Treaty of Paris (1763) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Treaty of Paris, also known as the Treaty of 1763, was signed on 10 February 1763 by the kingdoms of

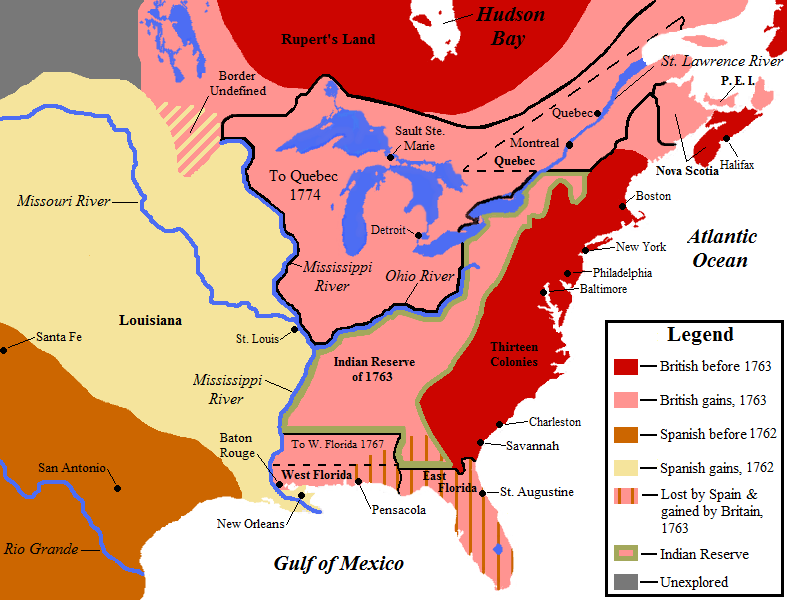

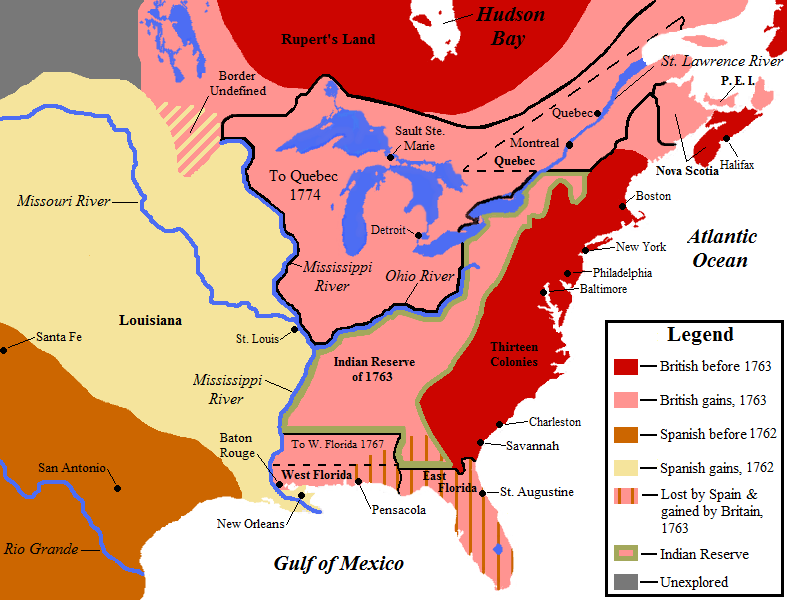

In the treaty, most of the territories were restored to their original owners, but Britain was allowed to keep considerable gains. France and Spain restored all their conquests to Britain and Portugal. Britain restored Manila and Havana to Spain, and Guadeloupe, Martinique, Saint Lucia, Gorée, and the Indian factories to France. In return, France recognized the sovereignty of Britain over

In the treaty, most of the territories were restored to their original owners, but Britain was allowed to keep considerable gains. France and Spain restored all their conquests to Britain and Portugal. Britain restored Manila and Havana to Spain, and Guadeloupe, Martinique, Saint Lucia, Gorée, and the Indian factories to France. In return, France recognized the sovereignty of Britain over  Treaty of Paris (1763) at

Treaty of Paris (1763) at  Treaty of Paris (1763) at

Treaty of Paris (1763) at

The article provided for unrestrained emigration for 18 months from Canada. However, passage on British ships was expensive. A total of 1,600 people left New France by that clause, but only 270 of them were French Canadians. Some claim that there was a deliberate British policy to limit emigration to avoid strengthening other French colonies.

Article IV of the treaty allowed Roman Catholicism to be practiced in Canada.Conklin p 34

The article provided for unrestrained emigration for 18 months from Canada. However, passage on British ships was expensive. A total of 1,600 people left New France by that clause, but only 270 of them were French Canadians. Some claim that there was a deliberate British policy to limit emigration to avoid strengthening other French colonies.

Article IV of the treaty allowed Roman Catholicism to be practiced in Canada.Conklin p 34

Treaty of Paris Profile and Videos

– Chickasaw.TV

The Treaty of Paris and its Consequences

Entry on the Treaty of Paris from ''The Canadian Encyclopedia''

Treaty of Paris

at the Avalon Project of the Yale Law School {{DEFAULTSORT:Treaty Of Paris (1763) Treaties of the Seven Years' War 1763 treaties Paris (1763) Paris (1763) 1763 in France 1763 in Great Britain 1763 in Spain 18th century in Paris France–Great Britain relations French and Indian War History of Saint Pierre and Miquelon Legal history of Canada Military history of Quebec New France Pre-Confederation Canada 1763 in the British Empire 1763 in the French colonial empire 1763 in Canada 1763 in New France 1763 in North America History of Quebec Pre-Confederation Quebec

Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It ...

, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

and Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

, with Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of th ...

in agreement, after Great Britain and Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an e ...

's victory over France and Spain during the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754 ...

.

The signing of the treaty formally ended conflict between France and Great Britain over control of North America (the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754 ...

, known as the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the st ...

in the United States), and marked the beginning of an era of British dominance outside Europe. Great Britain and France each returned much of the territory that they had captured during the war, but Great Britain gained much of France's possessions in North America. Additionally, Great Britain agreed to protect Roman Catholicism in the New World. The treaty did not involve Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an e ...

and Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

as they signed a separate agreement, the Treaty of Hubertusburg, five days later.

Exchange of territories

During the war, Great Britain had conquered the French colonies ofCanada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by to ...

, Guadeloupe

Guadeloupe (; ; gcf, label= Antillean Creole, Gwadloup, ) is an archipelago and overseas department and region of France in the Caribbean. It consists of six inhabited islands— Basse-Terre, Grande-Terre, Marie-Galante, La Désirade, and ...

, Saint Lucia

Saint Lucia ( acf, Sent Lisi, french: Sainte-Lucie) is an island country of the West Indies in the eastern Caribbean. The island was previously called Iouanalao and later Hewanorra, names given by the native Arawaks and Caribs, two Ameri ...

, Martinique

Martinique ( , ; gcf, label= Martinican Creole, Matinik or ; Kalinago: or ) is an island and an overseas department/region and single territorial collectivity of France. An integral part of the French Republic, Martinique is located in ...

, Dominica

Dominica ( or ; Kalinago: ; french: Dominique; Dominican Creole French: ), officially the Commonwealth of Dominica, is an island country in the Caribbean. The capital, Roseau, is located on the western side of the island. It is geographical ...

, Grenada

Grenada ( ; Grenadian Creole French: ) is an island country in the West Indies in the Caribbean Sea at the southern end of the Grenadines island chain. Grenada consists of the island of Grenada itself, two smaller islands, Carriacou and Pet ...

, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

Saint Vincent and the Grenadines () is an island country in the Caribbean. It is located in the southeast Windward Islands of the Lesser Antilles, which lie in the West Indies at the southern end of the eastern border of the Caribbean Se ...

, and Tobago

Tobago () is an island and ward within the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago. It is located northeast of the larger island of Trinidad and about off the northeastern coast of Venezuela. It also lies to the southeast of Grenada. The offic ...

, the French "factoreries" (trading posts) in India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

, the slave-trading station at Gorée, the Sénégal River

,french: Fleuve Sénégal)

, name_etymology =

, image = Senegal River Saint Louis.jpg

, image_size =

, image_caption = Fishermen on the bank of the Senegal River estuary at the outskirts of Saint-Louis, Senegal ...

and its settlements, and the Spanish colonies of Manila

Manila ( , ; fil, Maynila, ), officially the City of Manila ( fil, Lungsod ng Maynila, ), is the capital of the Philippines, and its second-most populous city. It is highly urbanized and, as of 2019, was the world's most densely populated ...

(in the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

) and Havana

Havana (; Spanish: ''La Habana'' ) is the capital and largest city of Cuba. The heart of the La Habana Province, Havana is the country's main port and commercial center.

(in Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribb ...

). France had captured Minorca and British trading posts in Sumatra

Sumatra is one of the Sunda Islands of western Indonesia. It is the largest island that is fully within Indonesian territory, as well as the sixth-largest island in the world at 473,481 km2 (182,812 mi.2), not including adjacent i ...

, while Spain had captured the border fortress of Almeida in Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of th ...

, and Colonia del Sacramento in South America.

Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by to ...

, Dominica, Grenada, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, and Tobago."His Most Christian Majesty cedes and guaranties to his said Britannick Majesty, in full right, Canada, with all its dependencies, as well as the island of Cape Breton, and all the other islands and coasts in the gulph and river of St. Lawrence, and in general, every thing that depends on the said countries, lands, islands, and coasts, with the sovereignty, property, possession, and all rights acquired by treaty, or otherwise, which the Most Christian King and the Crown of France have had till now over the said countries, lands, islands, places, coasts, and their inhabitants" – Article IV of the Wikisource

Wikisource is an online digital library of free-content textual sources on a wiki, operated by the Wikimedia Foundation. Wikisource is the name of the project as a whole and the name for each instance of that project (each instance usually re ...

France also ceded the eastern half of French Louisiana to Britain; that is, the area from the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the List of longest rivers of the United States (by main stem), second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest Drainage system (geomorphology), drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson B ...

to the Appalachian Mountains

The Appalachian Mountains, often called the Appalachians, (french: Appalaches), are a system of mountains in eastern to northeastern North America. The Appalachians first formed roughly 480 million years ago during the Ordovician Period. The ...

."... it is agreed, that ... the confines between the dominions of his Britannick Majesty and those of his Most Christian Majesty, in that part of the world, shall be fixed irrevocably by a line drawn along the middle of the River Mississippi, from its source to the river Iberville, and from hence, by a line drawn along the middle of this river, and the lakes Maurepas and Pontchartrain to the sea; and for this purpose, the Most Christian King cedes in full right, and guaranties to his Britannick Majesty the river and port of Mobile, and every thing which he possesses, or ought to possess, on the left side of the river Mississippi, except the town of New Orleans and the island in which it is situated, which shall remain to France, ..." – Article VII of the Wikisource

Wikisource is an online digital library of free-content textual sources on a wiki, operated by the Wikimedia Foundation. Wikisource is the name of the project as a whole and the name for each instance of that project (each instance usually re ...

France had already secretly given Louisiana to Spain in the Treaty of Fontainebleau (1762), but Spain did not take possession until 1769. Spain ceded East Florida to Britain. In addition, France regained its factories in India but recognized British clients as the rulers of key Indian native states and pledged not to send troops to Bengal

Bengal ( ; bn, বাংলা/বঙ্গ, translit=Bānglā/Bôngô, ) is a geopolitical, cultural and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the eastern part of the Indian subcontinent at the apex of the Bay of Bengal, predom ...

. Britain agreed to demolish its fortifications in British Honduras

British Honduras was a British Crown colony on the east coast of Central America, south of Mexico, from 1783 to 1964, then a self-governing colony, renamed Belize in June 1973,

(now Belize

Belize (; bzj, Bileez) is a Caribbean and Central American country on the northeastern coast of Central America. It is bordered by Mexico to the north, the Caribbean Sea to the east, and Guatemala to the west and south. It also shares a wa ...

) but retained a logwood-cutting colony there. Britain confirmed the right of its new subjects to practise Catholicism.

France lost all of its territory in mainland North America except for the territory of Louisiana west of the Mississippi River. France retained fishing rights off Newfoundland and the two small islands of Saint Pierre and Miquelon

Saint Pierre and Miquelon (), officially the Territorial Collectivity of Saint-Pierre and Miquelon (french: link=no, Collectivité territoriale de Saint-Pierre et Miquelon ), is a self-governing territorial overseas collectivity of France in t ...

, where its fishermen could dry their catch. In turn, France gained the return of its sugar colony, Guadeloupe, which it considered more valuable than Canada. Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778) was a French Enlightenment writer, historian, and philosopher. Known by his '' nom de plume'' M. de Voltaire (; also ; ), he was famous for his wit, and his criticism of Christianity—e ...

had notoriously dismissed Acadia as (a few acres of snow).

Louisiana question

The Treaty of Paris is frequently noted as France giving Louisiana to Spain. However, the agreement to transfer had occurred with the Treaty of Fontainebleau (1762), but it was not publicly announced until 1764. The Treaty of Paris gave Britain the east side of the Mississippi (includingBaton Rouge, Louisiana

Baton Rouge ( ; ) is a city in and the List of capitals in the United States, capital of the U.S. state of Louisiana. Located the eastern bank of the Mississippi River, it is the county seat, parish seat of East Baton Rouge Parish, Louisiana, E ...

, which was to be part of the British territory of West Florida). New Orleans, on the east side, remained in French hands (albeit temporarily). The Mississippi River corridor in what is now Louisiana was later reunited following the Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (french: Vente de la Louisiane, translation=Sale of Louisiana) was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or ap ...

in 1803 and the Adams–Onís Treaty

The Adams–Onís Treaty () of 1819, also known as the Transcontinental Treaty, the Florida Purchase Treaty, or the Florida Treaty,Weeks, p.168. was a treaty between the United States and Spain in 1819 that ceded Florida to the U.S. and define ...

in 1819.

The 1763 treaty states in Article VII:

Canada question

British perspective

The war was fought all over the world, but the British began the war over French possessions inNorth America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and th ...

. After a long debate of the relative merits of Guadeloupe, which produced £6 million a year in sugar, and Canada, which was expensive to keep, Great Britain decided to keep Canada for strategic reasons and to return Guadeloupe to France. The war had weakened France, but it was still a European power. British Prime Minister Lord Bute wanted a peace that would not push France towards a second war.

Although the Protestant British worried about having so many Roman Catholic subjects, Great Britain did not want to antagonize France by expulsion or forced conversion or for French settlers to leave Canada to strengthen other French settlements in North America.

French perspective

Unlike Lord Bute, the French Foreign Minister, the Duke of Choiseul, expected a return to war. However, France needed peace to rebuild. France preferred to keep its Caribbean possessions with their profitable sugar trade, rather than the vast Canadian lands, which had been a financial burden on France. French diplomats believed that without France to keep the Americans in check, the colonists might attempt to revolt. In Canada, France wanted open emigration for those, such as the nobility, who would not swear allegiance to the British Crown. Finally, France required protection for Roman Catholics in North America. Article IV stated:Dunkirk question

During the negotiations that led to the treaty, a major issue of dispute between Britain and France had been over the status of the fortifications of the French coastal settlement ofDunkirk

Dunkirk (french: Dunkerque ; vls, label=French Flemish, Duunkerke; nl, Duinkerke(n) ; , ;) is a commune in the department of Nord in northern France.

. The British had long feared that it would be used as a staging post to launch a French invasion of Britain

The term Invasion of England may refer to the following planned or actual invasions of what is now modern England, successful or otherwise.

Pre-English Settlement of parts of Britain

* The 55 and 54 BC Caesar's invasions of Britain.

* The 43 A ...

. Under the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht, the British had forced France to concede extreme limits on those fortifications. The 1748 Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle had allowed more generous terms, and France constructed greater defences for the town.

The 1763 treaty had Britain force France to accept the 1713 conditions and to demolish the fortifications that had been constructed since then. That would be a continuing source of resentment to France, which would eventually have that provision overturned in the 1783 Treaty of Paris, which brought an end to the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

.

Reactions

When Lord Bute became the British prime minister in 1762, he pushed for a resolution to the war with France and Spain since he feared that Great Britain could not govern all of its newly acquired territories. In whatWinston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

would later term a policy of "appeasement", Bute returned some colonies to Spain and France in the negotiations.

Despite a desire for peace, many in the British Parliament opposed the return of any gains made during the war. Notable among the opposition was former Prime Minister William Pitt, the Elder, who warned that the terms of the treaty would lead to further conflicts once France and Spain had time to rebuild and later said, "The peace was insecure because it restored the enemy to her former greatness. The peace was inadequate, because the places gained were no equivalent for the places surrendered." The treaty passed by 319 votes to 65.

The Treaty of Paris took no consideration of Great Britain's battered continental ally, Frederick II of Prussia

Frederick II (german: Friedrich II.; 24 January 171217 August 1786) was King in Prussia from 1740 until 1772, and King of Prussia from 1772 until his death in 1786. His most significant accomplishments include his military successes in the S ...

, who was forced to negotiate peace terms separately in the Treaty of Hubertusburg. For decades after the signing of the Treaty of Paris, Frederick II decried it as a British betrayal.

Many Protestant American colonists were disappointed by the protection of Roman Catholicism in the Treaty of Paris.Monod p. 201 Criticism of the British colonial government as insufficiently anti-Catholic and fear of the protections for Catholicism expanding beyond Quebec was one of many reasons for the breakdown of American–British relations that led to the American Revolution.

Effects on French Canada

The article provided for unrestrained emigration for 18 months from Canada. However, passage on British ships was expensive. A total of 1,600 people left New France by that clause, but only 270 of them were French Canadians. Some claim that there was a deliberate British policy to limit emigration to avoid strengthening other French colonies.

Article IV of the treaty allowed Roman Catholicism to be practiced in Canada.Conklin p 34

The article provided for unrestrained emigration for 18 months from Canada. However, passage on British ships was expensive. A total of 1,600 people left New France by that clause, but only 270 of them were French Canadians. Some claim that there was a deliberate British policy to limit emigration to avoid strengthening other French colonies.

Article IV of the treaty allowed Roman Catholicism to be practiced in Canada.Conklin p 34 George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Br ...

agreed to allow Catholicism within the laws of Great Britain, which included various Test Acts to prevent governmental, judicial and bureaucratic appointments from going to Roman Catholics. They were believed to be agents of the Jacobite pretenders to the throne, who normally resided in France and were supported by its government. The Test Acts were somewhat relaxed in Quebec, but top positions such as governorships were still held by Anglicans.

Article IV has also been cited as the basis for Quebec often having its unique set of laws that are different from the rest of Canada. There was a general constitutional principle in the United Kingdom to allow colonies that were taken through conquest to continue their own laws.Conklin p 35 That was limited by royal prerogative

The royal prerogative is a body of customary authority, privilege and immunity, recognized in common law and, sometimes, in civil law jurisdictions possessing a monarchy, as belonging to the sovereign and which have become widely vested in th ...

, which allowed the monarch to change the accepted laws in a conquered colony later. However, the treaty eliminated that power because of a different constitutional principle, which considered terms of a treaty to be paramount. In practice, Roman Catholics were allowed become jurors in inferior courts in Quebec and to argue based on principles of French law.Calloway p 120 However, the judge was British, and his opinion on French law could be limited or hostile. If the case was appealed to a superior court, neither French law nor Roman Catholic jurors were allowed.

Many French residents of what are now the Maritime Provinces

The Maritimes, also called the Maritime provinces, is a region of Eastern Canada consisting of three provinces: New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island. The Maritimes had a population of 1,899,324 in 2021, which makes up 5.1% o ...

of Canada were deported during the Great Expulsion of the Acadians

The Acadians (french: Acadiens , ) are an ethnic group descended from the French who settled in the New France colony of Acadia during the 17th and 18th centuries. Most Acadians live in the region of Acadia, as it is the region where the de ...

(1755–1763). After the signing of the peace treaty guaranteed some rights to Roman Catholics, some Acadians returned to Canada. However, they were no longer welcome in the British colony of Nova Scotia. They were forced into New Brunswick, which became a bilingual province as a result of that relocation.

Much land that had been owned by France was now owned by Britain, and the French people of Quebec felt greatly betrayed at the French concession. The commander-in-chief of the British, Jeffrey Amherst noted, "Many of the Canadians consider their Colony to be of utmost consequence to France & cannot be convinced ... that their Country has been conceded to Great Britain."Calloway p 113

See also

* France in the Seven Years' War * Great Britain in the Seven Years' War *Royal Proclamation of 1763

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 was issued by King George III on 7 October 1763. It followed the Treaty of Paris (1763), which formally ended the Seven Years' War and transferred French territory in North America to Great Britain. The Procla ...

* List of treaties

This list of treaties contains known agreements, pacts, peaces, and major contracts between states, armies, governments, and tribal groups.

Before 1200 CE

1200–1299

1300–1399

1400–1499

1500–1599

1600–1699

1700–1799

...

References

Further reading

* * * * * *External links

Treaty of Paris Profile and Videos

– Chickasaw.TV

The Treaty of Paris and its Consequences

Entry on the Treaty of Paris from ''The Canadian Encyclopedia''

Treaty of Paris

at the Avalon Project of the Yale Law School {{DEFAULTSORT:Treaty Of Paris (1763) Treaties of the Seven Years' War 1763 treaties Paris (1763) Paris (1763) 1763 in France 1763 in Great Britain 1763 in Spain 18th century in Paris France–Great Britain relations French and Indian War History of Saint Pierre and Miquelon Legal history of Canada Military history of Quebec New France Pre-Confederation Canada 1763 in the British Empire 1763 in the French colonial empire 1763 in Canada 1763 in New France 1763 in North America History of Quebec Pre-Confederation Quebec