, the population was 32,317. The county seat is Greenwood. The county is named for Choctaw leader Greenwood LeFlore, who signed a treaty to cede his p ...

99.68%

#

Smith County, Mississippi

Smith County is a county located in the U.S. state of Mississippi. As of the 2010 census, the population was 16,491. Its county seat is Raleigh. Smith County is a prohibition or dry county.

History

Smith County is named for Major David Smi ...

99.26%

#

Pitkin County, Colorado

Pitkin County is a county in the U.S. state of Colorado. As of the 2020 census, the population was 17,358. The county seat and largest city is Aspen. The county is named for Colorado Governor Frederick Walker Pitkin. Pitkin County has the sev ...

99.21%

#

Neshoba County, Mississippi

Neshoba County is located in the central part of the U.S. state of Mississippi. As of the 2020 census, the population was 29,087. Its county seat is Philadelphia. It was named after ''Nashoba'', a Choctaw chief. His name means " wolf" in t ...

99.15%

Counties with Highest Percent of Vote (Populist)

#

Madera County, California

Madera County (), officially the County of Madera, is a county at the geographic center of the U.S. state of California. As of the 2020 census, the population was 156,255. The county seat is Madera.

Madera County comprises the Madera, CA M ...

62.80%

#

Lake County, California

Lake County is a county located in the north central portion of the U.S. state of California. As of the 2020 census, the population was 68,163. The county seat is Lakeport. The county takes its name from Clear Lake, the dominant geographic f ...

61.95%

#

Stanislaus County, California

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Images, from top down, left to right: Modesto Arch, Knights Ferry's General Store, a view of the Tuolumne River from Waterford

, image_flag =

, ...

59.00%

#

San Benito County, California

San Benito County (; ''San Benito'', Spanish for " St. Benedict"), officially the County of San Benito, is a county located in the Coast Range Mountains of the U.S. state of California. As of the 2020 census, the population was 64,209. The c ...

57.59%

#

San Luis Obispo County, California

San Luis Obispo County (), officially the County of San Luis Obispo, is a county on the Central Coast of California. As of the 2020 census, the population was 282,424. The county seat is San Luis Obispo.

Junípero Serra founded the Missi ...

56.37%

Adaptation

The election parade for William McKinley is seen on

''The Little House'' film in 1952.

See also

*

American election campaigns in the 19th century

In the 19th century, a number of new methods for conducting American election campaigns developed in the United States. For the most part the techniques were original, not copied from Europe or anywhere else. The campaigns were also changed by a g ...

*

History of the United States (1865–1918)

*

First inauguration of William McKinley

The first inauguration of William McKinley as the 25th president of the United States took place on Thursday, March 4, 1897, in front of the Old Senate Chamber at the United States Capitol, Washington, D.C. This was the 28th inauguration and m ...

*

Political interpretations of ''The Wonderful Wizard of Oz''

*

Third Party System

In the terminology of historians and political scientists, the Third Party System was a period in the history of political parties in the United States from the 1850s until the 1890s, which featured profound developments in issues of American n ...

*

1896 United States House of Representatives elections

The 1896 United States House of Representatives elections, coincided with the election of President William McKinley. The Republican Party maintained its large majority in the House but lost 48 seats, mostly to the Democratic and Populist parties ...

*

1896 and 1897 United States Senate elections

Events

January–March

* January 2 – The Jameson Raid comes to an end, as Jameson surrenders to the Boers.

* January 4 – Utah is admitted as the 45th U.S. state.

* January 5 – An Austrian newspaper reports that ...

References

Further reading

*

*

*

* Burnham, Walter Dean. "The system of 1896: An analysis" in Paul Kleppner, W.D. Burnham, Ronald P. Formisano, Samuel P. Hays, Richard Jensen, and Walter G. Shade. ''The Eevolution of American electoral systems'' (Greenwood, 1981) pp. 147-202.

*

* Diamond, William, "Urban and Rural Voting in 1896," ''American Historical Review,'' (1941) 46#2 pp. 281–30

in JSTOR*

Durden, Robert Franklin

Robert Franklin Durden (May 10, 1925 - March 4, 2016) was an American historian and author at who worked at Duke University. He wrote books about Duke's history, journalist James S. Pike, and historian Carter G. Woodson.

He was born in Graymont, ...

"The 'Cow-bird' Grounded: The Populist Nomination of Bryan and Tom Watson in 1896," ''Mississippi Valley Historical Review'' (1963) 50#3 pp. 397–42

in JSTOR* Edwards, Rebecca. "The election of 1896." ''OAH Magazine of History'' 13.4 (1999): 28–30

online brief overview* Fahey, James J. "Building Populist Discourse: An Analysis of Populist Communication in American Presidential Elections, 1896–2016." ''Social Science Quarterly'' 102.4 (2021): 1268–1288

online*

*

*

*

* Harpine, William D. ''From the Front Porch to the Front Page: McKinley and Bryan in the 1896 Presidential Campaign'' (2006) focus on the speeches and rhetoric

* Horner, William T. ''Ohio’s Kingmaker: Mark Hanna, Man and Myth'' (Ohio University Press, 2010.)

*

*

*

*

Kazin, Michael. ''A Godly Hero: The Life of William Jennings Bryan'' (2006).

*

*

*

*

* detailed narrative of the entire campaign by

Karl Rove

Karl Christian Rove (born December 25, 1950) is an American Republican political consultant, policy advisor, and lobbyist. He was Senior Advisor and Deputy Chief of Staff during the George W. Bush administration until his resignation on Augu ...

a prominent 21st-century Republican campaign advisor.

* Stonecash, Jeffrey M.; Silina, Everita. "The 1896 Realignment," ''American Politics Research,'' (Jan 2005) 33#1 pp. 3–32

* Wanat, John and Karen Burke, "Estimating the Degree of Mobilization and Conversion in the 1890s: An Inquiry into the Nature of Electoral Change," ''American Political Science Review,'' (1982) 76#2 pp. 360–7

in JSTOR

* Wells, Wyatt. ''Rhetoric of the standards: The debate over gold and silver in the 1890s," ''Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era'' (2015). 14#1 pp. 49–68.

*

* Williams, R. Hal. (2010) ''Realigning America: McKinley, Bryan, and the Remarkable Election of 1896'' (University Press of Kansas) 250 pp

Primary sources

* Bryan, William Jennings. ''First Battle'' (1897), speeches from 1896 campaign

online

*

** This is the handbook of the Gold Democrats and strongly opposed Bryan.

*

*

* Porter, Kirk H. and Donald Bruce Johnson, eds. ''National party platforms, 1840-1964'' (1965

online 1840-1956* Whicher, George F., ed. ''William Jennings Bryan and the Campaign of 1896'' (1953), primary and secondary sources

online

External links

from the Library of Congress

McKinley & Hobart campaign handkerchief in the Staten Island Historical Society Online Collections DatabaseElection of 1896 in Counting the Votes

{{1896 United States elections

People's Party (United States)

Presidency of William McKinley

William McKinley

William Jennings Bryan

November 1896 events

1896 in American politics

The pro-gold Democrats reacted to Bryan's nomination with a mixture of anger, desperation, and confusion. A number of pro-gold Bourbon Democrats urged a "bolt" and the formation of a third party. In response, a hastily arranged assembly on July 24 organized the National Democratic Party. A follow-up meeting in August scheduled a nominating convention for September in

The pro-gold Democrats reacted to Bryan's nomination with a mixture of anger, desperation, and confusion. A number of pro-gold Bourbon Democrats urged a "bolt" and the formation of a third party. In response, a hastily arranged assembly on July 24 organized the National Democratic Party. A follow-up meeting in August scheduled a nominating convention for September in  Despite their advanced ages, Palmer and Buckner embarked on a busy speaking tour, including visits to most major cities in the East. This won them considerable respect from the party faithful, although some found it hard to take the geriatric campaigning seriously. "You would laugh yourself sick could you see old Palmer," wrote lawyer

Despite their advanced ages, Palmer and Buckner embarked on a busy speaking tour, including visits to most major cities in the East. This won them considerable respect from the party faithful, although some found it hard to take the geriatric campaigning seriously. "You would laugh yourself sick could you see old Palmer," wrote lawyer  Increasingly, the Republicans personalized their attacks on Bryan as a dangerous religious fanatic. The counter-crusading rhetoric focused on Bryan as a reckless revolutionary whose policies would destroy the economic system. Illinois Governor